Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) entry into target cell is initiated by the ionic interactions between positively charged viral envelop glycoproteins and a negatively charged cell surface heparan sulfate (HS). This first step involves the induction of HS-rich filopodia-like structures on the cell surface that facilitate viral transport during cell entry. Targeting this initial first step in HSV-1 pathogenesis, we generated different zinc oxide (ZnO) micro-nano structures (MNSs) that were capped with multiple nanoscopic spikes mimicking cell induced filopodia. These MNSs were predicted to target the virus to compete for its binding to cellular HS through their partially negatively charged oxygen vacancies on their nanoscopic spikes, to affect viral entry and subsequent spread. Our results demonstrate that the partially negatively charged ZnO-MNSs efficiently trap the virions via a novel virostatic mechanism rendering them unable to enter into human corneal fibroblasts-a natural target cell for HSV-1 infection. The anti-HSV-1 activity of ZnO MNSs was drastically enhanced after creating additional oxygen vacancies under UV-light illumination. Our results provide a novel insight into the significance of ZnO MNSs as the potent HSV-1 inhibitor and rationalize their development as a novel topical agent for the prevention of HSV-1 infection.

Keywords: Zinc oxide structures, herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1), virus-cell interaction

1. Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) infections are extremely widespread in the human population. The virus causes a broad range of diseases ranging from labial herpes, ocular keratitis, genital disease and encephalitis (Whitley and Kimberlin, 1997; Whitley et al., 1998; Corey and Spear, 1988). The herpetic infection is a major cause of morbidity especially in immunocompromised patients. Following initial infection in epithelial cells, the HSV establishes latency in the host sensory nerve ganglia (Akhtar and Shukla, 2009; Hill et al., 2008). The virus emerges sporadically from latency and causes lesions on mucosal epithelium, skin, and the cornea, among other locations. Prolonged or multiple recurrent episodes of corneal infections can result in vision impairment or blindness, due to the development of herpetic stromal keratitis (HSK) (Kaye et al., 2000). HSK accounts for 20–48% of all recurrent ocular HSV infections leading to significant vision loss (Liesegang, 2001). HSV infection may also lead to other diseases including retinitis, meningitis, and encephalitis (Corey and Spear, 1988).

HSV entry into host cells initiates the primary infection. It is a multi-step process that starts with specific interaction of viral envelope glycoproteins and host cell surface receptors (Spear et al., 2000). HSV-1 uses envelope glycoproteins B and C (gB and gC, respectively) to mediate its initial attachment to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) (WuDunn and Spear, 1989). The initial binding of HSV to HSPG likely precedes a conformational change that brings viral glycoprotein D (gD) to the binding domain of host cell surface gD receptors: HVEM, nectin-1 or 3-OS HS (Spear et al., 2000; Shukla and Spear, 2001). Binding of gD to its receptor is essential for viral penetration, which ultimately results in deposition of viral DNA for replication in the nucleus.

The initial discovery that HSV-1 envelope glycoprotein gB binds to HS receptor either on cell induced filopodia (Oh et al., 2010) or cell membrane and subsequently to a fusion receptor during HSV-1 entry stimulated research to develop particular molecules which can interfere multiple steps during cell entry to prevent the viral infection. In this regard, cell-associated HS and modified form of HS (3-OS HS) represents an attractive target because HS/3-OS HS is endowed with its remarkable ability to bind numerous viral proteins including multiple HSV-1 glycoproteins (Shukla and Spear, 2001; O’Donnell and Shukla, 2008; O’Donnell and Shukla, 2009). The significance of HS in viral diseases is also evident from recent reports that polysulfated compounds, HS-binding peptides and HS-mimetic are very effective in blocking viral infections (Rusnati and Urbinati, 2009; Nyberg et al., 2004; Raghuraman et al., 2005; Raghuraman 2007, Tiwari et al., 2009; Tiwari et al., 2011). Realizing the significance of HS in HSV-1 infectivity, we designed multifunctional zinc oxide (ZnO) MNSs capped with nanoscopic filopodia-like spikes which mimic the cellular filopodial structure with a partial negative charge due to oxygen vacancies present on them. We hypothesized that negatively charged ZnO nanospike (NSs) will compete for viral binding to cellular HS. Using multiple molecular and biochemical based assays we demonstrated that ZnO MNSs at non-toxic concentrations significantly trapped the HSV-1 affecting viral binding to cell during entry and spread. The ZnO MNSs capped with nanoscopic filopodia-like spikes may serve as useful topical agents for the prevention of HSV-1 infections.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation and characterization of spikes containing ZnO micro-nano structures

The snowflake type free standing complex network of interconnected zinc oxide micro- and nano structures (thickness in the range of 100 to 500 nm and length in the range of 1 to 5 μm) which consists of hexagonal nanorods, tetrapods, nanocombs and nano-sea urchin like structures, were synthesized by a simple flame transport synthesis approach using a sacrificial polymer (polyvinyl butyrol) as the local host. Commercial Zn powder (particle diameter ~ 3 to 5 μm) was purchased from Goodfellows (UK) and polyvinyl butyrol (PVB) powder was supplied by Kuraray Europe GmbH. The Zn and PVB powders were mixed in particular ratio with the help of Ethanol and then heated in a simple furnace at 900 °C for 1 hour. The process for micro-nano structure formation was used as previously described (S. Kaps, R. Adelung, C. Wolpert, T. Preusse, M. Claus, Y. K. Mishra, Elastisches Material mit einem auf Partikelebene durch Nanobrücken zwischen Partikeln überbrückten, Deutsches Patentamt, 2.03.2010, DE 10 2010 012 385.4.). The microstructural evolution of different micro-nano structures inside snowflake type free standing powdery material was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Philips XL-30 microscope equipped with LaB6 filament and energy dispersive X-ray diffraction analysis (EDAX) detector. SEM images of different structures were recorded at 6 kV electron beam acceleration voltage with 20 μA, beam current at University of Kiel. A large quantity of snowflake type ZnO micro-nanostructured powder was synthesized under identical conditions which were used for different biomedical tests as described in the next sections.

2.2. Cytotoxic assay

The cytotoxicity of the ZnO MNSs after 24 h of treatment was determined by MTT assay (Mosmann, 1983; Röhl and Sievers, 2005) and protein measurement (Lowry et al., 1951). After two days in culture, when confluence was reached, fibroblasts (NHDF) were treated with ZnO nanoparticles. ZnO nanoparticles were either first irradiated with UV light at 254 nm for one hour distributed in a thin layer in a plastic petri dish or they were directly brought into suspension with culture medium at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. This stock solution was used to prepare the samples. For the treatment culture medium was completely removed and cells were treated with 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 5 mg/ml ZnO nanoparticles (−/+ UV) for 24 h. Cells were washed carefully one time with the culture medium before using MTT assay or three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before the protein measurement. Using the MTT assay the portion of viable cells in treated cultures was estimated on the basis of the formation of formazan by viable cells. Formazan and protein suspensions were transferred to new plates before calorimetrical measurements performed at 570 nm for the MTT test and at 630 nm for the protein measurement (universal microplate reader ELx800UV, Bio-Tek Instruments Inc.).

2.3. Cells, plasmids and viruses

HeLa and cultured human corneal fibroblasts (CF) cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Corp.) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), while wild-type CHO-K1 cells expressing gD receptors (nectin-1 and 3-OST-3) were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium (Gibco/BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, and penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco/BRL). Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) (PromoCell, C-12300) were cultured in Quantum 333 medium (PAA, U15-813) supplemented with 1 % (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin. Subcultured fibroblasts (maximum until passage 9) were seeded into 96-well microtiter plates at a seeding density of 100 000 cells/cm2 in 310 μl/cm2 medium. Cells were kept at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. The β-galactosidase expressing recombinant HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 (Shukla et al., 1999), clinically-relevant isolates of HSV (F, G, and MP) and GFP-expressing HSV-1 (K26GFP) were provided by P.G. Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago) and P. Desai (Johns Hopkins University) (Desai and Person, 1998). The plasmids expressing nectin-1 (pBG38) was kindly provided by Dr. Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago).

2.4. Viral entry assay

Viral entry assays were based on quantitation of β-galactosidase expressed from the viral genome in which β-galactosidase expression is inducible by HSV infection. Cells were transiently transfected in 6-well tissue culture dishes with plasmids expressing HSV-1 entry receptors (necitn-1 expression plasmids) using Lipofectamine 2000 at 1.5 μg DNA per well in 1 ml. At 24 hr post-transfection, cells were re-plated in 96-well tissue culture dishes (2 × 10 4 cells per well) at least 16 hr prior to infection. Cells were washed and exposed to serially diluted pre-incubated virus with ZnO MNSs or 1 × PBS at two fold dilutions in 50 μl of PBS containing 0.1% glucose and 1% heat inactivated CS (PBS-G-CS) for 6 hr at 37 °C before solubilization in 100 μl of PBS containing 0.5% NP-40 and the β-galactosidase substrate, o-nitro-phenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG; ImmunoPure, PIERCE, Rockford, IL, 3 mg/ml). The enzymatic activity was monitored at 410 nm by spectrophotometry (BioTek Instruments Inc. EL×808 absorbance microplate reader, VT, USA). In addition, viral entry assay was also performed in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. The β-galactosidase expressing HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 reporter virus at 2 × 108 PFU was pre-incubated with mock (1 × PBS) or 100 μg/ml MNSs for 2 hours before infecting zebrafish embryos (three embryos per well in a 96 well plate) for 12 hr. HSV-1 entry in both the groups of embryos were measured by ONPG assay described above.

2.5. Mixing of fluorescent-labeled ZnO micro-nano structures with GFP-tagged HSV-1

The free standing ZnO MNSs (seaurchins and tatrapod shaped particles containing long filapodia type of spikes) from snowflake type powder were distributed in a thin layer in a plastic petri dish followed by irradiation with UV light at 254 nm for 30 min at room temperature. In this experiment ZnO-MNSs were stained with 10 nm rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) followed by mixing with GFP-tagged HSV-1 or with 1× PBS. Images of fluorescent labeled ZnO-MPs (either pre-treated with UV+ or untreated UV−) mixed with GFP-tagged HSV-1 were acquired using a confocal microscope (Nikon D-Eclipse-C1) with the software EZ-C1.

2.6. Virus-free cell-to-cell fusion assay

In this experiment, the CHO-K1 cells (grown in F-12 Ham, Invitrogen) designated as “effector” cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing four HSV-1(KOS) glycoproteins, pPEP98 (gB), pPEP99 (gD), pPEP100 (gH) and pPEP101 (gL), along with the plasmid pT7EMCLuc that expresses firefly luciferase gene under the T7 promoter (Tiwari et al., 2004). Wild-type CHO-K1 cells express cell surface HS but lack functional gD receptors, therefore transiently transfected with HSV-1 entry receptors. Wild type CHO-K1 cultured cells expressing HSV-1 entry receptor nectin-1 considered as “target cells” were co-transfected with pCAGT7 that expresses T7 RNA polymerase using chicken actin promoter and CMV enhancer. The untreated effectors cells expressing pT7EMCLuc and HSV-1 essential glycoproteins and the target cells expressing gD receptors transfected with T7 RNA polymerase were used as the positive control. While the ZnO MNSs treated effectors cells were used for the test. For fusion, at 18 hr post transfection, the target and the effector cells were mixed together (1:1 ratio) and co-cultivated in a 24 well-dishes. The activation of the reporter luciferase gene as a measure of cell fusion was examined using reporter lysis Assay (Promega) at 24 hr post mixing.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of ZnO micro nano structures (MNSs) and cell toxicity

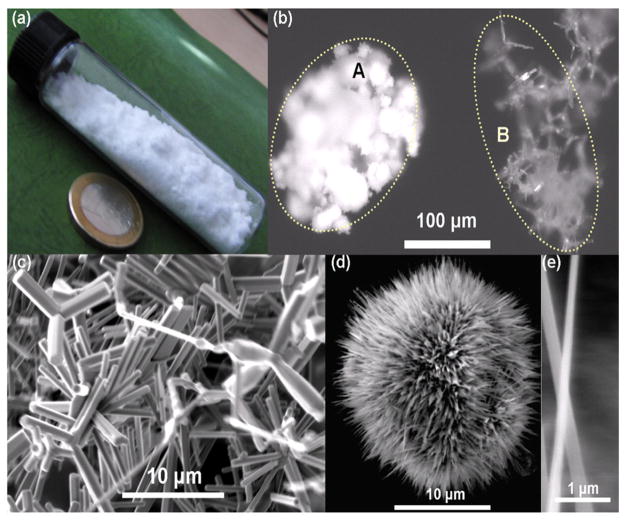

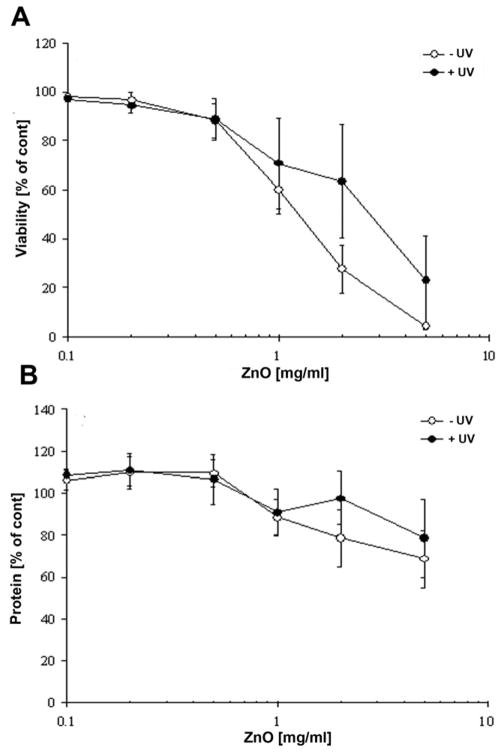

The large quantities (several 100 grams) of snowflake type ZnO micro nano structures (tetrapods, interconnected hexagonal rods, seaurchins capped with nanoscopic filopodia) were synthesized by flame transport synthesis (figure 1). The synthesized snowflake type ZnO powder stored in a glass tube is shown in fig 1a. The optical microscope images of this free standing powder at different magnifications can be seen in fig. 1b. Higher magnification image demonstrated that as compared to standard powder (Fig. 1bA), ZnO powder showed a higher order of tetrapod structures and a snowflake-like symmetry (Fig. 1bB). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 1c) demonstrated the geometric orientation and morphology of micro-nano structured powder. A typical cluster of ZnO MNSs can form a well-ordered array of sea urchin-like structures with filopodia type nanospikes (Fig. 1d). Further analysis of the latter by SEM demonstrated that lengths of the spikes are in the range of few microns (2 to 8 μm) but their thicknesses are in the range of 100 nm to 200 nm (Fig. 1e). ZnO based MNSs were subsequently used for the determination of cell toxicity using human fibroblasts (NHDF). Figure 2a shows for the fibroblast viability, a clear concentration dependency of ZnO MNSs toxicity. Concentrations upto 500 μg/ml did not significantly impair the cell viability. Furthermore, the concentration-effect curve for ZnO MNSs treated with UV-light is shifted to the right. The EC50 value derived from the curves increases approximately twofold after UV-light treatment from about 1.3 to 3 mg/ml ZnO. For total protein in cell cultures only a slight concentration-dependent decrease has been measured upon ZnO particle treatment (Fig. 2b). This could be explained by the fact that especially in higher concentrations a layer of ZnO structures cover the cell monolayer, which might have prevented in part the detachment of dead cells upon washing. Nevertheless, in parallel to the viability at higher concentrations UV light pretreated ZnO particles seem to be slightly less toxic than untreated ZnO particles. The concentration of ZnO MNSs was kept below the toxic levels throughout the course of this study.

Fig. 1. ZnO micro nano structures (MNSs).

(a) Synthesis of the ZnO material can be done in large quantities, please note the 23 mm diameter coin. (b) Microscopic image, comparison between a standard powder (A) and the material synthesized here (B). (c) electron micrograph showing the complex geometries. (d) The powder contains a larger quantity of filopodia like structures, which have spikes down to the nanoscale (e).

Fig. 2. Effect of ZnO MNSs on cell viability.

(MTT assay, panel A) and total cell protein (Lowry assay, panel B) of human corneal fibroblasts after 24 h of treatment with ZnO MPs that were either treated (+) or untreated (−) with UV light for one hour. Each symbol represents the mean ± SE of n=3 independent experiments.

3.2. ZnO MNSs significantly blocks HSV-1 entry into glycoprotein D (gD) receptor expressing CHO-K1 cells

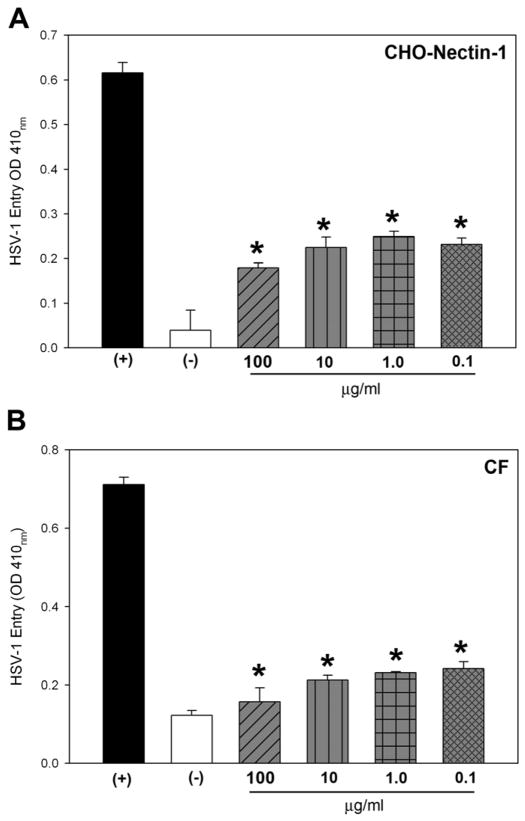

First we determined the effect of ZnO based MNSs on HSV-1 entry into the target cells. HSV-1 entry into cell was determined by using β-galactosidase expressing HSV-1 reporter virus (gL86) into wild type Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells expressing gD receptor nectin-1. As shown in Fig. 3A, HSV-1 pre-incubation with ZnO-MNSs significantly have blocked the viral entry in a dose dependent manner in CHO-K1 cells expressing gD receptors. The control cells treated with 1× PBS (untreated) showed HSV-1 entry. The blocking activity of MNSs was pronounced even at low concentrations (0.01 mg/ml or 100 μg/ml).

Fig. 3. Dosage response of ZnO-MNSs on the inhibition of HSV-1 entry into Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells expressing gD receptor nectin-1.

(A). In this experiment, β-galactosidase-expressing recombinant virus HSV-1 (KOS)gL86 (25 pfu/cell) was pre-incubated with the ZnO-MPs at indicated concentrations (gray bars) or mock-incubated with 1 × phosphate buffer saline (PBS; black bar) for 90 min at room temperature. The uninfected cells were used as negative control (white bar). After 90 min the virus was incubated with CHO-K1 cells expressing gD receptor nectin-1 expressing cells. After 6 hr, the cells were washed, permeabilized and incubated with ONPG substrate (3.0 mg/ml) for quantitation of β-galactosidase activity expressed from the input viral genome. The enzymatic activity was measured at an optical density of 410 nm (OD 410). The value shown is the mean of three or more determinations (± SD). (B).Dosage response of ZnO-MNSs on the inhibition of HSV-1 entry into into natural target cells. Naturally susceptible cells of human corneal fibroblasts (CF) were used in this experiment. The β-galactosidase-expressing recombinant virus HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 (25 pfu/cell) was pre-incubated with ZnO-MPs at indicated concentrations (grey bars) or mock treated with 1 × phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 90 min at room temperature (black bar). The uninfected cells were used as negative control (white bar). After 90 min of ZnO-MPs treatment the virus was incubated with CF cells. After 6 hr, the cells were washed, permeabilized and incubated with ONPG substrate (3.0 mg/ml) for quantitation of β-galactosidase activity expressed from the input viral genome. The enzymatic activity was measured at an optical density of 410 nm (OD 410). Each value shown is the mean of three or more determinations (± SD).

3.3. ZnO MNSs significantly blocks HSV-1 entry into naturally susceptible cells

Next, to further confirm blocking activity of ZnO-MNSs on HSV-1 entry, we used human corneal fibroblasts (CF)-a natural target for HSV-1 infection. The CF expresse HVEM and 3-OST-3 as gD receptors (Tiwari et al., 2006). As shown in Fig. 3 (panel B) the HSV-1 treated with ZnO-MNSs (0.1 mg/ml or 100 μg/ml) showed significant blocking of HSV-1 entry. Similar results were found in HeLa cells that express all the known gD-receptors. In all cases, the mock treated control cells showed HSV-1 entry. The CF and HeLa cells results were consistent with the previous nectin-1 expressing CHO-K1 cells result.

3.4. Pre-treatment of ZnO MNSs with UV illumination enhances anti-HSV-1 activity

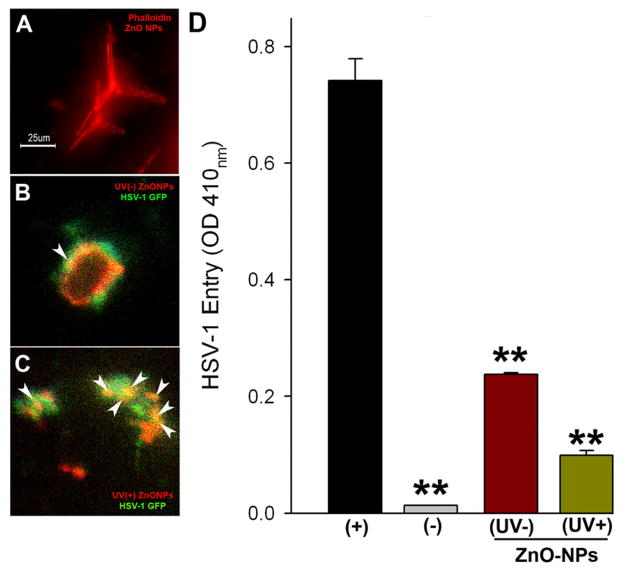

We rationalized that viral entry inhibition property of ZnO MNSs is due to its partial negatively charged oxygen vacancies. Therefore ZnO-MNSs were exposed to UV illumination (Raytech UV-Lamp model R5-FLS-2; Midtown, CT, USA ) for 30 min, which is known to generate additional oxygen vacancies and hence additional negative charge centers on the atomic scale at the surface (Wu and Chen, 2011; Kong et al., 2008). In order to visualize the UV-effect on ZnO MNSs to viral binding, the MNSs were stained red via phalloidin staining (Fig. 4, panel A). The UV treated red-ZnO-MNSs were mixed with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged HSV-1 (VP26). As shown in Fig. 4C the UV-exposed ZnO-MNSs (0.1 mg/ml or 100 μg/ml) showed a significant viral trapping as evident by strong yellow co-localization signal as compared to UV-untreated red-ZnO-MNSs (Fig. 4B). Next, we have also compared if enhanced viral trapping by UV-exposed ZnO-MNSs can translate into enhanced viral inhibition. HSV-1 (KOS) virions were pre-incubated with either UV-treated ZnO-MPs or UV-untreated ZnO-MNSs before infecting target cells. Clearly, the UV exposed particles were able to block HSV-1 entry better (Fig. 4, panel D). This result reinforces the significance of negative charged molecules in HSV-1 entry.

Fig. 4.

(A–C). UV-illumination on ZnO MNSs significantly enhances HSV-1 binding. ZnO-MNSs were exposed to UV illumination for 30 min. MNSs were stained as red via phalloidin treatment (panel A). UV untreated (panel B) and UV-treated (panel C) ZnO MNSs were mixed with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged HSV-1 (VP26). The UV-exposed ZnO-MNSs showing significant HSV-1 trapping as indicated by strong yellow co-localization signal (highlighted by arrows) compared to UV-untreated red-ZnO-MNSs.

D. Pre-incubation of UV-treated ZnO MNSs with HSV-1 significantly blocks viral entry. In this experiment, β-galactosidase-expressing recombinant virus HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 (25 pfu/cell) was pre-incubated for 90 min with the UV pre-treated (+) or untreated (−) ZnO-MPs at 0.1 mg/ml. HSV-1 KOS gL86 mock-incubated with 1 × phosphate buffer saline (PBS; black bar) was used as positive control. The uninfected cells were used as negative control (grey bar). After 90 min the soup was challenged to CF. After 6 hr, the cells were washed, permeabilized and incubated with ONPG substrate (3.0 mg/ml) for quantitation of β-galactosidase activity expressed from the input viral genome. The enzymatic activity was measured at an optical density of 410 nm (OD 410). The value shown is the mean of three or more determinations (± SD).

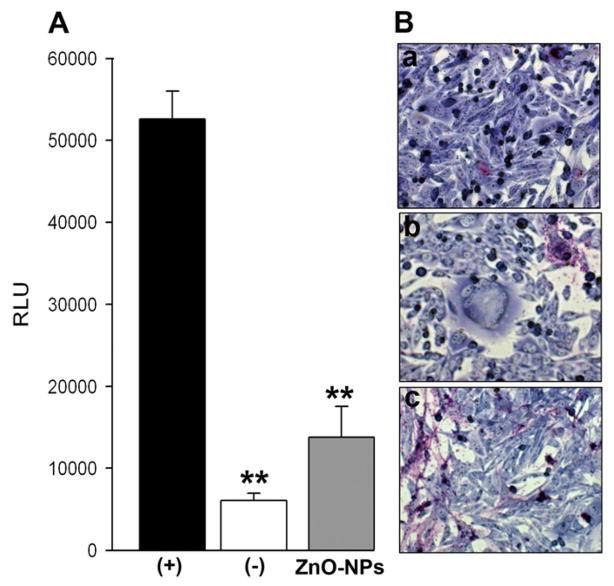

3.5. ZnO MNSs treatment inhibits HSV-1 glycoprotein mediated cell-to-cell fusion and polykaryocytyes formation

We next investigated the effect of ZnO-MNSs during HSV-1 glycoproteins mediated cell to cell fusion. The main emphasis of cell to cell fusion was to demonstrate the viral and cellular requirements during virus-cell interactions and also as means of testing viral spread. We sought to determine whether ZnO MNSs interaction with HSV-1 envelope glycoproteins essential for viral entry affects cell to cell fusion. Surprisingly, effector cells expressing HSV-1 glycoproteins treated with ZnO MNSs (0.01 mg/ ml) impaired the cell to cell fusion in CHO-K1 cells expressing gD receptor nectin-1 (Fig. 5). In parallel, the control untreated effector cells co-cultured with target cells showed expected fusion (Fig.5; black bars in panel A). This response was further confirmed when polykaryocytes formation was estimated. ZnO MNSs treated-effector cells failed to form polykaryons when co-cultured with target cells (Fig. 5; panel B; right panel). The control untreated effector cells efficiently showed larger polykaryons (Fig. 5; panel B; left panel). Our results indicate that the presence of ZnO MNSs significantly reduced viral penetration. We therefore propose that ZnO MNSs can possibly disrupt the viral envelope glycoproteins binding to cell surface HS thereby preventing the virus attachment, surfing, and fusion processes.

Fig. 5. UV treated ZnO MNSs significantly impair HSV-1 glycoproteins induced cell to cell fusion and polykaryocytes formation.

(A). The “effector CHO-K1 cells” expressing HSV-1 glycoproteins (gB, gD, gH–gL) along with T7 plasmid were pre-incubated with 100 μg/ml UV-treated ZnO-MPs or with 1 × PBS for 90 min. The two pools of effector cells (ZnO-MNSs treated and PBS treated) were mixed with target CHO-K1 cells expressing luciferase gene along with specific gD receptor nectin-1. Membrane fusion as a means of viral spread was detected by monitoring luciferase activity. Relative luciferase units (RLUs) determined using a Sirius luminometer (Berthold detection systems). Black bars and grey bars represent 1× PBS treated and ZnO-MNSs treated cells respectively. The effector cells devoid of HSV-1 glycoprotein mixed with target CHO-K1 nectin-1 expressing cells was used a negative control (white bar). Error bars represent standard deviations. * P< 0.05, one way ANOVA. (B). Microscopic visualization of polykaryocyte impairments by ZnO-MNSs. In this experiment effector CHO-K1 cells expressing four essential HSV-1 glycoproteins (gB, gD, gH–gL) were either pre-incubated with ZnO-MNSs or with 1 × PBS for 90 min before they were co-cultured in 1:1 ratio with target nectin-1 expressing CHO-K1 cells for 24 hrs. The cells were fixed (2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaradehyde) for 20 min. and then stained with Gimesa stain (Fluka) for 20 min. Shown are photographs of representative cells (Zeiss Axiovert 200) pictured under microscope at 40 × objective. The upper a panel shows no polykaryocytes formation in absence of HSV-1 glycoprotein (negative control), middle panel b shows significant inhibition of polykaryocytes formation in presence of HSV-1 glycoprotein in effector cells fused with target nectin-1 CHO-K1 cells. Lower panel c shows no polykaryocytes formation in presence of ZnO-MNSs during co-culture of HSV-1 glycoprotein expressing cells with target nectin-1 expressing CHO-K1 cells.

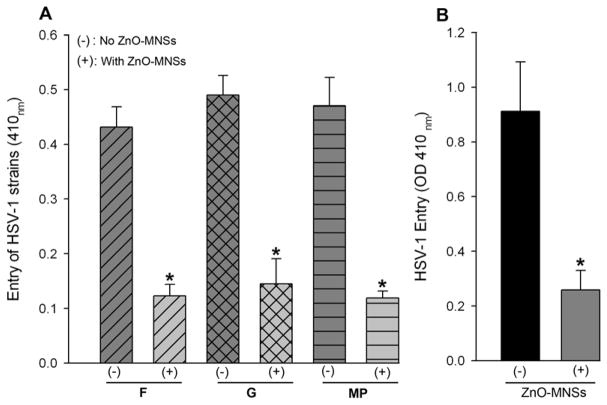

3.6. Clinical and in-vivo significance of ZnO MNSs against HSV-1 entry

The next question was to evaluate the broader significance of UV-treated ZnO MNSs as an anti-HSV agent. We therefore, tested the ability of MNSs to block viral entry in different clinically-relevant strains of HSV (F, G, and MP) (Dean et al., 1994). Here we used nectin-1 expressing CHO Ig8 cells that express β-galactosidase upon viral entry (Montgomery et al., 1996). The virulent strains were pre-incubated with MNSs and then used for infecting the cells. The results from this experiment again showed that MNSs blocked entry of additional HSV strains as evident by ONPG assay (Fig. 6; panel A). Finally, we asked whether an in vivo significance of MNSs could be demonstrated in an animal model. For this we chose embryos from zebrafish, which provide a quick and easy model for testing HSV-1 infection in vivo (Burgos et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 6, panel B, the MNSs were able to prophylactically block infection of the zebrafish embryos as well. This result reaffirms that MNSs hold a strong promise for development as an effective anti-HSV prophylactic agent.

Fig. 6. Significance of ZnO MNSs as anti-HSV agent.

(A). HSV-1 entry blocking activity of MNSs is viral-strain independent. In this experiment clinical strains of HSV (F, G, and MP at 25 pfu/cell) were either pre-incubated with 1 × PBS (−) or with ZnO-MNSs (+) at 10 μg/ml for 90 min at room temperature. After 90 min of incubation the two pools of viruses were incubated on CHO Ig8 cells that express β-galactosidase upon viral entry. The viral entry blocking was measured by ONPG assay. (B). ZnO-MNSs blocks HSV-1 infection in embryo model of zebrafish. In this experiment β-galactosidase expressing HSV-1 (KOS) gL86 reporter virus at 2 × 108 PFU were pre-incubated with 1 × PBS (−) or with 100 μg/ml MNSs (+) for 2 hours before infecting zebrafish embryos for 12 hr. HSV-1 entry in both the groups of embryos were measured by ONPG assay.

4. Discussion

The development of novel strategies to eradicate herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a global public health priority (Superti et al., 2008). While acyclovir and related nucleoside analogues provide successful modalities for treatment and suppression, HSV remains highly prevalent worldwide. The emergence of acyclovir-resistant virus strains, ability of virus to uniformly establish latency coupled with adverse effects of available anti-herpetic compounds provides a stimulus for increased search for new effective antiviral agents that target additional steps in viral pathogenesis such as entry (Schutle et al., 2010; Dambrosi et al., 2010). In addition, the current available treatments are unable to destroy HSV completely and therefore virus remains dormant and keeps activating from time to time to cause various clinical manifestations. Therefore, there is great need to find suitable biocompatible, multifunctional, and low dimensional (scale lengths comparable to viruses) inorganic/organic agents which work to neutralize the virus infectivity, destabilize and possibly dismantle the virus particles.

Recent developments in nanotechnology offer opportunities to re-explore biological properties of known antimicrobial compounds by manipulation of their sizes (Travan et al., 2010). ZnO has long been known for its antibacterial and antifungal properties including the recent report for selective destruction of tumor cells by ZnO nanoparticles and its potential in the development of anti-cancer agents (Rasmussen et al., 2010). In addition, the use of ZnO nanoparticles in sunscreens is one of the most common uses of nanotechnology in consumer products (Beasley et al., 2010). Recently the uses of ZnO nanostructures have been suggested in nonresonant nonlinear optical microscopy in biology and medicine (Kachynski et al., 2008). Cell surface HS is involved in viral pathogenesis including viral binding, transport, and membrane fusion aiding to viral spread (Shukla and Spear, 2001; Akhtar and Shukla, 2009). Therefore the use of ZnO MNSs, in present case, represents a unique approach to antiviral therapy involving competition for the HS chain used by HSV-1 and possibly many other medically important herpesviruses that bind to the cell surface HS (Liu and Thorp, 2002). We initiated the efforts to synthesize structurally defined ZnO MNSs bearing nanoscopic filopodia-like spikes (Fig 1). It was reasoned that ZnO MMNSs containing filipodia like spikes will expand the surface area of partially negatively charged molecules thereby mimicking the overall negative charge present on HS structures. Our initial quantitative viral entry assay revealed that pre-treatment of HSV-1 with ZnO MNSs significantly affected the viral entry at non-toxic concentrations (Fig. 3). UV-irradiated ZnO MNSs were even more potent in blocking HSV-1 entry and spread. Fluorescent imaging experiment further confirmed the quantitative viral entry data that UV-treated ZnO MNSs neutralized the viral infectivity by “viral-trapping” or “virostatic activity”, which was evident from the enhanced accumulation of GFP-tagged virus around MNSs (Fig. 4). The viral trapping activity of MNS was expected as UV-exposure to ZnO spikes enhanced the distribution of negative charge by oxygen vacancies and thereby allowing more viruses to bind. The use functionalized nanoparticles to develop antiviral that act by interfering viral infection, in particular attachment and entry are gaining wide popularity (Tallury et al., 2010; Bowman et al., 2008; Lara et al., 2010; Vig et al., 2008). Already, MNSs are known inhibits cell-to-cell spread of HSV (Baram-Pinto et al., 2009).

The major advantage of ZnO MNSs is their effectiveness at lower concentrations (μg), the low cost of their synthesis, molecular specificity to viral envelope protein without affecting the expression of native HS chain, and ease in designing nanoparticle capsules coated with additional anti-HSV-1 agents including envelop glycoprotein B (gB) and D (gD) based peptides to block HSV-1 entry receptors while keeping the HSV-1 virions trapped to MNSs. ZnO is an integral component of skin, face and lip creams where HSV-1 infection or reactivation leads to painful blisters. Therefore ZnO-MNSs exhibit strong potentials to develop anti-HSV medication for cold sore in the form of protective gel or cream, which may be further activated by the UV-part of the sun light. In addition, such MNSs will become the bench tool to create additional antiviral agents against many other viruses with the conjugation of peptides against specific virus envelope glycoproteins. Furthermore, they can also be used to deliver antiviral peptides with minimal pharmacokinetic problems together with enhanced activity of drug for the treatment of HSV infection.

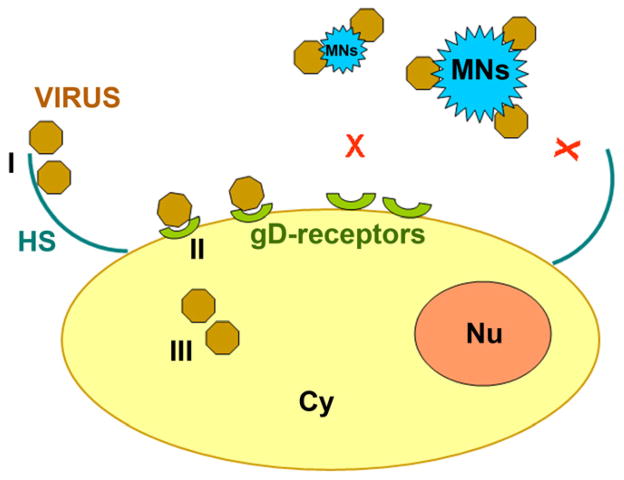

Taken together our findings support the model by which partially negatively charged ZnO MNSs trap the HSV-1 to prevent virus-cell interaction (Fig. 7), which are key steps for successful viral infection of the host cells and therefore, MNSs-based compounds present a useful therapeutic approach. This is further supported by our observation that MNSs also block infection in vivo, in a zebrafish model of HSV-1 infection (Fig. 6B). Additional efficacy of ZnO MNSs is needed to be determined in mammalian models of HSV-1 pathogenesis for potential future use in humans. In summary, our results and the suggested mechanism will encourage the scientific community to further explore the virostatic potential of MNSs for other viruses including additional herpesviruses.

Fig. 7. Model for the ZnO-MNSs based HSV-1 inhibition.

A cartoon illustrates the three major steps (I–III) involved during HSV-1 entry. During step I HSV-1 glycoprotein B (gB) binds to cell surface heparan sulfate (HS), followed by step II in which HSV-1 gD binding to receptors which results virus-cell membrane fusion. The step III involves viral capsid trafficking via cytoplasm (Cy) to reach nucleus (Nu) for viral DNA replication. Interaction of HSV-1 with ZnO-MNSs bearing nanospikes results HSV-1 trapping subsequently affecting early phases of virus-cell interactions and viral entry.

Research Highlights.

Discovery of ZnO-based micro-nanostructures (MNSs) as an efficient anti-HSV agent.

Easy to synthesize particles with MNSs to block HSV-1 infection.

Filopodia-like assembly of these MNSs provides multivalent binding sites for HSV-1.

MNSs block infection both in vitro and in vivo.

MNSs show the promise of development as prophylactic as well as therapeutic anti-HSV-1 agents.

Acknowledgments

Generation of micro-nano structures of ZnO was supported by a DFG grant SFB 855 TP A5, and a Heisenberg-Professorship (R. A.). Y.K.M. gratefully acknowledges the fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt foundation and R.A. the support from the Cluster of Excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces”. This investigation was also supported by Western University of Health Sciences (WUHS) Institutional grant (N12587) and NIH grant (1R15AI088429-01A1) to VT. F.S was supported by IDEA award from WUHS. We sincerely thank Pat Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago) and Prashant Desai (Johns Hopkins University) for the reagents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akhtar J, Shukla D. Viral entry mechanisms: cellular and viral mediators of herpes simplex virus entry. FEBS J. 2009;276:7228–7236. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baram-Pinto D, Shukla S, Gedanken A, Sarid R. Inhibition of HSV-1 attachment, entry, and cell-to-cell spread by functionalized multivalent gold nanoparticles. Small. 2010;6(9):1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/smll.200902384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley DG, Meyer TA. Characterization of the UVA protection provided by avobenzone, zinc oxide, and titanium dioxide in broad-spectrum sunscreen products. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:413–421. doi: 10.2165/11537050-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman MC, Ballard TE, Ackerson CJ, Feldheim DL, Margolis DM, Melander C. Inhibition of HIV fusion with multivalent gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(22):6896–6897. doi: 10.1021/ja710321g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos JS, Ripoll-Gomez J, Alfaro JM, Sastre I, Valdivieso F. Zebrafish as a new model for herpes simplex virus type-1 infection. Zebrafish. 2008;5:323–333. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey L, Spear PG. Infections with herpes simplex viruses. N Eng J Med. 1986;314:686–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603133141105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambrosi S, Martin M, Yim K, Miles B, Canas J, Sergerie Y, Boivin G. Neurovirulence and latency of drug-resistant clinical herpes simplex viruses in animal models. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1000–1010. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean HJ, Terhune S, Shieh MT, Susmarski N, Spear PG. Single amino acid substitutions in gD of herpes simplex virus 1 confer resistant to gD-mediated interference and cause cell type-dependent alterations in infectivity. Virology. 1994;199:67–80. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P, Person S. Incorporation of the green fluorescent protein into the herpes simplex virus type 1 capsid. J Virol. 1998;72:7563–7568. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7563-7568.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Ball MJ, Neumann DM, Azcuv AM, Bhattacharjee PS, Bouhanik S, Clement C, Lukiw WJ, Foster TP, Kumar M, Kafman HE, Thompson HW. The high prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in human trigeminal ganglia is not a function of age or gender. J Virol. 2008;85:8230–8234. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00686-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachynski AV, Kuzmin AN, Nyk M, Roy I, Prasad PN. Zinc Oxide Nanocrystals for Non-resonant Nonlinear Optical Microscopy in Biology and Medicine. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2008;112:10721–10724. doi: 10.1021/jp801684j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye SB, Baker K, Bonshek R, Maseruka H, Grinfeld E, Tullo A, Easty DL, Hart CA. Human herpesviruses in the cornea. Br J Opthalmol. 2000;84:563–571. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.6.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Chu S, Olmedo M, Li L, Yang Z, Liu J. Dominant ultraviolet light emissions in packed ZnO columnar homojunction diodes Appl. Phys Lett. 2008;93:132113. [Google Scholar]

- Lara HH, Ayala-Nuñez NV, Ixtepan-Turrent L, Rodriguez-Padilla C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J Nanobiotechnology. 2010;20(8):1. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Thorp SC. Cell surface heparan sulfate and its roles in assisting viral infections. Med Res Rev. 2002;22:1–25. doi: 10.1002/med.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunological Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg K, Ekblad M, Bergström T, Freeman C, Parish CR, Ferro V, Trybala E. The low molecular weight heparan sulfate-mimetic, PI-88, inhibits cell-to-cell spread of herpes simplex virus. Antiviral Res. 2004;63:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MJ, Akhtar J, Desai P, Shukla D. A role for heparan sulfate in viral surfing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CD, Shukla D. The Importance of Heparan Sulfate in Herpesvirus Infection. Virol Sin. 2008;23:383–393. doi: 10.1007/s12250-008-2992-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CD, Shukla D. A novel function of heparan sulfate in the regulation of cell-cell fusion. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29654–29665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertel P, Fridberg A, Parish M, Spear PG. Cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gB, gD, and gH-gL requires a gD receptor but not necessarily heparan sulfate. Virology. 2001;279:313–324. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman A, Tiwari V, Thakkar JN, Gunnarsson T, Shukla D, Hindle M, Desai U. Structural characterization of a serendipitously discovered bioactive macromolecule, Lignin sulfate. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2822–2832. doi: 10.1021/bm0503064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman A, Tiwari V, Zhao Q, Shukla D, Debnath AK, Desai U. Viral Inhibition Studies on Sulfated Lignin, a Chemically Modified Biopolymer and a Potential Mimic of Heparan Sulfate. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1759–1763. doi: 10.1021/bm0701651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JW, Martinez E, Louka P, Wingett DG. Zinc oxide nanoparticles for selective destruction of tumor cells and potential for drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;9:1063–1077. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2010.502560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl C, Sievers J. Microglia is activated by astrocytes in trimethyltin intoxication. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2005;204:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnati M, Urbinati C. Polysulfated/sulfonated compounds for the development of drugs at the crossroad of viral infection and oncogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2946–2957. doi: 10.2174/138161209789058156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte EC, Sauerbrei A, Hoffmann D, Zimmer C, Hemmer B, Mühlau M. Acyclovir resistance in herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:830–833. doi: 10.1002/ana.21979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear PG, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. Three classes of cell surface receptors for alphaherpesvirus entry. Virology. 2000;275:1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla D, Spear PG. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:503–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Rosenberg RD, Spear PG. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell. 1999;99:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superti F, Ammendolia MG, Marchetti M. New advances in anti-HSV chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:900–911. doi: 10.2174/092986708783955419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallury P, Malhotra A, Byrne LM, Santra S. Nanobioimaging and sensing of infectious diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(4–5):424–37. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar JN, Tiwari V, Desai UR. Nonsulfated, cinnamic acid-based lignins are potent antagonists of HSV-1 entry into cells. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1412–1416. doi: 10.1021/bm100161u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Clement C, Duncan MB, Chen J, Liu J, Shukla D. A role for 3-O-sulfated heparin sulfate in cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:805–809. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Clement C, Xu D, Valyi-Nagy T, Yue BY, Liu J, Shukla D. Role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate as the receptor for herpes simplex virus type 1 entry into primary human corneal fibroblasts. J Virol. 2006;80:8970–8980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00296-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Shukla SY, Shukla D. A sugar binding protein cyanovirin-N blocks herpes simplex virus type-1 entry and cell fusion. Antiviral Res. 2009;84:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Liu J, Valyi-Nagy T, Shukla D. Anti-heparan sulfate peptides that block herpes simplex virus infection in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25406–25415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travan A, Marsich E, Donati I, Benincasa M, Giazzon M, Felisari L, Paoletti S. Silver-polysaccharide nanocomposite antimicrobial coatings for methacrylic thermosets. Acta Biomater. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.024. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig K, Boyoglu S, Rangari V, Sun L, Singh A, Pillai S, Singh SR. Use of Nanoparticles as Therapy for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Inhibition. Nanotechnology 2008: Life Sciences, Medicine & Bio Materials - Technical Proceedings of the 2008 NSTI Nanotechnology Conference and Trade Show; 2008. pp. 543 – 546. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;26:97–109. doi: 10.1086/514600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:541–553. doi: 10.1086/514600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WuDunn D, Spear PG. Initial interaction of herpes simplex virus with cells is binding to heparan sulfate. J Virol. 1989;63:52–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.52-58.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JM, Chen Yi-R. Ultraviolet-Light-Assisted Formation of ZnO Nanowires in Ambient Air: Comparison of Photoresponsive and Photocatalytic Activities in Zinc Hydroxide. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 2011;115(5):2235–2243. [Google Scholar]