Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a growth factor-like mediator and a ligand for multiple GPCR. The LPA2 GPCR mediates antiapoptotic and mucosal barrier-protective effects in the gut. We synthesized sulfamoyl benzoic acid (SBA) analogues that are the first specific agonists of LPA2, some with subnanomolar activity. We developed an experimental SAR that is supported and rationalized by computational docking analysis of the SBA compounds into the LPA2 ligand-binding pocket.

Introduction

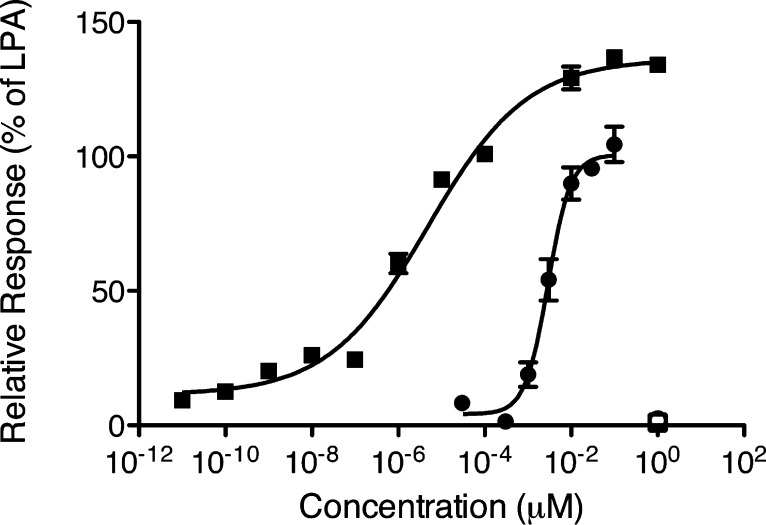

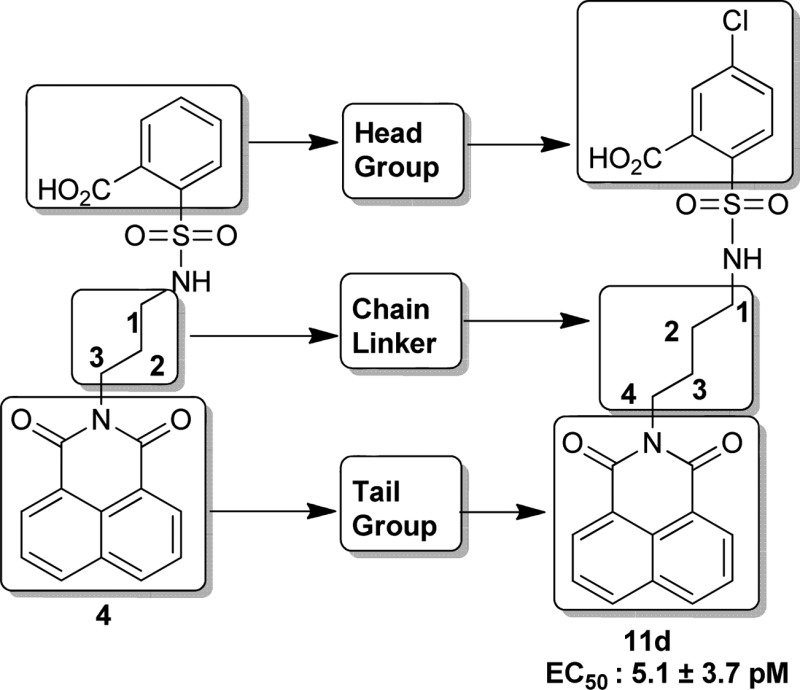

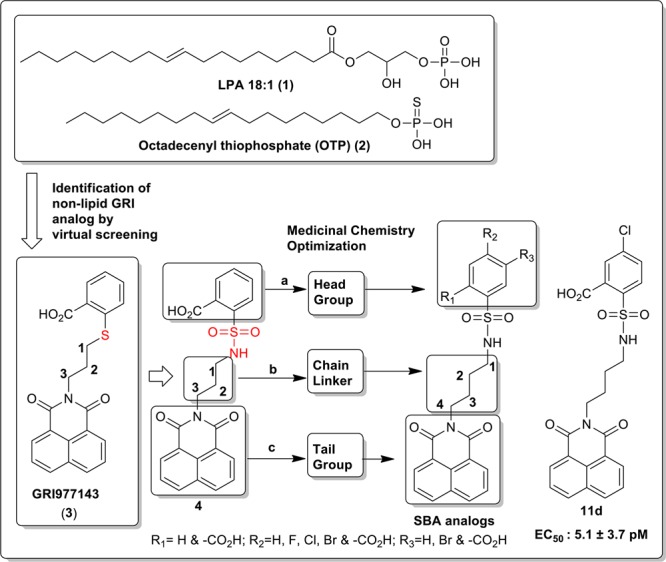

Exposure to direct ionizing radiation can result in programmed cell death due to the accompanying DNA damage. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA, 1-acyl-2-hydroxy-sn-3-glycerophosphate) (1, Figure 1) is a growth factor-like lipid mediator with antiapoptotic actions elicited via a set of G protein coupled receptors. LPA GPCR activate antiapoptotic kinase pathways, inhibit apoptosis, promote cell regeneration, and augment DNA repair, altogether.1−4 Our group has been interested in developing LPA analogues for the attenuation of programmed cell death elicited by radiation and chemotherapeutic agents.2,5−7 In the course of our studies, we discovered octadecenyl thiophosphate (OTP) (2, Figure 1), a synthetic analogue of LPA, which showed strong radioprotective action by rescuing cells from apoptosis and mice irradiated with lethal doses of γ-irradiation.7 Although OTP is highly effective in protecting animals from radiation injury, it activates multiple LPA GPCRs, including LPA1 that has been linked to cause apoptosis via anoikis.8,9 Recently, our group identified novel nonlipid compounds that are selective, although not specific, agonists of LPA2 and also inhibit LPA3.10 Among these nonlipid compounds, GRI977143 (3, Figure 1), although much less potent than LPA, nevertheless showed antiapoptotic efficacy in cell-based models of apoptosis and it was modestly efficacious against radiation-induced apoptosis in mice suffering from the acute hematopoietic radiation syndrome.10 In continuation of this line of research, we designed and synthesized sulfamoyl benzoic acid (SBA) analogues of 3 by isoteric replacement of −S– group with −NH-SO2 using a medicinal chemistry approach guided by computational modeling.11,12 All 14 new SBA analogues were tested for agonist and antagonist activity at the LPA1/2/3/4/5 GPCR. We found several nonlipid specific agonist of LPA2, one of which is 5-chloro-2-(N-(4-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)butyl)sulfamoyl)benzoic acid (11d) (Scheme 4), with picomolar activity (EC50 = 5.06 × 10–3 ± 3.73 × 10–3 nM vs LPA 18:1; EC50 = 1.40 ± 0.51 nM) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of LPA (1), OTP (2), GRI977143 (3), and SBA analogues.

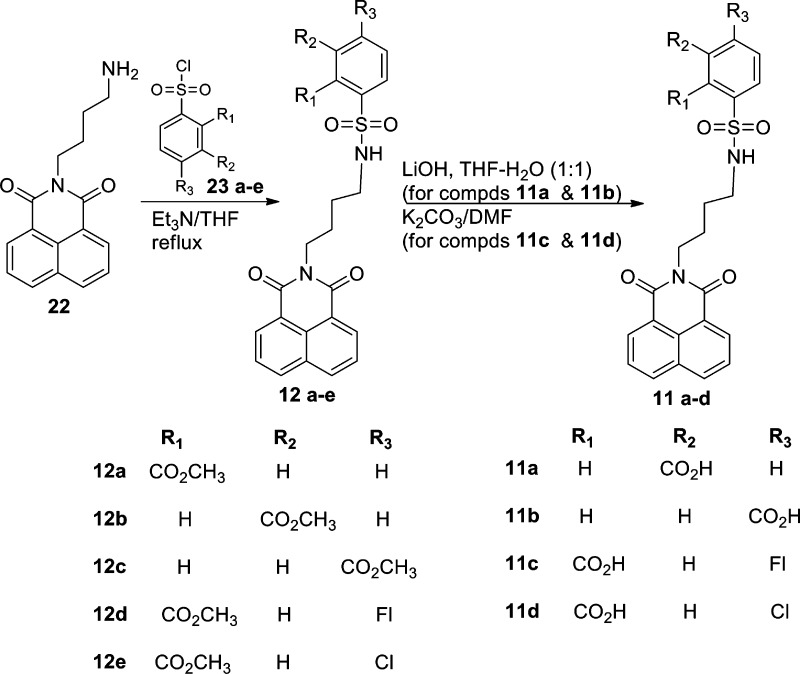

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Head Group Modified SBA Analogues (Compounds 11a–d).

Figure 2.

Fura-2AM Ca2+ assay of 11d versus LPA 18:1. Fura-2AM-loaded LPA2 DKO MEF cells (closed symbols) or empty vector DKO MEF cells (open symbols) were treated with LPA 18:1 (circles) or 11d (squares).

Results and Discussion

The synthesis of new novel SBA analogues, compounds 4–6, 7a–b, 8a–c, 9–10, and 11a–d, is outlined in Schemes 1–4, respectively.

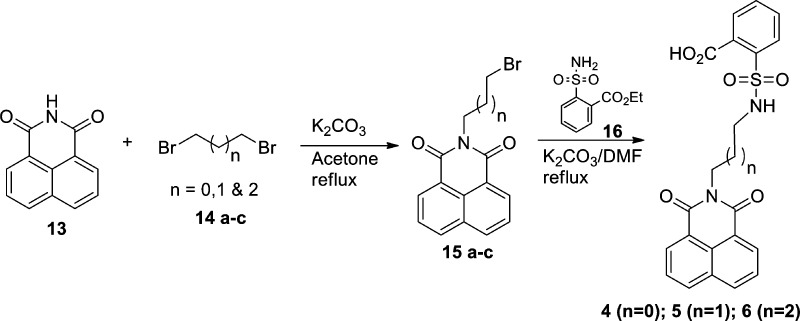

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Carbon Linker Modified SBA Analogues (Compounds 4–6).

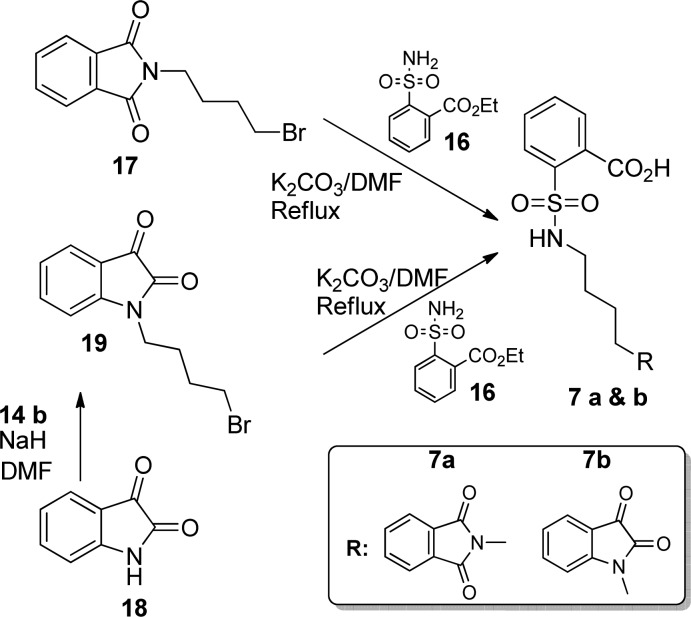

2-(Bromoalkyl)benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3-dione (15a–c) was obtained in high yield following a similar approach of that already reported procedure.13 Compound 15a–c was reacted with 2-sulfamoylbenzoic acid ethyl ester (16) using K2CO3 in DMF to get compounds 4–6 in moderate yield (Scheme 1). 2-[4-(1,3-Dioxo-1,3-dihydroisoindol-2-yl)butylsulfamoyl]benzoic acid (7a) and 2-(N-(4-(2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)butyl)sulfamoyl)benzoic acid (7b) were synthesized by the reaction of commercially available 2-(3-bromobutyl)isoindole-1,3-dione (17) and 1-(4-bromobutyl)indoline-2,3-dione (19) (which was prepared from 14b and isatin 18) using 16, respectively (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Tail Group Modified SBA Analogues (Compounds 7a,b).

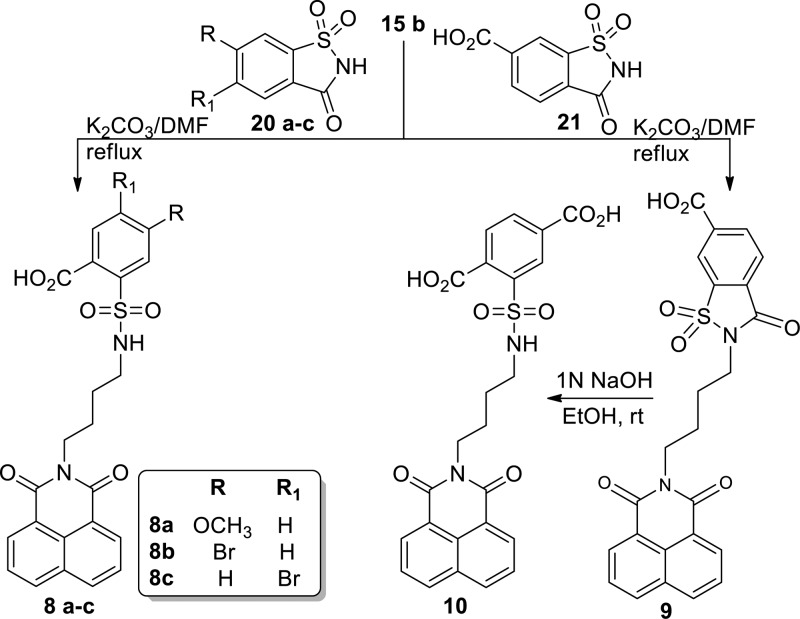

2-(N-(4-(1,3-Dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)butyl)sulfamoyl)-substituted benzoic acid (8a–c) was accomplished by the reaction of 15b and substituted benzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one-1,1-dioxides (20a–c) in the presence of K2CO3 and DMF under reflux conditions in moderate yield. Reaction of 15b with 3-oxo-2,3-dihydrobenzo[d]isothiazole-6-carboxylic acid 1,1-dioxide (21) produced 2-(4-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)butyl)-3-oxo-2,3-dihydrobenzo[d]isothiazole-6-carboxylic acid 1,1-dioxide (9), which was then treated with aqueous 1N NaOH to procure the desired compound 2-(N-(4-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)butyl)sulfamoyl)terephthalic acid (10) (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Head Group Modified SBA Analogues (Compounds 8–10).

N-Butylamino-1,8-naphthalimide (22)14 was coupled with substituted sulfonyl chloride 23a–e using triethylamine in THF to furnish corresponding ester derivatives (12a–e). Upon treatment of compound 12b–c with LiOH in THF–water (1:1) and compound 12d–e with K2CO3 in DMF afforded the final acid derivatives 11a–b and 11c–d, respectively, in moderate to quantitative yield (Scheme 4).

LPA receptor activation leads to a transient mobilization of Ca2+ that can be quantified by measuring the fluorescence of the indicator dye Fura-2AM. All compounds were tested using cell lines established previously to overexpress a single LPA GPCR subtype.10,11 For the human LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3 GPCR, we used mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) derived from LPA1xLPA2 double knockout mice (DKO) that lack endogenous LPA3 expression and do not respond to LPA with Ca2+ transients (for assay details and the LPA4 and LPA5 cells, see the Supporting Information). The compounds were evaluated for agonist and antagonist activity (Table 1). For agonists compounds, their dose–response was compared to that elicited by LPA 18:1 using a FLEX-Station III robotic plate reader as described in our previous publication.10

Table 1. LPA Receptor Ligand Properties of Sulfamoyl Benzoic Acid (SBA) Analogues.

| LPA2 |

LPA1 |

LPA3 |

LPA4 |

LPA5 |

vectorc |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μM) | Emax (%) |

| LPA 18:1 | 0.002 | 100 | 0.35 | 100 | 0.83 | 100 | 0.26 | 100 | 0.51 | 100 | NE | |

| GRI-977143 | 3.30 | 75 | NEa | NE | NEb | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 4 | 2.16 | 100 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 5 | 0.11 | 100 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 6 | 1.42 | 100 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 7a | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 7b | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 8a | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 8b | 0.05 | 100 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 8c | 0.06 | 104.15 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 9 | 3.60 | 100 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 10 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 11a | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 11b | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 11c | 1.5 × 10–4 | 119 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| 11d | 5.06 × 10–6 | 124 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

NE: no detectable effect up to 10 μM concentration.

GRI-977143 has no agonist activity at LPA3, however, it is an antagonist with an IC50 concentration of 6.6. μM against LPA 18:1

Vector control cells were DKO MEF (LPA2), RH7777 (LPA1/3), CHO (LPA4), and B103 (LPA5) transfected with the human LPA receptor orthologue (in parentheses) or transduced with appropriate empty vector. EC50 concentration is given in μM for dose–response curves covering the 0.0001 nM to 10 μM range. For determination of antagonist action, dose–response curves were generated using an ∼Emax50 concentration of LPA 18:1 for any given LPA receptor subtype, and the ligand was coapplied in concentrations ranging from 30 nM to 10 μM. Means represent the mean values of three assays.

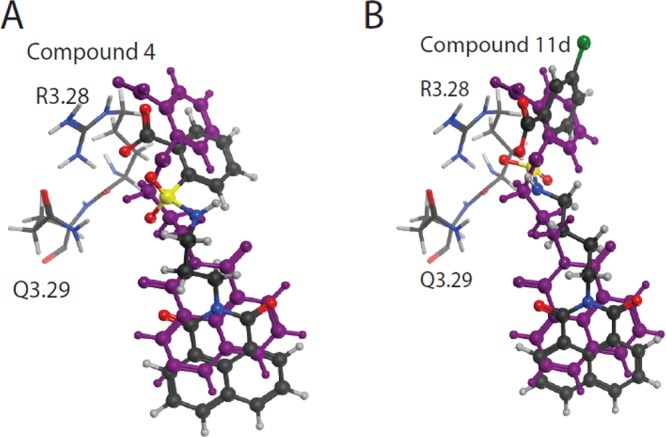

We embarked on a scaffold derivatization approach steered by structure-based pharmacophore design. Studies were initiated with GRI977143 (3) as a template scaffold with the aim of achieving LPA2 subtype agonist specificity by eliminating LPA3 antagonist activity and improving its potency through molecular modifications. Our approach was to prioritize the scaffold variants through several iterative steps. Ten different scaffolds based on 3 were flexibly docked into the LPA2 homology model10,11 and first ranked by lowest energy docked score. Each scaffold was then ranked based on the protein–ligand interaction fingerprint, and a final ranking was constructed based on visual inspection of pharmacophore match. Using this strategy in combination with perceived ease of synthesis, 2-(N-(3-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)propyl)sulfamoyl)benzoic acid (4) was selected. Compound 4 had virtually identical overlay with respect to the shape of 3 where sulfur was replaced by a sulfamoyl moiety (Figure 1). Molecular modeling studies comparing compounds 3 and 4 suggested that the improved potency and selectivity of compound 4 was attributed to the increased binding affinity of compound 4 (−8.53 kcal/mol) compared to compound 3 (−7.94 kcal/mol). While both compounds can adopt similar conformations in the binding pocket, compound 4 has a higher conformation strain at 12.39 kcal/mol than compound 3 at 4.32 kcal/mol (Figure 3A). The pharmacological characterization of compound 4 at LPA2 showed that, in spite of its low potency (EC50 LPA2 ∼ 2 μM), it was a specific agonist of LPA2 without activating or inhibiting LPA1/3/4/5 receptors. Of note is that, unlike GRI977143, compound 4 lacked LPA3 antagonist activity up to 10 μM, the highest concentration tested (Table 1). Therefore, this scaffold 4 was deemed an optimal template for guiding lead optimization medicinal chemistry. Medicinal chemistry focused SAR to increase the potency by synthesizing derivatives of compound 4 by modifying at three target regions: the head group, chain linker, and tail group (Figure 1). We docked and evaluated the chain linker of compound 4 by increasing the carbon numbers to four carbon (compound 5) and five carbon (compound 6) linkers, which are similar in length to the high-potency natural ligand LPA 18:1 of the LPA2. Computational models of the docked linker analogues predicted the overall length of compounds of these analogues at 14, 15, and 16 Å, respectively. Pharmacological characterization of these three compounds 4, 5, and 6 showed that compound 5 with a four carbon linker had the highest potency, lowering the EC50 value of the compound from the micromolar to the nanomolar range. Thus, the optimal length of these analogues is at or near 15 Å that is the same as of LPA 18:1 (Scheme 1 and Table 1). In continuation of our SAR, we explored the modifications of compound 4 by keeping the linker length fixed at four carbons. We replaced the 1H-benzo[de]isoquinolyl-1,3(2H)-dione tail group with isoindolyl-1,3-dione (17) or indolyl-2,3-dione (18) to obtain compounds 7a and 7b, respectively. These two changes abolished the activation of LPA2 up to 10 μM, the highest concentration tested. These tail groups are predicted to occupy a highly hydrophobic region in the LPA binding pocket. Modeling of the tail groups of compounds 7a and 7b in the LPA2 binding pocket predicts several missing π–π interactions (Supporting Information Figure 1), which is the reason for their lack of activity. In our final SAR modifications, we modified the phenyl head group of compound 4. We replaced the hydrogen, which is para to the carboxy group in compound 4 by an electron donating methoxy group or withdrawing bromo group yielded compounds 8a and 8b, respectively. Compound 8a showed very weak agonist activity, whereas compound 8b was more potent than compound 4. We also introduced dicarboxy groups on the head group to improve the potency because previous analysis of intramolecular pH predicted that two negative charges of the LPA phosphate interact with the receptor.10 During the synthesis of the dicarboxy analogue (compound 10), we obtained a cyclized intermediate compound 9, which was further hydrolyzed to dicarboxy analogue 10. Compound 10 was considerably less potent than the compound 9. Next we turned our attention to introduce the electron withdrawing groups. Fluoro, chloro, and bromo substitutions in meta position to the carboxy group of compound 4 produced compounds 11c, 11d, and 8c, respectively. Among these three analogues, compound 11d exhibited picomolar activity (EC50 (nM): 5.06 × 10−3 ± 3.73 × 10–3 vs LPA 18:1; 1.40 ± 0.51), whereas compounds 11c and 8c showed 0.15 ± 0.02 nM and 60.90 ± 9.39 nM, respectively.

Figure 3.

Docked positions of compound 4 (A) and compound 11d (B), shown overlaid on compound 3 (purple) in the LPA2 binding pocket. Critical residues for receptor activation are shown in stick. Compounds were docked and energy minimized using the Molecular Operating Environment, version 2009.10 software (Chemical Computing Group Inc., 2012).

Molecular docking simulations revealed that the addition of halogens at the para position would lead to compounds with a conformation strain similar to compound 3. Compound 11d is predicted to share approximately the same distance in critical interactions with R3.28 and Q3.29 as compounds 3 and 4, however, compound 11d binding affinity is −9.21 kcal/mol and conformation strain is 6.50 (Figure 3B). To complete our SAR studies, finally we prepared additional two compounds where we changed the position of carboxy group on the head group of phenyl ring of compound 4 from ortho to meta (compound 11a) and para (compound 11b) positions that abolished the activity at LPA2. The corresponding methyl carboxy esters of compounds 5 and 11a–d (compound 12a–e) were also inactive at activating LPA2 up to 10 μM, the highest concentration tested.

Conclusion

Here we designed and synthesized new SBA analogues using a structure-based pharmacophore. Starting from our active scaffold 4, the detailed structure–activity relationship profile was established to understand the effect of particular substituents on head and tail groups along with carbon linker. We concluded that three important structural requirements are critical to have potent and specific LPA2 agonistic activity; (i) four carbon chain linker, (ii) keeping the same tail group 1H-benzo[de]isoquinolyl-1,3(2H)-dione, and (iii) introducing the electron withdrawing group such as chloro meta to the carboxy group of compound 4. This approach yielded compound 11d, which is the first nonlipid specific agonist of LPA2 with picomolar affinity.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

All compounds were analyzed by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, MASS, and HRMS. The purity of final compounds was ≥95% as measured by HPLC. Full experimental procedures can be found in the Supporting Information.

Analytical Data for Compound 11d

Yield 53%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) d 9.13 (bs, 1H), 8.52–8.44 (m, 4H), 7.88–7.85 (m, 2H), 7.71–7.68 (m, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dd, J = 2.0 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.99 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.65–1.57 (m, 2H), 1.47–1.39 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) d 167.67, 163.38, 136.53, 135.18, 134.29, 131.28, 130.73, 130.19, 129.23, 127.35, 127.20, 127.12, 122.01, 42.72, 40.11, 26.73, 25.01. MS (ES−) m/z 485 (M – H)−. HPLC purity: tR = 2.23, 98.09%. HRMS calcd for C23H19ClN2O6S, 487.0731 (M – H)−; found, 487.0737.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID AI080405 to G. T.), the American Cancer Society (ACS 122059-PF-12-107-01-COD to J.I.F.), the Van Vleet Endowment (G. T.) and by Award Number I01BX007080 from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development (G.T.).

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- K2CO3

potassium carbonate

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- RT

room temperature

- SBA

sulfamoyl benzoic acid

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details of chemical synthesis, computational and biological tests. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ R.P. and J.I.F. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): G.T. and D.M. are founders and stock holders of RxBio Inc.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- E S.; Lai Y. J.; Tsukahara R.; Chen C. S.; Fujiwara Y.; Yue J.; Yu J. H.; Guo H.; Kihara A.; Tigyi G.; Lin F. T. Lysophosphatidic acid 2 receptor-mediated supramolecular complex formation regulates its antiapoptotic effect. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14558–14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss G. N.; Lee S. C.; Fells J. I.; Liu J.; Valentine W. J.; Fujiwara Y.; Thompson K. E.; Yates C. R.; Sumegi B.; Tigyi G. Mitigation of radiation injury by selective stimulation of the LPA(2) receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1831, 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F. T.; Lai Y. J.; Makarova N.; Tigyi G.; Lin W. C. The lysophosphatidic acid 2 receptor mediates down-regulation of Siva-1 to promote cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37759–37769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigyi G. Aiming drug discovery at lysophosphatidic acid targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 161, 241–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W.; Balazs L.; Wang D. A.; Van Middlesworth L.; Tigyi G.; Johnson L. R. Lysophosphatidic acid protects and rescues intestinal epithelial cells from radiation- and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W.; Poppleton H.; Yasuda S.; Makarova N.; Shinozuka Y.; Wang D. A.; Johnson L. R.; Patel T. B.; Tigyi G. Optimal lysophosphatidic acid-induced DNA synthesis and cell migration but not survival require intact autophosphorylation sites of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47871–47880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W.; Shuyu E.; Tsukahara R.; Valentine W. J.; Durgam G.; Gududuru V.; Balazs L.; Manickam V.; Arsura M.; VanMiddlesworth L.; Johnson L. R.; Parrill A. L.; Miller D. D.; Tigyi G. The lysophosphatidic acid type 2 receptor is required for protection against radiation-induced intestinal injury. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1834–18351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke M.; Zhao Z.; Xu Y.; Chun J.; Tager A. M. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 promotes epithelial cell apoptosis after lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furui T.; LaPushin R.; Mao M.; Khan H.; Watt S. R.; Watt M. A.; Lu Y.; Fang X.; Tsutsui S.; Siddik Z. H.; Bast R. C.; Mills G. B. Overexpression of edg-2/vzg-1 induces apoptosis and anoikis in ovarian cancer cells in a lysophosphatidic acid-independent manner. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 4308–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss G. N.; Fells J. I.; Gupte R.; Lee S. C.; Liu J.; Nusser N.; Lim K. G.; Ray R. M.; Lin F. T.; Parrill A. L.; Sumegi B.; Miller D. D.; Tigyi G. Virtual screening for LPA2-specific agonists identifies a nonlipid compound with antiapoptotic actions. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 82, 1162–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Y.; Sardar V.; Tokumura A.; Baker D.; Murakami-Murofushi K.; Parrill A.; Tigyi G. Identification of residues responsible for ligand recognition and regioisomeric selectivity of lysophosphatidic acid receptors expressed in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 35038–35050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardar V. M.; Bautista D. L.; Fischer D. J.; Yokoyama K.; Nusser N.; Virag T.; Wang D. A.; Baker D. L.; Tigyi G.; Parrill A. L. Molecular basis for lysophosphatidic acid receptor antagonist selectivity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1582, 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A.; Ramu R.; Tekumalla V.; Khanna G. B.; Barkume M. S.; Juvekar A. S.; Zingde S. M. Remarkable DNA binding affinity and potential anticancer activity of pyrrolo[2,1-c][1,4]benzodiazepine–naphthalimide conjugates linked through piperazine side-armed alkane spacers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 7218–7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumiatti V.; Milelli A.; Minarini A.; Micco M.; Gasperi Campani A.; Roncuzzi L.; Baiocchi D.; Marinello J.; Capranico G.; Zini M.; Stefanelli C.; Melchiorre C. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of substituted naphthalene imides and diimides as anticancer agent. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7873–7877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.