We measured in vitro phenotypes of early Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from children with cystic fibrosis in an antibiotic eradication therapy trial. Isolates frequently exhibited phenotypes associated with chronic adaptation. Two phenotypes were correlated with failure to eradicate, representing promising candidate markers.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, phenotypic characterization, eradication, antibiotic treatment

Abstract

Background. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a key respiratory pathogen in people with cystic fibrosis (CF). Due to its association with lung disease progression, initial detection of P. aeruginosa in CF respiratory cultures usually results in antibiotic treatment with the goal of eradication. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits many different phenotypes in vitro that could serve as useful prognostic markers, but the relative relationships between these phenotypes and failure to eradicate P. aeruginosa have not been well characterized.

Methods. We measured 22 easily assayed in vitro phenotypes among the baseline P. aeruginosa isolates collected from 194 participants in the 18-month EPIC clinical trial, which assessed outcomes after antibiotic eradication therapy for newly identified P. aeruginosa. We then evaluated the associations between these baseline isolate phenotypes and subsequent outcomes during the trial, including failure to eradicate after antipseudomonal therapy, emergence of mucoidy, and occurrence of an exacerbation.

Results. Baseline P. aeruginosa isolates frequently exhibited phenotypes thought to represent chronic adaptation, including mucoidy. Wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges were both associated with increased risk of eradication failure (hazard ratios [95% confidence intervals], 1.99 [1.03–3.83] and 2.14 [1.32–3.47], respectively). Phenotypes reflecting defective quorum sensing were significantly associated with subsequent mucoidy, but no phenotype was significantly associated with subsequent exacerbations during the trial.

Conclusions. Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenotypes commonly considered to reflect chronic adaptation were observed frequently among isolates at early detection. We found that 2 easily assayed colony phenotypes were associated with failure to eradicate after antipseudomonal therapy, both of which have been previously associated with altered biofilm formation and defective quorum sensing.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Waters on pages 632–4.)

People with cystic fibrosis (CF) have chronic airway infections with various microbes. Among these, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) is among the most common, and infection with Pa is associated with significantly poorer CF lung disease outcomes [1]. Young children with CF have a relatively low prevalence of Pa culture positivity, but the risk increases with age, with a peak prevalence of nearly 80% among adults with CF [2]. Due to its association with worse lung disease, Pa is a target for early antibiotic eradication therapy [3–8].

Previous studies of Pa isolates from CF infections demonstrated that these bacteria undergo diverse phenotypic and genetic changes over time [9–13]. Perhaps the best-known change is the emergence of a colony phenotype known as mucoidy [14]. Previous studies indicated that mucoidy is rare among environmental or non-CF Pa [15] and in early CF [16], but emerges on average after approximately 11 years of infection [14]. Mucoidy has also been associated with more severe lung disease [14, 17]. Recently, inactivating mutations in lasR, which encodes a transcriptional regulator in an intercellular signaling pathway known as quorum sensing, have also been shown to occur frequently during chronic CF Pa infections [10, 18, 19]. Prior studies indicated that lasR mutations occurred earlier on average than mucoidy and were associated with more severe lung disease [19]. Decreases in antibiotic susceptibilities [20] and altered production of the pigment pyocyanin [21] were also associated with advanced age and lower lung function in studies focused on those phenotypes. Many other Pa adaptive changes, including alterations in cell motility, metabolism, virulence, DNA mismatch repair, and secreted molecule production, have been identified [11–13], but less is known about their relationships with clinical outcomes. Moreover, few studies have compared the prognostic values of different Pa phenotypes [22, 23].

The advent of newborn screening for CF has enabled early surveillance for Pa infection and the prompt initiation of antibiotic eradication therapy upon Pa detection. The ability to predict failure of eradication by measuring characteristics of Pa isolates from early infection is therefore of interest. One previous study attempted to correlate Pa phenotypes at initial detection with eradication after antibiotic treatments, but no predictive characteristics were identified [22]. In addition, in vitro antibiotic susceptibilities have been shown not to correlate with Pa eradication after antimicrobial therapy [22, 23]. These studies highlight the need for clinically useful predictors of eradication, which could identify patients who might benefit from more aggressive initial antibiotic treatment.

A recent multicenter clinical trial, the Early Pseudomonas Infection Control (EPIC) clinical trial [24], compared different antibiotic eradication strategies for newly identified Pa among children with CF. Children aged 1–12 years were randomized to receive 1 of 2 antipseudomonal antibiotic regimens and were followed for 18 months, with the goal of comparing safety and efficacy between regimens. The trial demonstrated comparable effectiveness across all endpoints between antibiotic treatment strategies, including successful Pa eradication for up to 18 months after initial antibiotic therapy [24]. However, 34% of trial participants failed to eradicate Pa, with a subsequent Pa-positive culture after the initial antibiotic course and during the remainder of the 18-month trial. Further studies in this subject group could not identify baseline clinical factors or patterns of infection that predicted eradication failure [25]. This study presented an ideal opportunity to determine whether there are Pa characteristics that correlate with poor microbiologic and clinical outcomes.

We therefore characterized the baseline Pa isolates from participants enrolled in the EPIC clinical trial using a panel of 22 in vitro phenotypic tests, which we selected both for prior evidence that they exhibit adaptive change in CF and because they were simple and reproducible in high-throughput format. Our aim was to identify a panel of useful, easily measured tests that could potentially be used clinically to predict failure to eradicate after antimicrobial therapy.

METHODS

Cohort Selection

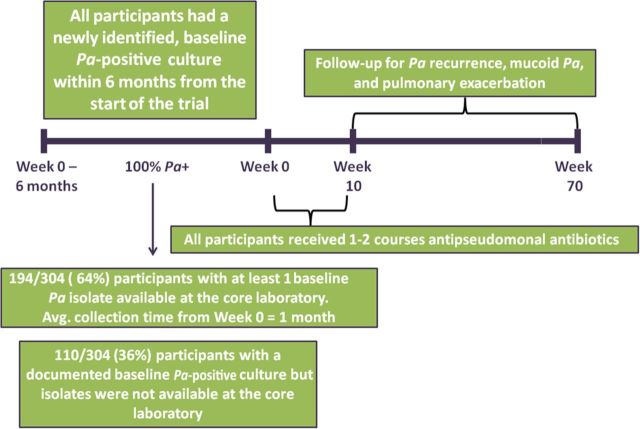

The study cohort was comprised of participants from the EPIC clinical trial (Figure 1) (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00097773) [24]. All participants with isolates from the screening visit or from the 6 months prior to enrollment (“baseline” isolates) were included in this study. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Seattle Children's Hospital. Complete details regarding the study cohort and study design are in the Supplementary Data.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design. Abbreviation: Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was time to Pa eradication failure, defined as the first occurrence of a Pa-positive culture after the initial quarter of antipseudomonal antibiotic therapy. During the clinical trial, respiratory cultures (oropharyngeal or sputum) were obtained during follow-up at weeks 10, 22, 34, 46, 58, and 70 (<4% of children had sputum available at each visit). Secondary endpoints included the proportion of participants with emergent mucoid Pa and time to pulmonary exacerbation during the 15-month follow-up period. Details regarding the definitions of study endpoints, as well as culture processing, are in the Supplementary Data.

Phenotyping and Genotyping of Pa Isolates

All Pa clinical isolates collected at study sites were characterized centrally in 1 laboratory after minimal passaging. Phenotypic analysis and lasR gene sequencing were performed using tests found to be reproducible in multiple replicates and in high-throughput format, using quantitative measures (including for colorimetric analysis) when possible to minimize bias. Full details regarding these tests are included in the Supplementary Data.

Statistical Analysis

Details of the statistical analysis approaches for estimating the association between Pa isolate characteristics and clinical outcomes are described in the Supplementary Data.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Of the 304 trial participants, 194 of 304 (64%) had baseline Pa isolates available at the core microbiology laboratory (284 isolates total) and were included in the study cohort. Table 1 compares this participant subgroup with those with newly identified Pa positivity but who did not have baseline isolates available. No significant differences were found between participants with and without available baseline Pa isolates, although slightly more participants with first lifetime documentation of Pa had baseline isolates available (9% more; 95% confidence interval [CI], −2% to 20%).

Table 1.

Baseline Cohort Characteristics

| Characteristic | Baseline Pa Isolates Available (n = 194) |

Baseline Pa Isolates Missing (n = 110) |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 96 (49%) | 54 (49%) |

| Age at baseline, y, mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.5) | 5.9 (3.6) |

| Age distribution at baseline | ||

| 1–3 y | 61 (31%) | 29 (26%) |

| >3–6 y | 54 (28%) | 30 (27%) |

| >6–12 y | 79 (41%) | 51 (46%) |

| Genotype | ||

| F508 del homozygous | 96 (49%) | 53 (48%) |

| F508 del heterozygous | 78 (40%) | 38 (35%) |

| Other/unknown | 20 (10%) | 19 (17%) |

| First lifetime Pa-positive culture | 139 (72%) | 69 (63%) |

| Any antibiotic use | ||

| Birth to prebaseline | 128 (66%) | 71 (65%) |

| Prebaseline to baseline | 68 (35%) | 59 (54%) |

| Baseline weight, kg, mean (SD) | 20.1 (9.4) | 21.5 (11.1) |

| Baseline height, cm, mean (SD) | 107.9 (22.4) | 109.7 (23.9) |

| FEV1, La, mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| FEV1 % predicteda, mean (SD) | 94.7 (17.0) | 98.5 (16.0) |

| Coinfection with Staphylococcus aureus | 105 (56%) | 65 (61%) |

| Coinfection with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 7 (4%) | 4 (4%) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; SD, standard deviation.

a Ninety-three participants had baseline spirometry among those with baseline Pa isolates available. Sixty-two participants had baseline spirometry for those missing baseline Pa isolates.

Baseline Prevalence of Pa Phenotypic Characteristics

Figure 2 displays the prevalence of each tested phenotypic characteristic among isolates from baseline cultures. Supplementary Figures 1–4 display examples of phenotypes of particular relevance for this study. Besides wild-type tan colony color, pyocyanin production during in vitro liquid growth was the most prevalent assayed phenotype at baseline, present in 74 of 112 (66%) cultures. Mucoidy was exhibited in 17 of 194 (9%) baseline cultures and auxotrophy by 13 of 194 (7%) cultures. Defects in motility, including swimming (57/194 [29%]) and twitching (31/111 [28%]), were also relatively common among participants' baseline cultures. Defective production of the siderophore pigment pyoverdine was identified among 81 of 112 (72%) cultures. All of these phenotypes, which were variably but clearly common among the baseline isolates, have previously been associated with adaptation to the CF airway during chronic infection [12].

Figure 2.

Prevalence of each phenotype among baseline cultures of the participants in the cohort (N = 194). Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Because our previous work indicated a high prevalence of inactivating mutations in lasR early during chronic CF infections [10, 18, 19] and demonstrated associations of these mutations with worse lung disease and subsequent emergence of mucoidy [19], we sequenced lasR among the baseline isolates. We also characterized several phenotypes shown previously to be conferred by inactivating lasR mutations [10, 19, 26], including colony autolysis and surface sheen, decreased protease production, and increased growth in added nitrate. lasR mutations predicted to be of functional significance were present in 26 of 110 (24%) baseline cultures and, by comparison, autolysis and/or sheen were present in 38 of 194 (20%) cultures, protease production was defective in 68 of 194 (35%) cultures, and increased growth in nitrate was found in 24 of 111 (22%) cultures. Additional phenotypes that were particularly common at baseline included irregular colony edges (46/194 [24%]) and wrinkly colony surface (20/194 [10%]), both of which have been associated with both lasR inactivation and increased biofilm formation [10, 27, 28]. Colony binding of Congo red dye, which stains the exopolysaccharides that confer both mucoidy and biofilm formation, was detected among 41 of 194 (21%) baseline cultures.

Concordance Between Pa Phenotypic Characteristics at Baseline

We characterized the relationships between pairs of assayed characteristics at baseline (Supplementary Table 1). The most significant findings of concordance between phenotypes occurred between colony sectoring and irregular colony edges (kappa [κ] = 0.66), lysis and/or sheen and green colony color (the latter indicative of pyocyanin) (κ = 0.62), lasR mutations predicted to impact function and lysis and/or sheen (κ = 0.57), reduced swimming and reduced protease (κ = 0.56), lasR mutations and green colony color (κ = 0.53), lasR mutations and reduced protease (κ = 0.53), reduced twitching motility and Congo red binding (κ = 0.49), reduced swimming and reduced twitching (κ = 0.46), reduced swimming and Congo red binding (κ = 0.43), lysis and/or sheen and reduced protease (κ = 0.42), and Congo red binding and wrinkly colony surface (κ = 0.41).

Association Between Baseline Pa Phenotypic Characteristics and Failure to Eradicate After Antipseudomonal Therapy

Whereas the proportion of participants failing to achieve Pa eradication was 34% among the entire trial population, in this study cohort (ie, those for whom baseline isolates were available), 79 of 194 (41%) of participants failed to achieve Pa eradication during the study. Table 2 displays results from a multivariable model used to identify which baseline Pa phenotypic characteristics, independent of other baseline factors, were associated with failure to eradicate. As found in the original trial, antibiotic therapy received during the trial was not significantly associated with microbiologic and clinical outcomes in our study and was not included for adjustment in the final model. Wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges were each associated with significantly increased risk of failure to eradicate after antipseudomonal therapy. Figure 3 displays the corresponding Kaplan-Meier curves for these phenotypes. Sensitivity analyses indicated no other significant predictors of failure to eradicate, including coinfection with other organisms and past history of Pa (Table 2). Wrinkly colonies and irregular colony edges (which were not significantly correlated with each other, Supplementary Table 1) remained the most significant predictors of failure to eradicate even after adjustment for these factors (Table 2). This sensitivity analysis was repeated among the subset of participants for whom baseline spirometry was available, yielding similar results.

Table 2.

Results of Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Time to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Recurrence

| Baseline Covariate | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | |||

| Wrinkly colonies | 1.99 | 1.03–3.83 | .040 |

| Irregular colony edges | 2.14 | 1.32–3.47 | .002 |

| Adjusted model | |||

| Wrinkly colonies | 2.18 | 1.08–4.42 | .030 |

| Irregular colony edges | 2.12 | 1.28–3.52 | .003 |

| Age ≤3 y | … | … | … |

| Age >3–6 y | 1.03 | .56–1.92 | .917 |

| Age >6–12 y | 1.37 | .71–2.65 | .349 |

| Male sex | 1.08 | .69–1.70 | .747 |

| Genotype: F508 del homozygous | … | … | … |

| Genotype: F 508 del heterozygous | 1.44 | .89–2.34 | .142 |

| Genotype: other | 0.91 | .37–2.22 | .837 |

| Any antibiotic use | |||

| No. of courses, birth to baseline | 1.03 | .93–1.13 | .609 |

| No prior Pa positivity | … | … | … |

| Pa positive >2 y prior | 0.93 | .49–1.77 | .828 |

| Positive for Staphylococcus aureus | 1.22 | .74–2.00 | .433 |

| Positive for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 0.68 | .16–2.86 | .598 |

| Mucoid Pa | 1.71 | .84–3.46 | .138 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) recurrence by presence of wrinkly colonies and irregular colony edges at baseline.

Associations Between Baseline Pa Phenotypic Characteristics With Emergence of Mucoidy and Risk of Pulmonary Exacerbation

Because mucoidy has been associated with both chronic infection and poor outcomes [14, 17], we determined whether baseline Pa characteristics were associated with subsequent emergence of mucoidy during the 18-month study follow-up period. The presence of either colony autolysis or sheen at baseline was the only characteristic significantly associated with subsequent emergence of mucoidy. A total of 4 of 31 participants (12.9%) with initial isolates exhibiting autolysis and/or sheen had new emergence of mucoid Pa during the trial, compared with 4 of 142 (2.8%) of those without either phenotype (10.1% difference; P= .035). No baseline Pa phenotypes were significantly associated with increased risk of pulmonary exacerbation during the follow-up (not shown).

Biofilm Formation

The 2 colony phenotypes associated with failure to eradicate after antibiotic treatment, wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges, have both been associated with enhanced biofilm formation [10, 27, 28], suggesting a mechanistic link between these colony phenotypes that could indicate their pathophysiologic significance. However, because in vitro biofilm testing is complex and lacks the reproducibility required for high-throughput analysis, we tested a subset of isolates (n = 19 isolates each with wrinkly surface, irregular edges, or neither; total n = 57) with these characteristics for their biofilm-forming abilities in vitro. We found no association between in vitro biofilm formation and either wrinkly colony surface or irregular colony edges (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In contrast to previous reports and traditionally held concepts [14, 28, 29, 30], we found that several Pa in vitro phenotypes commonly considered to represent adaptation during chronic infection occurred frequently among newly identified Pa isolates from children with CF. With the goal of identifying candidate prognostic markers of failure of antibiotic eradication, we assayed phenotypes chosen for prior evidence of undergoing change during chronic CF infections and for their reproducibility, definitive endpoints, and ease of measurement in clinical laboratory settings. Two of these phenotypes, wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges, were significantly associated with subsequent failure to eradicate after antibiotic treatment. These results suggest that Pa isolated from CF respiratory samples during early infection may represent lineages that have adapted to that host (perhaps in the upper airways, or undetected in the lower respiratory tract) or to another host or environment prior to acquisition. If our results are validated, these 2 easy-to-identify colony phenotypes may serve as prognostic markers of eradication failure, potentially identifying patients who may benefit from more aggressive eradication treatment.

A previous study attempted to relate phenotypic characteristics of CF Pa isolates from initial detection with subsequent eradication failure [22]. That study included 52 infection events, focusing on patients with either persistent or eradicated infection, and excluding patients with intermittent Pa detection post–antibiotic treatment. The 9 characteristics examined, in contrast to the 22 assays used here, were generally chosen to represent potential determinants of pathogenicity or antibiotic resistance (eg, cytotoxicity, production of virulence factors, in vitro susceptibilities, and mutation frequencies), rather than prior evidence of adaptive change or clinical utility. The authors found that eradicated isolates were less likely to be cytotoxic than were baseline isolates from persistent infection, but they concluded that it was not possible to predict eradication failure using those tests.

In the current study, mucoidy, an in vitro phenotype traditionally associated with failure of antibiotic treatment, was not significantly associated with eradication failure. This finding contrasts with an earlier study examining aerosolized tobramycin in treating Pa infection among 31 CF patients, which reported that eradication was significantly less likely in patients with mucoid isolates [23]. Those results likely differed from ours because the prior study did not focus exclusively on early infection. Similarly, another study of longitudinally collected Pa isolates identified decreased exoproduct production and decreased motility among isolates from persistent compared with cleared infections [13]. Because that study did not focus on newly detected Pa, those results could also reflect chronic infection.

Our results showed a surprisingly high baseline prevalence of phenotypes traditionally associated with adaptive change during chronic infection [31], including mucoidy [14, 16], defective motility [32], and altered quorum sensing [18, 19]. These “early” isolates could represent adaptation of previously undetected infection in either the upper [13, 33, 34] or lower airways, despite negative cultures; because 94% of specimens in this study were from the oropharynx rather than sputum, our ability to detect lower airway infection was limited [35]. Alternatively, these findings may represent patient-to-patient transmission of preadapted lineages, a possibility that seems unlikely based on previous work suggesting acquisition from environmental sources [12].

In CF, mucoidy has been associated with failure to eradicate with antibiotics [23]. Previous work suggested that mucoidy tends to emerge after an average of a decade of chronic infection [14, 19], a change traditionally interpreted to reflect a chronic infection phenotype [1, 12]. Our finding that early Pa isolates from 9% of participants exhibited mucoidy not significantly associated with failure to eradicate after antibiotics raises questions about the prognostic significance of this phenotype in early infection. We also confirmed and extended our previous study results [19] that autolysis and/or sheen (indicators of LasR inactivation [10]) preceded the emergence of mucoidy. Additional larger longitudinal studies will be required to clarify the natural history of Pa adaptive changes and the relative prognostic utility of each characteristic with respect to long-term clinical outcomes.

The 2 colony phenotypes that were associated with failure to eradicate after antibiotics, wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges, have both been associated previously with altered quorum sensing and increased biofilm formation [27, 28], suggesting these colony phenotypes could be markers for 1 or both of these other characteristics. However, we did not identify associations between these colony phenotypes and either in vitro biofilm formation or lasR mutation. Therefore, the mechanism with which isolates with these phenotypes persist, if any, is not yet clear, and the prognostic utility of these phenotypes in predicting failure of eradication must be confirmed in a prospective study.

Prior work demonstrated that in vitro antibiotic susceptibilities of Pa isolates correlate poorly with subsequent CF clinical outcomes [36], including eradication with antibiotics [22, 23]. Thus, we did not include susceptibility testing. Similarly, we did not assay other Pa characteristics found previously to change during chronic CF infections, either due to difficulty adapting those assays for high-throughput testing, expense, or poor reproducibility. Among these characteristics are type III secretion and cytotoxicity, metabolic changes, growth in sputum or under anaerobic conditions, hypermutability, membrane changes, and serum sensitivity [9, 11, 12]. We also only assayed biofilm formation on a subset of isolates due to issues with assay complexity and reproducibility. These characteristics represent potential future study possibilities.

There are several potential limitations of this work. For instance, recent studies showed that traditional culture methods (ie, isolating a small number of morphologically different bacterial colonies) frequently underrepresent the Pa diversity in individual samples of CF respiratory secretions during chronic infection with respect to antibiotic susceptibilities [37], quorum sensing [38], and other phenotypes [39, 40]. A second limitation is that study participants with lifetime histories of Pa positivity must have had a 2-year history of Pa-negative cultures, but required only 1 culture result in each of the 2 years. Although it is possible that participants with a lifetime history of Pa with fewer cultures during those 2 years could have been found to have more advanced Pa infection if sampled more frequently, our analyses did not identify associations between lifetime Pa history and any outcome of interest. Last, while this study is, to our knowledge, the largest comparative phenotypic analysis of its kind, the sample size may still have been insufficient to identify some relationships with failure to eradicate, emergence of mucoidy, or exacerbations. Additional study of larger isolate collections may clarify this issue.

In conclusion, we found that 2 easily identified Pa colony phenotypes, wrinkly colony surface and irregular colony edges, were associated with subsequent eradication failure. In addition, the in vitro phenotypes exhibited by baseline isolates suggest that Pa may have already adapted to host environments by the time it is first detected. Further studies of the predictive utility of these phenotypes are required to confirm these findings and to determine whether these phenotypes correlate with longer-term clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors gratefully acknowledge Sharon McNamara and Julia Emerson for study design and isolate collection input; Lynette Browne and Kelli Joubran for analytic programming support; Jessica Foster for processing of the isolates; and the families and children with cystic fibrosis who participated in the EPIC study.

Financial support. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers R01HL098084, K02HL105543, P30DK089507), and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics (CFFT).

Potential conflicts of interest. N. M.-H. receives grant support from CFFT and the NIH; is the principal investigator of an investigator-initiated grant supported by Novartis for which she receives salary support; and serves on an advisory committee for Insmed, for which her institution receives payment. B. W. R. receives grant support from the CFFT and NIH; and has received support from the following companies through her role as Director of the CFTDN Coordinating Center: Apartia, Bayer Healthcare AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Grifols Therapeutics, Inc, Hall Bioscience, Insmed Incorporated, Kalobios, Rempex Pharmaceuticals, N30 Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Nikan Pharmaceuticals, Nordmark, Novartis Phamaceuticals Corporation, Pulmatrix, Savara Pharmaceuticals, Talecris, Vectura Ltd, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc, 12th Man Technologies, Achaogen, Celtaxys, Cornerstone Therapeutics, Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Breathe Easy, Ltd, CSL Behring LLC, INC Research, Pharmaxis Ltd, PumoFlow, and Respira Therapeutics, Inc. G. R.-B. receives grant support from the NIH and CFFT, and a limited portion of his institutional salary is also supported by industry-sponsored trials within the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Savara Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Science, Inc, and PTC Therapeutics). J. L. B. receives grant support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the NIH and receives salary support from clinical research study contracts from Grifols, KaloBios, and Novartis. M. R. receives grant support from the NIH, CFFT, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. R. L. G. receives grant support from the CFFT and NIH; a limited portion of his institutional salary is also supported by industry-sponsored trials within the CFF Therapeutics Development Network including Vertex Pharmaceuticals. L. R. H. receives grant funding from the CFFT and NIH. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:918–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient registry report. 2012. Available at: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport/2012-CFF-Patient-Registry.pdf . Accessed 2 June 2014.

- 3.Valerius NH, Koch C, Høiby N. Prevention of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation in cystic fibrosis by early treatment. Lancet. 1991;338:725–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiesemann HG, Steinkamp G, Ratjen F, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of aerosolized tobramycin for early treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998;25:88–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199802)25:2<88::aid-ppul3>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson RL, Emerson J, McNamara S, et al. Significant microbiological effect of inhaled tobramycin in young children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:841–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proesmans M, Vermeulen F, Boulanger L, Verhaegen J, De Boeck K. Comparison of two treatment regimens for eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langton Hewer SC, Smyth AR. The Cochrane Collaboration. Antibiotic strategies for eradicating Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis. In: Langton Hewer SC, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD004197.pub3 . Accessed 21 November 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratjen F, Munck A, Kho P, Angyalosi G ELITE Study Group. Treatment of early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: the ELITE trial. Thorax. 2010;65:286–91. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Döring G, Parameswaran IG, Murphy TF. Differential adaptation of microbial pathogens to airways of patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:124–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Argenio DA, Wu M, Hoffman LR, et al. Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:512–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folkesson A, Jelsbak L, Yang L, et al. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cystic fibrosis airway: an evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:841–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogardt M, Heesemann J. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during persistence in the cystic fibrosis lung. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:557–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manos J, Hu H, Rose BR, et al. Virulence factor expression patterns in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from infants with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1583–92. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Kosorok MR, Farrell PM, et al. Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2005;293:581–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doggett RG. Incidence of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa from clinical sources. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:936–7. doi: 10.1128/am.18.5.936-937.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilligan PH. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:35–51. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S, Ramsey B, Gibson RL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34:91–100. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8487–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman LR, Kulasekara HD, Emerson J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease progression. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren CL, Konstan MW, Yegin A, et al. Multiple antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and lung function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter RC, Klepac-Ceraj V, Lorenzi MM, Grotzinger H, Martin TR, Newman DK. Phenazine content in the cystic fibrosis respiratory tract negatively correlates with lung function and microbial complexity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:738–45. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tramper-Stranders GA, van der Ent CK, Molin S, et al. Initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: characteristics of eradicated and persistent isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:567–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson RL, Emerson J, Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Duration of treatment effect after tobramycin solution for inhalation in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:610–23. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treggiari MM, Retsch-Bogart G, Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of 4 randomized regimens to treat early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:847–56. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer-Hamblett N, Kronmal RA, Gibson RL, et al. Initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa treatment failure is associated with exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:125–34. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman LR, Richardson AR, Houston LS, et al. Nutrient availability as a mechanism for selection of antibiotic tolerant Pseudomonas aeruginosa within the CF airway. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000712. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R, Schuster M. Quorum sensing modulates colony morphology through alkyl quinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Argenio DA, Calfee MW, Rainey PB, Pesci EC. Autolysis and autoaggregation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa colony morphology mutants. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6481–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6481-6489.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns JL, Gibson RL, McNamara S, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in young children with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:444–52. doi: 10.1086/318075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch C. Early infection and progression of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34:232–6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser AR, Jain M, Bar-Meir M, McColley SA. Clinical significance of microbial infection and adaptation in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:29–70. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahenthiralingam E, Campbell ME, Speert DP. Nonmotility and phagocytic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from chronically colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:596–605. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.596-605.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cramer N, Wiehlmann L, Tümmler B. Clonal epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:526–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen SK, Rau MH, Johansen HK, et al. Evolution and diversification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the paranasal sinuses of cystic fibrosis children have implications for chronic lung infection. ISME J. 2012;6:31–45. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Accurso F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of oropharyngeal cultures in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28:321–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199911)28:5<321::aid-ppul3>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AL, Fiel SB, Mayer-Hamblett N, Ramsey B, Burns JL. Susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates and clinical response to parenteral antibiotic administration: lack of association in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2003;123:1495–502. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foweraker JE, Laughton CR, Brown DFJ, Bilton D. Phenotypic variability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputa from patients with acute infective exacerbation of cystic fibrosis and its impact on the validity of antimicrobial susceptibility testing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:921–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilder CN, Allada G, Schuster M. Instantaneous within-patient diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing populations from cystic fibrosis lung infections. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5631–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00755-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Workentine ML, Sibley CD, Glezerson B, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in a cystic fibrosis patient. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashish A, Paterson S, Mowat E, Fothergill JL, Walshaw MJ, Winstanley C. Extensive diversification is a common feature of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations during respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12:790–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.