Abstract

Burkholderia mimosarum strain LMG 23256T is an aerobic, motile, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod that can exist as a soil saprophyte or as a legume microsymbiont of Mimosa pigra (giant sensitive plant). LMG 23256T was isolated from a nodule recovered from the roots of the M. pigra growing in Anso, Taiwan. LMG 23256T is highly effective at fixing nitrogen with M. pigra. Here we describe the features of B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T, together with genome sequence information and its annotation. The 8,410,967 bp high-quality-draft genome is arranged into 268 scaffolds of 270 contigs containing 7,800 protein-coding genes and 85 RNA-only encoding genes, and is one of 100 rhizobial genomes sequenced as part of the DOE Joint Genome Institute 2010 Genomic Encyclopedia for Bacteria and Archaea-Root Nodule Bacteria (GEBA-RNB) project.

Keywords: root-nodule bacteria, nitrogen fixation, rhizobia, Betaproteobacteria

Introduction

Members of the versatile genus Burkholderia occupy a wide range of ecological niches and are found in soil, hospital environments, associated with plants either as epiphytes, endophytes or as pathogens and some are endosymbionts in phytopathogenic fungi or plant-associated insects [1]. As several Burkholderia strains are known to exert plant-beneficial and biocontrol effects, and also contribute to adaptation to environmental stresses, there is increased interest in the use of Burkholderia in agriculture [1,2].

In addition to the different groups of rhizobia from the Alphaproteobacteria, a number of Betaproteobacteria belonging to Burkholderia and Cupriavidus are now also known to be present in legume nodules; they are sometimes referred to as betarhizobia [3-5]. Several Burkholderia species have been described from root nodules of different Mimosa species: B. caribensis from M. pudica and M. diplotricha [4,6], B. mimosarum from M. pigra and M. scabrella [7], B. nodosa from M. bimucronata and M. scabrella [8], B. phymatum from M. invisa and Machaerium lunatum [6,9] and B. sabiae from M. caesalpiniifolia [10]. Moreover, several Burkholderia strains have been shown to enter into effective symbiosis with their host [11].

B. mimosarum was described for a collection of isolates obtained from M. pigra in Taiwan, Venezuela and Brazil and one strain from M. scabrella in Brazil [7]. Since its first description, B. mimosarum has also been isolated from M. pigra nodules in China and Australia [12,13], from M. diplotricha in Papua New Guinea [14] and M. pudica in French Guiana [15]. M. pigra, as well as M. pudica and M. diplotricha, are notoriously invasive species [16]. M. pudica (sensitive plant) is a small South American shrub that has become a pan-tropical weed, while M. pigra (giant sensitive plant, black mimosa, prickly wood weed, catclaw mimosa) is a shrub that thrives in floodplains, swamps and river banks, where it creates dense spiny thickets [17]. M. diplotricha (creeping sensitive plant, nila grass, giant sensitive plant) is a climbing shrub that scrambles up other plants, quickly producing dense growth [18]. The success of these invasive weeds may in part be due to their highly effective symbiotic associations.

B. mimosarum LMG 23256T (=BCRC 17516, CCUG 54296, NBRC 106338, PAS44) originates from nodules of M. pigra in Taiwan. This legume weed is predominantly nodulated by B. mimosarum in Taiwan. Other Taiwanese Mimosa species are nodulated mainly by Cupriavidus taiwanensis and it has therefore been suggested that the Burkholderia strains were introduced to Taiwan, along with the invasive M. pigra from its native South America, where Burkholderia strains have been isolated more frequently from Mimosa sp. than C. taiwanesis [7,19].

Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T (Table 1), together with the description of the complete genome sequence and its annotation.

Table 1. Classification and general features of Burkholderia mimosarum strain LMG 23256T according to the MIGS recommendations [20].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [21] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [22] | ||

| Class Betaproteobacteria | TAS [23,24] | ||

| Order Burkholderiales | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Family Burkholderiaceae | TAS [24,26] | ||

| Genus Burkholderia | TAS [27-29] | ||

| Species Burkholderia mimosarum | TAS [7] | ||

| Strain LMG 23256T | |||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | NAS | |

| Optimum temperature | 28°C | NAS | |

| Salinity | Non-halophile | NAS | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | TAS [19] |

| Carbon source | Varied | NAS | |

| Energy source | Chemoorganotroph | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil, root nodule, on host | TAS [19] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living, symbiotic | TAS [19] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogenic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [30]* | |

| Isolation | Root nodule of Mimosa pigra | TAS [19] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Anso, Taiwan | TAS [19] |

| MIGS-5 | Soil collection date | Not recorded | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | 120.87222 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.2 | Latitude | 22.28889 | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not recorded | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not recorded | IDA |

*Strain catalogue BCCM/LMG http://bccm.belspo.be/db/lmg_search_form.php

Evidence codes – IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [31].

Classification and features

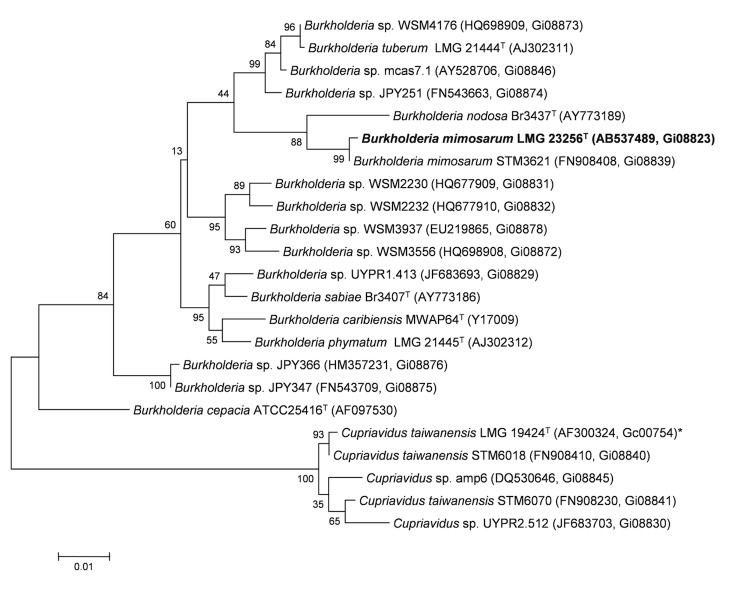

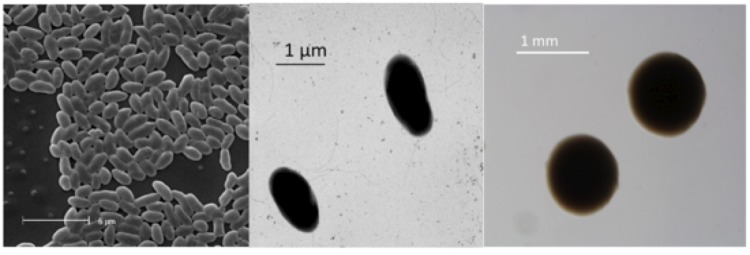

B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T is a non-sporulating, non-encapsulated, Gram-negative rod within the order Burkholderiales of the class Betaproteobacteria. The rod-shaped form varies in size; it is approximately 1.0 μm in width and 2.0 μm in length (Figure 1, Left and Figure 1, Center). It is fast-growing, forming colonies within 3-4 days when grown on half strength Lupin Agar (½LA) [32], tryptone-yeast extract agar (TY) [33] or a modified yeast-mannitol agar (YMA) [34] at 28°C. Colonies on ½LA are white-opaque, slightly domed and moderately mucoid with smooth margins (Figure 1, Right). Minimum Information about the Genome Sequence (MIGS) is provided in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T in a 16S rRNA sequence based tree. This strain shares 99% (1,121/1,124 bp) and 98% (1,101/1,125 bp) sequence identity to the 16S rRNA of the fully sequenced strain B. mimosarum STM3621 (Gi08839) and to B. nodosa Br3461T, respectively.

Figure 1.

Images of Burkholderia mimosarum strain LMG 23256T using scanning (Left) and transmission (Center) electron microscopy and the appearance of colony morphology on a solid medium (Right).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of Burkholderia mimosarum strain LMG 23256T (shown in bold print) to other members of the order Burkholderiales based on aligned sequences of the 16S rRNA gene (1,242 bp internal region). All sites were informative and there were no gap-containing sites. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA, version 5 [35]. The tree was built using the Maximum-Likelihood method with the General Time Reversible model [36]. Bootstrap analysis [37] with 500 replicates was performed to assess the support of the clusters. Type strains are indicated with a superscript T. Brackets after the strain name contain a DNA database accession number and/or a GOLD ID (beginning with the prefix G) for a sequencing project registered in GOLD [38]. Published genomes are indicated with an asterisk.

Symbiotaxonomy

B. mimosarum LMG 23256T was isolated from M. pigra growing in Anso, Taiwan and was able to nodulate its original host with high efficiency [19], as well as M. pucida and M. diplotricha [14]. LMG 23256T was shown to outcompete other rhizobia to the point of exclusion for the nodulation of the invasive M. pigra, M. pudica and M. diplotricha under flooded conditions. This predominance was negatively affected by increased nitrate levels in the soil, which thus seems to be a factor affecting rhizobial competition [14].

With regard to other plant growth promoting properties, LMG 23256T displayed no antifungal activity against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli, did not solubilize calcium-, iron- or aluminum phosphates nor reduce acetylene (ARA) on the N-free media containing fructose, lactate or mannitol as sole carbon source [39].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its environmental and agricultural relevance to issues in global carbon cycling, alternative energy production, and biogeochemical importance, and is part of the Community Sequencing Program at the U.S. Department of Energy, Joint Genome Institute (JGI) for projects of relevance to agency missions. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [38] and an improved-high-quality-draft genome sequence in IMG. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the JGI. A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information for Burkholderia mimosarum LMG 23256T.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Improved high-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One Illumina fragment library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | Illumina: 240× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Velvet version 1.1.04; Allpaths-LG version r39750 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling methods | Prodigal 1.4 |

| GOLD ID | Gi08823 | |

| NCBI project ID | 163559 | |

| Database: IMG | 2513237083 | |

| Project relevance | Symbiotic N2 fixation, agriculture |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T was cultured to mid logarithmic phase in 60 ml of TY rich medium on a gyratory shaker at 28°C [40]. DNA was isolated from the cells using a CTAB (Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide) bacterial genomic DNA isolation method (http://my.jgi.doe.gov/general/index.html).

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T was sequenced at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using Illumina technology [41]. An Illumina standard shotgun library was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, which generated 14,635,038 reads totaling 2,014 Mbp.

All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at http://my.jgi.doe.gov/general/index.html. All raw Illumina sequence data was passed through DUK, a filtering program developed at JGI, which removes known Illumina sequencing and library preparation artifacts (Mingkun, L., Copeland, A. and Han, J., unpublished). The following steps were then performed for assembly: (1) filtered Illumina reads were assembled using Velvet [42] (version 1.1.04), (2) 1–3 Kbp simulated paired end reads were created from Velvet contigs using wgsim [43], (3) Illumina reads were assembled with simulated read pairs using Allpaths–LG [44] (version r39750). Parameters for assembly steps were:

Velvet (--v --s 51 --e 71 --i 2 --t 1 --f "-shortPaired -fastq $FASTQ" --o "-ins_length 250 -min_contig_lgth 500") 10)

wgsim (-e 0 -1 76 -2 76 -r 0 -R 0 -X 0)

Allpaths–LG (PrepareAllpathsInputs:PHRED64=1 PLOIDY=1 FRAGCOVERAGE=125 JUMPCOVERAGE=25 LONGJUMPCOV=50, RunAllpath-sLG: THREADS=8 RUN=stdshredpairs TARGETS=standard VAPIWARNONLY=True OVERWRITE=True).

The final draft assembly contained 270 contigs in 268 scaffolds. The total size of the genome is 8.4 Mbp and the final assembly is based on 2,014 Mbp of Illumina data, which provides an average 240× coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [45] as part of the DOE-JGI annotation pipeline [46]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. The tRNAScanSE tool [47] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNA genes were found by searches against models of the ribosomal RNA genes built from SILVA [48]. Other non–coding RNAs such as the RNA components of the protein secretion complex and the RNase P were identified by searching the genome for the corresponding Rfam profiles using INFERNAL [49]. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG-ER) platform [50].

Genome properties

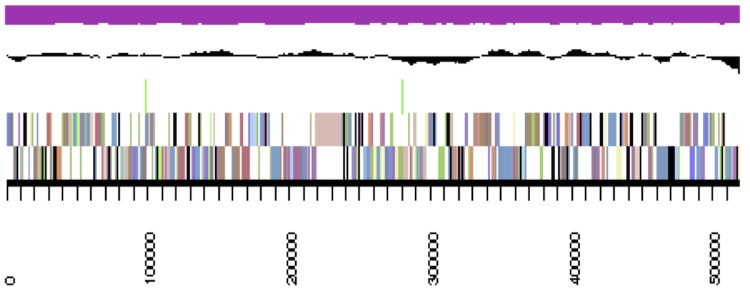

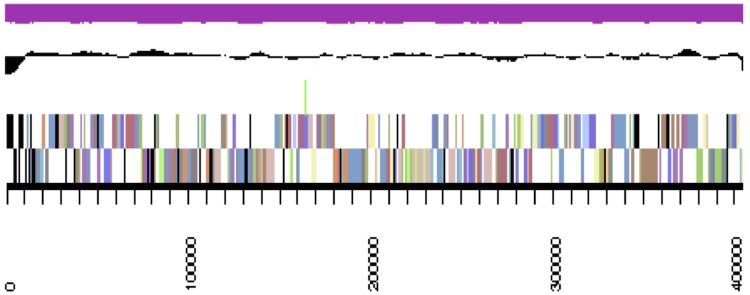

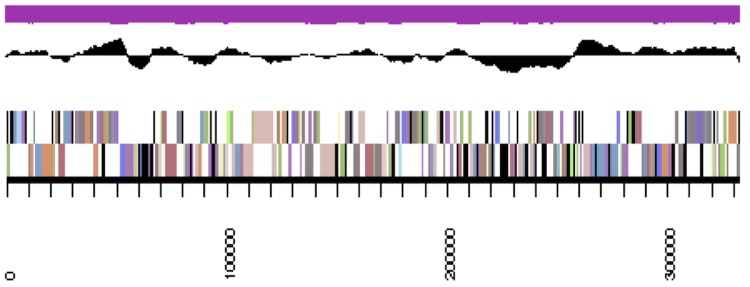

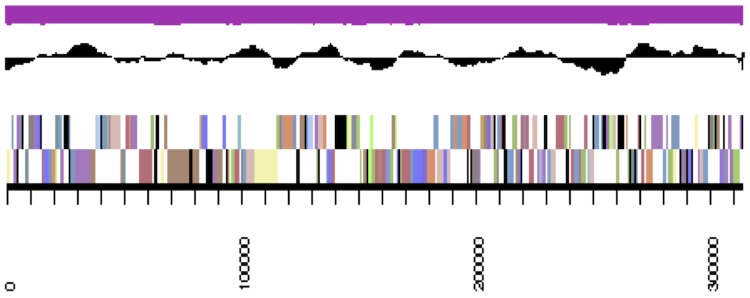

The genome is 8,410,967 nucleotides 63.89% GC content (Table 3) and comprised of 268 scaffolds (the four largest scaffolds are shown in Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and Figure 3d) of 270 contigs. From a total of 7,885 genes, 7,800 were protein encoding and 85 RNA only encoding genes. The majority of genes (75.13%) were assigned a putative function whilst the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics for B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 8,410,967 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 7,084,175 | 84.23 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 5,373,761 | 63.89 |

| Number of scaffolds | 268 | |

| Number of contigs | 270 | |

| Total gene | 7,885 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 85 | 1.08 |

| rRNA operons* | 1 | 0.01 |

| Protein-coding genes | 7,800 | 98.92 |

| Genes with function prediction | 5,924 | 75.13 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 5,870 | 74.45 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 6,242 | 79.16 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 673 | 8.54 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,680 | 21.31 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

*5 copies of 5S, 1 copy of 16S and 2 copies of 23S rRNA.

Figure 3a.

Graphical map of LMG 23256_A19UDRAFT_scaffold_0.1 of the B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T genome. From bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Figure 3b.

Graphical map of LMG 23256_A19UDRAFT_scaffold_1.2 of the B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T genome. From bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Figure 3c.

Graphical map of LMG 23256_A19UDRAFT_scaffold_2.3 of the B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T genome. From bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Figure 3d.

Graphical map of LMG 23256_A19UDRAFT_scaffold_3.4 of the B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T genome. From bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of protein coding genes of B. mimosarum strain LMG 23256T associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 191 | 2.89 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 6 | 0.09 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 588 | 8.89 | Transcription |

| L | 415 | 6.28 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 50 | 0.76 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 71 | 1.07 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 376 | 5.69 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 414 | 6.26 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 146 | 2.21 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 161 | 2.43 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 208 | 3.15 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 489 | 7.39 | Energy production conversion |

| G | 435 | 6.58 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 623 | 9.42 | Amino acid transport metabolism |

| F | 98 | 1.48 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 226 | 3.42 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 316 | 4.78 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 293 | 4.43 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 231 | 3.49 | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 745 | 11.27 | General function prediction only |

| S | 529 | 8.00 | Function unknown |

| - | 2,015 | 25.55 | Not in COGS |

| 6,612 | - | Total |

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received from the Murdoch University Strategic Research Fund through the Crop and Plant Research Institute (CaPRI) and the Centre for Rhizobium Studies (CRS) at Murdoch University.

References

- 1.Compant S, Nowak J, Coenye T, Clement C, Ait Barka E. Diversity and occurrence of Burkholderia spp. in the natural environment. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008; 32:607-626 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salles JF, van Elsas JD, van Veen JA. Effect of agricultural management regime on Burkholderia community structure in soil. Microb Ecol 2006; 52:267-279 10.1007/s00248-006-9048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moulin L, Munive A, Dreyfus B, Boivin-Masson C. Nodulation of legumes by members of the beta-subclass of Proteobacteria. Nature 2001; 411:948-950 10.1038/35082070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen WM, Moulin L, Bontemps C, Vandamme P, Bena G, Boivin-Masson C. Legume symbiotic nitrogen fixation by beta-proteobacteria is widespread in nature. J Bacteriol 2003; 185:7266-7272 10.1128/JB.185.24.7266-7272.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen WM, Laevens S, Lee TM, Coenye T, De Vos P, Mergeay M, Vandamme P. Ralstonia taiwanensis sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Mimosa species and sputum of a cystic fibrosis patient. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:1729-1735 10.1099/00207713-51-5-1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandamme P, Goris J, Chen WM, de Vos P, Willems A. Burkholderia tuberum sp. nov. and Burkholderia phymatum sp. nov., nodulate the roots of tropical legumes. Syst Appl Microbiol 2002; 25:507-512 10.1078/07232020260517634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen WM, James EK, Coenye T, Chou JH, Barrios E, de Faria SM, Elliott GN, Sheu SY, Sprent JI, Vandamme P. Burkholderia mimosarum sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Mimosa spp. from Taiwan and South America. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1847-1851 10.1099/ijs.0.64325-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen WM, de Faria SM, James EK, Elliott GN, Lin KY, Chou JH, Sheu SY, Cnockaert M, Sprent JI, Vandamme P. Burkholderia nodosa sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of the woody Brazilian legumes Mimosa bimucronata and Mimosa scabrella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:1055-1059 10.1099/ijs.0.64873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott GN, Chen WM, Chou JH, Wang HC, Sheu SY, Perin L, Reis VM, Moulin L, Simon MF, Bontemps C, et al. Burkholderia phymatum is a highly effective nitrogen-fixing symbiont of Mimosa spp. and fixes nitrogen ex planta. New Phytol 2007; 173:168-180 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01894.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen WM, de Faria SM, Chou JH, James EK, Elliott GN, Sprent JI, Bontemps C, Young JP, Vandamme P. Burkholderia sabiae sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Mimosa caesalpiniifolia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2174-2179 10.1099/ijs.0.65816-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen WM, de Faria SM, Straliotto R, Pitard RM, Simões-Araùjo JL, Chou J, Chou Y, Barrios E, Prescott AR, Elliott GN, et al. Proof that Burkholderia strains form effective symbioses with legumes: a study of novel Mimosa-nodulating strains from South America. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005; 71:7461-7471 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7461-7471.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker MA, Wurtz AK, Paynter Q. Nodule symbiosis of invasive Mimosa pigra in Australia and in Ancestral habitats: A comparative analysis. Biol Invasions 2007; 9:127-138 10.1007/s10530-006-0009-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XY, Wu W, Wang ET, Zhang B, Macdermott J, Chen WX. Phylogenetic relationships and diversity of beta-rhizobia associated with Mimosa species grown in Sishuangbanna, China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:334-342 10.1099/ijs.0.020560-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott GN, Chou JH, Chen WM, Bloemberg GV, Bontemps C, Martínez-Romero E, Velázquez E, Young JPW, Sprent JI, James EK. Burkholderia spp. are the most competitive symbionts of Mimosa, particularly under N-limited conditions. Environ Microbiol 2009; 11:762-778 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra RP, Tisseyre P, Melkonian R, Chaintreuil C, Miche L, Klonowska A, Gonzalez S, Bena G, Laguerre G, Moulin L. Genetic diversity of Mimosa pudica rhizobial symbionts in soils of French Guiana: investigating the origin and diversity of Burkholderia phymatum and other beta-rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2012; 79:487-503 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan D, Thu P, Dell B. Invasive plant species in the national parks of Vietnam. Forests 2012; 3:997-1016 10.3390/f3040997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostermeyer N, Grace BS. Establishment, distribution and abundance of Mimosa pigra biological control agents in northern Australia: implications for biological control. BioControl 2007; 52:703-720 10.1007/s10526-006-9054-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacific Forest Invasive Species Network www.fao.org/forestry/13377-0977cb34791475aa6a7a360640f09778.pdf

- 19.Chen WM, James EK, Chou JH, Sheu SY, Yang SZ, Sprent JI. Beta-rhizobia from Mimosa pigra, a newly discovered invasive plant in Taiwan. New Phytol 2005; 168:661-675 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen M, Angiuoli SV, et al. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes "Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence " (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TE. Class II. Betaproteobacteria In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second ed. Volume 2. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005, p. 575. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TE. Order 1. Burkholderiales In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second ed. Volume 2. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005, p. 575. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TE. Family I. Burkholderiaceae In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second ed. Volume 2. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005, p. 575. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. List No. 45. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1993; 43:398-399 10.1099/00207713-43-2-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Oyaizu H, Yano I, Hotta H, Hashimoto Y, Ezaki T, Arakawa M. Proposal of Burkholderia gen. nov. and transfer of seven species of the genus Pseudomonas homology group II to the new genus, with the type species Burkholderia cepacia (Palleroni and Holmes 1981) comb. nov. Microbiol Immunol 1992; 36:1251-1275 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillis M, Van TV, Bardin R, Goor M, Hebbar P, Willems A, Segers P, Kersters K, Heulin T, Fernandez MP. Polyphasic taxonomy in the genus Burkholderia leading to an emended description of the genus and proposition of Burkholderia vietnamiensis sp. nov. for N2-fixing isolates from rice in Vietnam. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45:274-289 10.1099/00207713-45-2-274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agents B. Technical rules for biological agents. TRBA (http://www.baua.de):466.

- 31.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howieson JG, Ewing MA, D'antuono MF. Selection for acid tolerance in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Soil 1988; 105:179-188 10.1007/BF02376781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beringer JE. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol 1974; 84:188-198 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terpolilli JJ. Why are the symbioses between some genotypes of Sinorhizobium and Medicago suboptimal for N2 fixation? Perth: Murdoch University; 2009. 223 p. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783-791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Silva K, Cassetari Ade S, Lima AS, De Brandt E, Pinnock E, Vandamme P, Moreira FM. Diazotrophic Burkholderia species isolated from the Amazon region exhibit phenotypical, functional and genetic diversity. Syst Appl Microbiol 2012; 35:253-262 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeve WG, Tiwari RP, Worsley PS, Dilworth MJ, Glenn AR, Howieson JG. Constructs for insertional mutagenesis, transcriptional signal localization and gene regulation studies in root nodule and other bacteria. Microbiology 1999; 145:1307-1316 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett S. Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics 2004; 5:433-438 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zerbino DR. Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 2010;Chapter 11:Unit 11 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.wgsim. https://github.com/lh3/wgsim

- 44.Gnerre S, MacCallum I, Przybylski D, Ribeiro FJ, Burton JN, Walker BJ, Sharpe T, Hall G, Shea TP, Sykes S, et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:1513-1518 10.1073/pnas.1017351108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Szeto E, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The DOE-JGI Standard operating procedure for the annotations of microbial genomes. Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:63-67 10.4056/sigs.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K. Fuchs BdM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:7188-7196 10.1093/nar/gkm864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.INFERNAL http://infernal.janelia.org

- 50.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]