Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is a rare but debilitating complication of a variety of pelvic surgical procedures.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We report the case of a 45-year-old female who underwent the STARR (Stapled Trans Anal Rectal Resection) procedure, that was complicated by a 30mm rectovaginal fistula (RVF). We successfully repaired the fistula by trans-perineal approach and pubo-coccygeus muscle interposition. Seven months later we can confirm the complete fistula healing and good patient's quality of life. We carefully describe our technique showing the advantages over alternative suturing, flap reconstruction or resection procedures.

DISCUSSION

This technique is fairly easy to perform and conservative. The pubo-coccygeus muscle is quickly recognizable during the dissection of the recto-vaginal space and the tension-free approximation of this muscle by single sutures represents an easy way of replacement of the recto-vaginal septum.

CONCLUSION

In our experience the use of pubo-coccygeus muscle interposition is an effective technique for rectovaginal space reconstruction and it should be considered as a viable solution for RVF repair.

Abbreviations: RVF, rectovaginal fistula; STARR, stapled trans anal rectal resection; TRANSTAR, transanal stapled resection

Keywords: Rectovaginal fistula repair, STARR, TRANSTAR, Pubo-coccygeus muscle

1. Introduction

Rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is a rare but debilitating complication of a variety of pelvic surgical procedures. The majority of RVFs (nearly 90%) are caused by obstetric injuries, some as a result of perineal tears. Rectovaginal fistula can also occur in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (particularly Crohn's disease), and following gynecological and colorectal surgery. Rectovaginal fistula has been also described as possible complication of vaginoplasty in male-to-female transsexuals during androginoid conversion surgery1–3.

Fistulas deriving from pelvic procedures can be caused by various postoperative complications, primarily direct trauma (perforation) that is not identified or inadequately treated intraoperatively. Secondary fistulas can arise in case of suture insufficiency following treatment of a defect in the context of infection. They may also arise as a result of secondary infection of a hematoma.

In recent years, RVFs has been an increasingly common complication after hemorrhoid or pelvic floor surgery, particularly in cases where staplers or foreign materials were used. While RVFs are an absolute rarity after conventional hemorrhoid surgery, cases of postoperative fistulas have been increasingly reported since the introduction of stapler procedures, with incidences up to 3% in some cases 4–6. Specifically, the focus is drawn toward the more technically challenging STARR (Stapled Trans Anal Rectal Resection) and TRANSTAR (Transanal Stapled Resection) procedures 7–15. Fistulas are usually caused by errors in surgical technique, when the posterior vaginal wall is also caught in the stapler. No statistics are available since the results have primarily been published as case studies 16.

For affected women, the passing of air and secretions or stool from the rectum through the vagina represents a psychosocial burden that, of course, increases with the diameter of the fistula. RVF can result in recurrent infections of the vagina or lower urinary tract.

We describe the case of a 45-year-old female who underwent STARR that was complicated by a 30 mm RVF and required fecal diversion. We repaired the fistula by trans-perineal approach and pubo-coccygeus muscle interposition (levatoroplasty).

2. Presentation of case

A 45 year-old female patient was admitted to our department due to a 30 mm RVF and prolapsing loop colostomy. The patient had undergone STARR procedure for rectal prolapse in a different hospital 1 month before and she had been primarily treated with loop colostomy for fecal diversion. At the time of admission rectal examination demonstrated a persistent large rectovaginal fistula.

3. Surgical technique

The patient is placed in “perineal” position. Surgery begins with a horizontal perineal skin incision drawn directly above the external rectal sphincter (Fig. 1A). The incision is slightly concave downward and must be large enough to allow adequate surgical exposure. After identification of the fistula with a probe, the rectovaginal septum is carefully dissected. The dissection will be carried on upwards along the back wall of the vagina that is grasped with forceps, stretched on the fingers of the surgeon and progressively raised. The rectum is identified below. The exposure can be facilitated by the use of Farabeuf retractors (Fig. 1B). The procedure may be hindered by the post-inflammatory contraction of the tissue that always surrounds the recto-vaginal communication. The rectal wall must be separated from the vagina, taking care not to damage the external rectal sphincter. To prevent tearing of the rectum a finger can be inserted into the rectum in order to better control the rectal wall. The mobilization must be carried on to a level of at least 3 cm above the fistula site. The anterior wall of the rectum must be perfectly exposed before any attempt to suture. The wound edges of the fistula on the rectal side must be excided and the defect closed by interrupted absorbable stitches (Fig. 2A). The same treatment must be reserved to the vaginal side of the fistula (Fig. 2B). The inner edge of the elevators (pubo-coccygeus muscles) is easily identified with the finger by getting down and tensing the external sphincter of the anus. The pubo-coccygeus muscles must be freed upwards and the rectovaginal dissection should be continued laterally. After preparation of the medial aspect of the levator ani muscle, the reconstruction of the rectovaginal space is be performed by approximating on the midline the pubo-coccygeus muscles by 3–4 single absorbable stitches. The levatoroplasty covers the rectal suture and comes between the anterior wall of the rectum and the back wall of the vagina, keeping separate the two suture lines (Fig. 3A). Two Jackson-Pratt drains are then positioned before the closure of the surgical site by absorbable stitches (Fig. 3B).

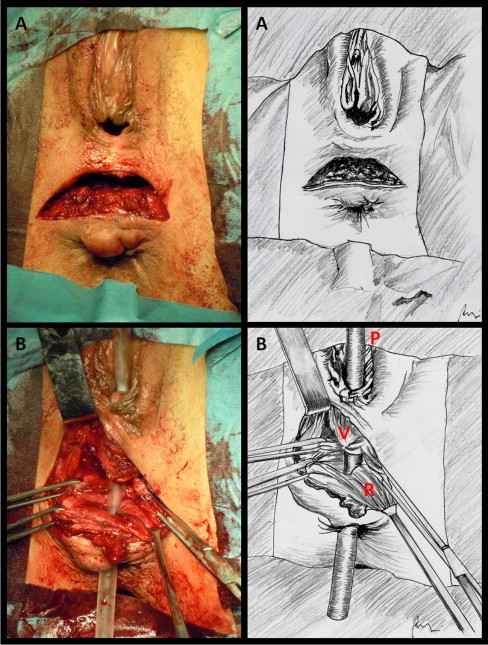

Fig. 1.

(A) Horizontal perineal skin incision drawn directly above the external rectal sphincter. (B) Dissection of the rectovaginal septum. After separation of the back vaginal wall from the anterior aspect of the rectal canal, the RVF is clearly identified by the probe. V, back vaginal wall; R, anterior rectal wall; P, probe inserted into the RVF.

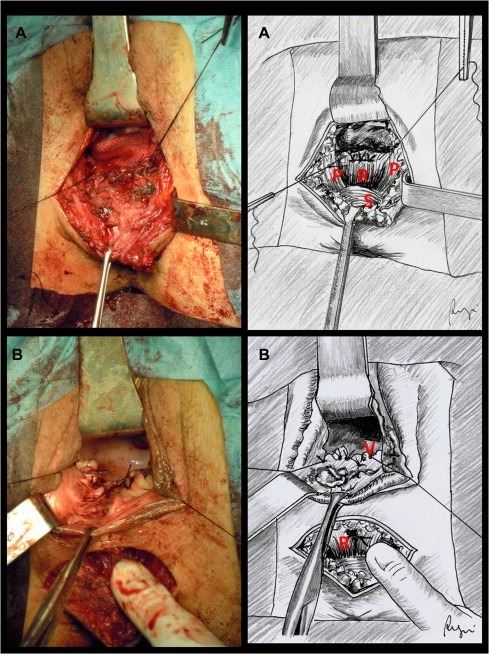

Fig. 2.

(A) Closure of rectal defect by interrupted absorbable stitches (extramucosal single-layer suture). R, anterior rectal wall; S, external rectal sphincter; P, pubo-coccygeus muscles. (B) Closure of vaginal defect by interrupted absorbable stitches after excision of the wound edges of the fistula (extramucosal single-layer suture). V, back vaginal wall; R, rectal wall (repaired).

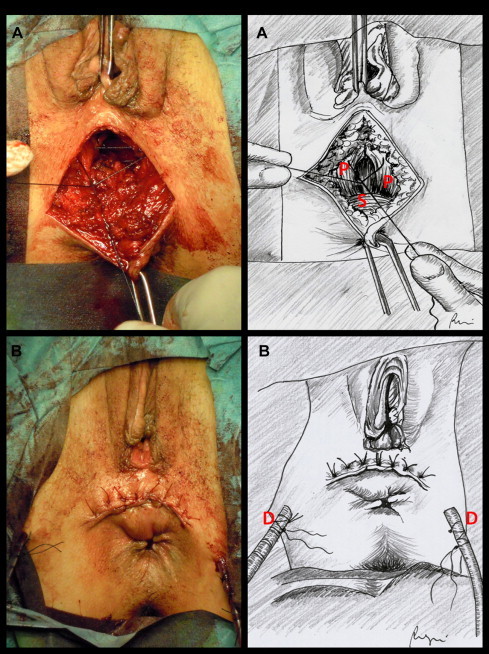

Fig. 3.

(A) Preparation of the medial aspect of the levator ani muscle and reconstruction of the rectovaginal space by approximation of the pubo-coccygeus muscles on the midline. P, pubo-coccygeus muscles; S, external rectal sphincter. (B) Two Jackson-Pratt drains (D) are positioned before the closure of the surgical site by absorbable stitches.

Ultimately the prolapsing loop colostomy was revised and replaced by terminal colostomy.

The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. Three months later, the patient underwent a Gastrografin enema prior to loop colostomy closure. The study showed no rectovaginal fistula. As such the patient underwent colostomy closure and the postoperative course was uneventful. Four months later (7 months after RVF repair) we can confirm the complete fistula healing and good patient's quality of life (included satisfying sexual activity).

4. Discussion

The treatment of RVFs represents a special surgical challenge. In case of RVF following a STARR procedure the repair is further complicated by the high position of the fistula and the presence of a consistent fibrosis in the rectovaginal septum associated to metallic staples. No randomized trials, relevant reviews or guidelines are available on the surgical treatment. Simple fistula suturing, flap reconstruction or resection procedures are all associated with high recurrence rates. All of these procedures share the exclusion of the fistula without reconstruction of the rectovaginal space.

Direct local repair, even with an advancement flap is usually unsuccessful due to inadequate tissue bulk as the anovaginal septum is a thin poorly vascularized structure. Also fecal content is continuously forced to escape through the fistula due to the inherently high pressures of the anorectal region. Hence the interposition of well-vascularized tissue must be considered to separate and protect the vaginal from the rectal sutures, especially in recurrence or large RVFs. This goal can be achieved with an omental flap in combination with fistula closure 17, as well as through the trans-perineal approach. In the latter the reconstruction of the rectovaginal space is performed by a pedicled flap of adipose tissue from the labia majora (Martius procedure) 18, the bulbocavernosus muscle 19, or the gracilis muscle 20,21.

There are very few reports on reconstruction of the anovaginal septum by the interposition of the pubo-coccygeus part of levator ani muscle 22,23. We chose this technique because it is fairly easy to perform and conservative. Moreover our long lasting experience in colo-proctology field prompted us to choose the perineal approach. The pubo-coccygeus muscle is quickly recognizable during the dissection of the recto-vaginal space, as its fibers run longitudinally aside the left and the right side of the vagina and the anal canal. The tension-free approximation of this muscle by single sutures represents an easy way of replacement of the recto-vaginal septum (Fig. 3B). A protective colostomy ultimately provides several advantages within this setting. The reduction in the orthostatic pressure of the stool column as well as a reduction in the local bacterial burden lower the risk of fistula recurrence and promote primary wound healing. We recognize that the time point 1 month after the trauma is questionably early. However we were prompted to early close the recto-vaginal fistula by the physical and psychological sufferance of the patient and the prolapsing loop colostomy.

In conclusion, the use of pubo-coccygeus muscle interposition is an effective technique for rectovaginal space reconstruction and it should be considered as a viable solution for RVF repair.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Funding

The authors declare no sources of funding.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author Contributions

Giacomo Pata, Mario Pasini, Stefano Roncali, Daniela Tognali, Fulvio Ragni have equally contributed to study design and data collection. Giacomo Pata and Fulvio Ragni have contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and to write the paper.

Key learning points

-

•

Postoperative rectovaginal fistulas (RVFs) have been increasingly reported following several surgical procedures.

-

•

For affected women, it represents a psychosocial burden that can result in recurrent infections of the vagina or lower urinary tract.

-

•

The treatment of RVFs represents a special surgical challenge.

-

•

Trans-perineal approach and pubo-coccygeus muscle interposition is an effective technique for rectovaginal space reconstruction.

-

•

It is fairly easy to perform and conservative.

-

•

It should be considered as a viable solution for iatrogenic rectovaginal fistula repair.

References

- 1.Dessy L.A., Mazzocchi M., Corrias F., Ceccarelli S., Marchese C., Scuderi N. The use of cultured autologous oral epithelial cells for vaginoplasty in male-to-female transsexuals: a feasibility, safety, and advantageousness clinical pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:158–161. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000435844.95551.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Revol M., Servant J.M., Banzet P. Surgical treatment of male-to-female transsexuals: a ten-year experience assessment. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2006;51:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perovic S.V., Stanojevic D.S., Djordjevic M.L. Vaginoplasty in male transsexuals using penile skin and a urethral flap. BJU Int. 2000;86:843–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giordano P., Gravante G., Sorge R., Ovens L., Nastro P. Long-term outcomes of stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Surg. 2009;144:266–272. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giordano P., Nastro P., Davies A., Gravante G. Prospective evaluation of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation for stage II and III haemorrhoids: three-year outcomes. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s10151-010-0667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beattie G.C., Loudon M.A. Haemorrhoid surgery revised. Lancet. 2000;355:1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayne D.G., Schwandner O., Stuto A. Defecation syndrome: one-year results of the European STARR registry. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1205–1212. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a9120f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagliardi G., Pescatori M., Altomare D.F., Binda G.A., Bottini C., Dodi G. Results, outcome predictors and complications after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:186–195. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martellucci J., Talento P., Carriero A. Early complications after stapled transanal rectal resection performed using the Contour Transtar device. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1428–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naldini G. Serious unconventional complications of surgery with stapler for haemorrhoidal prolapse and obstructed defaecation because of rectocoele and rectal intussusceptions. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassi R., Rademacher J., Savoia A. Rectovaginal fistula after STARR procedure complicated by haematoma of the posterior vaginal wall: report of a case. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:361–363. doi: 10.1007/s10151-006-0310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuto A., Renzi A., Carriero A., Gabrielli F., Gianfreda V., Villani R.D. Stapled trans-anal rectal resection (STARR) in the surgical treatment of the obstructed defecation syndrome: results of STARR Italian registry. Surg Innov. 2011;18:248–253. doi: 10.1177/1553350610395035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pescatori M., Gagliardi G. Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:7–19. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pescatori M., Dodi G., Salafia C., Zbar A.P. Rectovaginal fistula after double-stapled transanal rectotomy (STARR) for obstructed defaecation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:83–85. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pescatori M., Zbar A.P. Reinterventions after complicated or failed STARR procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ommer A., Herold A., Berg E., Fürst A., Schiedeck T., Sailer M. German S3-guideline: rectovaginal fistula. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2012;10:Doc15. doi: 10.3205/000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schloericke E., Hoffmann M., Zimmermann M., Kraus M., Bouchard R., Roblick U.J. Transperineal omentum flap for the anatomic reconstruction of the rectovaginal space in the therapy of rectovaginal fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2011;14:604–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitel S., Lefevre J.H., Parc Y., Chafai N., Shields C., Tiret E. Martius advancement flap for low rectovaginal fistula: short- and long-term results. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e112–e115. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui L., Chen D., Chen W., Jiang H. Interposition of vital bulbocavernosus graft in the treatment of both simple and recurrent rectovaginal fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1255–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wexner S.D., Ruiz D.E., Genua J., Nogueras J.J., Weiss E.G., Zmora O. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of rectourethral, rectovaginal, and pouch-vaginal fistulas: results in 53 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;248:39–43. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817d077d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zmora O., Tulchinsky H., Gur E., Goldman G., Klausner J.M., Rabau M. Gracilis muscle transposition for fistulas between the rectum and urethra or vagina. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1316–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsang C.B., Madoff R.D., Wong W.D., Rothenberger D.A., Finne C.O., Singer D. Anal sphincter integrity and function influences outcome in rectovaginal fistula repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1141–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF02239436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell T.R., Gallagher D.M. Low rectovaginal fistulas. Approach and treatment. Am J Surg. 1977;34(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]