Abstract

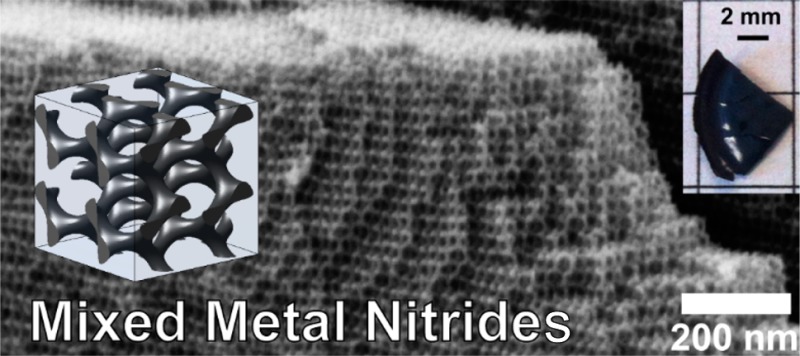

Mesoporous transition metal nitrides are interesting materials for energy conversion and storage applications due to their conductivity and durability. We present ordered mixed titanium–niobium (8:2, 1:1) nitrides with gyroidal network structures synthesized from triblock terpolymer structure-directed mixed oxides. The materials retain both macroscopic integrity and mesoscale ordering despite heat treatment up to 600 °C, without a rigid carbon framework as a support. Furthermore, the gyroidal lattice parameters were varied by changing polymer molar mass. This synthesis strategy may prove useful in generating a variety of monolithic ordered mesoporous mixed oxides and nitrides for electrode and catalyst materials.

Keywords: mesoporous materials, transition metal nitrides, block copolymer gyroid, triblock terpolymer

Transition metal nitride materials are interesting for a host of applications due to their hardness, thermal/electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and catalytic properties.1−4 Furthermore, mixed nitrides often have a combination of useful properties derived from their component nitrides, such as thermal stability and conductivity.3−5 Transition metal nitrides have been investigated as both catalyst and catalyst support materials in different energy devices, including dye-sensitized solar cells,6−9 fuel cells,10−14 and batteries.15 For these energy applications, there is a particular interest in controlled synthetic approaches for monolithic structures that provide three-dimensional (3D) porosity and connectivity with high surface areas and accessibility for the diffusion of fuel, electrolyte, and waste products.16,17

Previous work has shown the ability to convert porous doped and mixed oxides into their corresponding metal nitrides from inverse opal18 or dealloyed oxide materials,19 by heating under flowing ammonia (NH3) gas. The resulting transition metal nitrides exhibited orders of magnitude higher conductivities than their respective oxides.18 These materials were either periodically ordered and macroporous or disordered and mesoporous but not both periodically ordered and mesoporous. Furthermore, none of these materials resulted in monoliths.

Gyroid structures typically comprise two interpenetrating networks structurally related by an inversion operation and separated by a continuous matrix, thus fulfilling the aforementioned structural criteria. In a double gyroid structure, these two networks are composed of the same material, whereas in an alternating gyroid (GA), they are different materials.20 In triblock terpolymer GA structures, the two networks are made of the two different polymer end blocks while the middle block makes up the matrix separating these networks. If everything but one network in the GA structure is removed, as in this work, the resulting structure is a chiral single gyroidal 3D network.21

Block copolymer (BCP) self-assembly has been extensively used for soft templating or structure direction of ordered mesoporous transition metal oxides.22−28 This approach can generate ordered 3D continuous inorganic structures.25 The sole report of a BCP-templated transition metal nitride from an oxide was titanium nitride that was neither a freestanding monolith nor a highly porous 3D continuous network structure.8 Furthermore, the retention of a rigid carbon scaffold was required to prevent mesostructural collapse during polymer removal and nitride crystallization.8 Retaining the carbon scaffold may not be ideal in energy systems like PEMFCs11 and Li–O2 batteries.29 We report monolithic gyroidal mesoporous mixed transition metal nitrides. These mesoporous crystalline materials maintain a high degree of both macroscopic integrity and mesoscale order that have not been previously observed for BCP-templated inorganic structures; all of this is accomplished without a rigid carbon support.

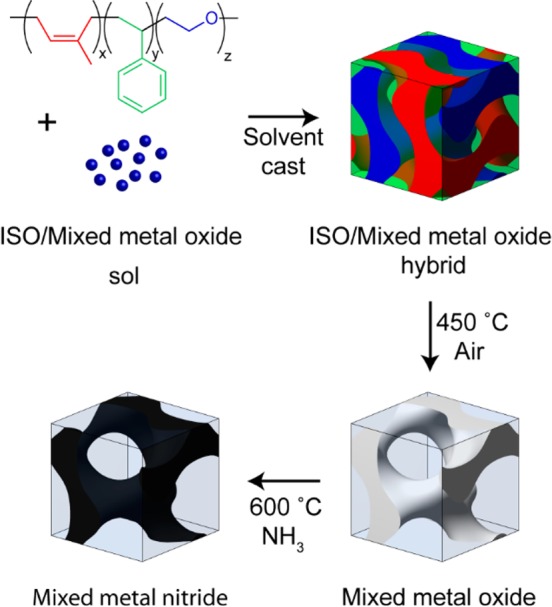

In the current work, BCP-templated monolithic 3D networked mixed metal oxides (Ti1-xNbxO2) were converted to monolithic 3D networked mixed metal nitrides (Ti1-xNbxO2) by heating under flowing NH3 gas. The Ti:Nb molar ratios in the oxide sol were 8:2 or 1:1. The 8:2 ratio was chosen because Nb can be incorporated into anatase TiO2 at and above this composition.30 The 1:1 composition was chosen because we have previously investigated mesoporous Ti0.5Nb0.5N as a catalyst support for oxygen reduction.31 Ti1-xNbxO2 is also a known transparent conducting oxide with various mesoporous morphologies and applications studied.30,32 As detailed in the Methods section, the BCP/oxide hybrids are prepared by the coassembly of triblock terpolymers and sol–gel-derived precursors.25 The poly(isoprene-block-styrene-block-ethylene oxide) triblock terpolymers are referred to as ISO1, ISO2, and ISO3. Polymer ISO1 had a molar mass of 59 600 g mol–1 and comprised 29.7, 62.8, and 7.5 wt % polyisoprene (I), polystyrene (S), and poly(ethylene oxide) (O), respectively, with a polydispersity index of 1.09. Polymer ISO2 had a molar mass of 69 000 g mol–1 and comprised 29.6, 64.8, and 5.6 wt % I, S, and O, respectively, with a polydispersity index of 1.04. Polymer ISO3 had a molar mass of 63 800 g mol–1 and comprised 29.3, 63.6, and 7.1 wt % I, S, and O, respectively, with a polydispersity index of 1.03. The amphiphilic triblock terpolymers, ISO1, ISO2, or ISO3, are dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and mixed with an aliquot of the hydrophilic oxide sols. Hybrids from ISO1, ISO2, and ISO3 self-assemble into ordered morphologies upon solvent evaporation, a process now referred to as evaporation-induced self-assembly.26,33 The hydrophilic metal oxide sol selectively swells the hydrophilic poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) block of the BCP. The hydroxyl groups of the oxide sol hydrogen bond to oxygen atoms in the PEO chains. As the solvent is evaporated from the system during film casting, the polymer blocks phase separate on the mesoscale to minimize the interfacial surface area between the blocks, which leads to ordered morphologies.16 In this work, the PEO block incorporates the metal oxide sol which comprises one network of the alternating gyroid structure after solvent evaporation, shown as the blue network in Figure 1. Calcination in air at 450 °C removes the BCP templates, sintering the inorganic sol particles, leaving freestanding monolithic mesoporous oxides with a 3D ordered continuous network morphology as shown as the white network in Figure 1. These oxides can then be converted to monolithic nitrides with a subsequent heat treatment at 600 °C under flowing ammonia shown as the black network in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the process for the generation of ordered mesoporous metal nitride monoliths.

Results and Discussion

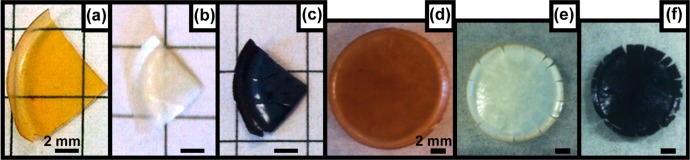

Interestingly, as the polymer templates are removed at 450 °C in air, the oxides maintain their macrostructure, despite major shrinkage. In Figure 2, the width of the as-made ISO2 Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid sample (a) is 8.7 mm, and the width after conversion to an oxide (b) is 6.8 mm, a difference of 22%. In contrast, there is little change in the width between the oxide (b) and resulting nitride sample (c). In Figure 2, the width of the as-made ISO3 Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 hybrid sample (d) is 14.3 mm, and the width after conversion to an oxide (e) is 11.2 mm, a difference of 22%. After the nitriding process (f), the sample width is 10.1 mm, a difference of 10%. The oxides are translucent white, consistent with the removal of polymeric material under these calcination conditions.25 Furthermore, the materials retain their macrostructure after the nitriding process at 600 °C. The resulting monolithic materials are black (c,f), consistent with metal center reduction, yielding the nitrides.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the freestanding monolithic materials throughout processing. (a) ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid, (b) Ti0.8Nb0.2O2, and (c) Ti0.8Nb0.2N; (d) ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 hybrid, (e) Ti0.5Nb0.5O2, and (f) Ti0.5Nb0.5N.

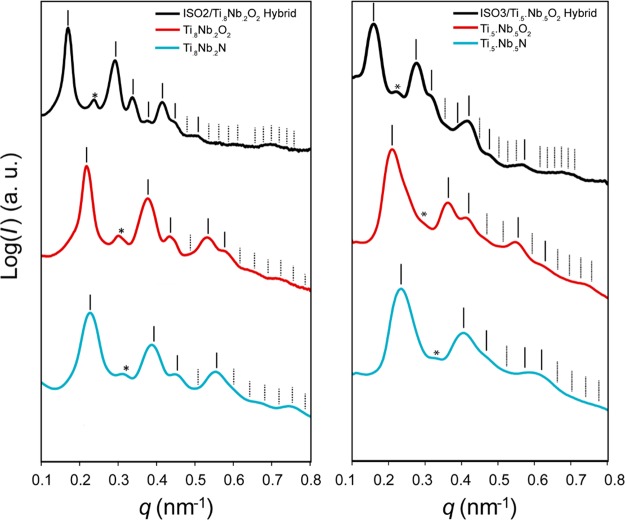

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was used to measure the mesoscale order of the various ISO1- ISO2- and ISO3-derived samples. The left of Figure 3 shows the results for the ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 system (for SAXS of ISO1/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2, see Supporting Information Figure S1): ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid (left, top), freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 (left, middle), and freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2N (left, bottom). The two-dimensional experimental patterns taken with incident X-rays parallel to the film normal (z-direction) were azimuthally integrated to yield the one-dimensional patterns shown in the figures. These patterns are consistent with the GA morphology, except for a forbidden peak at (q/q100)2 = 4. This peak is attributed to symmetry breaking from z-direction compression during solvent evaporation (see Figure S2). This phenomenon has been studied previously in similar BCP/oxide systems.25,34 A systematic shift of the (q/q100)2 = 6 peak compared to (q/q100)2 = 2 and (q/q100)2 = 8 in the nitride is also observed in some samples (see also Figure S1). This shift may be due to anisotropic shrinkage of the mesostructure during processing.34 As the sample progresses from a hybrid, to a freestanding oxide, to a freestanding nitride, all peaks shift to higher q values and tend to broaden. The shift to higher q values correlates to decreases in d100 spacings (52.4, 40.7, and 39.1 nm for the hybrid, oxide, and nitride, respectively). The hybrid to oxide d100 spacing shrinkage of 22% is consistent with the 22% macroscopic shrinkage observed upon polymer removal, as seen in Figure 2. The smaller 4% d100 spacing shrinkage between the oxide and nitride is consistent with macroscopic size retention. The SAXS patterns of the ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 system (shown in Figure 3, right) display trends similar to those of the ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 system: shifting to higher q values and broadening of peaks throughout the processing. The shift to higher q values correlates to decreases in d100 spacings (55.9, 42.3, and 37.9 nm for the hybrid, oxide, and nitride, respectively). For ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2, the hybrid to oxide d100 spacing shrinkage of 24% is consistent with the 22% macroscopic shrinkage observed upon polymer removal, as seen in Figure 2. The smaller 10% d100 spacing shrinkage between the oxide and nitride is also consistent with macroscopic shrinkage of 10%. Remarkably, as indicated by the SAXS patterns, the materials maintain significant long-range mesoscale order, despite a total d100 spacing shrinkage of over 25% and heat treatments as high as 600 °C. The d100 spacings of all ISO terpolymer-derived materials, including ISO1-derived films (see Supporting Information), are summarized in Table S2 and demonstrate tailoring of cubic lattice parameters by polymer molar mass and BCP/sol composition.

Figure 3.

Azimuthally integrated small-angle X-ray scattering patterns of the ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid (left, top), calcined freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 (left, middle), and freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2N (left, bottom); ISO3/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid (right, top), calcined freestanding Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 (right, middle), and freestanding Ti0.5Nb0.5N (right, bottom). The vertical lines indicate expected peak positions for the GA morphology. Dotted lines represent unobserved GA peaks, and asterisks are centered at forbidden (q/q100)2 = 4 peak positions that appear due to z-direction compression.

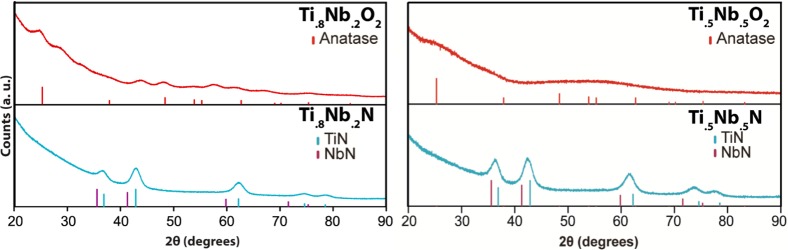

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed on the calcined and nitrided samples from an ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 hybrid, as shown in Figure 4 (left) and from an ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 hybrid, as shown in Figure 4 (right). The ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 oxide sample calcined at 450 °C in air shows very broad peaks consistent with very small crystallites and predominantly amorphous content (Figure 4, top left). Under these calcination conditions, pure titania is crystalline anatase and pure niobia remains fully amorphous.35 It is known, however, that introducing dopant atoms such as Nb delays the onset of crystallization and anatase-to-rutile transformations in titania.30,32 Some of the weak peaks in the observed oxide pattern match expected anatase TiO2 peaks, but several others do not index with anatase TiO2, rutile TiO2, or T-Nb2O5 and may indicate a mixed composition. The broad peaks with low intensity make definitive microphase identification of the composite material difficult. The corresponding nitrided sample (Figure 4, bottom left) shows an XRD pattern exhibiting peaks consistent with the rock salt structure and intensities consistent with a TiN-rich phase. There appears to be no crystalline oxide present. The crystallite size for the nitride, as calculated by the Scherrer equation, is approximately 4.7 nm, roughly half the diameter of a network strut as seen in SEM (see below). Due to the broadness of the peaks and similar lattice parameters, it is difficult to definitively distinguish between a single phase of Ti0.8Nb0.2N and a mix of the two nitrides, as well as from any amorphous or oxynitride content. The ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2-derived oxide sample calcined at 450 °C in air only shows amorphous material due to the higher niobia content (Figure 4, top right). The nitrided sample (Figure 4, bottom right) also shows an XRD pattern exhibiting peaks consistent with the rock salt structure, with peak positions and intensities consistent with a mixed TiN–NbN. There appears to be no crystalline oxide present. The crystallite size for the nitride, as calculated by the Scherrer equation, is approximately 4.5 nm, roughly half the diameter of a network strut as seen in SEM (see below).

Figure 4.

Powder XRD patterns of the ordered mesoporous freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 and Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 (top) as well as ordered mesoporous freestanding Ti0.8Nb0.2N and Ti0.5Nb0.5N (bottom) derived from ISO2/Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 and ISO3/Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 hybrids, respectively. The oxide patterns have peak markings with relative intensities for anatase TiO2 (PDF Card 00-001-0562). Unindexed peaks for Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 are likely due to different Ti1-xNbxO2 compositions. The nitrides patterns (bottom) are a cubic rock salt structure, characteristic of many metal nitrides, including TiN and NbN. Peak markings and relative intensities for TiN (blue) (PDF Card 04-015-2441) and NbN (purple) (PDF Card 04-008-5125) are shown.

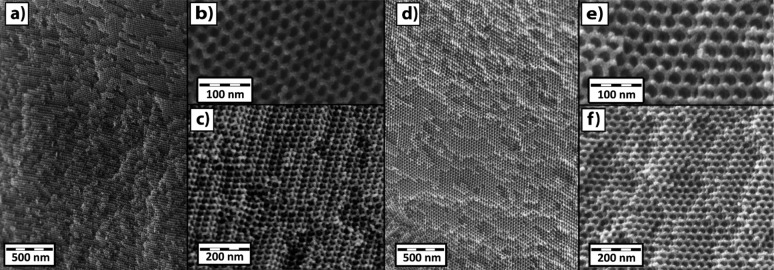

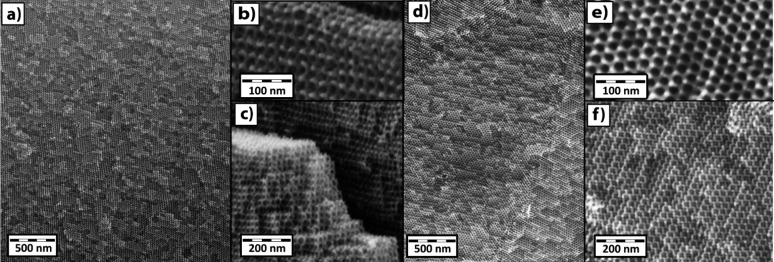

Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Figures 5 and 6), and images in the Supporting Information (Figures S3–S5) show the 3D networks of oxide and nitride samples. The oxide sample required coating with Au–Pd for sufficient conductivity for imaging. In contrast, the nitride SEM samples required no conductive coating, indicating electrical conductivity, as expected. The measured feature sizes in the Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 (Figure 5a–c) sample were strut diameters of about 11 nm with 19 nm pores. For Ti0.8Nb0.2N (Figure 6a–c), the strut diameter, as measured by SEM, is 9 nm, with pores of 15 nm. The measured feature sizes in the Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 sample (Figure 5d–f) were strut diameters of about 11 nm with 21 nm pores. For the Ti0.5Nb0.5N sample (Figure 6d–f), the strut diameter, as measured by SEM, is 9 nm, with pores of 20 nm. While the gyroid structure is the same between the oxides and nitrides (as confirmed by SAXS), the feature sizes are slightly larger for the oxides than in the nitrides, which is consistent with a small difference in SAXS d100 spacings. SEM measurements of the feature sizes are strongly influenced by the projection and orientation of the sample, however, and merely serve as a guide while the SAXS provides a more bulk sampling of the characteristic morphology dimensions. Slight variations between samples may also result in slightly different feature sizes.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional SEM images, at different magnifications, of single domains >1 μm of Au–Pd-coated Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 (a–c) samples made with ISO2 and Ti0.5Nb0.5O2 (d–f) samples made with ISO3. The long-range order of single domains is shown in (a) and (d), while (b), (c), (e), and (f) reveal the three-dimensionality of the cubic GA structures.

Figure 6.

Cross-sectional SEM images, at different magnifications, of single domains >1 μm of uncoated Ti0.8Nb0.2N (a–c) samples made with ISO2 and Ti0.5Nb0.5N (d–f) samples made with ISO3. The long-range order of a single domain is shown in (a), while (b), (c), (e), and (f) reveal the three-dimensionality of the cubic GA structures.

Conductivity measurements on monoliths of the nitrides were performed using a two-point probe setup. Two Ti0.8Nb0.2N monoliths showed an average conductivity of 7.3 S/cm, and two Ti0.5Nb0.5N monoliths showed an average conductivity of 3.5 S/cm. The conductivity calculations did not take into account porosity, which lowers the conductivity of the bulk material. Results of additional conductivity characterization, as well as optical characterization (UV–vis–NIR and Raman spectroscopies) can be found in the Supporting Information, revealing more changes of materials properties when moving from the oxides to the nitrides.

It is particularly interesting that, in contrast to syntheses explored previously, the structure retention occurs in these materials without a carbon scaffold that usually prevents collapse of the structure during calcination or crystallization.8,27 The slow ramp rates of the heating procedures (1–2 °C/min) and the nature of the amorphous matrix containing small crystallites in one case may mitigate the stresses of shrinkage, particularly in the case of the Ti0.8Nb0.2O2 composition. We speculate that the 3D nature of the gyroidal structure and large grain sizes in both compositions may aid mesostructure retention without a hard template.36 Incorporating Nb may prevent macroscopic pulverization by delaying crystallization at the calcination temperature. In addition, the uniform 3D mesoporosity of the structure provides short diffusion lengths on the order of nanometers for the nitriding process, allowing the reaction to occur at 600 °C, mild enough to prevent mesostructure collapse during crystallization.

Conclusions

In summary, by combining self-assembling triblock terpolymers with oxides that are crystalline (titania) and amorphous (niobia) at 450 °C, we generate a mixed oxide, Ti0.8Nb0.2O2, with small oxide crystallites in an amorphous oxide matrix as well as an amorphous mixed oxide, Ti0.5Nb0.5O2. These materials retain their macrostructure and mesostructure extremely well upon heat treatment, compared to the BCP-directed component oxides that have been studied.27 These mesoporous mixed oxides can subsequently be nitrided at 600 °C to generate conductive monolithic ordered mesoporous materials for electrode applications. The retention of both the ordered mesostructure and macrostructure during heat treatments, shrinkage, and crystallization opens new possibilities for ordered mesoporous materials. This strategy may be generalized for generating various BCP-directed, ordered mesoporous mixed transition metal oxides and nitrides.

Methods

Materials

Hydrochloric acid (37 wt %, ACS/NF/FCC, Aristar BDH), titanium(IV) isopropoxide (Aldrich, 97%), niobium(V) ethoxide (Aldrich 99.95%, trace metal basis) (for Ti0.8Nb0.2O2), niobium(V) ethoxide (Alfa-Aesar 99.999%, metals basis, Ta <500 ppm) (for Ti0.5Nb0.5O2), and tetrahydrofuran (Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, ≥99.9%, inhibitor-free) were all used as received.

The block copolymers, poly(isoprene-block-styrene-block-ethylene oxide) (ISO1, ISO2, and ISO3), were synthesized by sequential anionic polymerization. The block copolymer compositions and polydispersity indices were characterized by a combination of size exclusion chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance.

Synthesis of ISO Block Terpolymers

The block terpolymers, poly(isoprene)-block-poly(styrene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide), were synthesized by sequential anionic polymerization techniques which are described in greater detail elsewhere.25,37,38 The poly(isoprene) block was initiated by sec-butyllithium in benzene, to which the isoprene monomer was added. The styrene monomer was added to the living poly(isoprene) to generate poly(isoprene)-block-poly(styrene). The living poly(isoprene)-block-poly(styrene) chains were end-capped with ethylene oxide and terminated with methanolic HCl, yielding −OH-terminated poly(isoprene)-block-poly(styrene). The diblock copolymer was purified using water/chloroform washing and dried on a Schlenk line. The diblock copolymer was then dissolved in tetrahydrofuran and reinitiated with potassium naphthalide. The poly(ethylene oxide) block was grown by the addition of ethylene oxide to the initiated diblock copolymer. Finally, the triblock terpolymer poly(isoprene)-block-poly(styrene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) was terminated with methanolic HCl, purified by washing, and dried on a Schlenk line. We note that sec-butyllithium is a pyrophoric liquid, and ethylene oxide is a highly toxic, flammable gas at room temperature. As such, extreme caution should be used with these reagents! Air- and water-free conditions are necessary for the anionic synthesis.

Synthesis of Monolithic Mesoporous Mixed Nitrides

For Ti0.8Nb0.2O2, 100 mg of either ISO1 or ISO2 was dissolved in 3 mL of anhydrous THF to give a 3.5 wt % solution. The mixed oxide sol was prepared by a hydrolytic route, adapted from a previous publication.25 First, 1 mL (3.4 mmol) of titanium(IV) isopropoxide was quickly added to 0.38 mL of HCl, with vigorous stirring in a 20 mL vial. After 2.5 min, 0.21 mL (0.8 mmol) of niobium(V) ethoxide was quickly added to the stirring vial. After another 2.5 min, 2.5 mL (30.8 mmol) of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran was quickly added. After 2 min, an aliquot of the transparent pale yellow sol was added to the polymer solution. For ISO1 (59.6 kg/mol ISO, 4.5 kg/mol PEO), the sol aliquot was 0.32 mL/100 mg of ISO1 to generate a GA morphology. For ISO2 (69 kg/mol ISO, 3.9 kg/mol PEO), the sol aliquot was 0.34 mL/100 mg of ISO2 to generate a GA morphology, due to its smaller PEO block.

For Ti0.5Nb0.5O2, 75 mg of ISO3 was dissolved in 2 mL of anhydrous THF to give a 4.0 wt % solution. The mixed oxide sol–gel precursor for Ti0.5Nb0.5N was also prepared by a hydrolytic sol–gel route. First, 0.90 mL (3 mmol) of titanium(IV) isopropoxide was added to 0.74 mL (3 mmol) of niobium(V) ethoxide in an inert atmosphere glovebox to give a mixed alkoxide precursor. Second, 0.778 g (∼0.85 mL) of the mixed alkoxide precursor was quickly added to 0.30 mL of HCl and 1 mL of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran, with vigorous stirring in a 4 mL vial. After 5 min, another 1 mL of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran was quickly added to the stirring vial. After 2 min, an aliquot of the transparent yellow sol was added to the polymer solution. The sol aliquot was 0.24 mL/75 mg ISO3 to generate a GA morphology.

The ISO/oxide mixtures were stirred vigorously for at least 3 h. Films were then cast in PTFE dishes. The solvent was evaporated with the PTFE dish on a glass Petri dish covered by a glass dome, on a hot plate set to 50 °C overnight. Films were subsequently aged at 160 °C (Ti0.8Nb0.2O2) or 130 °C (Ti0.5Nb0.5O2) overnight in a vacuum oven. The highly ordered structure was generated through the slow, controlled evaporation of solvent, leading to large gyroidal domain sizes. The aging process does not appear to play a major role in the generation of large domain ordered mesostructures but makes the films more robust and less prone to cracking over time.

Films were calcined in air to generate the freestanding oxide in a flow furnace, 3 h at 450 °C with a ramp rate of 1 °C/min and allowed to cool to ambient conditions.

For nitriding the resulting oxides, the films were heated in a flow furnace under anhydrous ammonia gas at a flow rate of 2.5 L/h for 6 h at 600 °C, with a ramp rate of 1.6 °C/min (about 100 °C/h). The flow tubes were cooled to room temperature under flowing ammonia and then purged with N2. One tube valve was opened to air for 30 min, and then the tube end was removed. Finally, the sample was removed from the tube.

XRD Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction data for powders of the mixed oxide and mixed nitride were collected on a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer equipped with a D/teX Ultra detector, using Cu Kα radiation and a scan rate of 2°/min (Ti0.8Nb0.2O2) or 5°/min (Ti0.5Nb0.5O5).

SAXS Characterization

Small angle X-ray scattering patterns were obtained on a home-built beamline equipped with a Rigaku RU-3HR copper rotating anode generator, a set of orthogonal Franks focusing mirrors, and a phosphor-coupled CCD detector, as described elsewhere.39 Some SAXS patterns were also obtained at the G1 station of the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), with a beam energy of 10.5 keV and sample-to-detector distance of approximately 2.5 m. The two-dimensional patterns obtained from a point-collimated beam were azimuthally integrated to yield the one-dimensional plots shown in Figures 3 and S1.

SEM Characterization

Fractured and powdered oxide monoliths were directly mounted on stubs and coated with Au–Pd. The Au–Pd coating on the oxides causes the surface roughness seen in Figure 5. Fractured and powdered nitride monoliths were directly mounted on stubs using carbon tape without any coating. Samples were characterized by SEM on a Zeiss LEO-1550 FE-SEM instrument and a TESCAN MIRA3 LM FE-SEM instrument using in-lens detectors.

Conductivity Characterization

Conductivity of ISO-derived nitride monoliths were measured by a two-point probe setup. Before calcination, the ISO-derived hybrid films were treated with CF4 plasma to remove any closed overlayers. After calcination and nitriding, monoliths were masked with tape and sputtered with Au–Pd to deposit electrode contacts. On each of these Au–Pd contacts, a drop of liquid metal eutectic Ga/In was placed. The Ga–In eutectic is useful for avoiding direct pressure to the monoliths during measurements which can cause cracking. Resistance measurements were performed across the known cross section of a nitride monolith using a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter. Conductivity values were calculated using the measured resistance and measured sample dimensions of the cross section.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported as part of the Energy Materials Center at Cornell (EMC2), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-SC0001086. This work made use of the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities, which are supported through the NSF MRSEC program (DMR-1120296). This work is based upon research conducted at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), which is supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences under NSF award DMR-0936384. H.S. was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Single Investigator Award (DMR-1104773). S.W.R. acknowledges K.W. Tan for help in acquiring SEM images, and D.T. Moore for help with UV–vis–NIR measurements.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details and additional figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Marchand R.; Laurent Y.; Guyader J.; L’Haridon P.; Verdier P. Nitrides and Oxynitrides: Preparation, Crystal Chemistry and Properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 8, 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama S. T. Preparation and Catalytic Properties of Transition-Metal Carbides and Nitrides. Catal. Today 1992, 15, 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- DiSalvo F. J.; Clarke S. J. Ternary Nitrides: A Rapidly Growing Class of New Materials. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1996, 1, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Niewa R.; DiSalvo F. J. Recent Developments in Nitride Chemistry. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 2733–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Elder S. H.; DiSalvo F. J.; Topor L.; Navrotsky A. Thermodynamics of Ternary Nitride Formation by Ammonolysis: Application to LiMoN2, Na3WN3, and Na3WO3N. Chem. Mater. 1993, 5, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q. W.; Li G. R.; Gao X. P. Highly Ordered TiN Nanotube Arrays as Counter Electrodes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Commun. 2009, 44, 6720–6722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. R.; Wang F.; Jiang Q. W.; Gao X. P.; Shen P. W. Carbon Nanotubes with Titanium Nitride as a Low-Cost Counter-Electrode Material for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3653–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy E.; Jo C.; Anthonysamy A.; Jeong I.; Kim J. K.; Lee J. Soft-Template Simple Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous Titanium Nitride-Carbon Nanocomposite for High Performance Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Counter Electrodes. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Zhang X.; Zhang C.; Liu Z.; Zhou X.; Pang S.; Chen X.; Dong S.; Zhang Z.; Zhang L.; et al. Nanostructured Titanium Nitride/PEDOT:PSS Composite Films as Counter Electrodes of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara A.; Lee K.; Doi S.; Mitsushima S.; Kamiya N.; Hara M.; Domen K.; Fukuda K.; Ota K. Tantalum Oxynitride for a Novel Cathode of PEFC. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2005, 8, A201–A203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H. X.; Zhang H. M.; Liang Y. M.; Zhang J. L.; Wang M. R.; Wang X. L. A Novel Non-noble Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2007, 164, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Avasarala B.; Murray T.; Li W.; Haldar P. Titanium Nitride Nanoparticles Based Electrocatalysts for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 1803–1805. [Google Scholar]

- He P.; Wang Y. G.; Zhou H. S. Titanium Nitride Catalyst Cathode in a Li-Air Fuel Cell with an Acidic Aqueous Solution. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10701–10703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. R.; Ohnishi R. H.; Yoo E.; He P.; Kubota J.; Domen K.; Zhou H. S. Nano- and Micro-Sized TiN as the Electrocatalysts for ORR in Li-Air Fuel Cell with Alkaline Aqueous Electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 15549–15555. [Google Scholar]

- Dong S. M.; Chen X.; Zhang K. J.; Gu L.; Zhang L. X.; Zhou X. H.; Li L. F.; Liu Z. H.; Han P. X.; Xu H. X.; et al. Molybdenum Nitride Based Hybrid Cathode for Rechargeable Lithium–O2 Batteries. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11291–11293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orilall M. C.; Wiesner U. Block Copolymer Based Composition and Morphology Control in Nanostructured Hybrid Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage: Solar Cells, Batteries, and Fuel Cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 520–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcarius A. Mesoporous Materials and Electrochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4098–4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subban C. V.; Smith I. C.; DiSalvo F. J. Interconversion of Inverse Opals of Electrically Conducting Doped Titanium Oxides and Nitrides. Small 2012, 8, 2824–2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; MacLeod M. J.; Tessier F.; DiSalvo F. J.; Klein L. C. Mesoporous Metal Nitride Materials Prepared from Bulk Oxides. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 95, 3084–3089. [Google Scholar]

- Meuler A. J.; Hillmyer M. A.; Bates F. S. Ordered Network Mesostructures in Block Polymer Materials. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7221–7250. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Hur K.; Sai H.; Higuchi T.; Takahara A.; Jinnai H.; Gruner S. M.; Wiesner U. Linking Experiment and Theory for Three-Dimensional Networked Binary Metal Nanoparticles—Triblock Terpolymer Superstructures. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P. D.; Zhao D. Y.; Margolese D. I.; Chmelka B. F.; Stucky G. D. Block Copolymer Templating Syntheses of Mesoporous Metal Oxides with Large Ordering Lengths and Semicrystalline Framework. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 2813–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Smarsly B.; Antonietti M. Block Copolymer Assemblies as Templates for the Generation of Mesoporous Inorganic Materials and Crystalline Films. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 6, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y.; Ma Z.; Bruce P. G. Ordered Mesoporous Metal Oxides: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4909–4927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefik M.; Wang S.; Hovden R.; Sai H.; Tate M. W.; Muller D. A.; Steiner U.; Gruner S. M.; Wiesner U. Networked and Chiral Nanocomposites from ABC Triblock Terpolymer Coassembly with Transition Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Templin M.; Franck A.; DuChesne A.; Leist H.; Zhang Y. M.; Ulrich R.; Schadler V.; Wiesner U. Organically Modified Aluminosilicate Mesostructures from Block Copolymer Phases. Science 1997, 278, 1795–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Orilall M. C.; Warren S. C.; Kamperman M.; DiSalvo F. J.; Wiesner U. Direct Access to Thermally Stable and Highly Crystalline Mesoporous Transition-Metal Oxides with Uniform Pores. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastakoti B. P.; Ishihara S.; Leo S.-Y.; Ariga K.; Wu K. C. W.; Yamauchi Y. Polymeric Micelle Assembly for Preparation of Large-Sized Mesoporous Metal Oxides with Various Compositions. Langmuir 2014, 30, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottakam Thotiyl M. M.; Freunberger S. A.; Peng Z.; Bruce P. G. The Carbon Electrode in Nonaqueous Li–O2 Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dros A. B.; Grosso D.; Boissière C.; Soler-Illia G. J. de A. A.; Albouy P.-A.; Amenitsch H.; Sanchez C. Niobia-Stabilised Anatase TiO2 Highly Porous Mesostructured Thin Films. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 94, 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z.; Burns R. G.; DiSalvo F. J. Mesoporous Ti0.5Nb0.5N Ternary Nitride as a Novel Noncarbon Support for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Acid and Alkaline Electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 3782–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J.; Szeifert J. M.; Feckl J. M.; Mandlmeier B.; Rathousky J.; Hayden O.; Fattakhova-Rohlfing D.; Bein T. Niobium-Doped Titania Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Assembly into Mesoporous Films and Electrical Conductivity. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5373–5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinker C. J.; Lu Y. F.; Sellinger A.; Fan H. Y. Evaporation-Induced Self-Assembly: Nanostructures Made Easy. Adv. Mater. 1999, 11, 579–585. [Google Scholar]

- Toombes G. E. S.; Finnefrock A. C.; Tate M. W.; Ulrich R.; Wiesner U.; Gruner S. M. A Re-evaluation of the Morphology of a Bicontinuous Block Copolymer-Ceramic Material. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 8974–8982. [Google Scholar]

- Orilall M. C.; Abrams N. M.; Lee J.; DiSalvo F. J.; Wiesner U. Highly Crystalline Inverse Opal Transition Metal Oxides via a Combined Assembly of Soft and Hard Chemistries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8882–8883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnefrock A. C.; Ulrich R.; DuChesne A.; Honeker C. C.; Schumacher K.; Unger K. K.; Gruner S. M.; Wiesner U. Metal Oxide Containing Mesoporous Silica with Bicontinuous “Plumber’s Nightmare” Morphology from a Block Copolymer–Hybrid Mesophase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1207–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgaier J.; Poppe A.; Willner L.; Richter D. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly[1,4-isoprene-b-(ethylene oxide)] and Poly[ethylene-co-propylene-b-(ethylene oxide)] Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Warren S. C.; DiSalvo F. J.; Wiesner U. Nanoparticle-Tuned Assembly and Disassembly of Mesostructured Silica Hybrids. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnefrock A. C.; Ulrich R.; Toombes G. E. S.; Gruner S. M.; Wiesner U. The Plumber’s Nightmare: A New Morphology in Block Copolymer–Ceramic Nanocomposites and Mesoporous Aluminosilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13084–13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.