Abstract

There is consensus that physicians, health professionals and health care organizations should discuss harm that results from health care delivery (adverse events), including the reasons for harm, with patients and their families. Thought leaders and policy makers in the USA and Canada support this goal. However, there are gaps in both countries between patients and physicians in their attitudes about how errors should be handled, and between disclosure policies and their implementation in practice. This paper reviews the state of disclosure policy and practice in the two countries, and the barriers to full disclosure. Important barriers include fear of consequences, attitudes about disclosure, lack of skill and role models, and lack of peer and institutional support. The paper also describes the problem of the second victim, a corollary of disclosure whereby health care workers are also traumatized by the same events that harm patients. The presence of multiple practical and personal barriers to disclosure suggests the need for a comprehensive solution directed at multiple levels of the health care system, including health departments, institutions, local managers, professional staff, patients and families, and including legal, health system and local institutional support. At the local level, implementation could be based on a translating-evidence-into-practice framework. Applying this framework would involve the formation of teams, training, measurement and identification of local barriers to achieving universal disclosure of adverse events.

Significance for public health.

It is inevitable that some patients will be harmed rather than helped by health care. There is consensus that patients and their families must be told about these harmful events. However, there are gaps between patient and physician attitudes about how errors should be handled, and between disclosure policies and their implementation. There are important barriers that impede disclosure, including fear of consequences, attitudes about disclosure, lack of skill, and lack of institutional support. A related problem is that of the second victim, whereby health care workers are traumatized by the same harmful events. This can impair their performance and further compromise safety. The problem is unlikely to be solved by focusing solely on increasing disclosure. A comprehensive solution is needed, directed at multiple levels of the health care system, including health departments, institutions, local managers, professional staff, patients and families, and including legal, health system and local institutional support.

Key words: adverse events, disclosure, second victim, USA and Canada

Introduction

Patients deserve to know the reasons for unexpected clinical outcomes. Although an undesired outcome may represent the progression of disease, sometimes care is at fault. Harm from health care delivery may unfortunately occur despite the best of care. Such harm results most frequently from a recognized complication – an inherent risk of an investigation or treatment. For example, a patient with no previously known allergy to penicillin may suffer anaphylaxis from the drug. Harm may also result from failures in the structure and process of care, including issues in individual provider performance. The patient with a known allergy to penicillin reacting to the drug given by mistake would fall into this category. Various terms have been used to describe clinical events involving unintended harm from health care delivery. In this paper, we use the term adverse event to refer to patient harm caused by the care provided. We also use the term preventable adverse event, which is synonymous with harmful error.1,2

Disclosure to patients of harm from healthcare delivery is intrinsic to maintaining the trust between patients and healthcare professionals. Disclosure is used to refer to the process by which an adverse event is communicated to the patient. Much of this paper focuses on communication of adverse events to patients in which human error was involved. Some, particularly in the United States, would link disclosure to early offers of compensation and restitution, but this is not uniform within the United States or Canada.

The purpose of this paper is to review what is known about adverse event disclosure policies and practice in the US and Canada, and to recommend steps to narrow the gaps between i) policy and practice and ii) physicians and health care organizations, and patients.

The 1999 report from the Institute of Medicine provided the first estimates of harm due to health care, estimating that as many as 98,000 patients a year in the US die related to adverse events.3 More recent estimates still remain in the 100,000 lives per year range. Autopsy studies of ICU patients have revealed up to 30% rate of unsuspected findings that would have changed treatment and improved outcome.4 An early study at a large teaching hospital found 3.13 medication errors per 1000 orders;5 more recent studies of adverse drug events in the ambulatory setting revealed a rate of 13.8 preventable adverse drug events per 1000 person-years.6-10 According to the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, wrong site surgery occurs as often as 40 times per week in the US. In the past 15 years, there has been a steady increase in awareness of patient safety problems, and increased recognition of the obligation of health care workers and health care organizations to inform patients about adverse events. However, there are disturbing gaps between patients and physicians in their attitudes about the communication of adverse events, and between disclosure policies and their implementation in practice.

Perhaps the most appropriate place to start is to ask: what do patients want and need? There has been an increase in recognition of the importance of patients’ perspectives on medical care, and a concomitant growth in research into patients’ views on medical errors and disclosure. Several studies suggest that patients are aware that safety is an issue in health care,11-13 and a surprisingly high percentage of the general population, (including physicians who might be considered competent to assess care) believe that they or a loved one has experienced a medical error.11,14 In one study of 11 countries, 11.2% of patients reported error.15 However, patients tend to define error more broadly than health care professionals. The patient definition may include communication problems, disrespect, lack of caring or compassion, and non-preventable adverse events as well as medical errors.16,17

Almost all patients would want to be told if an adverse event occurred in their care.14 However, as noted above, patients believe that physicians often don’t tell patients when an adverse event has occurred. In addition, patients sometimes suspect an error has occurred in their care, but don’t report these suspicions.17

Patients who have suffered adverse events report a range of reactions.12,18 Many feel frustrated, angry, anxious, depressed, or overwhelmed. Patients and family members may both feel guilt after an error, believing that there was something they could have done to prevent the error. Often the relationship with the provider is damaged, and trust is lost. Sometimes the relationship can be repaired, but in other cases the patient may change providers. A less frequent response, but a concerning one, is avoidance of healthcare providers in general. Conversely, some patients and family members report becoming more engaged and activated, seeking second opinions, researching their health conditions, asking more questions, and being more assertive in their interactions with their providers.

While health care workers tend to focus predominantly on the health outcomes and emotional consequences of an adverse event, such incidents may also have significant effects on other aspects of patients’ lives, such as school, work, family commitments and relationships. Additionally, adverse events often have financial consequences for patients and families, resulting for instance in co-payments for additional visits, lost wages, and costs of childcare. Obviously, when an adverse event results in a long-term disability or death, the costs can be overwhelming.

Studies of patients’ preferences for communication about adverse events fall into two major categories: studies of patients’ reactions to hypothetical situations, and studies of patients’ actual experiences with care. Findings from studies of patients’ reactions to hypothetical situations have concluded that whether and how a physician discloses an event affects how patients respond. For example, Mazor and colleagues randomly assigned patients to one of eight versions of a questionnaire which described an error and a physician-patient conversation about the error.14 The versions varied in terms of the error, the associated harm, and the level of disclosure. Full disclosure (wherein the hypothetical physician took responsibility for what had occurred, explained how the error had occurred, expressed regret, and conveyed a commitment to preventing recurrences) resulted in a more positive emotional response, greater satisfaction with the physician’s communication, greater trust, and lower likelihood of changing physicians. However, in these hypothetical situations, there was not a consistent effect on intent to seek legal advice; this intent was instead predicted by the nature of the error and the level of harm.14 Other studies yielded similar conclusions:12,19,20 full disclosure generally leads to a more positive patient response, but certain patient reactions (such as intent to seek legal advice) may be more affected by the event and the harm than by the level of disclosure.

Studies of patients’ actual experiences with disclosure of adverse events provide important insights that significantly extend the findings of these earlier studies, and also help to define what patients want after an event has occurred.17,18,21,22 First, patient interviews confirm that disclosure often does not occur. Second, nondisclosure does not prevent patients from suspecting that an error occurred. Patients – especially dissatisfied patients or patients in distress – may seek care elsewhere, obtain a second opinion, or seek advice from friends or family members who have medical expertise. In these ways and others, patients may obtain information that increases their suspicion. Third, patients who believe that they suffered from errors in care do not always voice their beliefs. Instead, they may suffer in silence which may prevent clinicians from correcting misperceptions, from mitigating harm or acting to prevent recurrence. Finally, this line of research has reinforced our understanding of the key elements of disclosure and how these affect how patients’ respond.18,21-23 The key elements are an explanation of the event, acknowledgement of responsibility as appropriate, sincere regret and apology, appreciation of how the event affected the patient and family, commitment to preventing recurrences, and evidence that learning occurred. The relative importance of each of these elements is likely to vary depending on the details of the event, its impact and the context. What is an ideal disclosure conversation in one situation may fall short in another. The elements of disclosure are discussed in further detail below.

Explanation

When patients believe something has gone wrong in their care, they want information. This typically includes an explanation of what happened, including how and why the event or error occurred. While patients understand that clinicians are human and make mistakes, they also trust that those providers they go to for care will do their best. When things go wrong, they want to know what happened.

Acknowledgement of responsibility

Patients respond positively when clinicians acknowledge that something has gone wrong, and assume appropriate responsibility. Clinicians who act in a defensive manner and attempt to minimize what has occurred are likely to be seen as trying to protect themselves from lawsuits. Such actions are unlikely to be protective, and are much more likely to further damage the relationship rather than help restore it.

Expression of sincere regret: apology

Patients respond positively to expressions of regret and apology, but only if these are perceived to be sincere. When a patient perceives that those involved are distressed by the event, he or she is more likely to accept the apology as sincere. Similarly, if a clinician actively and obviously seeks to rectify what has gone wrong, this is also likely to be considered evidence of caring. However, in the absence of an emotional response on the part of the clinician, the patient may perceive a spoken apology as empty, and the words I’m sorry may not be sufficient to restore trust.22

Sensitivity to the potentially broad-ranging effects of adverse events (including the emotional impact and life disruptions as well as the health effects) and expressions of empathy for the importance of these to the patient and family, can also help to convey caring, maintain trust and a strong provider-patient relationship.

Commitment to preventing recurrences

A cornerstone of the patient safety movement is the commitment to learning from adverse events and near-misses.3,24 Interestingly, patients and family members see the prevention of recurrences as top priority as well. Patients who suffer as the result of an adverse event resulting from errors overwhelmingly endorse the need to make sure that others do not suffer similarly. For clinicians and safety officers, such efforts may involve root cause analyses, discussions such as morbidity and mortality conferences, or other established procedures.25 Patients are typically not aware of the details of such efforts, nor are they typically involved (though when harm is serious, such details may be important to family members).26 But virtually all patients and family members want to know that the healthcare team is working to prevent recurrences. To patients, an important element of preventing recurrences is that those involved learned from the event. Thus, patients may expect both individual and system level efforts to improve the processes of care.

Financial reparations and legal action

Do compensation programs decrease litigation and improve disclosure of adverse events? Rick Boothman and colleagues at the University of Michigan instituted an open disclosure policy and early resolution program, with a subsequent decrease in claims from three million dollars to one million dollars.27 COPIC, the medical liability company of Colorado, has the most recognized private sector program, the 3Rs program.28 This program, since its inception, has provided over 3000 patients an average payment of $5400. This program encourages honest discussion between the physician and patient about the event that occurred. Both of these suggest that compensation may make disclosure less adversarial. In addition the low amount of payments in the COPIC data suggests that it is not always about a large amount of compensation.

While fear of litigation, reputational and financial loss are often cited as barriers to full disclosure at the clinician and organizational level, interviews with patients who believe that they have been harmed by clinician errors reveal that very few consider legal action even in the face of what they perceive to be significant harm.17,18,21,22,29

What do health professionals, especially physicians, believe should be done after an adverse event, and what do they want and need? Physicians are aware that the practice of medicine is fraught with peril, and worry about errors that may harm patients. They feel threatened by the possibility of being involved in a harmful event and resultant litigation. Thus, they are conflicted about how to handle such events. They think they should disclose most adverse events including errors, but have limited experience around disclosure and are not confident about their ability to have such discussions. They are also unsure if their colleagues will be supportive.12 They do tend to believe that deception is acceptable in some circumstances.30 They are often unaware of both policy and legal protections that are already in place regarding disclosure.

There is evidence of self-protective behaviour among physicians, who want to describe events in the most positive way possible.31,32 It appears that partial disclosure is common, which includes describing the event but not that it caused harm, implying that harm was caused by disease rather than care, describing the bad outcome but not the event, and not accepting appropriate responsibility or giving an apology. Paradoxically, they may take on responsibility for unavoidable outcomes or failures in the processes of care beyond their control.

Physicians hope that in the case of an adverse event, especially those related to error, they will get support from their colleagues and institutions. They would like support in carrying out disclosure discussions. Ideally, they would like understanding and forgiveness by patients. They want discussions to be kept as confidential as possible, but would also like changes to be made the delivery system to help prevent recurrences.

Disclosure in the USA

The problem

To Err is Human was the seminal report from the Institute of Medicine in 1999 that drew attention to the problem of medical errors and how physicians dealt with them.3 Prior to this time errors were hidden and often covered up.33 Paternalism prevailed and a defensive posture was common. There is now a consensus among medical organizations, ethicists and physicians that we should disclose all adverse events, including those resulting from error.34 The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics states that a physician must report an accident, injury or bad result stemming from his or her treatment; the American College of Physicians has a similar statement.35,36 Despite the universal endorsement of disclosing adverse events, studies still suggest disclosure of errors is not ubiquitous, occurring in only approximately 30% of cases.11,12,30,37,38

Attitudes toward disclosure

Recent articles have looked at the attitude of physicians-in-training toward disclosing errors. White et al.39 surveyed more than 1100 trainees, over 99% of whom agreed that disclosure should occur. However, only 34% had disclosed a serious error and only 33% had received training in disclosure. Barriers to disclosure included thinking the patient would not want to know about the error, would not understand the error, and fear of litigation. Varjavand et al.40 surveyed first year residents 9 years apart. They used two hypothetical scenarios that described one error with an adverse outcome and one without. In 1999-2000 29% would disclose an adverse outcome case and 38% would disclose on no harm cases. By 2008-2009 these numbers rose to 55% and 71%. Not surprisingly the biggest barrier was fear of litigation. A 2013 survey of 1891 physicians found that only two thirds completely agreed with disclosing serious medical errors to the patient and almost one fifth did not completely agree that doctors should never tell a patient something untrue.30 A total of 20% admitted they had not fully disclosed an error because of fear of litigation. Taken together, these and other studies suggest that physicians do not routinely disclose errors when they occur.

The biggest hurdle: fear

The literature is clear that there is still a gap between recommendations about disclosure of adverse events including errors and actual practice. There are many barriers to disclosure, with fear, and especially the fear of litigation, being one of the most prominent.41 Embarrassment and distress after adverse events are other frequently mentioned reasons,12 as are fear of reporting requirements to the National Practitioner Databank and fear of loss of license. There is also the possibility that disclosure will destroy the patients’ faith in the physician and the medical system in general, leading to avoidance of needed beneficial care.

In the litigious culture of the US there are incentives to bring suit, the most important being the chance of a large settlement. This presents a large hurdle to any clinician who might put themselves in harms way by disclosing an error. But is there a relationship between disclosure and litigation? This is controversial. It is certain that absence of disclosure may drive litigation in an effort to find out what happened,42 and studies suggest that when disclosure is made, awards might be lower.43 However, there are also cases in which litigation occurs subsequent to the revelation of an unsuspected error.44 There are a variety of disclosure and resolution programs in the United States that extend compensation to injured parties and families. In an interesting article, Murtaugh and colleagues surveyed lay people about their views on medical injuries, disclosure and apology.45 Respondents indicated they would appreciate full compensation offers after injury but this would not decrease their likelihood of seeking legal advice. Full compensation offers actually increased the likelihood that the disclosure and offer would be perceived as an effort to avoid litigation.

Over two thirds of the states have disclosure or apology laws. The majority protect the providers’ expression of sympathy from use in a patient’s lawsuit. However, there has been criticism of these laws.46 Critics suggest that these laws have structural weaknesses that actually discourage comprehensive apologies. These authors suggest that a more thorough or umbrella-like protection would stimulate more full disclosure and improve error communication.

Disclosure of harm in Canada

It is now recognized in Canada that improving patient safety is a priority. As a result of adverse events, it is estimated 8-24,000 adults are injured yearly in Canadian hospitals.47 Paediatric patients are also at risk.48 The Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) confirmed even higher rates of safety problems in home care in a review published in 2013.49

The CPSI, in an effort to standardize terminology with others across the world, promotes the use of the Patient Safety Incident terminology and definitions used in the International Classification of Patient Safety (ICPS) from the World Health Organization (WHO).

However the term adverse event is still used widely in Canada with the broad meaning of referring to harm from health care delivery. Harm therefore includes that resulting from the recognized inherent risks of investigations and treatments, from failures in the systems and processes of care and from provider performance and error. The provinces and territories may use different terms in their laws.

Disclosure of adverse events is considered an ethical and professional obligation of health professionals in Canada. For example, all of the provincial medical regulatory licensing authorities (Colleges), even those without formal policies, would expect disclosure. Although specific legislation may not exist in every jurisdiction, disclosure may be seen as a legal duty in all of the provinces and territories.

Accreditation Canada, the body that accredits and supports organizations in examining and improving the quality of care they provide to their patients, includes in its program of Required Organizational Practices that organizations must have a policy, including process and training, for disclosure of adverse events. The policy must include support mechanisms for patients, family, and care or service providers.

The CPSI brought together patient representatives and many professional healthcare groups from across Canada to develop the Canadian Disclosure Guidelines, published in 2008 with a further revision in 2011.50 These Guidelines are widely used in all of the Canadian provinces and territories to develop policy and approaches to disclosure. The Guidelines emphasize the importance of building a just culture in healthcare organizations to facilitate reporting and correction of vulnerabilities before patient harm occurs.51 Such a workplace culture emphasizes appropriate professional accountability. However, providers would not be held responsible for system failures over which they have little or no control.

The Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), the not-for-profit mutual defence association which has almost all Canadian physicians as members, published a companion booklet Communicating with your Patient about Harm: Disclosure of Adverse Events.52 This guide provides practical suggestions on how to meet the clinical, information, and emotional needs of patients and families who have experienced unexpected clinical outcomes. Early disclosure and on-going discussions are suggested, including advice on who should be involved, apology, and a summary checklist of the important steps.

The prevalence and impact of disclosure in Canada is not known. There is little formal research about the impact of the Canadian Disclosure Guidelines on disclosure. Most healthcare institutions would likely anecdotally report they have made progress in reporting and disclosing adverse events to patients over the last several years. Calls to the CMPA from physicians for advice about disclosure have increased.

The creation of a just culture and how to approach disclosure is now embedded in many Canadian patient safety education programs. Based on accreditation requirements, disclosure training in hospitals is relatively widespread, but generally less so in community practices. Although other training programs exist, the CMPA provides much of the training to physicians.

The Safety Competencies outline the expectations for training of health professionals in patient safety, including disclosure.53 Disclosure training is increasingly taught in medical schools and residency training. The existing CanMEDS framework used to guide physician training in Canada are currently being revised to explicitly incorporate The Safety Competencies and will be published in 2015.

Apology legislation is in place in 8 of 10 provinces and 2 of 3 territories. The legislation protects an apology from being used in civil litigation and, depending on the wording, in some other investigative forums. It typically provides that an apology does not constitute an admission of fault or liability. This legislative protection has not been challenged in court to date. Early offers of compensation are generally not linked to disclosure in Canada, as negligence has not been proven. The Canadian courts have the responsibility to make such determinations.

There is increasing recognition that providers involved in adverse events may also have clinical, emotional, and information needs. The CMPA publishes advice on coping in the CMPA Good Practices Guide.

The second victim

The problem of the second victim is a close corollary of disclosure. A second victim is a health care provider involved in an adverse event and who is also traumatized.54 Some providers may find a disclosure discussion healing but others may suffer after a disclosure discussion and an error. The initial reaction is consistent with acute stress disorder, with shock, anxiety, depressive symptoms, social withdrawal and agitation, compounded by feelings of shame, guilt and self-doubt.55 Although these symptoms typically last for days to weeks, a few individuals go on to have symptoms similar to those of post traumatic stress disorder, including flashbacks, avoidance of associated situations, and sleep disturbance. Health care workers can be impaired by both short and long terms symptoms.56-59 Some leave their professions altogether, and a few even commit suicide.60

Psychological trauma can be induced by multiple factors, beginning with the event itself.61,62 The responses of peers, which can be critical or otherwise hurtful, can add to the trauma.63,64 The subsequent investigation can re-open old wounds, particularly if conducted in an insensitive manner.61 Scott describes enduring the inquisition as an expected stage in the second victim’s reaction.65 Finally, malpractice litigation is well known to be traumatic for all parties involved.66

The prevalence estimates of second victims range from 10-50%.63,65,67,68 Requiring disclosure of adverse events to patients, in turn, requires the disclosing health care workers to confront and accept responsibility for their own errors which may permit absolution but increase distress.69,70 Awareness and consideration of the problem of second victims, and supporting clinicians after adverse events is a necessary component of systematic and comprehensive approach to handling adverse events.71

Proposed solutions

This discussion demonstrates the need to address the gaps between patient and professional attitudes, and between disclosure policy and actual practice. Delivering health care is an inherently risky enterprise. A number of approaches have been suggested including comprehensive risk mitigation.72,73

Even when errors are conceptualized as attributable to system-level faults or breakdowns, the responsibility for recognizing and disclosing errors falls to individuals. In spite of the prevalence of policies supporting disclosure and transparency when errors occur, individual providers continue to face substantial barriers to conducting effective disclosure conversations. These include: i) fear of the financial and legal consequences of disclosure. So long as care providers worry about this, they can be expected to be guarded about their role in adverse events, and the perceived risks of disclosure. ii) Loss of face and emotional distress; becoming the second victim of an event. iii) Attitudes, including the belief that disclosure is not necessary or appropriate; sometimes coupled with the belief that disclosure would not benefit the patient. iv) Skill deficits, including lack of training or practice in effective disclosure. v) Limited role modelling of disclosure during medical school, residency, and practice and the consequent perception that disclosure is not the norm. vi) Lack of an institutional culture and norms supporting disclosure, (a just culture of patient safety) manifesting as lack of support from colleagues and tacit acceptance of nondisclosure.

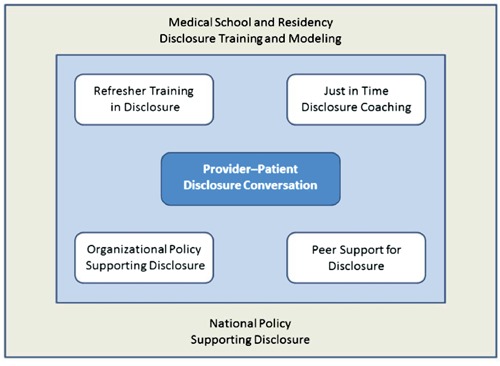

The presence of these multiple barriers suggests that a comprehensive solution, directed at multiple levels of the healthcare system is needed (Figure 1). While providers may find themselves alone with the patient and family members as they disclose a medical error, they need support from all levels of the healthcare system to have the conversations consistently and effectively.

Figure 1.

Multiple levels of the healthcare system.

Policy solutions are a key ingredient in supporting and increasing disclosure. To be most effective, policies should include detailed guidance and instructions for providers related to disclosure of adverse events, such as those created by the CMPA at a state or national level.52 Although national guidance is not available in the US, several influential groups have published and disseminated detailed recommendations.73-77 While critical, national policies are unlikely to be sufficient. Local policies, based in part on these guidelines, need to reiterate the importance of disclosure, and customize guidance and expectations to the specific institutional context. These policies in turn provide the foundation for educational and training efforts. At the national level, training in the communication skills needed for effective disclosure should be incorporated into medical school, residency and all health care professional education, and preceptors need to model these skills. At the local practice level, continuing efforts are required both to convey the message that disclosure is expected and supported, and to provide opportunities to refresh and practice disclosure skills. Such refresher training is needed because most providers will have few disclosure conversations over the course of their careers. For this reason, additional support, such just-in-time in-person coaching (e.g., from on-call Risk Managers or other specially trained staff) or on-line support of disclosure (e.g., giving standard operating procedures and pointers) should be offered to providers to help them prepare for these infrequent conversations. Finally, patients should be engaged, by being informed about institutional policies and the expectation of openness after adverse events.

While policy and educational efforts are necessary to increasing the prevalence and effectiveness of disclosure, the continuing gap between policy recommendations and actual practice makes clear that existing policies are not being implemented. It is our belief that the most intractable barriers are emotional, cultural and attitudinal. Providers continue to fear the consequences of disclosure. Cultural norms – beginning with the hidden curriculum that communicates a norm of guardedness and self-protection in medical school and residency, continuing into practice – militate against disclosure. These attitudes together continue to reinforce attitudes that disclosure is both dangerous and unnecessary. What additional changes are needed to improve the health care cultural norms around handling harm from health care delivery, and the personal handling of failure and medical errors?

We believe that the translating-evidence-into-practice (TRIP) framework may provide useful insights.78 This approach begins with envisioning the problem on the system level, and engaging local interdisciplinary teams to carry out the improvements needed. We believe that engagement of local teams is the necessary first step in changing local culture and norms. These local teams would begin by summarizing the evidence on best practices relating to handling adverse events and error. They would then review and examine these best practices in order to identify local barriers to implementation. The TRIP framework incorporates the expectation that additional intervention, including changes in policy, may be needed to overcome these barriers. A component of this examination might be to take a positive deviance approach, and study those local providers who actually do disclose to identify the situational, personal, and organizational factors that support this behaviour. These effective providers could serve as coaches as well as supporters of the local efforts.

Another foundational step in the TRIP framework is to obtain baseline measurements of performance, in terms of policies and structures that are in place and awareness by provider and patients of those structures; provider attitudes (e.g., using safety attitude surveys); actual performance including conducting disclosure (e.g., using actual testing or certification of satisfactory completion of training), and outcomes such as patient and provider satisfaction with the actual discussions. These measures should be put in place at every level of the health care system. Assuring that all known adverse events, including those from errors are disclosed successfully would require increased engagement of health care leaders and workers to reinforce motivation and to change the local culture and norms. Health care workers at all levels of the local system need to be educated about the appropriate handling of adverse events, and the selected elements of the program need to be implemented, followed finally by evaluation of the results.

Conclusions

Thought leaders in both the US and Canada have explored the issue of disclosing adverse events to patients, and there has been a tentative start toward open disclosure in both countries. In some ways, Canada has fewer hurdles to successful implementation. It has a single major medico-legal defence organization for physicians, much more comprehensive health care for those injured, and a significantly less litigious society. In the US there is an array of litigation defence companies with different philosophies on whether disclosure should even occur. The lack of universal health coverage means that when one is injured, continuing and on-going expenses may be a significant driver in the decision to sue. Nevertheless both countries have supported the policy goal of full disclosure with laws, legal mandates, and training and support of physicians and other health professionals who do disclose errors. There is little literature in Canada about how often disclosure occurs, but in the US it is evident that it is not occurring uniformly. And even when it does occur it may still be done in an incomplete or problematic fashion. We feel that a comprehensive, system wide approach is needed, with legal, health system and local institutional support. At the local level, implementation will require formation of teams, training, measurement, and identification of local barriers to achieve the ultimate goal of universal disclosure of adverse events.

References

- 1.Patient Safety Net Glossary. Available from:http://psnet.ahrq.gov/glossary.aspx Accessed on: October, 2013

- 2.World Health Organization. Conceptual framework for the international classification of patient safety. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available from:http://www.who.int/patientsafety/ implementation/taxonomy/icps_technical_report_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M.To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press; 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Combes A, Mokhtari M, Couvelard A, et al. Clinical and autopsy diagnoses in the intensive care unit: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:389-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995;274:35-43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf 2013;9:122-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar U, López A, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Adverse drug events in U.S. adult ambulatory medical care. Health Serv Res 2011;46:1517-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson DR. Adverse events in hospitals: national incidence among medicare beneficiaries. Report No. OEI-06-09-00090. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. Global trigger tool shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:581-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1933-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, et al. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA 2003;289:1001-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser Family Foundation/Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality/Harvard School of Public Health. National survey on consumers’ experiences with patient safety and quality information. November, 2004. Available from:http://kaiserfamily foundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/national-survey-on-consumers-experiences-with-patient-safety-and-quality-information-survey-summary-and-chartpack.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, et al. Health plan members’ views about disclosure of medical errors. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:409-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwappach DL. Risk factors for patient-reported medical errors in eleven countries. Health Expect 2012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Gallagher TH, et al. Patients’ concerns about medical errors during hospitalization. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:5-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Towards patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1784-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazor KM, Goff SL, Dodd K, Alper EJ. Understanding patients’ perceptions of medical errors. J Commun Health Care 2009; 2:34-46 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazor KM, Reed G, Yood RA, et al. Disclosure of medical errors: what factors influence how patients respond? J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:704-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu AW, Huang IC, Stokes S, Pronovost PJ. Disclosing medical errors to patients: it’s not what you say, it’s what they hear. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazor KM, Goff SL, Dodd KS, et al. Parents’ perceptions of medical errors. J Patient Saf 2010;6:102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazor KM, Greene SM, Roblin D, et al. More than words: patients’ views on apology and disclosure when things go wrong in cancer care. Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:341-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu AW, Cavanaugh TA, McPhee SJ, et al. To tell the truth: ethical and practical issues in disclosing medical mistakes to patients. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:770-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu AW, Marks CM. Close calls in patient safety: should we be paying closer attention? CMAJ. 2013 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130014. Apr 16. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu AW, Lipshutz AK, Pronovost PJ. Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine. JAMA 2008;299:685-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millman EA, Pronovost PJ, Makary MA, Wu AW. Patient-assisted incident reporting: including the patient in patient safety. J Patient Saf 2011;7:106-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boothman RC, Blackwell AC, Campbell DA, Jr, et al. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law 2009;2:125-59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher TH, Studdert D, Levinson W. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2713-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraman SS, Hamm G. Risk management: extreme honesty may be the best policy. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:963-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, DesRoches CM, et al. Survey shows that at least some physicians are not always open or honest with patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:383-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallagher TH, Garbutt JM, Waterman AD, et al. Choosing your words carefully: how physicians would disclose harmful medical errors to patients. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1585-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loren DJ, Klein EJ, Garbutt J, et al. Medical error disclosure among pediatricians: choosing carefully what we might say to parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:922-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilfiker D. Facing our mistakes. N Engl J Med 1984;310:118-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Policy and Procedures. Revisions to Joint Commission standards in support of patient safety and medical/health care error reduction. Effective: July 1, 2001. Available from:https://www.premierinc.com/safety/topics/patient_safety/downloads/12_JCAHO_strds_05-01-01.doc [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Medical Association. American Medical Association code of medical ethics. 2013. Available from:http://www.amaassn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics.page? [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder L. American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians Ethics Manual: sixth edition. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:73-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Disclosing medical errors to patients: attitudes and practices of physicians and trainees. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:988-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Garbutt JM, et al. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudes and experiences regarding disclosing errors to patients. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1605-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White AA, Gallagher TH, Krauss MJ, et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med 2008;83:250-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varjavand N, Nair S, Gracely E. A call to address the curricular provision of emotional support in the event of medical errors and adverse events. Med Educ 2012;46:1149-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibson R. Wall of silence: the untold story of the medical mistakes that kill and injure millions of Americans. New York: Lifetime Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 42.May ML, Stengel DB. Who sues their doctors? How patients handle medical grievances. Law, Soc Rev 1990;24:105-20 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popp PL. How will disclosure affect future litigation? J Healthc Risk Manag 2003;23:5-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med 2004;350:283-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murtagh L, Gallagher TH, Andrew P, Mello MM. Disclosure-and-resolution programs that include generous compensation offers may prompt a complex patient response. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2681-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mastroianni AC, Mello MM, Sommer S, et al. The flaws in state apology and disclosure laws dilute their intended impact on malpractice suits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1611-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matlow AG, Baker GR, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Paediatric Adverse Events study. CMAJ 2012;184:E709-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Safety at home: a Pan-Canadian home care safety study. Available from:http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/English/research/commissionedResearch/SafetyatHome/Documents/Safety At Home Care.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Canadian disclosure guidelines: being open with patients and families. 2011. Available from:http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/English/toolsResources/disclosure/Documents/CPSI%20Canadian%20Disclosure%20Guidelines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marx D. Patient safety and the just culture: a primer for health care executives. New York: Columbia University; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canadian Medical Protective Association. Communicating with your patient about harm: disclosure of adverse events. 2008. Available from:https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/cmpapd04/docs/resource_files/ml_guides/disclosure/introduction/index-e.html Accessed on: October 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frank JR, Brien S.eds.The safety competencies: enhancing patient safety across the health professions. Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2008. Available from:http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/English/toolsResources/safetyCompetencies/Documents/Safety%20Competencies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. Often the doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320:726e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waterman AD, Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR. The natural history of recovery for the health care provider second victim after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:325-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwappach DL, Boluarte TA. The emotional impact of medical error involvement on physicians: a call for leadership and organizational accountability. Swiss Med Wkly 2009;139:9e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:467-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newman MC. The emotional impact of mistakes on family physicians. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:71e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engel KG, Rosenthal M, Sutcliffe KM. Residents’ responses to medical error: coping, learning, and change. Acad Med 2006;81:86e93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg 2011;146:54-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu AW, Steckelberg RC. Medical error, incident investigation and the second victim: doing better but feeling worse? BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:267-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seys D, Wu AW, Van Gerven E, et al. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof 2013;36:135-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edrees HH, Paine LA, Feroli ER, Wu AW. Health care workers as second victims of medical errors. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2011;121:101-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aasland OG, Forde R. Impact of feeling responsible for adverse events on doctors’ personal and professional lives: the importance of being open to criticism from colleagues. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:13-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, et al. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider second victim after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:325-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vincent CA. Fallibility, uncertainty, and the impact of mistakes and litigation. Firth-Cozens J, Payne R. Stress in health professionals. London: John Wiley; 1999. 63-76 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lander LI, Connor JA, Shah RK, et al. Otolaryngologists’ responses to errors and adverse events. Laryngoscope 2006;116:1114-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolf ZR, Serembus JF, Smetzer J, et al. Responses and concerns of healthcare providers to medication errors. Clin Nurse Spec 2000;14:278-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu AW, Folkman S, McPhee SJ, Lo B. Do house officers learn from their mistakes? JAMA 1991;265:2089-94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu AW, Folkman S, McPhee SJ, Lo B. How house officers cope with their mistakes. West J Med 1993;159:565-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Conway JB, Weingart SN. Leadership: assuring respect and compassion to clinicians involved in medical error. Swiss Med Wkly 2009;139:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDonald TB, Helmchen LA, Smith KM, et al. Responding to patient safety incidents: the seven pillars. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Conway J, Federico F, Stewart K, Campbell M. Respectful management of serious clinical adverse events. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2010. Available from:http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/RespectfulManagementSeriousClinicalAEs WhitePaper.aspxAccessed on: August, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 74.American Society of Healthcare Risk Management. Perspective on disclosure of unanticipated adverse outcome information. Chicago, IL 2001. Available from:https://www.premierinc.com/safety/topics/patient_safety/downloads/ASHRM_disclosure_05-01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 75.National Quality Forum. Safe practices for better healthcare. National Quality Forum. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 76.ACOG Committee on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee on Professional Liability Number 520, March 2012. Available from:http://www.acog.org/Resources%20And%20Publications/Committee%20Opinions/Committee%20on%20Patient%20Safety%20and%20Quality%20Improvement/Disclosure%20an d%20Discussion%20of%20Adverse%20Events.aspx

- 77.Health Lawyers Recommend Guidelines for Medical Error Disclosure. Guidon Performance Solutions. July 12, 2012. Available from:http://www.guidonps.com/industry-news/health-lawyers-recommend-guidelines-for-medical-error-disclosure/ [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ 2008;337:a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]