Abstract

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) represent the first line of innate immune defense in the lung. AMs use pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to sense pathogens. The best studied PRR is Toll-like receptor (TLR)4, which detects LPS from gram-negative bacteria. The lipid mediator prostaglandin (PG)E2 dampens AM immune responses by inhibiting the signaling events downstream of PRRs. We examined the effect of PGE2 on TLR4 expression in rat AMs. Although PGE2 did not reduce the mRNA levels of TLR4, it decreased TLR4 protein levels. The translation inhibitor cycloheximide reduced TLR4 protein levels with similar kinetics as PGE2, and its effects were not additive with those of the prostanoid, suggesting that PGE2 inhibits TLR at the translational level. The action of PGE2 could be mimicked by the direct stimulator of cAMP formation, forskolin, and involved E prostanoid receptor 2 ligation and cAMP-dependent activation of unanchored type I protein kinase A. Cells pretreated with PGE2 for 24 hours exhibited decreased TNF-α mRNA and protein levels in response to LPS stimulation. Knockdown of TLR4 protein by small interfering RNA to the levels achieved by PGE2 treatment likewise decreased TNF-α mRNA and protein in response to LPS, establishing the functional significance of this PGE2 effect. We provide the first evidence of a lipid mediator acting through its cognate G protein–coupled receptor to affect PRR translation. Because PGE2 is produced in abundance at sites of infection, its inhibitory effects on AM TLR4 expression have important implications for host defense in the lung.

Keywords: innate immunity, pathogen recognition, lipid mediators

Clinical Relevance

The lipid mediator prostaglandin E2 reduces macrophage Toll-like receptor 4 expression by inhibition of translation. The biologic consequence of this is decreased LPS-induced TNF-α transcription and secretion.

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) under steady-state conditions account for 95% of the leukocytes in the lower respiratory tract (1). AMs are key players in controlling pulmonary immune responses (2, 3). During health, they help to maintain a quiescent airspace to preserve the ability of the lung to perform gas exchange (2, 3). However, on challenge with pathogens or pathogen-derived products, such as the gram-negative bacterial cell wall component LPS, AMs initiate a strong inflammatory response involving the release of cytokines, chemokines, and lipid mediators (4, 5).

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), initially discovered in Drosophila melanogaster, that can recognize pathogen components such as flagellin, unmethylated CpG motifs, and peptidoglycan (6, 7). TLR4, which is the most extensively studied TLR, recognizes LPS and possesses structural homology and signaling responses similar to Type 1 IL-1 receptors (8). Signaling from TLR4 activates transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1, which lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines by AMs (9).

Eicosanoids are lipid mediators also produced during the AM response to PRR stimulation. We and others have found that the eicosanoids prostaglandin (PG)E2 and leukotriene (LT)B4 often play opposing roles in regulating AM function, with the former inhibiting and the latter stimulating differentiation, phagocytosis, microbial killing, and proinflammatory cytokine generation (10–12). The capacities of LTB4 and PGE2 to differentially influence macrophage functions have been linked to their abilities to ligate cognate G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) with resulting decreases and increases, respectively, in intracellular levels of the second messenger cAMP (13–15). We have previously shown that, through such increases in cAMP, PGE2 can profoundly and rapidly suppress TLR4 pathway output by inhibiting downstream signaling events (16). However, whether PGE2 and cAMP pathways can also influence the expression of TLR4 is not known.

Here we show that PGE2 decreases TLR4 expression in rat AMs. This effect was mediated not by regulation of tlr4 mRNA but rather by inhibition of its translation. PGE2 can increase cAMP by ligating either of two GPCRs, termed E prostanoid receptors 2 (EP2) and 4 (EP4). This second messenger can act via two effectors, protein kinase (PK)A and guanine nucleotide exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac); the former exists as type I and type II isoforms, based on their distinct cAMP-binding regulatory (R) subunits, and in pools that are either soluble or bound to scaffold proteins termed A kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs). We found that PGE2 reduction of TLR4 protein was mediated by EP2-dependent cAMP activation of unanchored type I PKA. Furthermore, this decrease in TLR4 expression caused by PGE2 was sufficient to decrease TNF-α transcription and secretion in response to AM stimulation with LPS. Thus, our data identify a new means by which lipid mediators, and potentially other GPCR ligands, can modulate TLR4-mediated innate immune responses.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Pathogen-free 125- to 150-g female Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, Portage, MI) were used. Animals were treated according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals with the approval of the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Reagents

RPMI 1640 culture medium and penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B solution were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). PGE2 and EP2 receptor antagonist AH6809 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI); DMSO served as vehicle control. The PKA-specific cAMP analog 6-Bnz-cAMP (N6-benzoyladenosine-3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate), Epac-specific cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2-O-Me-cAMP (8–4-chlorophenylthio)-2’-methyladenosine-3′,5′cyclic monophosphate, PKA RI–selective activator 2-Cl-8-MA, PKA RII–selective activator 6-MBC, PKA RI inhibitor Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS, and PKA RII inhibitor Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS were purchased from Biolog Life Science Institute (Howard, CA). RI/AKAP disruptor peptide RIAD and corresponding control peptide scRIAD were purchased from Anaspec (San Jose, CA). Escherichia coli (055: B5) LPS and SDS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The direct adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin was purchased from EMD Milipore (Darmstadt, Germany). The EP4 receptor antagonist ONO-AE3–208 was a generous gift from ONO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Myristoylated PKI inhibitory peptide was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Isolation and Culture Conditions

Resident AMs from rats were obtained by lung lavage as described previously (17) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 to a final concentration of 8 × 105 to 2 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were allowed to adhere to tissue culture–treated plates for 1 to 2 hours and cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B. The following day, the medium was removed, and cells were treated with compounds of interest at the concentration and times indicated in the figure legends. Human leukemia–derived U937 monocytes (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained for up to 20 passages in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. For experiments, cells were differentiated for 16 hours with 100 nM PMA.

Western Blotting

AMs (8 × 105 to 2 × 106) were plated in 6-well tissue culture dishes and incubated in the presence or absence of the compounds of interest. The cells were then lysed in ice-cold PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad DC protein assay from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Samples containing 30 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE using 8% gels and then transferred overnight to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% BSA, membranes were probed overnight with respective antibodies (TLR4, 1:500; β-actin, 1:10,000). After incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary Ab (titer of 1:10,000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), film was developed using ECL detection (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Relative band densities were determined by densitometric analysis using NIH ImageJ software.

Flow Cytometry

For staining for flow cytometric analysis, AMs were resuspended in PBS, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.5% FCS. Fc receptor–mediated and nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by the addition of excess CD16/CD32 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). TLR4 staining was performed in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature using PE-conjugated antibody against TLR4/CD284 (76B357.1) (Imgenex, San Diego, CA). A FACSCantoII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used for flow cytometric characterization of AMs, and data were analyzed with FlowJo Version 7.6.4 software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

ELISA

Levels of TNF-α were determined by ELISA (R&D Duoset; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) by the University of Michigan Cancer Center Cellular Immunology Core.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Cells were suspended in 1 ml of TRIzol, and RNA was extracted as described previously (18). RNA was amplified by quantitative reverse transcription PCR performed with a SYBR Green PCR kit (Applied Biosystem, Warrington, UK) on a StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Relative gene expression was determined by the ΔCT method, and β-actin was used as reference gene.

RNA Interference

RNA interference was performed according to a protocol provided by Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Rat AMs were transfected using lipofectamine RNAiMax reagent (Invitrogen) with 50 or 100 nM nontargeting SMARTpool control or specific ON-TARGET SMARTpool TLR4 small interfering RNA (siRNA) from Thermo Scientific. After 24 or 48 hours of transfection, AMs were harvested or challenged with LPS for 24 hours.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE from three or more independent experiments unless otherwise specified and were analyzed with the Prism 6.0 statistical program (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). The group means for different treatments were compared by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

PGE2 Causes a Decrease in TLR4 Protein Expression Independent of a Decrease in tlr4 mRNA

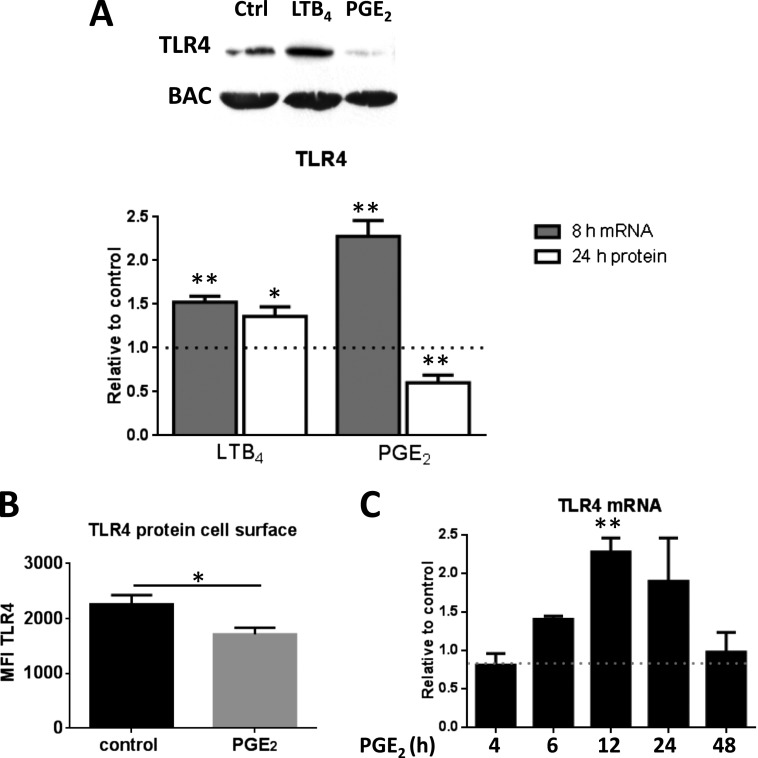

We have reported (14) that PGE2 dose-dependently inhibits AM phagocytosis with a maximal effect at ∼ 1 μM and an IC50 of ∼ 50 nM. Pilot dose–response experiments (not shown) established that 24 hours of treatment with 200 nM PGE2 elicited a reproducible decrease in AM TLR4 protein levels, and this dose was used in all subsequent studies. This effect on TLR4 protein was statistically significant, and the mean reduction was ∼ 40% (Figure 1A). Consistent with prior observations demonstrating opposing regulation of other AM functions, LTB4 at an optimal dose of 100 nM, by contrast, modestly but significantly increased TLR4 expression (Figure 1A). Because functional TLR4 capable of recognizing ligands such as LPS is localized on the cell surface, we used flow cytometry to determine the effect of PGE2 specifically on this functional pool of TLR4. These data confirmed that PGE2 similarly decreased cell surface expression of TLR4 (Figure 1B). Although the increase in TLR4 protein levels in LTB4-treated cells was associated with a parallel increase in tlr4 mRNA levels (assessed at 8 h), the reduction in protein levels in PGE2-treated cells was instead associated with a slight increase in mRNA level (Figure 1A). Time course experiments indicated that at no time point evaluated did PGE2 decrease tlr4 mRNA (Figure 1C). Analysis of the effect of PGE2 on transcript levels of all TLRs at 4 and 24 hours using a Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway PCR Array (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) demonstrated no significant changes (data not shown), consistent with the quantitative reverse transcription PCR results for TLR4.

Figure 1.

Prostaglandin (PG)E2 decreases, whereas leukotriene (LT)B4 increases, Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 protein expression in alveolar macrophages (AMs). (A) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) or LTB4 (100 nM) for 24 hours for protein and for 8 hours for mRNA analysis of TLR4 by Western blot and quantitative PCR (qPCR), respectively. Relative expression of TLR4 protein was normalized for β-actin (BAC) and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). Ctrl = control. (B) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) for 24 hours and analyzed for TLR4 by flow cytometry. Data are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. MFI = mean fluorescence intensity. (C) AMs were treated with PGE2 for 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours and analyzed for tlr4 mRNA by qPCR. Relative expression of tlr4 mRNA was normalized for BAC and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). Data are the means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

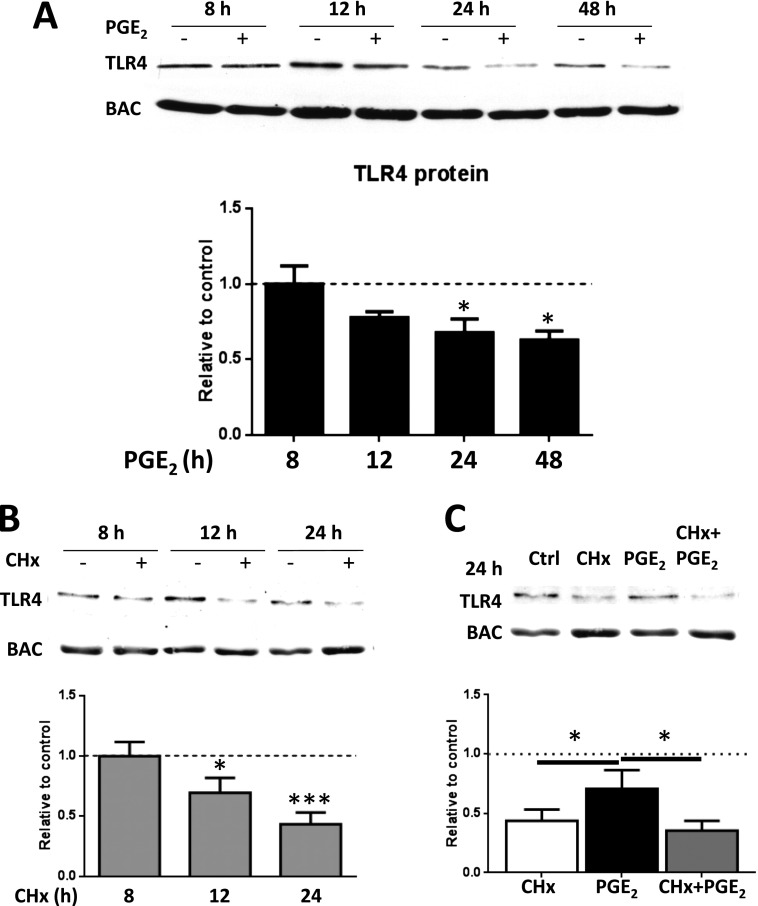

PGE2 Decreases TLR4 by Inhibition of Translation

To further explore the discrepant effects of PGE2 on TLR4 mRNA and protein levels, we first examined the effects of PGE2 on TLR4 protein at a range of time points other than 24 hours. With PGE2 treatment of AMs, there was a time-dependent decrease in TLR4 protein expression over the interval of 12 to 48 hours (Figure 2A). We have recently reported that PGE2 can inhibit global protein translation in macrophages (19). To ascertain whether this decline in TLR4 protein reflected reduced protein synthesis or enhanced degradation by PGE2, we used the prototypical protein translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHx). Under conditions of CHx treatment and hence no translation, we established that TLR4 protein declines in a time-dependent manner with kinetics resembling that seen with PGE2, indicating a half-life of approximately 18 to 24 hours (Figure 2B). At the 24-hour time point, the reduction in TLR4 protein was more pronounced with CHx than with PGE2; however, there was no significant additivity between CHx and PGE2 when AMs were treated with both (Figure 2C). The lack of any additive reduction in TLR4 protein levels by the addition of PGE2 beyond that elicited by CHx suggests that the PGE2-induced decrease in TLR4 levels is mediated by inhibition of protein translation.

Figure 2.

PGE2 decreases TLR4 by translational inhibition. (A) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) for 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 hours and analyzed by Western blot for TLR4 expression. (B) AMs were treated with cycloheximide (CHx) (10 μM) for 4, 8, 12, or 24 hours and analyzed by Western blot for TLR4 expression. (C) AMs were pretreated with CHx for 30 minutes before PGE2 treatment for 24 hours and analyzed by Western blot for TLR4 expression. Relative expression of TLR4 protein was normalized for BAC and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). Data are the means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

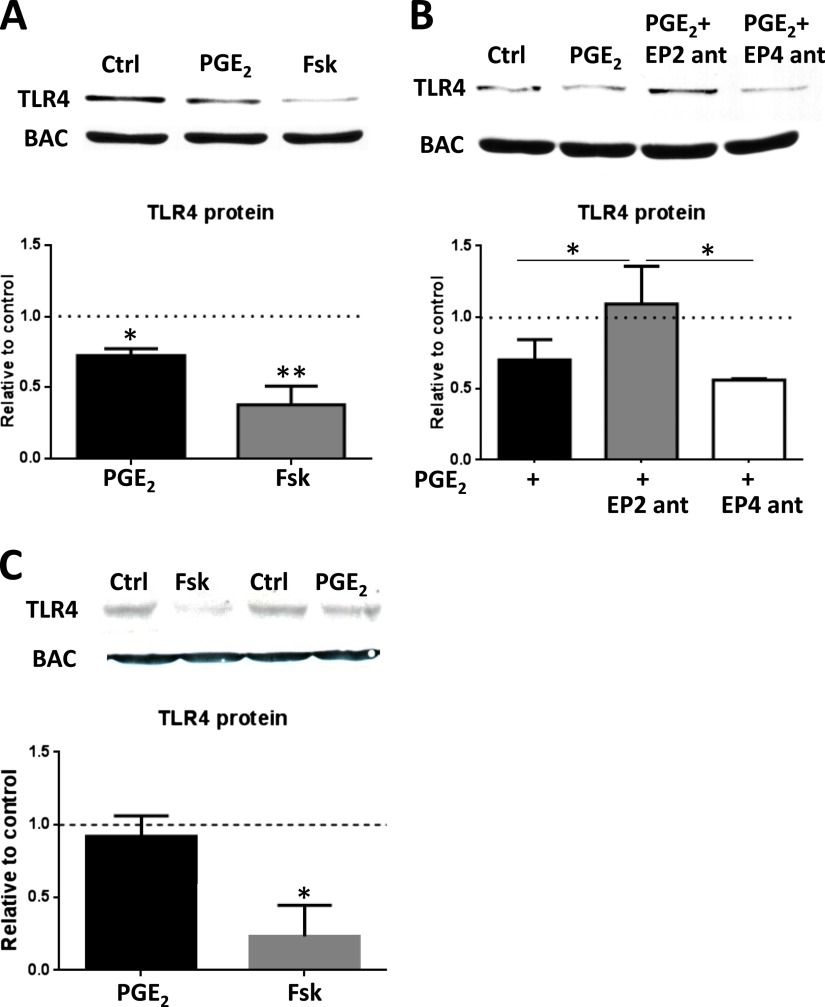

PGE2 Inhibits TLR4 Expression by EP2 Receptor Ligation and Increased cAMP

PGE2 can ligate any of four distinct GPCRs, termed EP1, -2, -3, and -4. EP2 and EP4 are coupled to a stimulatory Gα protein, which stimulates adenylyl cyclase to generate the second messenger cAMP. We have previously demonstrated that PGE2 elicits a dose-dependent increase in intracellular cAMP in rat AMs and that this is mediated primarily via ligation of EP2 (14). To test whether increases in cAMP are capable of reducing TLR4 expression, AMs were treated for 24 hours with forskolin, a compound that increases cAMP by entering the cell and directly activating adenylyl cyclase. Forskolin treatment strongly reduced protein expression of TLR4, suggesting that PGE2 uses a cAMP-coupled receptor to decrease TLR4 (Figure 3A). We used selective EP2 and EP4 antagonists to clarify which of these stimulatory Gα–coupled receptors mediates the actions of PGE2 and found that reduction of TLR4 is mediated through EP2 (Figure 3B). The relevance of the cAMP inhibitory effect on TLR4 expression to human cells was examined in the U937 human monocytic cell line differentiated with PMA. Although there was a dramatic and statistically significant suppression of TLR4 expression by forskolin, PGE2 itself had no effect (Figure 3C). A previous report demonstrated that differentiation of U937 cells with PMA caused a decrease in EP2 expression and signaling (20). Thus, although these cells may not be suitable for exploring the effects of PGE2–EP2 actions on TLR4, they do indicate that when the GPCR is bypassed and adenylyl cyclase is activated directly by forskolin, the inhibitory effects of cAMP on expression of this PRR in human cells are still apparent.

Figure 3.

PGE2 decreases TLR4 protein by an EP2-cAMP signaling pathway. (A) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) or forskolin (Fsk) (100 μM) for 24 hours and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4 expression. (B) AMs were treated with PGE2 or with the EP2-selective antagonist AH6809 (1 μM) or the EP4-selective antagonist ONO-AE3–208 (1 μM) for 30 minutes followed by PGE2 for 24 hours. AM lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4 expression. Relative expression of TLR4 protein was normalized for BAC and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). (C) Human monocytic cell line U937 was differentiated to macrophages with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and treated with PGE2 (100 nM) or forskolin (Fsk, 100 μM) for 24 hours and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4 expression. Relative expression of TLR4 protein was normalized for BAC and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). Data are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

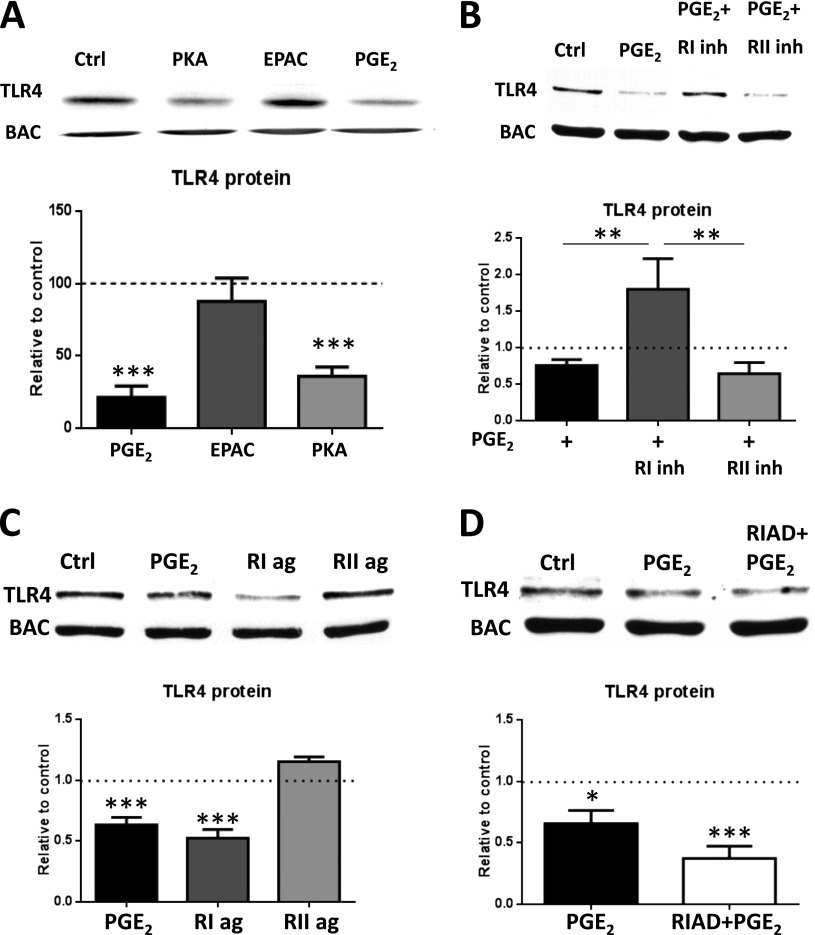

PGE2 Acts through Unanchored Type I PKA to Decrease TLR4 Protein

The cAMP effectors PKA and Epac can mediate distinct inhibitory effects of cAMP in AMs (21). To determine which cAMP effector pathway PGE2 uses to decrease TLR4 protein levels, cAMP analogs with selectivity for activation of PKA or Epac were used. PKA agonist–treated cells showed a statistically significant decrease in TLR4 protein expression, whereas Epac agonist–treated cells showed no effect (Figure 4A). Selective agonists and inhibitors of types I and II PKA were used to determine which PKA R isoform mediates PGE2 inhibition of TLR4 protein levels. Pretreatment of AMs with a PKA-RI inhibitor for 30 minutes prevented the ability of PGE2 to decrease TLR4 protein, whereas a PKA-RII inhibitor did not (Figure 4B). Additionally, a PKA-RI agonist was able to mimic the decrease in TLR4 protein elicited by PGE2, but a PKA-RII agonist was not (Figure 4C). On the basis of these results, we conclude that PGE2 uses type I PKA to inhibit TLR4 protein production.

Figure 4.

Unanchored type I PKA is responsible for the suppression by PGE2 of TLR4 protein. (A) AMs were treated for 24 hours with the PKA-specific cAMP analog 6-Bnz-cAMP (PKA, 500 μM), the Epac-specific cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2-O-Me-cAMP (Epac, 500 μM), or PGE2 (200 nM) and analyzed by Western blot for TLR4 expression. (B) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) or pretreated for 30 minutes with PKA RI inhibitor Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS (10 μM) or PKA RII inhibitor Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS (10 μM) for 30 minutes, treated with PGE2 for 24 hours, and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4. (C) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM), PKA RI–selective activator 2-Cl-8-MA (10 μM), or PKA RII–selective activator 6-MBC (10 μM) for 24 hours and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4. (D) AMs were treated with PGE2 (200 nM) or pretreated with the RI/AKAP disruptor peptide RIAD (25 μM) for 30 minutes and then treated with PGE2 for 24 hours before Western blot analysis for TLR4. Relative expression of TLR4 protein was normalized for BAC and expressed relative to control (DMSO) (represented in the graph as a dashed line). Data are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

AKAPs are a family of proteins that serve as scaffolds to target PKA to specific microdomains and thereby enhance proximity to particular substrates (22). To determine whether inhibition of TLR4 expression involves an AKAP-anchored pool of type I PKA, we pretreated cells with RIAD, a peptide that selectively disrupts interactions between AKAPs and PKA-RI (Figure 4D). RIAD did not inhibit PGE2 actions, suggesting that reduction of TLR4 by PGE2 is mediated by an unanchored pool of type I PKA.

PGE2 Reduction of TLR4 Dampens TNF-α Production on LPS Treatment

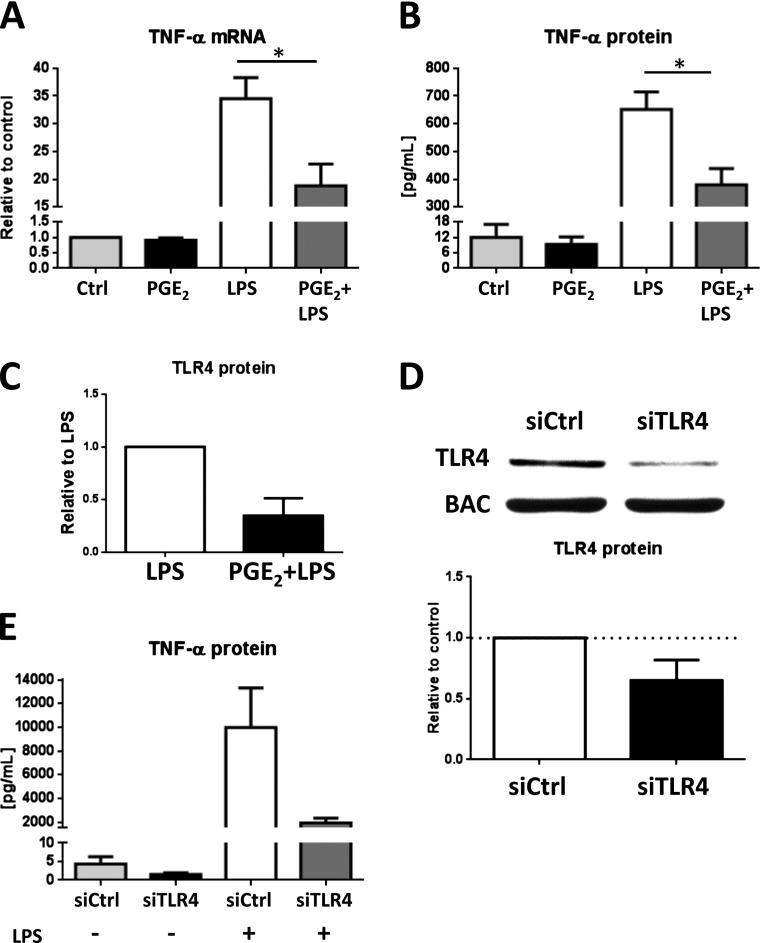

To determine the functional significance of the decrease in TLR4 protein elicited by PGE2, we examined the LPS-induced generation of TNF-α. AMs were pretreated for 24 hours with PGE2 and then treated with LPS for another 8 or 24 hours. Compared with PGE2-untreated cells, AMs pretreated with PGE2 expressed less TNF-α mRNA at 8 hours (Figure 5A) and secreted less TNF-α protein measured by ELISA at 24 hours (Figure 5B) in response to stimulation with LPS. AMs pretreated with PGE2 before LPS stimulation likewise exhibited decreased TLR4 levels (Figure 5C). PGE2 treatment alone did not decrease TNF-α mRNA or protein, indicating that the effects observed in Figures 5A and 5B are not due to a direct inhibition of TNF-α transcription or translation by PGE2. PGE2 has been previously demonstrated to inhibit TLR4 signaling, which can result in inhibition of TNF-α release (23, 24). To determine whether the degree of reduction of TLR4 protein elicited by PGE2 is sufficient on its own to be associated with functional consequences, knockdown of TLR4 by RNA interference was performed. Treatment of AMs for 24 hours with TLR4 siRNA reduced TLR4 protein to a degree (∼ 40%) similar to that caused by PGE2 (Figure 5D). AMs pretreated with siRNA in this manner and then treated with LPS for 24 hours generated substantially less TNF-α (Figure 5E). These data suggest that the degree of down-regulation of TLR4 elicited by PGE2 is sufficient to impair the TLR4-mediated inflammatory response independent of the known ability of PGE2 to interfere with TLR4 signaling (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Reduction in TLR4 protein by PGE2 causes decreased LPS-induced TNF-α mRNA and protein. (A, B) AMs were pretreated with PGE2 or DMSO vehicle control for 24 hours and then treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or media alone for another 8 hours before quantification of TNF-α mRNA in cell lysates by qPCR and for 24 hours before quantification of TNF-α protein in supernatants by ELISA. (C) AMs were pretreated with PGE2 or DMSO vehicle control for 24 hours and then treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or media alone for another 24 hours before quantification of TLR4 protein in cell lysates by Western blot. (D) AMs were treated with control small interfering RNA (siRNA) or TLR4 siRNA (50 μM) for 24 hours. Cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis for TLR4 and β-actin. (E) AMs were pretreated with control siRNA or TLR4 siRNA for 24 hours and then treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or medium control. Supernatants were harvested, and TNF-α protein was measured by ELISA. Data are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Scheme depicting inhibition of TLR4 translation by PGE2. (1) PGE2 ligation of the EP2 receptor results in activation of Gs α subunit (2), which leads to conversion of ATP to cAMP by adenyl cyclase (3). cAMP binds to cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) type II-α regulatory subunit (4), resulting in dissociation of the PKA catalytic subunit (5), whose activity decreases TLR4 protein translation (6). Decreased TLR4 protein translation results in lower levels of TLR4 protein in the cell and more importantly at the cell surface (7). On LPS stimulation (8), this lower level of cell surface TLR4 protein leads to weaker TLR4 signaling (9), resulting in inhibition of TNF-α transcription (10). AC, adenyl cyclase; C, the catalytic subunit of PKA; EP2, E prostanoid 2 receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; RII, cAMP-dependent protein kinase type II.

Discussion

Lung infections are responsible for more morbidity and mortality worldwide than infections in any other organs (25). This underscores the importance of understanding the regulation of innate immunity in the lung. AMs serve as the first line of immune defense in the pulmonary alveolar space, and TLR4 is one of the most important mechanisms for pathogen recognition by these cells. Finally, because PGE2 is produced in great abundance at sites of infection and inflammation, its influence on innate immune responses mediated by TLR4 is of significant interest. Here we demonstrate for the first time that PGE2 diminishes TLR4 protein expression in resident rat AMs, attenuating the capacity for proinflammatory cytokine generation on subsequent LPS stimulation. This action of PGE2 was mediated by inhibition of TLR4 translation, rather than transcription, and involved a signaling cascade consisting of EP2 ligation and cAMP activation of unanchored PKA-RI. The ability of increased intracellular cAMP to reduce TLR4 expression was also observed in human monocyte–like cells. Decreased TLR4 levels resulted in lower transcription and secretion of TNF-α on LPS stimulation. These data are summarized conceptually in Figure 6. This finding represents a new mechanism by which PGE2 dampens TLR4 responses.

We have previously shown that PGE2, also via a EP2-cAMP-PKA axis, can modulate cytokine production initiated by TLR4 ligation when added to AMs at the same time as LPS (16). This effect involves PKA regulation of TLR4 signaling pathway components that culminate in the activation of NF-κB. The phenomenon described here would be expected to similarly and additively dampen TLR4 responses, but it involves a delayed action of PGE2, which requires a number of hours. That this effect was independent of changes in tlr4 mRNA levels excludes reduced transcription and reduced message stability. The similarity in kinetics and the lack of additivity with CHx suggest that PGE2 exerted its effect not by promoting degradation of TLR4 protein but by inhibiting translation. This is consistent with our recent study (19) that reported that PGE2, via PKA, inhibits global protein translation in macrophages and other cell types, an effect that was mediated by PKA inhibition of the translation enhancer, mammalian target of rapamycin, and its activation/phosphorylation of the translation repressor ribosomal protein S6. To our knowledge, this represents the first demonstration of TLR4 expression being regulated at the translational level in any cell type.

The effects of PGE2 differed from those of its lipid mediator counterpart, LTB4, in the directionality and mechanism of its effects on TLR4 expression. LTB4 enhanced TLR4 protein expression on AMs, and this was paralleled by a concomitant increase in tlr4 mRNA. LTB4 has previously been shown to promote AM responses to TLR4 ligation by increasing expression of the TLR adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (26), thereby increasing TLR4-induced signaling. Its ability to up-regulate expression of TLR4, as demonstrated here, represents another mechanism by which it would be expected to enhance responses to TLR4 ligands. Taken together, our data indicate that lipid mediators can regulate TLR4 expression at the translational (PGE2) or pretranslational (LTB4) levels. Because the actions of PGE2 were our primary focus in this report, the precise mechanisms by which LTB4 up-regulates tlr4 mRNA remain to be explored. However, because LTB4 has been shown to increase expression of PU.1 (27), the major transcription factor for tlr4 (28), we speculate that it may in this way increase transcription of tlr4.

Among the numerous NF-κB–dependent gene products induced in macrophages stimulated with LPS are cyclooxygenase-2 (29) and microsomal PGE synthase-1 (30), two enzymes that catalyze the sequential conversion of arachidonic acid to PGE2. It is very likely, therefore, that PGE2, which is produced during the host response to LPS, acts in a feedback loop to attenuate TLR responses. This may help to prevent inflammatory responses from persisting and causing tissue damage, but it is also evident that exaggerated production of or signaling by PGE2 could, through reduced expression of TLR4 (shown herein) and TLR4 signaling (shown previously), impair innate immune defense, as has been reported in animal models of lung infection (31–33). The ability of PGE2 to down-regulate TLR4 could also potentially explain the phenomenon of LPS tolerance, in which prior exposure to LPS can cause reduced secretion of TNF-α in response to a subsequent challenge (34). Indeed, PGE2 has been implicated in the phenomenon of immunoparalysis after sepsis (35), and down-regulation of TLR4 expression could contribute to this.

Although the ability of LTB4 to enhance and of PGE2 to decrease TLR4 expression in AMs has obvious implications for pulmonary innate immunity, the role of TLR4 extends beyond microbial recognition. TLR4 can be activated by a variety of ligands that are not derived from microbes (36). These include high mobility group box 1, which can mediate acute lung injury (37), and low-molecular-weight hyaluronan, which can contribute to airway inflammation in asthma (38) and fibrotic lung injury (39). Other endogenous TLR4 ligands, such as heparan sulfate (40), fibrinogen (41), and several heat shock proteins (42, 43), play important roles in various disease states. Down-regulation of TLR4 expression by endogenous PGE2 would be expected to decrease innate immune responses and tissue injury in response to these danger-associated molecules. Finally, because up-regulation of TLR4 contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases (44), ventilator-induced lung injury (45, 46), and Th2 immune responses involved in allergic asthma (38, 47–50), the ability of PGE2 to down-regulate TLR4 expression might have broad clinical and therapeutic relevance.

Several questions stimulated by this work remain unanswered. Further studies should verify if the results we have obtained in rat AMs can be reproduced in human cells. Although our effort to address this in U937 cells was limited by the fact that these cells are unresponsive to PGE2, they did verify the ability of increases in cAMP, achieved independently of EP2-mediated actions of PGE2, to decrease TLR4 expression. It is unknown whether the effects of PGE2 on TLR4 described herein in AMs apply to resident macrophages from other anatomic sites. Likewise, it is not known if PGE2 exerts a similar effect in macrophages recruited to the lung. Finally, it remains to be determined if PGE2 similarly inhibits protein translation of TLRs other than TLR4 or of other classes of PRRs.

In conclusion, we have identified a PGE2-EP2-cAMP–type I PKA axis that down-regulates TLR4 expression on primary resident AMs, leading to impairment in TLR4 responses, as reflected by TNF-α production. This effect is mediated by inhibition of translation of the TLR4 protein. The ability of an endogenously generated GPCR ligand to regulate TLR4 can influence protective and deleterious responses to ligation of this PRR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) (Z.Z.), by American Lung Association Senior Research Fellowships (Z.Z., E.B.), and by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL94311 and R01 HL58897 (M.P.-G.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0495OC on March 6, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin HH, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:901–944. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt PG. Down-regulation of immune responses in the lower respiratory tract: the role of alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;63:261–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thepen T, Van Rooijen N, Kraal G. Alveolar macrophage elimination in vivo is associated with an increase in pulmonary immune response in mice. J Exp Med. 1989;170:499–509. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizgerd JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:716–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin TR, Frevert CW. Innate immunity in the lungs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:403–411. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-090JS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immunity. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:338–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters-Golden M, McNish RW, Hyzy R, Shelly C, Toews GB. Alterations in the pattern of arachidonate metabolism accompany rat macrophage differentiation in the lung. J Immunol. 1990;144:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serezani CH, Kane S, Medeiros AI, Cornett AM, Kim SH, Marques MM, Lee SP, Lewis C, Bourdonnay E, Ballinger MN, et al. PTEN directly activates the actin depolymerization factor cofilin-1 during PGE2-mediated inhibition of phagocytosis of fungi. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morato-Marques M, Campos MR, Kane S, Rangel AP, Lewis C, Ballinger MN, Kim SH, Peters-Golden M, Jancar S, Serezani CH. Leukotrienes target F-actin/cofilin-1 to enhance alveolar macrophage anti-fungal activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28902–28913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peres CM, Aronoff DM, Serezani CH, Flamand N, Faccioli LH, Peters-Golden M. Specific leukotriene receptors couple to distinct G proteins to effect stimulation of alveolar macrophage host defense functions. J Immunol. 2007;179:5454–5461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2004;173:559–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SP, Serezani CH, Medeiros AI, Ballinger MN, Peters-Golden M. Crosstalk between prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 regulates phagocytosis in alveolar macrophages via combinatorial effects on cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2009;182:530–537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SH, Serezani CH, Okunishi K, Zaslona Z, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Distinct protein kinase A anchoring proteins direct prostaglandin E2 modulation of Toll-like receptor signaling in alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8875–8883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters-Golden M, Bathon J, Flores R, Hirata F, Newcombe DS. Glucocorticoid inhibition of zymosan-induced arachidonic acid release by rat alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:803–809. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okunishi K, DeGraaf AJ, Zaslona Z, Huang SK, Peters-Golden M. Inhibition of protein translation as a novel mechanism for prostaglandin E2 regulation of cell functions. FASEB J. 2014;28:56–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-231720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng L, An S, Goetzl EJ. Independent down-regulation of EP2 and EP3 subtypes of the prostaglandin E2 receptors on U937 human monocytic cells. Immunology. 1995;86:620–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Serezani CH, Luo M, Peters-Golden M. Cutting edge: macrophage inhibition by cyclic AMP (cAMP): differential roles of protein kinase A and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP-1. J Immunol. 2005;174:595–599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:959–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hubbard LL, Ballinger MN, Thomas PE, Wilke CA, Standiford TJ, Kobayashi KS, Flavell RA, Moore BB. A role for IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-M in prostaglandin E2-induced immunosuppression post-bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2010;184:6299–6308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Acquisto F, Sautebin L, Iuvone T, Di Rosa M, Carnuccio R. Prostaglandins prevent inducible nitric oxide synthase protein expression by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB activation in J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welsh DA, Mason CM. Host defense in respiratory infections. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:1329–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serezani CH, Lewis C, Jancar S, Peters-Golden M. Leukotriene B4 amplifies NF-kappaB activation in mouse macrophages by reducing SOCS1 inhibition of MyD88 expression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:671–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI43302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serezani CH, Kane S, Collins L, Morato-Marques M, Osterholzer JJ, Peters-Golden M. Macrophage dectin-1 expression is controlled by leukotriene B4 via a GM-CSF/PU.1 axis. J Immunol. 2012;189:906–915. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rehli M, Poltorak A, Schwarzfischer L, Krause SW, Andreesen R, Beutler B. PU.1 and interferon consensus sequence-binding protein regulate the myeloid expression of the human Toll-like receptor 4 gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9773–9781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CC, Chiu KT, Sun YT, Chen WC. Role of the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages: involvement of cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31559–31564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz-Munoz MD, Osma-Garcia IC, Cacheiro-Llaguno C, Fresno M, Iniguez MA. Coordinated up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 transcription by nuclear factor kappa B and early growth response-1 in macrophages. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Moser C, Louboutin JP, Lysenko ES, Weiner DJ, Weiser JN, Wilson JM. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates innate immune responses to Haemophilus influenzae infection in mouse lung. J Immunol. 2002;168:810–815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abel B, Thieblemont N, Quesniaux VJ, Brown N, Mpagi J, Miyake K, Bihl F, Ryffel B. Toll-like receptor 4 expression is required to control chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:3155–3162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schurr JR, Young E, Byrne P, Steele C, Shellito JE, Kolls JK. Central role of toll-like receptor 4 signaling and host defense in experimental pneumonia caused by gram-negative bacteria. Infect Immun. 2005;73:532–545. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.532-545.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shemi D, Kaplanski J. Involvement of PGE2 and TNF-alpha in LPS-tolerance in rat glial primary cultures. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brogliato AR, Antunes CA, Carvalho RS, Monteiro AP, Tinoco RF, Bozza MT, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M, Kunkel SL, Vianna-Jorge R, et al. Ketoprofen impairs immunosuppression induced by severe sepsis and reveals an important role for prostaglandin E2. Shock. 2012;38:620–629. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318272ff8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beg AA. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors: implications for regulating inflammatory and immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:509–512. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng Y, Yang Z, Gao Y, Xu H, Zheng B, Jiang M, Xu J, He Z, Wang X. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates acute lung injury induced by high mobility group box-1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang J, Jiang D, Jung Y, Xie T, Ingram J, Church T, Degan S, Leonard M, Kraft M, Noble PW.Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in human asthma J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011128403–411.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Jiang D, Liang J, Meltzer EB, Gray A, Miura R, Wogensen L, Yamaguchi Y, Noble PW. Severe lung fibrosis requires an invasive fibroblast phenotype regulated by hyaluronan and CD44. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brennan TV, Lin L, Huang X, Cardona DM, Li Z, Dredge K, Chao NJ, Yang Y. Heparan sulfate, an endogenous TLR4 agonist, promotes acute GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:2899–2908. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-368720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smiley ST, King JA, Hancock WW. Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2001;167:2887–2894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vabulas RM, Ahmad-Nejad P, da Costa C, Miethke T, Kirschning CJ, Hacker H, Wagner H. Endocytosed HSP60s use toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 to activate the toll/interleukin-1 receptor signaling pathway in innate immune cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31332–31339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asea A, Rehli M, Kabingu E, Boch JA, Bare O, Auron PE, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15028–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu B, Yang Y, Dai J, Medzhitov R, Freudenberg MA, Zhang PL, Li Z. TLR4 up-regulation at protein or gene level is pathogenic for lupus-like autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2006;177:6880–6888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaneker M, Joosten LA, Heunks LM, Snijdelaar DG, Halbertsma FJ, van Egmond J, Netea MG, van der Hoeven JG, Scheffer GJ. Low-tidal-volume mechanical ventilation induces a toll-like receptor 4-dependent inflammatory response in healthy mice. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:465–472. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182aef1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu G, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates neutrophil sequestration and lung injury induced by endotoxin and hyperinflation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:194–201. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181bc7c17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Lindsey JY, Stober VP, Polosukhin VV, Blackwell TS, Schwartz DA, Foster WM, Hollingsworth JW. TLR4 is necessary for hyaluronan-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness after ozone inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:666–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 48.Nigo YI, Yamashita M, Hirahara K, Shinnakasu R, Inami M, Kimura M, Hasegawa A, Kohno Y, Nakayama T. Regulation of allergic airway inflammation through Toll-like receptor 4-mediated modification of mast cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2286–2291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510685103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trompette A, Divanovic S, Visintin A, Blanchard C, Hegde RS, Madan R, Thorne PS, Wills-Karp M, Gioannini TL, Weiss JP, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan AM, Chen HC, Pochard P, Eisenbarth SC, Herrick CA, Bottomly HK. TLR4 signaling in stromal cells is critical for the initiation of allergic Th2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Immunol. 2010;184:3535–3544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]