Purpose

Caregivers of children with mental health problems report feeling physically and psychologically overwhelmed1 and have high rates of depression because of the caregiving demands of their children.2 Research on the needs of these caregivers and on interventions to ameliorate their stress and mental health concerns is needed. Recruiting primary caregivers of children with mental health problems, however, can be particularly difficult because of the stigma associated with mental health problems. Further, the enormous time commitment, energy expenditure, stress, and burden involved in caring for these children often make it difficult for caregivers to have the time or energy to participate in research studies. Difficulty recruiting caregivers of children with mental health problems can impede needed research with this population. There is a need to better understand how to effectively recruit these caregivers into research studies in order to better inform development of effective interventions to help decrease their caregiving challenges.

Research is a CNSs core competency and active participation in the conduct of research is within the CNS scope of practice.3 CNSs have the training and skills to take on a variety of roles in research projects including as primary investigators, co-investigators, project managers, research nurses, and data collectors. In these roles, CNSs facilitate the recruitment of research participants. CNSs who work in mental health, therefore, maybe called upon to recruit caregivers of children with mental health problems. Therefore, the information provided in this manuscript will be informative to these CNSs as they develop cost-effective recruitment strategies. Additionally, CNSs know their clinical team colleagues (e.g., social workers) very well and can identify as well as rally them to facilitate the recruitment efforts for the research study. The CNS are also instrumental to keeping both administrators and clinicians engaged and committed to a research project by continually updating them about study progress and presenting final reports.

The purpose of this article is to describe strategies used to recruit participants into a randomized, wait-list control intervention study that focused on improving problem-solving skills in primary caregivers of children with mental health problems. Results of each recruitment strategy are examined, along with lessons learned in the process of recruiting the participants.

Background

Most of the literature on recruitment for intervention studies has focused predominantly on treatments for physical diseases such as cancer and heart disease.4,5 Research on recruitment related to mental health problems has focused on caregivers of older adults who have Alzheimer’s disease,6–8 and few have addressed recruitment strategies for caregivers of children with mental health problems.9 Information obtained from caregivers of persons with physical illness or adults with Alzheimer’s disease cannot be generalized to caregivers of children with mental health problems because they have different caregiving situations. Caregivers of children with mental health problems, for example, have the added burden and unpredictable stressors of managing problematic behaviors associated with these disorders.10 Behavior problems such as hyperactivity, aggression, self-destructive behaviors, and delinquency require caregivers’ constant surveillance, control, and exertion.11 Consequently, caregivers of children with mental health problems are often left with little time, energy, or motivation to take on additional tasks such as participating in research.6 Therefore, it is important to identify cost-effective recruitment strategies to increase their potential participation in research.

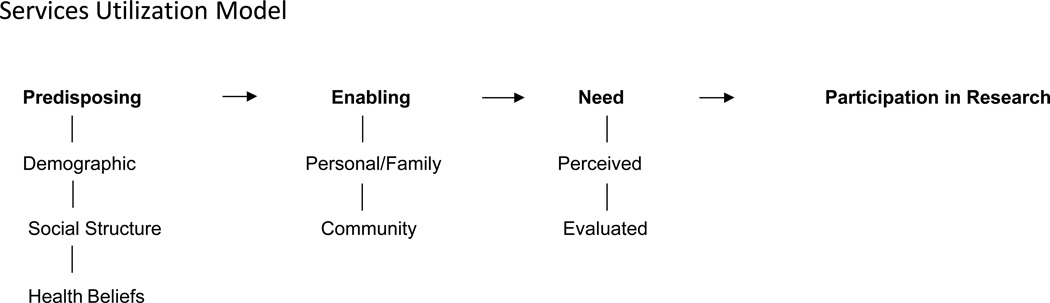

Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization (ABM) was adapted to guide our reflections and organize the lessons learned from the recruitment challenges we encountered in our research study on a problem-solving intervention (Figure 1). The purpose of the ABM is to identify factors that either facilitate or impede health services utilization.12 According to the model, the use of health services is affected by three factors: predisposing, enabling, and need. Applying these factors to recruitment challenges in mental health research, we argue that the caregivers’ access to and participation in a research study may also be influenced by (a) predisposing factors such as demographics (age, gender), social structure (education, occupation), and health beliefs about research; (b) enabling factors such as personal or family awareness or knowledge of the research study, time available to participate, access to research facilities in the community; and (c) the perceived relevance of the research to the caregivers or their situation.12 In addition, caregivers’ access to and participation in a research study may be influenced by health care provider-related factors, such as the providers’ evaluation of the relevance of the research, competing demands for clinical responsibilities, and time.13 The recruitment efforts in this study focused primarily on enabling factors and need factors of the caregivers and healthcare providers, which, unlike predisposing factors, are relatively changeable.12

Figure 1.

Proposed Recruitment Model: Adapted from the Andersen’s Behavioral Health Services Utilization Model

Recruitment strategies for intervention research include health system referral, community outreach, social marketing, and other types of referrals.6,9 Health system recruitment includes dissemination of information about the research study by health care providers in pre-identified and collaborating health agencies. Community outreach recruitment strategies include networking with community and religious leaders and organizations; conducting community presentations, meetings and health screenings; and setting up booths during community events to pass out information about the study.9 Social marketing recruitment strategies include the use of radio, newspapers, magazines, newsletters, and flyer advertisements (ads). Additional recruitment strategies include referral by friends, family, and other participants in the study.

Recruitment is a process that requires flexibility and on-going evaluation. There is a need to balance the cost of recruitment with the resulting number of participants obtained. Based on a systematic review of the literature, Uybico and colleagues9 found that social marketing (e.g., radio and newspaper ads), alone or in combination with community outreach, yielded the highest number of participants in 9 of 11 studies reviewed. Lindenstruth, Curtis, and Allen14 reported that recruiting in internal newsletters and seeking health care professional referrals were less expensive but yielded fewer participants than social marketing strategies. The health care providers’ perceptions of the relevance of the research, competing demands for clinical responsibilities, and time availability all influence the providers’ likelihood of recommending to their clients that they participate in any given study.13

Description of the Project

The study was a problem-solving intervention for primary caregivers of children with mental health problems, Building Our Solutions and Connections (BOSC). BOSC was adapted from the IMPACT Project,15 which is an empirically supported cognitive-behavioral and skills-building intervention. BOSC is an innovative telephone-based intervention designed to increase caregivers’ personal control, improve problem-solving attitudes and skills, and decrease their symptoms of depression and burden.16,17 The proposed sample size was 50 (n = 25 for the BOSC group and 25 for the wait-list control or WLC group). To account for attrition, the investigators planned to oversample (n = 66).

The recruitment plan, which was implemented in November of 2009, was modeled after a successful plan utilized in a prior cross-sectional study using the same population. Recruitment efforts in the prior study resulted in 155 participants.2,18 Recruitment efforts were also informed by findings from a pilot study conducted to test the BOSC intervention. In the pilot study, we experienced a low turn-out rate of interested participants who had to travel to a major medical center and found challenges in parking and finding the meeting location. The first of the nine BOSC interventions was, therefore, conducted face-to-face at a location that was easily accessible for the participant (i.e., a reserved room at a nearby library) and that had free parking. The remaining eight interventions and data collections were completed by telephone. The research team had planned to recruit caregivers over a period of four-and-a-half months from community mental health centers (CMHC) and other agencies providing mental health services for children, as well as through responses to newsletter ads of mental health advocacy groups or flyers.

Initially, information was primarily disseminated via flyers that were shared through the principal investigator’s contacts in the community, including two large community mental health centers that provided outpatient and school-based services, a children’s hospital outpatient psychiatric unit, and mental health advocacy groups. For example, one health care agency placed flyers at the check-in desk with other patient information so that caregivers could pick them up as they registered for their child’s appointment. This agency also shared study information with their health providers, particularly therapists, who could inform their clients about the study. These therapists were located in multiple settings including outpatient clinics and school-based mental health offices.

Potential participants were encouraged to call the principal investigator (PI) or project manager’s office to learn more about the study. The PI or project manager contacted potential participants, conducted an initial screening to identify if potential participants qualified for the study, and provided additional information about the study. Recruitment from the CMHC and other sites failed to meet recruitment goals. At six months into the study, 44 participants had been assessed for eligibility for the study and 24 were eligible to enroll, creating a need to revise and expand the recruitment. Guided by the literature, the ABM, the pilot study, and field experiences from existing recruitment strategies, the research team expanded the scope of the initial recruitment efforts. Approval was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board for all proposed changes to the initial recruitment plans.

Health system referrals

The research team built upon and expanded its network of connections in the community. The team met with research collaborators at the main CMHC to review and discuss ways to increase recruitment rates at this site. First, the research team visited the clinic site and met face-to-face with the support staff supervisor and her staff. It was agreed that the support staff would hand out study flyers to all family caregivers who visited the clinic for scheduled appointments. When this did not yield any significant increase in number of participants assessed for eligibility and/or recruited, the research team enlisted the CMHC intake specialist to recruit potential participants for the study and reimbursed the agency for her time. This strategy was consistent with the ABM because the payment offset any lost productivity accrued by her recruitment efforts. She was also asked to approach colleagues to ask if they knew of caregivers of children who might be eligible. She then contacted each eligible caregiver on the phone or at the clinic. Additionally, the CMHC agreed to put study flyers in new patient packets.

The research team also identified and contacted more health care providers in the community and sought approval to widely disseminate study flyers to their clients. The team communicated regularly with these professionals to keep them aware of the study. This strategy was consistent with the ABM, which suggests that health care providers should evaluate the relevance of the research study for their clients. Recruitment efforts were enhanced by meeting with the health care providers and continually answering questions about the research study.

Community outreach

Recruitment flyers were posted at libraries, school hallways, parking garages at the university, and a church community. Information about the study was shared at community meetings. For example, the PI and a co-investigator attended a large advocacy support group for parents of children with mental health problems and presented findings from preliminary studies about the well-being of primary caregivers. Members of research team also attended two conferences and health fairs with CMHC staff during which the team member distributed the study flyers and answered questions relevant to the study. The costs associated with community outreach, such as conference fee and development of the flyers, were only about $144 plus the paid hourly rate for the research assistants.

Social networking

The research team strengthened its social networking strategies by improving the quality of the study flyer and developing a briefer flyer with larger print. Advertisements were also placed in the city’s major newspaper, the university newspaper, and e-mail newsletters. The total estimated cost for advertising in paper media was $1,186. Additional advertisements were placed in newsletters published by three different local agencies that served children with mental health needs (e.g., the local chapter of the National Alliance for Mentally Ill persons [NAMI]) at no charge. However, the research assistants were reimbursed for their time distributing the newsletter ads to these agencies.

Increased efforts aimed at health systems referrals, community outreach, and advertisements did not substantively increase the number of participants needed for the study. The research team, therefore, began radio ads as its main social marketing tool. The PI contacted two local radio stations in an effort to reach a wider audience and, consistent with the ABM, increased information and awareness about the BOSC study.7,8,19 We chose the two radio stations based on a record of past recruitment success and their geographic reach. After two weeks and a successful response from the initial radio ads, a second radio station was utilized in an effort to reach a broader audience.

The first radio station’s average weekly listenership included 145,000 adults over the age of 18. Seventy-two percent of the listeners were employed full or part time; 62% were homeowners; 59% had children in the household; and 53% had some college education or more. This radio station served a more ethnically and socio-economically diverse geographic area compared to the second station, which served a relatively more conservative area.

The second radio station’s average weekly listenership included 143,000 adults over the age of 25. Sixty-five percent of the listeners were employed full or part time and 57% had some college education or higher. Each radio station was given the study flyer which they used to create a radio ad with one station using background music. Each radio station ran the study ad multiple times in the summer of 2010. The total cost for the radio ads was $4,500.

Outcomes from the Radio Ads

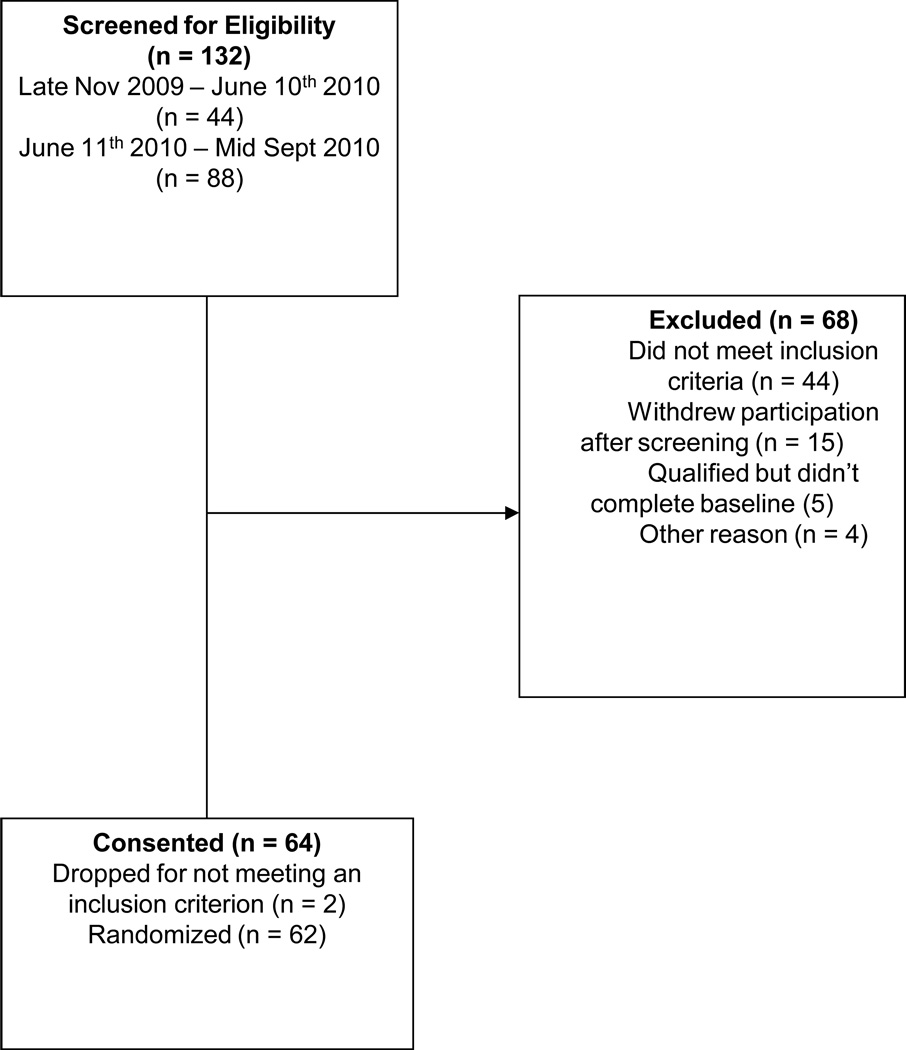

Forty-four participants were assessed for eligibility over the initial six-and one half months (late November 2009 to June 10th, 2010) of recruitment, whereas the number of participants assessed for eligibility doubled during the three months using the radio ads (Figure 2). The time for recruitment was greater than originally anticipated. The difficulty encountered in recruiting participants for the BOSC intervention study was unexpected. Therefore, there was no systematic plan to ask participants how they learned about the study. However, the research team noted a marked surge in calls from interested participants as soon as the radio ads began to air, although calls declined with subsequent repetition of the same ads. Consequently, we do not have a clear count of the actual number of participants recruited through the radio ads. We are confident, however, based on our observations that the radio ads accounted for significant increase in recruitment.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment for the BOSC study

Research findings about the effectiveness of radio ads compared to other forms of advertisement or recruitment efforts have varied, which may be partially attributed to differences in the populations of interest.20 Consistent with our findings, radio ads generated more than 64% of the calls in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of chiropractic care for lumber stenosis20 and 71.1% of the inquiries that yielded successful recruitment in a chemo-prevention clinical trial involving ex-smokers.21 Other researchers have also reported that radio ads were much more expensive than other recruitment strategies.14,22 However, without the radio ads, our recruitment goals were not likely to be met.

We speculate that radio ads were the most effective recruitment strategy in our study for a number of reasons: First, the radios ads ran during the summer and more caregivers might have been at home and, therefore, likely to hear the radio ads. Also, it could be that caregivers felt that they really needed support because their child was out of school and the level of caregiving demands was greater than when the child was in school. Finally, it may be that caregivers had more time to listen to the radio while driving but less time to read a paper. Given this finding, CNSs should really consider the use of radio ads to recruit caregivers of children with mental health problems for intervention research studies.

What we learned during our health system referral recruitment efforts also offer a number of practical considerations for CNSs. The intake worker at the CMHC who recruited for the BOSC study contributed significantly to increasing the number of caregivers who were recruited. We believe that reimbursing the CMHC agency for a staff member’s time dedicated to the recruitment was pivotal to this increase. CNSs who are involved in research projects may also consider having multiple recruitment sites or partners, if appropriate for the study because it increases the number of potential participants. Although the research team in the BOSC study anticipated that 75% of participants would be recruited from the CMHC, this was not the case. The actual number recruited in this way was about 38.6%. It was, therefore, helpful that the team had pre-identified other potential recruitment sites. Contact persons at these sites were enlisted at the planning stages of the study to collaborate with the research team in its recruitment efforts

In a previous study, we successfully recruited participants using community outreach. However, similar efforts seemed to be less productive in the BOSC study. Community outreach efforts may be more useful for establishing collaborations between the research team and the community than for direct recruitment of participants.9 CNSs should seriously consider using community outreach to establish the researcher’s credibility as an advocate for the population of interest and may, therefore, have long-term recruitment benefits relative to future studies.

The BOSC study presented recruitment challenges not encountered in our previous cross-sectional study of caregivers of children with mental health problems. The fact that the BOSC study was longitudinal in design and, therefore, required a longer time commitment by the participants suggests that the ease and effectiveness of recruitment strategies vary between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, an important point for CNSs to consider in planning their studies.

Relevance of the ABM

Consistent with findings from other studies, our work demonstrated that the ABM12 is an appropriate framework that CNSs could use to guide and modify recruitment strategies for intervention research.6 Understanding the target population and factors that facilitated or hindered their participation, as well as identifying the services provided by different health providers and the way services were organized and delivered to their patients were vital to our recruitment efforts. These efforts enabled both the caregivers and health care professionals to learn about the study and to understand its relevance and the importance of participation.

Interpretation/conclusion

The purpose of this report was to share lessons learned from recruitment challenges experienced while conducting a longitudinal, randomized controlled intervention study (BOSC) with caregivers of children with mental health problems to better inform CNSs and others who participate in the conduct of research studies. Recruitment of these caregivers can be particularly challenging because of the burden of their caregiving responsibilities and the stigma associated with mental health disorders. Recruitment in the BOSC study was successful because we were flexible and made decisions consistent with the ABM. Recruitment was enhanced by focusing on enabling and need factors to increase access to information about the study and to boost recruitment. Though the radio ads were the most effective recruitment strategy for the caregivers in this study, we do not have enough information to recommend that radio ads should be used alone for recruitment of this population. CNSs should consider using radio ads in combination with other traditional methods such as talking with caregivers at treatment sites to boost awareness and facilitate participation in these studies. CNSs need to remember that recruitment is an iterative process and should be continually evaluated for its effectiveness and revised throughout the recruitment period as needed.

Implications

Because we did not expect the challenges with recruitment, there was no systematic tracking of how caregivers heard about the study or how many were randomized per recruitment strategy. This is a major gap of this report and underscores that CNSs who study this population of caregivers need to systematically track which recruitment strategies lead to the greatest number of participants screened, eligible, and enrolled into studies.9 The next logical step in recruitment research for caregivers of children with mental health problems is to do formal effectiveness/cost analyses to determine which recruitment strategies are most cost-effective.

References

- 1.Oruche U, Gerkensmeyer J, Stephan L, Wheeler C, Hanna K. Described Experience of Primary Caregivers of Children With Mental Health Needs. Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerkensmeyer J, Perkins S, Scott E, Wu J. Depressive Symptoms Among Primary Caregivers of Children With Mental Health Problems: Mediating and Moderating Variables. Arch of Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22(3):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National CNS Competency Task Force. [Accessed March 19th, 2012];Clinical Nurse Specialist Core Competencies: Executive Summary 2006–2008. 2010 http://www.nacns.org/docs/CNSCoreCompetenciesBroch.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell A, Bastani R, Glenn B, Mojica C, Chang LC. An Experimental Test of the Effect of Incentives on Recruitment of Ethnically Diverse Colorectal Cancer Cases and Their First-Degree Relatives into Research Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(10):2620–2625. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pressler S, Subramanian U, Shaw R, Gradus-Pizlo I. Recruitment in Patients With Heart Failure: Challenges in Recruitment. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(3):198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelman C. Learning From Recruitment Challenges: Barriers to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research Participation for Latinos With Symptoms of Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2010;53(1):94–113. doi: 10.1080/01634370903361847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher-Thompson D, Singer L, Depp C, Mausbach B, Cardenas V, Coon D. Effective Recruitment Strategies for Latino and Causcasian Dementia Family Caregivers in Intervention Research. Am J of Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:484–490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Arean P. Recruitment and Retention of Latino Dementia Family Caregiver in Intervention Research: Issues to Face, Lessons to Learn. Gerontologist. 2003;43:45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uybico S, Pavel S, Gross C. Recruiting Vulnerable Populations into Research: A Syatematic Review of Recruitment Interventions. Society of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins D, Bailey S, Pearce J. Factors Associated With Functioning Style and Coping Strategies of Families With A Child With An Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism. 2005;9(2) doi: 10.1177/1362361305051403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oeseburg B, Jansen D, Groothoff J, Reijneveld S. Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Adolescents With Intellectual Disability With and Without Chronic Diseases. J Intell Disabil Res. 2010;54(1):81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen R. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinshaw S, Hoagwood K, Jensen P, et al. AACAP 2001 Research Forum: Challenges and Recommendations Regarding Recruitment and Retention of Participants in Research Investigations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):1037–1045. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000129222.89433.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindenstruth K, Curtis C, Allen J. Recruitment of African American and Menopausal Women in Clinical Trials: The Beneficial Effects of Soy Trial Experience. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):938–942. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagel D, Imming J, Cyr-Provost M, Noel P, Arean P, Unutzer J. Role of Behavioral Health Professionals in Collaborative Stepped Care Treatment Model Depression in Primary Care: Project IMPACT. Families, Systems & Health. 2002;20(3):265–277. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorwick D, Dunn G, Ayuso-Mateos J, Dalgard O, Page H, Lehtinen V. Problems Solving Treatment and Group Psychoeducation for Depression: Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. BMJ. 2000;321:1450–1454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch D, Tamburrino M, Nagel R, Smith M. Telephone-Based Treatment for Family Practice Patients With Mild Depression. Psychol Rep. 2004;94:785–792. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.785-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerkensmeyer J. Problem Solving Intervention for Primary Caregivers of Children With Mental Health Problems: Pre-Pilot Study. Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blue Chip Health Care Marketing. New Survey from Blue Chip Patient Recruitment Reveals Best Practices for Using Social Media in Clinical Trials. 2011 Article A259889439. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cambron JA, Dexheimer JM, Chang M, Cramer GD. Recruitment Methods and Costs for a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Chiropractic Care for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Single-Site Pilot Study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kye SH, Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Adams B, Nie W-X, Mao JT. Recruitment strategies for a lung cancer chemoprevention trial involving ex-smokers. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2009;30(5):464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDermott MM, Domanchuk K, Dyer A, Ades P, Kibbe M, Criqui MH. Recruiting participants with peripheral arterial disease for clinical trials: Experience from the Study to Improve Leg Circulation (SILC) J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(3):653–659. e654. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]