Abstract

Motivation: Next-generation sequencing technologies produce unprecedented amounts of data, leading to completely new research fields. One of these is metagenomics, the study of large-size DNA samples containing a multitude of diverse organisms. A key problem in metagenomics is to functionally and taxonomically classify the sequenced DNA, to which end the well-known BLAST program is usually used. But BLAST has dramatic resource requirements at metagenomic scales of data, imposing a high financial or technical burden on the researcher. Multiple attempts have been made to overcome these limitations and present a viable alternative to BLAST.

Results: In this work we present Lambda, our own alternative for BLAST in the context of sequence classification. In our tests, Lambda often outperforms the best tools at reproducing BLAST’s results and is the fastest compared with the current state of the art at comparable levels of sensitivity.

Availability and implementation: Lambda was implemented in the SeqAn open-source C++ library for sequence analysis and is publicly available for download at http://www.seqan.de/projects/lambda.

Contact: hannes.hauswedell@fu-berlin.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Next-generation sequencing has opened the door to a multitude of possible research fields, among them metagenomics. In metagenomic projects, millions or billions of DNA or cDNA reads are collected in a single experiment. Usually it is attempted to either assemble the genomes of the organisms contained in the sample or to determine its taxonomic content, i.e. conduct a sequence classification. This means assigning a read to a known, usually protein-coding and annotated, subject sequence to identify the encoded function, the organisms present in the sample or identify the closest relative. Bazinet and Cummings (2012) give an overview of the various programs that have been developed to address this problem. Of the approaches they compare, 11 of 14 use BLAST in their pipeline. Hence, BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) can be seen as the de facto standard used for trying to solve this problem. Bazinet and Cummings (2012) also note in their study that ‘[the] BLAST step completely dominates the runtime for alignment-based methods’. For the two programs with the highest precision in their comparison, CARMA (Gerlach and Stoye, 2011; Krause et al., 2008) and MEGAN (Huson et al., 2007), the BLAST step actually made up 96.40 and 99.97% of the runtime. Another metagenomic study (Mackelprang et al., 2011) states that 800 000 CPU hours at a supercomputer center were required to conduct the study. Hence, since some time there is an effort to replace the BLAST suite by algorithms and tools that are much faster while not sacrificing too much accuracy. That means the tools aim at finding the same alignment locations as BLAST and possibly an alignment of similar quality (expressed by bit score).

1.1 Previous work

Some tools sought to replace BLAST, with varying success, among them BLAT (Kent, 2002) and the more recent releases of UBlast (Edgar, 2010), RAPSearch2 (Ye et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2012), and PAUDA (Huson and Xie, 2013). The latter tools all claim to be magnitudes faster than BLAST and at least notably faster than BLAT—at the expense of some degrees of sensitivity. All contain specific algorithmic optimizations for searches against protein databases, (BLAST and BLAT are more general purpose tools, which are optimized for pure DNA searches as well) most notably the use of reduced alphabets, a technique that we also use in Lambda. While UBlast and RAPSearch seem to be designed as general replacements for BLAST modes that contain protein searches, PAUDA is more specifically designed for metagenomic tasks.

There are further tools with similar intentions, among them SANS (Koskinen and Holm, 2012). These were not included in our comparison because the lack of e-value statistics makes it difficult to assess the significance of the results and to compare them with those of other programs.

1.2 Our contribution

Lambda adapts a new approach inspired by the read mapper Masai (Siragusa et al., 2013). The approach is based on the concepts of double indexing and multiple backtracking, i.e. Lambda uses a Radix tree of the queries’ seeds (non-overlapping k-mers of the reads) to search in a suffix array index built over the subject sequences. This method is unique among the programs compared.

The sequences in the query DNA strings are translated into amino acid sequences and converted using an alphabet reduction. Lambda supports several alphabet reductions, the default is the commonly used Murphy10 reduction (Murphy et al., 2000). Lambda offers three modes (fast, default and sensitive) in each of which it beats the competitors in speed while having similar sensitivity. Furthermore, it offers a sensitive version of the x-drop algorithm for seed-extension, which results in highly accurate alignments compared with the BLAST gold standard and our competitors. Although Lambda was designed for the purpose of replacing BlastX and we will concentrate on this aspect in the following, it also supports all other versions of the BLAST suite (BlastP, BlastN, TBlastN and TBlastX). In addition, it supports the most commonly used BLAST formats (tabular and pairwise) and hence can easily replace BLAST in established pipelines. Finally, Lambda is part of the tool suite of the SeqAn library (Döring et al., 2008) for efficient biological sequence analysis (e.g. Emde et al., 2010; Kehr et al., 2011; Siragusa et al., 2013; Weese et al., 2009, 2012) and is multithreaded to offer the advantage to run in parallel on modern multicore architectures.

In the following we will elaborate on the details of the Lambda algorithm and implementation in Section 2 and show in Section 3 how Lambda performs on two recently discussed datasets (Sargasso Sea and Bovine Gut) in comparison with the state-of-the-art methods Rapsearch2, UBlast, Pauda and of course BLAST.

2 METHODS AND IMPLEMENTATION

The general work flow of Lambda (in BlastX mode) can be summarized as follows:

In a first step, the query DNA sequences are translated into amino acid sequences, which are then converted into sequences of a reduced alphabet. The sequences are then used to create a query search trie [A trie (prefix tree) in the context of this article describes a special tree storing for each prefix of a text its location in the text]. Due to the alphabet reduction (which captures the amino acid similarities) the trie can be used to search for (edit-distanced) matches in a pre-computed database index; without alphabet reductions more expensive substitution matrices would have to be used. In a last step, the seeds are extended and verified.

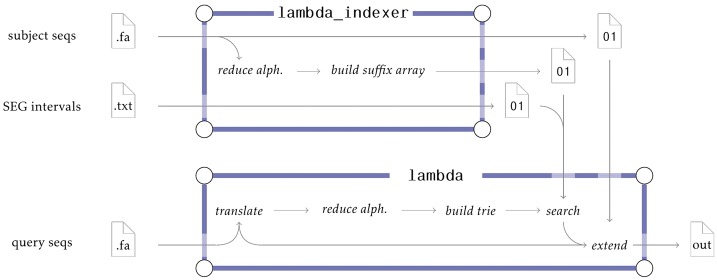

In addition to the lambda binary performing the tasks above, Lambda also includes a second binary, lambda_indexer, for pre-processing the database sequences. The entire pipeline is displayed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Pipeline of Lambda (BlastX-mode). The lambda_indexer takes as input a file with the subject sequences and optionally an interval file computed by seqmasker to create the index for seed identification. The query sequences are translated from DNA to amino acid alphabet, reduced and then converted into a search trie. Afterwards, the search trie is used together with the pre-computed index to find candidate regions, which are then extended and verified

2.1 Translation

Most metagenomic studies that are interested in the functional analysis and identification of the sample want to search protein databases with genomic or transcriptomic sequences, i.e. sequences in DNA or RNA alphabet. In this case, the sequences need to be translated into amino acid space to permit the comparison. As part of this work, an efficient implementation for six-frame translation was added to the SeqAn library (Döring et al., 2008) that makes use of OpenMP and allows to translate 14 million reads of ∼100 bp length, with six frames in 2.3 s.

In contrast to other applications, Lambda offers all 19 genetic codes currently regarded relevant by the NCBI (As compiled by Andrzej Elzanowski and Jim Ostell, updated April 30, 2013, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Utils/wprintgc.cgi), which could be an advantage, especially when working with ‘exotic’ samples.

2.2 Alphabet reduction

Research on the functional redundancy of amino acids dates back to the late 70s of the 20th century (Sander and Schul, 1979). It has mostly been used in structural research (Regan and DeGrado, 1988); however, the main purpose of reducing the alphabet today is the reduction of computational complexity while sacrificing as little sensitivity as possible.

Basically, all methods begin the reduction on the canonical 20-letter amino acid alphabet that includes all proteinogenic amino acids, without the rare amino acids Selenocystein (U) and Pyrrolysine (O) and that does not include a character for the STOP-codon and none of the wildcard characters frequently encountered (X for ‘any amino acid’; B for ‘N or D’; Z for ‘Q or E’). Depending on the method the target size may be fixed or variable, some research indicating that sizes as low 5 are sufficient (Bacardit et al., 2009), most suggesting that 10–12 letters are required and/or most effective (Li et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2000; Ye et al., 2011). Of the programs previously introduced, both RAPSearch2 and UBlast use the 10-character reduction developed by Murphy et al. (2000), subsequently referred to as Murphy10. Both programs apply the reduction only during seeding and do the extension on the regular alphabet to achieve a higher sensitivity in the final step. PAUDA uses a different kind of reduction, which it calls pseudo-DNA or pDNA, because it reduces to target size 4, the size of the DNA/RNA-alphabet. This enables PAUDA to use Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) in its pipeline (which was built to work in DNA-space). To compensate for the loss of specificity per character, the much longer seed length of 18 is chosen.

Owing to its popularity (Edgar, 2010; Zhao et al., 2012) and its success in empirical comparisons (Ye et al., 2011), we chose to implement the Murphy10 reduction (Murphy et al., 2000). It is based on amino acids’ correlation in the Blosum50 substitution matrix and the canonical 20-letter alphabet. In addition, we generated alphabet reductions from SeqAn’s 24-letter alphabet and Blosum62 to increase sensitivity. This was successful, but sensitivity gains where bought with efficiency losses, so these are not part of default Lambda parameter profiles, yet they remain selectable as parameters.

2.3 Seeding with double indexing

Seeding, the identification of candidate regions for hits, is a crucial task in sequence classification. A good seeding strategy can decrease the overall running time by magnitudes. Over the course of time, several approaches have been used: Blast uses a finite state machine from all ‘related’ query k-mers, Bowtie searches its seeds in an FM-Index, RAPSearch uses a suffix array to find seeds, RAPSearch2 and UBlast use hash-tables. In contrast, Lambda uses a double indexing search approach, which was originally developed for the Masai read mapper (Siragusa et al., 2013). Double indexing refers to the fact that, in contrast to all of the other tools discussed, Lambda builds an index over both the seeds (of the queries) and the subject sequences. The indexing structure built on the query sequences is a Radix trie and the indexing structure built over the subject sequences is a suffix array that is conceptionally used as a suffix trie (Other data structures, like FM-indices are also supported, but the Masai publication recommends the suffix array for speed reasons). The suffix array is then searched by backtracking (Ukkonen, 1993), but with the trie of the seeds instead of a single sequence. Through the backtracking, all subtrees in the suffix trie are explored until the distance to the query sequence becomes too large (Details of the post-processing of candidate regions can be found in the supplements). Using a Radix trie for the queries ensures that multiple seeds are processed in parallel.

2.4 Extension

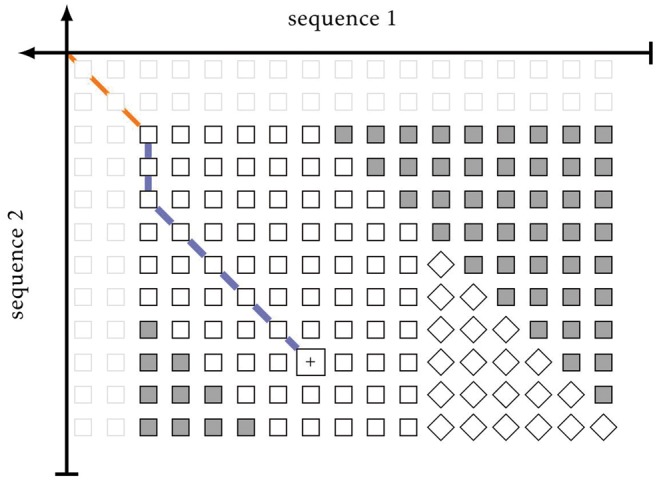

The last step in verifying a candidate region is the computationally expensive extension phase, which follows the post-processing of candidate regions (described in the supplements). This is usually done by means of dynamic programming. The algorithms are adapted from Needleman and Wunsch (1970), Smith and Waterman (1981), Gotoh (1981) and Hirschberg (1975). To avoid needlessly computing the full dynamic programming matrix, we added functionality similar to the original x-drop algorithm (Altschul et al., 1990). By specifying an x-drop parameter, columns of the alignment will only be computed for as long as the current column maximum does not fall x below the overall maximum seen so far. This algorithmic approach applies the x-drop paradigm only to the horizontal dimension; extension in vertical space is in turn limited by a fixed size band (Chao et al., 1992); see Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Banded right extension of alignment. The seed alignment is orange, the right extension purple; white solid cells are computed, grey cells are out of the band; tilted cells would have been computed, but were not, owing to the x-drop; cell with + contains the last and global maximum

The x-drop and the width of the band can be set by the user, and the latter can be set as an absolute value, be dynamically computed from the query sequence’s length, or be deactivated. Choosing non-linear growth of the band accounts for the fact that the expected length of local alignments (and thereby the chance for gaps) does not grow linearly with sequence length. In fact, it grows logarithmically (The raw score influences the e-value exponentially, while the length is a simple factor; because the expected raw score grows linearly with length of the match (Altschul and Gish, 1996), the lengths of the matches need to increase logarithmically with the length of one of the sequences to maintain the same e-value), which is why this was chosen as default band parameter. For the x-drop parameter a default of 30 was chosen, which is similar to UBlast (32) and BLAST (27) (in its initial gapped extension) (BLAST uses bit-score x-drops with 15 as default; a bit score of 15.0086 corresponds to a raw score of 27 in the default scoring scheme). The entire seeding and extension phase are run in parallel over contiguous blocks of queries. This is implemented with OpenMP (Dagum and Menon, 1998).

3 RESULTS

We performed a comprehensive experimental evaluation of Lambda and competing tools on two real-world datasets. All these tests were conducted on a Debian GNU/Linux 7.1 system (http://www.debian.org), with 2× Intel® Xeon® E5-2667V2 CPUs at 3.3 GHz (a total of 16 physical, 32 virtual cores) and 384 GB of RAM. All temporary data, intermediate data and both input and output files were read from and written to a tmpfs, i.e. a virtual filesystem in main memory. This prevents disk-caching effects from disturbing the benchmark, and increases overall performance. The latter effect is stronger on IO-heavy tools, but since memory is a small cost factor in bioinformatics pipelines, we recommend this approach for general use as well.

All programs were run with 16 threads and an e-value cutoff of 0.1 (more on scoring below). The running times do not include the creation of a database index. However, for Lambda they include the time needed for indexing the query sequences. Memory usage is measured as the maximum of the sum of the process and its child processes’ virtual memory resident set size in/proc. This did not work for PAUDA, which uses difficult-to-track java processes. Here we give 20 GB as an upper bound because this is the maximum reserved by the Java Virtual Machine; the publication states that memory usage is up to 16 GB.

3.1 On scoring

The quality of an alignment in BLAST and BLAST-like programs is indicated by either a bit score or an e-value, of which the latter takes sequence lengths into account and the former does not. Most metagenomic studies recommend an e-value cutoff of to (Lamendella et al., 2011; Mackelprang et al., 2011; Wommack et al., 2008), but some go as low as (Tetu et al., 2013) or (Eikmeyer et al., 2013). Unfortunately, although e-value calculation is widely adopted and accepted, different programs seem to be unable to consistently reproduce BLAST’s e-values [This is independent of conditional compositional score matrix adjustments (Altschul et al., 2005), which are deactivated, as no other programs support them]. Due to changes in the statistical model, even e-values calculated by different implementations and revisions of BLAST are not equal. This is not true for bit-scores, which are very close for identical alignments.

Because the only statistical difference between bit scores and e-values is the consideration of the total length of subject sequences—which is constant for each benchmark—and the length of the current query sequence—which only varies a little throughout each benchmark—we chose to use a minimum bit score instead of a maximum e-value as cutoff. The minimum bit score selected was the average bit score of all BLAST results that yielded an e-value between and . This is in line with the e-values used in the publications of competing tools. The bit-score cutoff was applied to the results a posteriori, after an initial parameter of was set as e-value cutoff for all programs in the benchmark. This ensures that no valid results are lost early on in the benchmark, and comparability is maintained, even if a longer-than-average query sequence (that would have a higher e-value) is encountered.

Concerning the choice of scoring matrix, we chose Blosum62, as this is the de facto standard and the only available choice for PAUDA and RAPSearch2. Lambda does, however, also support Blosum45 and Blosum80, as well as manual scoring parameter selection.

3.2 Measures of sensitivity

Different indicators can be used to define sensitivity, of which the total number of valid results is the most obvious one. It is relevant to research where all or up to n matches per query are desired. In sequence classification (and many other use-cases) we are only interested in the single best result for every query sequence (by definition we are looking for the closest matching sequence), so most approaches use the number of matched queries as the critical indicator (Huson and Xie, 2013; Ye et al., 2011).

As mentioned in the beginning, we will use the results of BLAST as the gold standard. Hence, we want to see if programs actually recall BLAST’s hits, i.e. whether the best match is on the same subject sequence, or whether they classify the query sequence as something possibly different by assigning it to a different subject. Arguably, a query assigned to a different subject sequence does not necessarily mean that the match is inferior. However, no heuristic tool to date has shown to be significantly more sensitive than BLAST, and none of the compared tools claims to be, so it is a fair assumption that a high BLAST recall is a predictive indicator of a high sensitivity. This is also theoretically founded by BLAST having a lower effective seed length, higher x-drop values and more steps of realignment.

The recalled matches are further categorized by the benchmark depending on their bit score. These categories demonstrate whether the alignments are of comparable quality, which would be an indicator for the ability to reproduce results at more stringent cutoffs, and a general clue on the capabilities of the algorithms. In Tables 2 and 3 there is one column for the number of all recalled matches and one column (labeled ‘≳’) for all recalled matches, which scored no worse than 90% of BLAST’s bit score.

Table 1.

Properties of the two datasets

| Dataset I | Dataset II | |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Bovine Gut | Sargasso Sea |

| Average read length | 72 bp | 818 bp |

| Number of reads | 58 240 283 | 1 982 807 |

| Number of reads selected | 1 200 000 | 100 000 |

| Selected read lengths | 72 bp | bp |

| Minimum bit score | 42.0695 | 48.5243 |

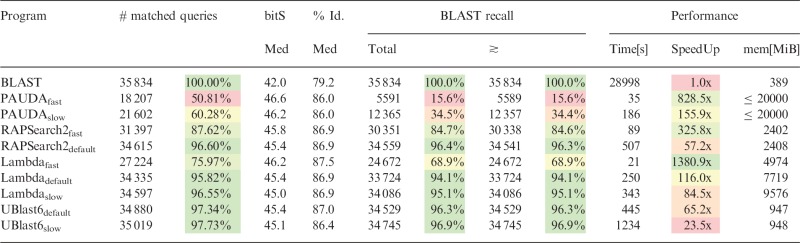

Table 2.

Results overview of dataset I (Illumina reads)

|

Note: Relative measures highlighted and in comparison with BLAST; green indicates the best results of a column, followed by yellow (satisfactory) and red (worst). The ‘≳’ column contains only recalls with bit scores ≳ to BLAST’s.

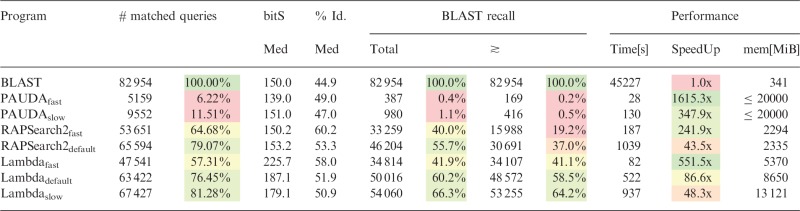

Table 3.

Results overview of dataset II (Sanger reads)

|

Note: Relative measures highlighted and in comparison with BLAST; green indicates the best results of a column, followed by yellow (satisfactory) and red (worst). The ‘≳’ column contains only recalls with bit scores ≳ to BLAST’s.

3.3 Applications

The applications compared are the following: BLAST by NCBI, version 2.2.27+ (Camacho et al., 2009).

Pauda in version 1.0.1 (Huson and Xie, 2013); both the slow mode and the fast mode are benchmarked (PAUDAslow and PAUDAfast, respectively); the Bowtie2 version used in conjunction with PAUDA is 2.1.0.

RAPSearch2 (Zhao et al., 2012) in version 2.12, which claims significant speed improvements to the previous version and which supports an extra-fast mode—both of which were benchmarked; the current version (2.14) crashed on one of our datasets and was not included; however, the homepage claims no performance improvements since 2.12.

UBlast by Edgar (2010): only 32 Bit binaries (and no source code) are freely available, which is why these were used; initially, version 7.0.1001 was tested, but this produced poor/no valid results on both datasets, so we chose to include version 6.0.307 instead. UBlast advertises an acceleration parameter as a convenient way to tune sensitivity, so we chose to benchmark both, the default (0.8 according to the manual) and with a value of 1, which should be slower but maximally sensitive.

Lambda is compared in three different configurations; the default and sensitive/slow profiles both use approximate seeding with seed length 10, one allowed mismatch and the Murphy10 alphabet, they differ only in that the default profile has non-overlapping seeds, while the slow profile generates seeds that overlap by five amino acids; the fast profile uses no alphabet reduction and has exact half-overlapping 8-mers as seeds.

Not all of the applications support masking low-complexity regions ‘online’, and because the query needs to be translated, it is difficult to mask it before giving it to the programs. Therefore, only the database was masked before doing the comparison and all other masking was deactivated. Where applications supported it, soft-masking was used (BLAST, Lambda, UBlast). The database for PAUDA was hard-masked, as it supports no form of soft-masking. In all cases the SEG algorithm (Wootton and Federhen, 1993) was used. RAPSearch2 could not be configured to not use its internal masking and it was not clear from the publication whether query, database or both are masked, and thus, the database was not ‘pre-masked’ for RAPSearch2.

3.4 Datasets

For Illumina reads, we used SRR020796 (Dataset I), a reference dataset of the highly optimized RAPSearch2. It is sampled from the bovine gut and an example of a metagenomic application in medicine.

The second dataset (Dataset II) was retrieved from the servers of the J. Craig Venter Institute (https://moore.jcvi.org/sargasso/), it is the dataset presented in one of the most highly cited, early metagenomic studies (Venter et al., 2004). The reads were sequenced with Sanger’s method. Because Sanger sequencing and 454 sequencing produce reads of similar accuracy and lengths (Liu et al., 2012), this dataset should have informative value for both technologies.

We chose these two datasets to have representatives of the different sequencing approaches, especially different read lengths, as some programs might be adapted better to one use case. The difference in datasets also helps to prevent over-optimization of heuristic parameters. The database of subject sequences used for all runs was UniProtKB Swiss-Prot (http://www.uniprot.org/).

3.5 Benchmark results

Dataset I

Table 2 contains a detailed overview of the results on dataset I. The general observation is that Lambda, UBlast6 and RAPSearch2 have a similar number of matched queries () compared with BLAST, with UBlast6 being slightly better than the rest. Different profiles (except the fast settings of Lambda and RAPSearch2) seem to have little influence on the amount of assigned queries, and the distributions of bit scores are similar, also compared with BLAST. PAUDA is far behind in all aspects; it produces only 50 and 60% of the amount of queries with matches and in total only recalls 16 and 35% of BLAST’s results.

The greatest speed-up compared with BLAST is ∼1380× achieved by Lambdafast, which is even faster than PAUDAfast by a factor of ∼1.6×. Next comes RAPSearch2fast with a speed-up of >325× compared with BLAST. In the default mode, Lambda is about twice as fast as RAPSearch2 while having a similar sensitivity. Hence, when speed is priority, Lambda is the clear winner. Even with respect to sensitivity, RAPSearch2 and UBlast are only marginally better.

Dataset II

The results on the second dataset with longer reads have more variance, but some trends are similar to dataset I. Table 3 shows that PAUDA is not well suited (and was not designed) for long reads, it produces <11% of BLAST’s amount of matched queries, even in slow mode, and it recalls <2/0.4% of BLAST’s assignments. UBlast6 fails to run on this dataset because it runs out of memory, likely due to limitations of the academic 32 bit version. Similar to dataset I, Lambda is about twice as fast as RAPSearch2 in its respective modes.

In its default mode, Lambda has slightly less matched queries (76.5 versus 79%) while having a higher BLAST recall (60.2 versus 55.7%, respectively 58.5 versus 37%). Lambda’s more sensitive slow mode beats RAPSearch2’s default mode, both in regard to sensitivity and speed. Thus, for this dataset, Lambda’s profiles are well suited for different research objectives or constraints.

Memory usage differs slightly for all the applications with Lambda using in the range of 5–13 GB, RAPSearch2 around 2.4 GB. UBlast6 needs only ∼1 GB of main memory for dataset I, but for dataset II, it obviously exceeded its 4 GB limitation. While Lambda’s memory usage is not extraordinarily high, it can be reduced further by a command-line parameter that offers a convenient memory to runtime trade-off. The impact of this parameter on memory usage is much stronger than on speed, so this is worthwhile in memory-constrained environments, e.g. increasing the so-called partition factor from 2 to 3 on dataset II, and Lambdaslow reduces memory usage by 3 GB (23%) while only increasing runtime by 30 s (3%).

4 DISCUSSION

For our test datasets, the fast PAUDA program seems to be an unsuitable choice, when recalling BLAST’s results is important. One possible explanation for the poor performance is that Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012)—which works at PAUDA’s core and is designed for read mapping—performs poor in its local alignment mode, when the expected local alignment size is much shorter than the original read. Another factor of why PAUDA likely misses many hits early on is that its seeds are long. Finally, the bad rate of BLAST recalls might be explained by PAUDA apparently not performing a realignment in regular protein space. A slightly lower recall could have been the outcome of hard-masking, but not to this extent (only 0.4% of BLAST’s best matches are recalled on the second dataset). PAUDA’s speed is comparatively high, but even if taking the measure of results per time into account (which is discussed in PAUDA’s publication), Lambda’s fast profile is always a better choice.

RAPSearch2 is a sensitive program with good results on both datasets. It outperforms Lambda slightly in sensitivity on dataset I, but is in turn outperformed on dataset II. It beats UBlast in speed, but is ∼2–4 times slower than Lambda in the respective modes.

Of UBlast we had to compare an older version because the newest (UBlast7) did not produce correct results. We evaluated the free 32 bit version, which allowed us to use it only on dataset I. It performed well there in terms of sensitivity; however, it came out as one of the slowest programs.

The evaluation of the specificity is a challenging task, as there is no ground truth, and hence, a definition of specificity is difficult. To gain more insight into the composition of the results of different tools (and their comparability), we included a cluster analysis conducted with MEGAN (Huson et al., 2007) in the supplements. It confirms the previous findings, i.e. similar results between RAPSearch2, UBlast and Lambda.

5 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

We can conclude that Lambda is of comparable overall sensitivity to state-of-the-art tools. With speed-ups of 86–116× in default mode and 551–1380× in fast mode (compared with BLAST), it is significantly faster than the other tools in their respective modes. The amount of required memory is higher then that of RAPSearch, but still moderate for modern computers and can easily be adjusted for constrained situations.

In contrast to some of the other programs, Lambda is free and open-source software, has all of its parameters documented and requires no external libraries beyond SeqAn. Lambda produces BLAST-compatible output and can easily replace it in analysis pipelines.

Altogether, Lambda is a worthwhile alternative to the established tools—especially (but not only) when speed is a concern.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank René Rahn for his work on the SeqAn alignment module, Enrico Siragusa for discussions about double indexing and the whole SeqAn team for their work on the library.

Funding: JS was supported by the BMBF [16V0080].

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Bio. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W. Local alignment statistics. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:460–480. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, et al. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 2005;272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacardit J, et al. Automated alphabet reduction for protein datasets. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet AL, Cummings MP. A comparative evaluation of sequence classification programs. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao KM, et al. Aligning two sequences within a specified diagonal band. CABIOS. 1992;8:481–487. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagum L, Menon R. OpenMP: An Industry-Standard API for Shared-Memory Programming. IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. 1998;5:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Döring A, et al. SeqAn An efficient, generic C++ library for sequence analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikmeyer FG, et al. Detailed analysis of metagenome datasets obtained from biogas-producing microbial communities residing in biogas reactors does not indicate the presence of putative pathogenic microorganisms. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2013;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde AK, et al. MicroRazerS: rapid alignment of small RNA reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:123–124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach W, Stoye J. Taxonomic classification of metagenomic shotgun sequences with CARMA3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. An Improved Algorithm for Matching Biological Sequences. J. Mol. Bio. 1981;162:705–708. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg DS. A linear space algorithm for computing maximal common subsequences. Commun. ACM. 1975;18:341–343. [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Xie C. A poor man’s blastx—high-throughput metagenomic protein database search using pauda. Bioinformatics. 2013;30:38–39. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, et al. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 2007;17:377–386. doi: 10.1101/gr.5969107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr B, et al. STELLAR: fast and exact local alignments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl. 9):S15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S9-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen P, Holm L. SANS: high-throughput retrieval of protein sequences allowing 50% mismatches. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:438–443. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause L, et al. Phylogenetic classification of short environmental DNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2230–2239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamendella R, et al. Comparative fecal metagenomics unveils unique functional capacity of the swine gut. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, et al. Reduction of protein sequence complexity by residue grouping. Protein Eng. 2003;16:323–330. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, et al. Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/251364. 2012, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackelprang R, et al. Metagenomic analysis of a permafrost microbial community reveals a rapid response to thaw. Nature. 2011;480:368–371. doi: 10.1038/nature10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LR, et al. Simplified amino acid alphabets for protein fold recognition and implications for folding. Protein Eng. 2000;13:149–152. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman SB, Wunsch CD. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Bio. 1970;48:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan L, DeGrado WF. Characterization of a helical protein designed from first principles. Science. 1988;241:976–978. doi: 10.1126/science.3043666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander C, Schul G. Degeneracy of the information contained in amino acid sequences: evidence from overlaid genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1979;13:245–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01739483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragusa E, et al. Fast and accurate read mapping with approximate seeds and multiple backtracking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Waterman M. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetu SG, et al. Life in the dark: metagenomic evidence that a microbial slime community is driven by inorganic nitrogen metabolism. ISME J. 2013;7:1227–1236. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukkonen E. Approximate string-matching over suffix trees. In: Apostolico A, et al., editors. Combinatorial Pattern Matching, Vol. 684 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer; 1993. pp. 228–242. [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the sargasso sea. Science. 2004;304:66–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese D, et al. RazerS–fast read mapping with sensitivity control. Genome Res. 2009;19:1646–1654. doi: 10.1101/gr.088823.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese D, et al. RazerS 3: Faster, fully sensitive read mapping. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2592–2599. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wommack KE, et al. Metagenomics: read length matters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:1453–1463. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02181-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JC, Federhen S. Statistics of Local Complexity in Amino Acid Sequences and Sequence Databases. Comput. Chem. 1993;17:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, et al. RAPSearch: a fast protein similarity search tool for short reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, et al. RAPSearch2: a fast and memory-efficient protein similarity search tool for next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:125–126. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.