Abstract

A nanoporous membrane system with directed flow carrying reagents to sequentially attached enzymes to mimic nature’s enzyme complex system was demonstrated. Genetically modified glycosylation enzyme, OleD Loki variant, was immobilized onto nanometer-scale electrodes at the pore entrances/exits of anodic aluminum oxide membranes through His6-tag affinity binding. The enzyme activity was assessed in two reactions—a one-step “reverse” sugar nucleotide formation reaction (UDP-Glc) and a two-step sequential sugar nucleotide formation and sugar nucleotide-based glycosylation reaction. For the one-step reaction, enzyme specific activity of 6–20 min–1 on membrane supports was seen to be comparable to solution enzyme specific activity of 10 min–1. UDP-Glc production efficiencies as high as 98% were observed at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, at which the substrate residence time over the electrode length down pore entrances was matched to the enzyme activity rate. This flow geometry also prevented an unwanted secondary product hydrolysis reaction, as observed in the test homogeneous solution. Enzyme utilization increased by a factor of 280 compared to test homogeneous conditions due to the continuous flow of fresh substrate over the enzyme. To mimic enzyme complex systems, a two-step sequential reaction using OleD Loki enzyme was performed at membrane pore entrances then exits. After UDP-Glc formation at the entrance electrode, aglycon 4-methylumbelliferone was supplied at the exit face of the reactor, affording overall 80% glycosylation efficiency. The membrane platform showed the ability to be regenerated with purified enzyme as well as directly from expression crude, thus demonstrating a single-step immobilization and purification process.

Keywords: biomimetic enzyme immobilization, membrane−electrode, glycosyltransferase, glycosylation, enzyme purification, sequential reactions

Enzymes are biocatalysts capable of accelerating a range of chemical transformations relevant to materials production, pharmaceutical development, and renewable energy and often present an attractive “green” alternative to conventional synthetic strategies.1 In their natural cellular/tissue environment, enzymes often assemble and/or colocalize to form multienzyme complexes or serial networks to expedite multistep processes in part via minimization of substrate/product loss via diffusion2−5 and/or to maintain exquisite control of highly reactive intermediate species.6−8 Additionally, the reliance upon sequential multienzyme processes and/or enzyme complexes enables metabolic control of an overall process via focused allosteric and/or competitive regulation of key gate-keeper enzymes within the process by substrate/product/cofactor concentrations.9 Inspired, in part, by nature’s logic, enzyme immobilization platforms offer the potential to mimic natural multienzyme systems,10−15 particularly in systems where convective flow can be used to efficiently direct products and intermediates in a sequential manner rather than depending upon Fickian diffusion.

A variety of immobilization formats for multienzyme processes have been developed. For example, simple nitrilotriacetate immobilization of His6-tagged enzymes, as exemplified by the “superbead” approach reported by Wang and co-workers, offered improvements in enzyme stability and product isolation in the context of multienzyme sugar nucleotide synthesis and utilization processes.16,17 However, such random immobilization strategies lack systematic control and rely on stochastic transport within the dense surface layer that is mechanistically analogous to homogeneous solution. Kunitake and co-workers18 constructed alternating layers of glucose oxidase and peroxidase with layer-by-layer film adsorption on a quartz slide and subsequently demonstrated sequential activity. Though discrete enzymatic reactions were spatially separated into layers in this example, the system lacked convective flow for directing the overall sequence of reactions. Bhattacharyya and co-workers recently developed reactive stacked membranes with a top membrane containing immobilized glucose oxidase and bottom membrane containing ferrihydrite/iron oxide nanoparticles for the degradation of toxic organics in water.19 This membrane system has the advantage of using convective flow to direct the potentially damaging peroxide produced at the enzyme away to the Fe catalyst activation sites in the lower membrane layer. Building from these examples, we anticipate an idealized structure to derive from membrane pore bearing immobilized enzymes in a sequential order at nanometer-scale proximity. In this context, porous anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) membranes offer an attractive platform for enzyme immobilization and biosensor applications20−25 due to its high pore density, uniform pore size, and good resistance to nonspecific protein adsorption. The precise placement of gold electrodes on an AAO membrane would also make it possible for tunable immobilization of sequential enzyme cascades. Gold plating has been successfully used to tune pore size and add surface chemistry on track-etched and AAO membranes.26,27 Thus, multiple enzymes could feasibly be immobilized, in a sequential manner, on these two nanometer-scale electrodes to perform multistep reactions at the membrane entrance and exit respectively to mimic natural multienzyme sequential processes.

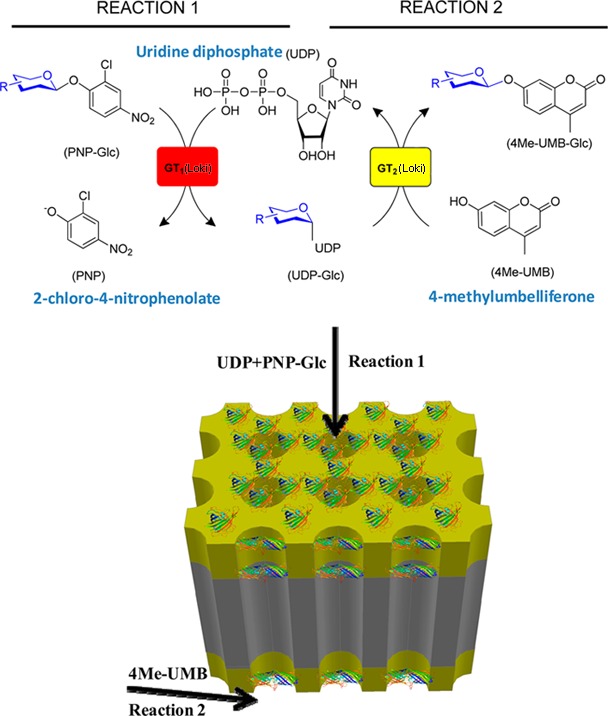

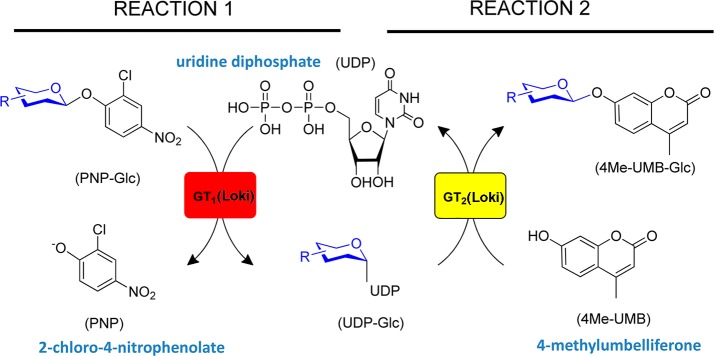

As a simple model to demonstrate multistep immobilized enzyme-catalyzed catalysis using AAO membranes, we have selected the recently reported glycosyltransferase (GT)-catalyzed transglycosylation process reported by Thorson and co-workers.28−34 This system is based upon the development of simple aromatic glycosides as efficient donors in glycosyltransferase-catalyzed reactions for both sugar nucleotide formation (i.e., the “reverse” of a conventional GT-catalyzed reaction) and subsequent sugar nucleotide-mediated glycoside formation, wherein the use of 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl glycoside donors also offered a convenient colorimetric screen to enable the directed evolution of enhanced GTs with broad substrate permissivity.31−34 Thus, this system offers a convenient model of a simple two-step enzyme-catalyzed process—2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl glycoside-driven sugar nucleotide formation and sugar nucleotide-mediated glycoside formation—for immobilization studies. Herein we report the successful immobilization of the His6-tagged engineered glycosyltransferase OleD Loki variant on nanometer-scale electrodes at the pore entrance and exit of AAO membrane through Ni-NTA,35 which improves both enzyme activity and stability while eliminating unwanted hydrolytic side reactions known to occur at higher enzyme concentrations in the solution phase. In addition, discrete control of each independent step of the two-step sequential reaction was demonstrated via selective reagent feedstock composition exposure of the top and/or bottom surface of an immobilized membrane/electrode system. Finally, a convenient one-step immobilization and purification of N-His6-OleD Loki variant directly from crude Escherichia coli Loki heterologous overproduction extract was demonstrated to enable rapid immobilized catalyzed regeneration. Cumulatively, this study highlights the utility of the AAO membrane/electrode system as a support architecture for controlling multistep enzymatic processes.

Results and Discussion

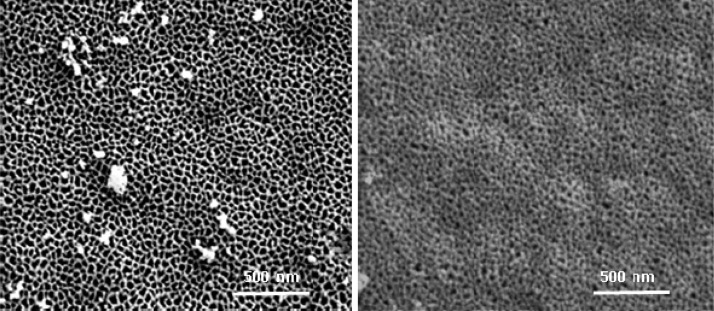

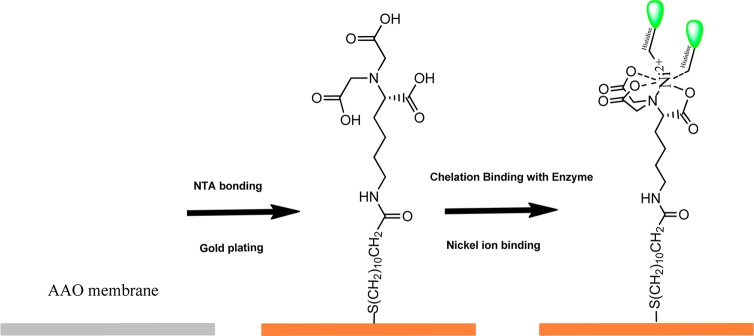

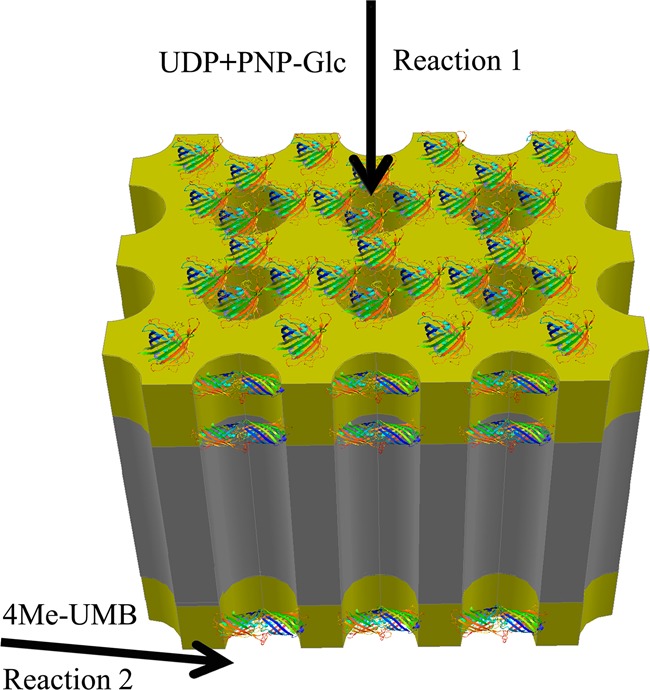

The primary membrane design challenge is to localize enzyme functionality at pore entrances and exits to enable directional flow of substrates/products over the enzyme active sites in an efficient manner. Commercially available 20 nm nominal diameter AAO membranes are asymmetric with a thin porous layer at the top with a diameter of 27 nm and a bulk pore structure mainly composed of 200 nm diameter straight channel monoliths. The depth that gold sputtering can reach within the top pore neck is around 20 nm, and gold electroless plating occurs only on that deposited gold seed layer. The pore diameter of AAO membranes can be controlled by changing electroless plating time, as shown in Figure 1. Fifty minutes of electroless plating time gave the desired average pore diameter of 10 nm, matching the GT dimer length of 9.2 nm.39 With this geometry GT1 (the first GT as shown in Figure 3), the 10 nm pore entrance will block the pore, thus excess solution GT1 cannot pass through the pore to the other side of the AAO membrane after binding.38 This allows a second distinct enzyme, GT2, to be immobilized on the 200 nm pore side of the AAO membrane to enable a directional sequential series of reactions. The process for N-His6-OleD immobilization on a gold surface (Figure 2) enabled immobilization of a total amount of 30 μg of enzyme per monolayer coating based upon Bradford assay to afford a surface “concentration” of 3 g/mL immobilized enzyme within the 9.8 × 10–6 mL electrode volume.

Figure 1.

SEM images of bare AAO membrane and electroless-plated AAO membrane on top surface sputtered seed layer. AAO membrane pore size was controlled by gold electroless plating to match enzyme dimensions to increase efficiency of convective flow over the enzyme.

Figure 3.

Model reactions utilized to assess the immobilized platform. Reaction 1 is a 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl glucose (PNP-Glc)-driven glycosyltransferase-catalyzed “reverse” reaction to produce the desired sugar nucleotide UDP-Glc. Reaction 2 is a standard glycosyltransferase-catalyzed glycosylation of the model acceptor 4Me-UMB, where the UDP-Glc from reaction 1 serves as the sugar donor in a sequential reaction. For the current study, reaction 1 occurs on the top face while reaction 2 occurs at the bottom face of the reactor membrane.

Figure 2.

Enzyme immobilization process onto Au electrodes at AAO pore entrances. In the presence of excess N-His6-enzyme for 24 h (see Experimental Section), the 20 nm pore size surface is routinely coated with 30 μg of enzyme, affording a local surface concentration of 3 g/mL.

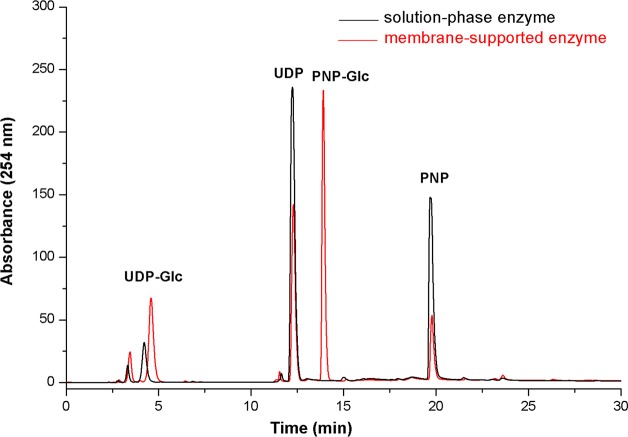

To demonstrate the immobilized activity of the enzyme on the membrane system, we first compared GT-catalyzed UDP-Glc production (Figure 3, reaction 1) in a standard solution-phase reaction31,33,34 to that of the membrane-supported format. The solution-phase reaction contained 2.6 mM glycoside donor, 1 mM UDP, and 100 μg/mL OleD Loki in a total volume of 200 μL of Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.5) and was incubated at 25 °C for 12 h. The much higher than standard (typically 0.5–2.0 μg/mL) enzyme concentrations employed in this solution-phase comparator reaction were utilized to better reflect the high local concentration of the immobilized system (estimated as 3 g/mL as previously described). The corresponding immobilized reaction utilized an identical reagent/reaction mixture (lacking enzyme) pumped through the OleD Loki-loaded membrane at 1 mL/h over 4 h at 25 °C. UDP-Glc production in the solution-phase reaction and the collected eluent from the membrane-supported reaction was determined by HPLC (Supporting Information Figure S7 and Figure 4). As controls, identical reactions wherein OleD Loki was replaced by N-His6-tagged CalC (an enediyne self-resistance protein devoid of GT activity)40,41 were utilized to distinguish any potential non-enzymatic contributions to UDP-Glc production.

Figure 4 highlights the outcome of this initial reaction 1 comparison and reveals a total 40% yield of UDP-Glc in the membrane-bound enzyme format compared to 12% in the solution phase and no reaction in the comparator CalC-based negative controls. Interestingly, significant amounts of PNP-Glc were still present in the membrane-bound eluent, suggesting the 1 mL/h flow rate to be too fast for optimal residence time. In contrast, PNP-Glc was exhausted in the solution-phase reaction, and corresponding low UDP-Glc yield was attributed to undesired PNP-Glc and UDP-Glc hydrolysis that unexpectedly occurred at high enzyme concentrations and extended reactions times. Supporting Information Figure S2 shows the direct hydrolysis of a solution of desired product (UDP-Glc) being hydrolyzed by the enzyme to UDP (reaction conditions: 0.5 mM UDP-Glc, 100 μg/mL Loki, 100 μL of Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 25 °C). Supporting Information Figures S3 shows the formation of hydrolysis product under the conditions for the first reaction (reaction conditions: 0.5 mM UDP-Glc, 100 μg/mL Loki, 100 μL of Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 25 °C). While a reduction of enzyme concentration and shorter reaction times in the solution-phase format can circumvent this unwanted effect, the immobilized format offers the opportunity to fine-tune residence time via adjusting the flow rate to afford optimal UDP-Glc production in reaction 1 at high concentrations/throughput without allowing the subsequent hydrolysis reaction. Within this context, the substrate residence time can be calculated based upon [(pore area × electrode thickness)/volume flow rate]. Thus, we expect to achieve the best reaction yields by matching an optimal flow rate with an enzyme’s specific kinetics where slower enzymes would require an additional increase in path length.

Figure 4.

Representative HPLC analysis of UDP-Glc production (reaction 1) using solution-phase enzyme and membrane-supported enzyme. The solution-phase reaction mixture contained 2.6 mM glycoside donor, 1 mM UDP, 100 μg/mL OleD Loki in a total volume of 200 μL 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5 and was incubated at 25 °C for 12 h. The immobilized reaction contained 4 mL of the same reagent mix (lacking solution-phase OleD Loki) injected through the membrane containing a total of 30 μg of immobilized OleD Loki at a flow rate of 1 mL/h at 25 °C for 4 h. Resulting reactions were subsequently analyzed by HPLC.

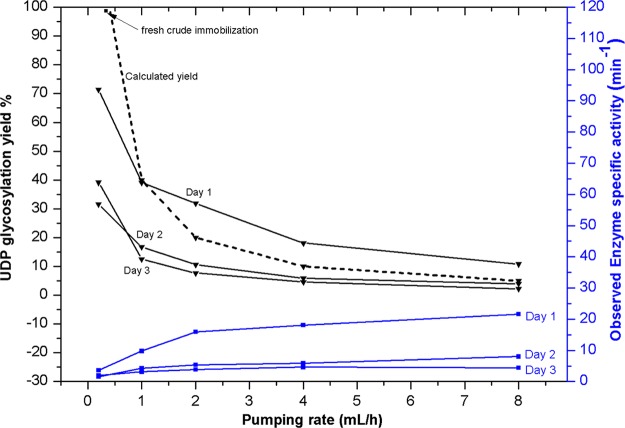

For the current model system, the kinetics of the solid-phase system can be estimated based upon enzyme loading per surface area (i.e., concentration) and flow rates. Specifically, the loading of OleD Loki on the nanometer-scale electrode was 30 μg, giving a local concentration of about 3 g/mL based on the pore volume of the solution adjacent to the 20 nm thick gold electrode. Using the average turnover number of OleD Loki (10 min–1),31,33,34 the theoretical calculated UDP-Glc yield versus flow rate (Figure 5) predicts 0.4 mL/h as the optimal flow rate for continuous UDP-Glc production. Consistent with this model, Figure 5 illustrates the impact of flow rate upon UDP-Glc formation with a maximum yield observed experimentally at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/h. This is also consistent with a model wherein unwanted hydrolysis, which occurs under very high enzyme concentrations in the solution phase over extended periods, does not significantly impact product formation under optimal solid-phase conditions. Specifically, nearly quantitative UDP-Glc formation (98%, square marker shown in Figure 5) was observed experimentally at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/h, illustrating the potential of the immobilized system to reduce unwanted side reactions and thereby optimize product output.

Figure 5.

Calculated (dotted line) and observed UDP-Glc production as a function of flow rate; for a pumping rate of 0.2, 1, and 2 mL/h, the pumping time was 4 h, and for a pumping rate 4 and 8 mL/h, the pumping time was 1 h. Day 1 refers to a complete series of runs at specified pumping rates, followed by repeating a second complete series on day 2 to show enzyme stability. Square marker was for an experiment performed at optimal flow rates with fresh enzyme separated directly from cell crude.

Continuous production is another important merit of an immobilized platform. As part of the study illustrated in Figure 5, a total volume of 84.4 mL of substrate solution was processed using 30 μg of Loki immobilized on the membrane with a total production of 10 μmol UDP-Glc. Using optimal solution-phase conditions (0.5–2 μg/mL), the same reaction volume would require up to 5-fold more enzyme and, if incubated for the same time frame, is expected to suffer a significant reduction in yield due to product hydrolysis. In this particular case, the membrane flow reactor gave a 280-fold improvement in enzyme utilization compared to 0.2 mL of the homogeneous solution protocol with 20 μg of Loki for a total of 2.4 × 10–8 mol UDP-Glc.

Two-step sequential reactions on the membrane-immobilized enzyme system were then carried out to mimic multienzyme processes and compare their performance to solution-based single-glycosyltransferase-coupled reactions. We selected two model GTs (GtfE and OleD Loki) that catalyze glucosyltransfer from UDP-Glc to model acceptors [vancomycin aglycon and 4-methylumbelliferone (4Me-UMB), respectively] with differing proficiencies. Specifically, the turnover rates for GtfE42 and Loki34 are 0.005 and 10 min–1. For the sequential reaction platform, the reaction sequence was physically separated into two discrete steps with the first (UDP-Glc formation, reaction 1) occurring on the top face of the membrane (entry) and the second (aglycon glucosylation, reaction 2) on the bottom face (exit). To afford this physical separation of reactions, the required reagents for reaction 2 were introduced by cross-flow to the bottom surface, as illustrated in Figure 6. This format allows for sequential transfer of intermediates by having separate reagents flowing through the top and supplied orthogonally to the bottom of the membrane. Thus, for the kinetically matched pairing where both GT1 and GT2 (Figure 3) are OleD Loki, the UDP-Glc formed in reaction 1 enters the reaction 2 sequence via directional flow wherein the acceptor 4Me-UMB is only present in the lower reaction vessel at the membrane exit.

Figure 6.

Configuration for the solid-phase two-step sequential reaction process (Figure 3 reaction 1, top face; reaction 2, bottom face) catalyzed by AAO membrane-immobilized OleD Loki. Reaction 1 is carried out on the top membrane entrance to produce UDP-Glc, which is then directed to the bottom membrane exit for the glycosylation of 4Me-UMB (reaction 2).

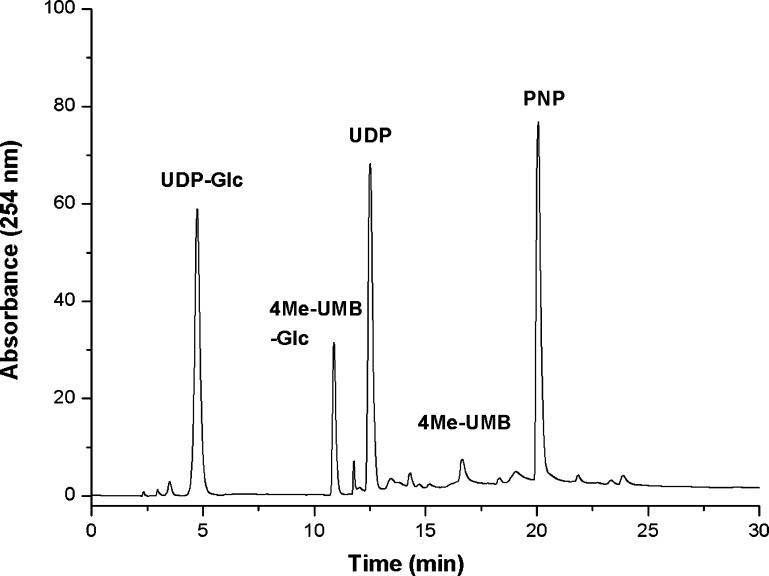

For this analysis, solution-phase and membrane-supported reactions were conducted in parallel using similar conditions to offer a potential comparison of overall utility to afford the desired glycosylated product. For the kinetically matched pairing where both GT1 and GT2 (Figure 3) were OleD Loki, the solution-phase reaction contained 2.56 mM PNP-Glc, 1 mM UDP, 0.56 mM 4Me-UMB, and 100 μg/mL OleD Loki variant in a total volume of 200 μL 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) incubated for 12 h at 25 °C. The corresponding immobilized system employed the same reagents/concentrations where PNP-Glc and UDP were introduced from the top of the membrane using a syringe pump (reaction 1) while 4Me-UMB was separately fed across the bottom of the membrane in orthogonal cross-flow using a second syringe pump (Figure S1), both at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/h. Product formation in the solution-phase reaction and the eluent from the bottom solid-phase reactor face were analyzed by HPLC.

Figure 7 highlights the distribution of reactants/products in the lower eluent of the solid-phase OleD Loki-based sequential reaction series revealing a 71% yield of the desired product (4Me-UMB glucoside). The corresponding solution-phase yield of 4Me-UMB was 16% (Figure S4) wherein potential GT-catalyzed reaction reversibility and UDP-Glc hydrolysis under longer reaction times are likely major contributors to the reduction of the overall yield. While this supports our initial premise that the membrane-immobilized format serves as a potential platform for mimicking Nature’s control of multienzyme sequential reactions, one limitation derives from a need to pair the corresponding enzyme catalytic efficiencies with flow rates. Consistent with this, while a solution-phase sequential OleD/GtfE-catalyzed reaction was previously demonstrated,28 the kinetically mismatched (10 min–1vs 0.005 min–1) OleD Loki (top)/GtfE (bottom) pair failed to afford the final desired product potentially due to an inability to reduce the flow rate to sufficiently compensate for the slow turnover rate of GtfE without succumbing to back diffusion and unwanted OleD Loki-catalyzed hydrolysis of UDP-Glc (Figure S9). In such cases, a possible solution may be to increase the active path length (membrane/electrode thickness) to increase residence time or increase enzyme loading of the slower enzyme.

Figure 7.

HPLC analysis of a representative immobilized sequential reaction containing 2.56 mM PNP-Glc and 1 mM UDP in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, in the upper reactant chamber injected through the membrane carrying immobilized OleD Loki on the top and bottom face into a bottom reaction chamber containing 0.56 mM 4Me-UMB in the same buffer. Flow rate for this sequential reaction was 0.5 mL/h at 25 °C for 4 h, and the bottom reaction chamber contents were subsequently analyzed by HPLC. For comparison, Figure S4 highlights a representative solution-phase sequential reaction.

The design of the membrane platform presented suggests that, like a standard nickel nitrilotriacetic acid resin-based column, this membrane should be able to “capture” active enzyme directly from crude lysates, thereby circumventing the need for protein purification as part of membrane preparation. To assess this, membrane was exposed to 5 mL of crude lysate from a standard OleD Loki E. coli heterologous overproduction culture for 24 h, subsequently washed with Tris-HCl buffer three times, and the purity of the captured protein upon release via treatment with 500 mM imidazole in Tris-HCl buffer solution was determined via SDS-PAGE (Figure S5), which revealed captured protein with a purity of ≥99% (Figure S6). Importantly, the membrane loaded via the crude extract capture method catalyzed nearly quantitative single-step UDP glycosylation (98%) and a corresponding notable two-step 4Me-UMB glycosylation yield (80%) at optimal volume flow rates (Figure S7 and Figure S8).

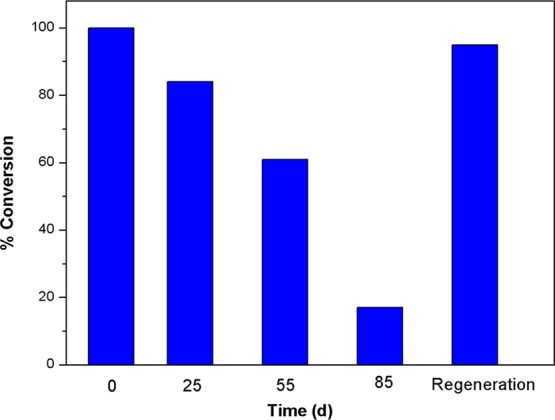

Finally, the membrane-immobilized enzyme also displayed notable stability even after 2 months of cold storage at 4 °C. Specifically, the immobilized enzyme T1/2 based upon UDP-Glc formation was more than 55 days (Figure 8). In addition, the membrane platform is robust and could be reused multiple times via a simple regeneration process (removal of protein with 500 mM imidazole, rinsing with Tris-HCl buffer, and subsequent protein reloading).

Figure 8.

Stability of immobilized enzyme stored at 4 °C where percent conversion is based upon UDP-Glc formation (reaction 1) as determined via HPLC. Regeneration was carried out after 85 days storage of immobilized enzyme at 4 °C.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a design for a robust sequential enzyme reaction system immobilized on nanoscale electrodes at the entrance and exit of AAO membranes. The local enzyme concentration at the nanoscale electrodes is much higher compared to homogeneous solution and allows precise control of the enzyme residence time of substrates, translating to improvements in overall output via the reduction of unwanted side reactions (hydrolysis) and/or potential product inhibitors. Model sequential reactions using the same format revealed similar advantages wherein a main limitation stems from the need to pair enzymes of similar catalytic efficiencies with overall flow rate. In situations where catalytic efficiencies of catalysts dramatically differ, it is expected that extending the path length (i.e., surface area) for slower catalysts could enable pairing with faster catalytic partners. Additional advantages observed in this study include the ability to rapidly capture target catalysts from crude E. coli lysates and the relatively long-term stability of target catalysts and corresponding membrane architecture. As such, this membrane platform offers an opportunity to expand the study and biocatalytic utility of multienzyme cascades with directed mass transport.

Experimental Section

Materials

AAO membranes were purchased from Whatman. Gold(I) thiosulfate was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA), and ascorbic acid was purchased from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ). Vancomycin aglycon31,33 and 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl glucoside31 were prepared as previously reported. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI), and all chemicals were used as received unless otherwise noted. Swinnex 47 mm filter holders were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Membrane/Electrode Fabrication

Sputtering was performed with a Cressington Coating System (Ted-Pella) with calibrated quartz crystal monitor with background pressure of 0.02 mbar. No intermediate wetting layer (i.e., Ti/TiO2) on Al2O3 was needed for seeding the Au layer. Gold (5 nm) was sputtered on the top and bottom of the AAO membranes followed by electroless plating. Electroless plating36 was performed in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1.6 mM sodium gold(I) thiosulfate and 2.68 mM ascorbic acid. The oxidization and reduction reactions were given by

Pore size before and after electroless plating was analyzed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Hitachi S-4300 scanning electron microscope.

Enzyme Immobilization and Regeneration

N-[Nα,Nα-Bis(carboxymethyl)-l-lysine]-12-mercaptododecanamide (NTA) self-assembled monolayer37 was prepared by incubation of gold with 10 mL of 1 mM NTA ethanol solution at 25 °C for 24 h followed by rinsing with 10 mL of ethanol for 3 min and drying under a N2 stream. The membrane was incubated with 10 mL of 0.5 M NiCl2 aqueous solution for 24 h at 25 °C followed by rinsing with 10 mL of Milli-Q water for 3 min and dried under a N2 stream. The production and purification of OleD Loki34 and GtfE42 followed previously reported methods. One side or both sides of the membranes were incubated with an excess of purified enzyme in 10 mL of 50 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) buffer, pH 8.5, for 24 h at 4 °C and washed three times with an equal volume of buffer to remove unbound protein prior to use. Immobilized protein was released by 500 mM imidazole (10 mL, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5) followed by filtering to remove imidazole. The amount of released protein was determined via standard Bradford assay. The OleD Loki-loaded membrane can be regenerated by simply soaking in 500 mM imidazole solution to remove the bound protein, rinsing with Tris-HCl buffer, and subsequent protein reloading.

Protein Capture from E. coli Lysates

Following standard protocol,34 cell pellets from standard heterologous overproduction of OleD Loki in E. coli were collected by centrifugation (6000 g at 4 °C for 20 min), resuspended in 2.5 mL of chilled lysis buffer (20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), and lysed by sonication (5 pulses of 1 min each) in an ice bath. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10 000 g at 4 °C for 20 min), and NTA-Ni-modified membranes were then incubated in the resulting crude extracts (10 mL) for 24 h at 4 °C; the membranes were subsequently washed with 5 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, three times to remove unbound protein.

HPLC Analysis

HPLC was conducted with an Agilent 1260 system equipped with a DAD detector with a 250 mm × 4.6 mm Gemini-NX 5μ C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and using a linear gradient [1% B to 71% B over 30 min, 71% B for 5 min, 71% B to 1% B over 1 min, 1% B for 4 min (solvent A = 50 mM PO42–, 5 mM tetrabutylammonium bisulfate, 2% acetonitrile, pH 6.0; solvent B = acetonitrile); flow rate = 1 mL min–1; A254]. HPLC peak areas were integrated with an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) 1260 workstation, and the percent conversion was calculated based upon peak area of the products and unreacted starting materials. For all reactions, 30 μL aliquots were quenched with an equal volume of MeOH and analyzed via HPLC.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Nanoscale Science and Engineering for critical infrastructure. This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01 DA018822 (to B.J.H.) and R37 AI52218 (to J.S.T.) and DARPA grant W911NF-09-0267 (to B.J.H), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117), the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy and the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center.

Author Present Address

§ Glycom A/S, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark.

Author Present Address

⊥ Department of Materials Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-2120, United States.

Supporting Information Available

Membrane-based sequential reaction setup, enzyme-induced hydrolysis reactions, HPLC of solution-phase sequential reactions, SDS-PAGE of Loki released from AAO membrane, HPLC of enzymatic reactions using membrane-supported enzyme prepared via crude extract capture method, OleD Loki/GtfE sequential reaction scheme. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Riva S. Laccases: Blue Enzymes for Green Chemistry. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meynial S. I.; Forchhammer N.; Croux C.; Girbal L.; Soucaille P. Evolution of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Metabolic Pathway in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2007, 9, 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrado R. J.; Varner J. D.; DeLisa M. P. Engineering the Spatial Organization of Metabolic Enzymes: Mimicking Nature’s Synergy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Du J.; Yan M.; Lao M. Y.; Hu J.; Han H.; Yang O. O.; Liang S.; Wei W.; Wang H.; et al. Biomimetic Enzyme Nanocomplexes and Their Use as Antidotes and Preventive Measures for Alcohol Intoxication. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffelen S.; Hest J. C. M. Multi-enzyme Systems: Bringing Enzymes Together in Vitro. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen C.; Morant M.; Olsen C. E.; Ekstrom C. T.; Galbraith D. W.; Moller B. L.; Bak S. Metabolic Engineering of Dhurrin in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants with Marginal Inadvertent Effects on the Metabolome and Transcriptome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 1779–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierobe H. P.; Bayer E. A.; Tardif C.; Czjzek M.; Mechaly A.; Bélaïch A.; Lamed R.; Shoham Y.; Bélaïch J. P. Degradation of Cellulose Substrates by Cellulosome Chimeras. Substrate Targeting versus Proximity of Enzyme Components. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 49621–49630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh F. G.; Pahan K.; Khan M.; Barbosa E.; Singh I. Abnormality in Catalase Import into Peroxisomes Leads to Severe Neurological Disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 2961–2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodenko B. N.; Westerhoff H. V.; Cascante M. Effect of Channelling on the Concentration of Bulk-Phase Intermediates as Cytosolic Proteins Become More Concentrated. Biochem. J. 1996, 313, 921–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego F. L.; Dannert C. S. Multi-enzymatic Synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbach K.; Mattiasson B. Matrix-Bound Enzymes. Part II: Studies on a Matrix-Bound Two-Enzyme-System. Acta Chem. Scand. 1970, 24, 2093–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo C.; Chmura A.; Rustler S.; Rantwijk F. V.; Stolz A.; Sheldon R. A. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure (S)-Mandelic Acid Using an Oxynitrilase–Nitrilase Bienzymatic Cascade: A Nitrilase Surprisingly Shows Nitrile Hydratase Activity. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Srere P. A.; Mattiasson B.; Mosbach K. An immobilized Three-Enzyme System: A Model for Microenvironmental Compartmentation in Mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1973, 70, 2534–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft O.; Prevot M.; Mohwald H.; Sukhorukov G. B. Shell-in-Shell Microcapsules: A Novel Tool for Integrated, Spatially Confined Enzymatic Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5605–5608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan T. C.; Clark D. S.; Stachowiak T. B.; Svec F.; Frechet J. M. Photopatterning Enzymes on Polymer Monoliths in Microfluidic Devices for Steady-State Kinetic Analysis and Spatially Separated Multi-enzyme Reactions. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 6592–6598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Fang J.; Zhang J.; Liu Z.; Shao J.; Kowal P.; Andreana P.; Wang P. G. Sugar Nucleotide Regeneration Beads (Superbeads): A Versatile Tool for the Practical Synthesis of Oligosaccharides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 2081–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahalka J.; Liu Z.; Chen X.; Wang P. G. Superbeads: Immobilization in “Sweet” Chemistry. Chem.—Eur. J. 2003, 9, 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onda M.; Lvov Y.; Ariga K.; Kunitake T. Sequential Actions of Glucose Oxidase and Peroxidase in Molecular Films Assembled by Layer-by-Layer Alternate Adsorption. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996, 51, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. R.; Datta S.; Gui M.; Coker E. L.; Huggins F. E.; Daunert S.; Bachas L.; Bhattacharyya D. Reactive Nanostructured Membranes for Water Purification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 8577–8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanvir S.; Pantigny J.; Bounois P.; Pulvin S. Covalent Immobilization of Recombinant Human Cytochrome CYP2E1 and Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase in Alumina Membrane for Drug Screening Applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 329, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira G. B.; Filho J. L. L.; Chaves M. E. C.; Azevedo W. M.; Carvalho L. B. Enzyme Immobilization on Anodic Aluminum Oxide/Polyethyleneimine or Polyaniline Composites. React. Funct. Polym. 2008, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Milka P.; Krest I.; Keusgen M. Immobilization of Alliinase on Porous Aluminum Oxide. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2000, 69, 344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara T. D.; Mey I.; Steinem C.; Janshoff A. Benefits and Limitations of Porous Substrates as Biosensors for Protein Adsorption. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 5624–5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan M.; Kramer C.; Steinem C.; Janshoff A. Binding Assay for Low Molecular Weight Analytes Based on Reflectometry of Absorbing Molecules in Porous Substrates. Analyst 2014, 139, 1987–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhathathreyan A. Real-Time Monitoring of Invertase Activity Immobilized in Nanoporous Aluminum Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 6678–6682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirage K. B.; Hulteen J. C.; Martin C. R. Nanotubule-Based Molecular-Filtration Membranes. Science 1997, 278, 655–658. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S.; Lee S. B.; Kang M.; Martin C. R. Size-Based Protein Separations in Poly(ethylene glycol)-Derivatized Gold Nanotubule Membranes. Nano Lett. 2001, 1, 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Griffith B. R.; Fu Q.; Albermann C.; Fu X.; Lee I. K.; Li L.; Thorson J. S. Exploiting the Reversibility of Natural Product Glycosyltransferase-Catalyzed Reactions. Science 2006, 313, 1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Albermann C.; Fu X.; Thorson J. S. The In Vitro Characterization of the Iterative Avermectin Glycosyltransferase AveBI Reveals Reaction Reversibility and Sugar Nucleotide Flexibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16420–16421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Fu Q.; Albermann C.; Li L.; Thorson J. S. The In Vitro Characterization of the Erythronolide Mycarosyltransferase EryBV and Its Utility in Macrolide Diversification. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Cournoyer W. J.; Thorson J. S. Using Simple Donors To Drive the Equilibria of Glycosyltransferase-Catalyzed Reactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Cournoyer W. J.; Thorson J. S. Enzymatic Methods for Glyco(diversification/randomization) of Drugs and Small Molecules. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1811–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier-Pain P.; Marchillo K.; Zhou M.; Andes D. R.; Thorson J. S. Natural Product Disaccharide Engineering through Tandem Glycosyltransferase Catalysis Reversibility and Neoglycosylation. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5086–5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt R. W.; Peltier-Pain P.; Singh S.; Zhou M.; Thorson J. S. Broadening the Scope of Glycosyltransferase-Catalyzed Sugar Nucleotide Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 7648–7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal G. B.; Bamdad C.; Barberis A.; Strominger J.; Whitesides G. M. A Self-Assembled Monolayer for the Binding and Study of Histidine-Tagged Proteins by Surface Plasmon Resonance. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam P.; Kumar K.; Winek G.; Przybycien T. M. Electroless Gold Plating of 316 L Stainless Steel Beads. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 2517–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Bao J.; Chen W.; Liu T.; Zhu Y.; Jin P.; Wang L.; Liu J.; Wei Y.; Li Y. Bifunctional Au-Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Protein Separation. ACS Nano 2007, 1, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Chen T.; Sun X.; Hinds B. J. Dynamic Electrochemical Membranes for Continuous Affinity Protein Separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 4317–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam D. N.; Roberts S.; Proctor M. R.; Turkenburg J. P.; Dodson E. J.; Martinez-Fleites C.; Yang M.; Davis B. G.; Davies G. J. The Crystal Structure of Two Macrolide Glycosyltransferases Provides a Blueprint for Host Cell Antibiotic Immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 5336–5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins J. B.; Onwueme K. C.; Thorson J. S. The Mechanism of CalC: Resistance to Enediyne Antitumor Antibiotics by Self-Sacrifice. Science 2003, 301, 1537–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Hager M. H.; Zhang C.; Griffith B. R.; Lee M. S.; Hallenga K.; Markley J. L.; Thorson J. S. Structural Insight into the Self-Sacrifice Mechanism of Enediyne Resistance. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losey H. C.; Jiang J.; Biggins J. B.; Oberthür M.; Ye X. Y.; Dong S. D.; Kahne D.; Thorson J. S.; Walsh C. T. Incorporation of Glucose Analogs by GtfE and GtfD from the Vancomycin Biosynthetic Pathway to Generate Variant Glycopeptides. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 1305–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.