Abstract

Background

To elucidate the relationship between safety culture maturity and safety performance of a particular company.

Methods

To identify the factors that contribute to a safety culture, a survey questionnaire was created based mainly on the studies of Fernández-Muñiz et al. The survey was randomly distributed to 1000 employees of two oil companies and realized a rate of valid answer of 51%. Minitab 16 software was used and diverse tests, including the descriptive statistical analysis, factor analysis, reliability analysis, mean analysis, and correlation, were used for the analysis of data. Ten factors were extracted using the analysis of factor to represent safety culture and safety performance.

Results

The results of this study showed that the managers' commitment, training, incentives, communication, and employee involvement are the priority domains on which it is necessary to stress the effort of improvement, where they had all the descriptive average values lower than 3.0 at the level of Company B. Furthermore, the results also showed that the safety culture influences the safety performance of the company. Therefore, Company A with a good safety culture (the descriptive average values more than 4.0), is more successful than Company B in terms of accident rates.

Conclusion

The comparison between the two petrochemical plants of the group Sonatrach confirms these results in which Company A, the managers of which are English and Norwegian, distinguishes itself by the maturity of their safety culture has significantly higher evaluations than the company B, who is constituted of Algerian staff, in terms of safety management practices and safety performance.

Keywords: safety behavior, safety culture, safety management, safety performance

1. Introduction

The term “safety culture” appears to have been first used after the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. The investigation report by the International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group (INSAG) of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) pinpointed “poor safety culture” as one of the contributing factors to this worst nuclear power plant accident in history. Although the concept of safety culture has been used more often in safety research, particularly in high-risk industries such as e nuclear power, oil, gas, chemical, construction, etc. [1], not much research has examined the relationship between safety culture and safety performance. Recently, many industries showed a growing interest in safety culture concept as a means of potential accident reduction associated with unforeseen working situations and as in the ordinary tasks [2]. Safety culture is the main indicator of safety performance [3].

The safety culture is a polemical and complex concept which requires the theoretical and empirical clarification [4]. Several definitions have been attributed to the safety culture concept [2,5–9]. Nevertheless, most of them are wide ranging and implicit. The safety culture has been defined as the product of interactions between people (psychological factors), jobs (behavioral factors), and the organization (situational factors) [10]. It recognizes explicitly that this tripartite interaction is also represented in the definition given by Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations [11].

Cooper [2] considers those attitudes, perceptions, and faiths of individuals, their behavior, and the safety management systems as well as the situational objective characteristics as the constituents of the safety culture of the organization.

Fernández-Muñiz et al [12] consider the culture of safety as a component of the organizational culture that refers to the individuals, to the work, and to the organizational characteristics that can affect their health and safety. The purpose of a positive safety culture is to create an atmosphere in which the employees know the risks to which they are exposed in their workplace and the means of protection.

The culture of safety is an important management tool in checking the faiths, the attitudes, and behavior of the employees regarding safety.

According to Lefranc et al [13], safety culture is based on three main components: behavioral, organizational, and psychological. There seems be a consensus suggesting that the organizational and contextual factors are important in the safety culture definition. The psychological component aims to analyze the attitudes and perceptions of the individual and the group. The behavioral component evaluates external factors (wearing Personal protective equipment (PPE), following operating procedures, etc.) applicable to individuals in the field and observable behavior. Finally, the organizational component corresponds to an analysis of business operations through its policies, procedures, and structures.

In summary, although a lot of different factors have been found to underlie safety culture, the most commonly measured factors are regarded as safety policies, safety rules and procedures, incentives, training, communication, workers' involvement, safety managers' commitment, and employees' safety behavior. Likewise, the dependence relations among these dimensions constitute the hypotheses of the study.

Even though traditional measures of safety performance rely primarily on some form of accident or injury data, safety-related behaviors such as safety compliance and safety participation can also be considered as components of safety performance. Safety compliance represents the behavior of the employees in ways that increase their personal safety and health. Safety participation represents the behavior of employees in ways that increase the safety and health of co-workers and that support an organization's stated goals and objectives [14].

In the current study, we conceptualized employee safety performance as a bidimensional, facet-specific aspect of job performance. In accordance with Griffin and Neal [15], we suggest that employee safety performance can be operationalized as two types of safety behaviors: safety compliance and safety participation. In this study, safety compliance refers to behaviors focused on meeting minimum safety standards at work, such as following safety procedures and wearing required protective equipment. Safety participation refers to behaviors that support workplace safety, such as helping coworkers with safety-related issues or voluntarily attending safety meetings. As such, safety compliance and safety participation parallel two types of general work performance: task performance and contextual performance, respectively [16].

The Algerian petrochemical industry represented by the group Sonatrach plays an important role in the current global economic environment. Its safety performance is thus of great importance. From 2004 to 2006, this sector was the field of several accidents of which GL1ka and Nezla 19b classified among the major accidents of the world petroleum industry.

These accidents revealed grave weaknesses in the prevention plans in place. This incited business managers to introduce changes in the management system Health, Safety, and the Environment (HSE) and a new policy HSE was organized in 2006.

Recognizing the pivotal effect of safety culture on safety outcomes such as injuries, fatalities, and other incidents, the purpose of this research is to realize a comparative study of safety culture assessment in two petrochemical plants of Sonatrach (which present differences in terms of cross-cultural and accident rates), to identify main indicators for safety culture, and analyze the possible relations between them, and then to produce specific recommendations for the direction of Sonatrach as the way of realizing a sustainable improvement of successful HSE.

The two companies in question are SH/DP/HRM and SH/BP/STATOIL. SH/DP/HRM is the Company of Sonatrach DP Hassi R' Mel, is situated 525 km south of Algiers, the field spreads out over more than 3500 km2, and it is one of the biggest gas fields in the world scale. SH/BP/STATOIL, is the In Amenas gas field located in the eastern central region of Algeria, operated in partnership between Algerian state oil company, Sonatrach, British Petroleum (BP), and Statoil (a Norwegian firm).

SH/BP/STATOIL (Company A) is composed of Algerian-European staff, whereas SH/DP/HRM (Company B) has a purely Algerian human component. Both companies are almost the same size, with a staff of approximately 3000 employees.

2. Materials and methods

The final version of the safety culture survey comprised 41 items. Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from (5) strongly agree to (1) strongly disagree. Minitab 16 software (Pennsylvania State University) was used in this study, along with various tests including descriptive statistical analysis, correlations, factor analysis, and reliability analysis.

Based on an extensive literature review, it was hypothesized that a positive safety culture perceived by employees (i.e., a high score of management commitment, policies, rules and procedures, incentives, training, communication, workers' involvement, etc.) would result in better safety performance (i.e., a high score of employees' perceptions about their safety compliance and safety participation).

The survey was distributed to 1000 randomly selected employees of two national state oil companies in Algeria. A plain language letter accompanied the survey, highlighting the aims of the study and encouraging employees to express their true feelings. In total, 508 responses were received and valid, representing a high valid response rate of 51%. Of these responses, 300 (60%) had been employed in Company A, and 208 (42%) had been employed in Company B. The data collection was completed in approximately 12 months. The study period was from September 2011 to September 2012. Details about the two companies that were studied are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of company and response rate

| Company | Activity sector | Main products | Questionnaire survey details |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Given | Returned, % | Response, % | |||

| Company A | Petrochemical industry SH/BP/STATOIL |

Petroleum products-refining | 500 | 300 | 60 |

| Company B | Petrochemical industry SH/DP/HRM |

Petroleum products-refining | 500 | 208 | 42 |

| Total | 1,000 | 508 | 51 | ||

The only difference between the two companies is intercultural. Company A (SH/BP/STATOIL) is a partnership between Sonatrach, a Britanique oil company and a Norwegian oil company, whereas Company B (SH/DP/HRM) is a subsidiary of Sonatrach.

The production characteristics at the two companies were to some extent comparable. Demographics are also comparable as shown in Table 2. Most of the respondents are men; the mean age and mean experience are also very close in both companies.

Table 2.

Participants at both measurements

| N | Age (y) | SD | Seniority | SD | Male (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company A | 300 | 36.1 | 9.8 | 12.2 | 7.3 | 97.9 |

| Company B | 208 | 37.6 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 9.4 | 98.8 |

SD, standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Factor analysis and reliability

Factor analysis was used to define the underlying structure of the data set. A series of questions was asked about several aspects that were thought to be related to the topic of interest. The variables based on the strongest relationships or highest intercorrelations were grouped together and then named. The 41 items were subjected to a factor analysis with principal component extraction. The initial factor solution was identified by the decision rule that eigenvalues should be greater than or equal to 1.

Furthermore, in any summation of factor scores, these loadings may be used to weigh individual items. Each factor can be thought of as a measurement scale for that particular feature. The analysis was conducted on responses to these items to determine that factor structure. With all 41 items in this survey, the obtained Cronbach α was 0.95, indicating that it was good and appropriate to apply the factor analytic technique to these data sets. According to the results of the Bartlett test of sphericity and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) tests, there were significant interitem correlations and a sufficient sample size related to the number of items in the research questionnaire as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

KMO and Bartlett tests for sampling adequacy

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.974 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett test of sphericity | Approx. Chi-square | 1.144E4 |

| Df | 820 | |

| p | < 0.001 | |

Df, degrees of freedom.

In safety culture dimension, 33 items assessed perceptions of safety management practices. A subsequent analysis yielded an eight-factor solution. The factors were named safety policies, safety rules and procedures, incentives, training, communication, workers' involvement, safety managers' attitude, and behavior.

The reliability coefficient of the safety management practices dimension was 0.941. Eight items assessed safety performance, including factors of employees' safety compliance and safety participation. The reliability coefficient for these factors was 0.923.

Table 4 displays the factors, items, and each variable's factor loading and reliability alpha. The factor loading is derived from a regression analysis and reflects the extent to which an item contributes to its factor. If the loading is high, the item is more typical of the overall meaning of the factor. It is useful to think of the loading as a form of correlation between the single item and the aggregate effect of all the items. All factors contained at least three items and the internal consistency across items in each factor (alpha) was high for all factors.

Table 4.

Results of the factor analysis showing name of each factor, the internal consistency between items for each factor (alpha) and the factor loadings for each item

| Safety management practices (alpha = 0.941) Safety policy (alpha = 0.764) |

Loading |

|---|---|

| Firm coordinates its health and safety policies with other policies to ensure commitment and well-being of workers. | 0.603 |

| Safety policy contains commitment to continuous improvement, attempting to improve objectives already achieved. | 0.585 |

| Written declaration is available to all workers reflecting management's concern for safety, principles of action and objectives to achieve. | 0.548 |

| In my company safe conduct is considered as a positive factor for job promotions. | 0.525 |

| Safety rules and procedures (alpha = 0.856) | |

| The safety procedures and practices in this organization are useful and effective. | 0.689 |

| Safety inspections are carried out regularly. | 0.644 |

| The safety rules and procedures followed in my company are sufficient to prevent incidents occurring. | 0.624 |

| My supervisors and managers always try to enforce safe working procedures. | 0.602 |

| Employees' incentives (alpha = 0.813) | |

| Frequent use of teams made up of workers from different parts of organization to resolve specific problems relating to working conditions. | 0.704 |

| Meetings periodically held between managers and workers to take decisions affecting organization of work. | 0.699 |

| Incentives frequently offered to workers to put in practice principles and procedures of action (e.g., correct use of protective equipment). | 0.673 |

| Resolutions frequently adopted that originated from consultations with or suggestions from workers. | 0.640 |

| Training (alpha = 0.764) | |

| Worker given sufficient training period when entering firm, changing jobs, or using new technique. | 0.704 |

| Instruction manuals or work procedures elaborated to aid in preventive action. | 0.641 |

| Training actions continuous and periodic, integrated in formally established training plan. | 0.627 |

| Training plan decided jointly with workers or their representatives. | 0.618 |

| Management encourages the workers to attend safety training programs. | 0.593 |

| Communication (alpha = 0.818) | |

| There is a fluent communication embodied in periodic and frequent meetings, campaigns, or oral presentations to transmit principles and rules of action. | 0.715 |

| Information systems made available to affected workers prior to modifications and changes in production processes, job positions, or expected investments. | 0.710 |

| Written circulars elaborated and meetings organized to inform workers about risks associated with their work and how to prevent accidents. | 0.665 |

| Workers' involvement (alpha = 0.628) | |

| Management always welcomes opinion from employees before making final decisions on safety related matters. | 0.645 |

| Management consults with employees regularly about workplace health and safety issues. | 0.632 |

| My company has safety committees consisting of representatives of management and employees. | 0.546 |

| Management promotes employees involvement in safety related matters. | 0.515 |

| Safety managers' attitudes (alpha = 0.760) | |

| Managers consider that employees' participation, commitment, and involvement is fundamental to health and safety activities in order to reduce the work accident rate. | 0.762 |

| Managers consider that it is fundamental to monitor activities in order to maintain and improve safety activities. | 0.668 |

| Managers consider training of employees is essential for achieving a safe workplace. | 0.622 |

| Managers consider internal communication is essential to understand and implement safety policy. | 0.557 |

| Safety managers' behavior (alpha = 0.721) | |

| Firm managers take responsibility for health and safety as well as quality and productivity. | 0.618 |

| Managers actively and visibly lead in safety matters. | 0.603 |

| Managers regularly visit workplace to check work conditions or to communicate with employees. | 0.603 |

| Managers encourage meetings with employees and directors to discuss safety matters. | 0.585 |

| Safety is a work requirement and a condition of contracting. | 0.519 |

| Safety performance (alpha = 0.923) Safety compliance (alpha = 0.852) | |

| I use all necessary safety equipment to do my job. | 0.758 |

| I ensure the highest levels of safety when I carry out my job. | 0.713 |

| I carry out my work in a safe manner. | 0.698 |

| I follow correct safety rules and procedures while carrying out my job. | 0.684 |

| Safety participation (alpha = 0.898) | |

| I encourage my co-workers to work safely. | 0.738 |

| I voluntarily carryout tasks or activities that help to improve workplace safety. | 0.737 |

| I put extra effort to improve the safety of the workplace. | 0.729 |

| I always point out to the management if any safety related matters are noticed in my company. | 0.688 |

3.2. Factors scores

Performance scores for the two Algerian state oil companies, on each of the 10 factors for safety culture, were determined by calculating the mean of the participants' responses to the items in each scale. This study was particularly interested in the different cultures between two companies. Therefore, an examination of differences between different respondents was also made. Means for each factor scale are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results for the 10 factors examined for the two oil companies involved in the study

| Company A |

Company B |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| SP | 3.978 | .8435 | 3.298 | .8985 | 3.699 | .9281 |

| SR | 3.884 | .9165 | 3.060 | 1.0111 | 3.546 | 1.0379 |

| EI | 4.200 | .5264 | 2.734 | .7067 | 3.599 | .9422 |

| TR | 4.244 | .5488 | 2.824 | .6994 | 3.663 | .9308 |

| CO | 3.978 | .6542 | 2.572 | .9879 | 3.402 | 1.0631 |

| WI | 3.791 | .5389 | 2.629 | .7951 | 3.315 | .8697 |

| MA | 3.741 | .6445 | 2.537 | .6703 | 3.248 | .8831 |

| MB | 3.961 | .4831 | 2.461 | .7145 | 3.347 | .9439 |

| SC | 4.248 | .5833 | 2.857 | 1.0990 | 3.678 | 1.0783 |

| SPar | 3.712 | .6148 | 2.627 | 1.1188 | 3.268 | 1.0095 |

CO, safety communication; EI, safety incentives; MA, safety manager's attitude; MB, safety manager’s behavior; SC, safety compliance; SP, safety policy; SPar, safety participation; SR, safety rules and procedures; TR, safety training; WI, safety worker’s involvement.

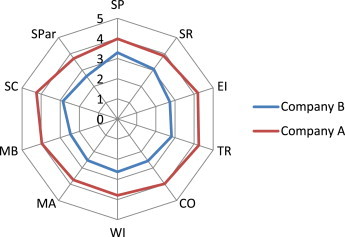

Five hundred and eight employees took part in this study, and the results of the safety culture survey of two oil companies were represented on a radar plot graph (Fig. 1). Each of the factors represented on the radar plot was scored on a standardized scale (5-point scale).

Fig. 1.

Safety culture profile of Company A (SH/BP/STATOIL), Company B (SH/DP/HRM). SP (safety policy), SR (safety rules and procedures), EI (safety incentives), TR (safety training), CO (safety communication), WI (safety worker's involvement), MA (safety manager's attitude), MB (safety manager's behavior), SC (safety compliance), SPar (safety participation).

Company B showed significantly lower evaluations than Company A in terms of safety management practices and safety performance.

Responses on the factors of employees' incentives, safety training and compliance received a very high score (mean = 4.2) from 300 employees of Company A. Means of factors to these data analysis show that respondents perceive safety incentives, safety training, and safety compliance as the most important factors, indicating that the means of motivations are actual and satisfactory, that the plans and periods of trainings are also adequate and sufficient, and furthermore, the respect for rules and procedures is essential for their safety at work.

Responses on the factors of employees' incentives, safety training, and compliance received a very high score (mean = 4.2) from 300 employees of Company A. Means of factors to these data analysis show that respondents perceive safety incentives, safety training, and safety compliance as the most important factors, indicating that the means of motivations are actual and satisfactory, that the plans and periods of trainings are also adequate and sufficient, and furthermore, the respect for rules and procedures is essential for their safety at work.

The mean score ranged from (3.7 to 3.98) of the safety policy, safety rules and procedures, communication, workers' involvement, attitude and behavior of managers, safety compliance and participation of employees in company A are very important and it consider them the key factors of safety performance.

The most important result of the factors analyzed is the role of receiving training in safety management. It is found to predict safety motivation and safety compliance. Management needs to provide the highest level of priority to safety training to convince employees of the need for safety performance.

The mean score (2.67) of the ten factors studied was below the midpoint of 3 in Company B. Most employees in this company, held a negative opinion in regard to safety management practices and safety performance only; the factor of the safety policy, safety rules, and procedures just exceeded 3. This can be explained by the fact that Company B has not exceeded this phase of restructuring, implementation of new rules and procedures, and new HSE policy; the safety culture in Company B did not reach necessary maturity. The commitment of the leadership of Sonatrach on Health and Safety at Work has not come to fruition in Company B. In other words, the haste and commitment of the direction of Sonatrach regarding safety has not yet provided deliberate benefits.

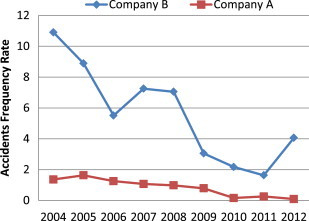

Furthermore, the results show that Company A has a safety culture more developed than that of Company B and has the best safety outcomes in reducing accident rates. Indeed, this was confirmed by several studies [15,17–21]. Fig. 2 clearly shows that accident ratesc of Company A are very low and in continuous decline compared with those of Company B.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of the occupational accidents rates of Company A (SH/BP/STATOIL), Company B (SH/DP/HRM).

The managers of Company A, as already mentioned, are English and Norwegian; consequently, they distinguish themselves by their safety culture maturity. Therefore, these managers, by their positive commitment and by the implementation of adequate means and of safety management practices, were able to improve the safety performance of Company A regarding safety behavior of the Algerian workers and the accident rates.

3.3. Factors correlation

All the safety management practices scores have significant positive correlations with safety compliance and safety participation. The findings confirm the usefulness of safety culture factors as predictors of safety behavior and agree with the literature reporting that organizational and cultural factors affect safety workplace behavior [22,23].

Table 6 shows the intercorrelations of the ten variables of safety management practices with the safety performance variables. The correlation matrix shows that the variable most highly correlated with the safety performance variables safety incentives (SC-EI 0.719, SC-TR 0.717 and SPar-EI 0.647, SPar-TR 0.658); followed by safety manager's behavior (SC-MB 0.678, SPar-MB 0.6.22); safety worker's involvement (SC-WI, 0.671, SPar-WI 0.622); safety manager's attitude (SC-MA 0.624, SPar-MA 0.610); safety communication (SC-CO 0.635, SPar-CO 0.587); safety policy (SC-SP 0.596, SPar-SP 0.618); and safety rules and procedures (SC-SR 0.580, SPar-SR 0.568). Furthermore, the correlations are strong between safety training (TR), safety incentives (EI; 0.785), and between safety manager's commitment (MA and MB), safety incentives (EI), safety training (TR), safety communication (CO), and safety employee's involvement (WI) and between safety compliance and safety participation.

Table 6.

Correlations among all measures in the study

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SP | |||||||||

| 2. SR | 0.637* | ||||||||

| 3. EI | 0.612* | 0.638* | |||||||

| 4. TR | 0.619* | 0.659* | 0.785* | ||||||

| 5. CO | 0.480* | 0.543* | 0.645* | 0.695* | |||||

| 6. WI | 0.544* | 0.567* | 0.695* | 0.701* | 0.754* | ||||

| 7. MA | 0.550* | 0.597* | 0.709* | 0.750* | 0.730* | 0.737* | |||

| 8. MB | 0.485* | 0.528* | 0.752* | 0.750* | 0.755* | 0.779* | 0.766 | ||

| 9. SC | 0.596* | 0.580* | 0.719* | 0.717* | 0.635* | 0.671* | 0.624* | 0.678* | |

| 10. SPar | 0.618* | 0.568* | 0.647* | 0.658* | 0.587* | 0.622* | 0.610* | 0.622* | 0.794* |

*p < 0.01.

SP (safety policy), SR (safety rules and procedures), EI (safety incentives), TR (safety training), CO (safety communication), WI (safety worker's involvement), MA (safety manager's attitude), MB (safety manager's behavior), SC (safety compliance), SPar (safety participation).

In this study, four factors (safety behavior, safety manager's commitment, safety incentives, safety training) were found to be important factors in safety culture in this industry. Therefore, to further promote safety culture, the managers could focus their efforts on these factors.

4. Discussion

This study confirms the definition of the safety culture concept, which identifies the manager's commitment, the employees' involvement, and the safety management system as key indicators. Furthermore, the study shows the important role of the safety culture in the determination of the safety performance in the workplace. Also, we note that the commitment of managers regarding safety plays a fundamental role in the determination of the employees safety behavior, and consequently in occupational accident rates. This is confirmed in the study by Zohar [20], who indicates that the companies that have the lowest percentage of occupational accidents are the ones where the high-level managers are personally involved in a routine way to improve the safety climate within their company.

According to Fernández-Muñiz et al [12], our study shows that the managers' commitment is expressed by attitude and behavior, by showing a continuous interest for the working conditions of their employees, and by getting personally involved in the activities of santé et sécurité au travail (SST) and by the implementation of best safety practices. In other words, the company has to define a safety policy that reflects the principles and the values of the organization in favor of the SST; to establish clear safety rules and procedures; owes implied the workers in SST activities by necessary motivations; supply employees with in-service training so that they can work with safety measures in place; and inform the workers about the risks to which they are exposed and the correct way to dispute them. Therefore, the workers become aware of the importance of SST, so that they respect the regulations and the procedures of SST, participate actively in the meetings, and offer suggestions to improve the SST.

Our findings support that a safety culture that supports the SST is associated with fewer accidents compared with organizations that did not pay particular attention to safety culture, as shown in the studies of Hofmann and Stetzer [24] and Neal et al [25]. This study, according to Neal and Griffin [26], suggests that the workers who commit to the safety practices realize better performance in reducing occupational accident rates.

Finally, the comparison between two petrochemical plants of the group Sonatrach confirms these results, where the managers of Company A, who are English and Norwegian, distinguish themselves by the maturity of their safety culture, have significantly higher evaluations than Company B in terms of safety management practices and safety performance.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Accident occurred on January 19th, 2004 at the level of the complex of liquefaction of the industrial park of Skikda - Algeria. It caused 27 deaths, 80 wounded persons, and three units of liquefaction.

Accident of the well Nezla 19 Gassi Touil (Hassi Messaoud) occurred on September 15th, 2006. There were nine victims, borers of the Entreprise Nationale des Travaux aux Puits (ENTP) among whom two are reported missing and the loss of the device of drilling of a 4 million dollar cost.

Accidents Rate (TF) = Accident number with stop × 1000.000/number of hours work.

References

- 1.Von Thaden T.L., Wiegmann D.A., Mitchell A.A., Sharma G., Zhang H. 2003. Safety culture in a regional airline: results from a commercial aviation safety survey. Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology, OH, Dayton, Ohio, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper M.D. Towards a model of safety culture. Safety Sci. 2000;36:111–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guldenmund F.W. The nature of safety culture: a review of theory and research. Safety Sci. 2000;34:215–257. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilpert B. The relevance of safety culture for nuclear power operations. In: Wilpert B., Itoigawa N., editors. Safety Culture in Nuclear Power Plant. Taylor & Francis; London: 2001. pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll J.S. Safety culture as an ongoing process: culture surveys as opportunities for enquiry and change. Work Stress. 1998;12:272–284. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox S., Cox T. The structure of employee attitudes to safety: a European example. Work Stress. 1991;5:93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox S., Flin R. Safety culture: philosopher's stone or man of straw? Work Stress. 1998;12:189–201. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Vol. 75. INSAG-1; Vienna: 1986. Summary report on the Post Accident review meeting on the Chernobyl Accident, Safety Ser. p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pidgeon N.F. Safety culture and risk management in organizations. J Cross-Cultural Psychol. 1991;22:129–140. Review Meeting on the Chernobyl Accident. (IAEA Safety Series Report INSAG-1) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper M.D. Wiley J; Chichester UK: 1998. Improving safety culture: a practical guide; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACSNI Human Factors Study Group . HMSO; London: 1993. Third report: organising for safety, advisory committee on the safety of nuclear installations. Health and Safety Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Muñiz B., Montes-Peón J.M., Vázquez-Ordás C.J. Safety culture: analysis of the causal relationships between its key dimensions. J Safety Res. 2007;38:627–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefranc G., Guarnieri F., Rallo J.M., Garbolino E., Textoris R. PSAM11 & ESREL; Helsinki, Finland: 2012. Does the management of regulatory compliance and occupational risk have an impact on safety culture? [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagan P.E., Montgomery J.F., O'Reilly J.T. 12th ed. National Safety Council; Illinois, USA, Chicago (IL): 2001. Accident prevention manual for business and industry. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin M.A., Neal A. Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, 2000 safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:347–358. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borman W.C., Motowidlo S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: the meaning for personnel selection research. Hum Perform. 1997;10:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper M.D., Philips R.A. Exploratory analysis of the safety climate and safety behavior relationship. J Safety Res. 2004;35:497–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dedobbeleer N., Beland F. A safety climate measure for construction sites. J Safety Res. 1991;22:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siu O., Phillips D.R., Leung T. Safety climate and safety performance among construction workers in Hong Kong: the role of psychological strains as mediators. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36:359–366. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zohar D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: theoretical and applied implications. J Appl Psychol. 1980;65:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zohar D. A group-level model of safety climate: testing the effect of group climate on micro accidents in manufacturing jobs. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85:587–596. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baram M., Schoebel M. Safety culture and behavioral change at the workplace. Safety Sci. 2007;45:631–636. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinodkumar M.N., Bhasi M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation, 2010 mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:2082–2093. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann D.A., Stetzer A. A cross-level investigation of factors influencing unsafe behaviors and accidents personnel. Psychology. 1996;49:307–339. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neal A., Griffin M.A., Hart P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Safety Sci. 2000;34:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neal A., Griffin M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:946–953. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]