Abstract

Gluconobacter thailandicus strain NBRC 3257, isolated from downy cherry (Prunus tomentosa), is a strict aerobic rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium. Here, we report the features of this organism, together with the draft genome sequence and annotation. The draft genome sequence is composed of 107 contigs for 3,446,046 bp with 56.17% G+C content and contains 3,360 protein-coding genes and 54 RNA genes.

Keywords: Acetic acid bacteria, Gluconobacter

Introduction

Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are strictly aerobic Alphaproteobacteria. AAB are well known for their potential to incompletely oxidize a wide variety of sugars and alcohols. The genus Gluconobacter oxidizes a wide range of sugars, sugar alcohols, and sugar acids, and can accumulate a large amount of the corresponding oxidized products in the culture medium [1]. Thus, Gluconobacter strains are widely used for the industrial production of pharmaceutical intermediates, such as L-sorbose (vitamin C synthesis), 6-amino-L-sorbose (synthesis of the antidiabetic drug miglitol), and dihydroxyacetone (cosmetics for sunless tanning) [1]. Furthermore, the genera Acetobacter and Gluconacetobacter are widely used for the industrial production of vinegar because of their high ethanol oxidation ability [2].

To date, six genome sequences of Gluconobacter strains (Gluconobacter oxydans 621H, Gluconobacter oxydans H24, Gluconobacter oxydans WSH-003, Gluconobacter thailandicus NBRC 3255, Gluconobacter frateurii NBRC 101659, and Gluconobacter frateurii NBRC 103465) are available in the public databases [3-8]. These genomic data are useful for the experimental identification of unique proteins or estimation of the phylogenetic relationship among the related strains [9-11].

Gluconobacter thailandicus NBRC 3257 was isolated from downy cherry (Prunus tomentosa) in Japan [12], and identified based on its 16S rRNA sequence [13]. Here, we present a summary of the classification and a set of features of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257, together with a description of the draft genome sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

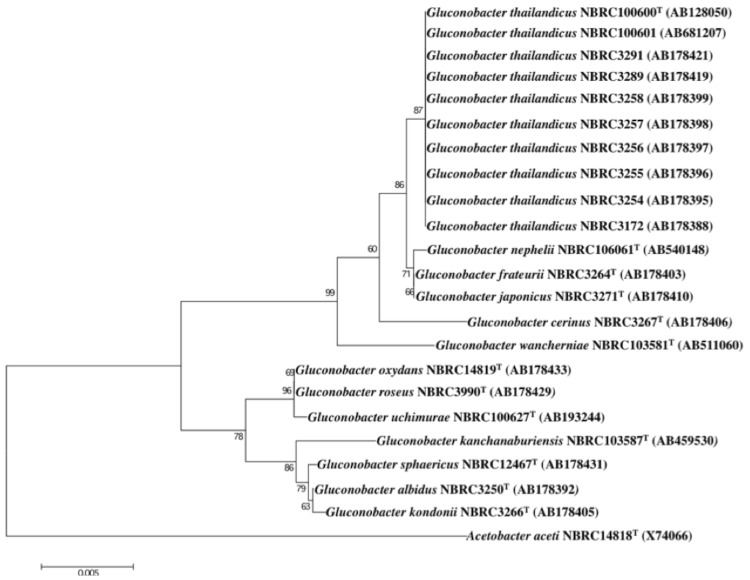

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 was compared to the 16S rRNA sequences of all known Gluconobacter species type strains. The 16S rRNA gene sequence identities between G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 and all other type strains of genus Gluconobacter species were 97.58-99.85%. Gluconobacter species (type strains) exhibiting the highest sequence identities to NBRC 3257 were Gluconobacter frateurii NBRC 3264T and Gluconobacter japonicas NBRC 3271T. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic relationships of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 to other Gluconobacter species in a 16S rRNA based tree. All the type strains and ten strains of G. thailandicus including NBRC 3257 were used for the analysis [13,17]. Based on this tree, genus Gluconobacter is divided into two sub-groups. Gluconobacter wanchamiae, Gluconobacter cerinus, G. frateurii, G. japonicas, Gluconobacter nephelli, and G. thailandicus are classified as clade 1. On the other hand, Gluconobacter kondonii, Gluconobacter sphaericus, Gluconobacter albidus, Gluconobacter kanchanaburiensis, Gluconobacter uchimurae, Gluconobacter roseus, and Gluconobacter oxydans belong to the clade 2. All ten G. thailandicus strains are closely related to each other, and the 16S rRNA sequences have 100% identities.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the phylogenetic position of Gluconobacter thailandicus NBRC 3257 relative to other type strains within the Gluconobacter. To construct the phylogenetic tree, these sequences were collected and nucleotide sequence alignment was carried out using CLUSTALW [14]. We used the MEGA version 5.05 package to generate phylogenetic trees based on 16S rRNA genes with the neighbor-joining (NJ) approach and 1,000 bootstrap replicates [15,16]. Acetobacter aceti NBRC14818 (X74066) was used as the outgroup.

Although ethanol oxidation ability is a typical feature of AAB, it is a critical feature that NBRC 3257 lacks the ability to oxidize ethanol because it is missing the cytochrome subunit of the alcohol dehydrogenase complex that functions as the primary dehydrogenase in the ethanol oxidase respiratory chain [18]. Despite its inability to oxidize ethanol, NBRC 3257 can efficiently oxidize many unique sugars and sugar alcohols, such as pentitols, D-sorbitol, D-mannitol, glycerol, meso-erythritol, and 2,3-butanediol [19]. Thus, G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 has unique characteristic features and the potential for the industrial production of many different oxidized products useful as drug intermediates or commodity chemicals.

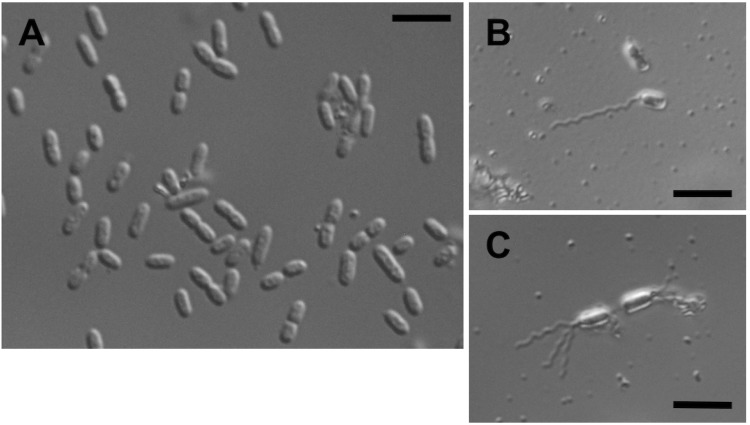

G. thanilandicus NBRC 3257 is a strictly aerobic, mesophilic (temperature optimum ≈ 30˚C) organism. Differential interference contrast image of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 cells grown on mannitol medium (25 g of D-manntiol, 5 g of yeast extract, and 3 g of polypeptone per liter) are shown in Figure 2 (A). The cells have short-rod shape with 2.6 ± 0.6 (mean ± SD, n = 10) µm in cell length and 1.2 ± 0.1 (mean ± SD, n = 10) µm in cell width. The flagella stained by the modified Ryu method are shown in Figure 2 (B) and Figure 2 (C) [20]. Singly and multiply flagellated cells were observed frequently. The characteristic features are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Cell morphology and flagella of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257. (A) Differential interference contrast image of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 grown on mannitol medium. Bar, 5 µm. (B and C) Microscopic images of flagella stained by the modified Ryu method. Singly (B) and multiply (C) flagellated cells were observed. Bars, 5 µm.

Table 1. Classification and general features of Gluconobacter thailandicus NBRC 3257 according to the MIGS recommendations [21].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [22] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [23] | ||

| Class Alphaproteobacteria | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Order Rhodospirillales | TAS [26,27] | ||

| Family Acetobacteraceae | TAS [28,29] | ||

| Genus Gluconobacter | TAS [27,30,31] | ||

| Species Gluconobacter thailandicus | TAS [17,32] | ||

| Strain NBRC 3257 | TAS [23] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | NAS | |

| Sporulation | Not report | NAS | |

| Temperature range | Mesophilic | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 30°C | IDA | |

| Carbon source | Glucose and/or glycerol | IDA | |

| Energy source | Glucose and/or glycerol | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Free living | NAS |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Not report | NAS |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | Strict aerobes | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Fruits and Flower | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogenic | IDA |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Japan | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1954 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not report | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | Not report | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not report | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not report | NAS |

a Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [33]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property should have been directly observed, for the purpose of this specific publication, for a live isolate by one of the authors, or an expert or reputable institution mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

This genome was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position and 16S rRNA similarity to other members of the Gluconobacter genus. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession BASM00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, BASM01000000, and the sequence consists of 107 contigs. Table 2 presents the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [34].

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Illumina Paired-End library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina Hiseq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 358 × |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Velvet ver. 1.2.07 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Glimmer ver. 3.02 |

| DDBJ ID | BASM00000000 | |

| DDBJ Date of Release | August 08, 2013 | |

| Project relevance | Industrial |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The culture of strain NBRC 3257 used to prepare genomic DNA for sequencing was a laboratory stock and grown on ∆P medium [35] at 30°C with vigorous shaking. The genomic DNA was isolated as described in [36] with some modifications [35]. Three ml of culture broth was used to isolate DNA, and the final DNA preparation was dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM ethylendiamine tetraacetic acid solution. The purity, quality, and size of the genomic DNA preparation were analyzed by Hokkaido System Science Co., Ltd. (Japan) using spectrophotometer, agarose gel electrophoresis, and Qubit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the their guidelines.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 was sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencing platform by the paired-end strategy (2×100 bp). Paired-end genome fragments were annealed to the flow-cell surface in a cluster station (Illumina). A total of 100 cycles of sequencing-by-synthesis were performed and high-quality sequences were retained for further analysis. The final coverage reached 358-fold for an estimated genome size of 3.44 Mb. The sequence data from Illumina HiSeq 2000 were assembled with Velvet ver. 1.2.07 [37]. The final assembly yielded 107 contigs generating a genome size of 3.44 Mb. The contigs were ordered against the complete genome of G. oxydans 621H [3] using Mauve [38-40].

Genome annotation

Protein-coding genes (ORFs) of draft genome assemblies were predicted using Glimmer version 3.02 with a self-training dataset [41,42]. tRNAs and rRNAs were predicted using ARAGORN and RNAmmer, respectively [43,44]. Functional assignments of the predicted ORFs were based on a BLASTP homology search against two genome sequences, G. thailandicus NBRC 3255 and G. oxydans 621H, and the NCBI nonredundant (NR) database [45]. Functional assignment was also performed with a BLASTP homology search against Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases [46].

Genome properties

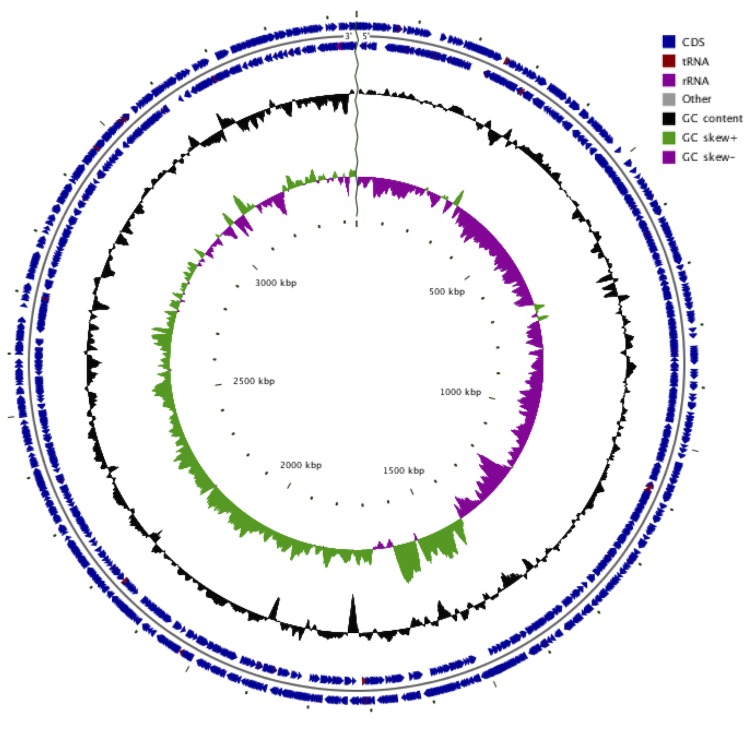

The genome of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 is 3,446,046 bp long (107 contigs) with a 56.17% G + C content (Table 3). Of the 3,414 predicted genes, 3,360 were protein coding genes, and 54 were RNAs (3 rRNA genes, and 51 tRNA genes). A total of 2,249 genes (66.93%) were assigned a putative function. The remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical genes. The properties and statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories is presented in Table 4. Of the 3,360 proteins, 2,669 (79%) were assigned to COG functional categories. Of these, 245 proteins were assigned to multiple COG categories. The most abundant COG category was "General function prediction only" (342 proteins) followed by "Amino acid transport and metabolism" (247 proteins), "Function unknown" (232 proteins), "Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis" (220 proteins), "Inorganic ion transport and metabolism" (210 proteins), and "Replication, recombination and repair" (201 proteins). The genome map of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 is illustrated in Figure 3, which demonstrates that the pattern of GC skew shifts from negative to positive along an ordered set of contigs with some exceptions. This suggests that the draft genome sequences were ordered almost exactly.

Table 3. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,446,046 | - |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,118,161 | 90.48 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,935,814 | 56.17 |

| Total genesb | 3,414 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 54 | 1.58 |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,360 | 98.42 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,669 | 78.17 |

a) The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 157 | 4.67 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.00 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 190 | 5.65 | Transcription |

| L | 201 | 5.98 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 28 | 0.83 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 44 | 1.31 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 92 | 2.74 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 220 | 6.55 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 43 | 1.28 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 2 | 0.06 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 95 | 2.83 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 120 | 3.57 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 170 | 5.06 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 194 | 5.77 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 247 | 7.35 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 89 | 2.65 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 129 | 3.84 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 91 | 2.71 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 210 | 6.25 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 64 | 1.90 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 342 | 10.18 | General function prediction only |

| S | 232 | 6.90 | Function unknown |

| - | 691 | 20.57 | No COG assignment |

| - | 245 | 7.29 | Multiple COG assignment |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of a simulated draft Gluconobacter thailandicus NBRC 3257 genome. The simulated genome is a set of contigs ordered against the complete genome of G. oxydans 621H [3] using Mauve [38-40]. The circular map was generated using CGview [47]. From the outside to the center: genes on forward strand, genes on reverse strand, GC content, GC skew.

Gene repertoire of G. thailandicus NBRC 3257 genome

Annotation of the genome indicated that NBRC 3257 has membrane-bound PQQ-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase, adhAB operon (locus_tag NBRC3257_1377 and NBRC3257_1378) and adh subunit III (NBRC3257_1024). A unique orphan gene of adh subunit I was also identified (NBRC3257_3117). The gene repertories of other membrane-bound PQQ dependent proteins were investigated. Homologous proteins of membrane-bound PQQ-dependent dehydrogenase (NBRC3257_0292), membrane-bound glucose dehydrogenase (PQQ) (NBRC3257_0371), PQQ-dependent dehydrogenase 4 (NBRC3257_0662), and PQQ-dependent dehydrogenase 3 (NBRC3257_1743), were identified. In addition, two paralogous copies of the PQQ-glycerol dehydrogenase sldAB operon (NBRC3257_0924 to NBRC3257_0925 and NBRC3257_1134 to NBRC3257_1135) were identified.

It has been thought that the respiratory chains of Gluconobacter species play key roles in respiratory energy metabolism [48-51]. Therefore, the gene repertoires of respiratory chains of NBRC 3257 were also investigated. Besides two type II NADH dehydrogenase homologs (NBRC3257_1995 and NBRC3257_2785) [51], a proton-pumping NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase operon (type I NADH dehydrogenase complex) (NBRC3257_2617 to NBRC3257_2629), a cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase cyoBACD operon (NBRC3257_2304 to NBRC3257_2307), and a cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase cioAB operon (NBRC3257_0388 to NBRC3257_0389) [48,49], were identified.

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by the Advanced Low Carbon Technology Research and Development Program (ALCA).

Abbreviations:

- DDBJ- DNA Data Bank of Japan

EMBL- European Molecular Biology Laboratory, NCBI- National Center for Biotechnology Information, AAB- Acetic Acid Bacteria, NJ- Neighbor joining, PQQ- Pyrroloquinoline quinone

References

- 1.Deppenmeier U, Hoffmeister M, Prust C. Biochemistry and biotechnological applications of Gluconobacter strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2002; 60:233-242 10.1007/s00253-002-1114-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sievers M, Teuber M. The microbiology and taxonomy of Acetobacter europaeus in commercial vinegar production. J Appl Microbiol 1995; 79:84-95 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prust C, Hoffmeister M, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Fricke WF, Ehrenreich A, Gottschalk G, Deppenmeier U. Complete genome sequence of the acetic acid bacterium Gluconobacter oxydans. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23:195-200 10.1038/nbt1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge X, Zhao Y, Hou W, Zhang W, Chen W, Wang J, Zhao N, Lin J, Wang W, Chen M and others. Complete Genome Sequence of the Industrial Strain Gluconobacter oxydans H24. Genome Announc 2013;1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Gao L, Zhou J, Liu J, Du G, Chen J. Draft genome sequence of Gluconobacter oxydans WSH-003, a strain that is extremely tolerant of saccharides and alditols. J Bacteriol 2012; 194:4455-4456 10.1128/JB.00837-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsutani M, Kawajiri E, Yakushi T, Adachi O, Matsushita K. Draft Genome Sequence of Dihydroxyacetone-Producing Gluconobacter thailandicus Strain NBRC 3255. Genome Announc 2013; 1:e0011813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattori H, Yakushi T, Matsutani M, Moonmangmee D, Toyama H, Adachi O, Matsushita K. High-temperature sorbose fermentation with thermotolerant Gluconobacter frateurii CHM43 and its mutant strain adapted to higher temperature. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012; 95:1531-1540 10.1007/s00253-012-4005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Umemura M, Koike H, Habe H. Draft Genome Sequence of Gluconobacter frateurii NBRC 103465, a Glyceric Acid-Producing Strain. Genome Announc 2013;1(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Matsutani M, Hirakawa H, Yakushi T, Matsushita K. Genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of Gluconobacter, Acetobacter, and Gluconacetobacter. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2011; 315:122-128 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsutani M, Hirakawa H, Saichana N, Soemphol W, Yakushi T, Matsushita K. Genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of differences in thermotolerance among closely related Acetobacter pasteurianus strains. Microbiology 2012; 158:229-239 10.1099/mic.0.052134-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters B, Mientus M, Kostner D, Junker A, Liebl W, Ehrenreich A. Characterization of membrane-bound dehydrogenases from Gluconobacter oxydans 621H via whole-cell activity assays using multideletion strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013; 97:6397-6412 10.1007/s00253-013-4824-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo K, Ameyama M. Carbohydrate metabolism by Acetobacter species. Part I. Oxidative activity for various carbohydrates. Bull Agric Chem Soc Jpn 1958; 22:369-372 10.1271/bbb1924.22.369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi M, Yukphan P, Yamada Y, Suzuki K, Sakane T, Nakagawa Y. Intrageneric structure of the genus Gluconobacter analyzed by the 16S rRNA gene and 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2006; 52:187-193 10.2323/jgam.52.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007; 23:2947-2948 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 2007; 24:1596-1599 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanasupawat S, Thawai C, Yukphan P, Moonmangmee D, Itoh T, Adachi O, Yamada Y. Gluconobacter thailandicus sp. nov., an acetic acid bacterium in the alpha-Proteobacteria. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2004; 50:159-167 10.2323/jgam.50.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita K, Nagatani Y, Shinagawa E, Adachi O, Ameyama M. Reconstitution of the ethanol oxidase respiratory chain in membranes of quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase-deficient Gluconobacter suboxydans subsp. alpha strains. J Bacteriol 1991; 173:3440-3445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adachi O, Fujii Y, Ghaly MF, Toyama H, Shinagawa E, Matsushita K. Membrane-bound quinoprotein D-arabitol dehydrogenase of Gluconobacter suboxydans IFO 3257: a versatile enzyme for the oxidative fermentation of various ketoses. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2001; 65:2755-2762 10.1271/bbb.65.2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodaka H, Armfield AY, Lombard GL, Dowell VR., Jr Practical procedure for demonstrating bacterial flagella. J Clin Microbiol 1982; 16:948-952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Validation List No. 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class I. Alphaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfennig N, Truper HG. Higher taxa of the phototrophic bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1971; 21:17-18 10.1099/00207713-21-1-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillis M, De Ley J. Intra- and intergeneric similarities of the ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistrons of Acetobacter and Gluconobacter. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:7-27 10.1099/00207713-30-1-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henrici AT. The Biology of Bacteria. In: Henrici AT (ed), The Biology of Bacteria, Second Edition, Heath and Co., Chicago, 1939, p. 1-494. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asai T. Taxonomic studies on acetic acid bacteria and allied oxidative bacteria isolated from fruits. A new classification of the oxidative bacteria. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi 1935; 11:674-708 10.1271/nogeikagaku1924.11.8_674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Ley J, Frateur J. Genus IV. Gluconobacter Asai 1935, 689; emend. mut. char. Asai, Iizuka and Komagata 1964, 100. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 251-253. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Validation List no. 103. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:983-985 10.1099/ijs.0.63767-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawai S, Goda-Tsutsumi M, Yakushi T, Kano K, Matsushita K. Heterologous overexpression and characterization of a flavoprotein-cytochrome c complex fructose dehydrogenase of Gluconobacter japonicus NBRC3260. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:1654-1660 10.1128/AEM.03152-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. Methods Enzymol 1963; 6:726-738 10.1016/0076-6879(63)06240-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18:821-829 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res 2004; 14:1394-1403 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rissman AI, Mau B, Biehl BS, Darling AE, Glasner JD, Perna NT. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2071-2073 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE 2010; 5:e11147 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007; 23:673-679 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salzberg SL, Delcher AL, Kasif S, White O. Microbial gene identification using interpolated Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res 1998; 26:544-548 10.1093/nar/26.2.544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:11-16 10.1093/nar/gkh152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29:22-28 10.1093/nar/29.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:537-539 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mogi T, Ano Y, Nakatsuka T, Toyama H, Muroi A, Miyoshi H, Migita CT, Ui H, Shiomi K, Omura S, et al. Biochemical and spectroscopic properties of cyanide-insensitive quinol oxidase from Gluconobacter oxydans. J Biochem 2009; 146:263-271 10.1093/jb/mvp067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miura H, Mogi T, Ano Y, Migita CT, Matsutani M, Yakushi T, Kita K, Matsushita K. Cyanide-insensitive quinol oxidase (CIO) from Gluconobacter oxydans is a unique terminal oxidase subfamily of cytochrome bd. J Biochem 2013; 153:535-545 10.1093/jb/mvt019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richhardt J, Luchterhand B, Bringer S, Buchs J, Bott M. Evidence for a key role of cytochrome bo3 oxidase in respiratory energy metabolism of Gluconobacter oxydans. J Bacteriol 2013; 195:4210-4220 10.1128/JB.00470-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsushita K, Ohnishi T, Kaback HR. NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductases of the Escherichia coli aerobic respiratory chain. Biochemistry 1987; 26:7732-7737 10.1021/bi00398a029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]