Abstract

Electronic health records (EHRs) must support primary care clinicians and patients, yet many clinicians remain dissatisfied with their system. This article presents a consensus statement about gaps in current EHR functionality and needed enhancements to support primary care. The Institute of Medicine primary care attributes were used to define needs and meaningful use (MU) objectives to define EHR functionality. Current objectives remain focused on disease rather than the whole person, ignoring factors such as personal risks, behaviors, family structure, and occupational and environmental influences. Primary care needs EHRs to move beyond documentation to interpreting and tracking information over time, as well as patient-partnering activities, support for team-based care, population-management tools that deliver care, and reduced documentation burden. While stage 3 MU's focus on outcomes is laudable, enhanced functionality is still needed, including EHR modifications, expanded use of patient portals, seamless integration with external applications, and advancement of national infrastructure and policies.

Keywords: Primary Care, Electronic Health Records, Meaningful Use

Introduction

The adoption and use of electronic health records (EHRs) holds the promise of improved care and better patient outcomes.1–3 To ensure that all Americans enjoy benefits, national legislation charged the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) with defining national EHR meaningful use (MU) objectives and measures.4 5 Adherence to MU is being reinforced by US$27 billion in incentives.6 7 While MU is intended to encourage clinician use of existing EHR features, it has effectively directed the energies and innovations of EHR vendors as well.8

MU is divided into three stages. Stage 1 focused on promoting data capture and sharing (2011), stage 2 on promoting exchange of health information (2014), and stage 3 on improving outcomes (2016).9–11 Throughout, CMS and ONC have sought input from experts, clinicians, and the public.12

Many have questioned whether EHR design and MU support promising new care models, such as the Accountable Care Organization (ACO) and Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH).13–15 A useful evaluation, which has not been previously made, is how well EHR functionality supports primary care. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) asserts that ‘primary care is the logical foundation of an effective health care system because it can address the large majority of health problems in the population.’16 This is supported by evidence demonstrating that primary care extends life span, reduces morbidity, increases satisfaction, reduces disparities, and is cost effective.17 It is also where the majority of people receive care.18 19

Primary care has embraced EHR adoption and MU. Online appendix A describes the phases of how practices achieve MU. In 2011, 57% of office-based physicians reported using any EHR, and, in 2013, more than half had received MU incentives.20 21 Yet clinicians commonly report EHR dissatisfaction.2,2–25

This article presents a consensus statement from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), and North American Primary Care Research Group. It identifies gaps in current EHR functionality and makes enhancement recommendations to better support primary care. The IOM attributes of primary care were used to define primary care needs, and stage 2 MU eligible provider objectives were used to define EHR functionality. Steps to reach consensus included (1) assigning each MU objective to the primary care attribute it supported,16 26 (2) identifying unmet needs within each attribute, and (3) obtaining iterative input from organization members and 148 practicing clinicians. Initial work was carried out by the 43 members of the NAPCRG Health Information Technology (HIT) working group (primary care HIT leaders from 38 institutions internationally). Practicing clinicians were identified from four practice-based research networks and included family physicians (n=78), internists (n=16), pediatricians (n=18), mid-level providers (n=12), nurses (n=15), and informatics staff (n=9) from 15 states in urban, suburban, and rural communities. Participant consensus was sought during each step.

Primary care attributes

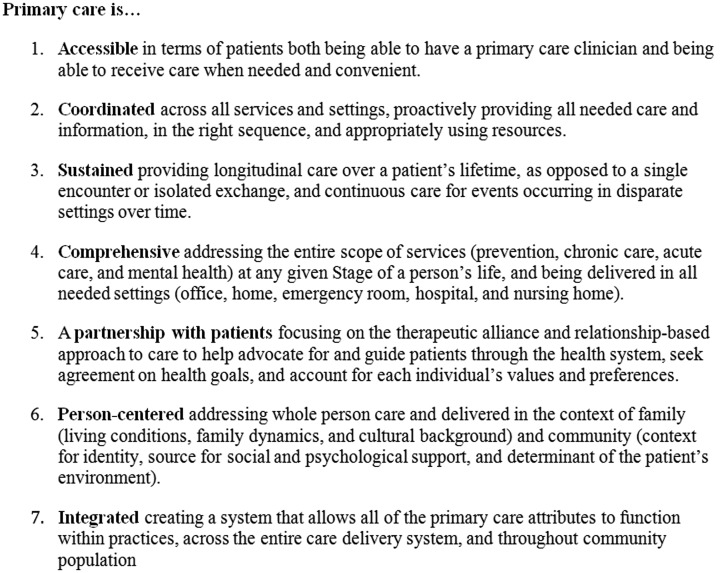

The IOM defines primary care as ‘the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.’16 Central to primary care is the patient–clinician relationship, established with the mutual expectation of continuation over time and predicated on the development of mutual trust, respect, and responsibility. Family and community provide context, and an integrated delivery system provides the means for delivery of care.16 The IOM indentifies seven attributes that characterize primary care (figure 1), 16 which are echoed in the Chronic Care Model, PCMH, and ACO design.27–30 EHRs that meet the needs of primary care will meet the needs of these care models, specialists, and hospital-based clinicians.

Figure 1.

Seven Key Primary Care Attributes Defines by the Institute of Medicine.

MU objectives and primary care attributes

Stage 1 and 2 MU objectives were finalized on July 13, 2010 and August 23, 2012, respectively, and stage 3 will be finalized in 2015.6 31 Two groups of participants are eligible to receive incentives—eligible providers and hospitals. This article focuses on stage 2 provider objectives.

MU objectives are defined by specific reportable measures and targets to achieve.32 Stage 1 has 15 core objectives and 10 additional objectives—five of which clinicians select to report. Stage 2 consists of 17 core and six additional objectives—of which clinicians report three.10 The assignment of each MU objective by the primary care attribute it best supports is presented in table 1. As the MU objectives were not specifically designed around the IOM primary care attributes, some objectives do not clearly support any primary care attribute, and others support multiple primary care attributes. For this perspective, each objective was categorized by group consensus as supporting only one attribute.

Table 1.

Stage 1 and stage 2 meaningful use (MU) objectives categorized by primary care attribute

| MU objectives | Stage 1 objectives | Stage 2 objectives |

|---|---|---|

| IOM primary care attribute: accessibility | ||

| Secure messaging | No measure | Use secure messaging for 10% of patient communications (C) |

| IOM primary care attribute: coordination | ||

| CPOE | Use CPOE for medication orders for 30% of patients (C) | Use CPOE for medication, laboratory results, and radiology orders for 60% of patients, includes drug-formulary check (C) |

| Drug-formulary checks | Implement drug-formulary checks (C) | |

| ePrescribing | Generate and transmit 40% of prescriptions electronically (C) | Generate and transmit 65% of prescriptions electronically (C) |

| Summary of care | Provide patient care summaries for 50% of care transitions (C)* | Provide patient care summaries for 65% of care transitions, includes up-to-date problem, medication, and allergy lists (C) |

| Problem list | Maintain an up-to-date problem list for 80% of patients (C)† | |

| Medication list | Maintain an active medication list for 80% of patients (C)† | |

| Medication allergy list | Maintain an active medication allergy list for 80% of patients (C)† | |

| Timely electronic access to health information | Provide 10% of patients timely electronic access to health information (E) | View, download, and transmit to 3rd party—revised objectives to provide 50% of patients the ability to view, download, and transmit health information electronically (C) |

| Electronic copy of health information | Provide patients with an electronic copy of their health information (C) | |

| Electronic copy of discharge instructions | No measure | |

| IOM primary care attribute: sustained care | ||

| Patient reminders | Send reminders to 20% of patients for follow-up care (E) | Send reminders to 20% of patients for follow-up care (C) |

| Patient list | Generate one list of patients by condition for outreach (E) | Generate one list of patients by condition for outreach (C) |

| IOM primary care attribute: comprehensiveness | ||

| Vital signs | Record vital signs (height, weight, blood pressure, BMI) on 50% patients (C) | Record vital signs (height, weight, blood pressure, BMI) on 50% patients (C) |

| Smoking status | Record 50% of patients’ smoking status (C) | Record 80% of patients’ smoking status (C) |

| Medication reconciliation | Perform medication reconciliation on 50% of patients (E) | Perform medication reconciliation on 65% of patients (C) |

| Laboratory results into EHR | Incorporate 40% of laboratory results as structured data (E) | Incorporate 55% of laboratory results as structured data (C) |

| Imaging results | No measure | 40% of imaging results and information accessible through the EHR (E) |

| IOM primary care attribute: partnership with patients | ||

| Clinical summaries for office visits | Provide patients a clinical summary after 50% of office visits (C) | Provide patients a clinical summary after 50% of office visits (C) |

| Patient-specific education | Identify patient-specific education resources for 10% of patients (E) | Identify patient-specific education resources for 10% of patients (C) |

| Advance directives | Record advanced directives for 50% of patients over 65 years (E) | Record advanced directives for 50% of patients over 65 years(E) |

| IOM primary care attribute: person-centered | ||

| Demographics | Record demographics (language, gender, race, ethnicity, date of birth) on 50% patients (C) | Record demographics (language, gender, race, ethnicity, date of birth) on 80% patients (C) |

| Family history | No measure | Family history (E) |

| IOM primary care attribute: integrated | ||

| CDS | Implement 1 clinical decision support rule (C) | Implement 5 clinical decision support rules counting drug–drug and drug–allergy interactions (C) |

| Drug–drug and drug–allergy interactions | Implement drug–drug and drug–allergy interaction checks (C) | |

| Immunization registry | Be capable of submitting electronic data to immunization registries (E) | Be capable of submitting electronic data to immunization registries (C) |

| Laboratory results to public health agency | Be capable of submitting electronic laboratory results to public health agencies (E) | Be capable of submitting electronic laboratory results to public health agencies (E) |

| Specialized registry | No measure | Be capable of identifying and reporting specific cases to a specialized registry (E) |

| Cancer registry | No measure | Be capable of identifying and reporting cancer cases to a State registry (E) |

| Privacy and security | Protect electronic health information (C) | Protect electronic health information (C) |

*The stage 1 objective is better categorized as ‘partnership with patients’, but the stage 2 modification is categorized as ‘coordinated’.

†The stage 1 objective is better categorized as ‘comprehensive’, but the stage 2 modification is categorized as ‘coordinated’.

BMI, body mass index; C, core (required) MU objective; CDS, clinical decision support; CPOE, computerized physician order entry; E, elective MU objective; EHR, electronic health record; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

Primary care needs and EHR enhancements

As demonstrated in table 1, the content of stage 2 MU objectives appears to inadequately support primary care attributes. MU has driven EHRs to better support the coordinated and integrated attributes, but they do less to promote the accessible, sustained, partnership, and person-centered attributes. For the variety, complexity, and comprehensiveness of primary care to be captured, a fundamental shift is needed from the documentation of episodic and procedural care to the evidence-based personalization of longitudinal whole-person care with active patient and care team participation. Specific EHR enhancements to address unmet primary care needs are outlined in box 1 and in the text below.

Table 2.

Electronic health record (EHR) and information technology enhancements not addressed by meaningful use (MU) and needed to better support primary care

| Primary care attribute: accessibility |

|---|

| Make documenting, accessing, and conveying information non-labor-intensive, to increase time with patients |

| – Accept structured clinical data from existing external sources that can update EHRs |

| – Support EHR use by multiple staff members during clinical encounters for documentation and delivery of care |

| – Allow patients to directly enter health information through patient portals, open notes, and shared EHR space |

| – Do not allow EHRs to achieve MU through additional non-clinically relevant documentation |

| Support enhanced asynchronous care |

| – Allow clinician–patient email, texting, video conferencing, and other bidirectional communication mechanisms |

| – Allow patients to electronically share information they collect (documents, spreadsheets, pictures, device data, etc) |

| Embed tools to assess and monitor clinician accessibility |

| – Create queries for clinicians to track availability |

| – Support mechanisms for patients to electronically schedule appointments |

| – Collect patient reports on a clinician's accessibility |

| Primary care attribute: coordination |

| Expand capacity for EHRs to receive and aggregate information from all settings so primary care clinicians can proactively coordinate care |

| – Provide ‘out of the box’ health information exchange functionality to access all relevant health information |

| – Support timely health information exchanges so clinicians can aggregate information at the point of care |

| – Ensure vendor agnostic standardization of data |

| – Store and exchange all structured data linked to standardized meta-data identifiers |

| – Import discrete data from exchanges into the EHR (not just view data) |

| Provide functionality to help coordinate care among teams internally within offices and externally across organizations and systems |

| – Allow the electronic formation of clinical teams with defined roles for members |

| – Ensure that electronic tasks are distributed on the basis of defined roles |

| – Create tools to track the progress of tasks across team members |

| Track and coordinate ancillary and enabling services (eg, case management, transportation, interpretation, social services, financial assistance) |

| – Provide secure communication with coordination services |

| – Maintain a shared library of local coordination services tailored to the individual |

| – Create and maintain ‘benefits formularies’ delineating coverage of medications, tests, procedures, and services |

| Create a dashboard that synthesizes and prioritizes information about individual, and panels of, patients |

| – Identify and sequence visits with other clinicians, changes in medication and diagnoses, and key results |

| – Identify urgent messages or whether patients have been to an acute care facility or admitted to the hospital |

| Primary care attribute: sustained care |

| Track and support continuity of care |

| – Allow patients to define who they view as their primary care clinician |

| – Allow clinicians to track and limit patient panel size on the basis of number of patients and illness severity61 |

| – Provide tools for practices to measure patient and clinician continuity of care |

| Track and support care over time |

| – Describe chronic conditions and events over time (beginning and end to conditions, changes in severity, and other temporal information) |

| – Update status and severity of chronic conditions based on other information available in the EHR |

| – Allow the documentation and use of health information based on episodes of care |

| – Provide trending tools to show health information as a function of time, influencing data, and events |

| Primary care attribute: comprehensiveness |

| Support the whole spectrum of clinical care |

| – Comprehensively support all aspects of preventive, chronic, acute, and mental health care through documentation, decision support, and outcomes tracking |

| – Support residential, ambulatory, nursing home, emergency, and hospital settings |

| Ensure the accuracy of EHR information |

| – Allow patients to review, correct, and update their health information |

| – Provide a means for clinicians to reconcile differences between patient-reported information, information from health information exchanges, and information in the existing EHR |

| – Build tools to auto-resolve outdated information and identify data inconsistencies |

| Primary care attribute: partnership with patients |

| Incorporate the patient's perspective into EHRs |

| – Document issues that are important to the patient (eg, patient goals, what life activities give meaning, what outcomes would be worse than death) |

| – Allow prioritization of patient goals |

| – Capture and track the patient's presenting complaint and symptoms as well as their evolution over time |

| – Allow patients to enter information into EHRs about their goals, values, beliefs, behaviors, and psychosocial factors |

| Support patient–clinician shared decision-making |

| – Identify who makes decisions, how decisions are made, and available social support |

| – Provide patients with educational material, decision aids, and value-assessment tools tailored to decision needs |

| Primary care attribute: person-centered |

| Support whole-person care50 |

| – Describe and track who the patient is, including social and cultural context, patient narratives, meaningful life events |

| – Expand EHR functionality (eg, documentation, decision support, outcome tracking) beyond disease orientation to include a whole-person perspective |

| Meaningfully record the patient's family history |

| – Cluster family records within EHRs to allow Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA)-compliant cross-referencing and provide family context |

| – Allow patients to record and update family genograms in a simple and intuitive format |

| – Link family history to clinical decision support to identify high-risk individuals and personalize support |

| Identify environmental and community health factors |

| – Record environmental and community health factors, such as living situation, occupation, context for identity, and psychological support |

| – Link the patient's environmental health factors to public health data and proactively identify relevant health needs |

| Integrate and share clinical and community-based care |

| – Identify community resources, programs, and caregivers that may support a patient's healthcare needs |

| – Allow communication with and shared access to EHR information for community caregivers |

| – Provide real-time coverage assessment and cost information about community resources |

| Primary care attribute: integrated |

| Integrate care settings |

| – Support the integration of clinical care and mental health |

| – Support the integration of clinical care and public health |

| Support the individual needs of practices |

| – Allow for local tailoring of content, display, and functionality while maintaining necessary standardization |

| – Embed functionality and tools for continuing medical education and maintenance of certification |

| Support national health recommendations and priorities |

| – Ensure that patient health information is collected with adequate detail to support national guidelines |

| – Integrate national guidelines into the EHR |

| – Supply clinicians and patients with timely prompts to support care |

| Allow population management |

| – Provide tools to track patient population health, adjusted for illness severity, and nationally/regionally benchmarked |

| – Provide tools to identify and reach out to patients overdue for care |

| – Include bidirectional flow of information to and from public health, cancer, immunization, and specialized registries |

| – Integrate local and national benchmarking into outcomes reports |

| Promote accountability for care |

| – Document important outcomes to patients and public health entities |

| – Allow information sharing and collaboration with population health partners |

Accessibility

To increase clinician accessibility, EHRs need to reduce documentation burden, help clinicians move beyond visits to deliver care, and allow clinicians to evaluate, monitor, and improve accessibility. Current EHRs essentially add a ‘third party’ to the examination room, competing with patients for clinician attention.33 34 This effect is greater when information is difficult to access or when documentation is time consuming.

If EHRs could easily aggregate and accept structured clinical data from external sources, they might reduce documentation workload, allowing the clinician to be fully present for the patient. Objectives require the ability to view, download, and transmit health information, but not update a clinician's EHR.35 To extend care outside visits, clinicians need enhanced electronic communication tools coupled with capacity for patients to electronically share health information (eg, pictures, device data). Interactions with patients could expand beyond messaging and include video conferencing, yet clinicians report that EHRs lack even basic communication functions.36

Coordination

Clinicians need EHRs that can coordinate and track care delivery across all clinical settings. Stage 2 MU objectives advance the creation and use of information exchanges, an important prerequisite for coordinating care. While the ability to exchange information must exist in all certified EHRs, they often require the creation of individualized and costly interfaces. As a result, clinicians in small to medium sized practices are largely excluded.37 38 Practices need access to ‘out of the box’ information exchanges that can easily send and receive a patient's health information. To have this functionality, EHRs need to adopt standard data models, coding systems, and vocabularies; clinicians need to adopt standardized methods for recording and tracking patient data.

Through PCMH and ACO initiatives, practices are expanding staff roles, creating care teams, and partnering a growing cadre of ancillary services.27–30 Clinicians will need EHRs that allow the electronic formation of teams with defined member roles, mechanisms to distribute tasks, processes for communication, and tools to track patient progress. These functions will need to extend beyond individual practices to integrate a range of clinicians and services in multiple healthcare settings and the community. Such functionality is essential to support clinical–mental health and primary care–public health integrations.39

A more fundamental deficiency for supporting coordination is EHRs’ focus on information documentation rather than extraction. Clinicians need a dashboard that synthesizes and prioritizes information across clinicians and settings to clearly show what has happened to a patient or what is happening within a panel of patients. A patient dashboard might show the sequence of clinicians that have seen the patient, changes in medications and diagnoses, and results from tests and procedures. A panel dashboard might show urgent messages or a list of patients seen in an acute care facility or admitted to the hospital.

Sustained care

To promote sustained care, MU only mandates that EHRs have reminders and generate registries. More is needed to promote both continuity and longitudinality. Continuity requires establishing and defining relationships and tracking how well relationships are maintained. EHRs need to allow patients to identify their clinicians. Clinicians need to define and track their patient panel size.

Clinicians need EHRs that have evolved beyond merely linking data according to data type (laboratory results, medications) or units of service (visits) in support of fee-for-service billing to provide the capacity to view episodes of care and display the chronological progression of signs and symptoms.40–42 For chronic conditions, EHRs could make it easy, within the same graphic representation, to see a timeline of laboratory results, medication changes, and symptom/disease evolution.

Comprehensiveness

MU has begun to advance data acquisition and documentation, basic decision support, and outcome tracking, but objectives remain process- (eg, record smoking status) and disease-focused. Primary care addresses the entire health spectrum and will need EHRs with more robust decision support to address all of prevention, acute care, chronic care, and mental health.43 44 To provide comprehensive care, clinicians need accurate health information. Beyond medication reconciliation, no objectives address information accuracy. EHRs could be configured to automate resolution of outdated information, identify data inconsistencies, and allow patients to participate in the reconciliation process.

Partnership with patients

Care needs to be tailored to each individual through shared decision-making and patient and family engagement.45 Objectives do little to support this, beyond sharing clinical summaries, providing basic educational resources, and documenting advanced directives. Contextual factors that influence decision-making (eg, goals, values, preferences, priorities, resources) need to be included in EHRs. EHRs need to clarify how decisions are made, initiate delivery of decision-support material, and integrate use of materials into encounters.46 47 The record should capture and document a patient's readiness to change unhealthy behaviors and also appropriately provide tailored prompts and materials to clinicians, patients, and families to better motivate and support change.47 Integrated health risk appraisals and other prioritization tools completed by patients can further help to move beyond disease-oriented care to goal-directed care.48 49

Person-centered

An understanding of the patient is central to creating long-term partnerships. The current objectives of recording demographics and family history do not support addressing whole-person care in the context of family and community. Person-centered care requires integration of social, cultural, and community context, biomedical, behavioral, and social risks, and personal goals and preferences.50 A person-centered summary, or ‘patient profile,’ should be available as a dashboard in the EHR, and decision-support tools should be tailored on the basis of these factors. Through patient portals, patients should be able to enter and edit their own information to improve accuracy and ease of data collection.

Integration

Clinicians need EHRs to serve as the information backbone across all primary care attributes throughout a clinician's practice, community, and career.14 27–30 Clinicians will need more robust clinical decision support that facilitates integration of all aspects of evidence-based guidelines, including high-risk individuals, guideline exceptions, influence of comorbidities, and patient preference.51 Current decision support is too simplistic, resulting in inaccurate prompts, alert fatigue, and inappropriate care.52 53 Greater federal coordination is needed to ensure that decision supports are implemented consistent with, and prioritized to, national needs.54–56

At the practice level, clinicians need more effective population-management tools. They need to be able to generate their own quality reports on demand, tailor reports to individual needs, and seamlessly move from population measures to initiating care delivery for patients in need of services.57 Important clinical outcomes, such as death, hospitalization, quality of life, and satisfaction with care, need to be systematically documented, tracked, and benchmarked. Given that information and patient needs vary between clinicians, EHRs need to allow local tailoring of functionality and content while maintaining standardization.

Throughout their careers, clinicians must maintain competencies and core skills, demonstrated through board (re)certification and maintenance of certification. To support this process, clinicians need tools embedded in EHRs to measure, trend, and benchmark performance, conduct knowledge assessments based on practice behaviors, and support continuous quality improvement.58

Discussion

Providing primary care is an important but daunting task, and designing EHRs to support primary care is equally challenging. The systematic process of comparing the stage 2 MU objectives with the IOM core attributes of primary care demonstrates that EHRs are not being required to consistently support all attributes of primary care.

As detailed in box 1, this analysis suggests that primary care needs additional EHR functions, but some are more critical than others. High-priority items per group consensus include:

Enhancing the extraction, interpretation, and prioritization of critical health information for individual patients and a clinician's patient panel;

Advancing information exchange to coordinate care across clinicians and settings;

Greater patient engagement;

Population-management tools to deliver care;

Reduction in documentation burden;

Better integration of care across settings.

It will be tempting for ONC and EHR vendors to discount these suggestions, stating that the issue is one of implementation and not development. However, clinician input and review of this article, as well as the literature, reveal that major advances in EHRs are needed. Take for example the objective to ‘view, download, and transmit health information’; an EHR can meet this requirement without being functional by merely having the capability to assemble and send information.59 60 This does not require data integration, update EHR content, provide care coordination, or even provide an easy transfer mechanism.

The approach used in this article of comparing the stage 2 MU objectives with the IOM core attributes of primary care has several limitations. First, while MU has incentivized EHR advances, EHRs have functionality not defined by MU objectives. Second, neither MU objectives nor EHR functionality were explicitly designed around primary care attributes. Although categorizing existing objectives and desired EHR additions is a useful and systematic approach, it is a subjective process. Third, the recommendations made in this article are not prescriptively detailed. Many EHR additions and enhancements will require innovative and novel ideas and solutions. This article purposefully focuses on what primary care clinicians think they need and not what can easily be done. Fourth, the stage 3 MU objectives currently under review may address some of the deficiencies identified in this article. Finally, just because there is a gap in EHR functionality does not mean that adding the functionality will improve outcomes. Research is needed to ensure that functions work and do not introduce unintended consequences.

More is outlined in this article than can be accomplished by MU or EHR developers alone. Years of effort, from many entities, are needed to improve EHR functionality. Some functions will be technically difficult; others may require fundamental EHR redesign. Some functions may be delivered best through external applications that are easily integrated into EHRs. Finally, some functions will require infrastructure development, new business models, and policy changes outside the control of EHR developers, such as health information exchange advancement, data standardization, privacy and security regulatory reform, and integration of national guidelines and priorities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was reviewed and endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), and North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG). This work was partially supported by CTSA Grant Number ULTR00058 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). We would like to thank all the participants who provided meaningful input into the content of this article and its recommendations including the NAPCRG's Health Information Technology Committee, AAFP National Research Network (NRN), Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN), OCHIN, Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), Robert Bernstein PhD MDCM, Brendan Delany MD, Elias Brandt, Emily Eaton, Kurtis Elward MD, Thomas Ehrlich MD, Roland Grad MD CM MSc, Sarah Gwynne AM, John Hughes MD, Samuel Jones MD, Thomas Kuhn MD, Susan Lin DrPh, John Machado, David Mehr MD MS, Zsolt Nagykaldi PhD, Kevin Pearce, Michael Raddock MD, Vanessa Short MPH, Alexander Singer MD, Karen Tu MD MSc, Edward Zimmerman MS. We would also like to especially thank Laura Nichols MS for organizing and coordinating writing activities. A modified version of this article was submitted to the Office of the National Coordinator's Health Information Technology Policy Committee (HITPC) as a joint policy statement from AAFP, AAP, ABFM, and NAPCRG to inform stage 3 MU Recommendations on January 14, 2013.

Footnotes

Contributors: All listed authors substantially contributed to the conception and design of the framework to generate recommendations, development of the manuscript's recommendation, initial drafting and/or revision of the manuscript, and review and final approval of the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:742–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, et al. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:732–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou L, Soran CS, Jenter CA, et al. The relationship between electronic health record use and quality of care over time. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:457–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. 2009. [cited 2012 Apr]. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c111:H.R.1:

- 5.Steinbrook R. Health care and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1057–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Official Web Site for the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs. 2012. [cited 2012 Apr]. https://www.cms.gov/ehrincentiveprograms/

- 7.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010;363:501–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackerman K. Heavy hitters hit HIMSS stages to stump for health IT, 2011. [cited 2012 Mar]. http://www.ihealthbeat.org/features/2011/heavy-hitters-hit-himss-stages-to-stump-for-health-it.aspx

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs: milestone timeline. [cited 2012 Sept]. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EHRIncentProgtimeline508V1.pdf

- 10.Health IT Strategic Plan 2011–2015. 2011. [cited 2011 May]. http://healthit.hhs.gov/StrategicPlan

- 11.Electronic health records and meaningful use. 2012. [cited 2012 Feb]. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=2996&mode=2

- 12.Seidman J, Tagalicod R. Public input shaped the guiding principles for stage 2 meaningful use NPRM. HealthIT Buzz, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitton A, Flier LA, Jha AK. Health information technology in the era of care delivery reform: to what end? JAMA 2012;307:2593–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, et al. The Pediatric Alliance for Coordinated Care: evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics 2004;113(5 Suppl):1507–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HealthIT.gov. Health IT Policy Committee—Accountable Care. 2013. [cited 2013 October]. http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/federal-advisory-committees-facas/accountable-care

- 16.Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, et al. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:457–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med 1961;265:885–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green LA, Fryer GE, Jr, Yawn BP, et al. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med 2001;344:2021–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao C-J. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). Electronic health record systems and intent to apply for meaningful use incentives among office-based physician practices: United States, 2001–2011. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Doctors and hospitals’ use of health IT more than doubles since 2012. 2013. [cited 2013 October]. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2013pres/05/20130522a.html

- 22.Edsall RL, Adler KG. User satisfaction with EHRs: report of a survey of 422 family physicians. Fam Pract Manag 2008;15:25–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:745–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiegel C. Stage 2 meaningful use rules sharply criticized by physicians. American Medical News. 2012. May 21

- 25.Lewis Dolan P. EHRs: A love-hate relationship. American Medical News. 2012. May 21

- 26.Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program—Stage 2. In: Federal Register Vol. 77 No. 45, editor. 42 CFR Parts 412, 413, and 495; 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2009. [cited 2011 May]. http://www.pcpcc.net/

- 28.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74:511–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devers K, Berenson RA. Can accountable care organizations improve the value of health care by solving the cost and quality quandries? Urban Institute. [cited 2012 Sept]. http://www.urban.org/publications/411975.html.

- 31.Tagalicod R, Reider J. Progress on adoption of electronic health records. CMS.gov. 2013. [cited 2013 Dec]. http://www.cms.gov/eHealth/ListServ_Stage3Implementation.html

- 32.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Stage 1 vs. Stage 2 Comparison for Eligible Professionals. [cited 2012 Sep]. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage1vsStage2CompTablesforEP.pdf

- 33.Lown BA, Rodriguez D. Commentary: Lost in translation? How electronic health records structure communication, relationships, and meaning. Acad Med 2012;87:392–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toll E. A piece of my mind. The cost of technology. JAMA 2012;307: 2497–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borkan J, Eaton CB, Novillo-Ortiz D, et al. Renewing primary care: lessons learned from the Spanish health care system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1432–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, et al. Primary care practitioners’ views on test result management in EHR-enabled health systems: a national survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;20:727–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jha AK, Ferris TG, Donelan K, et al. How Common Are Electronic Health Records In The United States? A Summary of the Evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:w496–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care--a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med 2008;359:50–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.IOM (Institute of Medicine). Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips RL, Klinkman MS, Green L. Harmonizing primary care: clinical classification and data standards. Washington, DC: American Academy of Family Physicians, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamberts H, Hofmans-Okkes I. Episode of care: a core concept in family practice. J Fam Pract 1996;42:161–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H. The probability of specific diagnoses for patients presenting with common symptoms to Dutch family physicians. J Fam Pract 2002;51:31–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Chambliss ML, et al. Answering physicians’ clinical questions: obstacles and potential solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:217–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA 2012;307:1801–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH. Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention. A suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med 2004;26:56–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krist AH, Woolf SH. A vision for patient-centered health information systems. JAMA 2011;305:300–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Estabrooks PA, Boyle M, Emmons KM, et al. Harmonized patient-reported data elements in the electronic health record: supporting meaningful use by primary care action on health behaviors and key psychosocial factors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:575–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mold JW, Blake GH, Becker LA. Goal-oriented medical care. Fam Med 1991;23: 46–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care--an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med 2012;366:777–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klinkman M, van Weel C. Prospects for person-centred diagnosis in general medicine. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:365–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riedmann D, Jung M, Hackl WO, et al. How to improve the delivery of medication alerts within computerized physician order entry systems: an international Delphi study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:760–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung M, Hoerbst A, Hackl WO, et al. Attitude of Physicians Towards Automatic Alerting in Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems. A Comparative International Survey. Methods Inf Med 2012;52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roshanov PS, Misra S, Gerstein HC, et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for chronic disease management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. IS 2011;6:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2012. [cited 2013 Jan]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx

- 55.The National Prevention Strategy. 2011. [cited 2011 July]. http://www.healthcare.gov/center/councils/nphpphc/index.html

- 56.Health eDecisions Standards and Interoperability Framework Initiative. [cited 2013 October]. http://wiki.siframework.org/Health+eDecisions+Homepage

- 57.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. 2012. [cited 2013 Jan]. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html

- 58.American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Maintenance of Certification. 2012. [cited 2013 Jan]. http://www.abms.org/maintenance_of_certification/ABMS_MOC.aspx

- 59.HITSP summary documents using HL7 continuity of care document (CCD) component 32. New York (NY): HITSP (US): United States. Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP). 2009 Jul 08. Version 2.5

- 60.ASTM International. Standard Specification for the Continuity of Care Record. 2012. [cited 2013 Jan]. http://www.astm.org/Standards/E2369.htm

- 61.Kuzel AJ. Ten steps to a patient-centered medical home. Fam Pract Manag 2009;16:18–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.