Abstract

Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 is a filamentous, heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium that has served as a model organism, with an extensive literature extending over 40 years. The strain has three distinct nitrogenases that function under different environmental conditions and is capable of photoautotrophic growth in the light and true heterotrophic growth in the dark using fructose as both carbon and energy source. While this strain was first isolated in 1964 in Mississippi and named Anabaena flos-aquae MSU A-37, it clusters phylogenetically with cyanobacteria of the genus Nostoc. The strain is a moderate thermophile, growing well at approximately 40° C. Here we provide some additional characteristics of the strain, and an analysis of the complete genome sequence.

Introduction

Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 (=IUCC 1444 = PCC 7937) is a semi-thermophilic, filamentous, heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium. Heterocysts, which are specialized cells that form in a semi-regular pattern in the filament, are the sites of nitrogen fixation in cells grown in an oxic environment. A. variabilis ATCC 29413 was first isolated as a freshwater strain in 1964 in Mississippi by R.G. Tischer, who called the strain Anabaena flos-aquae A-37 [1]. He was primarily interested in the extracellular polysaccharide produced by this strain [2-4], which was subsequently called Anabaena variabilis by Healey in 1973 [5]. It was characterized in more detail by several labs in the 1960’s and 1970’s [6-8]. In particular, the early work by Wolk on this strain led to its becoming a model strain for cyanobacterial physiology, nitrogen fixation and heterocyst formation [9-13]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for A. variabilis ATCC 29413 together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

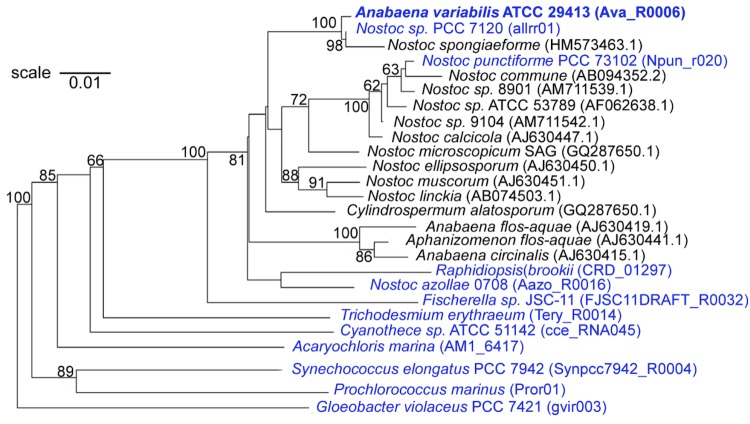

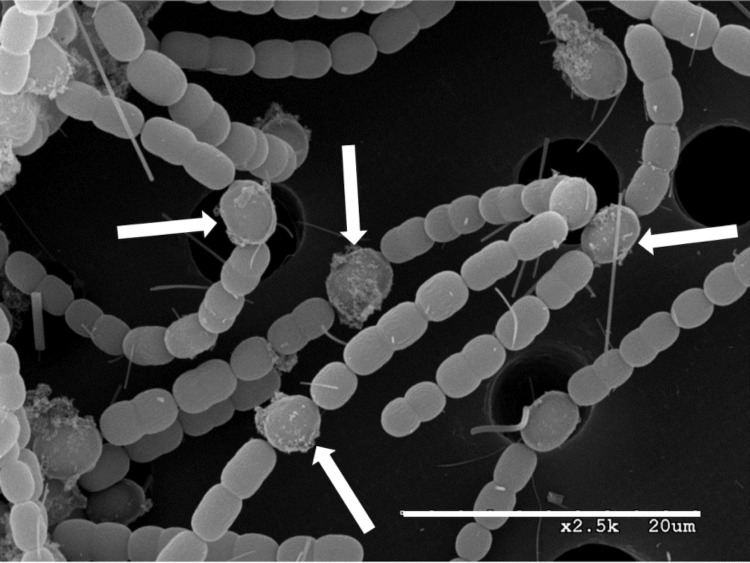

The general characteristics of A. variabilis are summarized in Table 1 and its phylogeny is shown in Figure 1. Vegetative cells of A. variabilis are oblong, 3-5 µm in length, have a Gram-negative cell wall structure, are normally non-motile, and form long filaments. Under conditions of nitrogen deprivation, certain vegetative cells differentiate heterocysts, which are the sites of aerobic nitrogen fixation (reviewed in [19,28,29]). Heterocysts, which comprise 5-10% of the cells in a filament, are terminally differentiated cells that form in a semi-regular pattern in the filament (Figure 2). Vegetative cells of A. variabilis can also differentiate into akinetes, which are spore-like cells that survive environmental stress [30]. Nitrogen stress may also induce the formation of motile filaments called hormogonia in A. variabilis [19]. In other cyanobacteria hormogonia are required for the establishment of symbiotic associations with plants [31]. A. variabilis has oxygen-evolving photosynthesis; however, it is also capable of photoheterotrophic growth and chemoheterotrophic growth in the dark using fructose [23,32-34]. The strain cannot ferment; hence, it does not grow anaerobically in the dark with fructose. The genome sequence revealed the ABC-type fructose transport genes that were subsequently shown to be required for heterotrophic growth of the strain [32].

Table 1. Classification and general features of A. variabilis ATCC 9413 according to the MIGS recommendations [14].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [15] | |

| Phylum Cyanobacteria | |||

| Class Nostocophycidae | |||

| Order Nostocales | |||

| Family Nostocaceae | |||

| Genus Anabaena | TAS [16] | ||

| Species Anabaena variabilis | |||

| Gram stain | Negative | TAS [17] | |

| Cell shape | Ovoid cells in filaments | TAS [18] | |

| Motility | Hormogonia | TAS [19] | |

| Sporulation | Akinetes | TAS [20] | |

| Temperature range | 20 – 40°C | TAS [21] | |

| Optimum temperature | 35°C | TAS [22] | |

| MIGS-22 | Relationship to Oxygen | Aerobic | NAS |

| Carbon source | Autotroph, heterotroph | TAS [23] | |

| Energy source | Phototroph, heterotroph | TAS [23] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat (EnvO) | Fresh water | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | 1.5% (maximum) | TAS [24] |

| MIGS-10 | Extrachromosomal elements | 4 | TAS (this report) |

| MIGS-11 | Estimated Size | 7.1 Mb | TAS (this report) |

| MIGS-14 | Known Pathogenicity | None | NAS |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic Relationship | Free living; symbiotic | IED |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic Location | Isolated Mississippi, 1964 | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [25]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a living isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 1.

16S phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 relative to other cyanobacterial strains. Strains in blue have been sequenced and the 16S rRNA IMG locus tag is shown in parentheses after the strain. GenBank accession numbers are provided for 16S rRNA genes in strains that do not have a complete genome sequence (shown in black). The tree was made with sequences aligned by the RDP aligner, with the Jukes-Cantor corrected distance model, to construct a distance matrix based on alignment model positions, without alignment inserts, and uses a minimum comparable position of 200. The tree is built with RDP Tree Builder, which uses Weighbor [26] with an alphabet size of 4 and length size of 1,000. Bootstrapping (100 times) was used to generate a majority consensus tree [27]. Bootstrap values over 60 are shown. Gleothece violaceus PCC 7421 was used as the outgroup.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of filaments of A. variabilis. Heterocysts are the larger cells with extracellular polysaccharide visible (indicated by the white arrows). Slender fibers are an artifact caused by the use of a glass fiber filter to support the cells on the membrane filter during washing. The length of the line is 20 μm.

A. variabilis is a well-established model organism for heterocyst formation [35,36], nitrogen fixation [21,37,38], hydrogen production [39,40], photosynthesis [41-43], and heterotrophic cyanobacterial growth [9,32,44]. It is unique among the well-characterized cyanobacteria in that it has three sets of genes that encode distinct nitrogenases [19,37,38,45-48]. One is the conventional, heterocyst-specific Mo-nitrogenase, the second is another Mo-nitrogenase that functions only under anoxic conditions in vegetative cells and heterocysts, while the third is a V-nitrogenase that is also heterocyst specific. These nitrogenases are expressed under distinct physiological conditions so that only one nitrogenase is generally functional [19]. The genome sequence has revealed a large 41-kb island of genes that all appear to be involved in synthesis and regulation of the V-nitrogenase, including the genes for the first vanadate transport system to be characterized in any bacterium [49]. The V-nitrogenase of A. variabilis has been exploited for its ability to make large amounts of hydrogen as a potential source of alternative energy production [39,40].

Chemotaxonomy

The Gram-negative cyanobacterial cell wall has not been well characterized; however, it typically contains lipopolysaccharide. In A. variabilis the O antigen contains L-acofriose, L-rhamnose, D-mannose, D-glucose, and D-galactose [50]. The cell envelope of the heterocyst differs from vegetative cells in that it also contains an inner laminated glycolipid layer and an outer fibrous, homogeneous polysaccharide layer. In A. variabilis the polysaccharide layer comprises a 1,3-linked backbone of glucosyl and mannosyl residues with terminal xylosyl and galactosyl residues. The side branches comprise glucosyl residues having a terminal arabinosyl residue. The inner heterocyst cell wall of almost all strains of Anabaena and Nostoc consists of a glycolipid comprising 1-(O-hexose)-3,25-hexacosanediol and 1-(O-hexose)-3-keto-25-hexacosanol [51,52]. The lipids of most cyanobacteria comprise monogalactosyldiacylglycerols, digalactosyldiacylglycerols, sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerols and phosphatidylglycerols [53].

In A. variabilis the primary products of lipid biosynthesis are 1-stearoyl-2-palmitoyl species of monoglucosyl diacylglycerol, phosphatidylglycerol and sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol; however, the degree of saturation of the fatty acids in the lipids depends on the growth temperature [54-56]

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing because of its 50-year long history as a model organism for studies on many aspects cyanobacterial metabolism including photosynthesis, nitrogen fixation, hydrogen production, and heterotrophic growth. The genome project is deposited in the Genome On Line Database (Gc00299) and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Project Information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished - < one error per 50 kb |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 3-kb pUC18c; 9-kbpMCL200; 40-kb pCC1Fos |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Sanger; ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 11× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Phred/Phrap/Consed |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Critica, Glimmer |

| Genbank ID | 240292 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 17, 2005 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc00299 | |

| Project relevance | Hydrogen production; nitrogen fixation |

Strain history

The strain was first isolated by R.G. Tischer, in 1964 in Mississippi, who called it Anabaena flos-aquae MSU A-3 7 [1]. It was submitted to the Indiana University Culture Collection (Anabaena flos-aquae IUCC 1444) and was then submitted by C.P Wolk as Anabaena variabilis to ATCC in 1976 (Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413). The phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) reveals that the strain clusters with cyanobacteria in the genus Nostoc, which is consistent with the fact that it produces hormogonia [19], and not with the cluster of Anabaena/Aphanizomenon, suggests that the strain was incorrectly named.

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

An axenic culture of A. variabilis ATCC 29413 was grown photoautotrophically in one L of an eight-fold dilution of the medium of Allen and Arnon (AA/8) [57], supplemented 5.0 mM NaNO3 at 30°C with illumination at 50-80 μEinsteins m-2 s-1 to an OD720 of about 0.3. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, frozen and then lysed by a combination of crushing the frozen pellet with a very cold mortar and pestle, and then treating the frozen powder with lysozyme (3.0 mg/ml)/proteinase K (1 mg/ml) in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM EDTA pH 8.0 buffer at 37°C for 30 min. This was followed by purification of the DNA using a Qiagen genomic DNA kit. The DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, spooled, and then dissolved in 10 mM Tris, 1.0 mM EDTA pH 8.0 buffer. The purity, quality and size of the bulk gDNA preparation were assessed by JGI according to DOE-JGI guidelines.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Sequencing and assembly

Sanger sequencing was done using a whole-genome shotgun approach with three plasmid libraries. A pUC18c library with 3-kb inserts generated 39.64 Mb of sequence. A pMCL200 library with 9-kb inserts produced 35.16 Mb of sequence, and a fosmid(pCC1Fos CopyControl fosmid library production kit; Epicentre, Madison, WI) library with 40-kb inserts yielded 5.83 Mb of sequence. Together, all libraries provided greater than 11.0× coverage of the genome. The plasmid inserts were made with sheared DNA that was blunt-end repaired and then size separated by gel electrophoresis. Sequencing from both ends of the plasmid inserts was done using dye terminators on ABI3730 sequencers. Details on the cloning and sequencing procedures are available from JGI [58]. Project information is summarized in Table 2.

The Phred, Phrap, and Consed software package was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment [59] Repeat sequences were resolved with Dupfinisher [60]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom priming, or PCR amplification. This genome was curated to close all gaps with greater than 98% coverage of at least two independent clones. Each base pair has a minimum q (quality) value of 30 and the total error rate is less than one per 50,000.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using two gene modeling programs, Glimmer [61] and Critica [62] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline [63].The two sets of gene calls were combined using Critica as the preferred start call for genes with the same stop codon. Genes with less than 80 amino acids that were predicted by only one of the gene callers and had no Blast hit in the KEGG database at 1e-5 were deleted. This was followed by a round of manual curation to eliminate obvious overlaps. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [64], TMHMM [65], and signal [66].

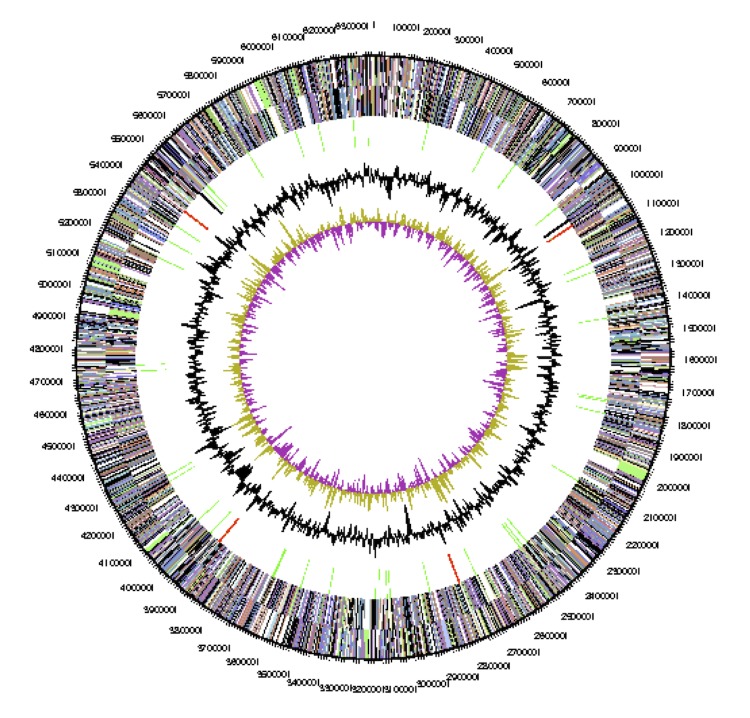

Genome properties

The genome of A. variabilis, with a total of 7.1 Mbp (7,105,752 bp), has 41.4% GC (Table 4). There is a single large circular chromosome (6.36 Mbp) (Figure 3), three circular plasmids and one linear DNA element (Table 3). Plasmid A is circular with 366,354 bp and 41% GC. Plasmid B is circular with 5,762 bp and 38% GC. Plasmid C is circular with 300,758 bp and 42% GC.

Table 4. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 7,105,752 | 100 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 5,849,926 | 82.3 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,942,474 | 41.4 |

| Total genes | 5,772 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 62 | 1.0 |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,710 | 99.0 |

| Protein coding genes with function prediction | 3,079 | 53.3 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 3,431 | 59.4 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,670 | 63.6 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 4,352 | 75.4 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 873 | 15.1 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,383 | 24.0 |

| CRISPR repeats | 7 | 0.1 |

| Paralogous groups | 851 | 14.6 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome of Anabaena variabilis. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 3. Summary of genome: one chromosome, three plasmids and one linear element.

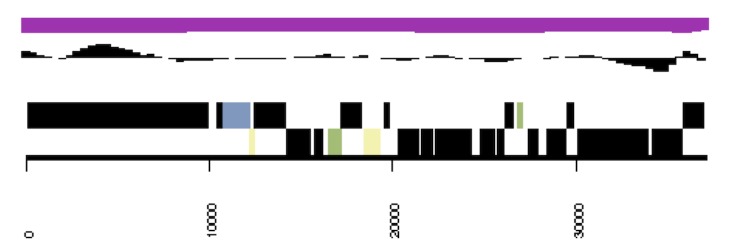

The linear incision element is 37,151 bp long with a higher GC content (46%) than the rest of the genome (Figure 4). The incision element has 40 ORFs of which only 5 have any similarity to known genes. AvaD004 has about 40% aa similarity to many proteins provisionally identified as phage terminases, which are involved in phage assembly. AvaD0022 is similar to RNA polymerase sigma factors, with 35% identity to a sigF encoded sigma factor, present in many other cyanobacteria including two copies of a similar gene of the large chromosome of A. variabilis. AvaD0026, identified as similar to site specific XerD-like recombinases shows 50-55% identity to genes present in many cyanobacteria including the B plasmid of A. variabilis and the alpha plasmid of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. AvaD0037 shows similarity to the XRE family of transcriptional regulator and 65% identity to similar proteins in three sequenced strains of the cyanobacterium Cyanothece. AvaD0015 is a histone-like DNA binding protein with about 70% identity to the HU gene present in most cyanobacteria including the gene on the large circular chromosome of A. variabilis. Many linear molecules overcome the problem of replicating the genome ends using terminal hairpins; however, there is no evidence of such repeats in this element.

Figure 4.

Graphical map of the linear incision element of Anabaena variabilis. From the bottom to the top: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), GC content, GC skew.

A total of 5,772 genes were predicted in the whole genome. Of these, 3,079 were annotated as coding for known protein functions and 62 for RNA genes (12 for rRNA and 50 for tRNA). The distribution of genes into COGs is presented in Table 4. There is considerable redundancy, with 5,710 protein coding genes belonging to 841 paralogous families in this genome.

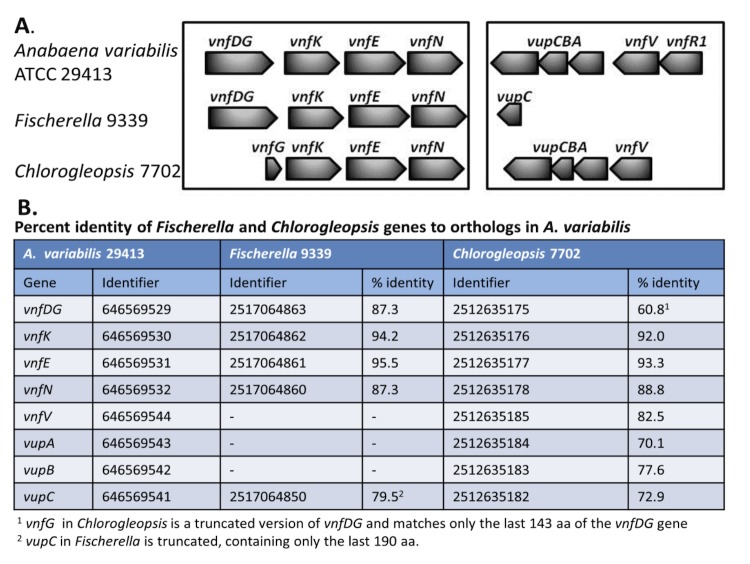

Identification of vnf genes in other cyanobacterial genomes

The V-nitrogenase is not widespread among bacteria and has, to date, been characterized in only one cyanobacterium, A. variabilis [42,49,67], [Figure 5]. Using the large number of cyanobacterial genomes now available, we searched the IMG database for orthologs for the V-nitrogenase genes (vnf) and the vanadate transport genes (vupABC) present in A. variabilis. Only two strains showed any evidence of vnf genes, Fischerella 9339 (taxon ID 2516653082) and Chlorogleopsis 7702 (taxon ID 2512564012). Fischerella 9339 has orthologs of vnfDG, vnfK, vnfE and vnfN, but is missing most of the vanadate transport genes. In contrast, Chlorogleopsis 7702 has orthologs for all three of the vanadate transport genes, and has most of the structural genes for the V-nitrogenase; however, the fused vnfDG gene is missing the vnfD portion that encodes the alpha subunit of the enzyme, which is essential for dinitrogenase activity. It will be interesting to determine whether either of these strains is capable of fixing nitrogen in the absence of Mo and in the presence of V using the V-nitrogenase.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the organization of the vnf genes for the V-nitrogenase and the vup genes for vanadate transport from A. variabilis with similar genes found in the genomes of Fischerella 9339 (taxon ID 2516653082) and Chlorogleopsis 7702 (taxon ID 2512564012), based on the genome sequences available at from the JGI data base. Gene identifiers are the Gene Object ID numbers in the IMG database. A. Graphical representation of similar genes. B. Percent identity of genes.

Conclusions

A. variabilis was one of the earliest model organisms for the study of important cellular processes such as photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation. It is unusual among cyanobacteria in that it has three nitrogenases [19], one of which, the V-nitrogenase, has been shown to be useful for hydrogen production [40], and for its ability to grow both photoautotrophically in the light and heterotrophically in the dark. The genome sequence was critical in identifying the genes for fructose transport [32] and the large island of genes important for V-nitrogenase function, including the vupABC genes for vanadate transport [49]. No other cyanobacterial genome has all the genes identified in A. variabilis that are important for growth using the V-nitrogenase, but two strains, Fischerella 9339 and Chlorogleopsis 7702, have some V-nitrogenase or vanadate transport genes. The presence of the linear genetic element shown in Fig. 4 is quite interesting, as such elements are not present in the genomes of the other Nostoc strains. It will also be interesting to determine whether this element is important to the cell and how this element replicates.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided to Teresa Thiel by National Science Foundation grant MCB-1052241. The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

References

- 1.Yoshimitsu K, Takatani N, Miura Y, Watanabe Y, Nakajima H. The role of the GAF and central domains of the transcriptional activator VnfA in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEBS J 2011; 278:3287-3297 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore BG, Tischer RG. Biosynthesis of extracellular polysaccharides by the blue-green alga Anabaena flos-aquae. Can J Microbiol 1965; 11:877-885 10.1139/m65-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tischer RG, Davis EB. The effect of various nitrogen sources upon the production of extracellular polysaccharide by the blue-green alga Anabaena flos-aquae A-37. J Exp Bot 1971; 22:546-551 10.1093/jxb/22.3.546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang WS, Tischer RG. Study of the extracellular polysaccharides produced by a blue-green alga, Anabaena flos-aquae A-37. Arch Microbiol 1973; 91:77-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healey FP. Characteristics of phosphorus deficiency in Anabaena. J Phycol 1973; 9:383-394 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bone DH. Kinetics of synthesis of nitrogenase in batch and continuous culture of Anabaena flos-aquae. Arch Microbiol 1971; 80:242-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bone DH. Relationships between phosphates and alkaline phosphatase on Anabaena flos-aquae in continous culture. Arch Microbiol 1971; 80:147-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bone DH. Nitrogenase activity and nitrogen assimilation in Anabaena flos-aquae growing in continuous culture. Arch Microbiol 1971; 80:234-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolk CP, Shaffer PW. Heterotrophic micro- and macrocultures of a nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Arch Microbiol 1976; 110:145-147 10.1007/BF00690221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currier TC, Haury JF, Wolk CP. Isolation and preliminary characterization of auxotrophs of a filamentous cyanobacterium. J Bacteriol 1977; 129:1556-1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haury JF, Wolk CP. Classes of Anabaena variabilis mutants with oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase activity. J Bacteriol 1978; 136:688-692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson RB, Wolk CP. High recovery of nitrogenase activity and of 55Fe-labeled nitrogenase in heterocysts isolated from Anabaena variabilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1978; 75:6271-6275 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeks JC, Wolk CP, Lockau W, Schilling N, Shaffer PW, Chien WS. Pathways of assimilation of [13N]N2 and 13NH4+ by cyanobacteria with and without heterocysts. J Bacteriol 1978; 134:125-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeill J, Barrie FR, Burdet HM, Demoulin V, Hawksworth DL, Marhold K, Nicolson DH, Prado J, Silva PC, Skog JE, et al International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, A.R.G. Ganter, Königstein, 2006, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoiczyk E, Hansel A. Cyanobacterial cell walls: news from an unusual prokaryotic envelope. J Bacteriol 2000; 182:1191-1199 10.1128/JB.182.5.1191-1199.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1979; 111:1-61 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiel T. Nitrogen fixation in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. In: Klipp W, Masepohl B, Gallon JR, Newton WE, editors. Genetics and Regulation of Nitrogen Fixing Bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. p 73-110. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou R, Wolk CP. Identification of an akinete marker gene in Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 2002; 184:2529-2532 10.1128/JB.184.9.2529-2532.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis EB. Nitrogen fixation by Anabaena flos-aquae A-37. Department of Microbiology, Mississippi State University.; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogg GE. The comparative physiology and biochemistry of the blue-green algae. Bacteriol Rev 1956; 20:148-165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valiente EF, Nieva M, Avendano MC, Maeso ES. Uptake and utilization of fructose by Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. Effect on respiration and photosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol 1992; 33:307-313 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niven GW, Kerby NW, Rowell P, Reed RH, Stewart WDP. The effects of salt on nitrogen-fixation and ammonium assimilation in Anabaena variabilis. Br Phycol J 1987; 22:411-416 10.1080/00071618700650471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruno WJ, Socci ND, Halpern AL. Weighted neighbor joining: a likelihood-based approach to distance-based phylogeny reconstruction. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:189-197 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, Bandela AM, Cardenas E, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35(suppl 1):D169-D172 10.1093/nar/gkl889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maldener I, Muro-Pastor AM. Cyanobacterial Heterocysts. eLS: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar K, Mella-Herrera RA, Golden JW. Cyanobacterial heterocysts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2:a000315 10.1101/cshperspect.a000315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams DG, Duggan PS. Heterocyst and akinete differentiation in cyanobacteria. New Phytol 1999; 144:3-33 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00505.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meeks JC, Elhai J. Regulation of cellular differentiation in filamentous cyanobacteria in free-living and plant-associated symbiotic growth states. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002; 66:94-121 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.94-121.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ungerer JL, Pratte BS, Thiel T. Regulation of fructose transport and its effect on fructose toxicity in Anabaena spp. J Bacteriol 2008; 190:8115-8125 10.1128/JB.00886-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang NJ, Krupp JM, Koller AL. Morphological and ultrastructural changes in vegetative cells and heterocysts of Anabaena variabilis grown with fructose. J Bacteriol 1987; 169:920-923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haury JF, Spiller H. Fructose uptake and influence on growth of and nitrogen fixation by Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 1981; 147:227-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson RB, Shaw ER, Dolan E, Ke B. A photochemically active heterocyst preparation from Anabaena variabilis. Photobiochem Photobiophys 1981; 2:79-84 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Böhme H, Schrautemeier B. Electron donation to nitrogenase in a cell-free system from heterocysts of Anabaena variabilis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1987; 891:115-120 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90002-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ungerer JL, Pratte BS, Thiel T. RNA processing of nitrogenase transcripts in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 2010; 192:3311-3320 10.1128/JB.00278-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pratte BS, Eplin K, Thiel T. Cross-functionality of nitrogenase components NifH1 and VnfH in Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 2006; 188:5806-5811 10.1128/JB.00618-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weyman PD, Pratte B, Thiel T. Hydrogen production in nitrogenase mutants in Anabaena variabilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2010; 304:55-61 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsygankov AA, Borodin VB, Rao KK, Hall DO. H2 photoproduction by batch culture of Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 and its mutant PK84 in a photobioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng 1999; 64:709-715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannan RM, Pakrasi HB. Dark heterotrophic growth conditions result in an increase in the content of photosystem II units in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. Plant Physiol 1993; 103:971-977 10.1104/pp.103.3.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nyhus KJ, Thiel T, Pakrasi HB. Targeted interruption of the psaA and psaB genes encoding the reaction-centre proteins of photosystem I in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. Mol Microbiol 1993; 9:979-988 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyhus KJ, Ikeuchi M, Inoue Y, Whitmarsh J, Pakrasi HB. Purification and characterization of the photosystem I complex from the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. J Biol Chem 1992; 267:12489-12495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen B. Fructose utilization by the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis studied using whole filaments and isolated heterocysts. Arch Microbiol 1990; 154:92-98 10.1007/BF00249184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiel T, Lyons EM, Erker JC. Characterization of genes for a second Mo-dependent nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 1997; 179:5222-5225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiel T, Lyons EM, Erker JC, Ernst A. A second nitrogenase in vegetative cells of a heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92:9358-9362 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyons EM, Thiel T. Characterization of nifB, nifS, and nifU genes in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis: NifB is required for the vanadium-dependent nitrogenase. J Bacteriol 1995; 177:1570-1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiel T. Characterization of genes for an alternative nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 1993; 175:6276-6286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pratte BS, Thiel T. High-affinity vanadate transport system in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. J Bacteriol 2006; 188:464-468 10.1128/JB.188.2.464-468.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weckesser J, Katz A, Drew G, Mayer H, Fromme I. Lipopolysaccharide containing L-acofriose in the filamentous blue-green alga Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 1974; 120:672-678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cardemil L, Wolk CP. Polysaccharides from the envelopes of heterocysts and spores of the blue-green algae Anabaena variabilis and Cylindrospermum licheniforme. J Phycol 1981; 17:234-240 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1981.tb00845.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardemil L, Wolk CP. Isolated heterocysts of Anabaena variabilis synthesize envelope polysaccharide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1981; 674:265-276 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90384-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sallal AK, Nimer NA, Radwan SS. Lipid and fatty acid composition of freshwater cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1990; 136:2043-2048 10.1099/00221287-136-10-2043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato N, Murata N. Lipid biosynthesis in the blue-green alga (cyanobacterium), Anabaena variabilis III. UDPglucose:diacylglycerol glucosyltransferase activity in vitro. Plant Cell Physiol 1982; 23:1115-1120 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato N, Murata N. Temperature shift-induced responses in lipids in the blue-green alga, Anabaena variabilis: the central role of diacylmonogalactosylglycerol in thermo-adaptation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1980; 619:353-366 10.1016/0005-2760(80)90083-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naoki S, Murata N, Miura Y, Ueta N. Effect of growth temperature on lipid and fatty acid compositions in the blue-green algae, Anabaena variabilis and Anacystis nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta 1979; 572:19-28 10.1016/0005-2760(79)90196-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allen MB, Arnon DI. Studies on nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. I. Growth and nitrogen fixation by Anabaena cylindrica Lemm. Plant Physiol 1955; 30:366-372 10.1104/pp.30.4.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phred, Phrap, Consed. http://www.phrap.com

- 59.Protocols in Production Sequencing http://www.jgi.doe.gov/sequencing/protocols/prots_production.html

- 60.Cliff SH, Chain P. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In: Arabnia HR, Homayoun V, editors. Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology.: CSREA Press; 2006. p 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007; 23:673-679 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Badger JH, Olsen GJ. CRITICA: coding region identification tool invoking comparative analysis. Mol Biol Evol 1999; 16:512-524 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline. http://genome.ornl.gov/microbial/supplemental/annotation_ref.html

- 64.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dyrløv Bendtsen J, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thiel T. Isolation and characterization of the vnfEN genes of the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol 1996; 178:4493-4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]