Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS) are a mixture of more than 100 glycans which constitute the third major component of human milk.[1] They have been found to contribute significantly to the gut health of breastfed infants. Strong evidences are available now to support the roles of HMOS on promoting the growth of beneficial gut bacteria; inhibiting the binding of pathogenic bacteria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or protozoan parasites to gut epithelial cells; modulating immune responses; and influencing the functions of gut epithelium.[2]

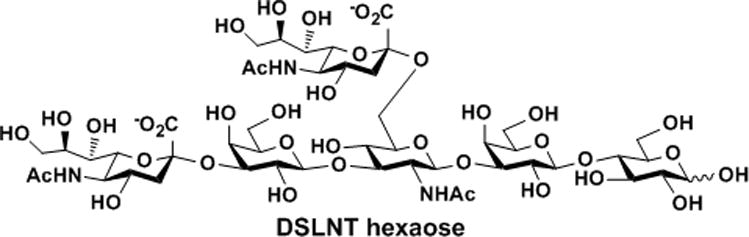

Most of the reported HMOS-related studies used HMOS mixtures and thus the key active components are not clear. Among a few individual HMOS with known functions, disialyllacto-N-tetraose (DSLNT, Figure 1), but not its non-sialylated or mono-sialylated analog, was previously identified as a specific HMOS component that is effective for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in a neonatal rat model.[3] DSLNT contains two sialic acid residues: one is linked to the terminal galactose (Gal) residue via an α2–3-sialyl linkage; the other is linked to the internal N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residue via an α2–6-sialyl linkage (Figure 1). The hexasaccharide is presented at a level of 0.2–0.6 gram in a liter of human milk.[4] However, it is not presented in porcine milk,[5] and either is not presented[6] or exists only in trace amount in bovine milk.[4, 7] Due to the limited availability of human milk and the absence or the low abundance of DSLNT in bovine milk, it is impractical to obtain the compound in large scale for potential clinical therapeutic applications. Furthermore, despite the identification of the activity of an α2–6-sialyltransferase (e.g. in the livers of various animals and human as well as in human placenta, bovine mammary gland, human milk, and human mammary tumor although at a lower level)that catalyzes transfer of sialic acid α2–6-linked to the internal GlcNAc residue in DSLNT,[8] the gene for the enzyme has not been identified. Therefore, it is currently unfeasible to obtain the desired α2–6-sialyltransferase in large amount to allow large-scale enzymatic synthesis of DSLNT. On the other hand, sialosides remain to be challenging targets for large scale chemical synthesis due to the intrinsic structural feature of sialic acids (e.g. steric hindered anomeric carbon with a connecting electron-withdrawing carboxyl group in the sialic acid which lowers the glycosylation reactivity and efficiency and the lack of a neighbouring participating group that disallows the precise control of the sialylation stereospecificity).[9] Recent advances in the development of chemical methods for synthesizing sialosides overcame some of the challenges and significantly improved synthetic yields and stereoselectivity. Nevertheless, despite the synthesis of a more complex DSLNT-containing glycosyl ceramide (35 mg)reported by the Kiso group,[10] chemical synthesis of DSLNT in a free oligosaccharide form has not been reported.

Figure 1.

The structure of disialyllacto-N-tetraose (DSLNT).

One strategy to overcome the challenges in obtaining DSLNT in a large amount for NEC studies and potential therapies is to identify compounds that have similar or better NEC-preventing effects than DSLNT and can be easily obtained synthetically. Here, we report that two novel synthetic disialyl hexasaccharides, including α2–6-linked disialyllacto-N-neotetraose (DSLNnT) obtained by sequential one-pot multienzyme (OPME) reactions and α2–6-linked disialyllacto-N-tetraose (DS’LNT) obtained by one-pot sialylation of lacto-N-tetraose (LNT), have potent NEC-preventing effect. DSLNnT can be produced in a large amount from simple starting materials for potential therapeutic applications.

In nature, the key enzymes that catalyze the glycosidic bond formation are glycosyltransferases (GlyT). GlyT-catalyzed transfer of monosaccharides other than sialic acids can be achieved most efficiently via a three-enzyme process: activation of a monosaccharide by a glycokinase (GlyK) to form a sugar-1-phosphate (monosaccharide-1-P), which can be used by a nucleotidyltransferase (NucT) for the synthesis of a nucleoside diphosphate monosaccharide, the sugar nucleotide donor substrate of a suitable glycosyltransferase (GlyT) for the formation of a desired glycosidic bond in the product.[11] An inorganic pyrophosphatase (PpA) can also be added to push the reaction towards completion in the direction of product formation.[12] These enzymes can be used in one-pot (so called OPME) for efficient synthesis of glycans. Each OPME reaction is usually used to add one monosaccharide to a glycosyltransferase acceptor. Carrying out the OPME reactions sequentially allows the formation of complex carbohydrates and glycoconjugates. The stereo- and regiospecificities of the glycosidic bond formed, the nucleotide triphosphate required, and the selection of related sugar nucleotide biosynthetic enzymes are defined by the glycosyltransferases chosen based on the structures of the desired carbohydrate products. As OPME approaches are limited by the availability, expression level, solubility, stability for storage, and substrate specificity of the enzymes involved, identifying suitable glycosyltransferases and the corresponding sugar nucleotide biosynthetic enzymes is critical for developing efficient OPME systems.

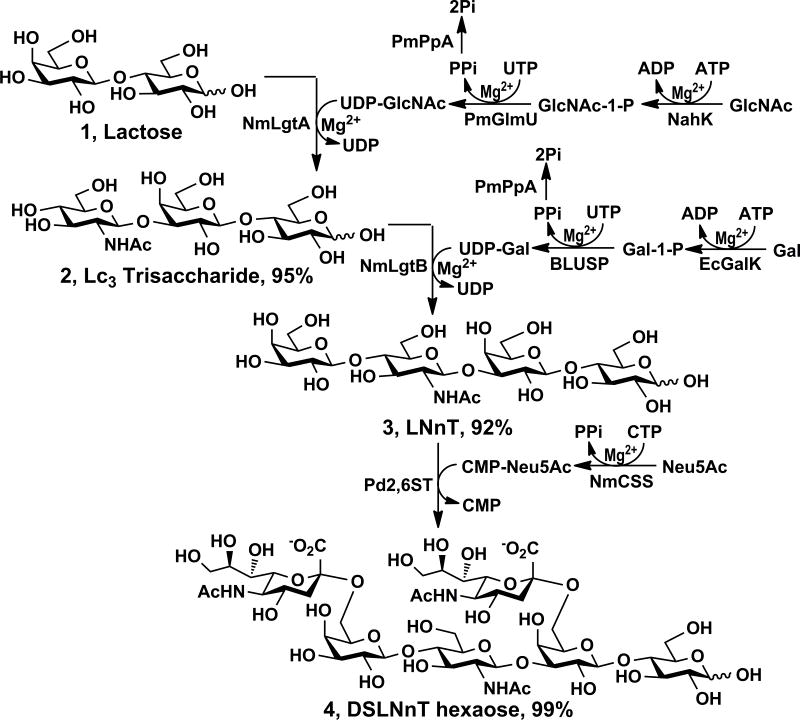

To obtain lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT), a common human milk tetrasaccharide (3), Lc3 trisaccharide GlcNAcβ1–3Galβ1–4Glc (2) (Scheme 1) was synthesized from inexpensive disaccharide lactose (1) and monosaccharide N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) using a one-pot four-enzyme GlcNAc activation and transfer system containing Bifidobacterium longum strain ATCC55813 N–acetylhexosamine-1-kinase (NahK),[13] Pasteurella multocida N-acetylglucosamine uridyltransferase (PmGlmU),[14] Pasteurella multocida inorganic pyrophosphatase (PmPpA),[12] and Neisseria meningitidis β1–3-N–acetylglucosaminyltransferase (NmLgtA).[15] In this system, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) and GlcNAc were used by NahK-catalyzed reaction to form GlcNAc-1-P, which was used with uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP) by PmGlmU to form UDP-GlcNAc, the sugar nucleotide donor for NmLgtA for the production of Lc3 from lactose. All four enzymes were quite active in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.0 and Lc3 trisaccharide (1.36 g) was obtained in an excellent yield (95%) by incubation at 37 °C for 2 days.

Scheme 1.

Sequential one-pot multienzyme (OPME) synthesis of lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) and DSLNnT. Enzymes: NahK, N–acetylhexosamine-1-kinase; PmGlmU, Pasteurella multocida N-acetylglucosamine uridyltransferase; PmPpA, a Pasteurella multocida inorganic pyrophosphatase; NmLgtA, β1–3-N–acetylglucosaminyltransferase; EcGalK, Escherichia coli galactokinase; BLUSP, Bifidobacterium longum UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase; NmLgtB, Neisseria meningitidis β1–4-galactosyltransferase; NmCSS, Neisseria meningitidis CMP-sialic acid synthetase; Pd2,6ST, Photobacterium damselae α2–6-sialyltransferase.

Taking advantage of a promiscuous Bifidobacterium longum UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase (BLUSP)[16] which can produce uridine 5′-diphosphate galactose (UDP-Gal) directly from UTP and galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1-P), LNnT Galβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–3Galβ1–4Glc (3) (1.19 g) was synthesized from Lc3 (2) and a simple galactose (Gal) in an excellent yield (92%) using a one-pot four-enzyme galactosylation system[17] containing Escherichia coli galactokinase (EcGalK),[18] BLUSP,[16] PmPpA,[12] and Neisseria meningitidis β1–4-galactosyltransferase (NmLgtB).[12] This is a more effective system compared to our previously reported OPME β1–4-galactosylation process which involved the formation of UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc) from glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) followed by C4-epimerization to produce UDP-Gal indirectly.[12]

Initial sialylation of LNnT using N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) in a one-pot two-enzyme sialylation system[19] containing Neisseria meningitidis CMP-sialic acid synthetase (NmCSS)[19a] and Photobacterium damselae α2–6-sialyltransferase (Pd2,6ST)[20] with an Neu5Ac to LNnT ratio of 1.5 to 1 produced an unexpected mixture of mono-sialylated and disialyl LNnT (DSLNnT) which were difficult to separate. Increasing the Neu5Ac to LNnT ratio to 2.4 to 1 led to the formation of DSLNnT hexasaccharide Neu5Acα2–6Galβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–3(Neu5Acα2–6)Galβ1–4Glc (4) (236 mg)in an excellent yield (99%). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data confirmed that Pd2,6ST does not only add a Neu5Ac α2–6-linked to the terminal Gal, it also adds an α2–6-linked Neu5Ac to the internal Gal residue in LNnT which is in consistent with the observation in a recent report.[21] As shown in Table 1 using the beta-anomers (the major forms in D2O solution) of the glycans for comparison, the attachment of Neu5Ac to the C-6 of the internal Gal (GalII) and the terminal Gal (GalIV) in LNnT results in significant downfield shifts of the substituted carbons (a downfield shift of 2.39 ppm for the C-6 of GalII and a downfield shift of 2.52 ppm for the C-6 of GalIV) in DSLNnT. There are obvious interactions of the Neu5Ac residues and GlcNAcIII and GlcI which result in a significant downfield shift of 2.58 ppm for the C-4 of GlcNAcIII and a downfield shift of 1.55 ppm for the C-4 of GlcI. These unusual chemical shift changes seen in Neu5Acα2–6Gal sialosides are in accordance with those observed for the glycans with same or similar structural element.[22]

Table 1.

13C NMR chemical shifts for compounds Galβ1–4Glc (Lac), GlcNAcβ1–3Galβ1–4Glc (Lc3 glycan), Galβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–3Galβ1–4Glc (LNnT), and Neu5Acα2–6Galβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–3(Neu5Acα2–6)Galβ1–4Glc (DSLNnT). Significant chemical shift changes after sialylation for the formation of DSLNnT from LNnT are highlighted in bold.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sugar Unit | Carbon atoms | Lac | Lc3 glycan | LNnT | DSLNnT |

| β-D-GlcI | 1 | 95.64 | 95.66 | 95.61 | 95.70 |

| 2 | 73.70 | 73.71 | 73.65 | 73.37 | |

| 3 | 74.26 | 74.20 | 74.22 | 74.36 | |

| 4 | 78.19 | 78.21 | 78.21 | 79.76 | |

| 5 | 74.69 | 74.71 | 74.76 | 74.76 | |

| 6 | 59.78 | 60.01 | 60.34 | 60.23 | |

| β-D-GalII(1–4) | 1 | 102.79 | 102.84 | 102.76 | 103.35 |

| 2 | 70.86 | 70.03 | 69.88 | 69.76 | |

| 3 | 72.42 | 81.87 | 81.82 | 82.29 | |

| 4 | 68.46 | 68.26 | 68.22 | 68.32 | |

| 5 | 75.25 | 74.80 | 75.52 | 73.77 | |

| 6 | 60.94 | 60.88 | 60.84 | 63.23 | |

| β-D-GlcNAcIII(1–3) | 1 | 102.75 | 102.73 | 102.74 | |

| 2 | 56.58 | 56.52 | 54.83 | ||

| 3 | 73.49 | 73.42 | 72.50 | ||

| 4 | 69.92 | 78.11 | 80.69 | ||

| 5 | 75.57 | 74.66 | 74.72 | ||

| 6 | 60.41 | 59.93 | 60.05 | ||

| C=O | 174.87 | 174.83 | 175.01 | ||

| CH3 | 22.09 | 22.03 | 22.38 | ||

| β-D-GalIV(1–4) | 1 | 102.79 | 103.65 | ||

| 2 | 70.99 | 70.83 | |||

| 3 | 73.42 | 72.62 | |||

| 4 | 68.24 | 68.47 | |||

| 5 | 75.52 | 73.80 | |||

| 6 | 60.85 | 63.37 | |||

| α-D-Neu5AcV(2–6) | 1 | 173.59 | |||

| 2 | 100.38 | ||||

| 3 | 40.17 | ||||

| 4 | 68.47 | ||||

| 5 | 51.69 | ||||

| 6 | 72.64 | ||||

| 7 | 68.50 | ||||

| 8 | 71.86 | ||||

| 9 | 62.53 | ||||

| C=O | 175.01 | ||||

| CH3 | 22.12 | ||||

| α-D-Neu5AcVI(2–6) | 1 | 173.66 | |||

| 2 | 100.23 | ||||

| 3 | 40.17 | ||||

| 4 | 68.47 | ||||

| 5 | 51.79 | ||||

| 6 | 72.64 | ||||

| 7 | 68.50 | ||||

| 8 | 71.81 | ||||

| 9 | 62.53 | ||||

| C=O | 175.01 | ||||

| CH3 | 22.15 | ||||

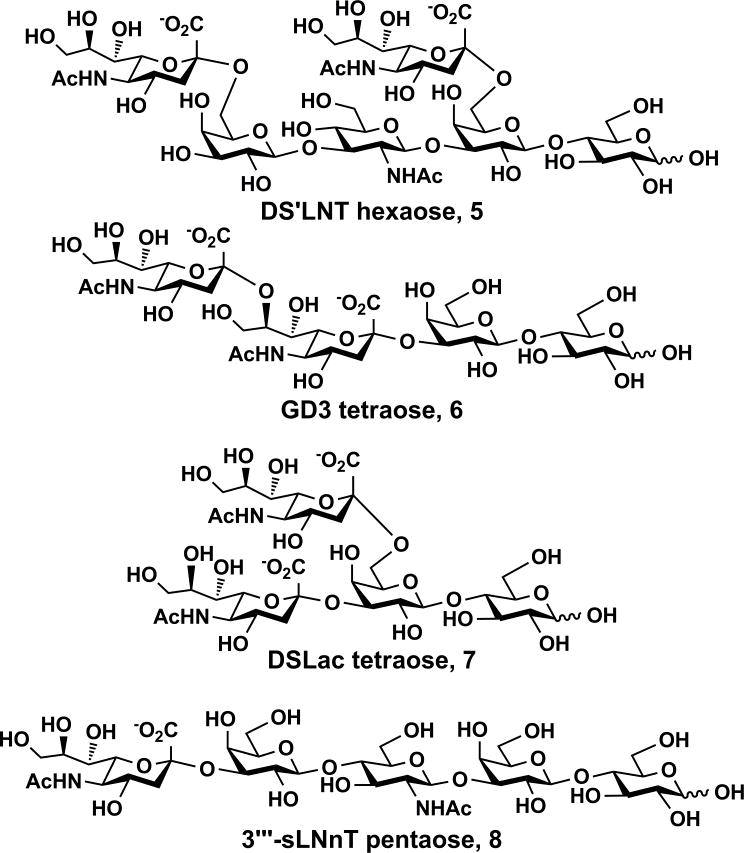

Disialyl LNT (DS’LNT) hexaose (Figure 2) Neu5Acα2–6Galβ1–3GlcNAcβ1–3(Neu5Acα2–6)Galβ1–4Glc (5) (268 mg) containing two sialic acid residues α2–6-linked to the terminal and internal Gal residues of LNT, respectively, was also synthesized in an excellent yield (98%) using the same one-pot two-enzyme sialylation system containing NmCSS and Pd2,6ST with an Neu5Ac to LNT ratio of 2.6 to 1.

Figure 2.

Structures of DS’LNT hexaose, GD3 tetraose, and DSLac tetraose.

Two other disialyl glycans (Figure 2) including GD3 tetrasaccharide Neu5Acα2–8Neu5Acα2–3Galβ1–4Glc (6) (239 mg), and disialyllactose (DSLac) Neu5Acα2–3(Neu5Acα2–6)Galβ1–4Glc (7) (112 mg) were also synthesized, from Neu5Acα2–3Lac,[23] using a one-pot two-enzyme sialylation system containing NmCSS and Campylobacter jejuni α2–3/8-sialyltransferase (CjCstII; for GD3)[24] or NmCSS and Pd2,6ST (for DSLac)[20] (see SI for details).

As a control, a monosialyl pentasaccharide 3‴-sialyl LNnT (3‴-sLNnT) (8) (138 mg) (Figure 2) was synthesized from LNnT (3) using a one-pot two-enzyme sialylation system using NmCSS and a single-site mutant of Pasteurella multocida multifunctional α2–3-sialyltransferase 1 (PmST1 M144D).[25] Unlike Pd2, 6ST-catalyzed sialylation reaction which could add either one or two α2–6-linked sialic acid residues to LNnT, PmST1 M144D-catalyzed sialylation reaction only added one α2–3-linked sialic acid residue to the terminal Gal in LNnT. The use of PmST1 M144D mutant[25] instead of the wild-type PmST1[23] avoided the product hydrolysis by the α2–3-sialidase activity of the wild-type enzyme, thus improved the yield of the one-pot two-enzyme α2–3-sialylation reaction. Indeed, an excellent yield (98%) was achieved without the need of close monitoring and stopping the reaction process promptly.

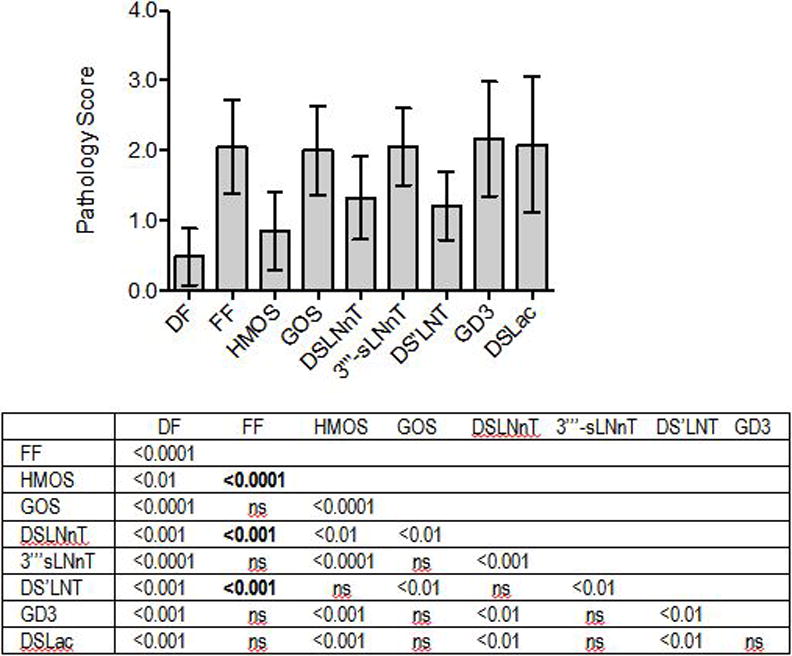

The NEC-preventing effects of disialyl compounds DSLNnT (4), DS’LNT (5), GD3 (6), DSLac (7), and monosialyl compound 3‴-sLNnT (8) were tested in the same neonatal rat model that was used previously.[3] A mixture of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS) isolated from pooled human milk was used as a positive intervention control and a galactooligosaccharides (GOS) sample, shown to be ineffective in preventing NEC,[3] was used as negative intervention control. As shown in Figure 3, dam-fed (DF) animals hardly developed any signs of NEC (mean pathology score 0.48±0.41). Pathology scores were significantly higher in animals that were orally gavaged with rodent formula (FF) without the addition of glycans (2.06±0.67, p<0.0001 compared to DF). Adding HMOS to the formula led to significantly lower pathology scores (0.85±0.55, p<0.0001 compared to FF), which were not significantly different from the DF control (p=0.106). Adding GOS had no effect on lowering pathology scores (2.00±0.63, p=0.790 compared to FF). All these results are in accordance with the previously reported data.[3] Adding the synthesized DSLNnT to the formula led to significantly lower pathology scores (1.32±0.59, p<0.001 compared to FF), which was not significantly different from the effects seen in animals that received HMOS (p=0.062), but still different from the DF control (p<0.001). Adding the synthesized 3‴-sLNnT to the formula did not lower pathology scores (2.05±.55, p=0.987 compared to FF). Adding the synthesized DS’LNT to the formula significantly reduced pathology scores (1.21±0.49, p<0.001 compared to FF), which again was not significantly different from the effects seen in animals receiving HMOS (p=0.120), but still different from the DF control (p<0.001). Neither GD3 nor DSLac had a significant effect on pathology scores compared to animals that received formula alone.

Figure 3.

DSLNnT and DS’LNT protect neonatal rats from necrotizing enterocolitis. Ileum pathology scores (0: healthy; 4: complete destruction) are plotted for each animal in the different intervention groups. DF: dam fed (number of rats n=33); FF: fed formula without additional glycans (n=27); HMOS: FF contains oligosaccharides isolated from pooled human milk (2 mg/mL, n=23); GOS: FF contains galactooligosaccharides (2 mg/mL, n=15); DSLNnT: FF contains DSLNnT (300 μg/mL, n=20); 3‴-sLNnT: FF contains 3‴-sLNnT (300 μg/mL, n=19). DS’LNT: FF contains DS’LNT (300 μg/mL, n=14); GD3: FF contains GD3 (300 μg/mL, n=12); DSLac: FF contains DSLac (300 μg/mL, n=11). Bars represent mean±standard deviation. p values are listed in the table below the figure. ns: not significant.

These results show that similar to DSLNT, DSLNnT and DS’LNT reduce pathology scores in an NEC neonatal rat model. All three compounds are disialyl hexasaccharides but with noticeable structural differences. Firstly, both DSLNT and DS’LNT are disialyl type I glycans whose core tetrasaccharide (LNT) has a Gal residue β1–3-linked to Lc3 trisaccharide, while DSLNnT is a disialyl type II glycan whose core tetrasaccharide (LNnT) has a Gal residue β1–4-linked to the Lc3 trisaccharide. Secondarily, all three have a Neu5Acα2–6-linked to an internal monosaccharide, the internal monosaccharide is GlcNAc in DSLNT while a Gal in DSLNnT and DS’LNT. Thirdly, the outermost Neu5Ac is linked to the penultimate Gal in an α2–3-linkage in DSLNT but an α2–6-linkage in DSLNnT and DS’LNT. These structural differences of DSLNT, DSLNnT, and DS’LNT and their similarity in protecting neonatal rats from NEC indicate that the negatively charged disialyl component is important for the NEC preventing effect while the tetrasaccharide scaffold (type I or type II) does not seem to be important. The importance of disialyl component is further supported by the lacking of NEC preventing effect by monosialyl pentasaccharides such as LSTb[3] shown previously and 3‴-sLNnT shown here. However, the presence of disialyl component alone is not sufficient to explain the beneficial effects as GD3 and DSLac showed no effect.

In conclusion, we have shown here that novel synthetic disialyl hexasaccharides, including disialyllacto-N-neotetraose (DSLNnT) and α2–6-linked disialyllacto-N-tetraose (DS’LNT), can protect neonatal rats from NEC. Unlike the NEC-preventing DSLNT previously identified from human milk which is not easily obtainable by either purification or synthesis, the newly identified DSLNnT and DS’LNT are readily available by enzymatic synthesis. The sequential OPME systems described here allow the use of an inexpensive disaccharide and simple monosaccharides to synthesize desired complex oligosaccharide such as DSLNnT with high efficiency and selectivity. The readily available DSLNnT and DS’LNT are good therapeutic candidates for pre-clinical experiments and clinical application in treating NEC in preterm infants.

Experimental Section

Oligosaccharides 2–8 were prepared using one-pot multienzyme (OPME) reactions. Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee at the University of California, San Diego, AAALAC accreditation number 000503. Detailed synthetic procedures, NMR and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) characterization of the products including NMR spectra, and procedures for rat studies are available in the supporting information.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors thank Prof. Peng George Wang at the Georgia State University for providing the plasmid expressing recombinant NmLgtA and Liwen Deng at the Mouse Phenotyping Core, University of California, San Diego for tissue preparation, sectioning and H&E staining. This work was supported by NIH grant R01HD065122 (to X.C.) and NIH grant R00DK078668 (to L.B.). X.C. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar and a UC-Davis Chancellor’s Fellow. Bruker Avance-800 NMR spectrometer was funded by NSF grant DBIO-722538.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx.

Contributor Information

Hai Yu, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Kam Lau, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Vireak Thon, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Chloe A. Autran, Division of Neonatology and Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, University of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA)

Evelyn Jantscher-Krenn, Division of Neonatology and Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, University of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA).

Mengyang Xue, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA), National Glycoengineering Research Center, College of Life Sciences, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250100 (China).

Yanhong Li, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Go Sugiarto, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Jingyao Qu, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Shengmao Mu, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Li Ding, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

Lars Bode, Division of Neonatology and Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, University of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA).

Xi Chen, Email: xiichen@ucdavis.edu, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616 (USA).

References

- 1.Rudloff S, Kunz C. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:398S–405S. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Newburg DS, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:37–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bode L. Glycobiology. 2012;22:1147–1162. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chichlowski M, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2011;2:331–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022510-133743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jantscher-Krenn E, Zherebtsov M, Nissan C, Goth K, Guner YS, Naidu N, Choudhury B, Grishin AV, Ford HR, Bode L. Gut. 2012;61:1417–1425. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunz C, Rudloff S, Baier W, Klein N, Strobel S. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:699–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao N, Ochonicky KL, German JB, Donovan SM, Lebrilla CB. J Agri Food Chem. 2010;58:4653–4659. doi: 10.1021/jf100398u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Tao N, DePeters EJ, Freeman S, German JB, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:3768–3778. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Aldredge DL, Geronimo MR, Hua S, Nwosu CC, Lebrilla CB, Barile D. Glycobiology. 2013;23:664–676. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi P, Warren CD, Altaye M, Morrow AL, Ruiz-Palacios G, Pickering LK, Newburg DS. Glycobiology. 2001;11:365–372. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Heij HT, Koppen PL, van den Eijnden DH. Carbohydr Res. 1986;149:85–99. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Chen X, Varki A. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:163–176. doi: 10.1021/cb900266r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boons GJ, Demchenko AV. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4539–4566. doi: 10.1021/cr990313g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Adak AK, Yu CC, Liang CF, Lin CC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:1030–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ando T, Ishida H, Kiso M. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(02)00465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:14–17. doi: 10.1021/cb100375y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau K, Thon V, Yu H, Ding L, Chen Y, Muthana MM, Wong D, Huang R, Chen X. Chem Commun. 2010;46:6066–6068. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01381a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Yu H, Chen Y, Lau K, Cai L, Cao H, Tiwari VK, Qu J, Thon V, Wang PG, Chen X. Molecules. 2011;16:6396–6407. doi: 10.3390/molecules16086396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Thon V, Li Y, Yu H, Ding L, Lau K, Qu J, Hie L, Chen X. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10815–10817. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14034e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Guan W, Ban L, Cai L, Li L, Chen W, Liu X, Mrksich M, Wang PG. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5025–5028. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Blixt O, van Die I, Norberg T, van den Eijnden DH. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1061–1071. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.10.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthana MM, Qu J, Li Y, Zhang L, Yu H, Ding L, Malekan H, Chen X. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2728–2730. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17577k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malekan H, Fung G, Thon V, Khedri Z, Yu H, Qu J, Li Y, Ding L, Lam KS, Chen X. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:4778–4785. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Liu Z, Zhang J, Zhang W, Kowal P, Wang PG. Chembiochem. 2002;3:47–53. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020104)3:1<47::AID-CBIC47>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Yu H, Yu H, Karpel R, Chen X. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:6427–6435. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li Y, Yu H, Cao H, Lau K, Muthana S, Tiwari VK, Son B, Chen X. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;79:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1506-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Huang S, Chokhawala H, Sun M, Zheng H, Chen X. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3938–3944. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nycholat CM, Peng W, McBride R, Antonopoulos A, de Vries RP, Polonskaya Z, Finn MG, Dell A, Haslam SM, Paulson JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18280–18283. doi: 10.1021/ja409781c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Strecker G, Wieruszeski JM, Michalski JC, Montreuil J. Glycoconj J. 1989;6:67–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01047891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sabesan S, Bock K, Paulson JC. Carbohydr Res. 1991;218:27–54. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)84084-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu H, Chokhawala H, Karpel R, Yu H, Wu B, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Jia Q, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17618–17619. doi: 10.1021/ja0561690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Cheng J, Yu H, Lau K, Huang S, Chokhawala HA, Li Y, Tiwari VK, Chen X. Glycobiology. 2008;18:686–697. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu H, Cheng J, Ding L, Khedri Z, Chen Y, Chin S, Lau K, Tiwari VK, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18467–18477. doi: 10.1021/ja907750r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiarto G, Lau K, Qu J, Li Y, Lim S, Mu S, Ames JB, Fisher AJ, Chen X. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1232–1240. doi: 10.1021/cb300125k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.