Abstract

Strain HIMB11 is a planktonic marine bacterium isolated from coastal seawater in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii belonging to the ubiquitous and versatile Roseobacter clade of the alphaproteobacterial family Rhodobacteraceae. Here we describe the preliminary characteristics of strain HIMB11, including annotation of the draft genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis with other members of the Roseobacter lineage. The 3,098,747 bp draft genome is arranged in 34 contigs and contains 3,183 protein-coding genes and 54 RNA genes. Phylogenomic and 16S rRNA gene analyses indicate that HIMB11 represents a unique sublineage within the Roseobacter clade. Comparison with other publicly available genome sequences from members of the Roseobacter lineage reveals that strain HIMB11 has the genomic potential to utilize a wide variety of energy sources (e.g. organic matter, reduced inorganic sulfur, light, carbon monoxide), while possessing a reduced number of substrate transporters.

Keywords: marine bacterioplankton, Roseobacter, aerobic anoxygenic phototroph, dimethylsulfoniopropionate

Introduction

Bacteria belonging to the Roseobacter lineage of marine Alphaproteobacteria account for a substantial fraction (ranging ~10 – 25%) of bacterioplankton cells in surface ocean seawater [1-4], making them one of a relatively small number of suitable targets for scientists investigating the ecology of abundant marine bacterial groups. Focused genome sequencing efforts have provided significant insights into the functional and ecological roles for this group [5-7]. In 2004, the first member of this group to have its genome sequenced, Ruegeria pomeroyi (basonym Silicibacter pomeroyi) strain DSS-3 [8], revealed strategies used by the Roseobacter group for nutrient acquisition in the marine environment. To date, over 40 genomes have been sequenced from members of the Roseobacter lineage. Comparative analysis among 32 of these genomes indicates that members of this group are ecological generalists, having relatively plastic requirements for carbon and energy metabolism, which may allow them to respond to a diverse range of environmental conditions [9]. For example, members of the Roseobacter lineage have the genomic potential to obtain energy via oxidation of organic substrates, oxidation of inorganic compounds, and/or sunlight-driven electron transfer via bacteriochlorophyll a, proteorhodopsin, or xanthorhodopsin phototrophic systems. Genome analyses as well as culture experiments have also revealed a variety of mechanisms by which roseobacters may associate and interact with phytoplankton and other eukaryotes. These include genes involved in uptake of compounds produced by algae such as peptides, amino acids, putrescine, spermidine, and DMSP [10,11], as well as genes for chemotaxis, attachment, and secretion [12].

Strain HIMB11 was isolated from surface seawater collected from Kaneohe Bay off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, USA in May, 2005. Subsequent 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons revealed it to be a member of the Roseobacter clade of marine bacterioplankton [13] that was highly abundant after a storm-induced phytoplankton bloom in the bay [14]. Here, we present a preliminary set of features for strain HIMB11, a description of the draft genome sequence and annotation, and a comparative analysis with 35 other genome sequences from members of the Roseobacter lineage. Genome annotation revealed strain HIMB11 to have the genetic potential for bacteriochlorophyll-based aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic (AAnP) metabolism and degradation of the algal-derived compound DMSP along with production of the climate-relevant gas dimethylsulfide (DMS), and oxidation of the greenhouse gas carbon monoxide (CO). Collectively, these features indicate the potential for strain HIMB11 to participate in the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur and carbon, and concomitantly affect global climate processes.

Classification and features

Strain HIMB11 was isolated by a high-throughput, dilution-to-extinction approach [15] from surface seawater collected near the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, USA, in the tropical North Pacific Ocean. The strain was isolated in seawater sterilized by tangential flow filtration and amended with low concentrations of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus (1.0 µM NH4Cl, 1.0 µM NaNO3, and 0.1 µM KH2PO4).

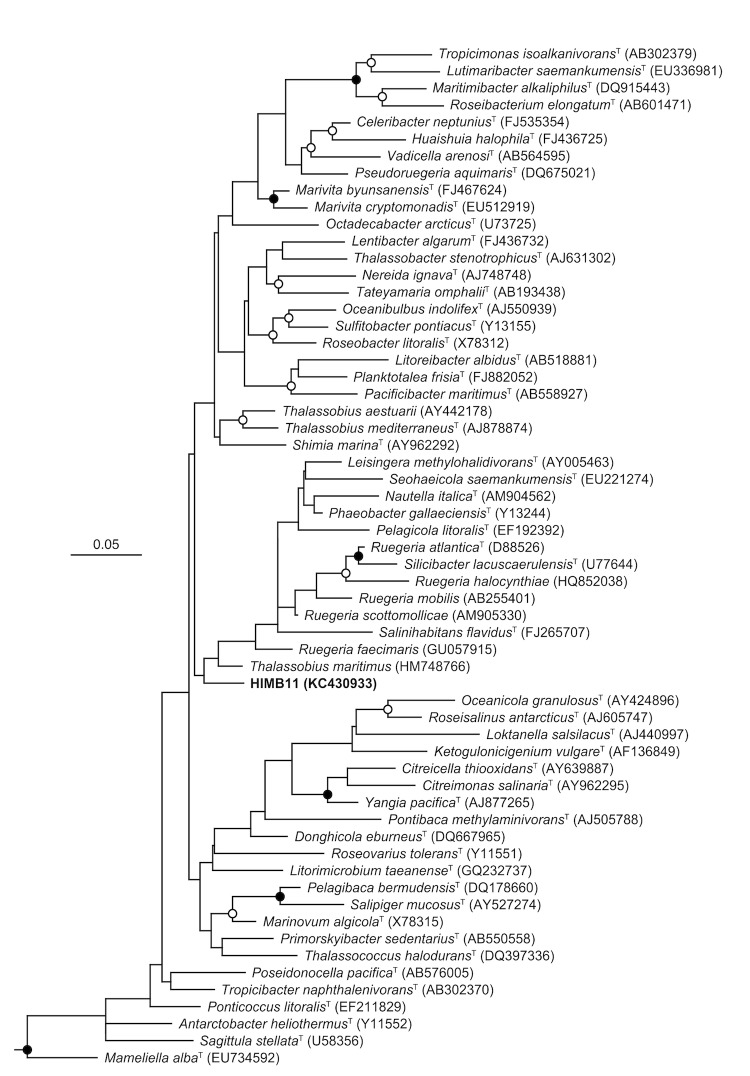

Comparative analysis of the HIMB11 16S rRNA gene sequence to those from cultured, sequenced roseobacters indicates that HIMB11 occupies a unique lineage that is divergent from the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Roseobacter strains already in culture (Figure 1). Based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant database, the HIMB11 16S rRNA gene sequence is most similar (~99% nucleotide identity) to a large number of environmental gene clones obtained from various marine environments that exclusively fall in the Roseobacter lineage of Alphaproteobacteria.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships between HIMB11 and bacterial strains belonging to the Roseobacter clade. SSU rRNA gene sequences were aligned with version 111 of the ‘All-Species Living Tree’ project SSU rRNA gene database [16] using the ARB software package [17]. The phylogeny was constructed from nearly full-length gene sequences using the RAxML maximum likelihood method [18] within ARB, filtered to exclude alignment positions that contained gaps or ambiguous nucleotides in any of the sequences included in the tree. Bootstrap analyses were determined by RAxML [19] via the raxmlGUI graphical front end [20]. The scale bar corresponds to 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position. Open circles indicate nodes with bootstrap support between 50-80%, while closed circles indicate bootstrap support >80%, from 500 replicates. A variety of Archaea were used as outgroups.

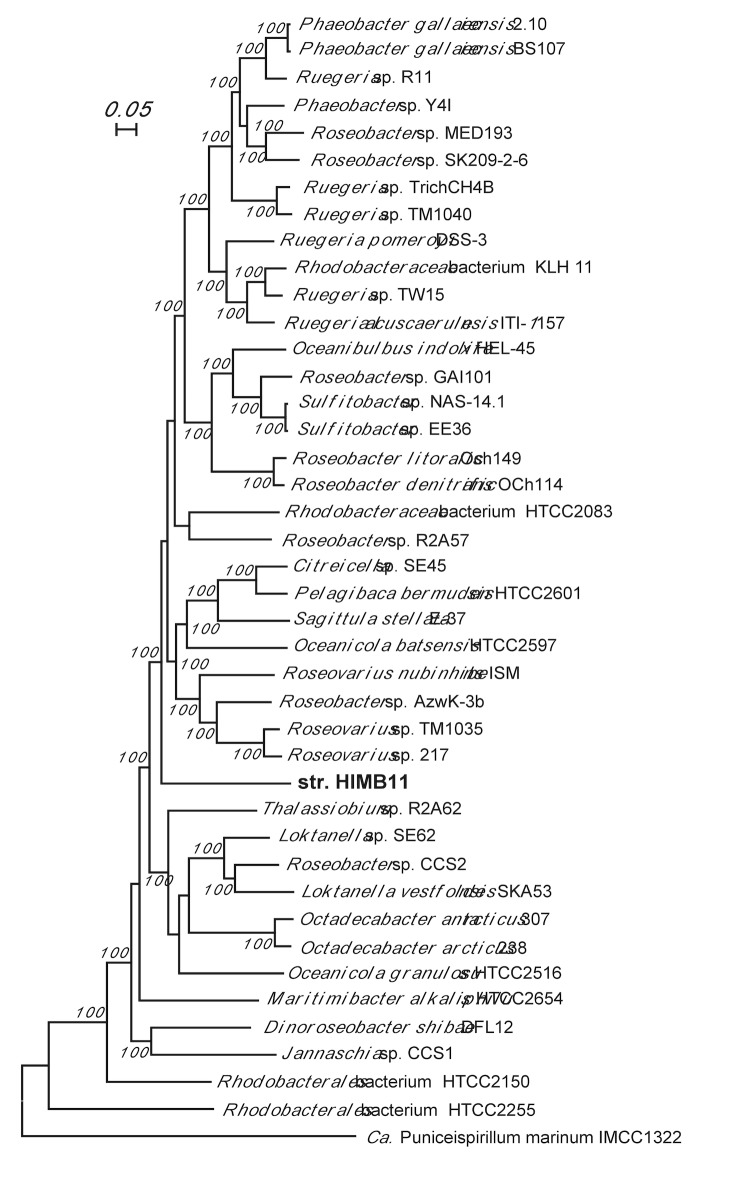

Because of the significant sequence variation in 16S rRNA genes (up to 11%) and the prevalence of horizontal gene transfer within the clade, establishing a taxonomic framework for roseobacters remains a challenge [9]. When genome sequence data is available, it is often more informative to perform a phylogenomic analysis based on shared orthologs versus 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis alone [9,21]. A maximum likelihood tree constructed using 719 shared orthologous protein sequences supported the 16S rRNA gene-based analysis by revealing that HIMB11 formed a unique sublineage of the Roseobacter clade (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree derived from a concatenation of 719 shared single-copy orthologous protein sequences from strain HIMB11, 40 other Roseobacter members, and the SAR116 clade member Ca. Puniceispirillum marinum IMCC1322 (outgroup) using the RAxML maximum likelihood method [18]. After a reciprocal BLAST search [22] was performed for all possible genome pairs at the amino acid level using an E value of 10-6, orthologous genes in each of the genome pairs were identified using the MSOAR software [23], which assigns orthologs by considering both sequence similarity and gene context information. One genome was picked at random as the reference genome, and pairwise orthologs were linked to the reference. Values at the nodes show the number of times the clade defined by that node appeared in the 100 bootstrapped data sets. The scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site. Bootstrap values lower than 50% were not displayed.

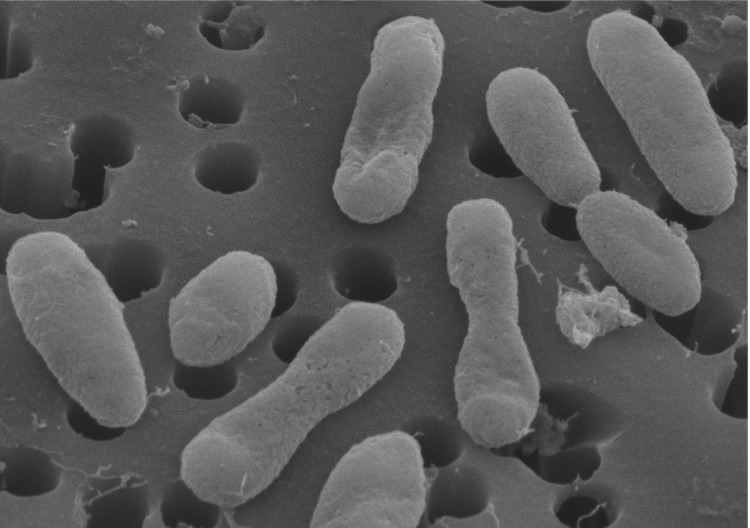

HIMB11 cells are short, irregular rods (0.3-0.5 x 0.8 µm) that are generally smaller in size than previously reported for other cultured Roseobacter strains (e.g. described taxa in Bergey’s Manual range from 0.5-1.6 – 1.0-4.0 µm) [24] (Figure 3). HIMB11 is likely motile, as the genes necessary to build flagella are present (e.g. fli, flg). Based on the ability of HIMB11 to grow in dark or light on a medium consisting solely of sterile seawater amended with inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, and the absence any of the known pathways for inorganic carbon fixation, the strain is presumed to acquire carbon and energy via the oxidation of components of the dissolved organic carbon pool in natural seawater. Based on the presence of carbon-monoxide-oxidizing genes (i.e. coxL, forms I and II) [25,26] as well as bacteriochlorophyll-based phototrophy genes (e.g. puf, puh, bch) [27,28], HIMB11 is hypothesized to oxidize both organic and inorganic compounds as well as obtain energy from light [5]. A summary of these and other features is shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrograph of strain HIMB11. For scale, the membrane pore size is 0.2 μm in diameter.

Table 1. Classification and general features of strain HIMB11 according to the MIGS recommendations [29].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [30] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [31] | ||

| Class Alphaproteobacteria | TAS [32,33] | ||

| Order Rhodobacterales | TAS [32,34] | ||

| Family Rhodobacteraceae | TAS [32,35] | ||

| Genus not assigned | |||

| Species not assigned | |||

| Strain HIMB11 | |||

| Gram stain | Negative | NAS | |

| Cell shape | Short irregular rods | IDA | |

| Motility | Flagella | NAS | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | Unknown | ||

| Carbon source | Ambient seawater DOC | TAS [36] | |

| Energy source | Mixotrophic | NAS | |

| Terminal electron receptor | |||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Seawater | IDA |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | ~35.0 ‰ | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | Aerobic | NAS |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | TAS [36] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | None | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii | TAS [14] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 18 May, 2005 | TAS [14] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude - Longitude | 21.44, -157.78 | TAS [14] |

| MIGS-4.2 | |||

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | ~1 m | TAS [14] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude |

a) Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [37].

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The genome of strain HIMB11 was selected for sequencing based on its phylogenetic affiliation with the widespread and ecologically important Roseobacter clade of marine bacterioplankton and its periodically high abundance in coastal Hawaii seawater [14]. The genome sequence was completed on May 25, 2011, and presented for public access on September 15, 2013. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) as project Gi09592. The Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number AVDB00000000. The version described in this paper is version AVBD01000000. Table 2 presents the main project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [29].

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One standard 454 pyrosequence titanium library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 121× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| Genome Database release | IMG; 2506210027 | |

| Genbank ID | AVDB00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 15, 2013 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi09592 | |

| Project relevance | Environmental |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Strain HIMB11 was grown at 27 °C in 60 L of coastal Hawaii seawater sterilized by tangential flow filtration and supplemented with 10 µM NH4Cl, 1.0 µM KH2PO4, and 1.0 µM NaNO3 (final concentrations). Cells from the liquid culture were collected on a membrane filter, and DNA was isolated using a standard phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction protocol. A total of 50 μg of DNA was obtained.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The HIMB11 genome was sequenced at the Pennsylvania State University Center for Comparative Genomics and Bioinformatics (University Park, PA, USA) using a 454 GS FLX platform and Titanium chemistry from 454 Life Sciences (Branford, CT, USA). The sequencing library was prepared in accordance with 454 instructions and was carried out on a full 454 picotiter plate. This yielded 1,550,788 reads with an average length of 359 bp, totaling 556,821,617 bp. A subset of 1,336,895 reads was ultimately assembled using the Newbler assembler version 2.5.3, yielding a final draft genome of 34 contigs representing 3,098,747 bp. This provided 121× coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal 1.4 [38] as part of the genome annotation pipeline in the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) system [39,40] developed by the Joint Genome Institute (Walnut Creek, CA, USA). Predicted coding sequences were translated and used as queries against the NCBI non-redundant database and UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. The tRNAScanSE tool [41] was used to identify tRNA genes, and ribosomal RNAs were identified using RNAmmer [42]. Other non-coding RNAs were found by searching the genome for corresponding Rfam profiles using INFERNAL [43]. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the IMG-ER platform.

Genome properties

The HIMB11 draft genome is 3,098,747 bp long and comprises 34 contigs ranging in size from 454 to 442,822 bp, with an overall GC content of 49.73% (Table 3). Of the 3,237 predicted genes, 3,183 (98.33%) were protein-coding genes, and 54 were RNAs. Most (78%) protein-coding genes were assigned putative functions, while the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,098,747 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,812,982 | 90.78 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,541,077 | 49.73 |

| Total genes | 3,237 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 54 | 1.67 |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,183 | 98.33 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | ||

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,523 | 77.94 |

| 1 or more conserved domains | ||

| 2 or more conserved domains | ||

| 3 or more conserved domains | ||

| 4 or more conserved domains | ||

| Genes with signal peptides | 919 | 28.39 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 654 | 20.20 |

| Paralogous groups |

a) The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 158 | 5.6 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 159 | 5.7 | Transcription |

| L | 104 | 3.7 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 3 | 0.1 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 24 | 0.9 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 22 | 0.8 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 74 | 2.6 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 133 | 4.7 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 40 | 1.4 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 38 | 1.4 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 118 | 4.2 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 196 | 7.0 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 165 | 5.9 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 334 | 11.9 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 73 | 2.6 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 157 | 5.6 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 154 | 5.5 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 112 | 4.0 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 123 | 4.4 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 379 | 13.5 | General function prediction only |

| S | 238 | 8.5 | Function unknown |

| - | 714 | 22.06 | Not in COGs |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Insights from the Genome Sequence

Metabolism of HIMB11

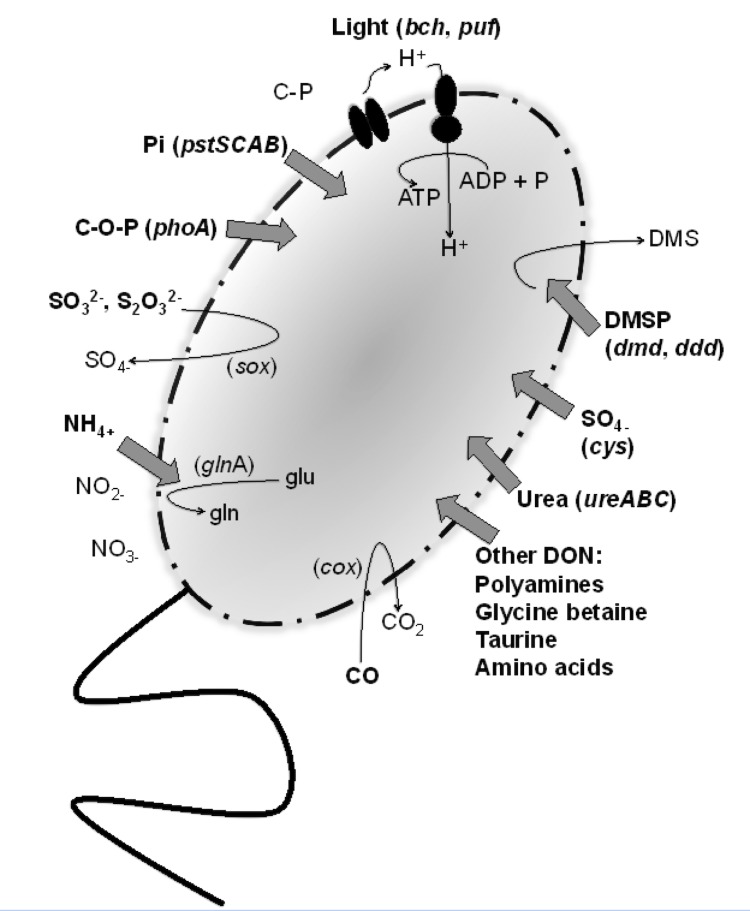

Major pathways of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur acquisition, as well as alternative metabolisms and means of energy acquisition (e.g. light, CO), were annotated based on the presence and absence of key genes involved in these processes. A summary is provided in Figure 4. HIMB11 appears to possess an incomplete glycolysis pathway (pfkC and pgm are absent), yet it possesses the genes necessary for gluconeogenesis. HIMB11 harbors genes for the Entner-Doudoroff and pentose phosphate pathways, as well as pyruvate carboxylase to perform anaplerotic CO2 fixation. HIMB11 does not appear to use inorganic forms of nitrogen other than ammonium, as there are no genes present that are involved in nitrogen fixation, nitrate or nitrite reduction, nitric oxide reduction, nitrous oxide reduction, hydroxylamine oxidation, or nitroalkane denitrification. Instead, HIMB11 is hypothesized to rely solely on reduced and organic nitrogen sources; there are transporters for ammonium (amtB) and a variety of other nitrogen-containing substrates (e.g. amino acids, polyamines, glycine betaine, taurine), as well as genes for urease (ureABC). Strain HIMB11 possesses a high-affinity phosphate transporter accompanied by regulatory genes (pstSCAB, phoUBR) and alkaline phosphatase (phoA), suggesting that it can utilize both inorganic and organic forms of phosphorus; it does not harbor low-affinity phosphate transport (pitA) or the genes for phosphonate utilization (phnGHIJKLM).

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanisms for the acquisition of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, and energy in HIMB11. Substrates that are hypothesized to be transported and used by HIMB11 are in bold. Genes that designate these mechanisms are indicated. DMSP, dimethylsulfoniopropionate; DMS, dimethylsulfide; DON, dissolved organic nitrogen; C-O-P, phosphoesters; C-P, phosphonates; Pi, phosphate.

HIMB11 possesses genes for assimilatory sulfate reduction (cys) and for the metabolism of reduced, organic sulfur compounds (e.g. amino acids, DMSP). DMSP is an osmolyte produced by certain phytoplankton, including dinoflagellates and coccolithophores [44,45], and acts as a major source of both carbon and sulfur for marine bacterioplankton in ocean surface waters [46-49]. Roseobacters are frequently abundant during DMSP-producing algal blooms [1], and members of this group have become models for the study of bacterial transformations of DMSP [50]. There are two competing pathways for DMSP degradation: the demethylation pathway that leads to assimilation of sulfur (dmdA, -B, -C, -D), and the cleavage pathway that leads to the release of DMS (dddD, -L, -P, -Q, -W, -Y) [51]. DMS is a climate-active gas that has been implicated in the formation of atmospheric-cooling aerosols and clouds. The genome of HIMB11 harbors versions of both sides of the pathway (dmdA, -B, -C, -D’ and dddP, -D).

The HIMB11 genome contains genes that encode for a diverse array of energy acquisition strategies. The presence of the sox gene cluster indicates that HIMB11 is putatively capable of oxidizing reduced inorganic sulfur compounds [8] as a mechanism for lithoheterotrophic growth. Additional modes of energy acquisition encoded by the HIMB11 genome include pathways for CO oxidation to CO2 via carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (i.e. cox operons, including coxL, forms I and II) [25,26], degradation of aromatics (i.e. gentisate, benzoate, phenylacetic acid), and bacteriochlorophyll-based anoxygenic photosynthesis. Photosynthetic genes are organized in a photosynthesis gene cluster (PGC) and include genes for the photosynthetic reaction center (puf and puh), light harvesting complexes, biosynthesis of bacteriochlorphyll a and carotenoids, and regulatory factors (bch and crt). Two conserved regions within the PGC that were identified in a recent study examining the structure and arrangement of PGCs in ten AAnP bacterial genomes of different phylogenies, bchFNBHLM-LhaA-puhABC and crtF-bchCXYZ [28], were also found to be conserved in the HIMB11 genome. The arrangement of the puf genes (pufQBALMC) as well as the puh genes (puhABC-hyp-ascF-puhE) in HIMB11 is very similar to what has been described before for other Roseobacter strains [28]. Putative genes containing the sensor domain BLUF (blue-light-utilizing flavin adenine dinucleotide) were also found in HIMB11. BLUF sensor domains have been hypothesized to be involved in a light-dependent regulation of the photosynthesis operon and may enable light sensing for phototrophy [5,52].

Genome comparisons with other members of the Roseobacter clade

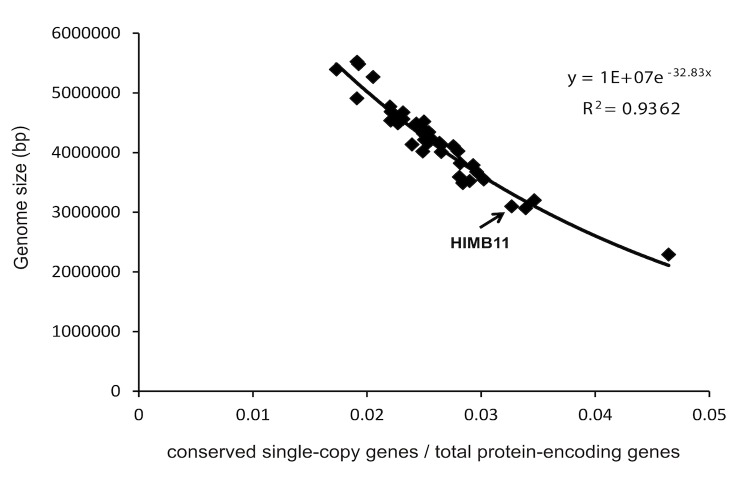

A regression model was used to estimate the genome size of HIMB11 based on the genomes of 40 Roseobacter strains (Figure 5). The model considers the number of nucleotides sequenced versus the ratio of the number of conserved single-copy genes universally present in Roseobacter genomes to the number of predicted protein-encoding genes. These data were fit to an exponential regression model (R2=0.94), which estimates the genome coverage of the draft HIMB11 genome to be 90.6% and the full genome size to be 3.42 Mb. This is relatively small compared to most cultured Roseobacter genomes (median 4.35 Mb) with only one notable exception (Roseobacter member HTCC2255, 2.21 Mb).

Figure 5.

Regression model for strain HIMB11 genome size estimation based on the genomes of 40 cultured Roseobacter strains. The x-axis shows the ratio of the number of conserved single-copy genes universally present in fully sequenced Roseobacter genomes to the number of predicted protein-encoding genes. The y-axis is the number of nucleotides sequenced. The data were fit to an exponential regression model (R2=0.94), and the model was used to estimate the genome size of HIMB11 to be 3.42 Mb.

At the time of this analysis, 35 other Roseobacter genomes were publically available in the IMG-ER database (Table 5). The effect of a reduced genome size is readily apparent with respect to the transporter content of the HIMB11 genome: it possesses a highly reduced number of genes devoted to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters. ABC transporters use energy from ATP hydrolysis to transport a wide range of substrates across the membrane (e.g. ions, amino acids, peptides, sugars). While the 35 public Roseobacter genomes contain on average 279 genes involved in ABC transport (171 to 443 per genome), HIMB11 has only 169 genes for ABC transport systems. TRAP transporters are also underrepresented in the HIMB11 genome. These are a large prokaryotic family of solute transporters that contain a substrate binding protein (DctP) and two membrane proteins (DctQ and DctM). By relying on electrochemical ion gradients rather than ATP for transport [53], they mediate the uptake of a number of different substrates (e.g. succinate, malate, fumarate, pyruvate, taurine, ectoine, DMSP). Roseobacter genomes contain on average 60 genes devoted to TRAP transporter systems (23 to 135 genes per genome), while the HIMB11 genome harbors 26 TRAP transporter genes.

Table 5. Publicly available Roseobacter clade genomes use for comparative analysis with strain HIMB11, as of IMG release 3.4.

| Organism name | Status | Size (bp) | Gene Count | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citreicella sp. SE45 | Draft | 5,523,231 | 5,499 | 67 |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL-12, DSM 16493 | Finished | 4,417,868 | 4,271 | 66 |

| Jannaschia sp. CCS1 | Finished | 4,404,049 | 4,339 | 62 |

| Loktanella sp. CCS2 | Draft | 3,497,325 | 3,703 | 55 |

| Loktanella vestfoldensis SKA53 | Draft | 3,063,691 | 3,117 | 60 |

| Maritimibacter alkaliphilus HTCC2654 | Draft | 4,529,231 | 4,763 | 64 |

| Oceanibulbus indolifex HEL-45 | Draft | 4,105,524 | 4,208 | 60 |

| Oceanicola batsensis HTCC2597 | Draft | 4,437,668 | 4,261 | 66 |

| Oceanicola granulosus HTCC2516 | Draft | 4,039,111 | 3,855 | 70 |

| Octadecabacter antarcticus 238 | Draft | 5,393,715 | 5,883 | 55 |

| Octadecabacter antarcticus 307 | Draft | 4,909,025 | 5,544 | 55 |

| Pelagibaca bermudensis HTCC2601 | Draft | 5,425,920 | 5,519 | 66 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis 2.10 | Draft | 4,157,399 | 4,017 | 60 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis BS107 | Draft | 4,232,367 | 4,136 | 60 |

| Rhodobacterales sp. HTCC2083 | Draft | 4,018,415 | 4,226 | 53 |

| Rhodobacterales sp. HTCC2150 | Draft | 3,582,902 | 3,713 | 49 |

| Rhodobacterales sp. Y4I | Draft | 4,344,244 | 4,206 | 64 |

| Rhodobacterales sp. HTCC2255 | Draft | 2,224,475 | 2,209 | 37 |

| Roseobacter denitrificans OCh 114 | Finished | 4,331,234 | 4,201 | 59 |

| Roseobacter sp. AzwK-3b | Draft | 4,178,704 | 4,197 | 62 |

| Roseobacter sp. MED193 | Draft | 4,652,716 | 4,605 | 57 |

| Roseobacter sp. SK209-2-6 | Draft | 4,555,826 | 4,610 | 57 |

| Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM | Draft | 3,668,667 | 3,605 | 64 |

| Roseovarius sp. 217 | Draft | 4,762,632 | 4,823 | 61 |

| Roseovarius sp. TM1035 | Draft | 4,209,812 | 4,158 | 61 |

| Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 | Finished | 4,601,053 | 4,355 | 64 |

| Ruegeria sp. KLH11 | Draft | 4,487,498 | 4,338 | 58 |

| Ruegeria sp. TM1040 | Finished | 4,153,699 | 3,964 | 60 |

| Sagittula stellata E-37 | Draft | 5,262,893 | 5,121 | 65 |

| Silicibacter lacuscaerulensis ITI-1157 | Draft | 3,523,710 | 3,677 | 63 |

| Silicibacter sp. TrichCH4B | Draft | 4,689,084 | 4,814 | 59 |

| Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 | Draft | 3,547,243 | 3,542 | 60 |

| Sulfitobacter sp. GAI101 | Draft | 4,527,951 | 4,258 | 59 |

| Sulfitobacter sp. NAS-14.1 | Draft | 4,002,069 | 4,026 | 60 |

| Thalassiobium sp. R2A62 | Draft | 3,487,925 | 3,744 | 55 |

In contrast, drug/metabolite transporters (DMTs), which are another abundant group of transporters found in roseobacters [5], are abundant in HIMB11. DMTs are a ubiquitous superfamily (containing 14 families, six of which are prokaryotic) of drug and metabolite transporters, of which few are functionally characterized [54]. In prokaryotes, most act as pumps for the efflux of drugs and metabolites. On average, individual Roseobacter genomes harbor 27 genes for DMTs (19 to 37 per genome). HIMB11 has 33 DMT genes, which is further elevated when normalized to its small genome size. Thus, the reductive trend for ABC and TRAP transporters is reversed in the DMT family of transporters, potentially a result of selective pressure for the efflux of toxins/metabolites.

Conclusion

HIMB11 represents a member of the Roseobacter lineage that is phylogenomically distinct from other cultured, sequenced members of the Roseobacter clade. This uniqueness is further supported by its small genome and cell size relative to other members of this group that have been similarly investigated. These characteristics, taken together with the atypical transporter inventories, the presence of many alternative methods of energy acquisition (e.g. CO, light), and the periodic abundance of HIMB11 in Kaneohe Bay, suggest that stain HIMB11 is an opportunist in the environment, persisting on relatively few reduced substrates and alternative energy metabolism until conditions arise that are favorable for rapid growth (e.g. a phytoplankton bloom). Consistent with other members of this lineage is the potential for HIMB11 to play an important role in the cycling of the climatically important gases DMS, CO, and CO2, warranting further study in both the laboratory and field.

Acknowledgements

We thank the entire C-MORE staff and visiting scientists for support and instruction during the 2011 Summer Course in Microbial Oceanography. Dr. Mary Ann Moran at the University of Georgia provided invaluable instruction on Roseobacter genomics and bioinformatic analyses. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which funded the sequencing of this genome. Annotation was performed as part of the 2011 C-MORE Summer Course in Microbial Oceanography (http://cmore.soest.hawaii.edu/summercourse/2011/index.htm), with support by the Agouron Institute, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the University of Hawaii and Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), and the Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education (C-MORE), a National Science Foundation-funded Science and Technology Center (award No. EF0424599).

Abbreviations:

- DMSP - Dimethylsulfoniopropionate

DMS - dimethylsulfide, AanP - aerobic anoxygenic phototroph, COG - Clusters of Orthologous Groups, PGC -photosynthesis gene cluster, BLUF - blue-light using flavin adenine nucleotide, ABC - ATP-binding cassette, TRAP - tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic, DMTs - drug/metabolite transporters

References

- 1.González JM, Simó R, Massana R, Covert JS, Casamayor EO, Pedrós-Alió C, Moran MA. Bacterial community structure associated with a dimethylsulfoniopropionate-producing North Atlantic algal bloom. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000; 66:4237-4246 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4237-4246.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki MT, Béjà O, Taylor LT, DeLong EF. Phylogenetic analysis of ribosomal RNA operons from uncultivated coastal marine bacterioplankton. Environ Microbiol 2001; 3:323-331 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giebel HA, Brinkhoff T, Zwisler W, Selje N, Simon M. Distribution of Roseobacter RCA and SAR11 lineages and distinct bacterial communities from the subtropics to the Southern Ocean. Environ Microbiol 2009; 11:2164-2178 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selje N, Simon M, Brinkhoff T. A newly discovered Roseobacter cluster in temperate and polar oceans. Nature 2004; 427:445-448 10.1038/nature02272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran MA, Belas R, Schell MA, González JM, Sun F, Sun S, Binder BJ, Edmonds J, Ye W, Orcutt B, et al. Ecological genomics of marine roseobacters. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73:4559-4569 10.1128/AEM.02580-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slightom RN, Buchan A. Surface colonization by marine roseobacters: integrating genotype and phenotype. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:6027-6037 10.1128/AEM.01508-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo H, Löytynoja A, Moran MA. Genome content of uncultivated marine roseobacters in the surface ocean. Environ Microbiol 2011; 14:41-51 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran MA, Buchan A, González JM, Heidelberg JF, Whitman WB, Kiene RP, Henriksen JR, King GM, Belas R, Fuqua C, et al. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature 2004; 432:910-913 10.1038/nature03170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton RJ, Griffin LE, Bowles KM, Meile C, Gifford S, Givens CE, Howard EC, King E, Oakley CA, Reisch CR, et al. Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J 2010; 4:784-798 10.1038/ismej.2009.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Jørgensen NOG, May N. Seasonal cycling of putrescine and amino acids in relation to biological production in a stratified coastal salt pond. Biogeochemistry 1995; 29:131-157 10.1007/BF00000229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiene RP, Linn LJ. The fate of dissolved dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in seawater: tracer studies using 35S-DMSP. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2000; 64:2797-2810 10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00399-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng H, Belas R. Molecular mechanisms underlying roseobacter-phytoplankton symbioses. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2010; 21:332-338 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran MA, González JM, Kiene RP. Linking a bacterial taxon to sulfur cycling in the sea: studies of the marine Roseobacter group. Geomicrobiol J 2003; 20:375-388 10.1080/01490450303901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo SK, Huggett MJ, Eiler A, Rappé MS. Coastal bacterioplankton community dynamics in response to a natural disturbance. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e56207 10.1371/journal.pone.0056207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rappé MS, Connon SA, Vergin KL, Giovannoni SJ. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 2002; 418:630-633 10.1038/nature00917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, Euzeby J, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Ludwig W, Glöckner FO, Rosselló-Móra R. The All-Species Living Tree project: a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008; 31:241-250 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, Yadhukumar J, Buchner A, Lai T, Steppi S, Jobb G, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:1363-1371 10.1093/nar/gkh293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006; 22:2688-2690 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvestro D, Michalak I. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org Divers Evol 2012; 12:335-337 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkhoff T, Giebel HA, Simon M. Diversity, ecology, and genomics of the Roseobacter clade: a short overview. Arch Microbiol 2008; 189:531-539 10.1007/s00203-008-0353-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. [<jrn>]. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Zheng J, Fu Z, Nan P, Zhong Y, Lonardi S, Jiang T. Assignment of orthologous genes via genome rearrangement. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinformatics 2005; 2:302-315 10.1109/TCBB.2005.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TG. Family I. Rhodobacteraceae fam. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, 2005, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunliffe M. Correlating carbon monoxide oxidation with cox genes in the abundant marine Roseobacter clade. ISME J 2011; 5:685-691 10.1038/ismej.2010.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunliffe M. Physiological and metabolic effects of carbon monoxide oxidation in the model marine bacterioplankton Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:738-740 10.1128/AEM.02466-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner-Döbler I, Biebl H. Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu Rev Microbiol 2006; 60:255-280 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Q, Zhang R, Koblížek M, Boldareva EN, Yurkov V, Yan S, Jiao N. Diverse arrangement of photosynthetic gene clusters in aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e25050 10.1371/journal.pone.0025050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TG. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Validation List No 07. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TG. Class I. Alphaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TG. Order III. Rhodobacterales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TG. Family I. Rhodobacteraceae fam. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandon M. High-throughput isolation of pelagic marine bacteria from the coastal subtropical Pacific Ocean. MS thesis. Univ of Hawaii at Manoa. 2006:p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review http://img.jgi.doe.gov

- 41.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33:D121-D124 10.1093/nar/gki081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiene RP. Production of methanethiol from dimethylsulfoniopropionate in marine surface waters. Mar Chem 1996; 54:69-83 10.1016/0304-4203(96)00006-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sunda W, Kieber DJ, Kiene RP, Huntsman S. An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature 2002; 418:317-320 10.1038/nature00851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiene RP, Linn LJ, Bruton JA. New and important roles for DMSP in marine microbial communities. J Sea Res 2000; 43:209-224 10.1016/S1385-1101(00)00023-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiene RP, Linn LJ. Distribution and turnover of dissolved DMSP and its relationship with bacterial production and dimethylsulfide in the Gulf of Mexico. Limnol Oceanogr 2000; 45:849-861 10.4319/lo.2000.45.4.0849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoch DC. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate: its sources, role in the marine food web, and biological degradation to dimethylsulfide. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002; 68:5804-5815 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5804-5815.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tripp HJ, Kitner JB, Schwalbach MS, Dacey JWH, Wilhelm LJ, Giovannoni SJ. SAR11 marine bacteria require exogenous reduced sulphur for growth. Nature 2008; 452:741-744 10.1038/nature06776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moran MA, Reisch CR, Kiene RP, Whitman WB. Genomic insights into bacterial DMSP transformations. Annu Rev Mar Sci 2012; 4:523-542 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reisch CR, Moran MA, Whitman WB. Bacterial catabolism of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). Front Microbiol 2011; 2:172 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fuchs BM, Spring S, Teeling H, Quast C, Wulf J, Schattenhofer M, Yan S, Ferriera S, Johnson J, Glöckner FO, et al. Characterization of a marine gammaproteobacterium capable of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:2891-2896 10.1073/pnas.0608046104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mulligan C, Fischer M, Thomas GH. Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters in bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011; 35:68-86 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jack DL, Yang NMH, Saier M. The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur J Biochem 2001; 268:3620-3639 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]