Abstract

Background: Although the protective effects of levocarnitine in patients with ischemic heart disease are related to the attenuation of oxidative stress injury, the exact mechanisms involved have yet to be fully understood. Our aim was to investigate the potential protective effects of levocarnitine pretreatment against oxidative stress in rat H9c2 cardiomyocytes.

Methods: Cardiomyocytes were exposed to H2O2 to create an oxidative stress model. The cells were pretreated with 50, 100, or 200 μM levocarnitine for 1 hour before H2O2 exposure.

Results: H2O2 exposure led to significant activation of oxidative stress in the cells, characterized by reduced viability, increased intracellular reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and reduced intracellular antioxidant activity. Mitochondrial dysfunction was also observed following H2O2 exposure, reflected by the loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and intracellular adenosine triphosphate. These pathophysiological processes led to cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. More importantly, the levocarnitine pretreatment attenuated the H2O2-induced oxidative injury significantly, preserved mitochondrial function, and partially prevented cardiomyocyte apoptosis during the oxidative stress reaction. Western blotting analyses suggested that levocarnitine pretreatment increased plasma protein levels of Bcl-2, reduced Bax, and attenuated cytochrome C leakage from the mitochondria in the cells.

Conclusion: Our in vitro study indicated that levocarnitine pretreatment may protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-related damage.

Keywords: Levocarnitine, Oxidative stress, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Apoptosis, Ischemic heart disease.

Introduction

Despite significant improvement in treatment strategies in recent years, ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in both the developed 1 and developing countries 2. Studies from recent decades have confirmed that oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of various cardiovascular diseases 3-5, including IHD. Oxidative stress is characterized by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and reduced cellular antioxidant activity, leading to membrane lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction 6. If oxidative insult persists, programmed cell death will be initiated partially through the mitochondrial pathway, causing the loss of functional cardiomyocytes. Therefore, treatment strategies with the potential to prevent oxidative stress are considered valuable for patients with IHD 7, 8.

Levocarnitine is a naturally occurring essential co-factor of fatty acid metabolism that is synthesized endogenously or obtained from dietary sources 9. Physiologically, levocarnitine transports free fatty acids into the mitochondria, increasing the preferred substrate for oxidative metabolism in the heart 10. As β-oxidation of fatty acids is the major biogenesis process of the heart, and metabolic and energy dysfunction are acknowledged to play key roles in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases 11, 12, it is reasonable to hypothesize that levocarnitine supplementation may benefit IHD patients, perhaps by restoring energy and metabolic functions. Indeed, previous human studies suggested that levocarnitine supplementation was associated with significantly reduced mortality in patients experiencing acute myocardial infarction 13-15. Although some early experimental studies reported that the protective effects of levocarnitine in IHD patients were related to the attenuation of oxidative stress injury in the myocardium 16, 17, the exact mechanisms involved are still not fully understood.

Oxidative stress is mainly caused by excessive accumulation of ROS, which include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2-•), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH). H2O2 is a major component of ROS and is used extensively as an inducer in oxidative stress models, including many previous studies that evaluated the potential protective effects of levocarnitine against oxidative stress 18-20. As an inducer of oxidative stress, H2O2 does not initiate lipid peroxidation or oxidize DNA or amino acids on its own, but may cause such damage by inducing oxidative stress 21, 22. Therefore, the aim of the current study was investigating the potential protective effects of levocarnitine pretreatment on H2O2-induced oxidative stress in H9c2 rat cardiomyocytes in vitro, in particular, its effect on mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis.

Methods

H9c2 rat cardiomyocyte culture and H2O2 treatment

H9c2 embryonic rat heart-derived cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) and penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 μg/mL; both from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

We first determined the appropriate concentration of H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for mimicking oxidative stress-induced injury in cardiomyocytes. In the preliminary study, H9c2 cells were treated with 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, and 2000 μM H2O2 for 12 hours. We defined the appropriate H2O2 concentration as the lowest concentration that would lead to substantially reduced (about 50%) H9c2 cell viability when cells were treated for a relatively long duration, such as 12 hours. Viability was decreased in about 57% of H9c2 cells following 12-hour treatment with 200 μM H2O2. Therefore, we treated H9c2 cells with 200 μM H2O2 for 12 hours to establish the oxidative stress-induced injury model in cardiomyocytes; selection of the H2O2 concentration was also consistent with that of previous studies 19, 20.

Then, we evaluated the potential protective effects of levocarnitine (Sigma-Aldrich) against oxidative stress-induced injury in H9c2 cardiomyocytes through pretreatment with 10, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 1500, or 2000 μM levocarnitine 1 hour prior to H2O2 exposure. We selected the three most effective concentrations for subsequent analyses.

Therefore, this study comprised six groups: (1) control: cells cultured under normal incubation conditions; (2) levocarnitine: cells treated with 200 μM levocarnitine for 1 hour without H2O2 exposure; (3) H2O2 model: cells exposed to H2O2 without levocarnitine pretreatment; (4~6) levocarnitine pretreatment: cells pretreated with three different concentrations of levocarnitine 1 hour prior to H2O2 exposure.

Determination of cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, H9c2 cells from the different treatment groups were seeded in 96-well plates at 103 cells/well (104 cells/mL, 100 μL/well) and 10 μL CCK-8 solution was administered into each well to determine cell viability. After 4-hour incubation at 37°C, the absorbance in each well was detected at 450 nm (reference 650 nm) using a microplate reader (Tecan GENios, Austria). Each experiment was repeated five times and the data were expressed as a percentage of the control.

Determination of intracellular ROS

On its own, the fluorescent probe 29, 79-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) is non-fluorescent, and can cross cell membranes freely. Esterases hydrolyze intracellular DCFH-DA to produce DCFH, and intracellular ROS can oxidize the non-fluorescent DCFH to generate fluorescent 29, 79-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Intracellular ROS in H9c2 cells were thus detected based on the fluorescence intensity of DCF in a fluorometer using an ROS detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) after treatment, and then the ROS detection solution was added. Cells were stained at 37°C in the dark for 20 min and visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Leica, Germany). Fluorescence was read on a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP5 AOBS, Leica) at 504 nm excitation and 524 nm emission wavelengths. Fold-increases in ROS level were determined by comparison with the control group.

Measurement of lactate dehydrogenase activity

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured as LDH released in the culture medium. Briefly, 0.2 mL culture medium from each group was obtained after treatment and assayed for LDH activity using commercial kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and a microplate reader (Tecan GENios) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Determination of malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase activity

After treatment, cells from each group were washed with cold PBS three times, harvested with 0.25% trypsin, and centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet sonicated in cold PBS. After centrifugation (800 ×g, 5 min), the supernatant was immediately evaluated for malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) cellular activity using commercial kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) with a spectrophotometer according to the manufacturer's protocols. The protein content of the cell homogenates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay according to the kit instructions.

Measurement of mitochondrial transmembrane potential

We used 5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Sigma-Aldrich) to determine changes in mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm). JC-1 (10 μL; 200 μM; final concentration 2 μM) was added to H9c2 cells on coverslips, incubated for 45 min in the dark, and washed twice with PBS. JC-1-labeled cells were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP5 AOBS). JC-1 fluorescence was measured from a single excitation wavelength (490 nm) with dual emission (shift from green at 530 nm to red at 590 nm). Loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm is presented as the relative ratio of green to red fluorescence.

Measurement of intracellular adenosine triphosphate

Cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was measured by an ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). After treatment, cells were washed with PBS, lysed, and the supernatant collected. Proteins (10 μg/20 μL) were added to a white OptiPlate (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and the reaction initiated by adding reconstituted reagent. Luminescence was measured using a microplate reader (Tecan GENios).

Determination of cardiomyocyte apoptosis

Apoptosis was measured with a commercial kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) as recommended by the manufacturer. Approximately 105 H9c2 cells were stained for 15 min with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide at room temperature in the dark. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry with a cytometer (BD LSRII; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). Distribution of apoptotic cells was analyzed using FlowJo 7.6 software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

Western blotting

Total proteins from H9c2 cells were extracted, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and detected using an ECL Western Blotting Detection Kit (GE Healthcare, UK). Antibodies against β-actin, Bcl-2, Bax, and cytochrome C were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Digital images were analyzed for densitometry using Image Lab™ Software Version 3.0 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analyses

SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences among groups were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (H2O2 × Levocarnitine), followed by the least significant difference test. Statistical significance was indicated when p < 0.05.

Results

Levocarnitine pretreatment protected cardiomyocytes from H2O2-induced decrease in cell viability

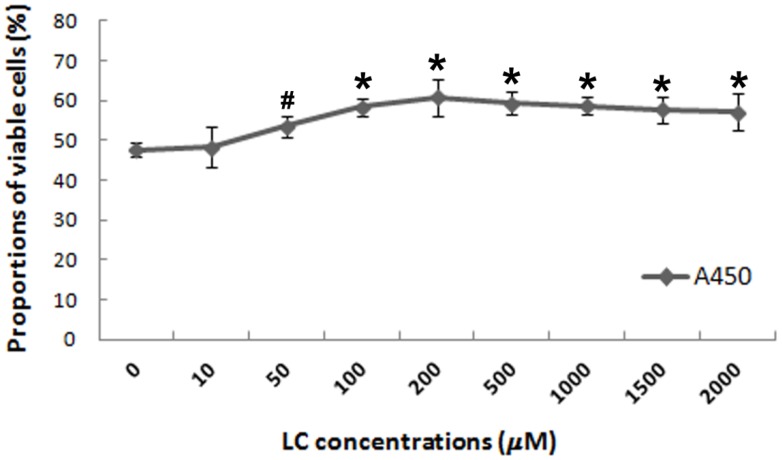

To evaluate the potential protective effects of levocarnitine against oxidative stress-induced injury in H9c2 cardiomyocytes, we investigated whether 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment would attenuate H2O2-induced cell death. Pretreatment with 10 μM levocarnitine significantly preserved H9c2 cardiomyocyte viability as compared with the control group that received no levocarnitine (p< 0.05, Figure 1). The protective effects of levocarnitine pretreatment on cell viability were dose-dependent, with 200 μM levocarnitine achieving the strongest effect. Therefore, we used 50, 100, and 200 μM levocarnitine in subsequent analyses to observe the potential dose-dependent effect of levocarnitine.

Figure 1.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on H2O2-induced loss of H9c2 cell viability. LC, Levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). #p< 0.05 compared with the group with no pretreatment; *p< 0.01 compared with the group with no pretreatment.

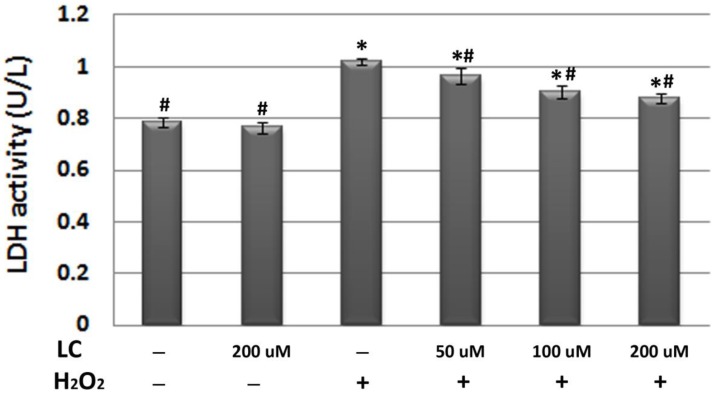

Levocarnitine pretreatment attenuated H2O2-induced LDH release

To confirm the protective effects of levocarnitine pretreatment against oxidative stress-induced cell injury, we measured LDH release in each group. Plasma LDH activity reflects the cell membrane damage caused by oxidative stress. LDH activity in the culture medium of the model group was significantly higher than that in the control group (p< 0.05, Figure 2), suggesting that 12-hour H2O2 exposure led to severe cell injury. It appeared that levocarnitine pretreatment significantly reduced the levels of LDH activity in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on LDH activity in each group. LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; LC, levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

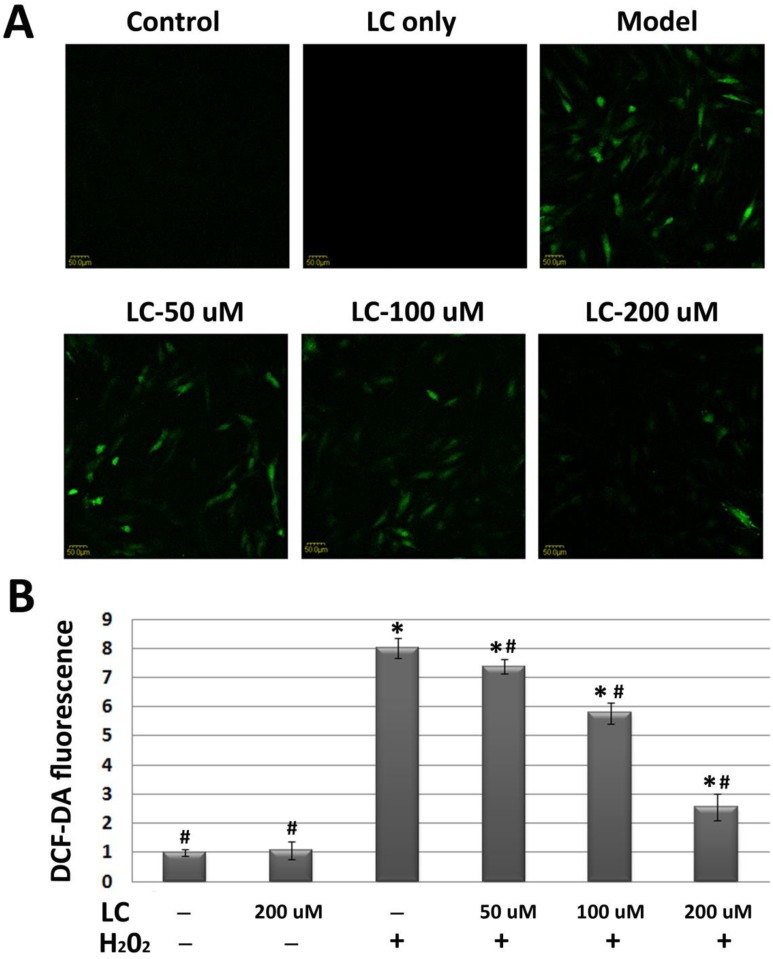

Levocarnitine pretreatment reduced H2O2-induced oxidative stress

To evaluate whether the protective effects of levocarnitine on H9c2 cardiomyocytes were related to reduced oxidative stress, we evaluated the effects of levocarnitine pretreatment on intracellular ROS in H9c2 cells. H2O2 exposure increased cellular ROS production significantly, reflected by the higher DCF-DA fluorescence intensity in the model group compared with the control group (p< 0.05, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on H2O2-induced ROS accumulation in H9c2 cells. (A) Representative images of ROS staining. Cells with green fluorescence indicate elevated intracellular ROS. (B) Quantitative analysis of ROS staining. ROS, Reactive oxygen species; LC, levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

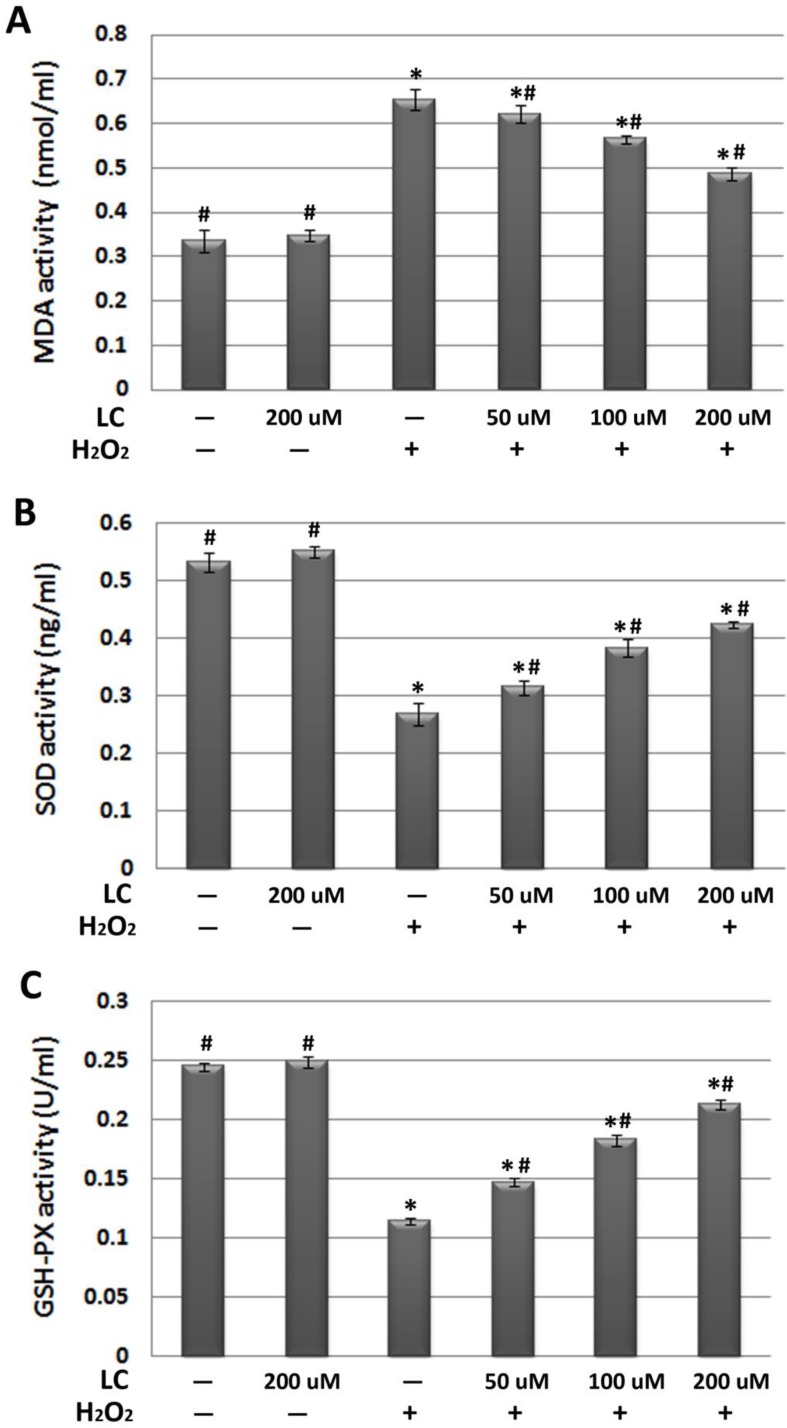

Interestingly, we found that levocarnitine pretreatment reduced intracellular ROS, suggesting that levocarnitine may reduce the ROS production induced by H2O2 exposure. As excessive ROS may lead to severe cellular membrane damage through peroxidative lipid injury, we explored whether levocarnitine pretreatment reduced MDA activity, which is a marker of the extent of lipid peroxidation. Levocarnitine pretreatment was associated with significantly reduced MDA activity, confirming that levocarnitine alleviated H2O2-induced lipid peroxidation (Figure 4A). Lastly, we attempted to clarify whether levocarnitine pretreatment affected intracellular antioxidant activity. Levocarnitine pretreatment partially ameliorated the loss of cellular antioxidants caused by H2O2 exposure, including SOD and GSH-Px, and these effects appeared to be dose-dependent (Figure 4B and 4C).

Figure 4.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on (A) MDA, (B) SOD, and (C) GSH-Px activity in each group. MDA, Malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; LC, levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

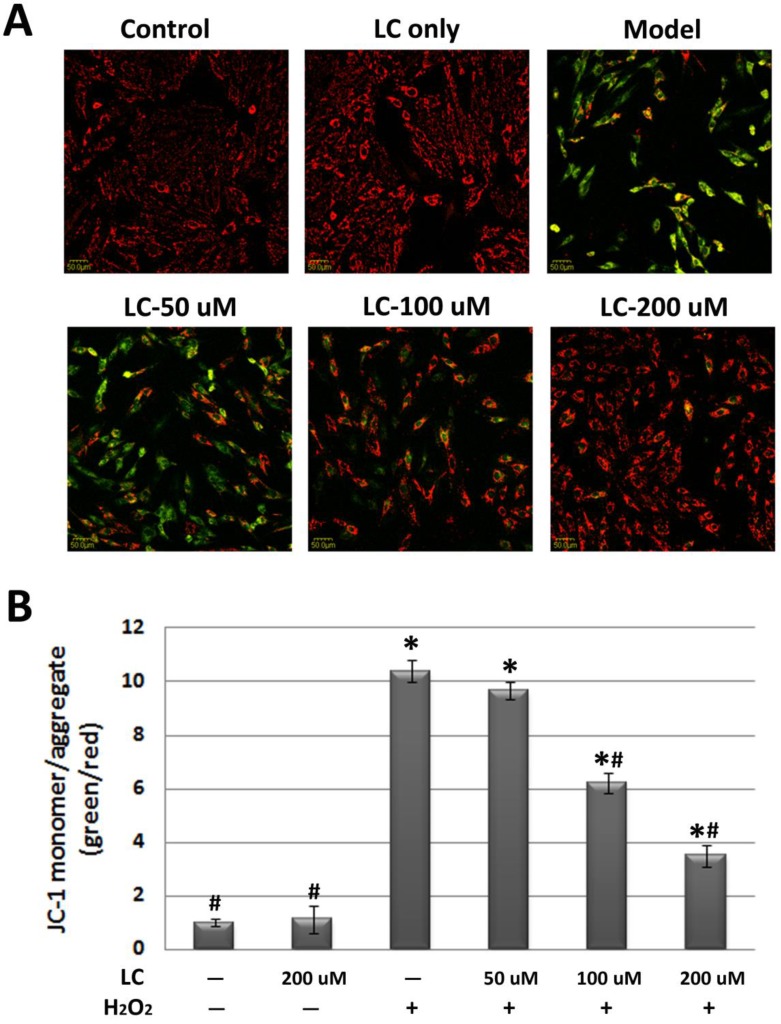

Levocarnitine pretreatment attenuated H2O2-induced loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm and ATP

As mitochondrial ΔΨm is fundamental to the maintenance of mitochondrial physiological function 23, we observed the effect of levocarnitine on mitochondrial ΔΨm. JC-1 staining revealed significant loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm in the model group (Figure 5). Pretreatment with 100 and 200 μM levocarnitine significantly attenuated mitochondrial ΔΨm loss (p< 0.05), although the effect of 50 μM levocarnitine was not statistically significant. To evaluate the protective effects of levocarnitine on mitochondrial function, we measured intracellular ATP in each group. Cellular ATP was significantly reduced in the model group compared with the control group (p< 0.05, Figure 6), indicating that oxidative stress induced by H2O2 exposure caused significant cellular energy metabolism dysfunction. Notably, levocarnitine pretreatment partially prevented the oxidative stress-induced loss of ATP in cardiomyocytes dose-dependently, possibly through the preservation of mitochondrial function.

Figure 5.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on H2O2-induced loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm in H9c2 cells (JC-1 staining). (A) Representative images of JC-1 staining. (B) Quantitative analysis of JC-1 staining. LC, Levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

Figure 6.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on cellular ATP. LC, Levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

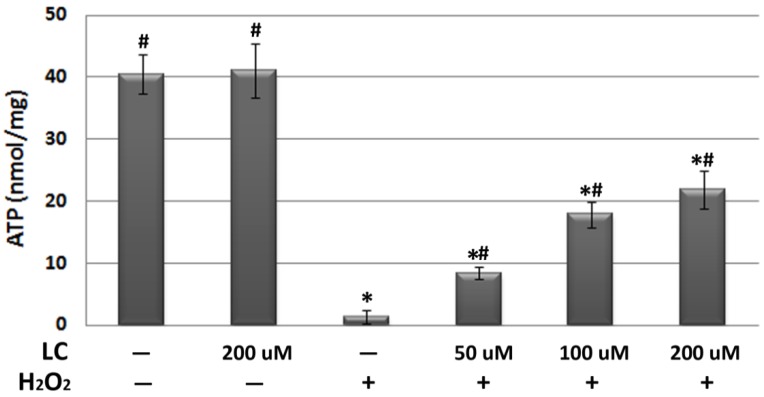

Levocarnitine pretreatment prevented H2O2-induced apoptosis by regulating key molecules in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway

As oxidative stress and related mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to cardiomyocyte apoptosis, which has been recognized as playing a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of various cardiovascular diseases 24, we investigated the effects of levocarnitine on H2O2-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. In this study, cells were distinguished as living (annexin V-/propidium iodide [PI]-), early apoptotic (annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (annexin V-/PI+). Flow cytometry analyses (Figure 7 and Table 1) indicated that levocarnitine pretreatment was associated with significantly reduced early- and the late-phase oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, perhaps dose-dependently. Additionally, there remained more living cells in the levocarnitine-pretreated groups as compared with the model group.

Figure 7.

Representative images of the effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on H2O2-induced apoptotic cell distribution in H9c2 cells. LC, Levocarnitine.

Table 1.

Effects of levocarnitine pretreatment on H9c2 cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

| Viable cells (annexin V-/PI-, %) |

Early-phase apoptosis (annexin V+/PI-, %) |

Late-phase apoptosis (annexin V+/PI+, %) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 94.3 ± 3.44# | 1.06 ± 0.05# | 2.05 ± 0.78# |

| LC only | 93.12 ± 4.01# | 1.81 ± 0.46# | 2.69 ± 0.43# |

| Model | 64.79 ± 2.86* | 18.41 ± 1.68* | 14.89 ± 2.69* |

| LC-50 μM | 75.84 ± 6.92*# | 13.47 ± 3.99*# | 10.08 ± 4.08*# |

| LC-100 μM | 80.03 ± 5.17*# | 9.97 ± 4.63*# | 6.93 ± 3.55*# |

| LC-200 μM | 89.25 ± 7.32*# | 5.76 ± 2.21*# | 3.42 ± 1.71*# |

Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group;#p< 0.05 compared with the model groups. LC, Levocarnitine; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PI, propidium iodide.

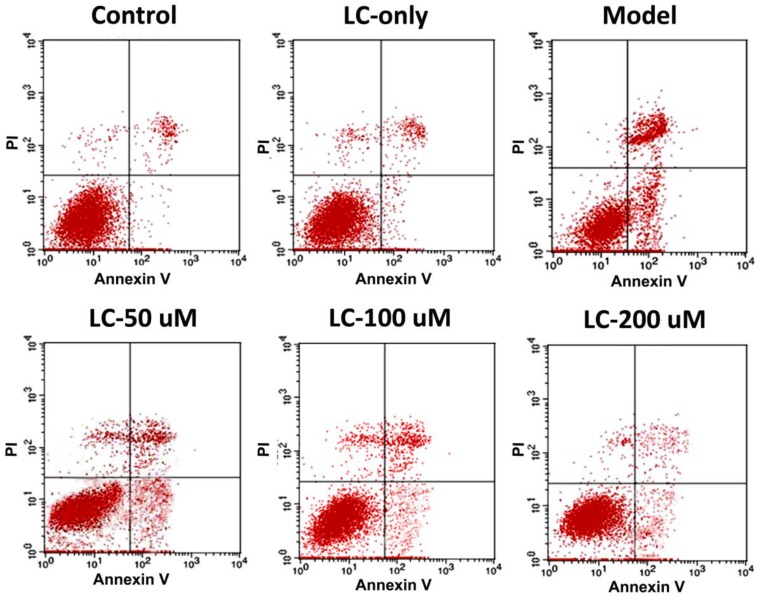

To investigate the potential molecular mechanisms involved, we performed western blotting to explore the effects of levocarnitine pretreatment on the related proteins in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Levocarnitine pretreatment restored protein levels of the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-2 and reduced expression of the apoptotic molecule Bax (Figure 8). Levocarnitine pretreatment also attenuated cytochrome C release dose-dependently. These results suggest that levocarnitine may partially prevent oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Figure 8.

Effects of 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment on protein levels of apoptosis-related molecules in H9c2 cells. (A) Representative western blots. (B) Quantitative analyses for Bcl-2. (C) Quantitative analyses for Bax. (D) Quantitative analyses for cytochrome C. LC, Levocarnitine. Data presented are the mean ± SEM (n = 4~6 per group). *p< 0.05 compared with the control group; #p< 0.05 compared with the model group.

Discussion

We created a model of H2O2-induced oxidative stress in H9c2 cardiomyocytes and found that H2O2 exposure led to significant activated oxidative stress in the cells, which was characterized by reduced cell viability, increased intracellular ROS and lipid peroxidation, and reduced intracellular antioxidant activity. Mitochondrial dysfunction was also observed following H2O2 exposure, reflected by the loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm and intracellular ATP. These pathophysiological processes led to apoptosis by activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. More importantly, the 1-hour levocarnitine pretreatment significantly attenuated the above H2O2-induced oxidative injury, preserved mitochondrial function, and partially prevented apoptosis during the oxidative stress reaction. The potential protective effects of levocarnitine pretreatment against oxidative stress-related injury in H9c2 cells appeared dose-dependent. These results expand our insight into the potential benefits of levocarnitine for patients with oxidative stress-related cardiovascular diseases, such as IHD.

Previous studies have reported the protective effects of levocarnitine against oxidative stress-related injury. Calo et al. found that in human endothelial cells, levocarnitine stimulated gene and protein expression of heme oxygenase-1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase, two well-known antioxidants upregulated during oxidative stress 16. These findings highlight the possibility that levocarnitine supplementation may be protective against oxidative stress-related cardiovascular risk factors and myocardial damage 16. A subsequent study of neonatal cardiomyocytes also suggested that levocarnitine protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced apoptosis, in part through the prostacyclin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling pathways 17. As oxidative stress plays an important role in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy 25, these results also support the premise that the cardioprotective effects of levocarnitine are at least partially dependent on its action against the oxidative stress reaction. In addition to cardiovascular system studies, evidence from human peripheral blood lymphocytes 26, human retinal pigment epithelial cells 27, and human hepatocytes 28 also support the potential antioxidative effects of levocarnitine. Our results confirmed the above findings by demonstrating that levocarnitine pretreatment preserved cell viability, reduced ROS, increased antioxidant activity, and attenuated lipid peroxidation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes exposed to H2O2.

It is well established that the mitochondria play a key role in energy metabolism and biogenesis in cardiomyocytes 11. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction is an important feature during the pathophysiological process of oxidative stress 12. Considering levocarnitine is located between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, and physically functions as a free fatty acid transporter into the mitochondria for β-oxidation 29, it appears reasonable to propose that the maintenance of mitochondrial function and energy metabolism by levocarnitine partially mediates the potential protective effects of levocarnitine during oxidative stress. Although previous studies have suggested the potential benefit of levocarnitine supplementation to mitochondrial function and energy metabolism 30, 31, our results confirm that these effects are the means by which levocarnitine pretreatment attenuates oxidative stress-induced damage in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Indeed, our study indicated that levocarnitine pretreatment preserved cellular ATP and significantly prevented the loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm, thereby preserving the cardiomyocyte energy supply during oxidative stress. These results are consistent with previously reported findings 32.

In addition to energy metabolism, another important function of the mitochondria is the regulation of apoptosis. During oxidative stress, excessive ROS production, most likely from both H2O2 treatment and subsequent mitochondrial damage, may create a vicious cycle by leading to severe mitochondrial membrane damage, loss of mitochondrial ΔΨm, and subsequent cytochrome C release, thus initiating the intrinsic apoptotic pathway 33. Moreover, some apoptotic process regulatory proteins, including Bcl-2 and Bax, are located in the mitochondrial membrane. Imbalance of these regulatory proteins also has an important effect on apoptosis 34. Our findings demonstrate that levocarnitine pretreatment may also attenuate oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via regulation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and Bcl-2 family proteins. As loss of functional cardiomyocytes is one of the important mechanisms in the pathogenesis and progression of cardiovascular diseases 35, the benefits of levocarnitine against oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte injury may also include attenuation of apoptosis.

In conclusion, our in vitro study indicated that levocarnitine pretreatment may protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-related damage by inhibiting ROS production, increasing intracellular antioxidants, preserving mitochondrial function, and attenuating apoptosis. These results may partially explain the clinical benefit of levocarnitine in patients with prior myocardial infarction 15. These results require verification in animal studies in the future.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Jiang H, Ge J. Epidemiology and clinical management of cardiomyopathies and heart failure in China. Heart. 2009;95:1727–31. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molavi B, Mehta JL. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease: molecular basis of its deleterious effects, its detection, and therapeutic considerations. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:488–93. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000133657.77024.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachidanandam K, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease: antioxidants and unresolved issues. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2005;23:115–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2005.tb00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon IM, Faux SP. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease: novel tools give (free) radical insight. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha M, Apostolova N, Hernandez-Mijares A. et al. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: mitochondria-targeted therapeutics. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:3827–41. doi: 10.2174/092986710793205444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton CA, Miller WH, Al-Benna S. et al. Strategies to reduce oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:219–34. doi: 10.1042/CS20030379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munzel T, Gori T, Bruno RM. et al. Is oxidative stress a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease? Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2741–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mingorance C, Rodriguez-Rodriguez R, Justo ML. et al. Pharmacological effects and clinical applications of propionyl-L-carnitine. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:279–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcovina SM, Sirtori C, Peracino A. et al. Translating the basic knowledge of mitochondrial functions to metabolic therapy: role of L-carnitine. Transl Res. 2013;161:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren J, Pulakat L, Whaley-Connell A. et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0663-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marzetti E, Csiszar A, Dutta D. et al. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and altered autophagy in cardiovascular aging and disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H459–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00936.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Pasquale B, Righetti G, Menotti A. [L-carnitine for the treatment of acute myocardial infarct] Cardiologia. 1990;35:591–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davini P, Bigalli A, Lamanna F. et al. Controlled study on L-carnitine therapeutic efficacy in post-infarction. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1992;18:355–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H. et al. L-carnitine in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calo LA, Pagnin E, Davis PA. et al. Antioxidant effect of L-carnitine and its short chain esters: relevance for the protection from oxidative stress related cardiovascular damage. Int J Cardiol. 2006;107:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao HH, Liu JC, Hong HJ. et al. L-carnitine reduces doxorubicin-induced apoptosis through a prostacyclin-mediated pathway in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Int J Cardiol. 2011;146:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eguchi M, Liu Y, Shin EJ. et al. Leptin protects H9c2 rat cardiomyocytes from H2O2-induced apoptosis. FEBS J. 2008;275:3136–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong XF, Huang GD, Luo T. et al. Protective effect of rhein against oxidative stress-related endothelial cell injury. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1261–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang G, Zhang D, Yu H. et al. Cardioprotective effects of exenatide against oxidative stress-induced injury. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:1011–20. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antunes F, Cadenas E. Cellular titration of apoptosis with steady state concentrations of H(2)O(2): submicromolar levels of H(2)O(2) induce apoptosis through Fenton chemistry independent of the cellular thiol state. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1008–18. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian J, Jiang F, Wang B. et al. Ophiopogonin D prevents H2O2-induced injury in primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:438–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perl A, Banki K. Genetic and metabolic control of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and reactive oxygen intermediate production in HIV disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:551–73. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:449–56. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee K, Zhang J, Honbo N. et al. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology. 2010;115:155–62. doi: 10.1159/000265166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia CL, Filippi S, Mosesso P. et al. The protective effect of L-carnitine in peripheral blood human lymphocytes exposed to oxidative agents. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:21–7. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gei065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamsi FA, Chaudhry IA, Boulton ME. et al. L-carnitine protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative damage. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:575–84. doi: 10.1080/02713680701363833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li JL, Wang QY, Luan HY. et al. Effects of L-carnitine against oxidative stress in human hepatocytes: involvement of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. J Biomed Sci. 2012;19:32. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pekala J, Patkowska-Sokola B, Bodkowski R. et al. L-carnitine--metabolic functions and meaning in humans life. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:667–78. doi: 10.2174/138920011796504536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alesci S, De Martino MU, Mirani M. et al. L-carnitine: A nutritional modulator of glucocorticoid receptor functions. FASEB J. 2003;17:1553–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1024fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombani P, Wenk C, Kunz I. et al. Effects of L-carnitine supplementation on physical performance and energy metabolism of endurance-trained athletes: a double-blind crossover field study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1996;73:434–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00334420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyanagi E, Yano H, Uchida M. et al. Protective action of L-carnitine on cardiac mitochondrial function and structure against fatty acid stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han H, Long H, Wang H. et al. Progressive apoptotic cell death triggered by transient oxidative insult in H9c2 rat ventricular cells: a novel pattern of apoptosis and the mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2169–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00199.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suleiman MS, Halestrap AP, Griffiths EJ. Mitochondria: a target for myocardial protection. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;89:29–46. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee Y, Gustafsson AB. Role of apoptosis in cardiovascular disease. Apoptosis. 2009;14:536–48. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]