SUMMARY

The transmembrane domain of the Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) from Escherichia coli is an excellent model for structural and folding studies of β-barrel membrane proteins. However, full-length OmpA resists crystallographic efforts and the link between its function and tertiary structure remains controversial. Here we use site directed mutagenesis and mass spectrometry of different constructs of OmpA, released in the gas phase from detergent micelles, to define the minimal region encompassing the C-terminal dimer interface. Combining knowledge of the location of the dimeric interface with molecular modeling and ion mobility data allows us to propose a low-resolution model for the full-length OmpA dimer. Our model of the dimer is in remarkable agreement with experimental ion mobility data, with none of the unfolding or collapse observed for full-length monomeric OmpA, implying that dimer formation stabilises the overall structure and prevents collapse of the flexible linker that connects the two domains.

INTRODUCTION

Integral outer membrane proteins (OMPs) of Gram-negative bacteria are responsible for many critical functions such as interacting with host tissues, translocating proteins or solutes, transducing signals and maintaining the structural integrity of the cell (Kim et al., 2012; Krishnan and Prasadarao, 2012). OmpA, one of the most abundant proteins in Escherichia coli, is found at about 100 000 copies per cell. This extensively studied protein contains 325 amino acid residues and consists of two distinct domains. The N-terminal domain (TM-OmpA) comprises 169 amino acid residues and forms a transmembrane eight-stranded β-barrel as revealed by both X-ray crystallography (Pautsch and Schulz, 1998) and NMR spectroscopy (Arora et al., 2001). The highly conserved C-terminal periplasmic domain (CTD-OmpA, 156 residues) was proposed to interact with the peptidoglycan layer in the periplasm (De Mot and Vanderleyden, 1994; Sonntag et al., 1978). Despite repeated efforts, it has resisted crystallization for the past 30 years. However, the structures of several homologs of CTD-OmpA have been solved. They include the protein RmpM from Neisseria meningitides (~40% sequence identity with CTD-OmpA from E.coli) (Grizot and Buchanan, 2004) and the CTD-OmpA from Acinetobacter baumannii (~20% sequence identity) (Park et al., 2012). In addition, the structure of CTD-OmpA from Salmonella enterica (~94% sequence identity) has been deposited recently in the PDB (accession code: 4ERH). A first model of the full length (FL)-OmpA structure was generated by manually fusing the RmpM protein to the N-terminal β-barrel from Pasteurella multocida (Khalid et al., 2008). The recent structure of the A. baumannii CTD-OmpA further suggested a molecular model for the interaction of this domain with the periplasmic peptidoglycan layer (Park et al., 2012).

OmpA has also been proposed to function as an ion-channel or porin in the outer membrane of E. coli (Arora et al., 2000; Saint et al., 1993; Sugawara and Nikaido, 1992, 1994) as well as in other species (Sugawara and Nikaido, 2012). This activity was initially controversial because small and large conductance levels were observed in different studies. The smaller conductances were 50 times lower than those of other well characterized porins such as OmpF. The larger conductances were only seen with FL-OmpA, whereas TM-OmpA only exhibited the relatively noisy small conductance behavior. This behavior is consistent with the crystal structure, which revealed the presence of several discontinuous water cavities rather than a continuous water-filled pore (Pautsch and Schulz, 1998). However, as suggested by MD simulations (Bond et al., 2002), mutagenesis of several charged pore gating residues and corresponding thermodynamic stability and NMR relaxation experiments revealed a re-arrangement of the hydrogen bonding network within the barrel that could generate fluctuating small conductance levels of the channel (Hong et al., 2006).

While most porins form trimers of 16 or 18-stranded β-barrels, the 12-stranded β-barrel phospholipase OmpLA from E. coli forms a dimer (Snijder et al., 2001; Snijder et al., 1999). OmpA is often considered to be monomeric, although FL-OmpA bands corresponding to dimers are often seen with refolded proteins (Rodionova et al., 1995) or on blue native-SDS-polycrylamide gels (Stenberg et al., 2005). Recently, the presence of OmpA homodimers was confirmed by cross-linking in vivo (Zheng et al., 2011). These studies localized the dimeric interface within the periplasmic CTD of OmpA. The CTD-OmpA from S. enterica crystallised with two molecules in the asymmetric unit, but the functional or structural relevance of this result is still lacking. These several circumstantial indications that OmpA may indeed exist and function as a dimer, prompted us to investigate the oligomeric state of OmpA using mass spectrometry (MS).

With the advent of improved instrumentation and methodologies, non-denaturing MS has been applied increasingly to the study of membrane protein complexes (Marcoux and Robinson, 2013). Pioneering efforts in this field led to uncovering the subunit stoichiometry and the identification of interactions between different membrane proteins (Barrera et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). The binding of lipids to membrane proteins has also been studied by MS (Barrera et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2011). When MS is coupled with measurements of ion mobility (IM), IM-MS can provide topological information of gas phase ions in the form of an orientationally averaged collision cross-section (CCS) (Ruotolo et al., 2005). This experimental setup enables the gas-phase separation of ions not only according to their mass-to-charge ratio, but also according to their shape or conformation. The CCS values (in Å2) depend on the size and shape of the proteins in the gas phase and can be used to examine conformational changes and distinguish between different structural models of proteins (Ruotolo et al., 2008; Ruotolo et al., 2005). They may also be used as restraints to model previously unknown structures (Baldwin et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2012b; Politis et al., 2013). Using these methods, we previously demonstrated that the quaternary structures of two tetrameric membrane proteins could be preserved in the gas-phase (Wang et al., 2010). We also applied IM-MS to examine the conformational dynamics of the F1Fo ATPase from Thermus thermophilus (Zhou et al., 2014) and the murine ABC transporter P-glycoprotein (Marcoux et al., 2013).

In the present study we employed MS to examine the quaternary structure of OmpA and found coexisting populations of monomers and dimers in detergent micelles. To define the dimer interface, the oligomeric states of several deletion constructs of OmpA were determined by MS and IM-MS was used to obtain topological information on these constructs. The crystal and NMR structures of TM-OmpA together with a homology model of CTD-OmpA based on the crystal structure from S. enterica were combined with MS and chemical cross-linking (Zheng et al., 2011)-derived restraints to build a new model of full-length OmpA from E. coli, based on experimental data.

RESULTS

A hybrid experimental and modeling strategy

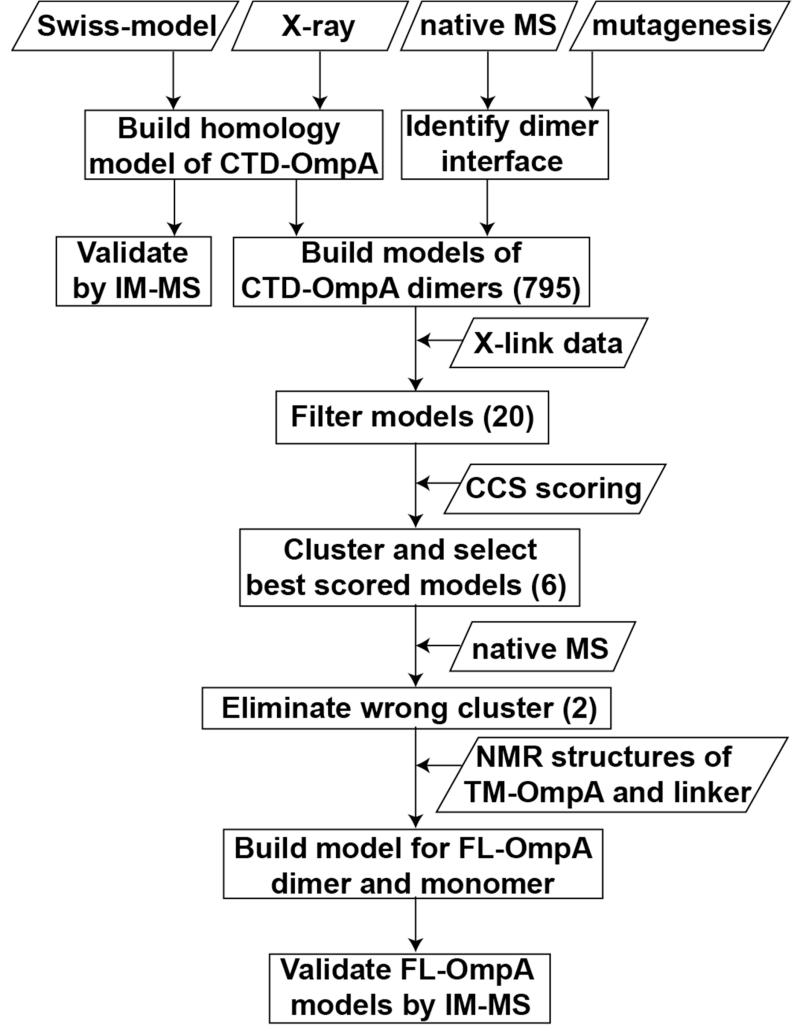

The workflow describing our hybrid experimental and modeling strategy to determine low-resolution structural models of full-length OmpA is depicted in Figure 1 and Figure S1. We prepared several deletion and point mutations of OmpA (Figure 2A) and employed native MS to localise the dimer interface to the CTD of OmpA. We next generated models for monomeric and dimeric CTD-OmpA, screened them with previously determined chemical cross-linking restraints, and scored them with experimental CCS data from IM-MS experiments. The best model of the CTD-OmpA dimer was then combined with the NMR structure of the N-terminal β-barrel TM domain and the resulting FL-OmpA monomer and dimer models were validated by IM-MS.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of hybrid experimental and modeling approaches to generate models of full-length OmpA.

A model of CTD-OmpA was generated with SwissModel and 795 models of the corresponding dimer were generated with SymmDock. Each model was filtered based on cross-linking data and scored with IM-MS data. The best representative was selected to model FL-OmpA by building chimeras based on the NMR structure of TM-OmpA (1G90) and of the homologous linker from 2K0L. The models of FL-OmpA were finally validated by IM-MS see also Figure S1.

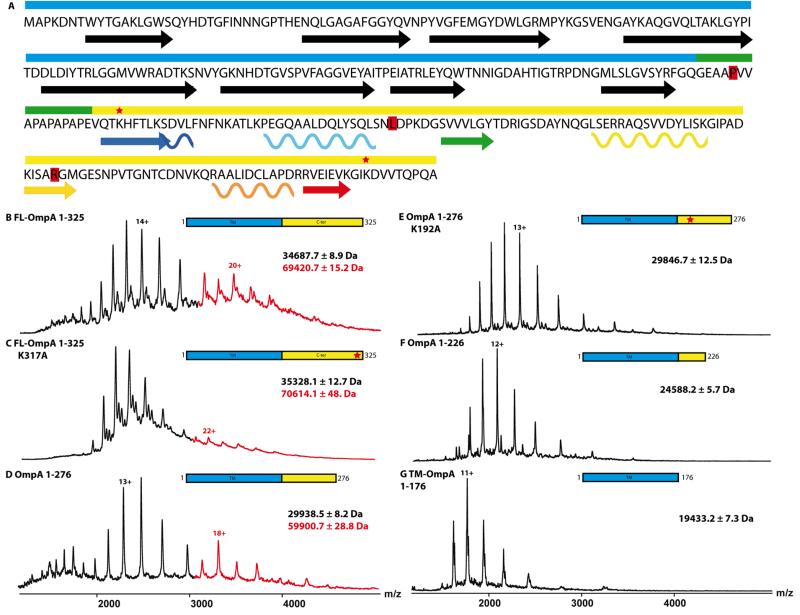

Figure 2. The C-terminal domain of OmpA is responsible for partial dimerization.

(A) FL-OmpA is composed of a N-terminal transmembrane β-barrel (cyan) and a periplasmic C-terminal domain (yellow) separated by a proline-rich linker (green). The 8 strands of the barrel are represented by black arrows and the secondary structure helices and strands of the CTD are color-coded as seen in Figure 3. The residues highlighted in red represent the locations of the STOP mutations inserted at P177, L227 and R277. (B-G) Mass spectra obtained from native solution conditions for the different transmembrane constructs. The peaks corresponding to the dimer are highlighted in red. All constructs were sprayed at concentration between 10 μM (FL-OmpA) and 30 μM (TM-OmpA) see also Figure S2 and Table S1. The red stars indicate lysines 192 and 317 that were changed to alanines in some constructs.

Residues 188-276 are responsible for partial OmpA dimerization

The quaternary structures of FL-OmpA and TM-OmpA were analysed in n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (DDM) micelles by native MS, i.e, using carefully controlled MS conditions designed to disrupt micelles but to retain subunit interactions (Barrera et al., 2009; Marcoux and Robinson, 2013). While TM-OmpA showed several charge states corresponding to monomers (Fig. 2G), FL-OmpA displayed a second set of peaks (shown in red in Figure 2B), that indicate the presence of dimers. This dimer can be unequivocally assigned and differentiated from the monomer using the additional separation dimension provided by ion mobility (Figure S2).

In order to define more precisely the dimer interface, we inserted stop codons after residues 276 and 226 (Figure 2A and Table S1). The oligomeric state of the resulting truncated proteins were assessed using non-denaturing MS. OmpA 1-276 was found to form a population of dimers, whereas OmpA 1-226 was present only as a monomer (Figure 2D-F). These results were confirmed in solution by chemical cross-linking. Equal amounts of the four constructs were incubated with ethylene glycol-disuccinimidylsuccinate (EGS) and loaded on a SDS-PAGE gel. The cross-linked FL-OmpA and construct OmpA(1-276) were observed as monomer and dimer, whereas constructs OmpA(1-176) and OmpA(1-226) show only monomeric species (Figure S2D).

Lysines 192 and 317 were shown to be cross-linked in vivo (Zheng et al., 2011), which prompted us to mutate these residues into alanines and assess the oligomeric state(s) of the resulting constructs using non-denaturing MS. The variant K317A retained the ability to form dimers, consistent with the results obtained for OmpA(1-276) (Figure 2C). However, the formation of dimers was abrogated in the K192A mutation and monomers were generated almost exclusively (Figure 2E).

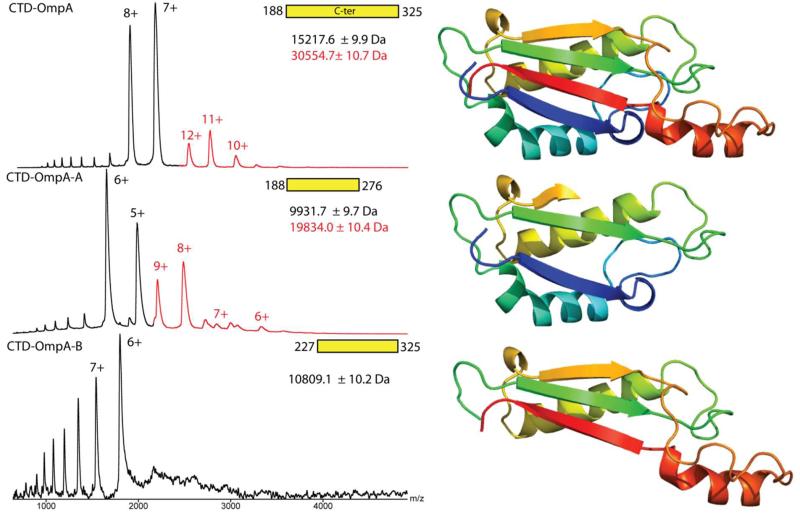

We next asked whether the C-terminal domains alone could form dimers. Therefore, we prepared and analysed three constructs of the soluble C-terminal domain: CTD-OmpA (residues 188-325), CTD-OmpA-A (residues 188-276) and CTD-OmpA-B (residues 227-325). The longest construct CTD-OmpA, encompassing the entire C-terminal region, was present as both monomers and dimers (Figure 3) over a concentration range that spans an order of magnitude (6.9 to 69 μM) (Figure S3). CTD-OmpA-A was also able to form dimers, as was the construct OmpA(1-276). However, CTD-OmpA-B was only present as a monomer, confirming that the minimal amino acid sequence 188-276 is required for dimer formation.

Figure 3. Residues 188-276 of the CTD are sufficient to form a dimer interface.

Spectra obtained under native conditions for the soluble C-terminal constructs of OmpA after cleavage of the 27 N-terminal residues (MBP+6-His tag) by the TEV protease. The corresponding structural models (based on PDB file 4ERH) are represented on the right. CTD-OmpA and CTD-OmpA-A but not CTD-OmpA-B were able to form a population of dimers (red) see also Figure S3.

Modeling of the CTD-OmpA Dimer

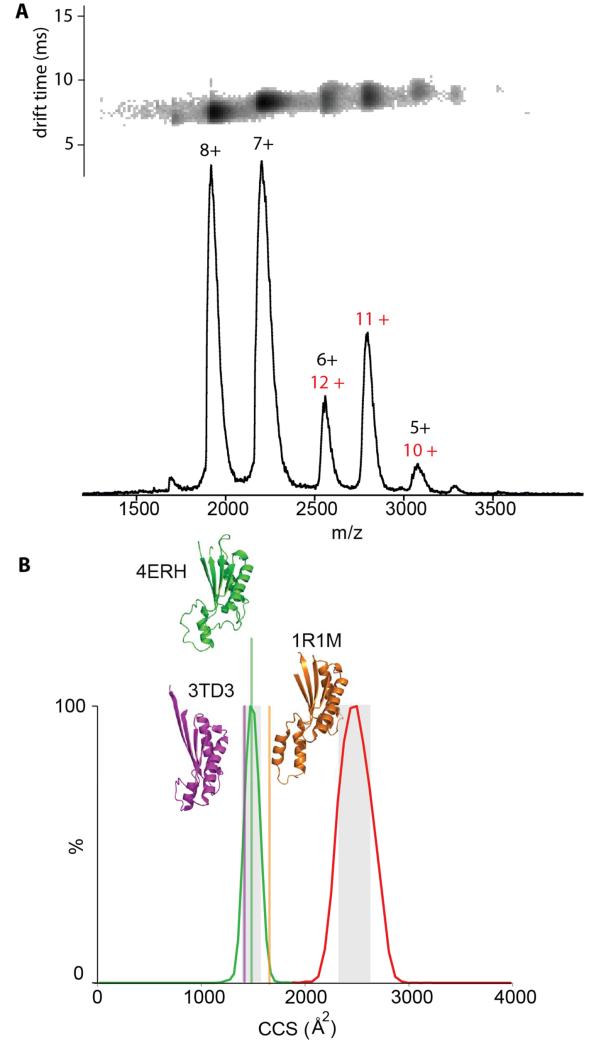

Having established the residues responsible for the dimerization of OmpA we set about building a model for FL-OmpA by combining information from three types of experiments, namely native MS from detergent micelles, IM-MS, and chemical cross-linking, the latter published elsewhere (Zheng et al., 2011). The crystal structure from S. enterica (PDB code 4ERH) was used as a template to generate a model for the monomeric C-terminal domain from E. coli (94% sequence identity, Figure S4) using the SWISS-MODEL Repository (Kiefer et al., 2009; Kopp and Schwede, 2004). The drift time measured for monomeric CTD-OmpA (Figure 4) gave rise to a collisional cross-section (CCS) of 1505 ± 25 Å2, in good agreement with the CCS of 1488 Å2 calculated for our model, validating our model of the monomeric CTD-OmpA. Interestingly, the CCS values calculated for the two other homologues of CTD-OmpA from A. baumannii and N. meningitidis, which had lower sequence identities (Figure S4) were 1420 Å2 and 1659 Å2, respectively, and agreed less well with our experimental data, showing IM-MS potential to differentiate even structurally similar homologues.

Figure 4. Evaluation of monomer and dimer models of CTD-OmpA by ion-mobility MS.

(A) Native mass spectrum of CTD-OmpA showing both monomer (charge states 8+ to 5+ black) and dimer (charge states 12+ to 10+ red). The inset shows the drift time obtained for each charge state. (B) Arrival time distributions converted to CCS for the charge states 7+ of the monomer (green) and 11+ of the dimer (red). Vertical lines show the CCSs calculated for our model of CTD-OmpA (green based on PDB file 4ERH from S. enterica) and from the PDB files 3TD3 (magenta from A. baumannii) and 1R1M (orange RmpM from N. meningitidis). The grey shaded area shows the ± 6% experimental error see also Figure S4.

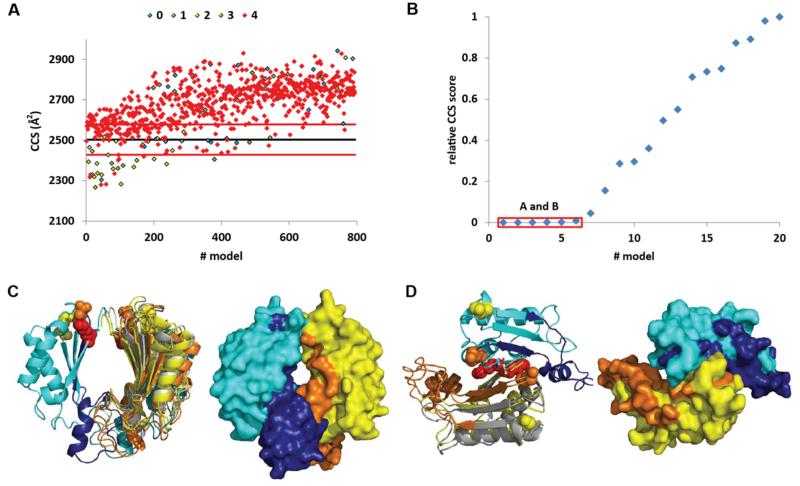

We next used the SymmDock molecular docking tool (Schneidman-Duhovny et al., 2005a, b) to generate symmetrical dimers of CTD-OmpA. The symmetrical restraint of the algorithm accounts for the relatively low number of models generated (795). However, as shown in Figure S1, the sampling was enough to generate a variety of dimeric interfaces that were assessed individually with experimental data. Two types of restraints were then used to screen the models generated: residue-specific distance restraints from previously published cross-linking experiments (Zheng et al., 2011) and the CCS of the C-terminal dimer from the IM-MS data.

Of these 795 models only 20 satisfied the four cross-linking restraints (Figure S5A and Table S2). Six of these models showed a CCS score <1% of the highest score (Figure 5A-B). These six best scored models can be classified into two groups with different spatial arrangements of the monomers. In one arrangement that was seen in four of the models, the dimeric interface was formed by the 50 last residues of the CTD (highlighted dark blue and orange in Figure 5C). In the second arrangement that was seen in two of the models, the orientation of the two monomers is similar as in the RmpM dimer and the crystal structure from S. enterica CTD-OmpA except that the two monomers are separated by approximately 25 Å. The four models in first arrangement could be rejected because the native MS and cross-linking experiments showed that the 50 most C-terminal residues were not necessary for dimerization (Figures 2 and 3). The two models in the second arrangement do not involve the 50 last residues, which is consistent with the native MS and cross-linking data (Figure 5 and S5). Interestingly residue K192, which has been shown to be important for the formation of dimers, is located in the dimer interface in these two models and residue K317, which has no effect on dimerization, is positioned far from the modelled interface (Figure S5C).

Figure 5. Scoring the SymmDock models of the CTD dimer.

(A) Plot of the CCS calculated for each dimer model. The cross-link scores are color coded (blue, green, yellow, orange and red diamonds corresponding to 0,1,2,3 and 4 penalties, respectively). The black line represents the experimental value obtained for the dimer of CTD-OmpA and the red lines show the ± 3% experimental error. (B) Plot of the CCS score obtained for the 20 models with no cross-link penalty. The red box shows the models with a score <1% of the highest score. (C) and (D) represent the two clusters observed amongst these lowest score models (solutions A and B, respectively). The regions colored dark blue and orange correspond to residues 277-325 which are not required for dimer formation see also Figure S5 and Table S2.

Ion-mobility MS reveals different conformations of TM-OmpA and FL-OmpA

Given the fact that the two N-terminal β-barrel domains of a FL-OmpA dimer must be embedded in the same membrane and that they most likely follow the symmetry of the CTDs, there are only limited possibilities for assembling the TM and flexible linker domains onto the CTD-OmpA dimer model (Figure 6A). The resulting model of the FL-OmpA dimer is consistent with the CCS of CTD-OmpA and results from crosslinking; we now need to validate the monomeric and dimeric FL models.

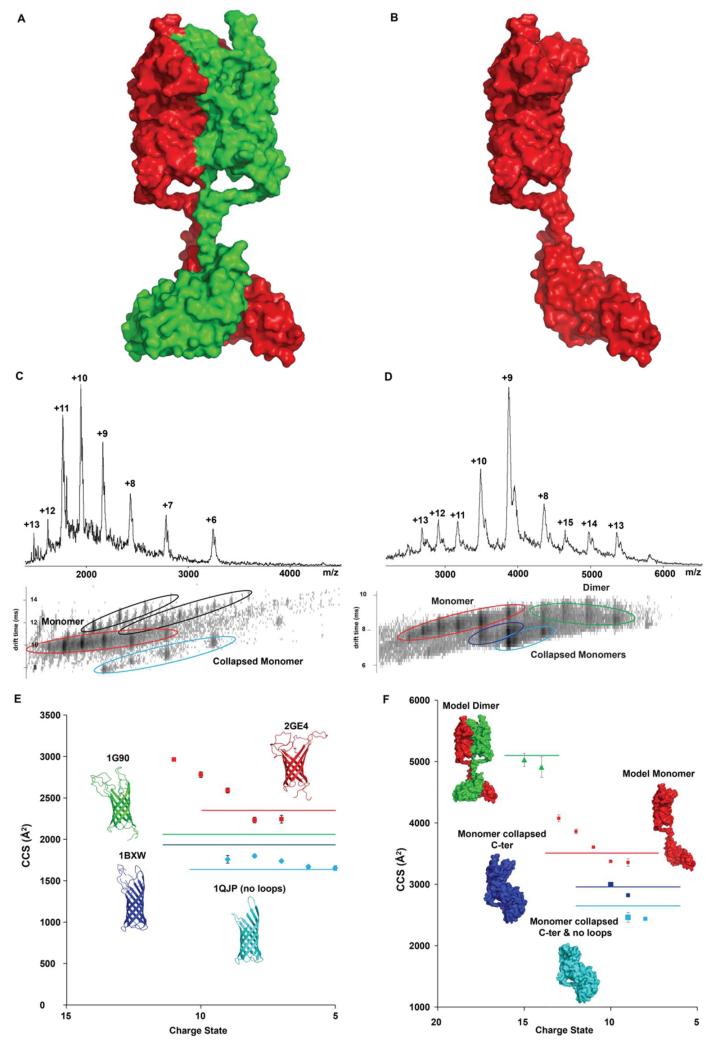

Figure 6. Experiment-supported models of FL-OmpA.

(A) dimer and (B) monomer models of FL-OmpA. (C) Mass spectrum and mobility contour plot for TM-OmpA showing, apart from detergent clusters (black), two different conformations: extended (red) and more compact (cyan). (D) Mass spectrum and mobility contour plot for FL-OmpA showing the presence of four different conformations: an extended monomer (red), two compact monomers (blue) and a dimer (green). (E) CCS values obtained for each charge state of the two TM conformers. The horizontal lines show the theoretical values calculated based on PDB files 2GE4 (red), 1G90 (green), 1BXW (dark blue) and 1QJP (cyan). Error bars are calculated from average CCS determined at 5 different drift voltages. (F) CCS values obtained for each charge state of the different FL conformers. The horizontal lines show the theoretical CCS values calculated for the models proposed here: monomer (red), dimer (green) and models for collapsed monomers with (blue) and without (cyan) the external loops. Error bars are calculated from average CCS determined at 5 different drift voltages.

To investigate the conformational state(s) of the TM and FL-OmpA and to validate the models generated above, we carried out IM-MS. The MS and IM contour plot of TM-OmpA shows different charge states from 6+ to 13+ (Figure 6C). Two charge state series could be discerned corresponding to a predominant extended (red) and a more compact (blue) conformation of monomeric TM-OmpA along with detergent clusters (black). CCSs were obtained for each one of these charge states and compared with theoretical values calculated using four different PDB files (Figure 6E). We assign the higher charge states to extended conformations, most likely due to Coulombic repulsion between charged residues as reported previously (Clemmer et al., 1995). The CCS measured for low charge states of the extended conformation were in good agreement with values calculated based on the NMR structures containing the same number of residues (PDB codes 2GE4 and 1G90). The CCS measured for the most compact conformer identified here corresponds to values calculated based on X-ray structures lacking the last 5 C-terminal residues of TM-OmpA (PDB code 1BXW) or lacking the flexible loops located on the extracellular side (PDB code 1QJP). This indicates that these residues are partially collapsed in the gas phase, in line with observations made for the small β-barrel membrane protein PagP (Borysik et al., 2013). We conclude therefore that the multiple conformations observed for TM-OmpA correspond to native-like and more extended conformations, together with structures in which the flexible loops or unstructured C-terminus are collapsed.

When similar experiments were carried out with FL-OmpA, the native mass spectra show dimeric and monomeric populations and IM-MS reveals compact dimers and both compact and extended monomers (Figure 6D). The overall similar CCS distribution patterns of FL- and TM-OmpA indicates that some compact conformers likely originate from a collapse of the loops and that the lower charge states of the extended conformer correspond to native-like populations of the monomer. The compact conformations could also arise from a collapse of the flexible linker bringing the C-terminal and TM domain in contact, as seen in IM-MS experiments of proteins containing intrinsically unstructured regions (Pagel et al., 2013) and in molecular dynamics simulations of monomeric FL-OmpA in a lipid bilayer (Khalid et al., 2008). When manually collapsing the C-terminal region of the FL-OmpA monomer onto the TM domain, and calculating a CCS for this model, we obtain a value that is in good agreement with the one determined experimentally (Figure 6F, blue line). Therefore the lowest CCS observed for the monomer most likely corresponds to a collapse of both the flexible linker and the external loops (Figure 6F, cyan line). The theoretical CCS measured for our model of FL-OmpA dimer is however in remarkably good agreement with our experimental values (Figure 6F). This result implies that the linkers between the TM and periplasmic domains of OmpA are stabilized in the dimer such that its conformation is preserved in the gas phase without unfolding or collapse.

DISCUSSION

We have shown not only that FL-OmpA can form a population of dimers, but also that the dimerization interface is due to interactions between its highly conserved soluble CTD. As seen for the transmembrane and soluble constructs, the residues 188-276 are sufficient to maintain the same population of dimers as the FL-OmpA. The fact that the dimer is not the predominant species could arise from dissociation in the gas phase due to the activation required to remove the protein from the DDM micelle or due to instability in detergent micelles. However, the soluble constructs yielded the same relative amounts of dimer (~30%). The fact that in vivo cross-linking generates dimers only partially (Zheng et al., 2011) indicates that OmpA is in equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric states, as seen here. The presence of this oligomeric heterogeneity could explain the poor propensity of FL-OmpA to crystallize, hence the importance of understanding the structural basis of this equilibrium.

Our integrative modeling strategy based on MS, cross-linking constraints and CCS values determined by IM-MS enabled us to identify just two possible conformations for the C-terminal dimer out of the 795 models generated. Further analysis of truncated constructs and the determination of their propensity to form dimers by MS clearly showed that only one of these models is possible, since residues 277-325 cannot constitute the dimeric interface. When assembling the dimer of the CTD to the N-terminal β-barrels, the lack of information regarding the orientation of the barrels and the degree of folding/collapse of the linker leads to a low resolution model. However, the fact that the N-termini of the soluble domains are oriented in the same direction, and assuming that the barrels are parallel as anticipated in the membrane bilayer, this restricts the number of possibilities for assembling the FL dimer.

The good agreement between our model and the experimental CCS obtained for the FL-OmpA monomer with some unfolding and collapse and for the dimer without collapse indicates that the proposed models are plausible. It was surprising to see close similarity between our model for the FL-OmpA monomer, based on experimental data, and the one proposed from MD simulations of P. multocida OmpA (Khalid et al., 2008). The main difference between the two arises from the proline-rich linker between the β-barrel and the CTD, which consists of only four residues in P. multocida but 18 residues in E. coli OmpA. The larger freedom from the longer linker enables correct orienting of the CTD with respect to the N-terminal TM domains. However since both the N-terminal domains must be located in the membrane bilayer and the C-terminal domains are constrained by the location of the dimeric interface, their relative orientations are fixed, the only flexibility therefore arises from the unstructured linker.

The main question now remains to understand the physiological role of this population of dimers. The only 8-stranded β-barrels that have been shown to form dimers so far are the soluble enzymes RNA triphosphatase from yeast (Lima et al., 1999) and the bovine Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (Smith et al., 1992). To date no integral membrane 8-stranded β-barrel protein has been shown to exist as a dimer. Given the fact that OmpA plays a major role in maintaining the structural integrity of the outer membrane via interactions with peptidoglycans it is possible that the dimer helps stabilise this interaction. Alternatively, binding of such a ligand could change the dimerization surface. However, the binding site identified for the diaminopimelate, a bacterial amino acid from the peptidoglycan (Park et al., 2012), is not located at the dimeric interface identified in our model and these hypothesis would be interesting to consider for further work.

Additionally, the soluble domain of OmpA has been proposed to play a role in membrane conductance, with FL-OmpA forming large and small conductance channels, whereas TM-OmpA only exhibits small conductance (Arora et al., 2000). It has been suggested that, upon increase in temperature, the C-terminal domain of FL-OmpA refolds to extend the 8-stranded N-terminal barrel to form a 16-stranded barrel of higher conductance (Zakharian and Reusch, 2005). The fact that the truncated OmpA-1-276 and OmpA-188-276 were also able to form dimers, suggests that in the context of the dimer, the soluble domains are not integrating into this proposed 16-stranded pore.

Dimerization as a mechanism to regulate an enzymatic role is also plausible, as seen for the dimeric outer membrane phospholipase A (OmpLA) (Snijder et al., 1999). OmpA by contrast has no known enzymatic activity. An increasing number of studies on different species however have shown that OmpA can bind soluble proteins from the complement (Prasadarao et al., 2002) and dendritic cells to activate their production of cytokines (Pore et al., 2012; Soulas et al., 2000; Torres et al., 2006). Whether this role in the immune response, through the external loops, requires a change in the oligomeric state and potentially the stability of OmpA, is an attractive proposition that will require further investigation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and purification of OmpA constructs

Transmembrane constructs

The full-length and truncated OmpA constructs encompassing the transmembrane domain of OmpA were expressed in the OmpA- E. coli strain ΔlamB ompF: Tn5 ΔompAΔompC, using a pET1113 vector and purified as described previously (Kleinschmidt et al., 1999). The stop mutations at residues 188, 227 and 277 were inserted using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) and the mismatch nucleotides listed in Table S1. All constructs containing the TM domain were expressed in inclusion bodies, solubilised, and purified by ion exchange chromatography in 8M urea as described. The unfolded proteins were refolded by rapid dilution into DDM micelles. Typically 2-5 μl aliquots of a 10-25 mg/ml protein solution were diluted into 0.1 ml of a 5 mM DDM solution in 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0 buffer. The reaction was incubated at room temperature or 37°C for 16 hours. The final protein concentrations were approximately 0.5 mg/ml in 5 mM DDM.

Soluble constructs

The genes coding for the soluble constructs 188-325, 188-276 and 227-325 were subcloned into a modified pET28 vector using the Infusion HD Cloning kit (Clontech Laboratories Inc.) and the pET1113 vector as a template. The PCR products were obtained with the primers listed in Table S1 and cloned in the pET28 vector previously linearised with the restriction enzymes BamH1 and Xho1. All constructs were sequenced to confirm their identities. The soluble constructs were then transformed in E. Coli BL21-Gold (DE3) (Agilent Technologies), induced with 0.5 M IPTG and purified via their 6-His tag on a His Trap HP (GE Healthcare). Proteins were eluted from the column with 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole and then cleaved overnight with recombinant Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease. After removing the imidazole on Amicon concentrators (Millipore), the cleaved proteins were reloaded on the His Trap column in order to remove any uncleaved protein and the His-tagged TEV.

Native ion-mobility mass spectrometry

Prior to analysis, proteins were buffer exchanged in 200 mM ammonium acetate pH 7.4 (supplemented with 0.02 % DDM for transmembrane constructs) using Micro Bio-Spin 6 columns (Biorad). Samples were then loaded onto in-house prepared nano-flow capillaries (Hernandez and Robinson, 2007) and analysed on a quadrupole ion-mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Synapt HDMS, Waters) modified for the transmission of high MW complexes and to enable the measurement of collision cross section without previous calibration, as described elsewhere (Bush et al., 2010; Hall et al., 2012a). Mass spectra were calibrated externally using a 100 mg/ml solution of caesium iodide and analysed with MassLynx and Driftscope softwares (Waters). The theoretical CCSs were calculated using a scaled projection approximation method (Benesch and Ruotolo, 2011). Transmembrane proteins, requiring enough activation to dissociate from the DDM micelle, were sprayed using the following parameters: capillary, cone, extraction and trap voltages were set a 1.7 kV, 100 V, 0.8 V and 165 V, respectively with a backing pressure of 8.0 mbar. argon in the collision cell was set at 5.6 ml/min. Soluble constructs were sprayed with the following parameters: 1.6 kV, 20 V, 0.8 V and 10 V, respectively for the capillary, cone, extraction and trap voltage and 2 ml/min argon flow. In both cases the pressure in the mobility cell was set at 2.15 Torr with a 50 ml/min flow of helium and the temperature was monitored with a thermocouple (Omega Engineering). Drift times were acquired for drift voltages ramping from 50 to 150 V with 5-50 V steps.

Cross-linking

Proteins were first buffer exchanged in PBS pH 7.4 supplemented with 0.02 % DDM using Micro Bio-Spin columns and diluted to 10 μM. Samples were then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with 250 equivalents of EthyleneGlycol-di-Succinimidylsuccinate (EGS, Creative Molecules Inc.) in DMSO. Controls were incubated with an equivalent volume of DMSO. Samples were boiled for 15 min before loading on a NuPAGE Bis-Tris minigel (Invitrogen, CA, USA).

Description of the modeling steps

(1) A homology model of the CTD of E.coli was first generated with SwissModel, based on the CTD from S.Enterica (PDB 4ERH, 94% sequence homology). (2) Models for the dimer of the CTD were generated using the Symmdock algorithm with no binding site or distance restraint specified and the following parameters,: symmetryParams: 2 120 (to improve the sampling), scoreParams 0.1 −7.0 0.5 −4 −2 0 1 0 (to be more tolerant to steric clashes), clusterParams 0.1 2 1.0 (to allow small clusters). With these parameters, and a symmetry order of two (for a dimer), we obtained a maximum of 795 models. (3) These models were then filtered using distance restraints of 25 Å for the 4 cross-links described previously (Table S2). Of the 795 models, only 20 respected these 4 constraints. (4) The generated model structures were evaluated using a scoring scheme capable of measuring their closeness-of-fit to experimental CCS as described previously (Hall, et, 2012b: Politis, 2013). In brief, this scoring scheme is expressed as a harmonic function of the restrained feature (CCS), as described in eq. 1:

| eq. 1 |

σexp regulates the strength of the restraint and is determined by the uncertainty in the data. For CCS measurements, we use 2SDs from the mean (± 6%) as defined in a previous study (Hall, et al. 2012b). The scores measured for these models ranged from 41 for the best fit to 3 207 757 for the largest deviation (worst model). The 20 models that respected the cross-linking constraints had scores ranging between 205 and 2 303 755. After normalisation of these scores (Figure 5B), we found that the six best models showed a CCS score <1% of the highest score and 4.5% for the 7th. We selected these 6 best models for further modeling steps. (5) These 6 models were clearly clustered in two different orientations, as seen in Figure 5C and D. The cluster represented in Figure 5C showed a dimeric interface relying mainly on the 50 last amino acids which are not required for dimerization, as shown by native MS on the transmembrane and soluble constructs. The cluster in Figure 5D was thus selected for the last modeling step. (6) This model of the dimer of the CTD from E.coli was finally manually fused with Pymol to the missing transmembrane parts and linkers. The beta-barrels (PDB file 1G90) were first positioned in parallel, facing the dimeric model of the CTDs. The barrels and CTDs were then joined by two 18-residue linkers extracted from the NMR structure of OmpA from K.pneumoniae (PDB file 2K0L). This latter is the only structure available with such a long linker and the linker sequences are identical in the two species. The fact that the C-termini of the barrels are facing down and the N-termini of the CTDs are facing up greatly facilitated the fusion of the two domains with the linkers that are nearly linear. We are aware of the fact that these manual fusions are performed with many degrees of freedom, leading to some uncertainty. However, the purpose here is not to provide a high-resolution structure, but to propose a low-resolution arrangement of the dimeric FL-OmpA in order to better understand its overall structure. The fact that the experimental CCSs of the FL monomer and dimer agree very well with our models suggests that these models are fair representations of the monomer and dimer structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Arthur Laganowsky for the kind gift of the modified pET28 plasmid and Dr. Jonathan Hopper for critical reading. This work is funded by an ERC Advanced investigator award (IMPRESS) to CVR and by grant R01 GM52329 from the National Institutes of Health to LKT.

REFERENCES

- Arora A, Abildgaard F, Bushweller JH, Tamm LK. Structure of outer membrane protein A transmembrane domain by NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:334–338. doi: 10.1038/86214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A, Rinehart D, Szabo G, Tamm LK. Refolded outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli forms ion channels with two conductance states in planar lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1594–1600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AJ, Lioe H, Hilton GR, Baker LA, Rubinstein JL, Kay LE, Benesch JL. The polydispersity of alphaB-crystallin is rationalized by an interconverting polyhedral architecture. Structure. 2011;19:1855–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera NP, Isaacson SC, Zhou M, Bavro VN, Welch A, Schaedler TA, Seeger MA, Miguel RN, Korkhov VM, van Veen HW, et al. Mass spectrometry of membrane transporters reveals subunit stoichiometry and interactions. Nat Methods. 2009;6:585–587. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera NP, Zhou M, Robinson CV. The role of lipids in defining membrane protein interactions: insights from mass spectrometry. Trends Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesch JL, Ruotolo BT. Mass spectrometry: come of age for structural and dynamical biology. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond PJ, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Sansom MS. OmpA: a pore or not a pore? Simulation and modeling studies. Biophys J. 2002;83:763–775. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borysik AJ, Hewitt DJ, Robinson CV. Detergent release prolongs the lifetime of native-like membrane protein conformations in the gas-phase. J Am Chem Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ja401736v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush MF, Hall Z, Giles K, Hoyes J, Robinson CV, Ruotolo BT. Collision cross sections of proteins and their complexes: a calibration framework and database for gas-phase structural biology. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9557–9565. doi: 10.1021/ac1022953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmer DE, Hudgins RR, Jarrold MF. Naked Protein Conformations - Cytochrome-C in the Gas-Phase. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1995;117:10141–10142. [Google Scholar]

- De Mot R, Vanderleyden J. The C-terminal sequence conservation between OmpA-related outer membrane proteins and MotB suggests a common function in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, possibly in the interaction of these domains with peptidoglycan. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:333–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizot S, Buchanan SK. Structure of the OmpA-like domain of RmpM from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1027–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Z, Politis A, Bush MF, Smith LJ, Robinson CV. Charge-state dependent compaction and dissociation of protein complexes: insights from ion mobility and molecular dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 2012a;134:3429–3438. doi: 10.1021/ja2096859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Z, Politis A, Robinson CV. Structural modeling of heteromeric protein complexes from disassembly pathways and ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Structure. 2012b;20:1596–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez H, Robinson CV. Determining the stoichiometry and interactions of macromolecular assemblies from mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:715–726. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Szabo G, Tamm LK. Electrostatic couplings in OmpA ion-channel gating suggest a mechanism for pore opening. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:627–635. doi: 10.1038/nchembio827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid S, Bond PJ, Carpenter T, Sansom MS. OmpA: gating and dynamics via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1871–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Arnold K, Kunzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D387–392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Aulakh S, Paetzel M. The bacterial outer membrane beta-barrel assembly machinery. Protein Sci. 2012;21:751–768. doi: 10.1002/pro.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt JH, den Blaauwen T, Driessen AJ, Tamm LK. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli inserts and folds into lipid bilayers by a concerted mechanism. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi982465w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository of annotated three-dimensional protein structure homology models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D230–234. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Prasadarao NV. Outer membrane protein A and OprF: versatile roles in Gram-negative bacterial infections. FEBS J. 2012;279:919–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima CD, Wang LK, Shuman S. Structure and mechanism of yeast RNA triphosphatase: an essential component of the mRNA capping apparatus. Cell. 1999;99:533–543. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, Robinson CV. Twenty years of gas phase structural biology. Structure. 2013;21:1541–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, Wang SC, Politis A, Reading E, Ma J, Biggin PC, Zhou M, Tao H, Zhang Q, Chang G, et al. Mass spectrometry reveals synergistic effects of nucleotides, lipids, and drugs binding to a multidrug resistance efflux pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303888110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel K, Natan E, Hall Z, Fersht AR, Robinson CV. Intrinsically disordered p53 and its complexes populate compact conformations in the gas phase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:361–365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Lee WC, Yeo KJ, Ryu KS, Kumarasiri M, Hesek D, Lee M, Mobashery S, Song JH, Kim SI, et al. Mechanism of anchoring of OmpA protein to the cell wall peptidoglycan of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. FASEB J. 2012;26:219–228. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-188425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautsch A, Schulz GE. Structure of the outer membrane protein A transmembrane domain. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politis A, Park AY, Hall Z, Ruotolo BT, Robinson CV. Integrative modelling coupled with ion mobility mass spectrometry reveals structural features of the clamp loader in complex with single-stranded DNA binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pore D, Mahata N, Chakrabarti MK. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) of Shigella flexneri 2a links innate and adaptive immunity in a TLR2-dependent manner and involvement of IL-12 and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12589–12601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.335554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Prasadarao NV, Blom AM, Villoutreix BO, Linsangan LC. A novel interaction of outer membrane protein A with C4b binding protein mediates serum resistance of Escherichia coli K1. J Immunol. 2002;169:6352–6360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionova NA, Tatulian SA, Surrey T, Jahnig F, Tamm LK. Characterization of two membrane-bound forms of OmpA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1921–1929. doi: 10.1021/bi00006a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruotolo BT, Benesch JL, Sandercock AM, Hyung SJ, Robinson CV. Ion mobility-mass spectrometry analysis of large protein complexes. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1139–1152. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruotolo BT, Giles K, Campuzano I, Sandercock AM, Bateman RH, Robinson CV. Evidence for macromolecular protein rings in the absence of bulk water. Science. 2005;310:1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1120177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint N, De E, Julien S, Orange N, Molle G. Ionophore properties of OmpA of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1145:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90388-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. Geometry-based flexible and symmetric protein docking. Proteins. 2005a;60:224–231. doi: 10.1002/prot.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005b;33:W363–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Carson M, van der Woerd M, Chen J, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Crystal structure of peroxynitrite-modified bovine Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;299:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder HJ, Kingma RL, Kalk KH, Dekker N, Egmond MR, Dijkstra BW. Structural investigations of calcium binding and its role in activity and activation of outer membrane phospholipase A from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:477–489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder HJ, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Blaauw M, Kalk KH, Verheij HM, Egmond MR, Dekker N, Dijkstra BW. Structural evidence for dimerization-regulated activation of an integral membrane phospholipase. Nature. 1999;401:717–721. doi: 10.1038/44890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag I, Schwarz H, Hirota Y, Henning U. Cell envelope and shape of Escherichia coli: multiple mutants missing the outer membrane lipoprotein and other major outer membrane proteins. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:280–285. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.1.280-285.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulas C, Baussant T, Aubry JP, Delneste Y, Barillat N, Caron G, Renno T, Bonnefoy JY, Jeannin P. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) binds to and activates human macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:2335–2340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg F, Chovanec P, Maslen SL, Robinson CV, Ilag LL, von Heijne G, Daley DO. Protein complexes of the Escherichia coli cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34409, 34419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara E, Nikaido H. Pore-forming activity of OmpA protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2507–2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara E, Nikaido H. OmpA protein of Escherichia coli outer membrane occurs in open and closed channel forms. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17981–17987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara E, Nikaido H. OmpA is the principal nonspecific slow porin of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4089–4096. doi: 10.1128/JB.00435-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AG, Li Y, Tutt CB, Xin L, Eaves-Pyles T, Soong L. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli O157:H7 stimulates dendritic cell activation. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2676–2685. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2676-2685.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SC, Politis A, Di Bartolo N, Bavro VN, Tucker SJ, Booth PJ, Barrera NP, Robinson CV. Ion mobility mass spectrometry of two tetrameric membrane protein complexes reveals compact structures and differences in stability and packing. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15468–15470. doi: 10.1021/ja104312e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharian E, Reusch RN. Kinetics of folding of Escherichia coli OmpA from narrow to large pore conformation in a planar bilayer. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6701–6707. doi: 10.1021/bi047278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Yang L, Hoopmann MR, Eng JK, Tang X, Weisbrod CR, Bruce JE. Cross-linking measurements of in vivo protein complex topologies. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110 006841. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Morgner N, Barrera NP, Politis A, Isaacson SC, Matak-Vinkovic D, Murata T, Bernal RA, Stock D, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry of intact V-type ATPases reveals bound lipids and the effects of nucleotide binding. Science. 2011;334:380–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1210148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Politis A, Davies RB, Liko I, Wu KJ, Stewart AG, Stock D, Robinson CV. Ion mobility-mass spectrometry of a rotary ATPase reveals ATP-induced reduction in conformational flexibility. Nat Chem. 2014;6:208, 215. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.