Abstract

Background and Objective:

Mycobacterium tuberculosis has developed resistance to antituberculosis drugs and becoming a major and alarming public health problem in worldwide. This study was aimed to determine antituberculosis drug resistance rate and to identify multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in West of Iran.

Materials and Methods:

Of 130 samples were included between December 2011 and July 2012 in the study from that 112 cases were M. tuberculosis. The proportional method was carried out according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on Lowenstein-Jensen against isoniazid, rifampicin, streptomycin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, para aminosalicylic acid, ethionamide, cycloserine (CYC). The microdilution method was carried out using 7H9 broth with 96 well-plates.

Results:

From 112 isolates, resistance was observed to isoniazid 18 (16.07%), rifampicin 16 (14.28%), streptomycin 25 (22.32%), ethambutol 15 (13.39%), pyrazinamide 27 (24.10%), para aminosalicylic acid 19 (16.96%), CYC 4 (3.57%), and ethionamide 14 (12.5%) cases. 16 isolates were MDR.

Conclusion:

The high prevalence of MDR-TB in our study is assumed to be due to recent transmission of drug-resistant strains. Overall, the rate of drug resistance in our study was high, which is in line with findings of some high-burden countries. Hence that early case detection, rapid drug susceptibility testing, and effective anti-TB treatment is necessary.

Keywords: Drug-resistant, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MDR

INTRODUCTION

In the scope of a remarkable improvement in the life expectancy of the people of the world, along with the introduction of chemotherapeutic measures, tuberculosis (TB) prevalence witnessed a significant decline in the second half of the twentieth century. However, escalating HIV infection as well as negligence in TB control have caused an increase in TB incidence over the last decade, in both developing and developed countries[1,2] Moreover, several other factors such as homelessness, poverty, lack of infrastructure in public health and inadequate access to health services have played an important role in worsening the situation.[3] TB is an important health problem in Iran and the issue has become even more so as a result of increasing drug-resistant strains; drug resistance complicates efforts to control TB. Moreover, the problem of extensively drug-resistant strains has recently been introduced.

Culture-based techniques on solid media for susceptibility testing take almost 4 weeks to give results, so that there is a need for rapid determination of the drug susceptibility for Mycobacterium tuberculosis,[4] so liquid culture, enable laboratories to determine Mycobacterium susceptibility to first-line drugs within 1-2 weeks incubation time.[5]

This study was aimed to determine anti-tuberculosis drug resistance rate and to identify multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in West of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted from December 2011 to July 2012. The samples that collected from patients, was performed by using the Ziehl-Neelsen method. Smear-positive samples were culture on Lowenstein-Jensen medium. The identification of M. tuberculosis complex strains was based on conventional methods such as niacin, nitrate reduction, catalase 68, and pigment production.[5]

Drug susceptibility testing (DST) against isoniazid (0.2 μg/mL), Rifampcin (40.0 μg/mL), streptomycin (4.0 μg/mL), ethambutol (2.0 μg/mL) and pyrazinamide (900 and 1200 μg/mL), para amino salicylic acid (PAS), ethionamide (ET), cycloserine (CYC) were performed by the proportional method on Löwenstein-Jensen media. Drug resistance was defined as >1% growth in the presence of 0.1 μg of antibiotic per milliliter.[6]

For microdilution method, isoniazid, rifampicin, Streptomycin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, para aminosalicylics acid, ET and CYC from Sigma-Aldrich were used. Solutions were prepared sterile water, except for rifampicin, which was diluted in the HCL. Test was performed in 96-well plates. Dilutions of each drug were prepared in the test wells in complete 7H9 broth, the final drug concentrations being: Isoniazid 0.2 μg/mL, rifampicin 1 μg/mL, streptomycin 2 μg/mL and ethambutol 5 μg/mL, pyrazinamide 100 μg/mL, Para aminosalicylic acid 2 μg/mL, ET μg/mL 5 and CYC 30 μg/mL.[7] 5 μL of each bacterial suspension was added to 95 μL of drug-containing culture medium. Control wells were prepared with culture medium only and bacterial suspension only. The plates were sealed and incubated for 2 weeks days at 37°C.[7]

RESULTS

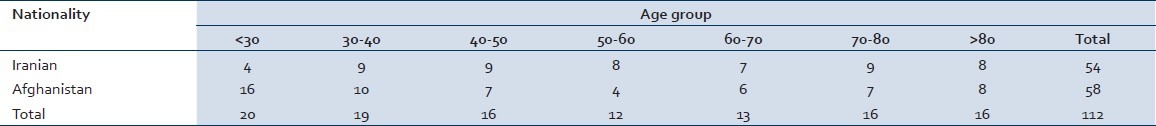

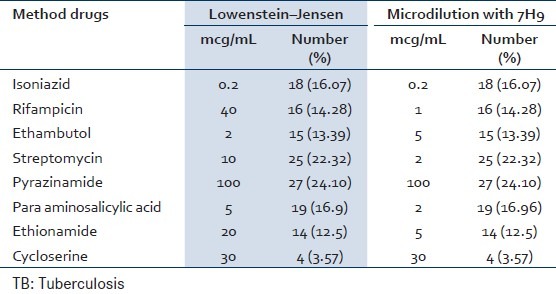

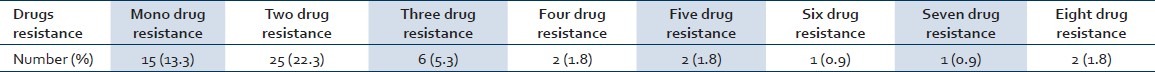

During the period of the month between December 2011 and July 2012, a total of 130 patients were included in the study from that 112 cases were M. tuberculosis and detection of antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using the proportional and microdilution methods. Of the total patients, 54 cases were Iranian and 58 cases were Afghanistan [Table 1] and also 64 cases (57.1%) were male and 48 cases (42.9%) were female. In this study, resistance was detected with two method that Showed the same results [Table 2], the results of this approach are: Isoniazid 18 (16.07%), rifampicin 16 (14.28%), streptomycin 25 (22.32%), ethambutol 15 (13.39%), pyrazinamide 27 (24.10%), para aminosalicylic acid 19 (16.96%), CYC 4 (3.57%) and ethionamide 14 (12.5%) cases. Resistance to one drug (single drug resistance), isoniazid resistance 1 case (0.89%), streptomycin resistance 7 cases (6.25%), ethambutol resistant 1 case (0.89%), pyrazinamide resistant 3 cases (2.67%), para aminosalicylic acid resistance (0.89%), ethionamide resistance (1.78%) was seen. Mono resistance to isoniazid, ethambutol and para aminosalicylic included 1 case and for streptomycin, pyrazinamide, para aminosalicylic acid and ethionamide were observed in 1, 7, 3, and 2 cases, respectively [Table 3]. In 18 cases, isoniazid resistance was combined with resistance to two or more drugs. 16 isolates were MDR (at least isoniazid and rifampicin).

Table 1.

Distribution of age-national patients

Table 2.

Anti-TB test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with microdilution and culture

Table 3.

Drugs resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis is becoming a worldwide problem due to the recurrence of the disease, the appearance of drug-resistant strains and the association of TB with the HIV pandemic.[8] Tuberculosis programs face challenges in reducing MDR-TB. The treatment of MDR-TB tuberculosis is difficult due to side-effects, which is expensive and often unsuccessful.[9] It may take up to 6 weeks to get a phenotypic DST result and during this time many transmission events may take place. In order to prevent the spread of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strategies for the treatment and prevention of MDR Emergency measures are required, so that alternative methods need to be evaluated to improve the speed of diagnosis of drug resistance.[10,11]

In this study, we found that a greater number of males diagnosed with pulmonary. In this study, we found that a greater number of males diagnosed with pulmonary TB than females (64.1% and 47.9%, respectively), this similar the drug resistance was associated with 70.9% males and 29.15% females, in Tanzania.[6] Globally, a 70% predominance of males over female patients was reported.[12] The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 67.2% of the global male population was diagnosed with TB as compared to the female population.[2,13,14]

The higher prevalence of MDR-TB in men over women may be explained by the fact that women are more compliant with treatment and therefore less likely to receive inadequate treatment than men. Furthermore, men are almost always outdoors and therefore more susceptible to community-acquired resistant strains.

In this study, we found that drug resistance to pyrazinamide (24/10%) was the most common, followed by streptomycin (22/32%) and isoniazid (16/07%). The high prevalence of pyrazinamide and streptomycin resistance in our study may be due to widespread use of these antibiotics in the past for treatment of different infectious diseases. This is in agreement with the observations of other Iranian researchers.[14,15] Resistance to isoniazid in this study was 16.1%, and was also higher than that seen in Ethiopia,[15] and in Mozambique (14.9%). In 2008, the WHO reported a worldwide resistance rate to isoniazid of 5.9%.[16,17] According to the WHO, isoniazid resistance rates higher than 10% can predict the development of MDR-TB.[17] In our study, high resistance may be caused by: That isoniazid is a first-line drug or poor compliance by patients.

CONCLUSION

The high level of INH resistance among the study population also is an indicator that this drug will be completely useless; this indicates a high probability for developing MDR-TB in the future. INH is also the drug of choice for chemoprophylaxis of TB and is used in developed countries for treating latent TB.

The high prevalence of MDR-TB in our study is assumed to be due to recent transmission of drug-resistant strains. Overall, the rate of drug resistance in our study was high, which is in line with findings of some high-burden countries.

So that early case detection, rapid DST, effective anti-TB treatment is necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The study was financially supported by the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for grant 88003.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banfi E, Scialino G, Monti-Bragadin C. Development of a microdilution method to evaluate Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:796–800. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shamaei M, Marjani M, Chitsaz E, Kazempour M, Esmaeili M, Farnia P, et al. First-line anti-tuberculosis drug resistance patterns and trends at the national TB referral center in Iran - Eight years of surveillance. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e236–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díaz-Infantes MS, Ruiz-Serrano MJ, Martínez-Sánchez L, Ortega A, Bouza E. Evaluation of the MB/BacT Mycobacterium detection system for susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1988–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1988-1989.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts GD, Goodman NL, Heifets L, Larsh HW, Lindner TH, McClatchy JK, et al. Evaluation of the BACTEC radiometric method for recovery of mycobacteria and drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from acid-fast smear-positive specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:689–96. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.3.689-696.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merza MA, Farnia P, Salih AM, Masjedi MR, Velayati AA. The most predominant spoligopatterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates among Iranian, Afghan-immigrant, Pakistani and Turkish tuberculosis patients: A comparative analysis. Chemotherapy. 2010;56:248–57. doi: 10.1159/000316846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velayati AA, Farnia P, Masjedi MR, Ibrahim TA, Tabarsi P, Haroun RZ, et al. Totally drug-resistant tuberculosis strains: Evidence of adaptation at the cellular level. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:1202–3. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent PT, Kubica GP. A Guide for Level III Laboratory. Vol. 5. Atlanta, CA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1985. pp. 765–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization, 2009. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. Global Tuberculosis Control: Epidemiology, Strategy, Financing: WHO Report 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossau R, Traore H, De Beenhouwer H, Mijs W, Jannes G, De Rijk P, et al. Evaluation of the INNO-LiPA Rif. TB assay, a reverse hybridization assay for the simultaneous detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and its resistance to rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2093–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, Farmer PE, Mishustin SP, Strelis AK, Andreev YG, et al. Treatment of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Tomsk, Russia: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372:1403–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sotgiu G, Ferrara G, Matteelli A, Richardson MD, Centis R, Ruesch-Gerdes S, et al. Epidemiology and clinical management of XDR-TB: A systematic review by TBNET. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:871–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00168008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uplekar MW, Rangan S, Weiss MG, Ogden J, Borgdorff MW, Hudelson P. Attention to gender issues in tuberculosis control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:220–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. The WHO/IUATLD Global Project on Anti-tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Last accessed on 2010 Sep 10]. Antituberculosis Drug Resistance in the World Report No. 4 Prevalence and Trends. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2008/WHO_HTM_TB_2008.394_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassu D, Daniel A, Eshatu L, Mekdes GM, Benium F. Drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from smear negative pulmonary tuberculosis patients, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;22:212–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunes EA, De Capitani EM, Coelho E, Panunto AC, Joaquim OA, Ramos Mde C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial isolates among patients with recent HIV infection in Mozambique. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:822–8. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008001000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abate G, Miörner H. Susceptibility of multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to amoxycillin in combination with clavulanic acid and ethambutol. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:735–40. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization, 2010. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.3. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. Multidrug and Extensively Drug-Resistant TB (M/XDR-TB). 2010 Global Report on Surveillance and Response. [Google Scholar]