Abstract

A growing number of publications supports a biologic effect of the protein-bound uremic retention solutes indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate. However, the use of unrealistically high free concentrations of these compounds and/or inappropriately low albumin concentrations may blur the interpretation of these results. Here, we performed a systematic review, selecting only studies in which, depending on the albumin concentration, real or extrapolated free concentrations of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate remained in the uremic range. The 27 studies retrieved comprised in vitro and animal studies. A quality score was developed, giving 1 point for each of the following criteria: six or more experiments, confirmation by more than one experimental approach, neutralization of the biologic effect by counteractive reagents or antibodies, use of a real-life model, and use of dose–response analyses in vitro and/or animal studies. The overall average score was 3 of 5 points, with five studies scoring 5 of 5 points and six studies scoring 4 of 5 points, highlighting the superior quality of a substantial number of the retrieved studies. In the 11 highest scoring studies, most functional deteriorations were related to uremic cardiovascular disease and kidney damage. We conclude that our systematic approach allowed the retrieval of methodologically correct studies unbiased by erroneous conditions related to albumin binding. Our data seem to confirm the toxicity of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate and support their roles in vascular and renal disease progression.

Keywords: CKD, uremic toxins, signaling, indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl, sulfate

As CKD evolves, uremic retention becomes a progressively more important contributor to overall organ dysfunction.1–3 Among the three physicochemical types of uremic solutes,4 the pathophysiologic importance of protein-bound toxins has been neglected for a long time,5–7 leading to a shortage of specific removal strategies.8,9 In the past decade, however, a growing number of publications documented the impact of protein-bound uremic toxins on vital processes and an association of their concentration with clinical outcome parameters.6,10–19

One factor blurring the interpretation of the biochemical effects of uremic toxins is the application of unrealistic concentrations compared with the concentrations observed in human CKD in in vitro testing or in vivo animal experiments.4,20 Moreover, for protein-bound toxins, even with seemingly acceptable total concentrations, the quantities of albumin or protein present are often too low, resulting in unacceptably high and thus, irrelevant free concentrations.

In analogy to drugs, albumin is likely to act as a buffer, attenuating potential biochemical effects of its ligands,21–23 whereas recent data clearly showed that, for both indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, albumin is the main binding protein.24

Absence of appropriate albumin quantities results in too high free solute concentrations, inducing exaggerated biologic responses with a potential for an overestimated toxic impact. This bias has provoked justified objections against recognizing protein-bound molecules as real uremic toxins. In a recent editorial,25 indoxyl sulfate, one of the main protein-bound solutes, was for that reason called “long suspected but not yet guilty.”

Nevertheless, a careful check of the literature reveals that investigators in a number of studies have applied acceptable free concentrations by administering those toxins to animals up to acceptable total concentrations, adding relevant quantities of albumin to in vitro media by using whole blood, plasma, or serum, or in the absence of albumin, applying concentrations corresponding to the free uremic fraction. At this moment, it is unclear, however, how many methodologically suitable publications are available and what they teach us about the contribution of the compounds to the uremic syndrome.

In the present analysis, we applied a systematic search to filter out those studies in which unacceptably high free concentration of protein-bound solutes had been applied. We aimed to analyze the effect of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate in vitro and in animals. Based on preset standards, 27 articles of adequate quality were retrieved and are reported here together with the shown effects.

Results

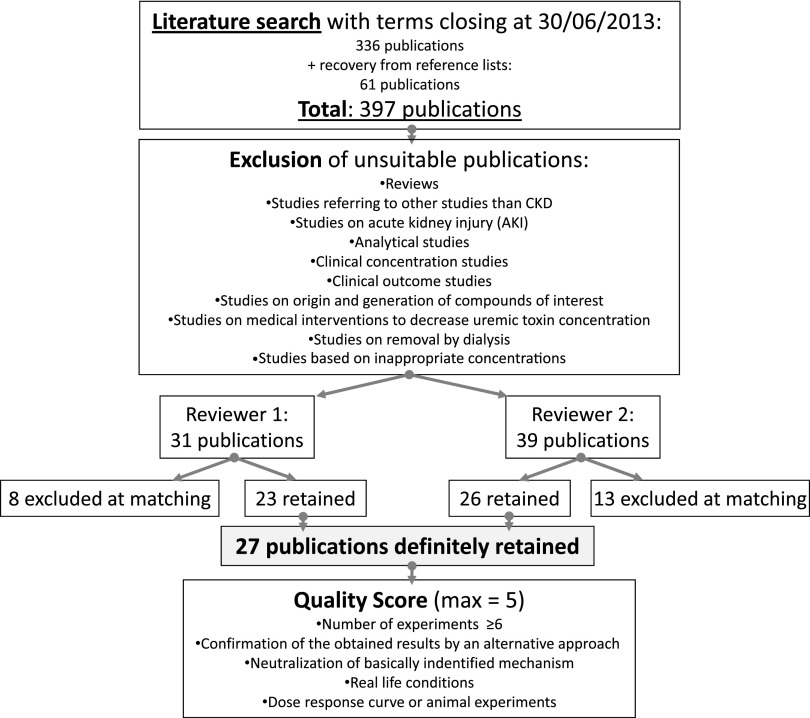

The literature was searched according to preset methods (see below) to retrieve studies on biologically relevant toxic effects of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate following well defined quality standards. One of the conditions was that the concentrations used in those studies conformed with the concentrations observed in uremia, which is illustrated in Table 1. The concentrations considered appropriate were in the high uremic range to compensate for the often short exposure time in the experimental studies, especially in vitro. To make a comparison with the values currently observed in an average dialysis population, we give in Table 1, also as reference, data retrieved from a recent study from the European Uremic Toxin Work Group as a real-life orientation for the reader.20 We identified 336 citations through electronic searching and added 61 citations from reference lists of retrieved publications (Figure 1). Based on the selection criteria, we included 27 studies in the review (Table 2).26–52

Table 1.

Threshold values of concentration

| Normal (mg/L) | Uremia (mg/L) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IS (molecular weight 212) | |||

| IStotal maximum | — | 236.04 | Highest individual value |

| IStotal high | 0.520 | 44.520 | Highest mean |

| ISfree high | Less than LOD | 4.520 | Highest mean |

| PCS (molecular weight 188) | |||

| PCStotal maximum | — | 105.078 | Highest individual value |

| PCStotal high | 2.977 | 43.078 | Highest mean |

| PCSfree high | 0.120 | 2.620 | Highest mean |

Highest individual value is the highest single value per patient ever reported; highest mean is the highest mean for a patient group ever reported. Current average values observed in an average dialysis population as reported in the most recent review of the European Uremic Toxin Group are 23.1 mg/L for IStotal and 20.9 mg/L for PCStotal.20 IS, indoxyl sulfate; LOD, limit of detection; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the review procedure and quality scoring.

Table 2.

Retained articles and their main characteristics

| First Author, Year, and Reference | Cell/Organ System | Toxin | Concentration (mg/L)/Dose | Albumin/Type Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) In vitro, albumin: normal | ||||

| Dou, 200426 | Endothelium | IS | 25–250 | 40 g/L |

| Odamaki, 200452 | Hepatocytes | IS | 50–100 | 40 g/L |

| Faure, 200628 | Endothelium | IS | 256 | 40 g/L |

| Yamamoto, 200651 | Smooth muscle cells | IS | 53–106 | 40 g/L |

| Dou, 200727 | Endothelium | IS | 125–250 | 40 g/L |

| Schepers, 200731 | Leukocytes | PCS | 121.0 | Whole blood |

| Itoh, 201229 | Endothelium | IS | 29.9–57.2 | 40 g/L |

| Chitalia, 201346 | Smooth muscle cells | IS | 25 | 40 g/L |

| Koppe, 201344 | Adipocytes, myotubes | PCS | 40 | 35 g/L |

| (2) In vitro, albumin: low, absent, or unspecified | ||||

| Tsujimoto, 201032 | Liver microsomes | IS | 6.36 | Absent |

| Lekawanvijit, 201035 | Cardiac fibroblasts/myocytes | IS | 0.02–63.6 | 5 g/L BSA/absent |

| Yu, 201133 | Endothelium | IS | 1.25–125 | Unspecified |

| Sun, 201334 | Proximal tubular cells | IS | 1; 5 | Absent |

| PCS | 1; 5 | |||

| Sun, 201236 | Proximal tubular cells | IS | 1–50 | Absent |

| PCS | 1–50 | |||

| Sun, 201239 | Proximal tubular cells | IS | 1; 5 | Unspecified |

| PCS | 1; 5 | |||

| Tsujimoto, 201248 | Intestinal cells (hepatic no effect) | IS | 4.24 | 0.8 g/L (10% FBS) |

| (3) Animala | ||||

| Adijang, 200840 | Aorta, kidney | IS | 23.1/200 mg/kg (30 wk) p.o. | DH rat |

| Ito, 201030b | Endothelium/leukocyte interaction | IS | 15.7/200 mg/kg q.d. (10 d) p.o. | Nx mouse |

| Adijang, 201041 | Aorta | IS | 15–20/200 mg/kg (32 wk) p.o. | DN, DH rat |

| Bolati, 201138b,c | Tubular cells | IS | 9.4–18.9/200 mg/kg (32 wk) p.o. | DH rat |

| Sun, 201236 | Tubular cells | IS | Unspecified/100 mg/kg q.d. (4 wk) i.p. | 1/2 Nx mouse |

| PCS | ||||

| Watanabe, 201345b | Renal tubular cells | PCS | 32.6/50 mg/kg q.d. (4 wk) i.p. | 5/6 Nx rat |

| Sun, 201239 | Proximal tubular cells | IS | 8.5 | 1/2 Nx mouse |

| PCS | 1.8 | |||

| 100 mg/kg q.d. (4 wk) i.p. | ||||

| Shimizu, 201237b,c | Proximal tubular cells | IS | 9.4–18.9/200 mg/kg (32 wk) p.o. | DN, DH rat |

| Shimizu, 201342b | Kidney (cortex) | IS | 9.4/200 mg/kg q.d. (32 wk) p.o. | DN rat |

| Shimizu, 201343b | Tubular cells | IS | 9.4/200 mg/kg (32 wk) p.o. | DN rat |

| Koppe, 201344 | Adipocytes, myocytes, various organs | PCS | 51/10 mg/kg b.i.d. (4 wk) i.p. | Normal RF mouse |

| Shimizu, 201347b,c | Tubular cells | IS | 9.4–18.9/200 mg/kg (32 wk) p.o. | DN, DH rat |

| Yisireyili, 201349 | Cardiac tissue | IS | 18.9/200 mg/kg q.d. (32 wk) p.o. | DN, DH rat |

| Bolati, 201350b | Tubular cells | IS | 9.4/200 mg/kg q.d. (32 wk) p.o. | DN, DH, rat |

IS, indoxyl sulfate; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate; BSA, bovine serum albumin; FBS, fetal bovine serum; wk, weeks; p.o., per os; q.d., once a day; i.p., intraperitoneal; b.i.d., twice per day; DH, Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive; Nx, nephrectomized; DN, Dahl salt-resistance normotensive; RF, renal function.

For animal experiments, we presumed that serum albumin was present at the same concentrations as usually in these animals; all solute concentrations were measured in serum, except for the study by Ito et al.30 (plasma), and steady state at the end of exposure on euthanasia of the animals, except for the study by Koppe et al.44 (peak after i.p. injection). Also, dose and administration route are mentioned; the Albumin/Type Model column contains both species and type of model.

In vitro part not appropriate.

If concentration is 9.4–18.9, it is 9.4 for Dahl wild-type rats and 18.9 for DH rats.

The number of retrievable studies increased considerably over the past years, suggesting a rising awareness about the topic. The distribution among countries points to a broad worldwide interest. The majority (n=20) was generated in Asia, especially Japan; however, seven studies in total were performed in Europe, the United States, or Australia.

The following cell and organ systems were investigated (n of each study is in parentheses) (Table 2): renal tubules (9),34,36–39,43,45,47,50 endothelium (6),26–30,33 leukocytes (2),30,31 whole vessels (2),40,41 whole kidney (2),40,42 cardiac cells (2),35,49 smooth muscle cells (2),46,51 hepatocytes (2),32,51 intestinal cells (1),48 and adipocytes (1).44 A few studies concentrated on more than one target system: one study was on both the whole vessel and kidney40 and one study was on leukocyte–endothelial interaction.30

Twenty-four studies concentrated on indoxyl sulfate,26–30,32–43,46–52 and six studies concentrated on p-cresyl sulfate.31,34,36,39,44,45 Three studies evaluated both compounds.34,36,39 Some studies also assessed alterations induced by other uremic toxins, but only two of those studies showed a significant effect for indole acetic acid,46,48 hippuric acid,48 and carboxy-methyl-propyl-furanpropionic acid.48

All studies evaluating indoxyl sulfate showed a negative (toxic) effect (Table 3), except the study by Odamaki et al.,52 which showed an increase of hepatocyte albumin production in the presence of indoxyl sulfate. Four studies on p-cresyl sulfate53–56 and one study on indoxyl sulfate55 showed no significant changes (data not shown).

Table 3.

Main relevant pathophysiologic changes per study

| Cell/Organ System | Toxin | Main Observed Effect |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Endothelium | ||

| Dou, 200426 | IS | Inhibition proliferation and repair |

| Faure, 200628 | IS | Increase endothelial microparticle release |

| Dou, 200727 | IS | Induction ROS, inhibition glutathione |

| Ito, 201030 | IS | Increase endothelial/leukocyte interaction (adhesion) |

| Yu, 201133 | IS | Inhibition proliferation; increase senescence; increase ROS and decrease NO production |

| Itoh, 201229 | IS | Induction ROS |

| (2) Smooth muscle cells | ||

| Yamamoto, 200651 | IS | Increase proliferation |

| Chitalia, 201346 | IS | Generation tissue factor (linked to clot formation), tissue factor breakdown retarded |

| (3) Leukocytes | ||

| Schepers, 200731 | PCS | Activation oxidative burst |

| Ito, 201030 | IS | Increase endothelial/leukocyte interaction (adhesion) |

| (4) Whole vessels | ||

| Adijang, 200840 | IS | Increase aortic calcification and stiffness, expression osteoblast markers, and OATs |

| Adijang, 201041 | IS | Induction cell senescence |

| (5) Cardiac cells | ||

| Lekawanvijit, 201035 | IS | Cardiomyocyte proliferation, cardiac fibrosis, inflammation |

| (6) Whole heart | ||

| Yisireyili, 201349 | IS | Increase cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, oxidative stress |

| (7) Renal tubular cells | ||

| Bolati, 201138 | IS | Increase epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| Sun, 201334 | IS, PCS | Enhanced expression cytokine and inflammatory genes |

| Sun, 201236 | IS, PCS | Activation RAAS and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis, nephrosclerosis |

| Shimizu, 201237 | IS | Increase expression MCP-1 |

| Sun, 201239 | IS, PCS | Increase Klotho gene methylation, renal fibrosis |

| Watanabe, 201245 | PCS | Increase renal tubular damage |

| Shimizu, 201343 | IS | Induction mediators for fibrosis (TGF-β1 and Smad3) |

| Shimizu, 201347 | IS | Induction generation adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) |

| Bolati, 201350 | IS | Increased oxidative stress |

| (8) Whole kidneys | ||

| Adijang, 200840 | IS | Increase fibrosis |

| Shimizu, 201342 | IS | Increase angiotensinogen expression |

| (9) Hepatocytes | ||

| Odamaki, 200452 | IS | Increase albumin production |

| Tsujimoto, 201032 | IS | Inhibition metabolic clearance losartan |

| (10) Intestinal cells | ||

| Tsujimoto, 201248 | IS | Inhibition pumps involved in clearance of pravastatin |

| (11) Adipocytes | ||

| Koppe, 201344 | PCS | Increase insulin resistance, decrease lipogenesis, increase lipolysis, ectopic lipid redistribution |

IS, indoxyl sulfate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, nitric oxide; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate; OATs, organic anion transporters; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; MCP-1, monocyte endothelial chemotactic protein-1; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

Of 14 animal studies, 10 studies were in rats,37,38,40–43,45,47,49,50 and four studies were in mice.30,36,39,44 Several of the rat studies were in the specific Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rat strain,37,38,40–43,47,49,50 although in some of these studies, an effect in the wild type was also observed.37,38,43,47,50 One study only evaluated Dahl wild-type rats and found a significant effect of indoxyl sulfate in that strain.42

Of the in vitro studies, eight studies applied an appropriate concentration of albumin, resulting in relevant free toxin concentrations,26–29,31,46,51,52 whereas in the remaining seven studies, a concentration compatible with the uremic free fraction was pursued.32–36,39,48

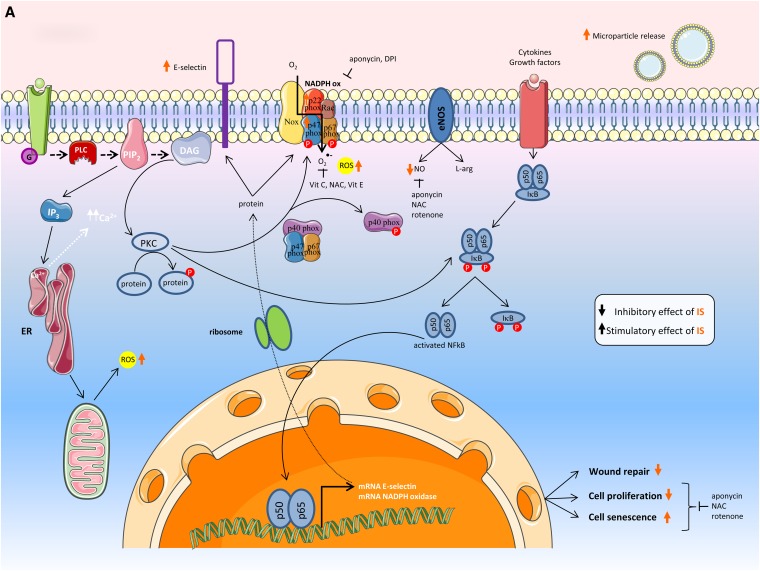

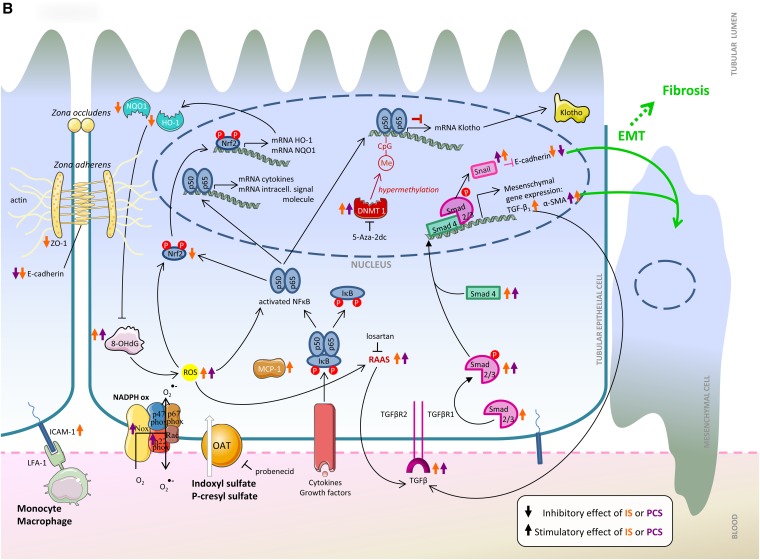

A large array of mediators, pathways, and messenger molecules contributed to the observed system effects (Table 4). Several were confirmed in more than one study of this series.27,30,34–36,38,40,43,45,48–50 Several of the observed effects were related to inflammation/free radical production27,30,34–36,44,45,48–50 and fibrosis.36,38–40,43,49 The mutual connections of these factors into global pathways for endothelial and proximal tubular cells are shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Most important affected pathophysiologic mechanisms

| Affected Mediators | Effect | Toxin | Confirmed in Two or More Studies | Related to Inflammation | Related to Fibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Smooth muscle actin36,38,40,49 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| Cytokine generation34,35 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| E-cadherin36,38 | ↓ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| Nuclear Factor (erythroid-derived 2) -like 249,50 | ↓ | IS | X | X | |

| Extracellular-regulated kinase 1/244 | ↑ | PCS | X | ||

| Fibronectin36 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | ||

| Heme oxygenase-149,50 | ↓ | IS | X | X | |

| Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-147 | ↑ | IS | X | ||

| Inflammatory genes34 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | ||

| Insulin receptor substrate-144 | ↓ | PCS | X | ||

| Klotho39 | ↓ | IS, PCS | X | ||

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase: MEK 1/2; p3835 | ↑ | IS | X | ||

| Multidrug resistance-associated protein-248 | ↓ | IS | |||

| NADPH oxidase27,30,45 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| Nuclear Factor-κB35 | ↑ | IS | X | ||

| Organic Anion Transporters40,48 | ↓ | IS | X | ||

| Osteoblast-specific proteins40 | ↑ | IS | X | ||

| Phosphoinositide 3-kinase44 | ↓ | PCS | X | ||

| Protein kinase B/Akt44 | ↓ | PCS | X | ||

| Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system36 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| E-selectin30 | ↑ | IS | X | ||

| Senescence proteins41a | ↑ | IS | |||

| Smad2/3 and Smad436,43 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| Snail36 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | ||

| Tissue factor46 | ↑ | IS | |||

| Transforming Growth Factor-β36,40,43,49 | ↑ | IS, PCS | X | X | |

| Zonula occludens-138 | ↓ | IS | X |

IS, indoxyl sulfate; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate.

Senescence proteins: senescence-associated β-galactosidase, 16INK4a, p21WAF1/CIP1, p53, and retinoblastoma protein.

Figure 2.

Effects as seen in the (A) endothelial cell and (B) renal tubular cell. The effects of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate are represented by orange and purple arrows, respectively. The transcellular membrane transport of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate by the organic anion transporters is represented by the thick white arrow. α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; 5-Aza-2dc, 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanine (DNA sequence); DAG, diacylglycerol; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; DPI, diphenylene iodonum chloride; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G, G protein-coupled receptor; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IKB, inhibitor of κB; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate; IS, indoxyl sulfate; L-arg, l-arginine; LFA-1, lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; Me, Methylgroup; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; NADPH ox, NADPH oxidase; NO, nitric oxide; NQO1, NADPH guinone oxidoreductase 1; Nrf, NF (erythroid-derived 2) -like; OAT, organic anion transporter; 8-OHdG, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine; p, protein; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; PKC, protein kinase C; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Vit C, vitamin C; Vit E, vitamin E; ZO-1, Zonula occludens protein 1.

With regards to quality, all retained studies together had a median score of 3.0 from a possible total of 5 points, indicating that approximately one half of the retained studies had a score of 3 points or above (Supplemental Material 1). Five studies reached a score of 5 of 5 points,35,36,39,44,45 and six studies obtained a score of 4 of 5 points.27,30,38,46,49,50 These 11 studies with a high quality score covered a broad array of pathophysiologic mechanisms mainly related to cardiovascular damage and progression of kidney disease: reactive oxygen species generation (3),27,45,50 endothelial dysfunction (2),27,30 epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (2),36,38 leukocyte–endothelial interaction (1),30 deterioration of cardiac cell functional capacity (1),35 Klotho expression (1),39 expression of tissue factor in vascular smooth muscle cells (1),46 and insulin resistance (1).44 The reasons for scoring 4 of 5 points instead of 5 of 5 points were lack of proof of concept by effect neutralization two times, the number of experiments was too low two times, lack of confirmation by an alternative approach one time, and absence of real-life conditions one time. There was no significant correlation between year of publication and quality score (data not shown).

Discussion

This study reviews the literature evidence up until June 30, 2013, for the biologic and/or toxic effects of two prototype protein-bound uremic toxins: indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate. In total, 27 studies from all over the world were retained, with the principal topics being endothelial and proximal tubular cell dysfunction, although insulin resistance, functional status of cardiac cells, leukocyte dysfunction, coagulation disturbances, and pharmacodynamics were also covered. A quality assessment identified 11 of 27 (41%) studies with a score of at least 4 points from a possible maximum of 5 points. The majority of the changes found affects mechanisms that are essential to the pathophysiology of the uremic syndrome and its subsequent deleterious impact on prognosis.

Endothelial dysfunction,26–30,33 smooth muscle cell lesions,46,51 coagulation disturbances,46 leukocyte activation,30,31 cross-talk of leukocytes and endothelium,30 cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy,35,49 and insulin resistance44 as well as whole-vessel alterations per se40,41 are all linked to cardiovascular damage and contribute to the increased propensity for mortality and cardiovascular events in CKD.57,58 Both indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate per se have repeatedly been related to cardiovascular mortality.10–19 Although strategies that more efficiently remove protein-bound solutes, such as frequent dialysis59 and online hemodiafiltration,60,61 in controlled studies are associated with improved outcomes,62,63 it remains difficult to interpret these data because of the presence of confounding factors that affect the outcomes on their own and a lack of selectivity of removal, because dialysis strategies are usually not restricted to protein-bound solutes alone.

Next to the above cardiovascular problems, the data linking these solutes to tubular cell damage,39,45 tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition,36,38 tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis,34,36,37,39,47,50 or whole-kidney damage40,42 are all are linked to the progression of CKD, another factor related to uremic morbidity and mortality.57 As a consequence, decrease in concentration of intestinally generated uremic retention solutes, like indole, by the intestinal sorbent AST-120 (Kremezin) has been accepted in mostly Asian countries as a strategy to restrain the progression of CKD. It is very likely that this sorbent affects the concentration of not only indoxyl sulfate but also, other protein-bound uremic toxins, one of which is p-cresyl sulfate.64 In at least two small-sized randomized controlled trials, AST-120 had a positive effect on progression of CKD.65,66 In a recent large randomized controlled trial in the United States and Europe, however, this positive effect could not be confirmed.67

Until now, biologic data were perceived as not consistent or convincing enough to recognize protein-bound toxins as the real culprits.25,68,69 The results of the current analysis applying systematic search methods linked to a quality assessment of the retrieved publications, however, yielded several high-quality papers applying, for the uremic setting, acceptable concentrations and state-of-the-art test methods. Therefore, our analysis offers, in our opinion, arguments that are solid enough to reconsider the reluctance to recognize the protein-bound solutes indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate as toxic.

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to apply to biologic studies a stringent strategy that had been defined in advance, in casu related to uremic retention, resulting in a systematized summary of their toxicity. Although we tried to follow current standards for the conduct of systematic reviews,70 there are methodological deviations. In contrast to evidence-based systematic reviews, in our case, only a limited number of search engines was used. Of note, for biologic studies, especially in the area of uremia, there is, to the best of our knowledge, not a large repository of data such as the one made available by the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) for clinical studies. Our approach may serve as a basis for future analyses of the same kind.

If we consider a quality score of 4 or 5 points of 5 points as the equivalent of a high evidence label, the results reported in the present article should provide a positive incentive to developing strategies to remove these protein-bound molecules better and more consistently than at present. Alternatives to the standard approaches that we now know to have a potentially beneficial impact are extended dialysis,71 prebiotics,72,73 probiotics72,73 and extracorporeal sorbents.74 Because our knowledge regarding this issue is extending, alternative options may arise in the nearby future. Anyway, the fact that dietary components and residual renal function seem to affect protein-bound solute concentration more than dialysis adequacy, as assessed by Kt/V,75 may suggest that alternative methods focusing on preserving kidney function or affecting intestinal toxin generation may be as important as extracorporeal removal.

The question could be raised as to how far toxic mechanisms and pathways overlap for both toxins. It is only possible if studies on the two compounds assess the same elements. To the best of our knowledge, for the time, such a parallel approach has only been used in renal tubular cells. Figure 2B confirms that, indeed, some mechanisms are overlapping.

This study has a few drawbacks. First, we focused only on two of the protein-bound solutes, whereas several other compounds in this group might have a biologic impact as well.3,5,6,76 We selected, however, the two molecules that have been most extensively evaluated. Some of the retained studies also show similar effects for other protein-bound solutes,46,48 suggesting that the yielded evidence could have been even more convincing if more compounds would have been taken into account. Second, we accepted concentrations up to the upper uremic range (Table 1),4,20,77,78 whereas in the average uremic patient, the concentration will be lower. However, a high concentration was applied essentially in vitro, where the concentration should be considered to compensate for short exposure to uremic toxins, in contrast to real life, where it is continuous, allowing solutes more time to reach the intracellular compartments where biologic activity is exerted. It is also of note that, in the in vivo animal studies, depending on the way of administration (intraperitoneally versus per os), the dose, and the type of model with regard to kidney function, fluctuating concentrations and different peak values might occur in the serum, which might, in turn, impact the interpretation of the observed biologic effect.

Third, our review data pointed overwhelmingly to a toxic effect of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate that may be skewed by submission bias. Investigators may be tempted not to finalize or publish studies showing no ill effect. Nevertheless, we retrieved five such studies by our analysis.52–56 Fourth, we should consider the possibility that we missed some studies in our analysis because of the approach followed, but more data would only increase the evidence delivered here.

However, our approach, based on rigid threshold levels, must also have excluded a number of interesting studies based on concentrations just above threshold77 and/or pathophysiologic key aspects highly relevant to the uremic syndrome, such as endothelial microparticle release,56 tissue factor activation,79 or metabolic capacity for glucuronidation.80

Because studies on toxicity in tubular cells suggest a relation to progression of kidney failure that is especially important in earlier stages of CKD, it can be argued that lower concentrations should be pursued in these experiments. However, even in dialysis patients, restraining progression may have a substantial clinical impact, because residual renal function is definitely inversely related to mortality.81 In addition, in most of studies on tubular toxicity that were retrieved,34,36–39,42,43,45,47,50 concentrations were in the same range as those concentrations found in patients with CKD stages 3–5 not on dialysis13,82 (i.e., lower than in dialysis patients).

In conclusion, a systematic retrieval approach searching for experimental studies evaluating the biologic (toxic) impact of the uremic solutes indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate and taking into account precise criteria for concentrations that considered protein binding yielded 27 publications that conformed with the inclusion criteria.

Eleven of these studies obtained a high-quality score, indicating a substantial scientific impact. Most frequently, missing quality factors were insufficient number of experiments, lack of a dose–response analysis, and especially, absence of data showing the neutralization of the effect found by counteragents of the presumed mechanism. Future studies should comply with these conditions to be considered of high quality. The retrieved studies covered a broad array of effects, most of them related to clinically highly relevant aspects, such as cardiovascular disease or progression of CKD. These data, if matched to observational outcome studies,6,10–19 are the best evidence that we can obtain right now for the clinical impact of protein-bound solutes. This knowledge may be supportive of the development of strategies to lower the concentration of these solutes in the body.

Concise Methods

The study was limited to indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, the two protein-bound uremic toxins that have been most extensively evaluated until now. A literature search using Pubmed through Reference Manager was undertaken with the following terms: p-cresyl sulfate or p-cresylsulfate, or indoxylsulfate or indoxyl sulfate. This search was completed with additional references emanating from the originally retrieved publications. The search contained all obtained references with June 30, 2013, as closing date (Figure 1).

We only included primary studies assessing the biologic effect of indoxyl sulfate and/or p-cresyl sulfate in vitro or in animals where an acceptable free concentration was present. For this reason, analytical studies, clinical concentration or outcome studies, and studies on the origin and generation of the compounds of interest, medical interventions to decrease their concentration, and removal by dialysis or other strategies were all excluded. Also, studies not specifying the pursued solute concentrations or unclear on the applied methods, making reproduction of the experiments difficult, were rejected as well as reviews, abstracts, and studies referring to conditions other than CKD, including AKI.

Only studies conforming to the preset target concentrations, defined as values not exceeding the highest levels obtained in uremia (reported in Table 1), were included.4,20,77,78 Additional conditions for accepting a study were as follows: in vitro studies with use of medium containing concentrations of albumin corresponding to real-life in vivo conditions or animal studies with injection or oral administration of the molecules of interest or their precursors and the appropriate concentration of toxin and serum albumin. In the absence of albumin in vitro, the use of solute concentrations had to be in accordance with reported free toxin concentrations, which is also detailed in Table 2.

Based on this approach, two investigators independently selected the studies and extracted all data, with discrepancies resolved by a third investigator (Figure 1).

The studies were then checked for their content using a data extraction list conceived as reported in Supplemental Material 1, with specific attention to the experimental setting, the assessed problem, the molecule of interest, the applied concentrations, the presence (or absence) of appropriate concentrations of albumin, the involved pathways, and the successful application of neutralizing interventions.

From our analysis, it became clear that the quality of the retrieved publications was not always the same. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no checklists available for evaluating quality or reliability of primary studies of biologic effects, the primary target of our search. Thus, we developed a quality score (Supplemental Material 2) that was given to each study based on the number of experiments (1 point if six or more experiments); confirmation of the obtained results by an alternative approach (same parameter, different methods, same pathway, different parameters; 1 point); proof of neutralization of the basic identified mechanism by the appropriate antibodies, counteractive agents, or other interventions (1 point); use of a real-life model (1 point; here, we excluded studies in specific genetic animal strains instead of wild type, especially because results between these two groups in our search were not always conformed20,40,42,49; also, specific cell types that are not necessarily representative of real-life conditions were excluded [e.g., human umbilical vein endothelial cells], because the phenotype of venous endothelium does not always match that of the arterial cell, which is where uremic vascular damage and atherosclerosis essentially take place83–85); and finally; performance of dose–response experiments but only if the other conditions were appropriate (in the presence of albumin or in the free concentration range; 1 point). Thus, a maximum quality score of 5 points could be obtained.

These quality scores were attributed independently by two of the authors and matched and double-checked by a third author in case of disagreement.

Because there are substantial ethical and practical obstacles to performing dose–response experiments for in vivo animal studies, 1 extra point was added to all publications containing animal studies as long as the same publication did not include in vitro dose–response studies as well.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Caroline Vinck for linguistic correction of this publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013101062/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Uremia. N Engl J Med 357: 1316–1325, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanholder R, Baurmeister U, Brunet P, Cohen G, Glorieux G, Jankowski J, European Uremic Toxin Work Group : A bench to bedside view of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 863–870, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanholder R, Van Laecke S, Glorieux G: What is new in uremic toxicity? Pediatr Nephrol 23: 1211–1221, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanholder R, De Smet R, Glorieux G, Argilés A, Baurmeister U, Brunet P, Clark W, Cohen G, De Deyn PP, Deppisch R, Descamps-Latscha B, Henle T, Jörres A, Lemke HD, Massy ZA, Passlick-Deetjen J, Rodriguez M, Stegmayr B, Stenvinkel P, Tetta C, Wanner C, Zidek W, European Uremic Toxin Work Group (EUTox) : Review on uremic toxins: Classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int 63: 1934–1943, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanholder R, De Smet R, Lameire N: Protein-bound uremic solutes: The forgotten toxins. Kidney Int Suppl 78[Suppl 78]: S266–S270, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanholder R, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Neirynck N, Glorieux G: An update on protein-bound uremic retention solutes. J Ren Nutr 22: 90–94, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glorieux G, Vanholder R: New uremic toxins - which solutes should be removed? Contrib Nephrol 168: 117–128, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neirynck N, Glorieux G, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Dhondt A, Vanholder R: Review of protein-bound toxins, possibility for blood purification therapy. Blood Purif 35[Suppl 1]: 45–50, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neirynck N, Vanholder R, Schepers E, Eloot S, Pletinck A, Glorieux G: An update on uremic toxins. Int Urol Nephrol 45: 139–150, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijers BK, Claes K, Bammens B, de Loor H, Viaene L, Verbeke K, Kuypers D, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P: p-Cresol and cardiovascular risk in mild-to-moderate kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1182–1189, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Smet R, Van Kaer J, Van Vlem B, De Cubber A, Brunet P, Lameire N, Vanholder R: Toxicity of free p-cresol: A prospective and cross-sectional analysis. Clin Chem 49: 470–478, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijers BK, Bammens B, De Moor B, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P: Free p-cresol is associated with cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 73: 1174–1180, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liabeuf S, Barreto DV, Barreto FC, Meert N, Glorieux G, Schepers E, Temmar M, Choukroun G, Vanholder R, Massy ZA, European Uraemic Toxin Work Group (EUTox) : Free p-cresylsulphate is a predictor of mortality in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1183–1191, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CJ, Wu CJ, Pan CF, Chen YC, Sun FJ, Chen HH: Serum protein-bound uraemic toxins and clinical outcomes in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3693–3700, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CP, Lu LF, Yu TH, Hung WC, Chiu CA, Chung FM, Yeh LR, Chen HJ, Lee YJ, Houng JY: Serum levels of total p-cresylsulphate are associated with angiographic coronary atherosclerosis severity in stable angina patients with early stage of renal failure. Atherosclerosis 211: 579–583, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CP, Lu LF, Yu TH, Hung WC, Chiu CA, Chung FM, Hsu CC, Lu YC, Lee YJ, Houng JY: Associations among chronic kidney disease, high total p-cresylsulfate and major adverse cardiac events. J Nephrol 26: 111–118, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu IW, Hsu KH, Hsu HJ, Lee CC, Sun CY, Tsai CJ, Wu MS: Serum free p-cresyl sulfate levels predict cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in elderly hemodialysis patients—a prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1169–1175, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu IW, Hsu KH, Lee CC, Sun CY, Hsu HJ, Tsai CJ, Tzen CY, Wang YC, Lin CY, Wu MS: p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 938–947, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu CA, Lu LF, Yu TH, Hung WC, Chung FM, Tsai IT, Yang CY, Hsu CC, Lu YC, Wang CP, Lee YJ: Increased levels of total P-Cresylsulphate and indoxyl sulphate are associated with coronary artery disease in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Rev Diabet Stud 7: 275–284, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duranton F, Cohen G, De Smet R, Rodriguez M, Jankowski J, Vanholder R, Argiles A, European Uremic Toxin Work Group : Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1258–1270, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammarlund-Udenaes M: Active-site concentrations of chemicals - are they a better predictor of effect than plasma/organ/tissue concentrations? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 106: 215–220, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joerger M, Huitema AD, Boogerd W, van der Sande JJ, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH: Interactions of serum albumin, valproic acid and carbamazepine with the pharmacokinetics of phenytoin in cancer patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 99: 133–140, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith BS, Yogaratnam D, Levasseur-Franklin KE, Forni A, Fong J: Introduction to drug pharmacokinetics in the critically ill patient. Chest 141: 1327–1336, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viaene L, Annaert P, de Loor H, Poesen R, Evenepoel P, Meijers B: Albumin is the main plasma binding protein for indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate. Biopharm Drug Dispos 34: 165–175, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirich T, Meyer TW: Indoxyl sulfate: Long suspected but not yet proven guilty. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 3–4, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dou L, Bertrand E, Cerini C, Faure V, Sampol J, Vanholder R, Berland Y, Brunet P: The uremic solutes p-cresol and indoxyl sulfate inhibit endothelial proliferation and wound repair. Kidney Int 65: 442–451, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dou L, Jourde-Chiche N, Faure V, Cerini C, Berland Y, Dignat-George F, Brunet P: The uremic solute indoxyl sulfate induces oxidative stress in endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost 5: 1302–1308, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faure V, Dou L, Sabatier F, Cerini C, Sampol J, Berland Y, Brunet P, Dignat-George F: Elevation of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with chronic renal failure. J Thromb Haemost 4: 566–573, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itoh Y, Ezawa A, Kikuchi K, Tsuruta Y, Niwa T: Protein-bound uremic toxins in hemodialysis patients measured by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and their effects on endothelial ROS production. Anal Bioanal Chem 403: 1841–1850, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito S, Osaka M, Higuchi Y, Nishijima F, Ishii H, Yoshida M: Indoxyl sulfate induces leukocyte-endothelial interactions through up-regulation of E-selectin. J Biol Chem 285: 38869–38875, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schepers E, Meert N, Glorieux G, Goeman J, Van der Eycken J, Vanholder R: P-cresylsulphate, the main in vivo metabolite of p-cresol, activates leucocyte free radical production. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 592–596, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujimoto M, Higuchi K, Shima D, Yokota H, Furukubo T, Izumi S, Yamakawa T, Otagiri M, Hirata S, Takara K, Nishiguchi K: Inhibitory effects of uraemic toxins 3-indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol on losartan metabolism in vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol 62: 133–138, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu M, Kim YJ, Kang DH: Indoxyl sulfate-induced endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease via an induction of oxidative stress. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 30–39, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun CY, Hsu HH, Wu MS: p-Cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate induce similar cellular inflammatory gene expressions in cultured proximal renal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 70–78, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lekawanvijit S, Adrahtas A, Kelly DJ, Kompa AR, Wang BH, Krum H: Does indoxyl sulfate, a uraemic toxin, have direct effects on cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes? Eur Heart J 31: 1771–1779, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun CY, Chang SC, Wu MS: Uremic toxins induce kidney fibrosis by activating intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE 7: e34026, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu H, Bolati D, Higashiyama Y, Nishijima F, Shimizu K, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate upregulates renal expression of MCP-1 via production of ROS and activation of NF-κB, p53, ERK, and JNK in proximal tubular cells. Life Sci 90: 525–530, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolati D, Shimizu H, Higashiyama Y, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in rat kidneys and human proximal tubular cells. Am J Nephrol 34: 318–323, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun CY, Chang SC, Wu MS: Suppression of Klotho expression by protein-bound uremic toxins is associated with increased DNA methyltransferase expression and DNA hypermethylation. Kidney Int 81: 640–650, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adijiang A, Goto S, Uramoto S, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulphate promotes aortic calcification with expression of osteoblast-specific proteins in hypertensive rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1892–1901, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adijiang A, Higuchi Y, Nishijima F, Shimizu H, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin, promotes cell senescence in aorta of hypertensive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 399: 637–641, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu H, Saito S, Higashiyama Y, Nishijima F, Niwa T: CREB, NF-κB, and NADPH oxidase coordinately upregulate indoxyl sulfate-induced angiotensinogen expression in proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C685–C692, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu H, Yisireyili M, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate enhances p53-TGF-β1-Smad3 pathway in proximal tubular cells. Am J Nephrol 37: 97–103, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koppe L, Pillon NJ, Vella RE, Croze ML, Pelletier CC, Chambert S, Massy Z, Glorieux G, Vanholder R, Dugenet Y, Soula HA, Fouque D, Soulage CO: p-Cresyl sulfate promotes insulin resistance associated with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 88–99, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe H, Miyamoto Y, Honda D, Tanaka H, Wu Q, Endo M, Noguchi T, Kadowaki D, Ishima Y, Kotani S, Nakajima M, Kataoka K, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Tanaka M, Fukagawa M, Otagiri M, Maruyama T: p-Cresyl sulfate causes renal tubular cell damage by inducing oxidative stress by activation of NADPH oxidase. Kidney Int 83: 582–592, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chitalia VC, Shivanna S, Martorell J, Balcells M, Bosch I, Kolandaivelu K, Edelman ER: Uremic serum and solutes increase post-vascular interventional thrombotic risk through altered stability of smooth muscle cell tissue factor. Circulation 127: 365–376, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu H, Yisireyili M, Higashiyama Y, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate upregulates renal expression of ICAM-1 via production of ROS and activation of NF-κB and p53 in proximal tubular cells. Life Sci 92: 143–148, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsujimoto M, Hatozaki D, Shima D, Yokota H, Furukubo T, Izumi S, Yamakawa T, Minegaki T, Nishiguchi K: Influence of serum in hemodialysis patients on the expression of intestinal and hepatic transporters for the excretion of pravastatin. Ther Apher Dial 16: 580–587, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yisireyili M, Shimizu H, Saito S, Enomoto A, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate promotes cardiac fibrosis with enhanced oxidative stress in hypertensive rats. Life Sci 92: 1180–1185, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolati D, Shimizu H, Yisireyili M, Nishijima F, Niwa T: Indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin, downregulates renal expression of Nrf2 through activation of NF-κB. BMC Nephrol 14: 56, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto H, Tsuruoka S, Ioka T, Ando H, Ito C, Akimoto T, Fujimura A, Asano Y, Kusano E: Indoxyl sulfate stimulates proliferation of rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int 69: 1780–1785, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Odamaki M, Kato A, Kumagai H, Hishida A: Counter-regulatory effects of procalcitonin and indoxyl sulphate on net albumin secretion by cultured rat hepatocytes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 797–804, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanholder R, De Smet R, Waterloos MA, Van Landschoot N, Vogeleere P, Hoste E, Ringoir S: Mechanisms of uremic inhibition of phagocyte reactive species production: Characterization of the role of p-cresol. Kidney Int 47: 510–517, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu JZ, Zhang J, Yang K, Du R, Jing YJ, Lu L, Zhang RY: P-cresol, but not p-cresylsulphate, disrupts endothelial progenitor cell function in vitro. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4323–4330, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viaene L, Evenepoel P, Meijers B, Vanderschueren D, Overbergh L, Mathieu C: Uremia suppresses immune signal-induced CYP27B1 expression in human monocytes. Am J Nephrol 36: 497–508, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meijers BK, Van Kerckhoven S, Verbeke K, Dehaen W, Vanrenterghem Y, Hoylaerts MF, Evenepoel P: The uremic retention solute p-cresyl sulfate and markers of endothelial damage. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 891–901, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanholder R, Massy Z, Argiles A, Spasovski G, Verbeke F, Lameire N, European Uremic Toxin Work Group : Chronic kidney disease as cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1048–1056, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT, Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fagugli RM, De Smet R, Buoncristiani U, Lameire N, Vanholder R: Behavior of non-protein-bound and protein-bound uremic solutes during daily hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 339–347, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meert N, Eloot S, Schepers E, Lemke HD, Dhondt A, Glorieux G, Van Landschoot M, Waterloos MA, Vanholder R: Comparison of removal capacity of two consecutive generations of high-flux dialysers during different treatment modalities. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 2624–2630, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meert N, Eloot S, Waterloos MA, Van Landschoot M, Dhondt A, Glorieux G, Ledebo I, Vanholder R: Effective removal of protein-bound uraemic solutes by different convective strategies: A prospective trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 562–570, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chertow GM, Levin NW, Beck GJ, Depner TA, Eggers PW, Gassman JJ, Gorodetskaya I, Greene T, James S, Larive B, Lindsay RM, Mehta RL, Miller B, Ornt DB, Rajagopalan S, Rastogi A, Rocco MV, Schiller B, Sergeyeva O, Schulman G, Ting GO, Unruh ML, Star RA, Kliger AS, FHN Trial Group : In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med 363: 2287–2300, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maduell F, Moreso F, Pons M, Ramos R, Mora-Macià J, Carreras J, Soler J, Torres F, Campistol JM, Martinez-Castelao A, ESHOL Study Group : High-efficiency postdilution online hemodiafiltration reduces all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 487–497, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kikuchi K, Itoh Y, Tateoka R, Ezawa A, Murakami K, Niwa T: Metabolomic search for uremic toxins as indicators of the effect of an oral sorbent AST-120 by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 878: 2997–3002, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akizawa T, Asano Y, Morita S, Wakita T, Onishi Y, Fukuhara S, Gejyo F, Matsuo S, Yorioka N, Kurokawa K, CAP-KD Study Group : Effect of a carbonaceous oral adsorbent on the progression of CKD: A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 459–467, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Konishi K, Nakano S, Tsuda S, Nakagawa A, Kigoshi T, Koya D: AST-120 (Kremezin) initiated in early stage chronic kidney disease stunts the progression of renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 81: 310–315, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.2013. Available at: http://www.medpagetoday.com/MeetingCoverage/ASN/35737 Accessed April 18, 2014

- 68.Winchester JF, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: p-Cresol sulfate: Further understanding of its cardiovascular disease potential in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 792–794, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dobre M, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH: Searching for uremic toxins. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 322–327, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, editors: Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, D.C., The National Academies Press, 2011. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13059 Accessed April 18, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sirich TL, Luo FJ, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW: Selectively increasing the clearance of protein-bound uremic solutes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1574–1579, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Evenepoel P, Meijers BK, Bammens BR, Verbeke K: Uremic toxins originating from colonic microbial metabolism. Kidney Int Suppl 114: S12–S19, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schepers E, Glorieux G, Vanholder R: The gut: The forgotten organ in uremia? Blood Purif 29: 130–136, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meijers BK, Weber V, Bammens B, Dehaen W, Verbeke K, Falkenhagen D, Evenepoel P: Removal of the uremic retention solute p-cresol using fractionated plasma separation and adsorption. Artif Organs 32: 214–219, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eloot S, Van Biesen W, Glorieux G, Neirynck N, Dhondt A, Vanholder R: Does the adequacy parameter Kt/V(urea) reflect uremic toxin concentrations in hemodialysis patients? PLoS ONE 8: e76838, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vanholder R, Glorieux G, De Smet R, Lameire N, European Uremic Toxin Work Group : New insights in uremic toxins. Kidney Int Suppl 84: S6–S10, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meert N, Schepers E, Glorieux G, Van Landschoot M, Goeman JL, Waterloos MA, Dhondt A, Van der Eycken J, Vanholder R: Novel method for simultaneous determination of p-cresylsulphate and p-cresylglucuronide: Clinical data and pathophysiological implications. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2388–2396, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vanholder R, Bammens B, de Loor H, Glorieux G, Meijers B, Schepers E, Massy Z, Evenepoel P: Warning: The unfortunate end of p-cresol as a uraemic toxin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1464–1467, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gondouin B, Cerini C, Dou L, Sallee M, Duval-Sabatier A, Pletinck A, Calaf R, Lacroix R, Jourde-Chiche N, Poitevin S, Arnaud L, Vanholder R, Brunet P, Dignat-George F, Burtey S: Indolic uremic solutes increase tissue factor production in endothelial cells by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway. Kidney Int 84: 733–744, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mutsaers HA, Wilmer MJ, Reijnders D, Jansen J, van den Broek PH, Forkink M, Schepers E, Glorieux G, Vanholder R, van den Heuvel LP, Hoenderop JG, Masereeuw R: Uremic toxins inhibit renal metabolic capacity through interference with glucuronidation and mitochondrial respiration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832: 142–150, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van der Wal WM, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Korevaar JC, Geskus RB, Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis Study Group (NECOSAD) : Full loss of residual renal function causes higher mortality in dialysis patients; findings from a marginal structural model. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 2978–2983, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, Meert N, Glorieux G, Temmar M, Choukroun G, Vanholder R, Massy ZA, European Uremic Toxin Work Group (EUTox) : Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1551–1558, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Szasz T, Thakali K, Fink GD, Watts SW: A comparison of arteries and veins in oxidative stress: Producers, destroyers, function, and disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 232: 27–37, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mateo T, Naim Abu Nabah Y, Losada M, Estellés R, Company C, Bedrina B, Cerdá-Nicolás JM, Poole S, Jose PJ, Cortijo J, Morcillo EJ, Sanz MJ: A critical role for TNFalpha in the selective attachment of mononuclear leukocytes to angiotensin-II-stimulated arterioles. Blood 110: 1895–1902, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Johnson AR: Human pulmonary endothelial cells in culture. Activities of cells from arteries and cells from veins. J Clin Invest 65: 841–850, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.