Abstract

Leucobacter salsicius M1-8T is a member of the Microbacteriaceae family within the class Actinomycetales. This strain is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium and was previously isolated from a Korean fermented food. Most members of the genus Leucobacter are chromate-resistant and this feature could be exploited in biotechnological applications. However, the genus Leucobacter is poorly characterized at the genome level, despite its potential importance. Thus, the present study determined the features of Leucobacter salsicius M1-8T, as well as its genome sequence and annotation. The genome comprised 3,185,418 bp with a G+C content of 64.5%, which included 2,865 protein-coding genes and 68 RNA genes. This strain possessed two predicted genes associated with chromate resistance, which might facilitate its growth in heavy metal-rich environments.

Keywords: chromate resistance, Leucobacter salsicius, Microbacteriaceae

Introduction

The strain M1-8T (= KACC 21127T = JCM 16362T) is the type strain of the species Leucobacter salsicius [1], which was isolated from a Korean salt-fermented seafood known as “jeotgal” in Korean. The species epithet was derived from the Latin word salsicius, which means salty [1]. The genus Leucobacter was proposed in 1996 [2] and comprises a group of related Gram-positive, aerobic, non-motile, rod-shaped bacteria. Leucobacter strains have been recovered from a variety of ecological niches, including activated sludge from soil [3], wastewater [4-6], river sediments containing chromium [5], nematodes [7,8], food [1,9], potato plant phyllosphere [10], chironomid egg masses [11], air [12], soil [13], and feces [14]. Several Leucobacter strains have been reported to possess chromate resistance [1,4,11]. At present, there are 18 validly named Leucobacter species, but the only sequenced genomes in this genus were Leucobacter sp. UCD-THU [15] and L. chromiiresistens [16]. Among them, the highest resistance to chromate (up to 300 mM K2CrO4) was observed in L. chromiiresistens, in vivo [13]. However, no information has been generated on genes related to the mechanism of chromate resistance .

L. salsicius strain M1-8T has lower chromate resistance than L. chromiiresistens but it still exhibits moderate resistance (up to 10.0 mM Cr(VI)). Thus, the genomic analysis of L. salsicius M1-8T should help us to understand the molecular basis of adaptation to a chromium-contaminated environment. The present study determined the classification and features of Leucobacter salsicius strain M1-8T, as well as its genome sequence and gene annotations.

Classification and features

16S rRNA analysis

A representative genomic 16S rRNA gene of strain M1-8T was compared with those obtained using NCBI BLAST [17] with the default settings (only highly similar sequences). The most frequently occurring genera were Leucobacter (65.0%), unidentified bacteria (20.0%), Curtobacterium (6.0%), Microbacterium (5.0%), Leifsonia (2.0%), Subtercola (1.0%), and Zimmermannella (1.0%) (100 hits in total). The species with the Max score was Leucobacter exalbidus (AB514037), which had a shared identity of 99.0%.

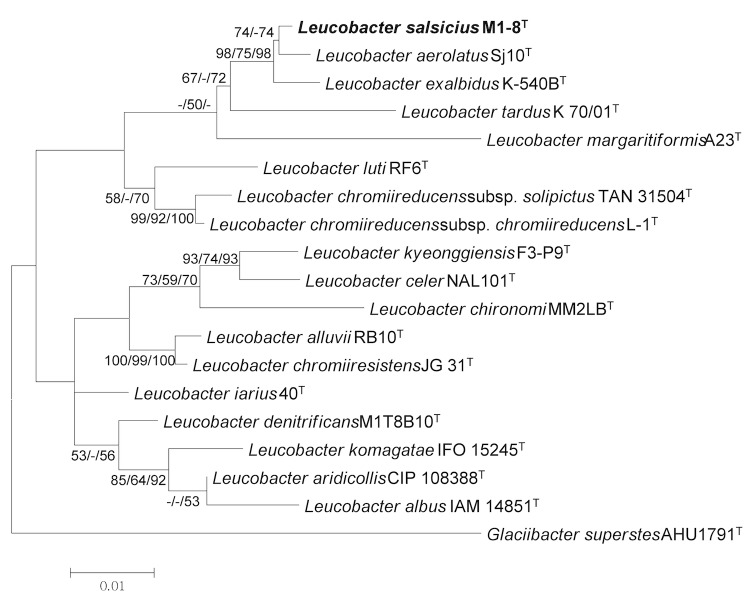

The multiple sequence alignment program CLUSTALW [18] was used to align the 16S rRNA gene sequences from M1-8T and related taxa. Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the aligned gene sequences using the maximum-likelihood, maximum-parsimony, and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 randomly selected bootstrap replicates using MEGA version 5 [19]. Strain M1-8T shared 99.1% nucleotide sequence similarity with L. aerolatus Sj10T, the closest validated Leucobacter species according to the phylogeny (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic position of L. salsicius in the 16S rRNA-based tree. The sequence of the single 16S rRNA gene copy found in the genome did not differ from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (GQ352403).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the position of Leucobacter salsicius relative to the type strains of other species within the genus Leucobacter, using Glaciibacter superstes AHU1791T as the outgroup. The sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW [18] and the phylogenetic tree was inferred from 1,390 aligned characteristics of the 16S rRNA gene sequence using the maximum-likelihood (ML) algorithm [20] with MEGA5 [19]. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. The numbers adjacent to the branches are the support values based on 1,000 ML bootstrap replicates [20] (left), 1,000 maximum-parsimony bootstrap replicates [21] (middle), and 1,000 neighbor-joining bootstrap replicates [22] (right), for values >50%.

Morphology and physiology

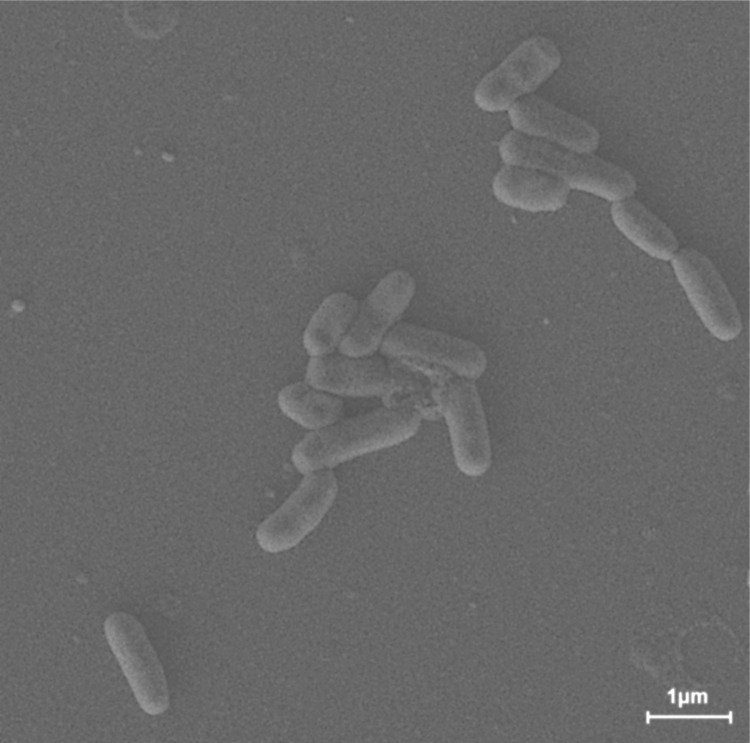

Strain M1-8T is classified as class Actinobacteria, order Actinomycetales, family Microbacteriaceae, genus Leucobacter (Table 1) [1]. The strain L. salsicius M1-8T was isolated from a Korean salt-fermented food that contains tiny shrimp (shrimp jeotgal). The cells of strain M1-8T were rod-shaped, 1.0–1.5 μm in length, and 0.4–0.5 μm in diameter (Figure 2). No flagella were observed. The colonies were cream in color and circular with entire margins on marine agar medium. Strain M1-8T was aerobic and Gram-positive (Table 1). Optimum growth was observed at 25–30°C, at pH 7.0–8.0, and in the presence of 0–4% (w/v) NaCl. The tolerance of Cr (VI) was observed at up to 10.0 mM K2CrO4. The physiological characteristics, such as the growth substrates of M1-8T, were described in detail in a previous study [1].

Table 1. Classification and general features of L. salsicius M1-8T according to the Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence (MIGS) recommendations [23].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [24] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [25] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [26] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [26-29] | ||

| Family Microbacteriaceae | TAS [26,27,30,31] | ||

| Genus Leucobacter | TAS [2] | ||

| Species Leucobacter salsicius | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain M1-8T | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | Non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | Not reported | ||

| Temperature range | Mesophile | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 25–30°C | TAS [1] | |

| pH | pH 7–8 | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | Heterotroph | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | Not reported | ||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Fermented food | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Halotolerant | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Not reported | NAS |

| Isolation | Fermented food (Shrimp jeotgal, a Korean salt-fermented food) | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | South Korea | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection date | May 2009 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported |

The evidence codes are as follows. TAS: traceable author statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature). NAS: non-traceable author statement (i.e., not observed directly in a living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property of the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are derived from the Gene Ontology project [32].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of Leucobacter salsicius M1-8T, which was obtained using a SUPRA VP55 (Carl Zeiss) at an operating voltage of 15 kV. The scale bar represents 1 μm.

Chemotaxonomy

The peptidoglycan hydrolysate from strain M1-8T contained alanine, 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (DAB), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamic acid, and glycine. The predominant fatty acids (>10% of the total) in M1-8T were anteiso-C15:0 (63.6%), anteiso- C17:0 (16.7%), and iso-C16:0 (14.2%). The polar lipid profile of strain M1-8T contained diphosphatidylglycerol and an unknown glycolipid. The major menaquinone in M1-8T was MK-11 and the minor menaquinones were MK-10 and MK-7.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

L. salsicius strain M1-8T was selected for genome sequencing based on its environmental potential and is part of the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No.PJ008208). The genome sequence was deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession number AOCN00000000 and the genome project was deposited in the Genomes On Line Database [33] under Gi21829. The sequencing and annotation were performed by ChunLab Inc., South Korea. A summary of the project information and the associations with “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) [34] are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Improved high-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 454 PE library (8 kb insert size), Illumina PE library (150 bp) |

| MIGS-28.2 | Number of reads | 4,157,212 sequencing reads |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | PacBio RS, Illumina GAii, 454-GS-FLX-Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 189.78 × Illumina; 7.96 × pyrosequence; 15.88 × PacBio |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Roche gsAssembler version 2.6, CLCbio CLC Genomics Workbench version 5.0 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene-calling method | Prodigal 2.5 |

| INSDC ID | AOCN01000000 | |

| GenBank Date of Release |

April 3, 2013 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi21829 | |

| NCBI project ID | 175945 | |

| Database: IMG | 2526164546 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | KACC 21127T, JCM 16362T |

| Project relevance | Environmental and biotechnological |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

L. salsicius strain M1-8T was cultured aerobically in marine agar medium at 30°C. Genomic DNA was extracted using a G-spin DNA extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology), according to the standard protocol recommended by the manufacturer.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of an Illumina Hiseq system with a 150 base pair (bp) paired-end library, a 454 Genome Sequencer FLX Titanium system (Roche) with an 8 kb paired-end library, and a PacBio RS system (Pacific Biosciences). The Illumina reads were assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench ver. 5.0. The initial assembly was converted for the CLC Genomics Workbench by constructing fake reads from the consensus to collect the read pairs in the Illumina paired-end library. The 454 paired-end reads were assembled with Illumina data using gsAssembler ver. 2.6 (Roche) and the PacBio sequences were clustered into overlapping assembled data. CodonCode Aligner and CLC Genomics Workbench 5.0 were used for sequence assembly and quality assessment in the subsequent finishing process. The Illumina (189.78-fold coverage; 4,003,590 reads), PacBio (88-fold coverage; 23,441 reads), and 454 sequencing (7.96-fold coverage; 130,181 reads) platforms provided 213.62 × coverage (total 4,157,212 sequencing reads) of the genome. The final assembly identified one scaffold that included 28 contigs.

Genome annotation

The genes in the assembled genome were predicted using Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform as part of the DOE-JGI genome annotation pipeline [35], followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline. Comparisons of the predicted ORFs using the SEED [36], NCBI COG [37], Ez-Taxon-e [38], and Pfam [39] databases were conducted during gene annotation. Additional gene prediction analyses and functional annotation were performed with the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server databases [40] and the gene-caller GLIMMER 3.02. RNAmer 1.2 [41] and tRNAscan-SE 1.23 [42] were used to identify rRNA genes and tRNA genes, respectively. The CLgenomicsTM 1.06 (ChunLab) was used to visualize the genomic features.

Genome properties

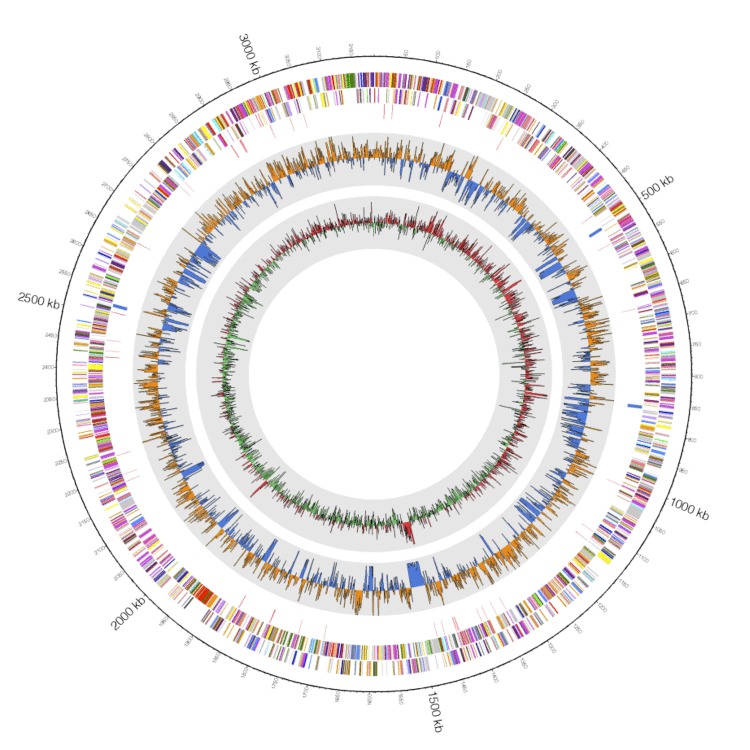

The genome comprised a circular chromosome with a length of 3,185,418 bp and a G+C content of 64.5% (Figure 3 and Table 3). Of the 2,933 predicted genes, 2,865 were protein-coding genes and 68 were RNA genes (three 5S rRNA genes, three 16S rRNA genes, three 23S rRNA genes, 51 predicted tRNA genes, and eight miscRNA genes). The majority of the protein-coding genes (2,275 genes; 77.6%) was assigned putative functions, while the remainder was annotated as hypothetical proteins (182 genes). The genome properties and statistics are summarized in Table 3. The distributions of genes among the COGs functional categories are shown in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Graphical map of the largest scaffold. From the outside to the center: genes on the reverse strand (colored according to the COGs categories), genes on the forward strand (colored according to the COGs categories), and RNA genes (tRNAs in red and rRNAs in blue). The inner circle shows the GC skew, where yellow indicates positive values and blue indicates negative values. The GC ratio is shown in red/green, which indicates positive/negative, respectively.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,185,418 | 100 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,905,046 | 91.20 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,054,445 | 64.5 |

| Total genes | 2,933 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 68 | 2.32 |

| rRNA operons | 3 | 0.31 |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,865 | 97.68 |

| Genes with predicted functions | 2,275 | 77.57 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 2,357 | 80.36 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,210 | 75.35 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2331 | 79.47 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 195 | 6.65 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 784 | 26.73 |

aThe totals are based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein-coding genes in the annotated genome.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with general COGs functional categories.

| Code | Value | % agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 156 | 6.38 | Translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis |

| A | 4 | 0.16 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 218 | 8.91 | Transcription |

| L | 167 | 6.83 | Replication, recombination, and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.04 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 21 | 0.86 | Cell cycle control, cell division, and chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 40 | 1.64 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 100 | 4.09 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 112 | 4.58 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 0 | 0.00 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.04 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 32 | 1.31 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 69 | 2.82 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones |

| C | 131 | 5.36 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 129 | 5.27 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 315 | 12.88 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 74 | 3.03 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 101 | 4.13 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 81 | 3.31 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 154 | 6.30 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 51 | 2.09 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism |

| R | 307 | 12.55 | General function prediction only |

| S | 182 | 7.42 | Function unknown |

| - | 723 | 24.65 | Not in COGs |

aThe total is based on the total number of protein-coding genes in the annotated genome.

Insights from the genome sequence

Leucobacter salsicius M1-8T and Leucobacter members, such as L. chromiireducens, L. aridicollis, L. luti, and L. alluvii, have been shown to possess chromate resistance in previous studies, while Zhu et al. reported the reduction of chromate by Leucobacter sp. [43]. In the present study, the genome analysis of Leucobacter salsicius M1-8T detected two copies of chromate transport protein A (ChrA), which is a membrane protein that confers heavy metal tolerance via chromate ion efflux from the cytoplasm. Potentially, this gene is a key feature that allows Leucobacter to adapt to chromate-contaminated environments. The genome sequence of L. salsicius M1-8T should provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms that underlie chromium tolerance and it may facilitate the development of biotechnological applications to improve chromium-contaminated field sites.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Seong Woon Roh and his team members for help with SEM analysis (Jeju Center, Korea Basic Science Institute, Korea). This study was supported by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program under No. PJ008208, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Yun JH, Roh SW, Kim MS, Jung MJ, Park EJ, Shin KS, Nam YD, Bae JW. Leucobacter salsicius sp. nov., from a salt-fermented food. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:502-506 10.1099/ijs.0.021360-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi M, Weiss N, Schumann P, Yokota A. Leucobacter komagatae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new aerobic gram-positive, nonsporulating rod with 2,4-diaminobutyric acid in the cell wall. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1996; 46:967-971 10.1099/00207713-46-4-967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin YC, Uemori K, de Briel DA, Arunpairojana V, Yokota A. Zimmermannella helvola gen. nov., sp. nov., Zimmermannella alba sp. nov., Zimmermannella bifida sp. nov., Zimmermannella faecalis sp. nov. and Leucobacter albus sp. nov., novel members of the family Microbacteriaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:1669-1676 10.1099/ijs.0.02741-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morais PV, Francisco R, Branco R, Chung AP, da Costa MS. Leucobacter chromiireducens sp. nov, and Leucobacter aridicollis sp. nov., two new species isolated from a chromium contaminated environment. Syst Appl Microbiol 2004; 27:646-652 10.1078/0723202042369983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morais PV, Paulo C, Francisco R, Branco R, Paula Chung A, da Costa MS. Leucobacter luti sp. nov., and Leucobacter alluvii sp. nov., two new species of the genus Leucobacter isolated under chromium stress. Syst Appl Microbiol 2006; 29:414-421 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HJ, Lee SS. Leucobacter kyeonggiensis sp. nov., a new species isolated from dye waste water. J Microbiol 2011; 49:1044-1049 10.1007/s12275-011-1548-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muir RE, Tan MW. Leucobacter chromiireducens subsp. solipictus subsp. nov., a pigmented bacterium isolated from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, and emended description of L. chromiireducens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:2770-2776 10.1099/ijs.0.64822-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somvanshi VS, Lang E, Schumann P, Pukall R, Kroppenstedt RM, Ganguly S, Stackebrandt E. Leucobacter iarius sp. nov., in the family Microbacteriaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:682-686 10.1099/ijs.0.64683-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin NR, Kim MS, Jung MJ, Roh SW, Nam YD, Park EJ, Bae JW. Leucobacter celer sp. nov., isolated from Korean fermented seafood. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:2353-2357 10.1099/ijs.0.026211-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrendt U, Ulrich A, Schumann P. Leucobacter tardus sp. nov., isolated from the phyllosphere of Solanum tuberosum L. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2574-2578 10.1099/ijs.0.2008/001065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpern M, Shaked T, Pukall R, Schumann P. Leucobacter chironomi sp. nov., a chromate-resistant bacterium isolated from a chironomid egg mass. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:665-670 10.1099/ijs.0.004663-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin E, Lodders N, Jackel U, Schumann P, Kampfer P. Leucobacter aerolatus sp. nov., from the air of a duck barn. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:2838-2842 10.1099/ijs.0.021303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturm G, Jacobs J, Sproer C, Schumann P, Gescher J. Leucobacter chromiiresistens sp. nov., a chromate-resistant strain. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:956-960 10.1099/ijs.0.022780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weon HY, Anandham R, Tamura T, Hamada M, Kim SJ, Kim YS, Suzuki K, Kwon SW. Leucobacter denitrificans sp. nov., isolated from cow dung. J Microbiol 2012; 50:161-165 10.1007/s12275-012-1324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holland-Moritz HE, Bevans DR, Lang JM, Darling AE, Eisen JA, Coil DA. Draft Genome Sequence of Leucobacter sp. Strain UCD-THU (Phylum Actinobacteria). Genome Announc 2013; 1:e00325-e13 10.1128/genomeA.00325-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturm G, Buchta K, Kurz T, Rensing SA, Gescher J. Draft genome sequence of Leucobacter chromiiresistens, an extremely chromium-tolerant strain. J Bacteriol 2012; 194:540-541 10.1128/JB.06413-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994; 22:4673-4680 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol 1981; 17:368-376 10.1007/BF01734359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluge AG, Farris FS. Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst Zool 1969; 18:1-32 10.2307/2412407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 1987; 4:406-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stackebrandt ERF, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. List No. 53. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1995; 45:418-419 10.1099/00207713-45-2-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park YH, Suzuki K, Yim DG, Lee KC, Kim E, Yoon J, Kim S, Kho YH, Goodfellow M, Komagata K. Suprageneric classification of peptidoglycan group B actinomycetes by nucleotide sequencing of 5S ribosomal RNA. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1993; 64:307-313 10.1007/BF00873089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overbeek R, Begley T, Butler RM, Choudhuri JV, Chuang HY, Cohoon M, de Crecy-Lagard V, Diaz N, Disz T, Edwards R, et al. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33:5691-5702 10.1093/nar/gki866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28:33-36 10.1093/nar/28.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim OS, Cho YJ, Lee K, Yoon SH, Kim M, Na H, Park SC, Jeon YS, Lee JH, Yi H, et al. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2012; 62:716-721 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D211-D222 10.1093/nar/gkp985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 2008; 9:75 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu W, Yang X, Ma Z, Chai L. Reduction of high concentrations of chromate by Leucobacter sp. CRB1 isolated from Changsha, China. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2008; 24:991-996 10.1007/s11274-007-9564-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]