Abstract

Frustrated Lewis pairs have found many applications in the heterolytic activation of H2 and subsequent hydrogenation of small molecules through delivery of the resulting proton and hydride equivalents. Herein, we describe how H2 can be preactivated using classical frustrated Lewis pair chemistry and combined with in situ nonaqueous electrochemical oxidation of the resulting borohydride. Our approach allows hydrogen to be cleanly converted into two protons and two electrons in situ, and reduces the potential (the required energetic driving force) for nonaqueous H2 oxidation by 610 mV (117.7 kJ mol–1). This significant energy reduction opens routes to the development of nonaqueous hydrogen energy technology.

Introduction

H2 is attractive as a “clean” fuel source, leading to a vast body of literature concerned with fuel cell technology.1,2 In the absence of an appropriate electrocatalyst (defined as a system that reduces the overpotential, the required energetic driving force, and/or increases the rate of electron transfer), the nonaqueous oxidation of H2 to liberate two protons and two electrons is slow, requiring large overpotentials (often in excess of 1000 mV vs Cp2Fe0/+ at carbon electrodes) and producing broad, ill-defined oxidation waves. Conventional, predominantly aqueous, fuel cells surmount this problem by using precious metals such as Pt as a catalytic electrode material.3−5 Because Pt electrodes are often used for both half-reactions of the fuel cell (H2 oxidation and O2 reduction), the high costs of these metals and limited availability present significant problems for large-scale use. Of course, this is true for a multitude of catalyzed processes, and, as a result, huge efforts have been made to find inexpensive and abundant alternatives to precious metals.6

The majority of molecular electrocatalysts for H2 oxidation or production have taken inspiration from the hydrogenase enzymes that are found in nature.7−9 The active site of hydrogenase enzymes features a coordinatively unsaturated [FeFe] or [NiFe] metal center with pendant Lewis base groups in close proximity. These enzymes are able to overcome the high energy cost that is required to heterolytically cleave H2 (318.0 kJ mol–1 in MeCN)10,11 by virtue of the strong hydricity of the metal center and the strong proton acceptor ability of the pendant base. Several groups, notably DuBois and co-workers, have reported bioinspired molecular electrocatalysts for H2 oxidation using nickel12−14 and iron15−17 metals that mimic the role of hydrogenases. Rauchfuss and co-workers took an alternative approach to H2 oxidation electrocatalysis, using unsaturated iridium complexes with redox-active noninnocent amidophenolate ligands.18,19 They were able to induce Lewis acidity on the metal center through a ligand-centered oxidation, allowing the formation of a H2 adduct that is susceptible to deprotonation by a weakly coordinating base. All of these approaches still use metal-containing catalysts, and there are a greater number of literature reports that focus on biomimetic electrocatalysts for the reverse process, H2 production via proton reduction, than for H2 oxidation.9 The greatest challenges in developing H2 energy technologies still remain, to find systems that are catalytic in terms of hydrogen bond cleavage, that operate at low overpotentials (i.e., that are “electrocatalytic”), that are metal-free and/or employ inexpensive, readily available electrode materials such as carbon, and that are facile and economic to synthesize.

In this Article, we build on our recent studies of the electrochemistry of electron-deficient Lewis acid boranes,20−22 and introduce a new approach that combines classical frustrated Lewis pair (FLP) chemistry to “pre-activate” H2 with nonaqueous electrochemical oxidation of the resulting borohydride. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that FLPs have been directly used for the electrochemical activation of small molecules. Aqueous-phase borohydride ([BH4]−) electrooxidation has been reviewed extensively because of its potential for fuel cell applications;3−5 however, in this respect, the field has so far been devoid of nonaqueous applications. Since the pioneering work of Stephan’s group in 2006,23 research involving FLP chemistry has grown rapidly. The “unquenched” reactivity, arising from a suitable combination of a sterically bulky Lewis acid and a Lewis base, has been shown to heterolytically cleave H2 resulting in a hydride adduct of the Lewis acid and a protonated Lewis base.6,23−28 Boranes are typically, but not exclusively, employed as the Lewis acid component.26,27,29−35 Following the heterolytic cleavage of H2, using an FLP system, the majority of literature reports focus on delivering the resulting hydride via heterolytic B–H bond cleavage to activate/reduce other small molecules such as imines, enamines, nitriles,36,37 and even CO2.38,39 The only prior report that indirectly combines electrochemistry with FLP systems, that we are aware of, is by Stephan and co-workers, who used mono- and bis-ferrocenylphosphines in an FLP system, to observe the quasi-reversible oxidation of the ferrocene redox “label” and the reduction of the proton on the phosphonium moiety.40

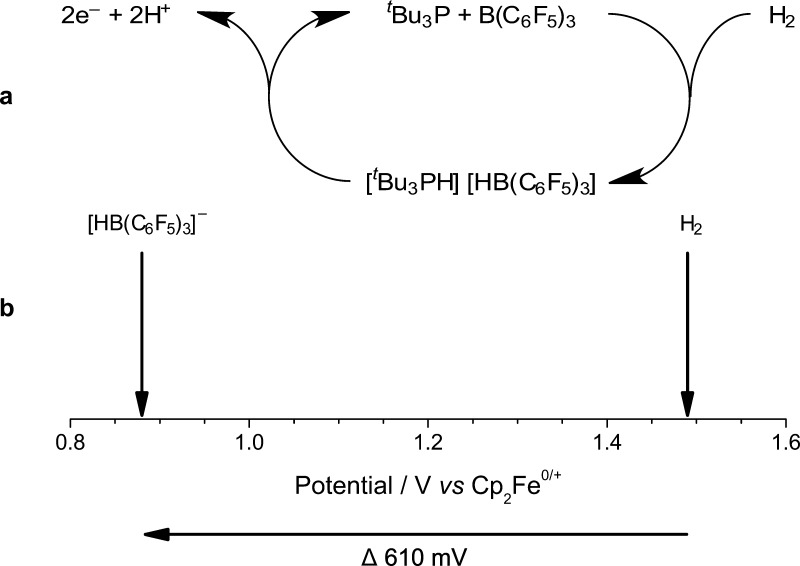

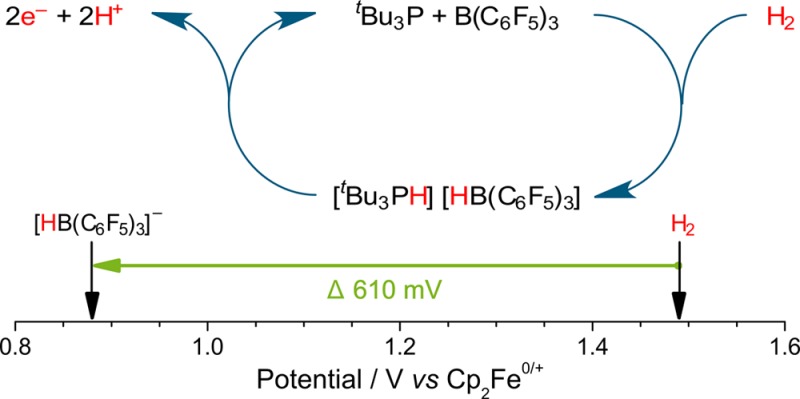

We begin by exploring the electrochemical properties of Stephan’s paradigm tBu3P/B(C6F5)3 FLP system29 and seek to use this approach to demonstrate the conversion of H2 into two protons and two electrons (Figure 1a). After elucidating the kinetic and mechanistic electrochemical behavior of this classical FLP system, we report that our approach reduces the oxidation potential of H2 in nonaqueous solvents by 610 mV (117.7 kJ mol–1) on carbon electrodes, a significant and large reduction in the required energetic driving force (Figure 1b). This new route to H2 oxidation is metal-free, operating on inexpensive, ubiquitous, carbon electrodes. While this initial finding proffers a significant enabling step toward economically viable energy technologies, we can also identify some areas for improvement in this pioneering study of a classical FLP system. Fortunately, FLPs are versatile and inherently tunable systems, with evermore-improved H2-activating FLPs reported apace. It is envisaged that the introduction of our innovative electrochemical frustrated Lewis pair approach, herein, will open new avenues to researchers for further development in small molecule activation and clean energy technologies.

Figure 1.

Proposed electrooxidation of the H2-activated tBu3P/B(C6F5)3 frustrated Lewis pair (FLP) results in (a) the generation of two protons and two electrons, and (b) an effective diminution in the potential required for H2 oxidation by 610 mV (117.7 kJ mol–1) in CH2Cl2.

Results and Discussion

Initial Electrochemical Studies

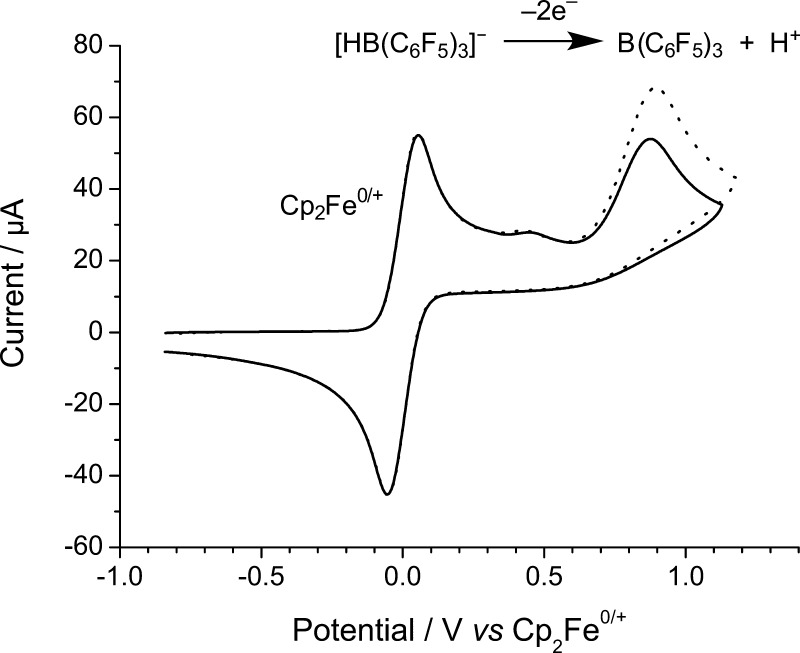

An authentic sample of [nBu4N][HB(C6F5)3] ([nBu4N]1), containing the hydridic component (1–) of the FLP H2-cleavage step, was prepared and its structure established by X-ray crystallography and spectroscopic methods (see Supporting Information sections S1.2, S2, and S3). The authentic borohydride sample allowed a detailed electrochemical study into the redox behavior of 1– to be undertaken. The direct voltammetric oxidation of [nBu4N]1, at varying concentrations, was performed at a macrodisk glassy carbon electrode (GCE) using cyclic voltammetry (Figures 2 and 3).

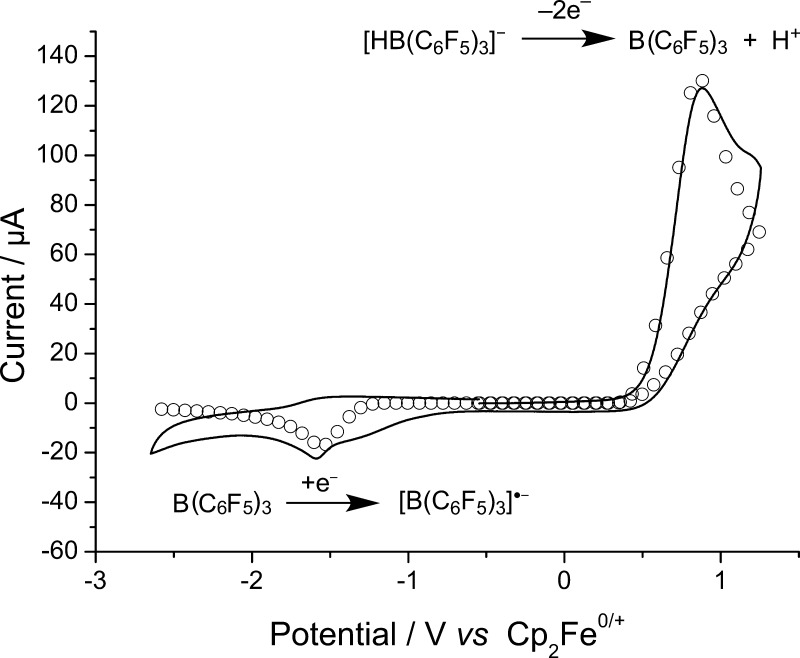

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 4.9 mM solution of [nBu4N]1 in CH2Cl2 recorded at voltage scan rates of 1000 mV s–1 over the full scan range on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Solid lines are experimental data; “○” are best fit simulated data. The oxidation wave corresponds to the oxidation of 1–, while the reduction wave corresponds to reduction of regenerated B(C6F5)3.21,22

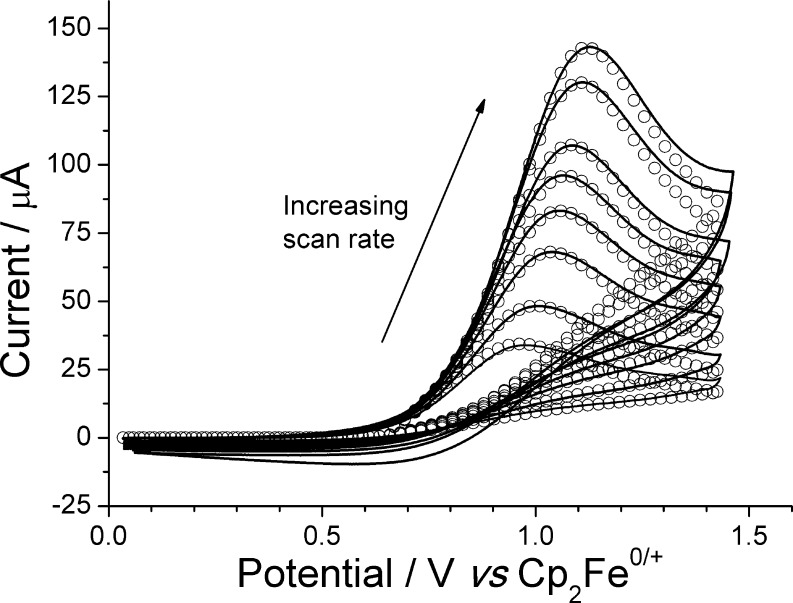

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 4.9 mM solution of [nBu4N]1 in CH2Cl2 recorded at voltage scan rates of 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 750, and 1000 mV s–1 on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Solid lines are experimental data; “○” are best fit simulated data (see text).

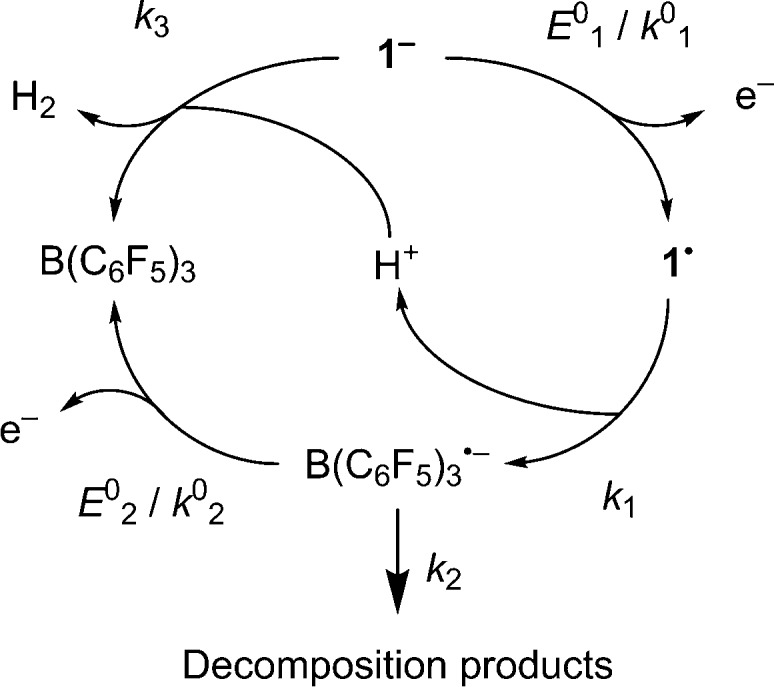

A weakly coordinating electrolyte system comprising 0.05 M [nBu4N][B(C6F5)4] in CH2Cl2 was selected for all electrochemical studies to minimize the decomposition of B(C6F5)3.20,41 On sweeping the potential anodically at a scan rate of 100 mV s–1, an oxidative wave was initially observed with a peak potential of (Ep) +0.88 ± 0.01 V vs Cp2Fe0/+, and no corresponding (quasi-reversible) reduction peak was observed upon reversing the scan direction. However, a small irreversible reduction wave was observed at −1.59 V vs Cp2Fe0/+ (Figure 2) that we assign to the reduction of some catalytically regenerated parent Lewis acid, B(C6F5)3, from our previous studies.21,22 The small size of this reduction wave is likely as a result of subsequent protonolysis of the parent B(C6F5)3 (see below). The observed voltammetry can be explained by the mechanism proposed in Figure 4, which is supported by a good fit between simulation and experiment (Figures 2 and 3) and detailed chemical and density functional theory (DFT) studies described below. The globally optimized parameters describing the oxidation of 1– were obtained from digital simulation of the CVs and are given in Table 1, while the parameters describing the reduction of B(C6F5)3 are taken from our previous work.21

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism and associated thermodynamic and kinetic parameters used in simulation of the voltammetric oxidation of 1– at a GCE (standard reduction potential, E0/V; standard electron transfer rate constant, k0/cm s–1; chemical rate constant, k/s–1).

Table 1. Globally Optimized Best-Fit Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters Obtained from Digital Simulation of Voltammetric Data for [nBu4N]1 at a GCE, Following the Mechanism Proposed in Figure 4.

| redox parameters |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| redox process | E0/V vs Cp2Fe0/+ | k0/10–3 cm s–1 | charge transfer coefficient | |

| +1.13 ± 0.05 | 13 ± 2 | 0.74 ± 0.1 | ||

| –1.79 ± 0.01a | 1.3 ± 0.3a | 0.50 ± 0.05a | ||

| chemical step | rate constant | |

|---|---|---|

| k1 > 1 × 1013 s–1 | ||

| k2 > 6.1 s–1a | ||

| k3 = (1.50 ± 0.25) × 107 M–1 s–1 |

Parameters taken from our previous studies of B(C6F5)3.21

Stoichiometric Reactions

When [nBu4N]1 is subjected to chemical oxidation using a stoichiometric amount of the single-electron oxidant [NO][PF6] in CH2Cl2, effervescence is observed. Analysis of the reaction mixture headspace using gas chromatography with a thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD) revealed that H2 gas was evolved.

Two mechanisms for H2 production are possible: (i) the reaction of electrogenerated H+ with the parent 1–, as we propose (Figure 4), or (ii) by a reaction between transient [(C6F5)3BH]• (1•) intermediates acting as H• donors. To exclude the possibility of the latter pathway, we conducted a control experiment using an authentic H•-donor, nBu3SnH, which was mixed with 4-bromobenzophenone in equimolar quantities in a sealed NMR tube and allowed to react under UV light. 1H NMR characterization of the products revealed the formation of benzophenone via the radical dehalogenation of 4-bromobenzophenone by H•. However, when [nBu4N]1 is stoichiometrically oxidized in the presence of [NO][PF6] and an equimolar amount of 4-bromobenzophenone, the latter is recovered in quantitative yield by NMR; no benzophenone is detected in the reaction mixture. Furthermore, effervescence is observed when 1 and a stoichiometric amount of Jutzi’s strong oxonium acid, [H(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4],42 are combined in CH2Cl2. H2 gas is once again detected in the reaction headspace, supporting the proposed proton-mediated H2 evolution mechanism. Note that in either case 11B NMR characterization of the product mixture reveals a number of peaks in the range −0.5 to −7.0 ppm consistent with our previous characterization of the complex products of B(C6F5)3•– decomposition (such as [(C6F5)3BCl]−, [(C6F5)2BCl2]−, [(C6F5)2BHCl]−, and [(C6F5)3BH]− and F– abstraction products from the [PF6]− anion in the former case; see ref (21) for details).21

Conclusively, when a sample of deuterated [nBu4N][DB(C6F5)3] ([nBu4N]1D) is subjected to bulk electrolytic oxidation at a glassy carbon electrode in the presence of tBu3P, an intense triplet resonance is seen in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum at 59.6 ppm (J = 65.8 Hz), which corresponds to [tBu3P–D]+. Because the only possible source of D+ is from the oxidation of 1D–, this strongly supports the proposed mechanism in Figure 4, wherein B–D/B–H bond cleavage in 1D• results in the formation of a deuteron/proton, respectively. Further support for the proposed mechanism is obtained from DFT computational calculations (Supporting Information section S5). The calculated bond energies for parent 1– and 1• reveal that bond scission is significantly enhanced upon electrooxidation.

In Situ Electrochemical Studies during the Heterolytic Cleavage of H2 by a Frustrated Lewis Pair

With a detailed understanding of the redox chemistry of 1–, we proceeded toward in situ electrochemical studies of the archetypal tBu3P/B(C6F5)3 system during the FLP cleavage of H2. The kinetics of heterolytic H2 cleavage by this FLP system are much slower than the rate of electrooxidation when monitored using 11B, 19F, and 31P NMR spectroscopy (see Supporting Information Figures S8–10). The heterolytic cleavage of H2 by the FLP was complete after 12 h, but even within 1 h evidence of H2 cleavage by the FLP could be observed in the NMR spectra. Figure 5 shows the resulting voltammetry recorded after a 1:1 solution of tBu3P:B(C6F5)3 (containing ferrocene as an internal reference) was sparged with H2 gas for 1 h.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammogram of a 5 mM solution of tBu3P and B(C6F5)3 in CH2Cl2 solution, at a GCE, after being exposed to a 1 h sparge with H2 (black line). Addition of authentic [nBu4N]1 (dotted line) to the sample confirms that the observed oxidation wave corresponds to the H2-activated product. The cyclic voltammograms were taken in the presence of a Cp2Fe internal reference at a voltage scan rate of 100 mV s–1.

Reassuringly, we observe the characteristic oxidation wave of 1–, which is identical to that of [nBu4N]1. Confirmation of this was shown by a proportional increase in the oxidation current at +0.88 V vs Cp2Fe0/+ when the solution was spiked with an authentic sample of [nBu4N]1 (Figure 5). H2 is itself oxidized sluggishly, with a broad, ill-defined wave at ca. +1.49 V vs Cp2Fe0/+ in CH2Cl2 on a glassy carbon electrode (see Supporting Information Figure S13). Hence, by employing combined electrochemical FLP approach, the oxidation of H2 now occurs with a ca. 610 mV (117.7 kJ mol–1) diminution in the required driving force. Note that [tBu3PH]+ is not redox active at the potentials studied. However, some oxidation of unreacted tBu3P is apparent as a small oxidation wave at +0.44 V vs Cp2Fe0/+.

To investigate whether this electrochemical FLP system can be recycled, that is, is catalytic in the Lewis acid, the following experiments were performed: A CH2Cl2 solution containing a 5 mM 1:1 mixture of B(C6F5)3:tBu3P and 0.1 M [nBu4N][B(C6F5)4] electrolyte was sealed under an atmosphere of H2 for 12 h at room temperature to ensure that the FLP heterolytic cleavage of H2 was complete. This solution was then subjected to bulk electrolysis using a glassy carbon felt electrode until all of the 1– had been oxidized. The solution was again sealed under H2 with the addition of another equimolar amount of tBu3P, for a further 12 h, and the electrolysis was repeated. Disappointingly, upon a second and third electrolytic cycle, no evidence for the regeneration of the parent borane, B(C6F5), and subsequent reformation of 1– could be observed, consistent with the 11B NMR characterization of the products of chemical oxidation of 1– and the fact that we only observe a small reductive peak corresponding to B(C6F5)3 upon cyclic voltammetric oxidation of [nBu4N]1, described above. Clearly, the B(C6F5)3•– intermediate produced upon oxidation undergoes significant side reactions with the solvent, and any B(C6F5)3 generated is susceptible to protonolysis by the H+, which is liberated alongside the formation of B(C6F5)3•–. Note that “buffering” the electrolyte using excess phosphine Lewis base to prevent unwanted protonolysis reactions is not possible in this system as the Lewis base is itself redox active at potentials similar to that of 1–.

Given that this is the first study of the electrochemistry of FLPs toward H2 activation, and choosing the archetypal B(C6F5)3/tBu3P seems a logical starting point for these investigations, it is perhaps not surprising that this system is not optimal. However, these findings are important as they demonstrate that the electrochemical FLP approach has genuine promise for metal-free H2 oxidation at significantly lower oxidative potentials, with obvious synthetic and energy applications. This study also allows us to immediately identify areas for future improvement in electrochemical FLP systems: (i) Competing protonation of 1– regenerates H2 and reduces the overall efficiency of the process (although the H2 may be subsequently recycled in future systems), but protonolysis also leads to unwanted decomposition of the Lewis acidic borane. Lewis acids that are resistant to protonolysis are required. (ii) The B(C6F5)3•– radical anion intermediate generated during oxidation of the parent borohydride is susceptible to reaction with the solvent, again preventing the system from being recycled. Steric and/or electronic protection of any radical anion intermediates is required. (iii) The kinetics of H2 splitting by the FLP are rate determining versus rapid electron transfer in this classical FLP system. Fortunately, improved combinations of novel Lewis acids and bases continue to develop rapidly in conventional FLP chemistry. The inherent “tuneability” of FLP properties thus offers enormous potential for the further development of electrochemical FLP systems, and promising candidates that may overcome all of these obstacles are currently under investigation.

Conclusions

We have characterized the complex nonaqueous redox chemistry of 1– for the first time. By combining FLP preactivation of H2 with electrochemical oxidation of the resultant Lewis acid hydride, we have reduced the potential that is required for nonaqueous H2 oxidation by 610 mV (117.7 kJ mol–1) at readily available carbon electrodes. This is a significant energy reduction without the use of metals (precious or otherwise), which opens hitherto unexplored routes to the development of economically viable H2-based energy technologies and H2-activation chemistries. We have also demonstrated that our electrochemical FLP approach is possible with in situ H2 activation using a classical FLP system. Our work has identified specific areas for future development to further extend the scope and possibilities of this electrochemical FLP chemistry. Patent protection for the intellectual property described herein has been sought.

Experimental Details

General Considerations

Commercially available reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK) and used without further purification unless stated otherwise. All synthetic reactions and manipulations were performed under a rigorously dry N2 atmosphere (BOC Gases) using standard Schlenk-line techniques on a dual manifold vacuum/inert gas line or either a Saffron or an MBraun glovebox. All glassware was flame-dried under vacuum before use. Anhydrous solvents were dried via distillation over appropriate drying agents. All solvents were sparged with nitrogen gas to remove any trace of dissolved oxygen and stored in ampules over activated 4 Å molecular sieves. nBu4NCl and NOPF6 were purchased from Alfa Aesar. nBu4NCl was recrystallized from acetone prior to use. H2 gas (99.995%) was purchased from BOC gases and passed through drying columns containing P4O10 and 4 Å molecular sieves. D2 gas was generated in situ from the reaction of Na with degassed D2O (99.9%, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc.); it was passed through a drying column containing P4O10. Deuterated NMR solvents ([D6]DMSO, 99.9%; CDCl3, 99.8%; C6D6, 99.5%) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. and were dried over P4O10, degassed using a triple freeze–pump–thaw cycle, and stored over activated 4 Å molecular sieves. B(C6F5)3,43 [nBu4N][B(C6F5)4],44,45 [H(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4],42 and tBu3P46 were prepared according to literature methods. [TMP–D][D–B(C6F5)3] was prepared using an adapted literature method,47 which is detailed in the Supporting Information. Synthesis and characterization of compounds [nBu4N]1 and [nBu4N]1D are detailed in the Supporting Information.

NMR spectra were recorded using either a Bruker Avance DPX-300 MHz or a Bruker Avance DPX-500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm and are referenced relative to appropriate standards: 19F (CFCl3); 11B (Et2O·BF3); 31P (85% H3PO4). IR spectra were recorded using a PerkinElmer μ-ATR Spectrum II spectrometer. Sample headspace analysis was performed using a PerkinElmer Clarus 580 gas chromatograph coupled with a thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD). Retention time for H2 gas was calibrated using a standard sample. Electrochemical measurements were performed in CH2Cl2 containing 0.05–0.10 M [nBu4N][B(C6F5)4] as a weakly coordinating electrolyte salt using either a PGSTAT 302N or a PGSTAT 30 computer-controlled potentiostat (Autolab, Utrecht, The Netherlands) in an inert atmosphere three-electrode cell that was designed in-house (see the Supporting Information for further details). Digital simulation of voltammetric data was performed using the commercially available DigiElch Pro software package (v.7). Diffraction intensities of [nBu4N]1 were recorded using a AFC12 Kappa 3 CCD diffractometer (at the EPSRC UK National Crystallography Service) equipped with Mo Kα radiation and confocal mirrors monochromator (for further details, see the Supporting Information).

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the ERC Grant Agreement no. 307061 (ERC-St-G-PiHOMER). We thank the EPSRC UK National Crystallography Service at the University of Southampton for the collection of the crystallographic data for [nBu4N]1.48 G.G.W. and A.E.A. thank the Royal Society for financial support via University Research Fellowships. E.J.L. thanks the EPSRC for financial support via a DTA studentship under the grant code EP/J500409.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic details, NMR characterization, X-ray crystallography, electrochemistry, and DFT calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dunn S. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.; Sverdrup G.; Mann M. K.; Maness P.-C.; Kroposki B.; Ghirardi M.; Evans R. J.; Blake D. Int. J. Energy Res. 2008, 32, 379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Santos D. M. F.; Sequeira C. A. C. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3980–4001. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Jiménez I.; Ponce de León C.; Shah A. A.; Walsh F. C. J. Power Sources 2012, 219, 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Choudhury N. A.; Sahai Y. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Catalysis Without Precious Metals; Bullock R. M., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vignais P. M.; Billoud B. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4206–4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tard C.; Pickett C. J. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2245–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois D. L.; Bullock R. M. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C. J.; Miedaner A.; Ellis W. W.; DuBois D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayner D. D.; Parker V. D. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y.; Bullock R. M.; Shaw W. J.; Twamley B.; Fraze K.; Rakowski DuBois M.; DuBois D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5935–5945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff A. L.; Artero V.; Jousselme B.; Tran P. D.; Guillet N.; Métayé R.; Fihri A.; Palacin S.; Fontecave M. Science 2009, 326, 1384–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y.; Chen S.; Dougherty W. G.; Kassel W. S.; Bullock R. M.; DuBois D. L.; Raugei S.; Rousseau R.; Dupuis M.; Rakowski DuBois M. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 8618–8620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara J. M.; Rauchfuss T. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8098–8101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara J. M.; Rauchfuss T. B. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.; DuBois D. L.; Bullock R. M. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringenberg M. R.; Kokatam S. L.; Heiden Z. M.; Rauchfuss T. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 788–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringenberg M. R.; Nilges M. J.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Wilson S. R. Organometallics 2010, 29, 1956–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley A. E.; Herrington T. J.; Wildgoose G. G.; Zaher H.; Thompson A. L.; Rees N. H.; Kraemer T.; O’Hare D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14727–14740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E. J.; Oganesyan V. S.; Wildgoose G. G.; Ashley A. E. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings S. A.; Iimura M.; Harlan C. J.; Kwaan R. J.; Trieu I. V.; Norton J. R.; Bridgewater B. M.; Jaekle F.; Sundararaman A.; Tilset M. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Welch G. C.; Juan R. R. S.; Masuda J. D.; Stephan D. W. Science 2006, 314, 1124–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 5740–5746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Dalton Trans. 2009, 3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W.; Erker G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 46–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erker G. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 7475–7483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G. C.; Stephan D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1880–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Blacque O.; Fox T.; Berke H. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Cheng Z.; Chen Z.; Weng L.; Li Z. H.; Wang H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12227–12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington T. J.; Thom A. J. W.; White A. J. P.; Ashley A. E. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 9019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss T.; Mahdi T.; Otten E.; Fröhlich R.; Kehr G.; Stephan D. W.; Erker G. Organometallics 2012, 31, 2367–2378. [Google Scholar]

- Binding S. C.; Zaher H.; Chadwick F. M.; O’Hare D. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 9061–9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis A. L.; Binding S. C.; Zaher H.; Arnold T. A. Q.; Buffet J.-C.; O’Hare D. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. A.; Jurca T.; Stephan D. W. Chem. Commun. 2008, 1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W.; Greenberg S.; Graham T. W.; Chase P.; Hastie J. J.; Geier S. J.; Farrell J. M.; Brown C. C.; Heiden Z. M.; Welch G. C.; Ullrich M. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12338–12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran S. D.; Tronic T. A.; Kaminsky W.; Michael Heinekey D.; Mayer J. M. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 369, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley A. E.; Thompson A. L.; O’Hare D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9839–9843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A.; Lough A. J.; Stephan D. W. Chem. Commun. 2009, 1118–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger W. E.; Barrière F. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutzi P.; Müller C.; Stammler A.; Stammler H.-G. Organometallics 2000, 19, 1442–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster S. J. ChemSpider Synthetic Pages 2003, 10.1039/SP215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E.; Hughes D. L.; Lancaster S. J. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- LeSuer R. J.; Buttolph C.; Geiger W. E. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 6395–6401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R. C. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1985, 330–331. [Google Scholar]

- Sumerin V.; Schulz F.; Nieger M.; Leskelä M.; Repo T.; Rieger B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6001–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A.; Coles S. Chem. Sci. 2012, 683. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.