Abstract

Background

Our preliminary data on the protein expression of SORT1 in ovarian carcinoma tissues showed that sortilin was overexpressed in ovarian carcinoma patients and cell lines, while non-malignant ovaries expressed comparably lower amount of this protein. In spite of diverse ligands and also different putative functions of sortilin (NTR3), the function of overexpressed sortilin in ovarian carcinoma cells is an intriguing subject of inquiry. The aim of this study was, therefore, to investigate the functional role of sortilin in survival of ovarian carcinoma cell line.

Methods

Expression of sortilin was knocked down using RNAi technology in the ovarian carcinoma cell line, Caov-4. Silencing of SORT1 expression was assessed using real-time qPCR and Western blot analyses. Apoptosis induction was evaluated using flow cytometry by considering annexin-V FITC binding. [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay was also used to evaluate cell proliferation capacity.

Results

Real-time qPCR and Western blot analyses showed that expression of sortilin was reduced by nearly 70-80% in the siRNA transfected cells. Knocking down of sortilin expression resulted in increased apoptosis (27.5±0.48%) in siRNA-treated ovarian carcinoma cell line. Sortilin silencing led to significant inhibition of proliferation (40.1%) in siRNA-transfected Caov-4 cells as compared to mock control-transfected counterpart (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

As it was suspected from overexpression of sortilin in ovarian tumor cells, a cell survival role for sortilin can be deduced from these results. In conclusion, the potency of apoptosis induction via silencing of sortilin expression in tumor cells may introduce sortilin as a potential candidate for developing a novel targeted therapy in patients with ovarian carcinoma.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cancer, Ovary, Silencing, siRNA, Sortilin

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most lethal gynecologic malignancies. In spite of the significant advances in the treatment of this can cer, 40 to 85% of patients with stage II-IV relapse after primary therapy (1). Different strat-egies have been used in patients with advanced ovarian cancer to prolong the short-term survival achieved after chemotherapy (2). To this end, some antigens such as cancer antigen 125 (CA125), glycoprotein 38 (gp38), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), Mucin 1 (MUC1), Tumor-associated Glycoprotein 72 (TAG-72), ovarian carcinoma antigen 3 (OA3), mesothelin, cancer/testis antigen 1B (CTAG1B) (NY-ESO-1), and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) have been targeted for immunotherapeutic treatments of ovarian cancer patients (3), (4). However, developing novel and more effective therapeutic approaches is a prerequisite for significant improvement of current therapeutic outcomes in these patients (4).

The gene encoding human sortilin (SORT1) has been mapped to the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p21.3-p13.1). It consists of 22 exons. The open reading frame encodes a protein of 833 amino acids containing an N-terminal signal peptide, a putative cleavage site for furin, a long luminal domain, a single transmembrane part, and a short cytoplasmic tail (5).

Information at the molecular and cellular levels confirms that sortilin performs a dual function, pro-apoptotic versus anti-apoptotic, in different kinds of non-malignant and cancerous cells expressing this molecule. Sortilin has been known as a non-G-protein coupled Neurotensin Receptor 3 (NTR3) which serves as a scavenger receptor to eliminate Neurotensin (NT) from the extracellular fluid by endocytosis and triggers its degradation. The endogenous co-expression of sortilin/NTR3 and NT in human prostate, colon, and pancreas cancers implies the role of this receptor in growth response induced by NT in an auto-crine manner (6). Conversely, simultaneous binding of the pro-domain of pro-neurotrophins to sortilin and the mature part of pro-neurotro-phins to its partner, p75NTR, induces cell death in brain (7). Thus, sortilin acts as a co-receptor and molecular switch governing the p75NTR-mediated pro-apoptotic signal induced by proNGF (8).

The first molecular characterization of sortilin by Petersen et al revealed that it is expressed at the gene level in heart, brain, placenta, skeletal muscle, testis, thyroid, and spinal cord (9). Gene expression profiling of 37 late stage serous ovarian carcinoma tissues has shown a nearly four-fold increase of SORT1 gene expression as compared to six non-malignant ovarian surface epithelium (10). Previous data from our group demonstrated that sortilin was overexpressed in a panel of ovarian carcinoma tissues as compared to non-malignant tissues (11). To assess the potential application of sortilin as a novel therapeutic target in ovarian cancer, this assessment was expanded to more ovarian tissue samples in the current study. The results showed that sortilin is overexpressed in ovarian carcinoma patients and cell lines, while non-malignant ovaries expressed a comparably lower amount of sortilin. This achievement may represent the potential role of sortilin in ovarian tumori-genesis. In spite of the diversity of ligands and also different putative functions of sortilin/ NTR3, the potential role of overexpressed sortilin in ovarian carcinoma cells is an intriguing subject of inquiry.

RNA interference (RNAi) provides a new and reliable method to investigate gene function and has many advantages over other nucleic acid-based approaches (12). This technique is currently the most widely used gene-si-lencing modality in functional genomics (12). By taking advantage of siRNA technology, the aim of this study was silencing SORT1 expression in the ovarian carcinoma cell line, Caov-4, as a model to investigate the functional role of sortilin in survival of ovarian carcinoma cells.

Materials and Methods

Specimen collection

Tissue samples from seven patients with ovarian carcinoma, pathologically diagnosed as serous adenocarcinoma (n = 5; mean age 54.8 yr), endometrioid carcinoma (n = 1; 39 yr), or mucinous carcinoma (n = 1; 59 yr), and five non-malignant ovarian tissues (mean age 45.3 yr, undergone surgery for ovarian cysts) were obtained from Imam Khomeini Hospital (Tehran, Iran) (Table 1). Each individual signed an informed consent and all aspects of this study were approved by Avicenna local ethics committee. After surgical resection, each fresh tissue specimen was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for further study. Tissue sections were taken from each sample, stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), and examined by a pathologist to confirm their path-ological state.

Table 1.

Demographic data of seven ovarian carcinoma patients and five non-malignant controls

| Tissue Samples | Morphology | Type of differentiation | Age (yr) | Stage | CA125 level (U/ml) | Level of differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC1 | Epithelial | Serous adenocarcinoma | 67 | IV | 1515 | Moderate |

| OC2 | Epithelial | Serous adenocarcinoma | 33 | I | >1000 | Well |

| OC3 | Epithelial | Serous adenocarcinoma | 65 | NA | >1000 | Well/Moderate |

| OC4 | Epithelial | Endometrioid | 39 | III | 78 | Moderate |

| OC5 | Epithelial | Serous adenocarcinoma | 68 | II | >1000 | NA |

| OC6 | Epithelial | Mucinous | 59 | NA | 205 | NA |

| OC7 | Epithelial | Serous adenocarcinoma | 40 | III | 214 | Well |

| Non-malignant Ovary (n = 5) | Cystic ovarian tissues | ₋ | 40-49 | ₋ | NA | ₋ |

OC: Ovarian Carcinoma, NA: Not Assigned

Cell lines and culture conditions

The ovarian carcinoma cell lines including Caov-4 (HTB-76), OVCAR-3 (HTB-161), SKOV-3 (HTB-77) (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), A2780S (C461) and 2008/C13.R (C446) (National Cell Bank of Iran) were cultured in their optimal conditions in RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland), containing 10% FBS (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland), 100 units/ml penicillin (ICN Biomedicals, Ohio) and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere.

siRNA transfection

The siRNA against SORT1 and mock control (non-targeting control) were purchased from Thermo Scientific Company (Lafayette, CO, USA). siRNA reagent against SORT1 consisted of a pool of four siRNA oligonucleotides with the following sequences:

GAGACUAUGUUGUGACCAA;

GAGCUAGGUCCAUGAAUAU;

GAAGGACUAUACCAUAUGG;

GAAUUUGGCAUGGCUAUUG.

The non-targeting control was used as a negative mock control to eliminate background of siRNA transfection. Suppression of SORT1 expression was performed in Caov-4 cells, which had been trypsinized and seeded 24 hr prior to transfection, either in 12-well plates (2×105 cells/well for RNA extraction and Western blot analysis) or in 96-well plates (2×104 cells/well for proliferation and apoptosis assays). On the day of transfection, cells were 70% confluent. siRNA or mock control transfection was carried out at a final concentration of 200 nM using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The optimal duration and efficiency of the transfection process was optimized using fluorescein-labeled siRNA. The expression level of targeted SORT1 mRNA was controlled by real-time quantitative PCR at 24 and 48 hr after transfection. Western blot analysis at 48, 72, and 96 hr after transfection was performed to assess the protein expression decline.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from transfected and untransfected cultured cells using RNA-Bee reagent (BioSite, Täby, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First strand cDNA was synthesized using 2 µg of total RNA in a 20 µl reaction mixture consisting of 4 µl of a 5× reaction buffer, 2 µl of 10 mM dNTP, 1 µl of 20 pmol/µl random hexamer primer (N6) and 20 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). The reaction was performed at 42°C for 60 min.

Quantification of SORT1 transcript by real-time quantitative RT-PCR

All real-time quantitative PCRs were performed by an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), utilizing SYBR Green reagents (Takara, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification of PCR products was quantified during PCR by measuring fluorescence associated with binding of SYBR Green dye incorporated into the reaction mixture to double-stranded DNA. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used in PCR-amplification of SORT1 and β-actin as housekeeping gene, were S: 5′-CAGTCCAAGCTATATCGAAG TGAGG-3′, AS:5′-AAGATGGTGTTGTCTG ATCCCCATTT-3′ and S: 5′-AGCCTCGCCT TTGCCGA-3′, AS: 5′-CTGGTGCCTGGGG CG-3′, respectively (13). Each PCR was performed in a 20 µl total volume mixture containing 10 µl of SYBR® Premix Ex Taq (2×), 0.4 µl of ROX Reference Dye (50×), 500 nM of each primer, and 2 µl of 1:2 diluted cDNA samples. Following an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 10 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 1.5 min, for both SORT1 and β-actin, the reaction was performed. Relative expression of SORT1 mRNA was calculated with the following formula:

R=(Etarget) ΔCTtarget/(Ereference) ΔCTreference

Data were analyzed for significant differences (p < 0.05) by pair wise fixed reallocation randomization test using REST© software (14).

Western blotting

Tissue samples and cell lines were lysed in a buffer containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris, pH = 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH = 8, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 1% (v/v) Glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail. For analysis of sortilin expression after RNAi technology, siRNA- or mock control- transfected cells were harvested 48, 72 and 96 hr post-transfection and lysed in the aforesaid lysis buffer. The protein concentration was estimated by a bicinchorinic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockfold, Illinois). Equal amounts of protein (15 µg) were run on SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis and electroblotting (11), membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-human sortilin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at a concentration of 1 µg/ml, or with 1:2000 diluted mouse anti-human β-actin (Sigma).

After washing steps, membranes were incubated either with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit immunoglobulin or with sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Avicenna Research Institute, Tehran, Iran) diluted 1:2000. Filters were developed using the ECL advanced system (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). For densitometry analysis of protein bands, AlphaEase software was used. The contrast was adjusted so that black and white colors were corresponded to 250 and 0, respectively. Using a rectangular selection, bands were then selected. Relative expression of sortilin was presented as the percentage values from sortilin/ β-actin density ratio. Reduction of sortilin expression following siRNA treatment was calculated at different hours post-transfection using the following formula:

[sortilin (mock)/β-actin (mock)-sortilin (siRNA)/β-actin (siRNA)]×100

Study of apoptosis

Apoptosis in Caov-4 cells transfected with siRNA or mock control and also untreated control cells was measured at different time points (48, 72, and 96 hr after transfection). Cells were scraped, washed twice in PBS and centrifuged. Pelleted cells were incubated in 1× binding buffer containing FITC-annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in dark for 15 min. Apoptotic cells were examined using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using the FlowJo software (version 7.6.1). A minimum of 1×104 events per sample were acquired and analyzed. Three independent experiments were performed. Values were expressed as the mean±SEM in 3 separate experiments.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Caov-4 cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in 96-well plates (Costar Corporation, Cambridge, MA). Twenty eight hours after transfection, 1 µci/well [3H]-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) was added to the media of siRNA-or mock control- transfected cells, untransfected cells (as positive control) and staurosporine-treated (5 µM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) cells (as negative control). Cells were then allowed to propagate for 20 hr followed by harvesting onto filter papers (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Radioactive incorporation was measured in a 1450 Micro-beta TriLux Scintillator (Wallac, Turku, Finland) and expressed as counts per minute (CPM). All tests were performed with 6 replicates in two independent experiments. The proliferation index was calculated for each experiment as:

(Mean CPM of transfected cells/Mean CPM of untransfected cells)×100.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney test was used to determine the statistical significance (p < 0.05) between experimental groups. Values were expressed as the mean±SEM.

Results

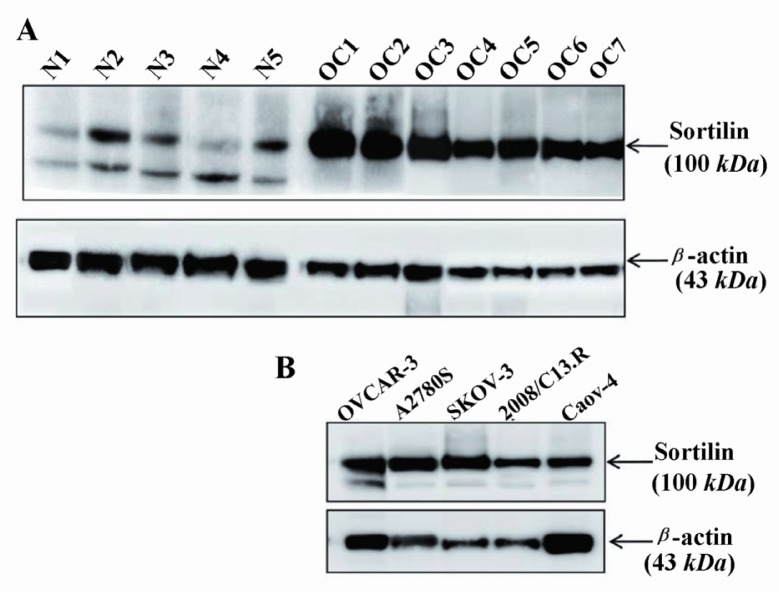

Sortilin protein expression

Basal level of sortilin protein expression was investigated by Western blot analysis. The results clearly showed that all the primary ovarian carcinoma tissues as well as ovarian carcinoma cell lines, namely A2780S, 2008/ C13.R, OVCAR-3, Caov-4 and SKOV-3, over-expressed sortilin with a strong band of about 95-100 kDa (Figures 1A and 1B). Although all non-malignant ovarian tissues expressed sortilin, the level of expression was comparably low (Figure 1A). Interestingly, a band was observed at about 80-85 kDa molecular weight in all non-malignant ovarian tissues, corresponding to the size of the second protein-coding variant of sortilin containing 694 amino acids. The 80-85 kDa form of sortilin results from the missing of the first N-terminal 137 amino acids (nearly 15 kDa) following a reading frame shift in the main transcript variant containing 831 amino acids (95-100 kDa) (http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Transcript/Sequence_cDNA?g=ENSG00000134243;r=1:109869428-109878924;t=ENST00000466471).

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of sortilin expression in ovarian cancer and non-malignant tissues. Seven ovarian carcinoma tissues (Table 1) as well as five ovarian carcinoma cell lines that overexpressed sortilin were compared with five non-malignant ovarian tissues (A and B). The lower band in non-malignant ovarian tissues is likely to be related to the second variant of sortilin with a molecular weight of 80-85 kDa. The level of β-actin as an internal protein loading control was detected in each sample. OC: ovarian carcinoma tissue, N: non-malignant ovarian tissue

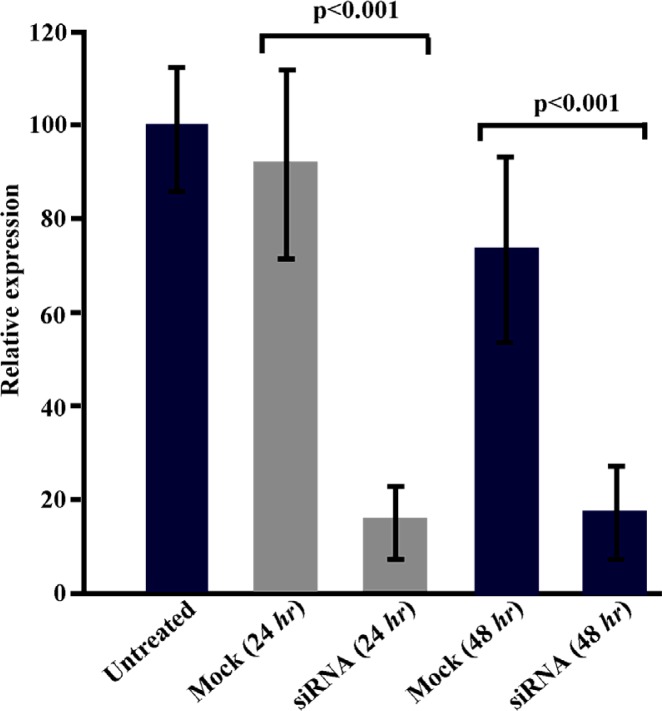

Suppression of sortilin expression by RNAi

The ability of siRNA to inhibit expression of sortilin in Caov-4 cell line was determined using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (24 and 48 hr after transfection) and Western blotting (48, 72 and 96 hr after transfection). The siRNA transfection significantly (p < 0.001) suppressed the expression of SORT1 in Caov-4 cells. Analysis of real-time quantitative RT-PCR revealed a 6.1 fold reduction in the relative expression of SORT1 in the siRNA-transfected sample as compared with the mock control 24 hr post-transfection (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The reduction of SORT1 transcript in siRNA-transfected cells continued 48 hr post-transfection in which a 4.2 fold reduction was observed (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of SORT1 expression in Caov-4 cells following siRNA treatment. Results revealed 6.1 fold and 4.2 fold reduction in SORT1 expression in siRNA-transfected cells as compared to mock control-transfected cells 24 and 48 hr post-transfection, respectively (p < 0.001). Values are presented as mean±SEM in 3 separate experiments

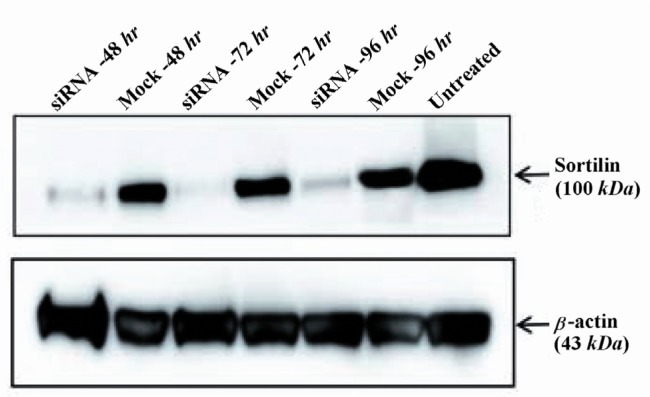

Real-time quantitative PCR results were confirmed by Western blotting at the protein level. The siRNA transfection of Caov-4 cells caused a significant decrease in the amount of sortilin protein expression. Densitometric analysis by AlphaEaseFC software showed that the level of sortilin was reduced by 72, 69 and 61% in siRNA-treated Caov-4 cells as compared with mock controls, 48, 72 and 96 hr post-transfection, respectively (Figure 3). The level of sortilin expression 24 hr post-transfection showed no reduction as compared to control (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of sortilin protein levels in siRNA-transfected cells. Densitometric analysis showed that the level of sortilin was markedly reduced by 72, 69 and 61% in siRNA-treated cells as compared to mock control-treated cells at 48, 72 and 96 hr after transfection, respectively. The level of β-actin as an internal protein loading control was detected in each sample

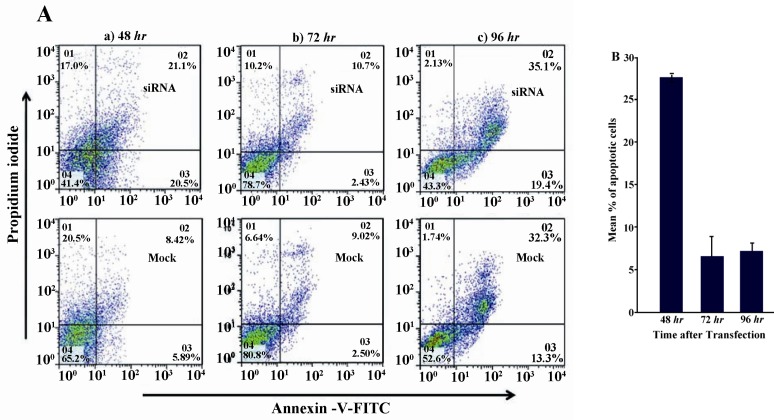

Apoptosis induction by suppression of sortilin expression

Next, the effect of suppression of sortilin expression on survival of Caov-4 cells was examined using FACS analysis of annexin V staining 24, 48 and 72 hr post-transfection. In each individual experiment, the percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as the sum of percentages of cells in early (i.e., annexin V-positive, PI-negative) and late (i.e., annexin V-positive, PI-positive) stages of apoptosis and was subtracted from those of mock control-transfected cells. The results showed that suppression of sortilin induced 27.5±0.48 apoptosis of Caov-4 cells 48 hr after siRNA transfection when compared to mock control-transfected cells (Figures 4A and 4B). The level of apoptosis decreased over time after transfection. As compared to mock control-transfected cells, the siRNA-treated cells showed 6.4±2.4% and 7.3±0.9% apoptosis at 72 and 96 hr after transfection, respectively (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of apoptosis following down regulation of sortilin expression. A) Caov-4 cells were treated with sortilin siRNA or mock control and the levels of apoptosis were then evaluated by annexin V FACS analysis 48, 72 and 96 hr post-transfection. The picture shows one of the three experiments. B) Numerical results from three independent experiments of FACS analysis of annexin V staining. Values are presented as mean±SEM in 3 separate experiments

Effect of sortilin silencing on proliferative capacity

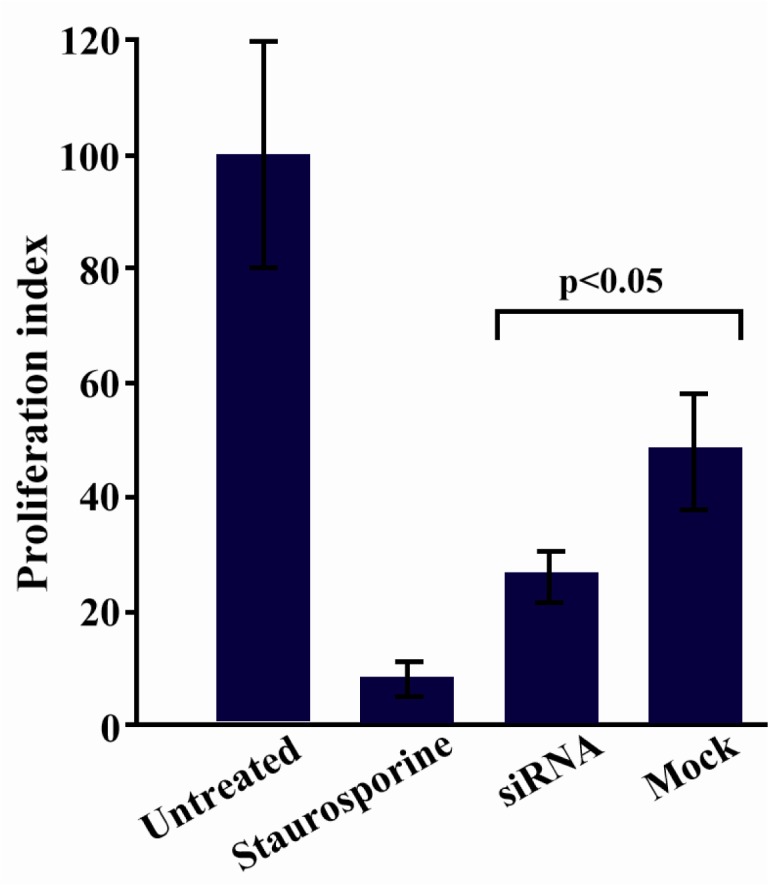

Proliferation assay using [3H]-thymidine was carried out 48 hr after transfection (a time point in which the maximum apoptosis induction was achieved) to evaluate the influence of sortilin silencing on the proliferative capacity of siRNA-transfected cells. Results from this experiment clearly confirmed those obtained from apoptosis analysis. Sortilin silencing resulted in significant inhibition of proliferation (40.1%) in siRNA-transfected Caov-4 cells as compared to mock control-transfected counterpart (p < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Assessment of cell proliferation following sortilin down regulation. Cell proliferation was inhibited (40.1%) in siRNA-transfected Caov-4 cells as compared to mock control-transfected counterpart 48 hr post-transfection (p < 0.05). Data is represented as mean±SEM in 2 independent experiments with 6 replicates

Discussion

In the present study, the expression pattern of sortilin was characterized in a panel of human ovarian carcinoma cell lines and tissues. All ovarian carcinoma tissues and cell lines exhibited substantially higher levels of sortilin expression as compared to non-malignant ovarian tissues. Interestingly, all non-malignant ovarian tissues expressed the 80-85 kDa variant of sortilin while no expression of this variant was seen in ovarian carcinoma tissues. This pattern may probably imply that main variant of sortilin (95-100 kDa) contributes in sustaining cell survival, while the small variant (80-85 kDa) has a counter-regulatory activity.

It is well established that sortilin or NTR-3 has a functional role in the internalization of NT and subsequent cell growth (15). Overexpression of this receptor in ovarian cancer cells, as it was shown, raises the idea that sortilin may have a role in survival of ovarian tumors. To address this notion, RNAi approach was utilized to down regulate sortilin expression in Caov-4 cells as an ovarian cancer cell line. The results clearly showed that following siRNA transfection, a considerable decline in sortilin level was occurred 48 hr post-transfection, a time point in which maximum apoptosis induction was also achieved. The results of proliferation assay confirmed those of the apoptosis assay, and therefore supported the hypothesis that sortilin may trigger survival signals leading to tumor growth and augmented cell proliferation.

The data presented in this paper are consistent with the finding that pointed out the survival role of sortilin on under-stress B cells through its function in transportation and secretion of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) (16). Moreover, direct evidence for the potential role of sortilin in cell growth stimulation has been provided by Dal Farra et al (15), who observed stimulation of DNA synthesis in NTR3-expressing CHO cells in the presence of NT. Recently, it has also been speculated that sortilin acts as a positive modulator of neurotrophin-induced neuronal survival (17). In neuronal cells, sortilin facilitates trophic signaling by ensuring adequate Trk receptor expression at the synapse for mature neuro-trophins to stimulate neuronal survival and differentiation (17).

The existence of a heterodimerization between NTR3 and NTR1 has been already described in the human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line, HT29, which leads to modulation of the intracellular events induced by NT (18). Moreover, NT acts as a growth factor on a variety of human cancer cell lines derived from lung, colon, prostate and pancreas (15).

Indeed, tumor cells can both secrete NT and express NT receptors, suggesting auto-crine and paracrine regulation of cell growth by NT (19). Interestingly, stimulation of HT29 cells with NT resulted in ligand-induced internalization of NTR3/NT complexes suggesting that contribution of NTR3 might be more important than NTR1 in the process of NT internalization (20). Nonetheless, the cell surface hetero-dimerization of NTR1 and NTR3 in colon carcinoma cells in modulation of NT internalization (18) inspires further investigation for finding NTR1 expression in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines.

Some evidence like phosphorylation of both extracellular signaling-regulated kinases Erk1/2 and Akt in microglia cells following NT-mediated sortilin/NTR3 signaling pathway (21), and subsequent increased motility and chemokines/cytokines expression by these cells (22) may indicate a more tangible role of sortilin in cancer metastasis. Similarly, the role of sortilin plus TrkA in the invasion of breast cancer cells has been demonstrated through release of proNGF from these cells in an autocrine manner (23).

Considering the above findings, it can be assumed that sortilin may act as a cell survival receptor in ovarian cancer through internalizing NT and triggering subsequent anti-apoptotic signals. Further biochemical experiments such as photoaffinity labeling using 125I-azido-NT and confocal microscopic observation are needed before making a firm judgment on the potential role of sortilin in ovarian cancer growth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the finding of decreased cell survival and increased apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells following down regulation of sortilin, highlights the pivotal role of this receptor in ovarian cancer growth and survival. Although the transduction pathways of sortilin have not been completely elucidated yet and therefore it is difficult to speculate on the exact mechanisms of apoptosis in sortilin deficient cells, suppression of its expression may signify a therapeutic value in targeted therapy of ovarian carcinoma. Obviously, further studies are needed to develop a more robust link between sortilin expression and survival of ovarian cancer. Therefore, generation of mo-noclonal antibodies capable of competing with sortilin ligand binding site (Vps10p domain) and thereby inducing apoptosis in ovarian tumor cells is our future plan.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Zohreh Sadeghian (Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran) for her assistance in collecting tissue samples. This article is derived from part of Ph.D., dissertation entitled“Studying the role of SORT1 in survival of ovarian cancer cell line”.

References

- 1.Tinger A, Waldron T, Peluso N, Katin MJ, Dosoretz DE, Blitzer PH, et al. Effective palliative rad-iation therapy in advanced and recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51(5):1256–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velasco AP, Herraez AC, Ruiperez AC, Rincon DG, Garcia EG, Martin AG, et al. Treatment guide-lines in ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9(5):308–316. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu B, Nash J, Runowicz C, Swede H, Stevens R, Li Z. Ovarian cancer immunotherapy: opportunities, progresses and challenges. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oei AL, Sweep FC, Thomas CM, Boerman OC, Massuger LF. The use of monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer (review) Int J Oncol. 2008;32(6):1145–1157. doi: 10.3892/ijo_32_6_1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent JP, Mazella J, Kitabgi P. Neurotensin and neurotensin receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20(7):302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazella J, Vincent JP. Functional roles of the NTS2 and NTS3 receptors. Peptides. 2006;27(10):2469–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willnow TE, Petersen CM, Nykjaer A. VPS10P-domain receptors-regulators of neuronal viability and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):899–909. doi: 10.1038/nrn2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nykjaer A, Lee R, Teng KK, Jansen P, Madsen P, Nielsen MS, et al. Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature. 2004;427(6977):843–848. doi: 10.1038/nature02319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen CM, Nielsen MS, Nykjaer A, Jacobsen L, Tommerup N, Rasmussen HH, et al. Molecular identification of a novel candidate sorting receptor purified from human brain by receptor-associated protein affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(6):3599–3605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donninger H, Bonome T, Radonovich M, Pise-Masison CA, Brady J, Shih JH, et al. Whole genome expression profiling of advance stage papillary serous ovarian cancer reveals activated pathways. Oncogene. 2004;23(49):8065–8077. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmati S, Zarnani AH, Mahmoudi AR, Sadeghi MR, Soltanghoraee H, Akhondi MM, et al. Ectopic expression of sortilin 1 (NTR-3) in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2009;1(2):125–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorsett Y, Tuschl T. siRNAs: applications in functional genomics and potential as therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(4):318–329. doi: 10.1038/nrd1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreuzer KA, Lass U, Landt O, Nitsche A, Laser J, Ellerbrok H, et al. Highly sensitive and specific fluorescence reverse transcription-PCR assay for the pseudogene-free detection of beta-actin transcripts as quantitative reference. Clin Chem. 1999;45(2):297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(9):e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dal Farra C, Sarret P, Navarro V, Botto JM, Mazella J, Vincent JP. Involvement of the neurotensin receptor subtype NTR3 in the growth effect of neurotensin on cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2001;92(4):503–509. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauchais AL, Lalloue F, Lise MC, Boumediene A, Preud'homme JL, Vidal E, et al. Role of endo-genous brain-derived neurotrophic factor and sortilin in B cell survival. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3027–3038. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaegter CB, Jansen P, Fjorback AW, Glerup S, Skeldal S, Kjolby M, et al. Sortilin associates with Trk receptors to enhance anterograde transport and neurotrophin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(1):54–61. doi: 10.1038/nn.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin S, Navarro V, Vincent JP, Mazella J. Neurotensin receptor-1 and -3 complex modulates the cellular signaling of neurotensin in the HT29 cell line. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1135–1143. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carraway RE, Plona AM. Involvement of Neurotensin in cancer growth: evidence, mechanisms and development of diagnostic tools. Peptides. 2006;27(10):2445–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morinville A, Martin S, Lavallee M, Vincent JP, Beaudet A, Mazella J. Internalization and trafficking of neurotensin via NTS3 receptors in HT29 cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(11):2153–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin S, Dicou E, Vincent JP, Mazella J. Neurotensin and the neurotensin receptor-3 in microglial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81(3):322–326. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin S, Vincent JP, Mazella J. Involvement of the neurotensin receptor-3 in the neurotensin- induced migration of human microglia. J Neurosci. 2003;23(4):1198–1205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01198.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demont Y, Corbet C, Page A, Ataman-Onal Y, Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Fliniaux I, et al. Pro-nerve growth factor induces autocrine stimulation of breast cancer cell invasion through tropomyosin-related kinase A (TrkA) and sortilin protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):1923–1931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]