Abstract

Objective

To examine if economic development in China correlates with physical growth among Chinese children and adolescents.

Methods

The height, body weight and physical activity level of children and adolescents aged 18 years and under, as well as dietary data, were obtained from seven large surveys conducted in China between 1975 and 2010. Chinese economic development indicators were obtained from the World Bank. Trends in body weight, height, economic data and diet were examined. Tests were conducted to check for correlations between height at 17 years of age and three indicators of economic development: gross domestic product, urbanization and infant mortality rate. Regional differences in physical growth were assessed.

Findings

Between 1975 and 2010, the growth of children and adolescents improved in tandem with economic development. The largest increment in height was observed during the period of puberty. Regional inequalities in nutritional status were correlated with disparities in economic development among regions. Over the past two decades, undernutrition declined among children less than 5 years of age, but in 2010 underweight and stunting were still common in poor rural areas. A large increase in obesity was observed in both urban and rural areas, but especially in large cities and, more recently, in small and medium-sized cities and affluent rural areas.

Conclusion

The average weight of children and adolescents has been increasing progressively since the 1970s. Current strategies to combat both child undernutrition and obesity need to be improved, especially in poor rural areas.

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner si le développement économique en Chine est corrélé avec la croissance physique chez les enfants et adolescents chinois.

Méthodes

La taille, le poids et le niveau d'activité physique des enfants et adolescents âgés de 18 ans et moins, ainsi que les données relatives à leur alimentation, ont été obtenus à partir de 7 grandes études menées en Chine entre 1975 et 2010. Les indicateurs du développement économique chinois ont été obtenus auprès de la Banque mondiale. Les tendances en matière de taille, de poids, des données économiques et de l'alimentation ont été examinées. Des tests ont été effectués pour vérifier les corrélations entre la taille à l'âge à 17 ans et 3 indicateurs du développement économique: le produit national brut, le taux d'urbanisation et le taux de mortalité infantile. Les différences régionales en matière de croissance physique ont été analysées.

Résultats

Entre 1975 et 2010, la croissance des enfants s'est améliorée en tandem avec le développement économique. La plus grande augmentation de taille a été observée pendant la puberté. Les inégalités régionales en matière d'alimentation ont été corrélées avec les disparités du développement économique existant entre les régions. Au cours des 2 dernières décennies, la dénutrition a diminué chez les enfants de moins de 5 ans, mais en 2010, les insuffisances pondérales et les retards de croissance étaient toujours courants dans les zones rurales pauvres. Une forte augmentation de l'obésité a été observée à la fois dans les zones urbaines et rurales, mais particulièrement dans les grandes villes et, plus récemment, dans les villes de petite et moyenne taille et dans les zones rurales riches.

Conclusion

Le poids moyen des enfants et adolescents a augmenté progressivement depuis les années 1970. Les stratégies actuelles de lutte contre la dénutrition et l'obésité chez les enfants doivent être améliorées, en particulier dans les zones rurales pauvres.

Resumen

Objetivo

Examinar si el desarrollo económico de China está relacionado con el crecimiento físico entre los niños y adolescentes chinos.

Métodos

Se obtuvieron datos sobre la altura, el peso y el nivel de actividad física de niños y adolescentes hasta 18 años, así como datos sobre la dieta, a partir de siete grandes encuestas llevadas a cabo en China entre 1975 y 2010. Los indicadores del desarrollo económico chino se obtuvieron del Banco Mundial. Se examinaron las tendencias en el peso corporal, la altura, los datos económicos y la dieta. Se realizaron pruebas para comprobar la correlación entre la altura a los 17 años de edad y tres indicadores del desarrollo económico: el producto interior bruto, la urbanización y la tasa de mortalidad infantil, y se evaluaron las diferencias regionales en el crecimiento físico.

Resultados

Entre 1975 y 2010, el crecimiento de los niños mejoró a la par que el desarrollo económico. El mayor incremento en la altura se observó durante la pubertad. Las desigualdades regionales en el estado nutricional se correlacionaron con las diferencias de desarrollo económico entre las regiones. En las últimas dos décadas, la desnutrición disminuyó entre los niños menores de cinco años, pero, en 2010, una talla y peso bajos seguían siendo frecuentes en zonas rurales pobres. Se observó un gran aumento de la obesidad tanto en zonas urbanas como rurales, pero especialmente en las grandes ciudades y, más recientemente, en ciudades pequeñas y medianas y en zonas rurales prósperas.

Conclusión

El peso medio de los niños y adolescentes ha ido aumentando progresivamente desde la década de 1970. Es necesario mejorar las estrategias actuales para combatir tanto la desnutrición como la obesidad infantil, particularmente, en las zonas rurales pobres.

ملخص

الغرض

دراسة ما إذا كانت التنمية الاقتصادية في الصين ترتبط بالنمو البدني بين الأطفال والمراهقين في الصين.

الطريقة

تم الحصول على طول الأطفال والمراهقين في سن 18 سنة فأقل وأوزان أجسامهم ومستوى نشاطهم البدني، بالإضافة إلى بيانات النظام الغذائي، من سبع دراسات استقصائية كبرى تم إجراؤها في الصين في الفترة بين عامي 1975 و2010. وتم الحصول على مؤشرات التنمية الاقتصادية في الصين من البنك الدولي. وتم دراسة الاتجاهات في وزن الجسم والطول والبيانات الاقتصادية والنظام الغذائي. وأجريت الاختبارات للكشف عن الارتباطات بين الطول في سن 17 عاماً ومؤشرات التنمية الاقتصادية الثلاثة: الناتج المحلي الإجمالي والتوسع العمراني ومعدل وفيات الرضع. وتم تقييم الاختلافات في النمو البدني بين الأقاليم.

النتائج

تحسن نمو الأطفال بين عامي 1975 و2010 بالترادف مع التنمية الاقتصادية. ولوحظت أقصى زيادة في الطول خلال فترة البلوغ. وارتبطت التباينات في الحالة التغذوية بين الأقاليم بالفوارق في التنمية الاقتصادية بين الأقاليم. وعلى مدار العقدين المنصرمين، انخفض نقص التغذية بين الأطفال الأقل من خمسة سنوات ولكن في عام 2010 ظل نقص الوزن والتقزم شائعين في المناطق الريفية الفقيرة. ولوحظت زيادة كبيرة في السمنة في المناطق الحضرية والريفية على حد سواء، وبالأخص في المدن الكبيرة، وفي الآونة الأخيرة لوحظت في المدن الصغيرة ومتوسطة الحجم والمناطق الريفية الغنية.

الاستنتاج

يزداد متوسط وزن الأطفال والمراهقين تدريجياً منذ سبعينيات القرن العشرين. ويجب تحسين الاستراتيجيات الراهنة لمكافحة نقص التغذية والسمنة لدى الأطفال، لا سيما في المناطق الريفية الفقيرة.

摘要

目的

调查中国的经济发展是否与中国儿童和青少年体格发育有关联。

方法

从1975到2010年在中国开展的七个大型调查中获取18岁及以下儿童和青少年的身高、体重和身体活动水平以及饮食数据。从世界银行获取中国经济发展指标。调查体重、身高、经济数据和饮食的趋势。执行检验以检查17岁青少年身高和三项经济发展指标(国内生产总值、城市化和婴儿死亡率)之间的相关性。评估体格发育的地区差异。

结果

1975至2010年间,儿童发育随经济发展同步改善。据观察,青春期身高增长最大。地区营养状态不均衡与各个地区经济发展差异有关。在过去二十年中,五岁以下孩子营养不良状况减少,但是在2010年,贫穷农村地区依然普遍存在体重不足和生长迟缓的现象。城市和农村地区都出现大幅增加的肥胖儿童,但在大城市尤其如此,这种情况最近在中小城市和富裕的农村地区也凸显出来。

结论

自二十世纪七十年代以来,儿童和青少年的平均体重逐步增加。必须改进当前应对儿童营养不良和肥胖症的策略,在贫穷乡村地区尤其如此。

Резюме

Цель

Определить, коррелирует ли экономическое развитие в Китае с физическим ростом китайских детей и подростков.

Методы

Рост, вес тела и уровень физической активности детей и подростков в возрасте до 18 лет, а также данные по питанию были получены из семи крупных исследований, проведенных в Китае в период с 1975 по 2010 гг. Показатели экономического развития Китая были получены от Всемирного банка. В ходе исследования были рассмотрены изменения показателей массы тела, роста, экономических данных, а также режим питания. Были проведены исследования корреляции роста детей в возрасте 17 лет с тремя показателями экономического развития: валовым внутренним продуктом, уровнем урбанизации и младенческой смертностью. Проведена оценка региональных различий в физическом развитии.

Результаты

В период с 1975 по 2010 гг. рост детей улучшался в соответствии с экономическим развитием. Самый интенсивный рост наблюдался в период полового созревания. Региональные неравенства в уровне питания коррелировали с различиями в экономическом развитии регионов. За последние два десятилетия уровень недостаточного питания снизился среди детей в возрасте до пяти лет, но в 2010 году дефицит массы тела и задержка в росте все еще были широко распространены в бедных сельских районах. Значительное увеличение числа людей, имеющих ожирение, наблюдалось как в городских, так и в сельских районах, но особенно в крупных городах, а в последнее время в малых и средних городах и богатых сельских районах.

Вывод

Начиная с 1970-х годов постепенно увеличивается средний вес детей и подростков. Необходимо совершенствование используемых стратегий по борьбе как с детским недоеданием, так и ожирением, особенно в бедных сельских районах.

Introduction

In 1978, the Government of China introduced economic reforms to convert the country’s planned economy into a free-market system. Since then, sustained economic productivity has greatly increased the food supply, average household income and personal expenditure on food.1,2 With increasing urbanization, the average Chinese diet has become higher in fat and calories, and lower in dietary fibre.3 Also, the level of physical activity during work and leisure time has declined.4 In short, dietary changes after these economic reforms have been accompanied by a rise in diseases related to affluence.5,6

Child-growth assessments are useful not only for monitoring a population’s nutritional status, but also for gauging inequalities in human development among different populations.7 Although many growth and nutrition surveys among children and adolescents have been carried out in China,8,9 few have tried to link trends in child growth and nutrition to changes in economic development. One study that evaluated the effects of China’s economic reforms on the growth of children showed an increase in the average height of children in both rural and urban areas. However, the increase in urban areas was five times that of rural areas.10

Since the economic reforms, income inequalities have increased between western rural areas and coastal areas, as well as between and within rural and urban areas.11 These inequalities have probably influenced the regional distribution of malnutrition and how this distribution has changed over time.12

The objective of this paper is to give an overall picture of long-term trends in the growth and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents by examining the results of seven large surveys conducted over the past 35 years. We focused on regional disparities in child and adolescent growth and nutritional status, as well as on changes in the pattern and rates of malnutrition after the transition to a more high-fat, high-energy-density and low-fibre diet in an attempt to determine if these changes were associated with the country’s economic development.

Methods

Data procurement

Growth and nutrition data

Data on the growth and nutritional status of children and adolescents between 0 and 18 years of age were extracted from published data and raw datasets of seven large surveys undertaken in one or more areas with different economic characteristics in China between 1975 and 2010. The following surveys were included: National Growth Survey of Children under 7 years in the Nine Cities of China; National Growth Survey for Rural Children under 7 years in the Ten Provinces of China; National Epidemiological Survey on Simple Obesity in Childhood; Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health; China National Nutrition Survey; Chinese Food and Nutrition Surveillance system and China Health and Nutrition Survey. A summary of these surveys can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the nationwide surveys of child and adolescent growth and nutrition used to obtain data for studying child growth, China, 1975–2010.

| Survey | Purpose of survey | Time of survey | Area | Age (years) | Data measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Growth Survey of Children under 7 years in the Nine Cities of China, 201113 | To establish standards for child growth and development | 1975, 1985, 1995 and 2005 | Cities of Beijing, Xi’an, Harbin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Fuzhou and Kunming and the surrounding rural areas | 0–7 | Height, weight, body mass index |

| National Growth Survey for Rural Children under 7 years in the Ten Provinces of China, 201114 | To measure the growth and development of children in rural areas | 1985 and 2006 | Rural areas of ten provinces of Jilin, Shanxi, Gansu, Xinjiang, Jiangsu, Sichuan, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangxi and Guizhou | 0–7 | Height, weight |

| National Epidemiological Survey on Simple Obesity in Childhood, 201215 | To examine the epidemiological distribution of obesity and its risk factors | 1986, 1996 and 2006 | Urban areas of Beijing, Xi’an, Harbin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Fuzhou and Kunming | 0–7 | Obesity; risk factors |

| Chinese National Survey on Students Constitution and Health, 201216–19 | To assess the nutritional and health status of schoolchildren | 1985, 1991, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2005 and 2010 | 30 of the 31 mainland provinces of China (excluding Xizang) | 6–22 | Height, weight, body mass index; age of sperm production and menarche; overweight and obesity; 50 m, 50 m × 8 shuttle, 1000 m run time |

| China National Nutrition Survey,a 201120 | To assess nutritional status, diet and health | 1982, 1992 and 2002 | The 31 mainland provinces of China | 0–18, 19–75 | Undernutrition (including “stunted overweight”), over-nutrition; calories and protein intake |

| Chinese Food and Nutrition Surveillance System, 201121–23 | To monitor nutritional status and diet among poor and non-poor children in rural areas | 1990, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2005 and 2010 | Seven provinces/municipalities of Hebei, Heilongjiang, Ningxia, Guangdong, Sichuan, Beijing | 0–5 | Underweight, wasting, stunting; “stunted and overweight” |

| China Health and Nutrition Survey,a 201224–26 | To monitor the diet and nutritional status of Chinese residents | 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006 and 2009 | Provinces of Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi and Guizhou | 0–18, 19–75 | General and abdominal obesity; energy, fat, carbohydrate and protein intake; sedentary behaviours |

Classification of economic areas was based on five indices: regional gross domestic product (GDP), total yearly income per capita, average food consumption per capita, natural growth rate of population, and the regional social welfare index.8 The areas were categorized from highest to lowest economic status as large coastal cities, high, medium or low cities, high, medium or low rural areas and poor western rural areas.

Economic data

Development indicators for China were obtained from the World Bank;29 GDP per capita, the Gini index and the percentage of the population living in urban areas between 1970 and 2012.

Mortality data

Mortality rates for infants and for children less than 5 years of age between 1990 and 2013 were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease study.30

Dietary data

Dietary data for children and adolescents – daily intake of calories, fats, and protein – were obtained from the China Health and Nutrition Survey24 and the China National Nutrition Survey.20

Sedentary behaviour and physical activity

To describe trends in the level of physical activity, data on sedentary behaviour (hours per day watching television or videos or using the computer) and on passive commuting to and from school were obtained from replies to the China Health and Nutrition Survey questionnaire.25,26

Data analysis

Since the study designs, location and demographic characteristics of the population vary among the surveys, data from subsequent rounds of the same survey were used to assess trends. We assessed undernutrition using data for underweight and stunting. Underweight was defined as less than minus two standard deviations from the median weight-for-age of the reference population. Stunting was defined as less than minus two standard deviations from median height-for-age of the reference population. We assessed obesity using data for both overweight and obesity as defined by the Working Group on Obesity in China, adjusted for each year of age.31

We examined the statistical associations between physical growth and economic development using ecological comparisons and trends. To explore the relationship between height and GDP and urbanization and infant and child mortality rates, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r), adjusting for sex. Trends in the prevalence of underweight, stunting, overweight and obesity were assessed using the χ2 test. SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, United States of America) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Secular trends in growth

Between 1975 and 2010, the average height of children and adolescents increased steadily, without any tendency to plateau. The largest increment was noted around puberty, particularly among males, e.g. an increase of 11.9 cm in 13-year-old urban boys. The difference in height between the sexes at 18 years of age increased from 10.3 cm to 12.3 cm during this same period.

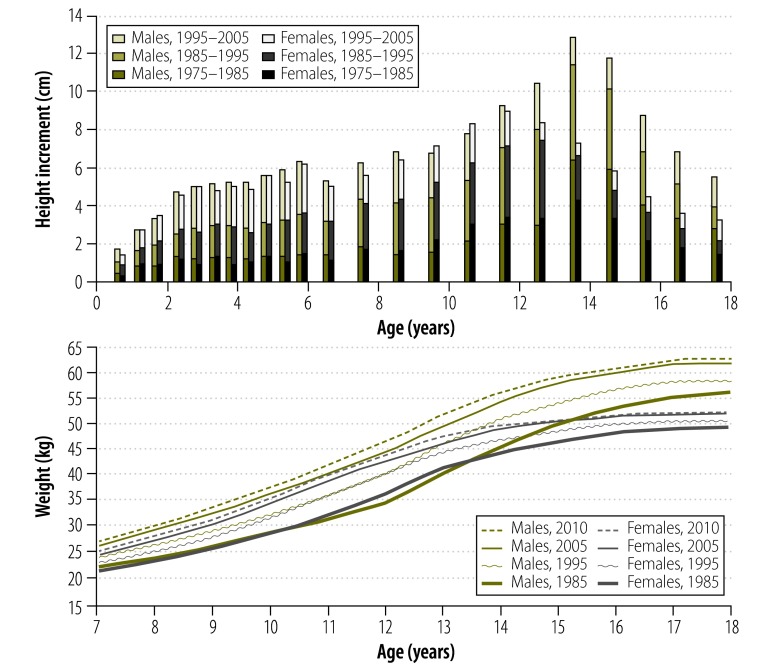

Body weight increased in both sexes and all age groups from 1985–2010. After 2005, in all age categories boys were heavier than girls (Fig. 1). To assess whether the increase in adolescents’ average height was associated with economic development – as captured by urbanization, GDP per capita and the Gini index – (Fig. 2), we looked for correlations between two of these indicators and the average height of adolescents 17–18 years of age.

Fig. 1.

Changes in physical height and body weight of children and adolescents living in Chinese urban areas, 1975–2010

Sample size: n = 140 229 aged 0–18 years in 1975; n = 79 194 for children less than 7 years of age in 1985; n = 79 154 for children less than 7 years of age in 1995; n = 69 760 for children less than 7 years of age in 2005; n = 204 973 aged 7–18 years in 1985; n = 105 409 aged 7–18 years in 1995; n = 117 997 aged 7–18 years in 2005 and n = 107 574 aged 7–18 years in 2010.

Data sources: National Growth Survey of Children under 7 years in the Nine Cities of China13 and Chinese National Survey on Students Constitution and Health.32

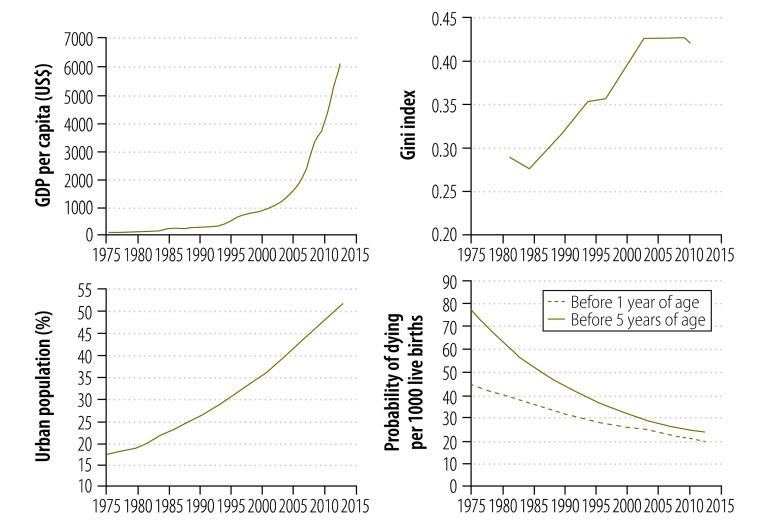

Fig. 2.

Trends in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, Gini index, urban population and child mortality rate in China, 1975–2010

US$, United States dollars.

Data sources: GDP, Gini index and urban population from the World Bank;29 infant mortality and under-5 years mortality rates from the World population prospects: the 2010 revision.30

Height showed a close correlation with GDP per capita (r = 0.90, P < 0.0001) and with urbanization (r = 0.92, P < 0.0001). We also looked for a correlation between the decline in infant and under-5 mortality rates (Fig. 2) and average height and observed that they were both negatively correlated (r = −0.95; P < 0.0001), even after sex adjustment (r = −0.94; P < 0.0001).

Geographical disparities

Differences in height were observed in areas having different economic characteristics. Data from the National Growth Survey of Children under 7 years in Nine Cities of China and the National Growth Survey for Rural Children under 7 years in Ten Provinces of China showed that, on average, children of both sexes in rural areas were 2.1 cm (standard deviation, SD: 1.2) shorter than those in suburban areas and 3.6 cm (SD: 2.0) shorter than those in urban areas.

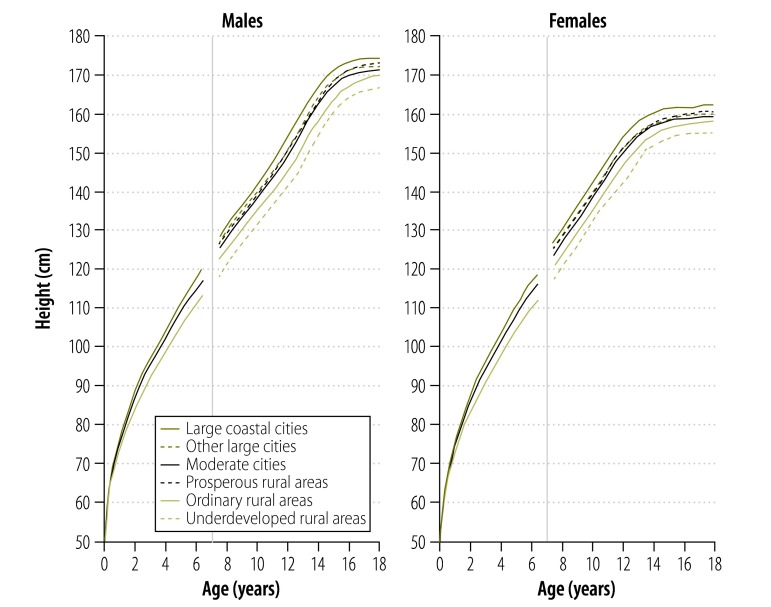

According to the Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health, children and adolescents between 7 and 18 years of age who lived in a coastal city were taller, on average, than those living in other provincial capitals. They were also markedly taller, on average, than those living in medium-sized or small cities. Similar differences were observed among rural areas showing high, moderate and poor economic development (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Physical heighta in children and adolescents of different economic status groups, China, 2005

a Height was measured as length for children less than 3 years of age.

Sample size: n = 69 760 urban children less than 7 years of age; n = 69 015 suburban children less than 7 years of age; n = 95 925 rural children less than 7 years of age; n = 81 438 urban children and adolescents aged 7–18 years; n = 111 584 rural children and adolescents aged 7–18 years.

Data sources: National Growth Survey of Children under 7 years in the Nine Cities of China,13 National Growth Survey for Rural Children under 7 years in the Ten Provinces of China9 and Chinese National Survey on Students Constitution and Health.17,18

Trends in malnutrition

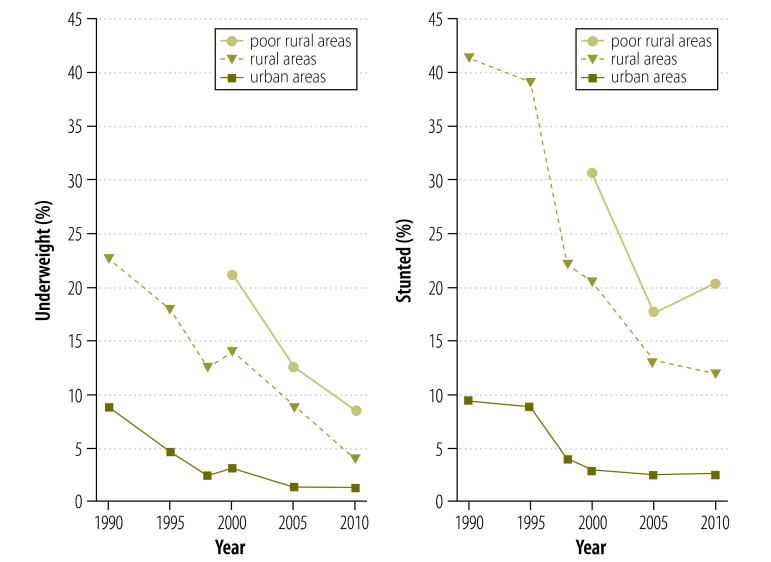

The prevalence of undernutrition in children less than 5 years of age was highest in poor rural areas. Compared with the 1990s, the overall prevalence of undernutrition has declined sharply – by 74% for underweight and 70% for stunting. Significant downward trends in the prevalence of both underweight and stunting were observed for all areas (P < 0.001). However, in poor rural areas in 2010, the prevalence of underweight and stunting was still high, at 8.0% and 20.3%, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Trends in underweighta and stuntingb in children less than 5 years of age, China, 1990–2010

a Underweight was defined as below minus two standard deviations from median weight-for-age of the reference population.

b Stunting was defined as below minus two standard deviations from median height-for-age of the reference population.

Sample size: n = 3200 rural children and n = 1130 urban children in 1990; n = 2139 rural children and n = 765 urban children in 1995; n = 10 729 rural children and n = 5770 urban children in 2000; n = 10 501 rural children and n = 5535 urban children in 2005; n = 10 596 rural children and n = 4803 urban children in 2010.

Data source: Chinese Food and Nutrition Surveillance System.21–23

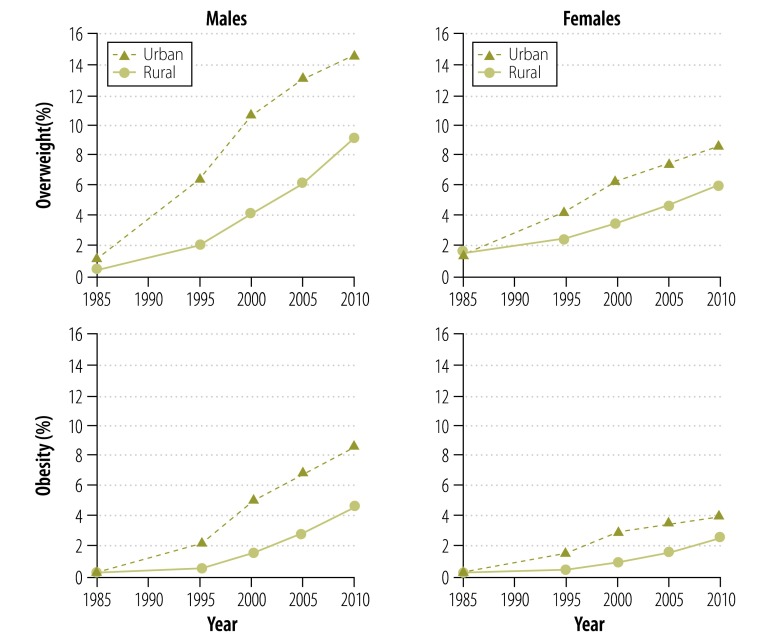

In 2010, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was found to be highest among urban boys (23.2%), followed by rural boys (13.8%), urban girls (12.7%) and rural girls (8.6%). Significant increases were noted in the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity in all groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Between 1985 and 2010, the proportion of obese males increased faster than that of obese females. In urban areas, male obesity increased 0.34 percentage points per year, compared with 0.15 for female obesity. In rural areas, the increase was 0.18 percentage points per year for male obesity, compared with 0.10 for female obesity. The increase in obesity in urban areas between 1985 and 2000 was twice that of the increase in rural areas during the same time period. However, between 2005 and 2010, the annual increase in obesity in rural areas has outpaced that of urban areas (0.34 versus 0.30 percentage points in males and 0.17 versus 0.10 percentage points in females).

Fig. 5.

Trends in overweight and obesitya in children and adolescents, 7–18 years of age, China, 1985–2010

a Overweight and obesity were defined by using the references of the Working Group on Obesity in China. The cut-offs for overweight and obesity were adjusted for each sex–age group.31

Sample size: n = 409 946 in 1985; n = 204 997 in 1995; n = 216 786 in 2000, n = 234 421 in 2005 and n = 215 319 in 2010.

Data source: Chinese National Survey on Students Constitution and Health.16

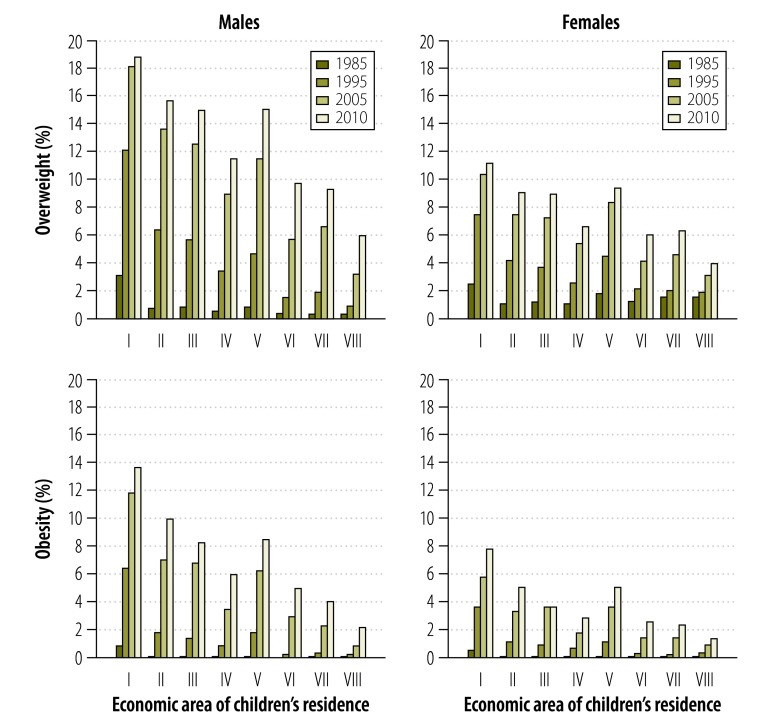

Fig. 6 illustrates the burden of obesity in areas with different economic characteristics. Large coastal cities were the first to exhibit a rise in overweight and obesity and had the largest increase in prevalence – 32.6% (males) and 19.1% (females) in 2010. Similar increases followed in other areas: first in large, prosperous cities, followed by medium-sized cities with a large middle class and, finally, by the more affluent rural areas. Although an increase in obesity was noted between 1985 and 2010 in western rural areas with low economic development, these areas still had the lowest prevalence of obesity in 2010.

Fig. 6.

Changes in overweight and obesea children and adolescents, 7–18 years of age, in areas with different economic characteristicsb, China, 1985–2010

I: large coastal cities; II-IV: other cities in declining order of economic development; V-VII: rural areas in declining order of economic development; VIII: western rural areas.

a Overweight and obesity were defined by using the references of the Working Group on Obesity in China. The cut-offs for overweight and obesity were adjusted for each sex–age group.31

b Areas were categorized from I-VIII on five economic indices: regional gross domestic product, total yearly income per capita, average food consumption per capita, natural growth rate of population, and the regional social welfare index, where large coastal cities (I) have the highest economic status and western rural areas have the lowest economic status (VIII).

Sample size: n = 359 946 in 1985, n = 204 977 in 1995, n = 216 654 in 2005 and n = 297 062 in 2010.

Data source: Chinese National Survey on Students Constitution and Health.19

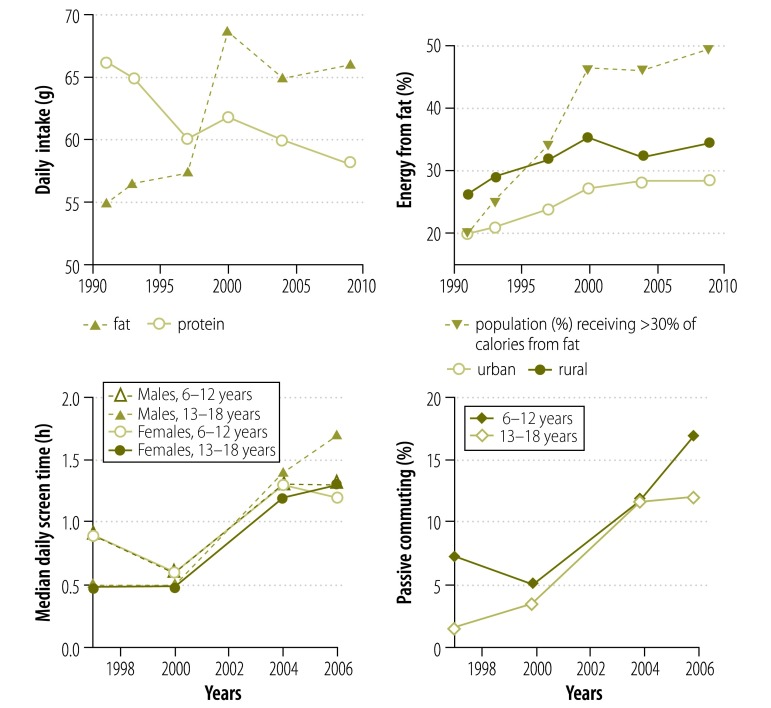

Trends in nutrition and physical activity

To assess whether factors associated with increased body weight in children and adolescents were affected by China’s economic reforms, we obtained data on fat and protein intake and level of physical activity. Between 1991 and 2009, people’s diets in China changed considerably. For children and adolescents between 7 and 17 years of age, the average daily fat intake increased from 55 to 66 g and the average daily protein intake decreased from 66 to 58 g. There was also an increase in fats as a proportion of total caloric intake and an increase in the proportion of children and adolescents obtaining more than 30% of their energy from fat. In addition, during this period time spent in front of a television, video or computer also increased, as did the proportion of children and adolescents who commuted to school in a motorized vehicle (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Changes in dietary intake (1991–2009)a and physical activities (1997–2006)b for children and adolescents, China

a Dietary graphs include children and adolescents aged 7–17 years.

b Screen time includes watching television in 1997 and 2000, and watching television and using computers in 2004 and 2006. Passive commuting is the percentage of school-aged children who commuted to school in a bus.

Sample size: n = 2714 in 1991; n = 2542 in 1993; n = 2516 in 1997; n = 2142 in 2000; n = 341 in 2004; n = 1072 in 2006 and n = 996 in 2009.

Discussion

The economic transition

In the wake of the 1978 reforms, China underwent many changes in its social structures, living conditions and diet. This has been accompanied by a positive trend in the physical growth of children.33 An empirical division of China’s economic development into stages based on the time cycle of China growth surveys facilitates the analysis of its association with trends in children’s growth. In Stage I (before 1975) – out of scope of this analysis – a previous subtle upward trend in growth ceased and even reversed owing to the detrimental effects of famine. In Stage II (1975–1985), children’s growth began to improve again with the recovery of the national economy, and positive trends emerged in older age groups of children in the major cities. In Stage III (1985–1995), physical growth continued to improve in parallel with sustained economic growth. The increment in height among children in rural areas exceeded that seen in children living in urban areas because of improved living standards, health care and increased food supply in the rural areas in the mid-1980s.9 In Stage IV (1995–2005), even higher growth increments were documented among both urban and rural residents. According to data from 2005 to 2010 (Stage V), the increment has continued and does not seem to be levelling off.34

The growth of children in China has improved in recent decades and this improvement is more pronounced at puberty than at earlier or later ages, consistent with other population-based studies.35 The increase in height at the age of 18 years is already present in younger ages and the eventual increase in adult height is established during the first 2 years of life.

In the Netherlands, the secular increase in growth has come to a halt after 150 years, with males now 13.1 cm taller on average than females.36 Since sex difference in adult height widens gradually as secular increases in growth continue, the difference of 12.3 cm between the sexes in 2010 suggests that the positive trend in Chinese children may continue.

Before the economic reforms, food had been in short supply,3 but after 1978, when a policy of liberal food production was introduced and annual economic growth improved, people began to eat more meat and grains and less vegetables. Child growth and nutrition improved and overweight and obesity were still rare. In 1985 and 1986, the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents was below 1% in large cities.15,19

In 1986, China started its first specific survey on obesity and found that the Chinese diet had become richer in fats and calories and lower in fibre, a change that was introducing an increased risk of chronic diseases.37,38 Obesity among infants and preschool children increased by a factor of 2.8 between 1986 and 2006.15 And between 1985 and 2010, overweight among school-aged children and adolescents increased from 1.11% to 9.62% and obesity from 0.13% to 4.95%.16 Additionally, between 1993 and 2009 the prevalence of obesity rose from 6.1% to 13.1% among children between the ages of 6 and 17 years.39 The higher prevalence of overweight males contrasts with the situation in some non-Asian countries.40

In 2012, for the first time in history, China’s urban population outnumbered its rural population.41 This urbanization can be seen as a double-edged sword. Although it has brought increased access to health care and improvements in basic health infrastructure for many, it has also brought about changes in diet and lifestyle, such as an increase in the availability of sweets and fast-food restaurants and in the use of television, personal computers and cars, all of which can pose substantial health risks.42,43

We have shown that in recent decades fat intake and physical inactivity have risen among Chinese children, with a resulting increase in childhood obesity and a documented decline in physical fitness. For instance, the capacity for endurance running among Chinese students declined significantly between 1985 and 2010.32,44

Dual burden of malnutrition

Large discrepancies still exist between rural and urban areas both in health conditions and in health care.45 Decades of observation suggest that despite improved growth in children belonging to all economic groups, a large growth disparity persists between the rural and suburban areas and the urban areas,9 and among different economic subgroups within these areas.17,18

Compared with the late 1980s and early 1990s,46 in 2010, malnutrition in childhood declined dramatically, owing to sustained economic development, sound nutrition policies, improved health services for women and children and broad implementation of child nutritional interventions.23 However, in the same year, nutrition in rural areas was still poor, with a high prevalence of underweight and stunting among children less than5 years of age. Another survey in 2009 reported 15.9% prevalence for stunting, 7.8% for underweight and 3.7% for wasting in poor rural ares.47

We have also observed a paradoxical situation: in 2006, prevalence of overweight children was as high as 16.8%, while that of stunting was 57.6% among the children in the same poor areas of China’s midwestern provinces.48 The coexistence of stunting and overweight in the same child is a result of protein and energy malnutrition, which retards height despite increased body weight,49 and Chinese rural children have a lower daily protein intake than urban children.24

Childhood obesity has become a serious public health problem in China.19,50 The current strategies for preventing and controlling malnutrition need to be re-examined. Research on obesity prevention and control needs to be improved and nutrition policies need to be aligned with appropriate obesity prevention strategies. Cross-sectoral collaboration such as between health and agriculture, needs to be promoted.

Our study has shown that regional inequalities in child growth and nutrition in China accompany regional economic disparities. Therefore, to promote equitable growth for all children in China, strategies for optimal nutrition need to focus more closely on disadvantaged groups in the poor and underdeveloped areas.

Funding:

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81302439).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Chow G. China’s economic transformation. New York (NY): Blackwell Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu ZL, Khan MS. Economic issues 8: why is China’s growth so fast? Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 1997.

- 3.Du S, Lu B, Zhai F, Popkin BM. A new stage of the nutrition transition in China. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A) 1a:169–74 10.1079/PHN2001290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin L, Stolk RP, Corpeleijn E. Motorized transportation, social status, and adiposity: the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):1–10 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell TC, Junshi C, Brun T, Parpia B, Yinsheng Q, Chumming C, et al. China: From diseases of poverty to diseases of affluence: Policy implications of the epidemiological transition. Ecol Food Nutr. 1992;27(2):133–44 10.1080/03670244.1992.9991235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Poel E, O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E. Urbanization and the spread of diseases of affluence in China. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7(2):200–16 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Onis M, Frongillo EA, Blössner M. Is malnutrition declining? An analysis of changes in levels of child malnutrition since 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(10):1222–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji CY, Chen TJ. Secular changes in stature and body mass index for Chinese youth in sixteen major cities, 1950s-2005. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20(5):530–7 10.1002/ajhb.20770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Zong X, Zhang J, Zhu Z. Physical growth of children in urban, suburban and rural mainland China: a study of 20 years change. Biomed Environ Sci. 2011;24(1):1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen T, Habicht JP, Chang Y. Effect of economic reforms on child growth in urban and rural areas of China. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(6):400–6 10.1056/NEJM199608083350606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook IG. Pressures of development on China’s cities and regions. In: Cannon T, editor. China’s economic growth: the impact on regions, migration and the environment. London: Macmillan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones-Smith JC, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, Popkin BM. Cross-national comparisons of time trends in overweight inequality by socioeconomic status among women using repeated cross-sectional surveys from 37 developing countries, 1989–2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):667–75 10.1093/aje/kwq428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zong XN, Li H, Zhu ZH. Secular trends in height and weight for healthy Han children aged 0–7 years in China, 1975–2005. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23(2):209–15 10.1002/ajhb.21105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Shi J, Himes JH, Du Y, Yang S, Shi S, et al. Undernutrition status of children under 5 years in Chinese rural areas - data from the National Rural Children Growth Standard Survey, 2006. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(4):584–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zong XN, Li H. Secular trends in prevalence and risk factors of obesity in infants and preschool children in 9 Chinese cities, 1986–2006. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46942. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Cai CH, Wang HJ, Dong B, Song Y, Hu PJ, et al. [The trend analysis of overweight and obesity in Chinese students during 1985–2010]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;46(9):776–80 Chinese [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji CY, Zhang X. Comparison of physical growth increments among Chinese urban student populations during 1985-2005. Chin J Sch Health. 2011;32:1164-7 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji CY, Yin XJ. Comparison of increments on physical growth among Chinese rural student populations during 1985-2005. Chin J Sch Health. 2011;32:1158-63 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji CY, Chen TJ; Working Group on Obesity in China (WGOC). Empirical changes in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese students from 1985 to 2010 and corresponding preventive strategies. Biomed Environ Sci. 2013;26(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Wedick NM, Lai J, He Y, Hu X, Liu A, et al. Lack of dietary diversity and dyslipidaemia among stunted overweight children: the 2002 China National Nutrition and Health Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(5):896–903 10.1017/S1368980010002971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, He W, Wang Y, Deng L, Jia F. Nutritional status of children during and post-global economic crisis in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2011;24(4):321–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang S, He W, Chen CM. [The growth characteristics of children under 5 in the past 15 years]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2006;35(6):768–71 Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health of China. National report on nutritional status of children aged 0–6 year. 2012. Available from: http://www.doc88.com/p-0823981115058.html [cited 2014 April 14].

- 24.Cui Z, Dibley MJ. Trends in dietary energy, fat, carbohydrate and protein intake in Chinese children and adolescents from 1991 to 2009. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(7):1292–9 10.1017/S0007114511006891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui Z, Bauman A, Dibley MJ. Temporal trends and correlates of passive commuting to and from school in children from 9 provinces in China. Prev Med. 2011;52(6):423–7 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui Z, Hardy LL, Dibley MJ, Bauman A. Temporal trends and recent correlates in sedentary behaviours in Chinese children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):93. 10.1186/1479-5868-8-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhai FY. Follow-up study on dietary structure and nutrition status change in Chinese residents. Beijing: Science Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CM. Ten-year tracking nutritional status in China, 1990–2000. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.World development indicators. [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank. Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/variableSelection/selectvariables.aspx?source=world-development-indicators [cited 2013 Dec 3].

- 30.World population prospects: the 2010 revision, volume 1: comprehensive tables. New York (NY): United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji CY; Working Group on Obesity in China. Report on childhood obesity in China (1)–body mass index reference for screening overweight and obesity in Chinese school-age children. Biomed Environ Sci. 2005;18(6):390–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji CY; Study Group on Chinese Students Physical Fitness and Health. [Report on the physical fitness and health surveillance of Chinese school students]. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2007. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji CY, Chen TJ. Secular changes in stature and body mass index for Chinese youth in sixteen major cities, 1950s–2005. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20(5):530–7 10.1002/ajhb.20770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen TJ, Ji CY. Secular change in stature of urban Chinese children and adolescents, 1985–2010. Biomed Environ Sci. 2013;26(1):13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole TJ. Secular trends in growth. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(2):317–24 10.1017/S0029665100000355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schönbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, Buitendijk SE, HiraSing RA, et al. The world’s tallest nation has stopped growing taller: the height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009. Pediatr Res. 2013;73(3):371–7 10.1038/pr.2012.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell TC, Campbell TM 2nd. The China study: the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and the startling implications for diet, weight loss, and long-term health. Dallas (TX): BenBella Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du S, Lü B, Wang Z, Zhai F. [Transition of dietary pattern in China]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2001;30(4):221–5 Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang YJ, Xi B, Song AQ, Liu JX, Mi J. Trends in general and abdominal obesity among Chinese children and adolescents 1993–2009. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(5):355–64 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00066.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cattaneo A, Monasta L, Stamatakis E, Lioret S, Castetbon K, Frenken F, et al. Overweight and obesity in infants and pre-school children in the European Union: a review of existing data. Obes Rev. 2010;11(5):389–98 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong P, Liang S, Carlton EJ, Jiang Q, Wu J, Wang L, et al. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):843–52 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61878-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng TO. Fast food, automobiles, television and obesity epidemic in Chinese children. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98(1):173–4 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, van der Lans I, Dagevos H. Impacts of fast food and the food retail environment on overweight and obesity in China: a multilevel latent class cluster approach. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(1):88–96 10.1017/S1368980011002047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma J; Study Group on Chinese Students Physical Fitness and Health. [Report on the physical fitness and health surveillance of Chinese school students.] Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2012. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–42 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang Y, Zhai F, Li W, Ge K, Jin D, de Onis M. Nutritional status of preschool children in poor rural areas of China. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(1):105–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu D, Liu A, Yu W, Zhang B, Zhang J, Jia F, et al. [Status of malnutrition and its influencing factors in children under 5 years of age in poor areas of China in 2009]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2011;40(6):714–8 Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Höjer B, Guo S, Luo S, Zhou W, Wang Y. Stunting and ‘overweight’ in the WHO Child Growth Standards – malnutrition among children in a poor area of China. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):1991–8 10.1017/S1368980009990796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popkin BM, Richards MK, Montiero CA. Stunting is associated with overweight in children of four nations that are undergoing the nutrition transition. J Nutr. 1996;126(12):3009–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lobstein T. China joins the fatter nations. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5(5):362–4 10.3109/17477166.2010.510563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]