Abstract

Motivation: Accurate haplotyping—determining from which parent particular portions of the genome are inherited—is still mostly an unresolved problem in genomics. This problem has only recently started to become tractable, thanks to the development of new long read sequencing technologies. Here, we introduce ProbHap, a haplotyping algorithm targeted at such technologies. The main algorithmic idea of ProbHap is a new dynamic programming algorithm that exactly optimizes a likelihood function specified by a probabilistic graphical model and which generalizes a popular objective called the minimum error correction. In addition to being accurate, ProbHap also provides confidence scores at phased positions.

Results: On a standard benchmark dataset, ProbHap makes 11% fewer errors than current state-of-the-art methods. This accuracy can be further increased by excluding low-confidence positions, at the cost of a small drop in haplotype completeness.

Availability: Our source code is freely available at: https://github.com/kuleshov/ProbHap.

Contact: kuleshov@stanford.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Although modern sequencing technology has led to rapid advances in genomics over the past decade, it has largely been unable to resolve an important aspect of human genetics: genomic phase. Each human chromosome comes in two copies: one inherited from the mother, and one inherited from the father. Despite the fact that differences between these copies play an important biological role, until recently, decoding these differences (a process known as haplotyping or genome phasing) has been a major technological challenge.

In recent years, however, we have seen an emergence of new long read technologies (Kaper et al., 2013; Kitzman et al., 2010; Peter et al., 2012; Voskoboynik et al., 2013) that may one day enable routine cost-effective haplotyping. Because a long read comes from a single chromosome copy, it reveals the phase of all heterozygous genomic positions that it covers. By connecting long reads at their overlapping heterozygous positions, it is possible to extend this phase information into haplotype blocks, in a process referred to as single-individual haplotyping (SIH) (Browning and Browning, 2011).

Although from the molecular biology side, routine haplotyping seems close to becoming a reality, dealing with long read data remains non-trivial computationally. Under most formulations of the problem, it is NP-hard to recover the optimal haplotypes from noisy sequencing reads (Gusfield, 2001). This has led to a vast literature on heuristics for dealing with this problem as accurately as possible.

Here, we propose a new algorithm, ProbHap, which offers an 11% improvement in accuracy over the current leading method, RefHap. Unlike most other algorithms, ProbHap also provides confidence scores in addition to genomic phase. These scores can be used to prune low-accuracy positions and further improve haplotype quality, at the cost of phasing fewer variants.

The main algorithmic ideas of ProbHap are a new dynamic programming algorithm and a probabilistic graphical model. The dynamic programming algorithm determines the haplotypes that maximize the likelihood function specified by the probabilistic model as well as the probability that these haplotypes are correct. It can be seen as a special case of the well-known variable elimination algorithm (Koller and Friedman, 2009).

From a theoretical point of view, the likelihood function specified by our probabilistic model generalizes a well-known objective called the minimum error correction (MEC). Previously proposed exact dynamic programming algorithms for the MEC can be easily derived as special cases of the general variable elimination algorithm within our model. More interestingly, alternative formulations of this algorithm (corresponding to different variable orderings) result in novel exact algorithms that are significantly faster than previous ones. Thus, our work generalizes several previous approaches and provides a systematic way of deriving new haplotyping algorithms.

2 RELATED WORK

Most phasing algorithms solve a formally defined computational problem called sih, in which the goal is to minimize an objective called the MEC (see Section 5). This objective is NP-hard (Gusfield, 2001); therefore, most early work on the sih problem involved simple greedy methods (Geraci, 2010). More recently, these methods have been superseded by more sophisticated heuristics such as RefHap (Duitama et al., 2012) or HapCut (Bansal and Bafna, 2008) that involve solving a Max-Cut problem as a subroutine. There is also an exact dynamic programming solution to the sih problem; its running time is exponential in the length of the longest read (He et al., 2010).

Several probabilistic approaches have also been previously proposed, including HASH (Bansal et al., 2008), MixSIH (Matsumoto and Kiryu, 2013) and an algorithm used for reconstructing the diploid genome of Ciona intestinalis (Kim et al., 2007). These methods optimize an objective function similar to that of ProbHap using heuristics based on Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). They differ in the way in which they implement MCMC. In addition, MixSIH (Matsumoto and Kiryu, 2013) is to our knowledge the only package that also provides confidence scores at phased positions.

Probabilistic graphical models are widely used in the statistical phasing literature to determine haplotypes from a panel of individuals using linkage disequilibrium patterns. However, the vast majority of statistical methods do not use the partial phase information provided by long reads, and are not applicable to our setting. A notable exception is a recent method called Hap-Seq (He et al., 2012); without its statistical component it reduces to the well-known exact exponential-time algorithm mentioned above (He et al., 2010).

Also, there exists an extensive literature on the SIH problem from the perspective of combinatorial optimization (Lippert et al., 2002). Research in this field is aimed at optimizing combinatorial objectives such as minimum fragment removal, minimum SNP removal or MEC. This research is of a more theoretical nature and aims at providing a rigorous theoretical understanding of the SIH problem (Lippert et al., 2002).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Overview of ProbHap

ProbHap is based on a new exact dynamic programming solution for the SIH problem, which makes it more accurate than many existing methods. Its main drawback is a higher computational cost: its worst-case running time increases exponentially with the read coverage. Fortunately, modern long read technologies cover the genome at a relatively low depth (Duitama et al., 2012; Kitzman et al., 2010), making it possible to apply our algorithm to such data. In cases when the coverage is extremely high, ProbHap also uses a preprocessing heuristic to merge similar reads (see Section 4). In our experience, ProbHap handles long read coverages of up to 20×; however, it is not appropriate for higher coverage short read datasets.

The output of ProbHap is a set of haplotype blocks in the format of RefHap and HapCut. In addition, ProbHap also produces at each position three confidence scores that can be used to identify locations where the phasing results are less accurate. The posterior score represents the probability of correctly determining the phase of a SNP with respect to the first SNP in the block. The transition score represents the probability of correctly determining the phase of a SNP with respect to the previous one. Finally, the emission score is often helpful in finding sequencing errors and other issues with the underlying data.

Whenever the transition score is too low, we suggest breaking the haplotype block at a position. Whenever the posterior or the emission scores are low, we suggest leaving that position unphased.

3.2 Comparison methodology

We compared ProbHap to three state-of-the art algorithms—RefHap (Duitama et al., 2010), FastHare (Panconesi and Sozio, 2004) and DGS (Panconesi and Sozio, 2004) as well as to HapCut (Bansal and Bafna, 2008), a historically important phasing package, and to MixSIH (Matsumoto and Kiryu, 2013), the only method that we know that produces confidence scores. Previous studies (Duitama et al., 2012; Geraci, 2010) have identified the above methods as being the current state-of-the-art in single-individual haplotype phasing.

Note that we do not compare our method to HapSeq (He et al., 2012) because this package additionally uses population-based statistical phasing techniques to improve accuracy. We also do not consider previously proposed exact dynamic programming methods (He et al., 2010), as they do not scale to long reads: their running time increases exponentially in the number of variants in a read, and some of the reads in our datasets have >50 variants.

The heuristics we consider work as follows. In brief, FastHare sorts the input reads, and then traverses this ordering once, greedily assigning each read to its most probable chromosome given what has been seen so far. The DGS method is equally simple: it iterates until convergence between assigning each fragment to its closest chromosome, and recomputing a set of consensus haplotypes. The RefHap and Hapcut algorithms construct a graph based where each vertex is either associated with a position (HapCut) or with a sequencing read (RefHap); then, the algorithms approximately solve a MaxCut problem on this graph.

We test the above methods on a long read dataset from HapMap sample NA12878 that was produced using a fosmid-based technology (Duitama et al., 2012). The long reads have an average length of ∼40 kb and cover the genome at a depth of ∼3×. This dataset is a standard benchmark for SIH algorithms (Duitama et al., 2012; Matsumoto and Kiryu, 2013) in part because HapMap sample NA12878 has also been phased multiple times based on the genomes of its parents. In this work, we take the trio-phased variant calls from the GATK resource bundle (DePristo et al., 2011); these provide accurate phase at 1 342 091 heterozygous variants that are also present in the long read dataset.

We measure performance using the concept of a switch error (Browning and Browning, 2011). A switch error is said to occur when the true parental provenance of SNPs on a haplotype changes with respect to the previous position. For example, if the true SNP origins of a phased block can be written as MMFF, then we say there is a switch error at the third position. In this analysis, we differentiate between two types of switches: a long switch corresponds to an inversion that lasts for more than one position (e.g. MMFF); a short switch, on the other hand, affects only a single position (e.g. MMFM). Switch accuracy is defined as the number of positions without switch errors, divided by the number of positions at which such errors could be measured. Long switch accuracy is defined accordingly in terms of long switch errors. We also measure accuracy in terms of switches per megabase (Sw./Mb).

Finally, a block N50 length of x signifies that at least 50% of all phased SNPs were placed within blocks containing x SNPs or more. The percentage of SNPs phased was defined as the number of SNPs in blocks of length two or more, divided by the total number of SNPs.

3.3 Results

Given comparable phasing rates and N50 block lengths, ProbHap produced haplotype blocks with more accurate long-range phase: the long-range switch error of ProbHap was 11% lower than that of the second best algorithm, RefHap (Table 1). In addition, ProbHap also produced 6% fewer short switch errors than RefHap.

Table 1.

Comparison of algorithm performance

| Algorithm | Long sw./Mb | Short sw./Mb | % phased | N50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProbHap | 1.07 | 3.70 | 91.83 | 227 |

| Refhap | 1.20 | 3.91 | 91.75 | 226 |

| FastHare | 1.32 | 4.03 | 91.76 | 227 |

| DGS | 1.48 | 4.18 | 91.66 | 227 |

| HapCut | 1.61 | 4.93 | 91.61 | 227 |

| MixSIH | 1.41 | 5.43 | 92.64 | 229 |

Note that long switch accuracy is substantially more important than short switch accuracy, as it drastically changes the global structure of haplotypes. Short switch errors, on the other hand, introduce relatively small amounts of noise in the data.

3.4 Evaluating confidence scores

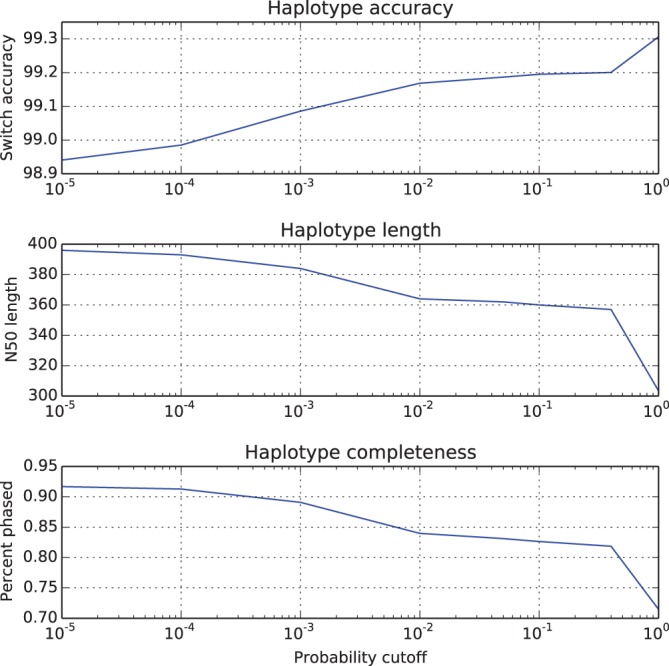

In addition to being more accurate, ProbHap is also one of the few algorithms which can provide estimates of their accuracy in the form of confidence scores. As an example of how such scores might be used, we pruned phased positions that were deemed by ProbHap to be uncertain and measured the resulting accuracy.

More specifically, we defined thresholds for each of the three confidence scores reported by ProbHap. Whenever the posterior or emission scores were lower than a threshold, we treated that position as unphased. Whenever the transition probability was below a threshold, we split the phased block into two parts at that position.

Figure 1 shows that after pruning, one obtains phased blocks that are 30–40% more accurate than the unpruned blocks (recall that we describe them in Table 1); the price to pay is a drop of 10–25% in N50 and phasing rate. The particular numbers shown in Figure 1 were achieved by fixing the posterior and transition cutoffs to 0.6 and , respectively, and setting the emission cutoff to , 0.05, 0.1, 0.4 and 0.99.

Fig. 1.

Accuracy/completeness trade-off for ProbHap

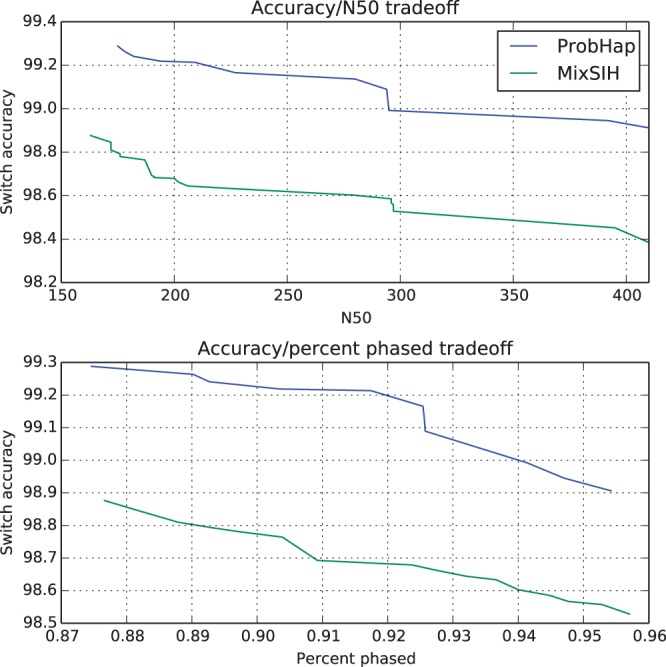

Next, we compared the pruned regions from ProbHap to those of MixSIH, the only other package that allows the user to exclude low-confidence positions. We chose thresholds so as to keep either the N50 or the phasing rate constant across both algorithms, and measured how accuracy varied with the remaining non-fixed parameter. We present the results of our experiment in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the accuracy/completeness trade-off of ProbHap and MixSIH. The top panel compares the trade-off between the N50 and the phasing accuracy; the phasing rate was the same for both algorithms at each point. Similarly, the bottom panel examines the phasing rate trade-off

Overall, we see that given the same level of haplotype completeness, the pruned blocks of ProbHap contain 20–30% fewer switching errors than those from MixSIH.

3.5 Running time

We measured the running times of the algorithms on a laptop computer (Table 2). We did not include HapCut in this comparison, as it is several orders of magnitude slower that the other methods (Duitama et al., 2012). Although the three heuristics ran faster than ProbHap and MixSIH, a major reason for their speed was due to not having to compute confidence scores. In fact, ProbHap spends roughly two-thirds of its running time computing such scores. Nonetheless, it phases chromosome 22 in just under a minute; the total time for phasing a human genome was under 30 minutes.

Table 2.

Running time of each algorithm on chromosome 22

| Refhap | FastHare | DGS | MixSIH | ProbHap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running time | 3.65 s | 1.85 s | 1.99 s | 274.82 s | 58.53 s |

4 METHODS

4.1 Notation

Formally, an instance of the sih problem is defined by a pair of n × m matrices M, Q, whose columns correspond to heterozygous positions (indexed by ), and whose rows correspond to reads (indexed by ). We refer to M as the phasing matrix; its entries take values in the set . These values indicate the allele carried by a read at a given position: for example, Mij = 0 signifies that read i covers position j and carries allele 0 at j. A value of – indicates that read i did not cover position j. See Table 3 for an example of a 2 × 4 phasing matrix.

Table 3.

Example of a 2 × 4 phasing matrix M, in which two reads cover three positions each

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Read 2 | – | 1 | 0 | 0 |

The n × m matrix is referred to as the q-score matrix; it encodes the probability of observing a sequencing error at a given position in a read. Such scores are available on virtually all sequencing platforms.

A solution to an instance of the sih problem consists of a pair of vectors and . The former determines the subject’s haplotypes: at each genomic position j, it specifies an allele . We consider only one haplotype, as the second is always the complement of the first. The second vector indicates the true provenance of each read i (i.e. whether i was obtained from the ‘maternal’ or the ‘paternal’ copy; because we do not have information to determine which copy comes from which parent, we refer to them as 0, 1). We also use

to denote alleles on the haplotype from which read i originated.

Next, let denote the set of positions covered by read i. Let also be the set of haplotype variables spanned by read i and let be the set of read provenance variables spanning a position j. We will use this notation to simplify several expressions throughout the article. In particular, if position j is spanned by, say, reads 2, 3, then we will use the notation and .

4.2 Probabilistic model

We define the probability over haplotypes , assignments of reads and observed data to be a product of factors

where

is the probability of observing the allele on the j-th position in read i, and the factors and are priors that we leave as uniform, except for . This last choice eliminates the ambiguity stemming from the fact that a solution h can be always replaced with its complement ; it resolves this ambiguity by always choosing the solution with . Finally, note that the r and h variables are hidden, while the o variables are observed; the observed values are defined by the matrix M.

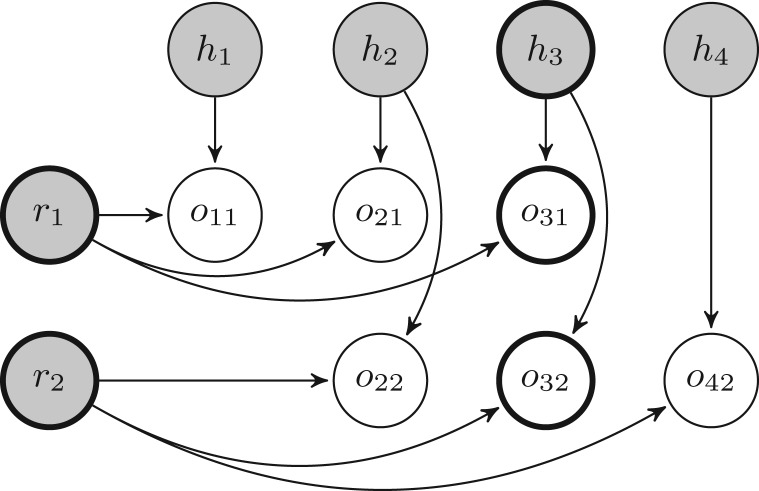

The dependency structure of P can be represented in terms of a Bayesian network whose topology mirrors the two-dimensional structure of the matrix M. See Figure 3 for the Bayesian network associated with the phasing matrix in Table 3, which we gave earlier as an example.

Fig. 3.

Bayesian network associated with the problem instance defined in Table 3. The shaded nodes represent hidden variables; unshaded variables are observed. Variables belonging to cluster C3 of the associated junction tree are shown in bold

4.3 Maximum likelihood haplotypes

We determine maximum-likelihood haplotypes using the belief propagation algorithm, also known as max-sum message passing over a junction tree (Koller and Friedman, 2009). In brief, this algorithm involves groups of variables passing each other information about their most likely assignment; a well-known special case of this method is the Viterbi algorithm for hidden Markov models (HMMs).

4.3.1 Definition of max-sum message passing

We start by briefly defining the max-sum message passing algorithm for graphical models. Readers familiar with the subject may skip this subsection.

Definition 1 —

Let P be a probability over a set of variables that is a product of k factors , with each factor being defined over a subset of variables . A junction tree T over P is a tree whose set of nodes is a family of subsets , with and that satisfies the following properties:

For each factor , there is a cluster c(i) such that .

(Running intersection) If and , then for all Ck on the unique path from Ci to Cj in T.

Given this definition, we now define max-sum message passing. We restrict our definition to the case when the junction tree T is a path, which is going to be the case for our model.

Definition 2 —

Let P be a probability distribution as in Definition 1. Let T be a junction tree over clusters Cj for connected into a path and ordered by j, with Cm serving as the root. The max-sum message from Cj to is a function Mj defined over the variables in as

with the additional definition that .

The max-sum message passing algorithm recursively computes the above messages and determines that is

The actual assignment that maximizes P can be found by storing the variable assignments that maximize each Mj. Unfortunately, proving the correctness of this algorithm is beyond the scope of this article. For a complete discussion that holds for arbitrary junction trees, we refer the reader to a textbook on graphical models (Koller and Friedman, 2009).

4.3.2 Applying max-sum message passing to the ProbHap model

We now define how the max-sum message passing algorithm is applied to the graphical model we defined in Section 4.2.

Definition 3 —

Let T be a junction tree for P defined by clusters

for connected into a path ordered by j, with Cm serving as the root.

Each cluster Cj contains hj and all the oij and ri variables associated with reads that span across position j. For an example of one such cluster, see Figure 3.

Lemma 1 —

The tree T in Definition 3 is a valid junction tree for the distribution P defined in Section 4.2.

Proof —

It is easy to check that the scope of each factor of P is in a unique cluster. We therefore focus on proving that T has the running intersection property.

Let Cx, Cy be two clusters in T with , and let Cz be a cluster on the path between Cx and Cy. Because T is a path, we must have . We need to show that .

Observe that by construction can only contain r-variables. Let be one such variable. We need to show that , i.e. that .

From , we have that . Because we also have , our claim follows.▪

Now let and . The interested reader may verify that the message from cluster j to cluster j + 1 during a run of max-sum message passing with Cm as the root of T equals for j > 1,

| (1) |

and for j = 1, . Note that we disregard the priors in all messages except the first because they are uniform.

Intuitively, represents the maximum likelihood of the data at positions assuming that reads spanning both j and j + 1 have provenances specified by . The maximum of P is computed using the recursion

4.3.3 Running time

The above algorithm computes one message for each of m. A message specifies a value for each assignment of variables in ; this value is the maximum over all assignments to hj and to , and for each such assignment, we need to compute in time. Therefore, computing a message requires iterations. Thus, the total running time of the algorithm is , where is the maximal coverage across all the positions.

4.4 Confidence scores

Next, we turn our attention to deriving confidence estimates for genomic regions. As an example of why such estimates are useful, we show in Table 4 that, somewhat counter-intuitively, two SNPs may be unphased even when they are connected by accurate reads.

Table 4.

Example of a sequencing error that confounds the long-range structure of the haplotypes

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Read 2 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note. If the quality scores are the same at all positions, the haplotypes h = 00000, h = 00111 have the same probability.

4.4.1 Motivating example

In Table 4, the data contains sequencing errors at position 3 or 4. If the error occurs at position 3 (in either row), then the two reads come from the same haplotype and the correct solution is h = 00000. If, on the other hand, the error occurs at position 4, then the two reads come from different chromosomes and the true haplotype is h = 00111. If the quality scores are the same at all positions, the four errors are equally likely, and the haplotypes h = 00000, h = 00111 have the same probability.

Simple optimization-based algorithms would likely produce a single haplotype in the above example; our probabilistic model, however, would assign a transition probability of 0.5 to position 3.

4.4.2 Dynamic programming recursion

We again perform probabilistic inference in our model using belief propagation. Our particular implementation of this method is inspired by the sum-product message passing algorithm (Koller and Friedman, 2009) over the previously defined junction tree T. In sum-product message passing, clusters of variables pass to each other information about their local probability distribution; after two rounds of message passing (referred to as ‘forwards’ and ‘backwards’), the clusters become calibrated and can be queried for various probabilities. A well-known special case of this method is the forwards–backwards algorithm for HMMs.

More concretely, we compute for each node j two factors, and , using the dynamic programming recursions below.

| (2) |

| (3) |

The notation indicates that the ri variables common to both Rj and have been assigned the same value, and is shorthand for . It follows from our definition of the prior that the initial values equal and ; in addition, .

It is easy to show by induction that

| (4) |

| (5) |

where .

4.4.3 Computing confidence probabilities

From (4), (5), we can now easily compute confidence scores. One such score is the posterior probability . It represents the probability that hj was determined correctly with respect to h1 and can be computed as , where

Next, the transition probability represents the probability of consecutive SNPs being phased correctly; it can be used to detect potential errors like the one shown in Table 4. We compute this value using the identity , where the denominator is the posterior probability and the numerator is computed as

where

Additionally, we found that the emission probability was useful in detecting errors in the data. Computing this value only involves the expression .

Finally, note that in general, one can compute any set of probabilities in the model. However, this involves doing potentially up to a full run of message passing.

4.5 A merging heuristic

The exact dynamic programming algorithm described above is practical for coverages of up to 10–12×. For deeper or for highly uneven coverages, we propose a simple preprocessing heuristic. The heuristic consists in reducing the coverage by repeatedly merging reads that are likely to come from the same haplotypes until there are no reads that we can confidently merge.

To determine whether to merge reads k, l, we consider the ratio

| (6) |

where is shorthand for . Intuitively, the denominator is associated with the likelihood that the two reads come from the same haplotype and the numerator is associated with the likelihood that the reads’ origins are different. Both terms are estimated by a heuristic formula that decomposes over each position. If reads k, l are merged, then position j of the resulting new read is assigned the allele that has the highest q-score in the initial reads k, l (i.e. ); the q-score at that position is set to the difference of the initial reads' q-scores (i.e. ).

In practice, one may select a confidence threshold for (6) and only merge reads that are below this threshold. We found empirically a value of to work well.

4.6 A post-processing heuristic

In addition, ProbHap admits an extra post-processing heuristic for adjusting the optimal haplotypes . This heuristic was initially proposed for the algorithm RefHap; ProbHap currently uses it by default, although it can be disabled. The heuristic starts with the optimal read assignments and determines at each position j a pair of sets

It then outputs a new haplotype defined as

We found that this heuristic increases the short switch accuracy of ProbHap on the NA12878 dataset; the long switch accuracy remains the same. We suggest using this heuristic in settings where the quality scores may not be well calibrated.

5 DISCUSSION: THEORETICAL ASPECTS

Interestingly, the probabilistic framework of ProbHap generalizes the sih formalism on which most existing methods are based. This allows us to easily derive well-known exact dynamic programming algorithms as special cases of the variable elimination algorithm for graphical models. More interestingly, the variable elimination algorithm with different variable orderings results in novel exact algorithms that are far more efficient than existing ones.

5.1 Generalizing the sih framework

In its standard formulation, the sih problem consists in finding a haplotype h that minimizes the MEC criterion:

where is the indicator function, and the remaining notation is the same as defined in the Section 4. The MEC measures the total number of positions within all the reads that need to be corrected to make the reads consistent with a haplotype h.

It is easy to show that the MEC objective can be recovered as a special case of our framework. Indeed, if we define the factors (which we have previously set to ) in a way that

then equals MEC(h, M), although P is no longer a probability.

Thus, our dynamic programming algorithms can also produce exact solutions to the MEC objective, and just as interestingly, they can produce confidence probabilities associated with the MEC.

5.2 Rederiving existing sih algorithms

Interestingly, we can easily recover an existing dynamic programming algorithm (He et al., 2010) for the MEC as a special case of variable elimination in our graphical model. Indeed, consider the junction tree defined by n variable clusters connected into a path ordered by i. If we assume for simplicity that the data have no contained reads, then the message from cluster i − 1 to cluster i during a run of max-sum message passing with Cn as the junction tree root equals precisely

| (7) |

where and . This is essentially the well-known dynamic programming recursion (He et al., 2010) we were looking to find.

Unfortunately, the time to compute the above recursion increases exponentially in the length of the reads, which is precisely the data we want to use for phasing.

5.3 Deriving novel sih algorithms

Fortunately, as we have seen, we can derive from our framework exact algorithms that are suitable for long read data. Interestingly, these methods are in a sense dual to equation (7): the structure of the probabilistic model P is entirely symmetric in r, h. If we reverse h and r in Section 4, we obtain recursion (7).

Potentially, our framework allows deriving other exact algorithms by defining alternative junction trees for the max-sum message passing algorithm. One way to do this involves using minimizing their tree-width using some well-known heuristics (Koller and Friedman, 2009). Because the running time max-sum message passing is exponential in the tree-width of a junction tree, this would lead to much faster running times.

6 CONCLUSION

In summary, we have introduced a new single-individual phasing algorithm, ProbHap, that offers an 11% improvement in accuracy over the current state-of-the-art method, RefHap. In addition, it is one of the only methods to provide the user with confidence scores at every position; these confidence scores can be used to prune positions whose phase is uncertain and thus substantially increase the overall accuracy.

The advances behind ProbHap are made possible by framing the phasing problem within a probabilistic graphical models framework. This framework makes it particularly easy to reason about the problem; in fact, all our algorithms are special cases of standard procedures for optimizing graphical models.

On the theoretical side, this work generalizes the MEC criterion used by existing methods. Our approach allows us to obtain existing algorithms as special cases of well-known optimization procedures, and also easily derive new, more efficient algorithms; it may thus serve as a foundation for further algorithmic insights.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Sivan Berovici for important suggestions regarding the model definition, as well as Dmitry Pushkarev and Michael Kertesz for helpful discussions. This research was partly done at Moleculo Inc.

Funding: This work was partly funded by NIH/NHGRI grant T32 HG000044.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bansal V, Bafna V. HapCUT: an efficient and accurate algorithm for the haplotype assembly problem. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i153–i159. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal V, et al. An MCMC algorithm for haplotype assembly from whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 2008;18:1336–1346. doi: 10.1101/gr.077065.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning SR, Browning BL. Haplotype phasing: existing methods and new developments. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duitama J, et al. Proceedings of the First ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010. ReFHap: a reliable and fast algorithm for single individual haplotyping; pp. 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Duitama J, et al. Fosmid-based whole genome haplotyping of a HapMap trio child: evaluation of Single Individual Haplotyping techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2041–2053. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci F. A comparison of several algorithms for the single individual SNP haplotyping reconstruction problem. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2217–2225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield D. Inference of haplotypes from samples of diploid populations: complexity and algorithms. J. Comput. Biol. 2001;8:305–323. doi: 10.1089/10665270152530863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D, et al. Optimal algorithms for haplotype assembly from whole-genome sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i183–i190. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D, et al. RECOMB’12: Proceedings of the 16th Annual international conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2012. Hap-seq: an optimal algorithm for haplotype phasing with imputation using sequencing data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper F, et al. Whole-genome haplotyping by dilution, amplification, and sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5552–5557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218696110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, et al. Diploid genome reconstruction of Ciona intestinalis and comparative analysis with Ciona savignyi. Genome Res. 2007;17:1101–1110. doi: 10.1101/gr.5894107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman JO, et al. Haplotype-resolved genome sequencing of a Gujarati Indian individual. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;29:59–63. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller D, Friedman N. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques - Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lippert R, et al. Algorithmic strategies for the single nucleotide polymorphism haplotype assembly problem. Brief. Bioinformatics. 2002;3:23–31. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Kiryu H. MixSIH: a mixture model for single individual haplotyping. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(Suppl. 2):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S2-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panconesi A, Sozio M. Fast hare: a fast heuristic for single individual snp haplotype reconstruction. In: Jonassen I, Kim J, editors. Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. pp. 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Peters BA, et al. Accurate whole-genome sequencing and haplotyping from 10 to 20 human cells. Nature. 2012;487:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature11236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskoboynik A, et al. The genome sequence of the colonial chordate, Botryllus schlosseri. eLife. 2013;2:e00569. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]