Abstract

Motivation: As a natural consequence of being a computer-based discipline, bioinformatics has a strong focus on database and software development, but the volume and variety of resources are growing at unprecedented rates. An audit of database and software usage patterns could help provide an overview of developments in bioinformatics and community common practice, and comparing the links between resources through time could demonstrate both the persistence of existing software and the emergence of new tools.

Results: We study the connections between bioinformatics resources and construct networks of database and software usage patterns, based on resource co-occurrence, that correspond to snapshots of common practice in the bioinformatics community. We apply our approach to pairings of phylogenetics software reported in the literature and argue that these could provide a stepping stone into the identification of scientific best practice.

Availability and implementation: The extracted resource data, the scripts used for network generation and the resulting networks are available at http://bionerds.sourceforge.net/networks/

Contact: robert.stevens@manchester.ac.uk

1 INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is defined by its use of available methods. We continually refine existing methods and develop new ones, and this cycle of innovation, implementation and confirmation is at the heart of scientific progress. The merits of a piece of research, i.e. its contribution and impact, are a direct consequence of the methods used (Eales et al., 2008). In this article, we focus on the discipline of bioinformatics and the use of computers in the analysis of biological data. Knowledge of the relationships between the most widely used resources within bioinformatics (‘common practice’) permits a representation of the contribution of software and databases to biological research, potentially enabling researchers to identify and select the most appropriate approaches for their data analysis.

Resource selection is a particular problem within bioinformatics, where the ‘resourceome’ (Cannata et al., 2005) has been growing at an unprecedented rate since nucleic acid sequencing became widespread in the 1980s, leading to the emergence of key tools such as BLAST, which is still widely used (Altschul et al., 1990). Managing this overwhelming resource portfolio requires identifying which ones are commonly used, how they are used and for what they are used. While there are repositories of bioinformatics resources (e.g. The Bioinformatics Links Directory; Brazas et al., 2011) and services (e.g. BioCatalogue; Bhagat et al., 2010), the biomedical literature is still the most suitable place to look for patterns of database and software usage to provide an overview of developments in the community, and thus help identify common practice (Stevens et al., 2003).

In this article, we use several well-established techniques in text mining to extract, filter, combine and analyse frequently reoccurring resource name pairs in articles’ methods sections. We use these pairs to build resource networks, thus providing a snapshot of database and software common usage patterns within the bioinformatics literature. A few previous studies exist in this area, but they focus on a specific subdomain or task, e.g. phylogenetics (Eales et al., 2008) or natural language processing (Kovačević et al., 2012), and not resource usage across bioinformatics. We build our work on a previously developed named entity recognizer for databases and software within bioinformatics (Duck et al., 2013), which we use to automatically extract resource names mentioned across a large corpus of full-text documents.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our approach has five main steps: (i) full-text corpus generation, (ii) extraction of resource name mentions, (iii) identification of method sections, (iv) frequent resource pair mining and (v) network generation.

(i) Corpus generation. We filtered the open-access subset of PubMed Central (PMC; downloaded February 2013) (Roberts, 2001) to only full-text articles that had ‘Bioinformatics’ as a MeSH term associated with their journal, resulting in 22 376 articles from 67 journals; this corpus contained no articles published before 2000. We note that just three journals (BMC Bioinformatics, BMC Genomics and PLoS Computational Biology) contribute over 50% of the total documents to this corpus.

(ii) Resource extraction and categorization. We first ran bioNerDS (Duck et al., 2013) on the corpus to extract database and software names at the mention level. Note that bioNerDS reported F-scores of 63–91% at the mention level. There were 702 937 total mentions and 167 697 mentions at the document level (ignoring multiple mentions of the same resource within a single document) of 31 053 unique names; 93% of the documents contained at least one resource mention. We then filtered the resource mention data by only considering resource names mentioned in at least two different documents, leaving 520 590 resource mentions (6302 unique), and thus removing 24.6% of the total mentions. This not only removed resources just mentioned in a single document—which would not be indicative of common practice—but it also helped filter out several false-positive mentions, as resources appearing in few documents showed a higher false-positive rate. We also excluded the generic resources Bioconductor and R, as they can be used in a wide array of differing situations, but we kept specific Bioconductor package mentions (e.g. affy), which do indicate specific tasks. We have additionally filtered some common false-positive terms (e.g. PSSM, EST, etc.). This left 443 193 resource mentions (6262 unique).

Each unique resource name is categorized as either a database (including datasets, ontologies, etc.) or software (including web services, packages, etc.) at the corpus level (for a full definition, see Duck et al., 2012). Categorization is done automatically and is based on several pieces of information. Firstly, the bioNerDS dictionary entries have already been categorized as either databases or software wherever possible, and secondly, we score names by counting the indicative keywords found around all the name mentions within text during extraction, finally taking the majority decision (e.g. more database indicative terms than software ones). In the cases when there is insufficient evidence to assign a specific category, we assigned the ‘unknown’ class to that name. Overall, we identified 201 113 mentions of software, and 233 920 mentions of databases in the corpus, and thus removing 8160 ‘unknown’ mentions (leaving 3872 unique software names and 2143 unique database names).

(iii) Methods section filtering. To identify only resource mentions that were used as part of the method presented in an article, we focus on identification of method sections. Previous work in this area has focused on sentence-level classification (‘zoning’), often using a machine learning approach (Kovačević et al., 2012). We instead make use of regular expressions to identify an entire section, rather than individual sentences, assuming that relevant sentences are placed within the correct section (in particular for method sections). We use section headings to classify the text into one of two possible sections: method or non-method.

To engineer regular expressions for section identification, we first extracted section heading titles from a random sample of 100 full-text PMC articles (using the associated XML tags for section headings). These were grouped and associated manually to form the heading texts with which to search. Additional variants were generated using simple transformations (e.g. case, plural, numbered sections, etc.). Once a method heading is detected at the start of a sentence or paragraph, the associated section classification continues until an alternative (non-method) section heading is detected. To further evaluate the approach, we selected another set of 100 full-text PMC articles and manually verified the recognized method sections. The proposed approach showed a precision of 97.2% with a recall of 79.2%. All resource mentions that were outside the recognized method sections where then discarded, leaving 65 451 software mentions (3289 unique), and 69 466 database mentions (1711 unique).

(iv) Frequent resource pair mining. We next extract common pairs of resources co-occurring within the same method section, hypothesizing that—with enough data—they may reveal the main individual experimental steps in bioinformatics. In particular, for each resource, we pair it with the resource that immediately follows it in text (based on mention offsets, ignoring non-resource mentions), aiming also to infer the directionality within each pair. We assume that given sufficient source material, the more common ordering in-text will be the ‘correct’ (applicable) one.

We consider two cases: co-occurrence of software mentions, and co-occurrence of database and software mentions (any combination thereof). Our dataset generated 22 880 total resource pairs (13 965 unique) for our software-only set, and 54 562 pairs (29 066 unique) for our databases and software names set. In the interest of exploring common practice, we removed pairs that were only extracted from a single document. This removed 12 101 pairs from our software set and 25 111 pairs from our databases and software set.

(v) Statistical filtering and network generation. With the two possible orders of a given pair, and the occurrence count of each, we use a binomial test to assign a confidence to each pair order, thus providing the probability of a particular order occurring a given number of times by chance. From this, we filter the ordered resource pairs down to only those that are above a certain confidence threshold using cut-offs at 95 and 99%. Using a confidence threshold of 95% provides 2518 software pairs (145 unique) and 7001 software and database pairs (297 unique), whereas using a threshold of 99% results in 1450 software pairs (55 unique) and 3383 database and software pairs (95 unique). Using these final resource pairs, we generate a network using Cytoscape (Smoot et al., 2011), where nodes are the resources appearing in those pairs, and a directed edge between two nodes reflects the extracted ordering of the given resource pair.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We present the resulting networks with software-only and software and/or database pairs built using the 95 and 99% confidence levels, respectively, which have been extracted from 22 376 full-text articles.

To evaluate the accuracy of the automatic categorization of resources as databases and software, we manually classified three separate lists of 50 resource names:

The first group had 50 names randomly selected from the set of all unique names.

The second set was selected in proportion to resource mention level counts, enabling repeats of frequent names.

The last group of 50 names were selected from the final set of all names, which occur within the networks presented in this article.

Table 1 has the resulting accuracies for each of these groups. Note that the accuracy increases as we test a more specific subset of resource name classifications, showing that the filtering steps we used during network generation removed the majority of the incorrectly categorized instances.

Table 1.

Resource classifier evaluation scores

| Total | Correct (%) | Incorrect | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 50 | 28 (56) | 5 | 17 |

| Group 2 | 50 | 33 (66) | 3 | 14 |

| Group 3 | 50 | 43 (86) | 3 | 4 |

Note: The accuracy of the classifier increases as we test more specific subsets of resource names (more filtered groups). An instance is marked as unknown if the class was inconclusively categorized during manual evaluation, often because of insufficient evidence—this does not necessarily imply that the automatically assigned class is incorrect (e.g. it is correct in cases where the resource mention is not a false-positive hit).

3.1 Most common resource pairs

Table 2 shows the most common software pairs extracted with a minimum of a 99% confidence level. The pairs focus primarily on sequence search and alignment (generally in that order)—a task central to various bioinformatics analyses. In addition, there are a couple of sequence assembly pairs (containing Phred, Phrap, Consed), which are all part of the same package.

Table 2.

Most common 99% ordered software pairs

| Software-directed pair | Total count | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| BLAST → ClustalW | 205 | 14.1 |

| BLAST → PSI-BLAST | 103 | 7.1 |

| Phred → Phrap | 89 | 6.1 |

| ClustalW → MEGA | 77 | 5.3 |

| Cluster → Tree View | 75 | 5.2 |

| Phrap → Consed | 51 | 3.5 |

| ClustalW → PHYLIP | 41 | 2.8 |

| BLAST → ClustalX | 43 | 3.0 |

| BLAST → MUSCLE | 40 | 2.8 |

| BLASTN → ClustalW | 39 | 2.7 |

Note: The contribution is calculated as the total count (after applying all our data filters), divided by the 1450 total pairs extracted.

To assess the quality of extracted pairs, we separately evaluated all the extracted resource pairs remaining at both the 95 and 99% confidence boundaries. This was done by taking a given ordered pair, linking it back to the full-text articles whence it was extracted, and manually assessing whether the pair order agreed with the usage of the resources in the associated articles. Each ordered pair received one of the following classifications:

Correct: Extracted order agreed with the order of resource use in text.

Partial: Extracted order either mostly agrees, or agrees but there is an important resource step missing. This can also be the case where there is an indirect link between the resources.

Incorrect: The order extracted contrasts with the order of usage in the text, or where there is no clear (even indirect) link between the resources.

Same: The two resources are generally used to do equivalent tasks (e.g. ClustalW and MUSCLE are both sequence alignment tools).

Our automated pair extraction approach appears to provide a good indicator of resource pairing (Table 3). A higher confidence level resulted in a higher proportion of ‘correct’ name pairs, and a lower proportion of pairs categorized as ‘same’. We note that there is an increase in the proportion of ‘incorrect’ pairs for our software-only set despite a higher confidence boundary (perhaps because of the small sample size), but the absolute number of errors decreased by 50%.

Table 3.

Manual evaluation scores for the resource name pairs we extracted at various confidence levels

| Software-only |

Software/databases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% | 99% | 95% | 99% | |

| Total pairs | 141 | 53 | 288 | 90 |

| Correct (%) | 66.7 | 77.4 | 45.1 | 54.4 |

| Partial (%) | 13.5 | 7.5 | 14.9 | 12.2 |

| Incorrect (%) | 5.7 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 10.0 |

| Same (%) | 14.2 | 7.5 | 27.4 | 23.3 |

Note: We ignore pairs resulting from a bioNerDS false-positive match during manual evaluation—this excluded four and two pairs from the 95 and 99% software-only evaluation, and nine and five pairs from the 95 and 99% databases and software pairs evaluation.

3.2 Resource networks

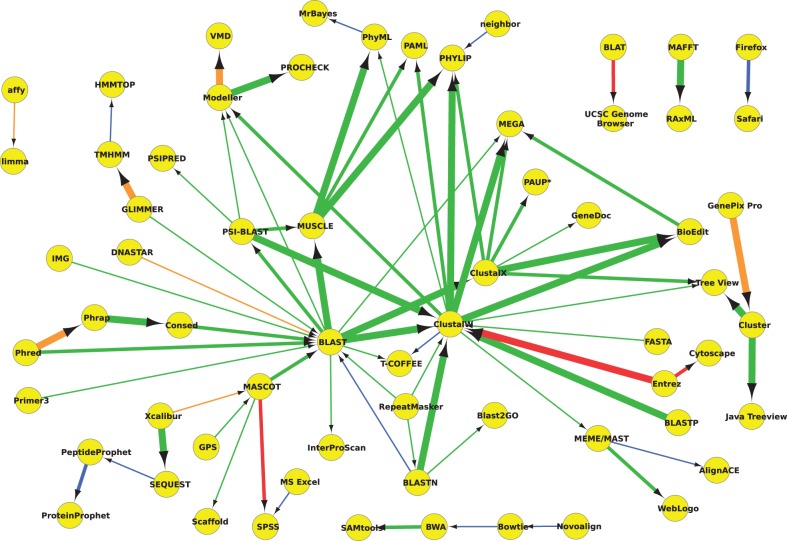

Figure 1 provides a usage network generated by analysing software name mentions within the methods section with a 95% confidence threshold (the edges are weighted according to their confidence). There is a large central cluster of sequence alignment tools within this network, which could correlate to the broad applicability of these resources. This centre is split into homologue detection—search (BLAST, PSI-BLAST)—and then followed by (pair-wise) alignment (ClustalW, ClustalX, MUSCLE). Leading into this central series of connected components are several more domain-specific resources—a series of sequence assembly tools (e.g. Phred, Phrap, Consed), a gene locator (GLIMMER) and mass-spectroscopy software (MASCOT). There are two major routes out of the sequence alignment cluster, with links to the fields of proteomics (Modeller, PROCHECK, etc.) and phylogenetics (PhyML, PHYLIP, PAML, etc.). There is also a third route towards manual alignment editors (Tree View and BioEdit). This provides an overview of common stages within a bioinformatics pipeline: sequence assembly, homologue search, pair-wise alignment, protein modelling and protein visualization/evaluation. Importantly, this core route consists of edges with confidence above 99%. There is also a link between (Mozilla) Firefox and (Apple) Safari, which remains pervasive throughout many of the networks we present here. This link seems to originate from frequent comments on supported browsers (e.g. ‘Our web application can be accessed through all major web browsers, including Firefox, Safari …’).

Fig. 1.

Usage network for software name resource pairs, mentioned within the methods section only. The thickest edges surpass the 99.9% confidence level, medium 99% and the thinnest edges have a minimum confidence of 95%. Edges are colour coded according to their evaluated accuracy. Green edges are correct, orange are partial, red are incorrect; blue edges link resources that are categorized as same. For presentation purposes, we only include pairs (edges) that had at least 10 mentions

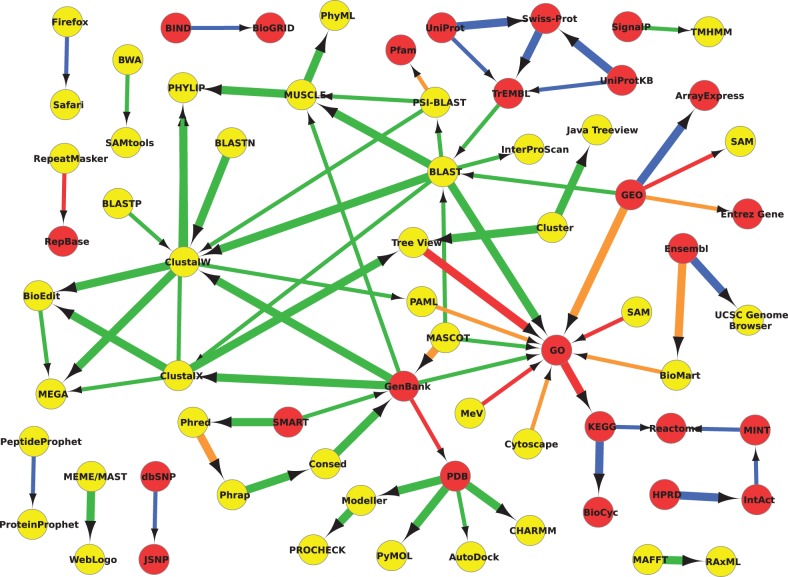

Figure 2 was generated by using both database and software names to form pairs. This addition of databases helps highlight where some of the data entry/annotation points are within the usage graph, assuming that databases are generally used for annotation, search and retrieval or deposition. This trend can be seen within the network. For example, UniProt (Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) all directly link into BLAST; GenBank links into several multiple sequence alignment tools, while the Protein Data Bank (PDB) links into various protein prediction and evaluation programs. In addition, the Gene Ontology (GO) is a data ‘sink’, as it covers a wide variety of annotation tasks, and there is a linked group of pathway databases (e.g. KEGG, BioCyc, Reactome).

Fig. 2.

Usage network for all resource pairs (databases – red, software – yellow), mentioned within the methods section. All edges have a minimum confidence of 99%. The edges are colour coded: green – correct, orange – partial, red – incorrect and blue – same. Note that there is a same link between Ensembl and the UCSC Genome Browser, as they are both genome databases—this is despite the fact that the Genome Browser is labelled as software, which is an automated classification error. For presentation purposes, we only include pairs (edges) that had at least 10 mentions

Interestingly, the extracted order of mentions of databases appears to be less reliable than that of software. A likely reason is that—in a written article—an author is more likely to use a tool on a database, rather than specifically getting data from a database before using these with a tool. Additionally, some database pairs were incorrect because of the structure of a paper—in particular, a paper may describe the in silico methods used, before listing all data resource locations at the end of the methods section (rather than at their point of use). Figure 2 helps highlight this as all the edges annotated as incorrect (in red) involve databases, and there are few correct (green) direct database to database links.

If we perform an additional statistical analysis of our results, using the method of directionality previously published by Hidalgo et al. (2009), we can draw similar conclusions from our networks. We see that annotation and statistical resources such as GO, SPSS, Cytoscape and WebLogo are significant network sinks, whereas common databases like TrEMBL, GEO and PDB are significant network sources. In general, databases are network sources, and software is a data sink. This conforms to the common assumption that bioinformatics access data within databases to perform various in silico analyses with software resources.

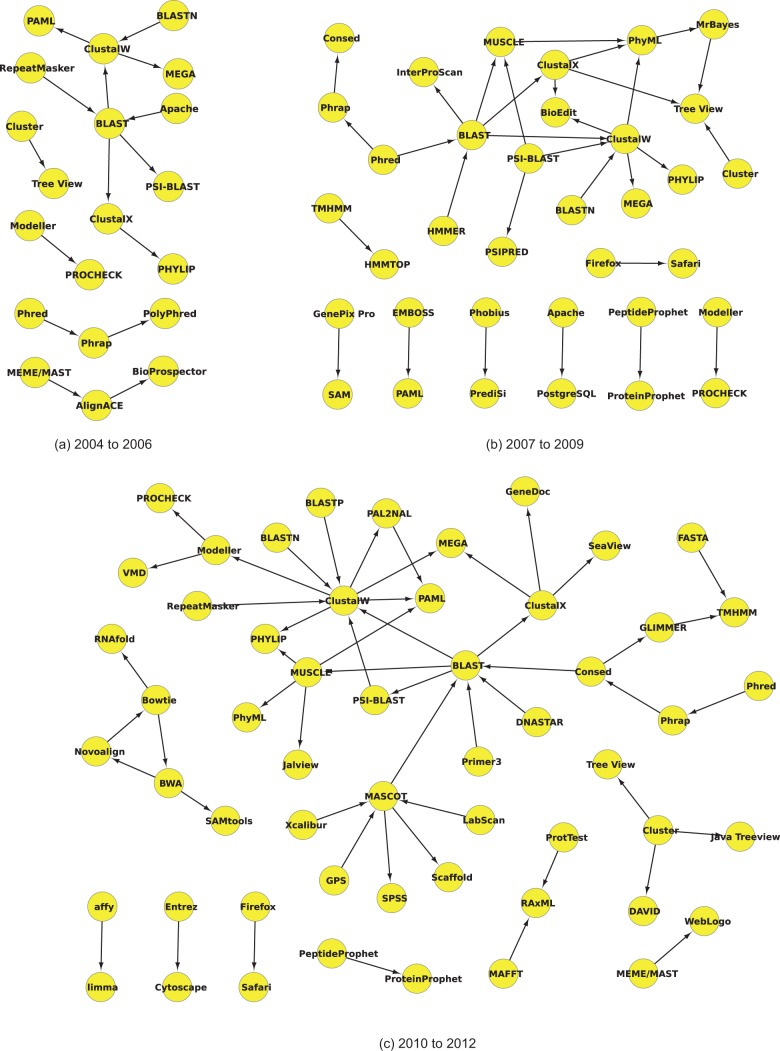

We further evaluated how the resource usage has changed over time. To do this, we split our dataset into three separate sets: 2004–2006, 2007–2009 and 2010–2012 (inclusive). These were chosen as a trade-off between the number of ranges (at least three) and ensuring there was enough data contained within each range to generate a meaningful network (note that there is insufficient data between 2000 and 2003, and incomplete data for 2013). We then ran our automatic resource pair extractor as before using a confidence threshold cut-off of 95%.

From 2004 to 2006 (Fig. 3a), there is a clear usage bias towards sequence alignment software (BLAST, ClustalW, ClustalX). Separately there is a triple of sequence assembly-based software (Phred, Phrap, PolyPhred), and a pair of clustering software and visualization tools (Cluster, Tree View). There is also a hint of phylogenetics with alignment links to PAML and PHYLIP.

Fig. 3.

Usage networks for software names within the given time frames (inclusive). All resource name pairs pass the 95% confidence level. (a) 2004 to 2006, (b) 2007 to 2009 and (c) 2010 to 2012

The 2007–2009 period features an expansion of resource pairs, in particular, those using sequence alignment software (e.g. the addition of MUSCLE and PSI-BLAST; Fig. 3b). In addition, these now directly link back to the assembly programs, although the ordering is not well established. Protein modelling also now features with a pair from Modeller (which predicts protein structures) to PROCHECK (which evaluates potential protein structures), as well as a link between TMHMM and HMMTOP (which are both protein structure predictors). There appears to be a general theme of visualization with mentions of BioEdit and Tree View, which are now tied to the main network. The phylogenetics field has also grown slightly, with PhyML and MrBayes, although PAML is no longer directly linked to the main network.

Finally, from 2010 to 2012 (Fig. 3c), the size of the network expands once again (in part because of the fact that there is the most literature published during this time frame). Phylogenetics has more links than before to sequence alignment (PhyML, PAML, PHYLIP) and has expanded with MAFFT and RAxML in a disjoint pairing. The protein-based chains have been expanded with protein visualization software (VMD), now both directly linking into sequence alignment. In addition, the more recent Novoalign, Bowtie, BWA and SAMtools make a preliminary link to the next-generation sequencing data now being produced and analysed. The Phred, Phrap, Consed ordering now looks more correct and directly links into BLAST for initial sequence analysis. Finally, we see the reappearance of the mass-spectroscopy link contained within our main network earlier (MASCOT; Fig. 1).

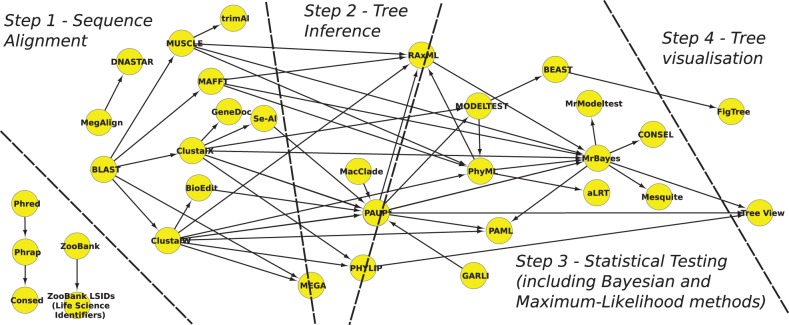

3.3 Phylogenetics comparison

To demonstrate how the usage patterns extracted can be used to suggest common practice within a subdomain, we explored the phylogenetics literature. Eales et al. (2008) have semi-automatically explored that literature previously and assigned methodological terms to one of four possible steps, which represent a common methodological process in phylogenetics: (i) sequence alignment, (ii) tree inference, (iii) statistical testing and data re-sampling and (iv) tree visualization and annotation. We checked whether our automatically extracted network of phylogenetics ‘methods’ reflects these four steps. For this, we restricted our dataset to only those PMC articles that matched the same regular expression used by Eales et al. (2008). We did not restrict the articles on publication year, but rather on journal MeSH term (all other filters remained).

Figure 4 shows the resulting network using a 95% confidence cut-off, indicating the four methodological steps common for phylogenetics. Because of some ambiguous resources that can do multiple tasks, several tools sit on the boundary between Steps ii and iii (and one between Steps i and ii). Otherwise, there is a clear split between the different stages, with only two ‘back’ arrows between PhyML and RAxML, and between GARLI and PAUP* (all involving ambiguous boundary resources). These results indicate that our approach is not only a viable way to extract common in silico usage patterns from the bioinformatics literature but that it could be also used to ‘infer’ common practice.

Fig. 4.

Usage network for software names within phylogenetics papers. The network is annotated into four steps, which correlate to those identified previously by Eales et al. (2008). Note that several ambiguous resources can be used to perform multiple steps

4 CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that it is feasible to automatically extract resource usage patterns from a large corpus of bioinformatics articles. The networks formed from these patterns show a general overview of core bioinformatics tasks and steps. Although our technique used for network extraction focuses on only the most used resources, it successfully captures what may be termed ‘bioinformatics 101’—that is, the core bioinformatics tasks of selection and alignment of sequences, along with a common pattern of biological analysis: that DNA sequences lead to proteins, which then form more complex 3D structures. Our results are an important first step in validating the long-held assumption that this forms the basis of all bioinformatics research and usage. Our networks also highlight some of the ways that bioinformatics has changed over time, with the recent emergence of the fields of next-generation sequencing and proteomics. Sequence alignment has maintained an important central role within the field and is often used as a link between other analyses and/or domains.

The results help provide an overview of the resource patterns used within bioinformatics, which can be considered an approximation of domain method. Comparing our usage patterns for phylogenetics with the model previously published by Eales et al. (2008) shows that our method extraction enables exploration of common practice within particular fields. For example, if a researcher has some particular data, tool or task in mind, our results could be used to generate suggestions on what has and can been done with the data, or what programs could be used for further research. Specifically, given any name pair, we can link back to where in the literature this pair was mentioned, offering the opportunity to discover what types of research could be performed with those resources.

Future work could involve refining the pattern extraction process, perhaps to enable sentence-level pairing using more sophisticated association techniques (e.g. dependency parsing or syntactic structure). Though our method can provide a generalized overview of the resources used (and their order of use), such a refinement could enable more fine-grained workflow extraction—an important step towards method validation and reproduction, as well as having implications for the spreading of knowledge and the monitoring of trends within methods. This could have implications in establishing or suggesting scientific ‘best practice’, using a variety of criteria, for example time (the more recent tools/databases, the better), author (focusing on ‘domain experts’), journal (preference for higher impact or specialist journals) or popularity (common practice). As such, if we restrict our network links to just those that adhere to a given ‘best’ criteria, this will limit the suggestions we would provide to just those within a network of best practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance given by IT Services and the use of the Computational Shared Facility at The University of Manchester for our full-text literature analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by a studentship to G.D. from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) to G.N., D.L.R. and R.S.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat J, et al. BioCatalogue: a universal catalogue of web services for the life sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W689–W694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazas MD, et al. The 2011 bioinformatics links directory update: more resources, tools and databases and features to empower the bioinformatics community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Suppl. 2):W3–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannata N, et al. Time to organize the bioinformatics resourceome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2005;1:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck G, et al. Ambiguity and variability of database and software names in bioinformatics. In: Ananiadou S, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Semantic Mining in Biomedicine (SMBM) 2012. pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Duck G, et al. bioNerDS: exploring bioinformatics’ database and software use through literature mining. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eales JM, et al. Methodology capture: discriminating between the “best” and the rest of community practice. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo CA, et al. A dynamic network approach for the study of human phenotypes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević A, et al. Mining methodologies from NLP publications: a case study in automatic terminology recognition. Comput. Speech Lang. 2012;26:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ. PubMed Central: the GenBank of the published literature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:381–382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoot ME, et al. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens R, et al. Proceedings of the UK e-Science Programme All Hands Meeting. 2003. Performing in silico experiments on the grid: a users perspective; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]