Abstract

Corynebacterium jeddahense sp. nov., strain JCBT, is the type strain of Corynebacterium jeddahense sp. nov., a new species within the genus Corynebacterium. This strain, whose genome is described here, was isolated from fecal flora of a 24-year-old Saudi male suffering from morbid obesity. Corynebacterium jeddahense is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic, nonsporulating bacillus. Here, we describe the features of this bacterium, together with the complete genome sequencing and annotation, and compare it to other member of the genus Corynebacterium. The 2,472,125 bp-long genome (1 chromosome but not plasmid) contains 2,359 protein-coding and 53 RNA genes, including 1 rRNA operon.

Keywords: Corynebacterium jeddahense, genome, culturomics, taxono-genomics

Introduction

Corynebacterium jeddahense strain JCBT (= CSUR P778 = DSM 45997) is the type strain of C. jeddahense sp. nov. This bacterium is a Gram-positive bacillus, non-spore-forming, strictly aerobic and non-motile that was isolated from the feces of a 24 year-old man living in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, who suffered from morbid obesity. This isolation was part of a “culturomics” study aiming at cultivating the maximum number of bacterial species from human feces [1,2].

The current classification of bacteria remains a matter of debate and relies on a combination of phenotypic and genomic characteristics [3]. Currently, more than 12,000 bacterial genomes have been sequenced [4], and we recently proposed an innovative concept for the taxonomic description of new bacterial species that integrates their genomic characteristics [5-35] as well as proteomic information obtained by MALDI-TOF-MS analysis [36].

In the present study, we present a summary classification and a set of features for Corynebacterium jeddahense sp. nov., strain JCBT (CSUR P778 = DSM 45997), including the description of its complete genome sequence and annotation. These characteristics support the circumscription of the species Corynebacterium jeddahense. The genus Corynebacterium was created in 1896 by Lehmann and Neumann and currently consists of mainly Gram-positive, non-spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria with a high DNA G+C content [37]. This genus belongs to the phylum Actinobacteria and currently includes more than 100 species with standing in nomenclature [38]. Members of the genus Corynebacterium are found in various environments including water, soil, sewage, and plants as well as in human normal skin flora and human or animals clinical samples. Some Corynebacterium species are well-established human pathogens while others are only considered as opportunistic pathogens. Corynebacterium diphteriae, causing diphtheria, is the most significant pathogen in this genus [39]. However, many Corynebacterium species including, among others, C. jeikeium, C. urealyticum, C. striatum, C. ulcerans and C. pseudotuberculosis, are recognized agents of bacteremias, endocarditis, urinary tract infections, and respiratory or wound infections [40].

Classification and features

A stool sample was collected from a 24-year-old man living in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, who suffered from morbid obesity (BMI=52). The patient gave a signed informed consent. The study and the assent procedure were approved by the Ethics Committees of the King Abdulaziz University, King Fahd medical Research Center, Saudi Arabia, under agreement number 014-CEGMR-2-ETH-P, and of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche 48, Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France, under agreement number 09-022. The patient was not taking any antibiotics at the time of stool sample collection and the fecal sample was kept at -80°C after collection. Strain JCBT (Table 1) was first isolated in July 2013 by cultivation on 5% sheep blood-enriched Columbia agar (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) in aerobic atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C after a 14-day preincubation of the stool sample in an aerobic blood culture bottle that also contained sterile rumen sheep fluid. Several other new bacterial species were isolated from this stool specimen using various culture conditions.

Table 1. Classification and general features of C. jeddahense strain JCBT according to the MIGS recommendations [41].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Bacteria | TAS [42] | ||

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [43] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [44] | ||

| Current classification | Order Actinomycetales | TAS [44-47] | |

| Family Corynebacteriaceae | TAS [44-46,48] | ||

| Genus Corynebacterium | TAS [45,49,50] | ||

| Species Corynebacterium jeddahense | IDA | ||

| Type strain JCBT | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | not motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non sporulating | IDA | |

| Temperature range | Mesophilic | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | IDA | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Unknown | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | IDA |

| Carbon source | Unknown | NAS | |

| Energy source | Unknown | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human gut | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Unknown | |

| Biosafety level | 2 | ||

| Isolation | Human feces | ||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | July 2013 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude Longitude |

21.422487 39.826184 |

IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Surface | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 0 m above sea level | IDA |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [51]. If the evidence is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

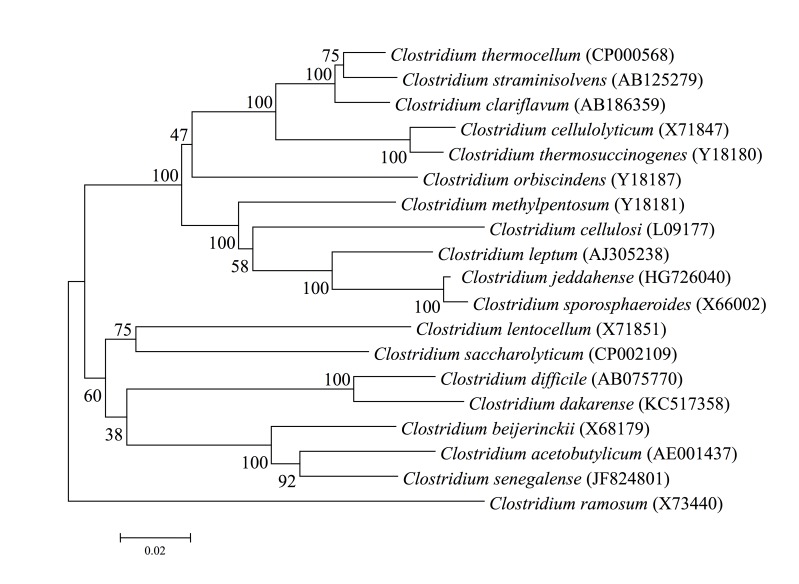

This strain exhibited a 96.8% nucleotide sequence similarity with C. coyleae, the phylogenetically most closely related Corynebacterium species with a validly published name (Figure 1). The similarity value was lower than the 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence threshold recommended by Stackebrandt and Ebers to delineate a new species without carrying out DNA-DNA hybridization [52], and was in the 82.9 to 99.60% range observed among members of the genus Corynebacterium with standing in the nomenclature [53].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Corynebacterium jeddahense strain JCBT relative to other type strains within the genus Corynebacterium. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic inferences obtained using the maximum-likelihood method in the MEGA software package. Numbers at the nodes are percentages of bootstrap values obtained by repeating the analysis 500 times to generate a majority consensus tree. Mycobacterium avium was used as outgroup. The scale bar represents 1% nucleotide sequence divergence.

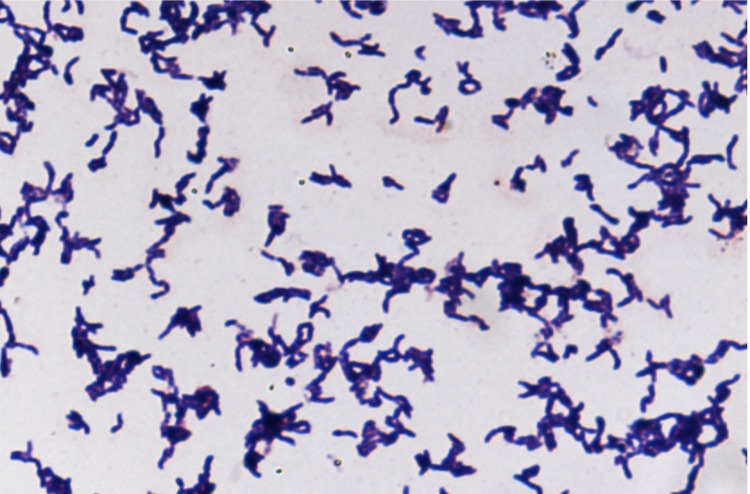

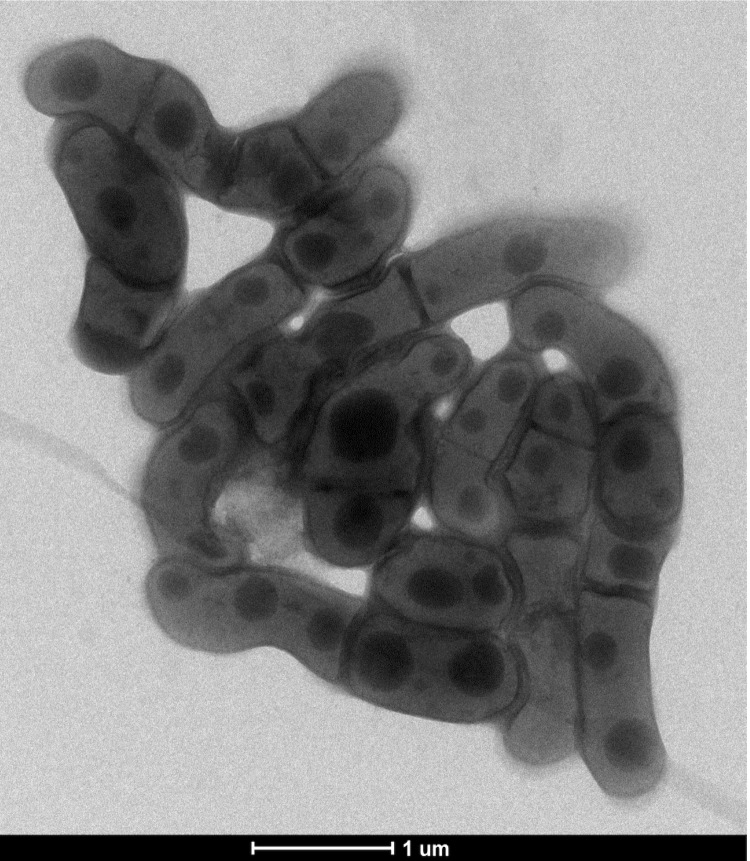

Four growth temperatures (25, 30, 37, 45°C) were tested. Growth occurred between 30 and 45°C on blood-enriched Columbia agar (BioMerieux), with the optimal growth being obtained at 37°C after 48 hours of incubation. Growth of the strain was tested under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions using GENbag Anaer and GENbag microaer systems, respectively (BioMerieux), and under aerobic conditions, with or without 5% CO2. Optimal growth was achieved aerobically. Weak cell growth was observed under microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions. The motility test was negative and the cells were not sporulating. Colonies were translucent and 1 mm in diameter on blood-enriched Columbia agar. Cells were Gram-positive rods (Figure 2). In electron microscopy, the bacteria grown on agar had a mean diameter and length of 0.63 and 1.22 μm, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Gram-stain of C. jeddahense strain JCBT

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrograph of C. jeddahense strain JCBT, taken using a Morgani 268D (Philips) at an operating voltage of 60kV. The scale bar represents 1 µm.

Strain JCBT was catalase positive and oxidase negative. Using an API CORYNE strip, a positive reaction was observed only for alkaline phosphatase and for catalase. Negative reactions were observed for reduction of nitrates, pyrolidonyl arylamidase, pyrazinamidase, β-glucuronidase, β-galactosidase, α-glucosidase N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, β-glucosidase, urease, gelatin hydrolysis and fermentation of glucose, ribose xylose, mannitol, maltose, lactose, saccharose and glycogen. Using the Api Zym system (BioMerieux), alkaline and acid phosphatases and Naphtol-AS-BI phosphohydrolase activities were positive, but esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), trypsin, α-chemotrypsin, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, α-glucosidase, N actetyl-β-glucosaminidase, leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystin arylamidase, α-mannosidase and α-fucosidase activities were negative.

Substrate oxidation and assimilation were examined with an API 50CH strip (BioMerieux) at 37°C. All reactions were negative, including fermentation of starch, glycogen, glycerol, erythritol, esculin ferric citrate, amygdalin, arbutin, salicin, L-arabinose, D-ribose, D-xylose, methyl β-D-xylopyranoside, D-galactose, D-glucose, D-fructose, D-mannose, L-rhamnose, D-mannitol, methyl α-D-xylopyranoside, methyl α-D-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, D-cellobiose, D-maltose, D-lactose, D-melibiose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, inulin, D-raffinose, D-lyxose, D-arabinose, L-xylose, D-adonitol, L-sorbose, dulcitol, inositol, D-sorbitol, D-melezitose, D-xylitol, gentiobiose, D-turanose, D-tagatose, D-fucose, L-fucose, D-arabitol, L-arabitol, potassium gluconate, and potassium 2-ketogluconate.

C. jeddahense is susceptible to amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, rifampin, gentamicin, doxycycline and vancomycin, but resistant to ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, eyrthromycin and metronidazole. When compared with representative species from the genus Corynebacterium, C. jeddahense strain JCBT exhibited the phenotypic differences detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Differential characteristics of C. jeddahense strain JCBT and closely related strains.

| C. jeddahense | C. pseudotuberculosis | C. efficiens | C. glutamicum | C. lipophiloflavum | C. coyleae | C. glaucum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter x length (µm) | 0.63 x 1.22 | 0.5-0.6 x 1.0-3.3 | 0.8-1.1 x 1.0-4.5 | 0.7-1 x 1-3 | 1-3 | NA | NA |

| Oxygen requirement | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic | Aero-anaerobic |

| Pigment production | None | Yellowish-white | Yellow | Pale yellow to yellow | Yellow | None | Light grey |

| Gram stain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Motility | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Endospore formation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Production of | |||||||

| Acid phosphatase | + | NA | NA | - | + | + | - |

| Alkaline phosphatase | + | v | - | - | + | + | + |

| Catalase | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oxidase | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pyrazinamidase | - | - | + | - | + | + | + |

| Nitrate reductase | - | V | + | + | - | - | - |

| Urease | - | + | V | + | W | - | - |

| Utilization of | |||||||

| Ribose | - | + | + | - | - | + | - |

| Mannose | - | + | + | + | NA | - | - |

| Mannitol | - | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Sucrose | - | + | + | - | - | + | |

| D-glucose | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| D-fructose | - | + | + | + | NA | + | NA |

| D-maltose | - | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| D-lactose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Habitat | Human gut | Sheep, infected gland, South America | Soil, Japan | Sewage, Japan | vaginal swab, Switzerland | Human blood | Cosmetic dye |

| Optimal temperature (oC) | 37°C | 37°C | 30-40°C | 25-37°C | 37°C | 37°C | 37°C |

+, Positive; –, negative; V, variable, W, weak reaction; NA, not available.

C. pseudotuberculosis strain CIP 102968T [54], C. efficiens YS-314T [55], C. glutamicum strain ATCC 13032T [56], C. lipophiloflavum strain DSM 44291T [57], C. coyleae strain DSM44184T [58] and C. glaucum strain IMMIB R-5091T [59].

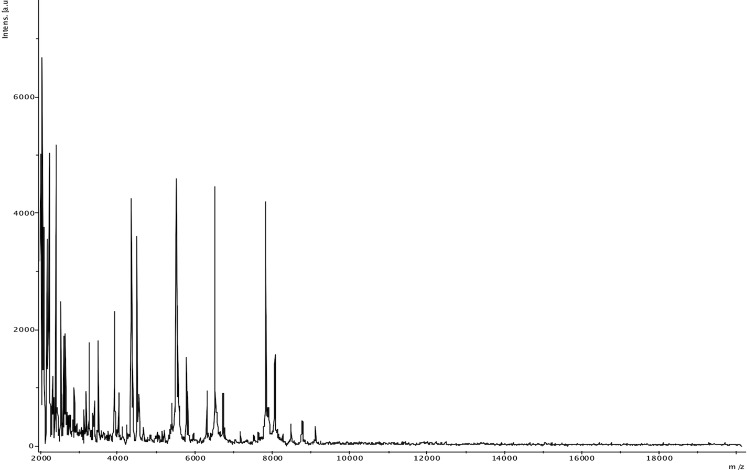

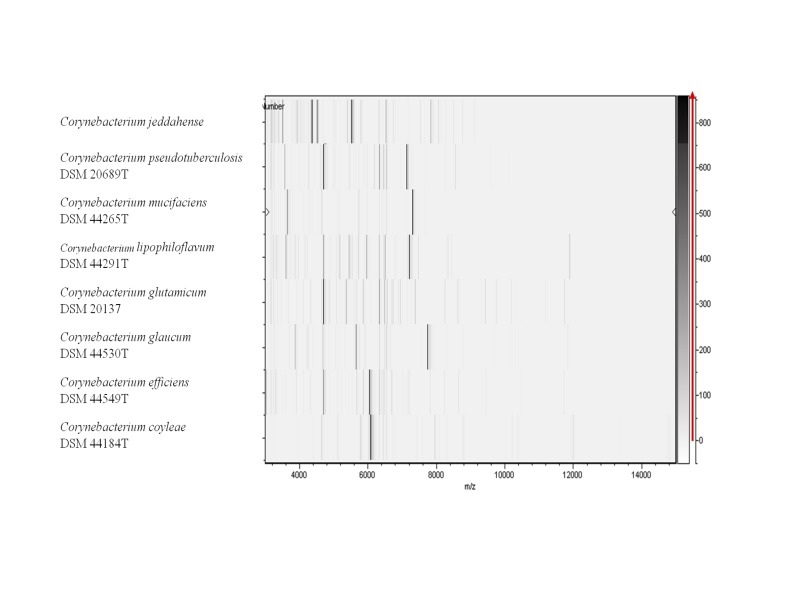

t (MALDI-TOF) MS protein analysis was carried out as previously described [36] using a Microflex spectrometer (Brüker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany). Twelve individual colonies were deposited on a MTP 384 MALDI-TOF target plate (Brüker). The twelve spectra were imported into the MALDI BioTyper software (version 2.0, Brüker) and analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of 4,706 bacteria, including 169 spectra from 69 validly named Corynebacterium species used as reference data in the BioTyper database. The score generated enabled the presumptive identification and discrimination of the tested species from those in a database: a score > 2 with a validated species enabled the identification at the species level; and a score < 1.7 did not enable any identification. For strain JCBT, no significant score was obtained, suggesting that our isolate was not a member of any known species (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Reference mass spectrum from C. jeddahense strain JCBT. Spectra from 12 individual colonies were compared and a reference spectrum was generated.

Figure 5.

Gel view comparing C. jeddahense strain JCBT (= CSUR P778 = DSM 45997) to other species from the genus Corynebacterium. The gel view displays the raw spectra of loaded spectrum files as a pseudo-electrophoretic gel. The x-axis records the m/z value. The left y-axis displays the running spectrum number originating from subsequent spectra loading. The peak intensity is expressed by a grey scale scheme code. The grey scale bar on the right y-axis indicates the relation between the shade of grey of the “band” and the peak intensity, in arbitrary units. Displayed species are indicated on the left.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, 16S rDNA similarity and phenotypic differences with members of the genus Corynebacterium and is part of a culturomics study of the human digestive flora aiming at isolating all bacterial species within human feces [2]. It was the 96th genome from a Corynebacterium species. The EMBL accession number is CBYN00000000and consists of 244 contigs. Table 3 shows the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [41].

Table 3. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One paired-end 454 3-kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 130 |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| BioProject ID | PRJEB4941 | |

| GenBank Accession number | CBYN00000000 | |

| GenBank date of release | February 12, 2014 | |

| MIGS-13 | Project relevance | Study of the human gut microbiome |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

C. jeddahense sp. nov strain JCBT (= CSUR P778 = DSM 45997) was grown aerobically on sheep blood-enriched Columbia agar medium at 37°C. Two petri dishes were spread and resuspended in 6x100µl of G2 buffer (EZI DNA Tissue Kit, Qiagen). A first mechanical lysis was performed using glass powder on the Fastprep-24 device (Sample Preparation System, MP Biomedicals, USA) using 2x20 second bursts. DNA was treated with 2.5µg/µL of lysozyme for 30 minutes at 37°C) and extracted using the BioRobot EZ 1 Advanced XL (Qiagen).The DNA was then concentrated and purified on a Qiamp kit (Qiagen). The DNA concentration, as measured by the Qubit assay with the high sensitivity kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), was 3.1ng/µl.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic DNA of C. jeddahense was sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) using both paired-end and mate-pair sequencing with the Nextera XT DNA sample and Nextera Mate Pair sample prep kits, respectively (Illumina).

To prepare the paired-end library, Genomic DNA was diluted 1:3 to obtain a 1ng/µl concentration. The “tagmentation” step fragmented and tagged the DNA with a mean size of 1.4kb. Then, a limited PCR amplification (12 cycles) completed the tag adapters and introduced dual-index barcodes. After purification on AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA), the library was then normalized on specific beads according to the Nextera XT protocol (Illumina). The pooled single strand library was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and paired end sequencing with dual index reads were performed in a single 39-hours run in 2x250-bp. Total information of 5.3Gb was obtained from a 574 K/mm2 cluster density with a cluster passing quality control filters of 95.4% (11,188,000 clusters). Within this run, the index representation for Corynebacterium jeddahense was determined to 6.2%. The 641,099 reads were filtered according to the read qualities.

The mate-pair library was prepared with 1µg of genomic DNA using the Nextera mate-pair Illumina guide. The genomic DNA sample was simultaneously fragmented and tagged with a mate-pair junction adapter. The profile of the fragmentation was validated on an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DNA 7500 labchip. The DNA fragments ranged in size from 1kb up to 10kb with a mean size of 2.6kb. No size selection was performed and 105ng of tagmented fragments were circularized. The circularized DNA was mechanically sheared to small fragments with an optimal at 409bp on the Covaris device S2 in microtubes (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA).The library profile was visualized on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer LabChip (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). After a denaturation step and dilution at 10pM, the library was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and sequencing run were performed in a single 42-hour run in a 2x250-bp. Total information of 3.9Gb was obtained from a 399 K/mm2 cluster density with a cluster passing quality control filters of 97.9% (7,840,000 clusters). Within this run, the index representation for Corynebacterium jeddahense was determined to 8.17%. The 626,585 reads were filtered according to the read qualities. Genome assembly was performed using Newbler (Roche).

Genome annotation

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [60] with default parameters. However, the predicted ORFs were excluded if they spanned a sequencing gap region. The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against GenBank [61] and Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases using BLASTP. The tRNAs and rRNAs were predicted using the tRNAScanSE [62] and RNAmmer [63] tools, respectively. Lipoprotein signal peptides and numbers of transmembrane helices were predicted using SignalP [64] and TMHMM [65], respectively. ORFans were identified if their BLASTP E-value was lower than 1e-3 for alignment length greater than 80 amino acids. If alignment lengths were smaller than 80 amino acids, we use an E-value of 1e-5. Such parameter thresholds have already been used in previous works to define ORFans.

Artemis [66] and DNA Plotter [67] were used for data management and visualization of genomic features, respectively. The Mauve alignment tool (version 2.3.1) was used for multiple genomic sequence alignments [68]. To estimate the mean level of nucleotide sequence similarity at the genome level between C. jeddahense and another 4 members of the Corynebacterium genus (Tables 6A and 6B), we used the Average Genomic Identity Of gene Sequences (AGIOS) home-made software [35]. Briefly, this software combines the Proteinortho software [69] for detecting orthologous proteins between genomes compared two by two, then retrieves the corresponding genes and determines the mean percentage of nucleotide sequence identity among orthologous ORFs using the Needleman-Wunsch global alignment algorithm.

Table 6. Genomic comparison of C. jeddahense and 4 other Corynebacterium species. †.

| Species | Strain | Genome accession number | Genome size (Mb) | G+C content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jeddahense | JCBT | CBYN00000000 | 2,472,125 | 67.2 |

| C. efficiens | YS-314T | NC_004369 | 3,147,090 | 62.9 |

| C. lipophiloflavum | DSM 44291T | ACHJ00000000 | 2,293,743 | 64.8 |

| C. glutamicum | ATCC 13032T | NC_003450 | 3,309,401 | 53.8 |

| C. pseudotuberculosis | CIP 52.97 | NC_017307 | 2,320,595 | 52.1 |

†Species name, strain, GenBank accession number, genome size and G+C content of compared genomes.

Genome properties

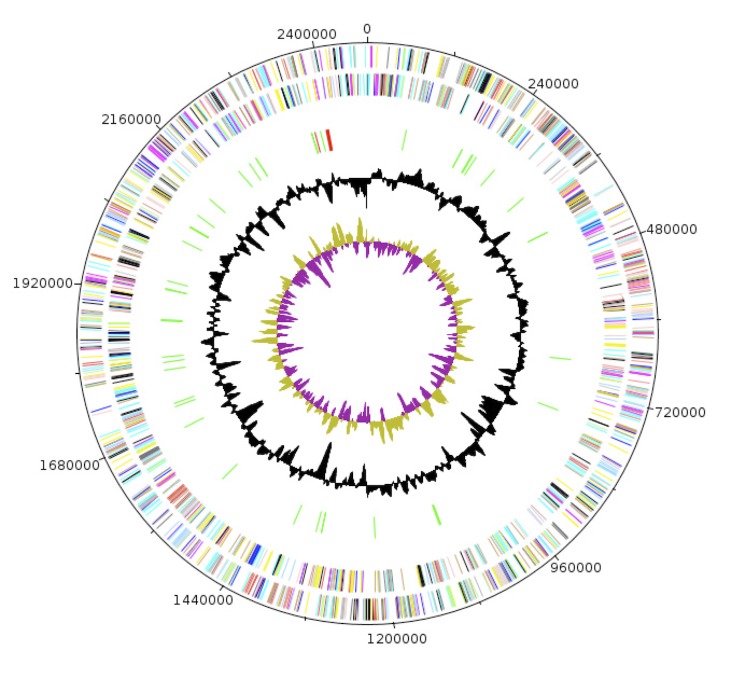

The genome C. jeddahense strain JCBT is 2,472,125 bp long (one chromosome, no plasmid) with a G+C content of 67.2% (Figure 6, Table 4). Of the 2,412 predicted chromosomal genes, 2,359 were protein-coding genes and 53 were RNAs. A total of 1,462 genes (60.61%) were assigned a putative function. Sixty-seven genes were identified as ORFans (2.77%) and the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 4. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Graphical circular map of the C. jeddahense strain JCBT genome. From the outside in, the outer two circles shows open reading frames oriented in the forward (colored by COG categories) and reverse (colored by COG categories) directions, respectively. The third circle marks the rRNA gene operon (red) and tRNA genes (green). The fourth circle shows the G+C% content plot. The inner-most circle shows GC skew, purple indicating negative values whereas olive for positive values.

Table 4. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the Chromosome.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,472,125 | |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,661,268 | 67.2 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 2,235,018 | 87.17 |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 2,412 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 53 | 2.2 |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,359 | 97.8 |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,462 | 60.61 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,636 | 67.82 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 187 | 7.75 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 629 | 26.1 |

a The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Table 5. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 149 | 6.18 | Translation |

| A | 1 | 0.04 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 132 | 5.47 | Transcription |

| L | 154 | 6.38 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 22 | 0.91 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 32 | 1.32 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 57 | 2.36 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 104 | 4.31 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 1 | 0.04 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 21 | 0.87 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 58 | 2.2 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 85 | 3.52 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 109 | 4.52 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 191 | 7.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 66 | 2.73 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 85 | 3.52 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 47 | 1.95 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 135 | 5.6 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 40 | 1.66 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 232 | 9.62 | General function prediction only |

| S | 145 | 6.01 | Function unknown |

| - | 776 | 32.17 | Not in COGs |

a The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Genome comparison of C. jeddahense with 4 other Corynebacterium genomes

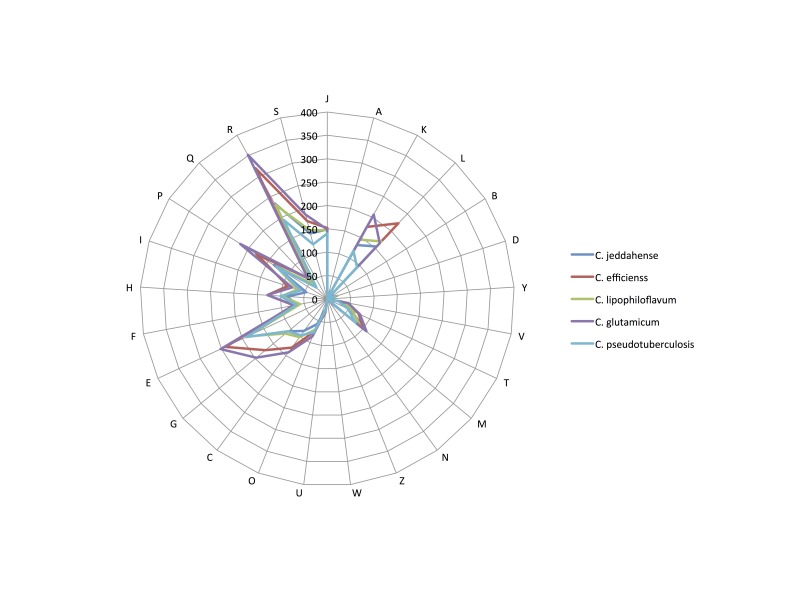

We compared the genome of C. jeddahense strain JCBT with those of C. efficiens YS-314T, C. lipophiloflavum strain DSM 44291T, C. glutamicum strain ATCC 13032T and C. pseudotuberculosis strain CIP 102968T (Table 6 and 7). The draft genome sequence of C. jeddahiense strain JCBT is larger than those of C. efficiens, C. lipophiloflavum and C. glutamicum (2.47, 2.26, 2.43 and 2.11 Mb, respectively), but smaller than that of C. pseudotuberculosis (2.48 Mb). The G+C content of C. jeddahense is larger than those of C. efficiens, C. lipophiloflavum, C. glutamicum and C. pseudotuberculosis (67.2, 62.9, 64.8, 53.8, and 52.1%, respectively). The gene content of C. jeddahense (2,359) is smaller than those of C. efficiens, C. lipophiloflavum and C. glutamicum (2,398, 2,371 and 2,993, respectively) but larger that of C. pseudotuberculosis (2,060). The distribution of genes into COG categories was similar but not identical in all four compared genomes (Figure 7).

Table 7. Genomic comparison of C. jeddahense and 4 other Corynebacterium species. †.

| C. jeddahense | C. efficiens | C. lipophiloflavum | C. glutamicum | C. pseudotuberculosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jeddahense | 2359 | 1,369 | 1,345 | 1,385 | 1,230 |

| C. efficiens | 71.81 | 2,938 | 1,449 | 1,605 | 1,381 |

| C. lipophiloflavum | 77.26 | 71.34 | 2,2371 | 1,465 | 1,285 |

| C. glutamicum | 68.12 | 75.04 | 68.43 | 2,993 | 1,400 |

| C. pseudotuberculosis | 66.44 | 67.93 | 66.7 | 68.47 | 2,060 |

†Numbers of orthologous proteins shared between genomes (upper right); AGIOS values (lower left); numbers of proteins per genome (bold).

Figure 7.

Distribution of functional classes of predicted genes in the genomes from C. jeddahense JCBT (colored in sea blue), C. efficiens YS-314T (blue), C. lipophiloflavum strain DSM 44291T (green), C. glutamicum strain ATCC 13032T (yellow) and C. pseudotuberculosis strain CIP 102968T (red) chromosomes, according to the clusters of orthologous groups of proteins.

In addition, C. jeddahense shared 1,369, 1,345, 1,385 and 1,230 orthologous genes with C. efficiens, C. lipophiloflavum, C. glutamicum and C. pseudotuberculosis, respectively. The AGIOS value ranged from 66.7 to 75.04 among compared Corynebacterium species except C. jeddahense. When compared to other species, the AGIOS value ranged from 66.44% with C. pseudotuberculosis to 77.26% with C. lipoflavum, thus confirming its new species status (Table 6B).

Conclusion

On the basis of phenotypic, phylogenetic and genomic analyses, we formally propose the creation of Corynebacterium jeddahense sp. nov., that contains the strain JCBT. The strain has been isolated from the fecal flora of a Saudi man suffering from morbid obesity. Several other as yet undescribed bacterial species were also cultivated from different fecal samples through diversification of culture conditions [5-35], thus suggesting that the human fecal flora of humans remains partially unknown.

Description of Corynebacterium jeddahense sp. nov.

Corynebacterium jeddahense (jed.dah.en'se N.L. neut. adj. Jeddah the name of the town in Saudi Arabia where the specimen was obtained).

Grows occurred between 30 and 45°C on blood-enriched Columbia agar (BioMerieux). Optimal growth obtained at 37°C in aerobic atmosphere. Weak growth obtained in microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions. Colonies are translucent and 1 mm in diameter. Not motile, not endospore-forming. Cells are Gram-positive rods and have a mean diameter and length of 0.63 and 1.22 μm, respectively. Catalase positive, oxidase negative. Using the API Coryne (BioMerieux) system, cells are alkaline phosphatase positive but negative for reduction of nitrates, pyrolidonyl arylamidase, pyrazinamidase, β-glucuronidase, β-galactosidase, α-glucosidase N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, β-glucosidase, urease, gelatin hydrolysis and fermentation of glucose, ribose xylose, mannitol, maltose, lactose, saccharose and glycogen. Using the Api Zym (BioMerieux) system, alkaline and acid phosphatases and Naphtol-AS-BI phosphohydrolase activities are positive, but esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), trypsin, α-chemotrypsin, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, α-glucosidase, N actetyl-β-glucosaminidase, leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystin arylamidase, α-mannosidase and α-fucosidase activities are negative. Using the API 50CH system (BioMerieux), fermentation of starch, glycogen, glycerol, erythritol, esculin ferric citrate, amygdalin, arbutin, salicin, L-arabinose, D-ribose, D-xylose, methyl β-D-xylopyranoside, D-galactose, D-glucose, D-fructose, D-mannose, L-rhamnose, D-mannitol, methyl α-D-xylopyranoside, methyl α-D-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, D-cellobiose, D-maltose, D-lactose, D-melibiose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, inulin, D-raffinose, D-lyxose, D-arabinose, L-xylose, D-adonitol, L-sorbose, dulcitol, inositol, D-sorbitol, D-melezitose, D- xylitol, gentiobiose, D-turanose, D-tagatose, D-fucose, L-fucose, D-arabitol, L-arabitol, potassium gluconate, and potassium 2-ketogluconate are negative. Cells are susceptible to amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, rifampicin, gentamicin, doxycycline and vancomycin but resistant to ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, eyrthromycin and metronidazole.

The G+C content of the genome is 67.2%. The 16S rRNA and genome sequences are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers HG726038 andCBYN00000000, respectively. The habitat of the microorganism is the human digestive tract. The type strain JCBT (= CSUR P778 = DSM 45997) was isolated from the fecal flora of a Saudi male who suffered from morbid obesity.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, under grant No. (1-141/1433 HiCi). This study was also funded by the Mediterranée-Infection Foundation. The authors thank the Xegen Company for automating the genomic annotation process.

References

- 1.Dubourg G, Lagier JC, Armougom F, Robert C, Hamad I, Brouqui P, Raoult D. The gut microbiota of a patient with resistant tuberculosis is more comprehensively studied by culturomics than by metagenomics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 32:637-645 10.1007/s10096-012-1787-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Million M, Hugon P, Pagnier I, Robert C, Bittar F, Fournous G, Gimenez G, Maraninchi M, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:1185-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tindall BJ, Rosselló-Móra R, Busse HJ, Ludwig W, Kämpfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:249-266 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Database GOLD.http://www.genomesonline.org/cgi-bin/GOLD/index.cgi

- 5.Roux V, Million M, Robert C, Magne A, Raoult D. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Oceanobacillus massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 9:370-384 10.4056/sigs.4267953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kokcha S, Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Million M, Leroy Q, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Bacillus timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:346-355 10.4056/sigs.2776064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagier JC, El Karkouri K, Nguyen TT, Armougom F, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:116-125 10.4056/sigs.2415480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra AK, Gimenez G, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Genome sequence and description of Alistipes senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:1-16 10.4056/sigs.2956294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Mishra AK, Nguyen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:315-324 10.4056/sigs.2685971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Clostridium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:386-395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:1-11 10.4056/sigs.2956294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Rivet R, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:70-81 10.4056/sigs.3056450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagier JC, Gimenez G, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Herbaspirillum massiliense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:200-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roux V, El Karkouri K, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Kurthia massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:221-232 10.4056/sigs.3206554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokcha S, Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Brevibacterium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:233-245 10.4056/sigs.3256677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramasamy D, Kokcha S, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Genome sequence and description of Aeromicrobium massiliense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:246-257 10.4056/sigs.3306717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagier JC, Ramasamy D, Rivet R, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Cellulomonas massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:258-270 10.4056/sigs.3316719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagier JC, Elkarkouri K, Rivet R, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Senegalemassilia anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 7:343-356 10.4056/sigs.3246665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra AK, Hugon P, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Robert C, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus obesi sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 7:357-369 10.4056/sigs.32766871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 7:370-381 10.4056/sigs.3366764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagier JC, El Karkouri K, Mishra AK, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Enterobacter massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 7:399-412 10.4056/sigs.3396830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugon P, Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Rivet R, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes obesi sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 7:427-439 10.4056/sigs.3336746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra AK, Hugon P, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus grossensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:320-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra AK, Hugon P, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Enorma massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the Family Coriobacteriaceae. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:290-305 10.4056/sigs.3426906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Gorlas A, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Bacillus massiliosenegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:264-278 10.4056/sigs.3496989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Dielma fastidiosa gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the Family Erysipelotrichaceae. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:336-351 10.4056/sigs.3567059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Genome sequence and description of Timonella senegalensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the suborder Micrococcinae. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:318-335 10.4056/sigs.3476977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra AK, Pfleiderer A, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Bacillus massilioanorexius sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:465-479 10.4056/sigs.4087826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hugon P, Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Nguyen TT, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Brevibacillus massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:1-14 10.4056/sigs.3466975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hugon P, Mishra AK, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus vaginalis. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:356-365 10.4056/sigs.2716452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hugon P, Ramasamy D, Robert C, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Kallipyga massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Clostridiales Incertae Sedis XI. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:500-515 10.4056/sigs.4047997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padhmanabhan R, Lagier JC, Dangui NPM, Michelle C, Couderc C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Megasphaera massiliensis. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 8:525-538 10.4056/sigs.4077819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mishra AK, Edouard S, Dangui NPM, Lagier JC, Caputo A, Blanc-Tailleur C, Ravaux I, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Nosocomiicoccus massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 9:205-219 10.4056/sigs.4378121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Pfleiderer A, Nguyen TT, Caputo A, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Holdemania massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2013; 9:395-409 10.4056/sigs.4628316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramasamy D, Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Padhmanabhan R, Rossi-Tamisier M, Sentausa E, Raoult D, Fournier PE. A polyphasic strategy incorporating genomic data for the taxonomic description of new bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2014; (In press). 10.1099/ijs.0.057091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:543-551 10.1086/600885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins MD, Smida J, Stackebrandt E. Phylogenetic Evidence for the Transfer of Caseobacter polymorphus (Crombach) to the Genus Corynebacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 1989; 39:7-9 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aravena-Román M, Sproer C, Siering C, Inglis T, Schumann P, Yassin AF. Corynebacterium aquatimens sp. nov., a lipophilic Corynebacterium isolated from blood cultures of a patient with bacteremia. Syst Appl Microbiol 2012; 35:380-384 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner KS, White JM, Lucenko I, Mercer D, Crowcroft NS, Neal S, Efstratiou A. Diphtheria in the postepidemic period, Europe, 2000-2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:217-225 10.3201/eid1802.110987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernard K. The genus corynebacterium and other medically relevant coryneform-like bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:3152-3158 10.1128/JCM.00796-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The road map to the manual. In Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology 2011; 119-166. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lehmann KB, Neumann R. Lehmann's Medizin, Handatlanten. X Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik., Fourth Edition, Volume 2, J.F. Lehmann, München, 1907, p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernard KA, Wiebe D, Burdz T, Reimer A, Ng B, Singh C, Schindle S, Pacheco AL. Assignment of Brevibacterium stationis (ZoBell and Upham 1944) Breed 1953 to the genus Corynebacterium, as Corynebacterium stationis comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Corynebacterium to include isolates that can alkalinize citrate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:874-879 10.1099/ijs.0.012641-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehmann KB, Neumann R. Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik, First Edition, J.F. Lehmann, München, 1896, p. 1-448. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today 2006; 33:152-155 [Google Scholar]

- 53.16S Youself database. (http://www mediterranee-infection com/article php?larub=152&titre= 16s-yourself)

- 54.Riegel P, Ruimy R, De Briel D, Prévost G, Jehl F, Christen R, Monteil H. Taxonomy of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and related taxa, with recognition of Corynebacterium ulcerans sp. nov. nom. rev. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1995; 126:271-276 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fudou R, Jojima Y, Seto A, Yamada K, Kimura E, Nakamatsu T, Hiraishi A, Yamanaka S. Corynebacterium efficiens sp. nov., a glutamic-acid-producing species from soil and vegetables. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1127-1131 10.1099/ijs.0.02086-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khinoshita S, Takayama S, Akita S. Taxonomical study of glutamic acid accumulating bacteria, Micrococcus glutamicus nov. sp. Bull Agric Chem Soc Jpn 1958; 22:176-185 10.1271/bbb1924.22.176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Funke G, Hutson RA, Hilleringmann M, Heizmann WR, Collins MD. Corynebacterium lipophiloflavum sp. nov. isolated from a patient with bacterial vaginosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1997; 150:219-224 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00118-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Funke G, Ramos CP, Collins MD. Corynebacterium coyleae sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:92-96 10.1099/00207713-47-1-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yassin AF, Kroppenstedt RM, Ludwig W. Corynebacterium glaucum sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:705-709 10.1099/ijs.0.02394-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prodigal. http://prodigal.ornl.gov

- 61.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Clark K, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D48-D53 10.1093/nar/gkr1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 2000; 16:944-945 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. DNA Plotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:119-120 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res 2004; 14:1394-1403 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lechner M, Findeiss S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:124 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]