Abstract

Introduction:

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by bilateral white striations or plaques on the buccal mucosa, tongue or gingiva that has a multifactorial etiology, where the psychogenic factors seem to play an important role.

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to determine the existing relation between the OLP and psychological alterations of the patient, such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

Materials and Methods:

Hospital anxiety and depression scale was applied for psychometric analysis.

Results:

The study indicates a definitive relationship between a stressful life event and onset and progression of OLP.

Conclusion:

Stress management and bereavement counseling should be a part of management protocol of OLP.

Keywords: Anxiety, hospital anxiety and depression scale, lichen planus, psychosomatic, stress

Introduction

Lichen planus is a common dermatological disorder, which may affect the skin and oral mucosa. The condition was described for the first time by Erasmus Wilson in 1869 who characterized the patients as anxious, high strung, and sensitive with a tendency to worry excessively and with periods of undue emotional stress.[1]

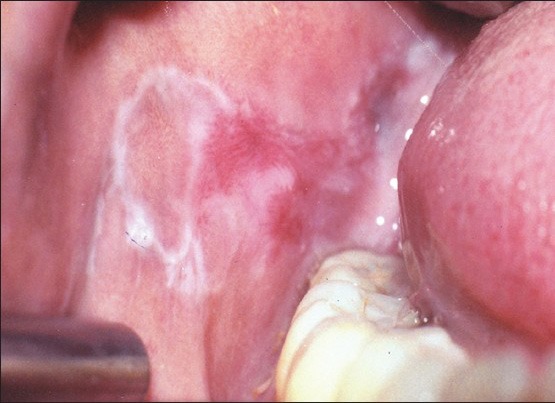

Oral lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by bilateral white striations or plaques on the buccal mucosa, tongue or gingival [Figures 1 and 2]. It is found commonly in adults (50-55 years of age) and predominantly affects women usually by a 1.4:1 ratio over men.[2] OLP has varied clinical presentations, with the reticular, erosive, and atrophic types being the most commonly reported.[3] In the last few years, significant advances have been made in understanding the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. OLP has been reported to be associated with different medical conditions such as diabetes, hepatitis C infection, and liver disease.[2,3]

Figure 1.

Reticular and erosive oral lichen planus on the buccal mucosa

Figure 2.

Extensive reticular oral lichen planus lesions

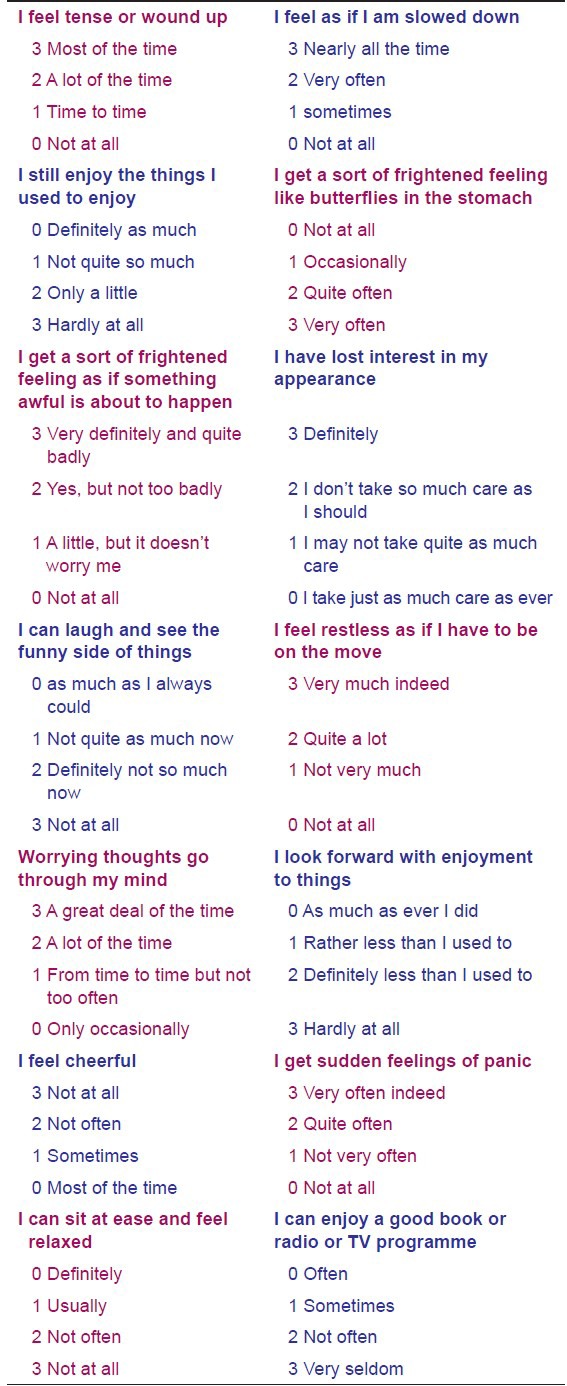

Although, the condition is often referred to as stress associated ulcerations of the oral mucosa and research to date hints on a psychosomatic component in the etiology and progression of OLP, very little documentation has been presented to substantiate this widely held assumption.[1,4,5,6,7,8] Recent studies using instruments to assess the stress in these patients have resulted in conflicting reports [Table 1].

Table 1.

Studies evaluating stress in oral lichen planus patients

In spite of a few anecdotal documentations, it is still contentious as the field of research is complex and its integration in the domain of oral biology and medicine is still at its initial stages.

According to World Health Organization, health is defined as a complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity. An inference of this definition may be the proposal that there is a need to consider multiple factors in the appraisal of health outcomes.[8]

The study was designed with the rationale to establish an association between stress and OLP and investigate psychological factors in a group of patients with OLP using validated psychometric tests.

Materials and Methods

The sample comprised of 49 patients who were seen in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology between August 2009 and September 2011 and who had been diagnosed with OLP. OLP diagnosis was made through a composite of accepted clinical and histopathological criterion. Only patients with firm clinical and histological diagnosis of OLP were considered. Lichenoid reactions and OLP with dysplastic features were excluded from the present study.

Detailed information about the age, sex, family, and social history, history of medication, and history of stress was obtained. Discomfort was evaluated according to self-reported pain estimates and graded as none/slight/moderate/severe.

Controls included a total of 49 age and sex matched patients who attended the outpatient clinic of Department of Oral Medicine for routine dental check-up. None of them had any history of disease or metabolic disorder.

All the patients including controls underwent psychometric analysis. Permission from the hospital ethics committee and informed written consent were obtained from all the subjects.

Psychometric test

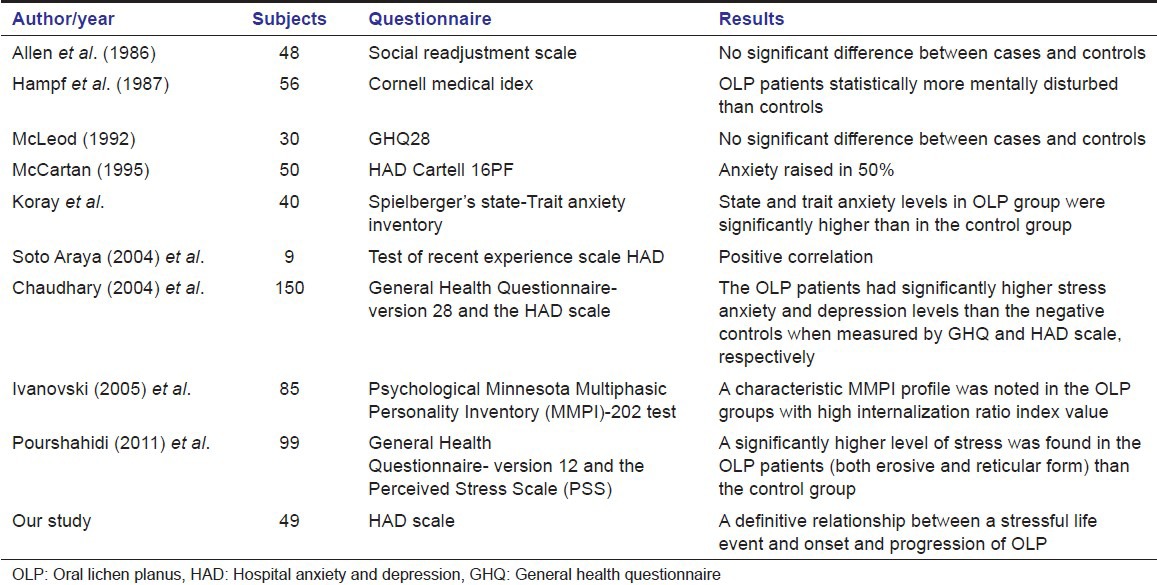

Hospital anxiety and depression (HAD) scale was applied [Table 2]. This scale was developed by Snaith and Zigmond and was designed for assessment of anxiety and depression in hospital outpatients in an adult population. It is a sensitive screening tool comprising of a quick and simple questionnaire. The total number of questions were 14 out of which 7 (even questions; scores in blue) reflecting anxiety and the other 7 (odd questions; scores in red) reflecting depression.

Table 2.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Each question is rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety or depression. The maximum score on either subscale is 21, with scores of 8-10 representative of “borderline” psychological morbidity and scores of 11 or more indicative of a significant “case” of depression or anxiety. The questionnaire was self-administered. The Punjabi version of HAD scale was used for non-English speaking patients to participate in the present study. Total time given to each patient was 2-5 min.

Before administration of the scale, certain points were kept in mind. They were assured about the benign nature of the lesion. The test was applied only after one follow-up visit had taken place (in order to acquaint them with the environment).

Statistics

As the data from HAD scale was not normally distributed, statistical analysis was carried out using Kruskar-Wallis test. Probability value P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic profile

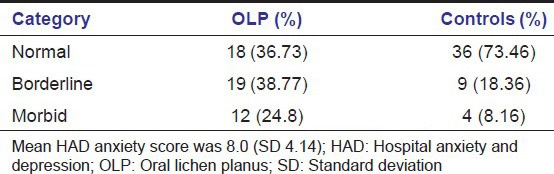

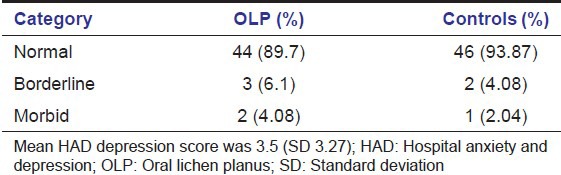

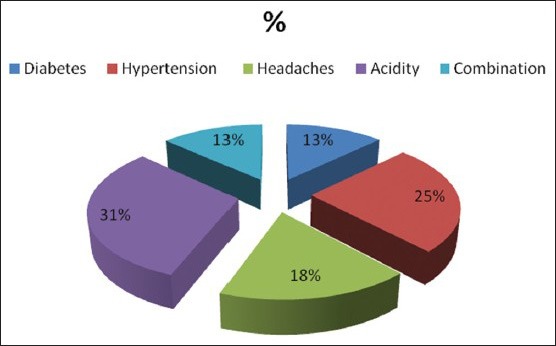

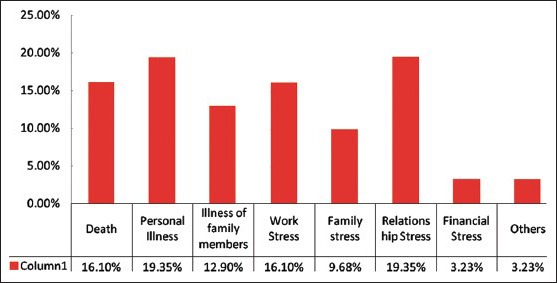

Out of the 49 patients there were 23 males (46.9%) and 26 females (53.6%). Buccal mucosa was the most common site. The mean age was 56.2 years and range was 35-67 years. Stressful life event was noted in 31 (63.2%) of the subjects at the time of OLP onset. No stressful life event was noted in 18 (36.73%) of the subjects at the time of OLP onset. 63% of the patients perceived stress with onset and waxing/waning of the OLP lesions. Mean HAD anxiety score was 8.0 (standard deviation [SD] 4.14) [Table 3]. Mean HAD depression score was 3.5 (SD 3.27) [Table 4]. Stress related general disease states such as hypertension, diabetes, headaches, acidity problems, and a combination of these disease states are observed in Figure 3. When asked about major life-style change that occurred before onset of OLP the subjects had experience considerable life stress, loss of job, and loved ones, relationship, and health stress [Figure 4].

Table 3.

Hospital anxiety and depression anxiety categories

Table 4.

Hospital anxiety and depression categories

Figure 3.

Stress related general disease states in oral lichen planus patients

Figure 4.

Relationship of stressful life event and oral lichen planus

Discussion

OLP affects 1-2% of the adult population and is the most common non-infectious oral mucosal disease.[1] It affects women more than men (1.4:1) and occurs predominantly in adults over 40. Lesions are typically bilateral and often appear as a mixture of clinical subtypes.[2,3] In his original description of cutaneous and OLP; Wilson described anxiety, hysteria, and depression as etiological factors. Approximately, two-third of OLP patients report oral discomfort. Most cases of symptomatic OLP are associated with atrophic (erythematous) or erosive (ulcerative) lesions. Symptoms vary from mucosal sensitivity to continuous debilitating pain.[9] OLP lesions usually persist for many years with periods of exacerbation and quiescence. During the periods of exacerbation, erythema or ulceration increases with increased pain and sensitivity which decreases during periods of quiescence. Patients are often unaware of quiescent OLP that presents typically as faint white striations, papules or plaques. Exacerbation of OLP has been linked to periods of psychological stress and anxiety.[10]

Stress can be defined as the biological reaction to any adverse internal/external stimulus, physical, mental or emotional, that tends to disturb the organisms homeostasis. Inadequate compensating reactions may lead to disorder. In the recent years, the injurious effects of stress have received attention.[8,11] Stress has shown to manifest as fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, tachycardia anxiety and cynicism.[12]

This study was conducted to ascertain an association between stress and OLP lesions. The results of this study suggest a high level of anxiety in patients with OLP as compared to the controls. Around 63.2% of patients suffered from borderline or morbid anxiety. The results are in accordance with McCartan et al., (1995), Vallejo et al., (2001),[5] Soto Araya et al., (2004)[1] and not in accordance with Allen et al., (1986)[9] and Rodstrom (2001).[6] In the present study, HAD Scale was used for identifying and quantifying the two most common forms of psychological disturbances in patients, namely anxiety and depression.[13] This scale was developed by Snaith and Zigmond for assessment of anxiety and depression in hospital outpatients in an adult population. It is a sensitive screening tool comprising of a quick and simple questionnaire. The results with these questionnaires confirmed the presence of anxiety and depression in the OLP patients. The strengths of the scale include brevity and widely accepted use. It is simple to use and is self-administered. It is less focused on somatic symptoms and focuses on two aspects of emotional disorder which are clinically considered to be most relevant, i.e., anxiety and depression.[13] However, this test has certain limitations, which include that it is only valid for screening purposes and definitive diagnosis must rest on the process of clinical examination. Caution must be exercised in illiterate and patients with ill vision who are ashamed of their defect. In these cases, wording of items and possible responses should be attempted. The Punjabi version of HAD scale was used for non-English speaking patients to participate in the present study.[14]

However, our study had certain pitfalls. Chronic discomfort that can affect patients with OLP can be itself being a stress factor. The psychological questionnaire relied a lot on subjective analysis of stress. Objective stress analysis was not performed. Interventional study to judge whether stress management results in waning of OLP lesions is still underway.

Vocalization and the process of bringing out into the consciousness the troubling issues and realization that a caring individual is lending a concerned ear can often alleviate the patient's concerns, tensions, anxiety, and stress.[2] We can improve the quality of care provided to patients through use of such measures and by referring patients with psychological risk factors to a psychologist or psychiatrist skilled in assessing and treating such patients. The reasons of referral should be explained carefully to the patients in order to reduce possible defensiveness and increase receptivity.

Summary and Conclusion

The major findings of this study clearly indicate that patients perceived a relationship between stressful life events and onset and progression of OLP. Stress management and bereavement counseling should be a part of management protocol of OLP. Future research should aim at assessing coping style and the effects of stress management upon the outcome of the lesion and record the general personality traits of OLP patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Soto Araya M, Rojas Alcayaga G, Esguep A. Association between psychological disorders and the presence of oral lichen planus, burning mouth syndrome and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Med Oral. 2004;9:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chainani-Wu N, Silverman S, Jr, Lozada-Nur F, Mayer P, Watson JJ. Oral lichen planus: Patient profile, disease progression and treatment responses. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:901–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M, et al. Update on oral lichen planus: Etiopathogenesis and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:86–122. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koray M, Dülger O, Ak G, Horasanli S, Uçok A, Tanyeri H, et al. The evaluation of anxiety and salivary cortisol levels in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2003;9:298–301. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallejo MJ, Huerta G, Cerero R, Seoane JM. Anxiety and depression as risk factors for oral lichen planus. Dermatology. 2001;203:303–7. doi: 10.1159/000051777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rödström PO, Jontell M, Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Lindstedt G. Erosive oral lichen planus and salivary cortisol. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:257–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiappelli F, Cajulis OS. Psychobiologic views on stress-related oral ulcers. Quintessence Int. 2004;35:223–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampf BG, Malmström MJ, Aalberg VA, Hannula JA, Vikkula J. Psychiatric disturbance in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:429–32. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen CM, Beck FM, Rossie KM, Kaul TJ. Relation of stress and anxiety to oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:44–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanovski K, Nakova M, Warburton G, Pesevska S, Filipovska A, Nares S, et al. Psychological profile in oral lichen planus. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1034–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pourshahidi S, Ebrahimi H, Andisheh TA. Evaluation of the relationship between oral lichen planus and stress. Shiraz Univ Dent J. 2011;12:43–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhary S. Psychosocial stressors in oral lichen planus. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:192–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sajatoric M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi Comp. Inc; 2001. Anxiety rating scales. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane DA, Jajoo J, Taylor RS, Lip GY, Jolly K Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation (BRUM) Steering Committee. Cross-cultural adaptation into Punjabi of the English version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]