Abstract

Clostridium indolis DSM 755T is a bacterium commonly found in soils and the feces of birds and mammals. Despite its prevalence, little is known about the ecology or physiology of this species. However, close relatives, C. saccharolyticum and C. hathewayi, have demonstrated interesting metabolic potentials related to plant degradation and human health. The genome of C. indolis DSM 755T reveals an abundance of genes in functional groups associated with the transport and utilization of carbohydrates, as well as citrate, lactate, and aromatics. Ecologically relevant gene clusters related to nitrogen fixation and a unique type of bacterial microcompartment, the CoAT BMC, are also detected. Our genome analysis suggests hypotheses to be tested in future culture based work to better understand the physiology of this poorly described species.

Keywords: Clostridium indolis, citrate, lactate, aromatic degradation, nitrogen fixation, bacterial microcompartments

Introduction

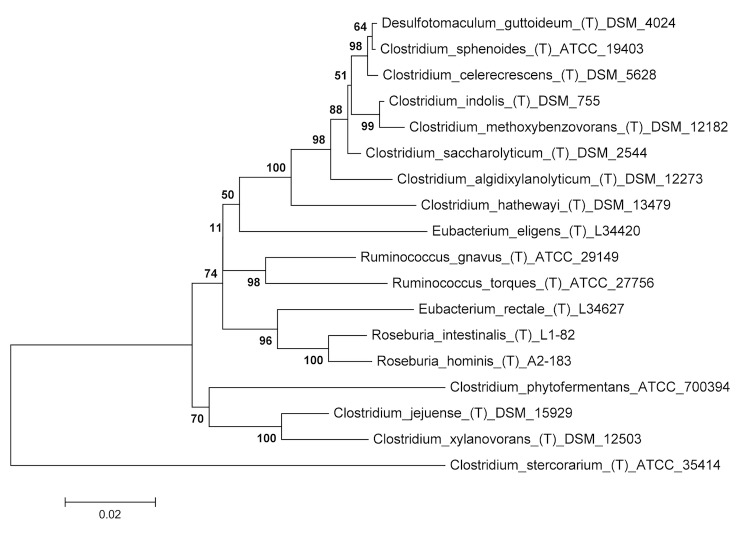

The C. saccharolyticum species group is a poorly described and taxonomically confusing clade in the Lachnospiraceae, a family within the Clostridiales that includes members of clostridial cluster XIVa [1]. This group includes C. indolis, C. sphenoides, C. methoxybenzovorans, C. celerecrescens, and Desulfotomaculum guttoideum, none of which are well studied (Figure 1). C. saccharolyticum has gained attention because its saccharolytic capacity was shown to be syntrophic with the cellulolytic activity of Bacteroides cellulosolvens in co-culture, enabling the conversion of cellulose to ethanol in a single step [6,7]. Members of this group, such as C. celerecrescens, are themselves cellulolytic [8], and others are known to degrade unusual substrates such as methylated aromatic compounds (C. methoxybenzovorans) [9], and the insecticide lindane (C. sphenoides) [10]. C. indolis was targeted for whole genome sequencing to provide insight into the genetic potential of this taxa that could then direct experimental efforts to understand its physiology and ecology.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences highlighting the position of Clostridium indolis relative to other type strains (T) within the Lachnospiraceae. The strains and their corresponding NCBI accession numbers (and, when applicable, draft sequence coordinates) for 16S rRNA genes are: Desulfotomaculum guttoideum strain DSM 4024T, Y11568; C. sphenoides ATCC 19403T, AB075772; C. celerecrescens DSM 5628T, X71848; C. indolis DSM 755T, Pending release by JGI: 1620643-1622056; C. methoxybenzovorans SR3, AF067965; C. saccharolyticum WM1T, NC_014376:18567-20085; C. algidixylanolyticum SPL73T, AF092549; C. hathewayi DSM 13479T, ADLN00000000: 202-1639; Eubacterium eligens L34420 T, L34420; Ruminococcus gnavus ATCC 29149T, X94967; R. torques ATCC 27756T, L76604; E. rectale L34627T; Roseburia intestinalis L1-82T, AJ312385; R. hominis A2-183T, AJ270482; C. jejuense HY-35-12T, AY494606; C. xylanovorans HESP1T, AF116920; C. phytofermentans ISDgT, CP000885: 15754-17276. The tree uses sequences aligned by MUSCLE, and was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method [2]. The optimal tree with the sum of branch lengths = 0.50791241 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown next to the branches [3]. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method [4] and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 5 [5]. C. stercorarium ATCC 35414T, CP003992: 856992-858513 was used as an outgroup.

Classification and features

The general features of Clostridium indolis DSM 755T are listed in Table 1. C. indolis DSM 755T was originally named for its ability to hydrolyze tryptophan to indole, pyruvate, and ammonia [23] in the classic Indole Test used to distinguish bacterial species. It has been isolated from soil [24], feces [25], and clinical samples from infections [27]. Despite its prevalence, C. indolis is not well characterized, and there are conflicting reports about its physiology. It is described as a sulfate reducer with the ability to ferment some simple sugars, pectin, pectate, mannitol, and galacturonate, and convert pyruvate to acetate, formate, ethanol, and butyrate [28]. According to this source, neither lactate nor citrate are utilized, however other studies demonstrate that fecal isolates closely related to C. indolis may utilize lactate [29], and that the type strain DSM 755T utilizes citrate [30]. It is unclear whether C. indolis is able to make use of a wider range of sugars or break down complex carbohydrates, however growth is reported to be stimulated by fermentable carbohydrates [28].

Table 1. Classification and general features of Clostridium indolis DSM 755T.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Bacteria | TAS [11] | ||

| Phylum Firmicutes | TAS [12-14] | ||

| Class Clostridia | TAS [15,16] | ||

| Current classification | Order Clostridiales | TAS [17,18] | |

| Family Lachnospiraceae | TAS [15,19] | ||

| Genus Clostridium | TAS [17,20,21] | ||

| Species Clostridium indolis | TAS [17,22] | ||

| Type strain DSM 755 | |||

| Gram stain | Negative | TAS [23,24] | |

| Cell shape | Rod | TAS [23,24] | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [23,24] | |

| Sporulation | Terminal, spherical spores | TAS [23,24] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophilic | TAS [23,24] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37oC | TAS [23,24] | |

| Carbon sources | Glucose, lactose, sucrose, mannitol, pectin, pyruvate, others | TAS [23,24] | |

| Terminal electron receptor | Sulfate | TAS [23,24] | |

| Indole test | Positive | TAS [23,24] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Isolated from soil, feces, wounds | TAS [24,25] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Inhibited by 6.5% NaCl | TAS [23,24] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | Anaerobic | TAS [23,24] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living and host associated TAS [24,25],9 | |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | No NAS | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Soil, feces TAS [24,25],9 |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [26].

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The genome was selected based on the relatedness of C. indolis DSM 755T to C. saccharolyticum, an organism with interesting saccharolytic and syntrophic properties. The genome sequence was completed on May 2, 2013, and presented for public access on June 3, 2013. Quality assurance and annotation done by DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) as described below. Table 2 presents a summary of the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [31].

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Improved Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Shotgun and long insert mate pair (Illumina), SMRTbellTM (PacBio) |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina and PacBio |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 759.7× (Illumina), 51.6× (PacBio) |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Velvet, AllpathsLG |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| Genome Database release | June 3, 2013 (IMB) | |

| Genbank ID | Pending release by JGI | |

| Genbank Date of Release | Pending release by JGI | |

| GOLD ID | Gi22434 | |

| Project relevance | Anaerobic plant degradation |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

C. indolis DSM 755T was cultivated anaerobically on GS2 medium as described elsewhere [32]. DNA for sequencing was extracted using the DNA Isolation Bacterial Protocol available through the JGI (http://www.jgi.doe.gov). The quality of DNA extracted was assessed by gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop (ThermoScientific, Wilmington, DE) according to the JGI recommendations, and the quantity was measured using the Quant-iTTM Picogreen assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as directed.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The draft genome of C. indolis was generated at the DOE Joint genome Institute (JGI) using a hybrid of the Illumina and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) technologies. An Illumina std shotgun library and long insert mate pair library was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform [33]. 16,165,490 reads totaling 2,424.8 Mb were generated from the std shotgun and 26,787,478 reads totaling 2,437.7 Mb were generated from the long insert mate pair library. A Pacbio SMRTbellTM library was constructed and sequenced on the PacBio RS platform. 99,448 raw PacBio reads yielded 118,743 adapter trimmed and quality filtered subreads totaling 330.2 Mb. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov. All raw Illumina sequence data was passed through DUK, a filtering program developed at JGI, which removes known Illumina sequencing and library preparation artifacts [34]. Filtered Illumina and PacBio reads were assembled using AllpathsLG (PrepareAllpathsInputs: PHRED 64=1 PLOIDY=1 FRAG COVERAGE=50 JUMP COVERAGE=25; RunAllpath- sLG: THREADS=8 RUN=std pairs TARGETS=standard VAPI WARN ONLY=True OVERWRITE=True) [35]. The final draft assembly contained 1 contig in 1 scaffold. The total size of the genome is 6.4 Mb. The final assembly is based on 2,424.6 Mb of Illumina Std PE, 2,437.6 Mb of Illumina CLIP PE and 330.2 Mb of PacBio post filtered data, which provides an average 759.7× Illumina coverage and 51.6× PacBio coverage of the genome, respectively.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [36], followed by a round of manual curation using GenePRIMP [9] for finished genomes and Draft genomes in fewer than 10 scaffolds. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. The tRNAScanSE tool [37] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNA genes were found by searches against models of the ribosomal RNA genes built from SILVA [38]. Other non–coding RNAs such as the RNA components of the protein secretion complex and the RNase P were identified by searching the genome for the corresponding Rfam profiles using INFERNAL [39]. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) platform [40] developed by the Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA, USA [41]. Information in the tables below reflects the gene information in the JGI annotation on the IMG website [40].

Genome properties

The genome of C. indolis DSM 755 consists of a 6,383,701 bp circular chromosome with GC content of 44.93% (Table 3). Of the 5,903 genes predicted, 5,802 were protein-coding genes, and 101 RNAs; 170 pseudogenes were also identified. 81.21% of genes were assigned with a putative function with the remaining annotated as hypothetical proteins. The genome summary and distribution of genes into COGs functional categories are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome of C. indolis DSM 755.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,383,701 | |

| DNA Coding region (bp) | 5,688,007 | 89.10 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,868,247 | 44.93 |

| Total genesb | 5,903 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 101 | 1.71 |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,802 | 98.29 |

| Protein-coding with function pred. | 4,794 | 81.21 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 4,527 | 76.69 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4,643 | 78.65 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 421 | 7.13 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,494 | 25.31 |

| Paralogous groups | 4,527 | 76.69 |

a) The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

b) Also includes 170 pseudogenes.

Table 4. Number of genes in C. indolis DSM 755 associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 184 | 3.57 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 531 | 10.30 | Transcription |

| L | 191 | 3.71 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 28 | 0.54 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 107 | 2.08 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 335 | 6.50 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 235 | 4.56 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 70 | 1.36 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 41 | 0.80 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 124 | 2.41 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 261 | 5.06 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 910 | 17.65 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 493 | 9.56 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 110 | 2.13 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 153 | 2.97 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 77 | 1.49 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 325 | 6.30 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 70 | 1.36 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 590 | 11.45 | General function prediction only |

| S | 319 | 6.19 | Function unknown |

| - | 1260 | 21.35 | Not in COGs |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

The genomes of C. indolis and its near relatives (C. saccharolyticum, C. hathewayi, and C. phytofermentans) have similar numbers of genes in each of the 25 broad COG categories (not shown), however differences exist in the type and distribution of genes in specific functional groups (Table 5), particularly those related to COG categories (G) Carbohydrate transport and metabolism, (C) Energy production and conversion, and (Q) Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism.

Table 5. Number of genes in each of the 25 general COG functional categoriesa found in C. indolis DSM 755T but not in closely related species.

| Code | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| J | 4 | Translation |

| A | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 5 | Transcription |

| L | 9 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 0 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 1 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 2 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 8 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 2 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 10 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 28 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 6 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 8 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 1 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 11 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 2 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 11 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 10 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 18 | General function prediction only |

| S | 21 | Function unknown |

a) Number of genes from a set of 158 genes not found in near relatives (C. saccharolyticum, C. phytofermentans, C. hathewayi) associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

Carbohydrate transport and metabolism

Plant biomass is a complex composite of fibrils and sheets of cellulose, hemicellulose, waxes, pectin, proteins, and lignin. Bacteria from soil and the gut generally possess a variety of genes to degrade and transport the diversity of substrates encountered in these plant-rich environments. The genome of C. indolis includes 910 genes (17.65% of total protein coding genes) in this COG group including glycoside hydrolases with the potential to degrade complex carbohydrates including starch, cellulose, and chitin (Table 6), as well as an abundance of carbohydrate transporters (Figure 2).

Table 6. Selected carbohydrate active genes in the C. indolis DSM 755T genome.

| Gene count | Product namea | Database IDb |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | Beta-glucosidase (GH-1) | EC:3.2.1.86 |

| 8 | Beta-galactosidase/ beta-glucuronidase (GH-2) |

EC:3.2.1.23 EC:3.2.1.25 EC:3.2.1.31 |

| 7 | Beta-glucosidase/ related glucosidases (GH-3) | EC:3.2.1.21 EC:3.2.1.52 |

| 14 | Alpha-galactosidases/ 6-phospho-beta-glucosidases (GH-4) |

EC:3.2.1.86 EC:3.2.1.122 EC:3.2.1.22 |

| 2 | Cellulase, endogluconase (GH-5) | EC:3.2.1.4 |

| 14 | Alpha-amylase | EC:3.2.1.10 EC:3.2.1.20 EC:2.4.1.7 EC:3.2.1.70 |

| 8 | Beta-xylosidase (GH 39) | EC:3.2.1.37 |

| 2 | Chitinase (GH 18) | EC:3.2.1.14 |

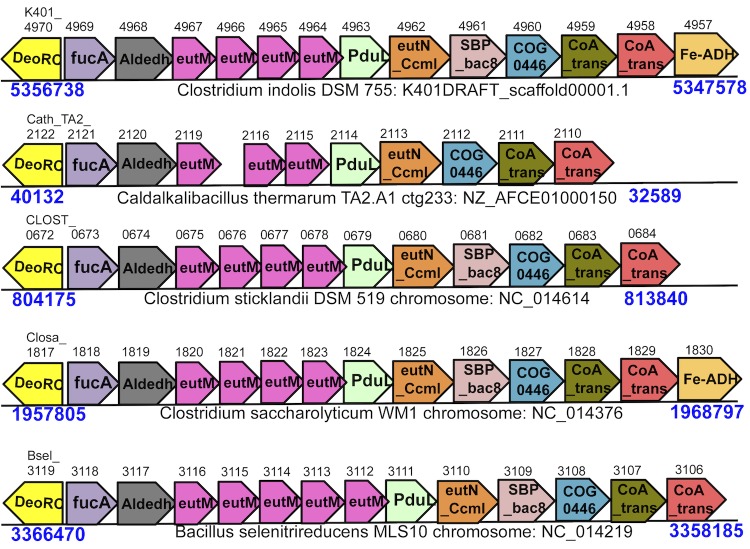

Figure 2.

Distribution of ABC and PTS transporters in the genomes of C. indolis and related genomes determined from Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) annotation [40] viewed based on (a) Total umber of COGS, and (b) Percentage of genes in the genome.

Almost 8% of the protein-coding genes in the genome of C. indolis were found to be associated with carbohydrate transport, represented by two main strategies. ABC (ATP binding cassette) transporters tend to carry oligosaccharides, and have less affinity for hexoses [43,44], while PTS (phosphotransferase system) transporters carry many different mono- and disaccharides, especially hexoses [45]. PTS systems provide a means of regulation via catabolite repression [46], and are thought to enable bacteria living in carbohydrate-limited environments to more efficiently utilize and compete for substrates [46]. Both C. indolis and its near relatives are more highly enriched in ABC than PTS transporters (Fig 2), however nearly a third of C. indolis and C. saccharolyticum transporters are PTS genes, suggesting a preference for hexoses, as well as an adaptation to more marginal environments. C. indolis also possesses ten genes associated with all three components of the TRAP-type C4-dicarboxylate transport system, which transports C4-dicarboxylates such as formate, succinate, and malate [47], as well as six putative malate dehydrogenases and two putative succinate dehydrogenases suggesting that C. indolis may have the potential to utilize both of these short chain fatty acids.

Energy production and conversion

The genome of C. indolis contains 261 genes in COG category (C) Energy production and conversion, 28 of which are not found in the near relatives analyzed, including genes for citrate utilization (Table 7) and nitrogen fixation (Table 8).

Table 7. Selection of C. indolis DSM 755 genes related to citrate utilization.

| Locus Tag | Putative Gene Producta | Gene IDa |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_2892 | holo-ACP synthase (CitX) | EC:2.7.7.61 |

| K401DRAFT_2893 | citrate lyase acyl carrier (CitD) | EC:4.1.3.6 |

| K401DRAFT_2894 | citrate lyase beta subunit (CitE) | EC:4.1.3.6 EC:2.8.3.10 |

| K401DRAFT_2895 | citrate lyase alpha subunit (CitF) | EC:4.1.3.6 EC:2.8.3.10 |

| K401DRAFT_2896 | triphosphoribosyl-dephospho-CoA synthase (CitG) | EC:2.7.8.25 |

| K401DRAFT_2897 | citrate (pro3S)-lyase ligase (CitC) | EC:6.2.1.22 |

| K401DRAFT_2898 | response regulator, CheY-like receiver domain, winged helix DNA binding domain | - |

| K401DRAFT_2899 | signal transduction histidine kinase | - |

| K401DRAFT_2900 | citrate transporter, CITMHS family | KO:K03303 TC.LCTP |

Gene products and Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41].

Table 8. Selection of C. indolis DSM 755 genes related to nitrogen fixation.

| Locus Tag | Putative Gene Product | Gene ID |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_0533 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_0534 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_0535 | nitrogenase subunit (ATPase) (nifH) | pfam00142 |

| K401DRAFT_0884 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_0885 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_0886 | nitrogenase subunit (ATPase) (nifH) | pfam00142 |

| K401DRAFT_3349 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3350 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3351 | nitrogenase subunit (ATPase) (nifH) | pfam00142 |

| K401DRAFT_3874 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifD) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3875 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifK) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3876 | nitrogenase Fe protein | pfam00142 |

| K401DRAFT_3878 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifD) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3879 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifK) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3880 | dinitrogenase Fe-Mo cofactor, (nifH) | pfam02579 |

| K401DRAFT_3895 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifD) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_3896 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifK) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_5519 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifB) | pfam04055 |

| K401DRAFT_5520 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein, α and β chains (nifE) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_5521 | nitrogenase Mo-Fe protein (nifK) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_5522 | nitrogenase component 1, alpha chain (nifN-like) | pfam00148 |

| K401DRAFT_5525 | nitrogenase subunit (ATPase) (nifH) | pfam00142 |

Nitrogenase genes have a common gene identifier (EC:1.18.6.1), therefore the pfam numbers are given to distinguish between subunits. Gene product names and pfam numbers assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41].

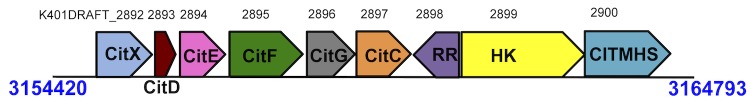

Citrate utilization

Citrate is a metabolic intermediary found in all living cells. In aerobic bacteria, citrate is utilized as part of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In anaerobes, citrate is fermented to acetate, formate, and/or succinate. The first step is the conversion of citrate to acetate and oxaloacetate in a reaction catalyzed by citrate lyase (EC:4.1.3.6) [48]. C. sphenoides, a close relative of C. indolis that does not yet have a sequenced genome has been shown to utilize citrate [49], but there is conflicting evidence as to whether this phenotype is present in C. indolis [28,30]. The genome of C. indolis reveals a group of seven citrate genes organized in a cluster similar to operons found in other bacterial species [48,50] (Figure 3) including CitD, CitE, and CitF, the three subunits of the citrate lyase gene [48], CitG and CitX which have been shown to be necessary for citrate lyase function [50], CitMHS, a citrate transporter, and a putative two component system similar to citrate regulatory mechanisms in other bacteria [51].

Figure 3.

Citrate utilization genes are in a single gene cluster on K401DRAFT_scaffold0000.1.1, including the citrate transporter CitMHS, and a putative two-component system.

Nitrogen Fixation

Nitrogen fixation has been observed in other clostridia [52,53] but has not been demonstrated in the C. saccharolyticum species group. It has been suggested that the capacity to fix nitrogen confers a selective advantage to cellulolytic microbes that live in nitrogen limited environments such as many soils [52]. The functional summary suggests that C. indolis can fix nitrogen. The C. indolis genome reveals 22 nitrogenase related genes in four gene clusters (Table 8), none of which are found in the near relatives analyzed in this study. A minimum set of six genes encoding for structural and biosynthetic components of a functional nitrogenase complex have been hypothesized [54]. Genes needed for the nitrogenase structural component proteins (nifH, nifD, and nifK) are present in C. indolis, but one of the three genes required to synthesize the nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor (nifN) is not identified. Follow up experiments are needed to determine whether C. indolis can fix nitrogen as predicted by the genome analysis.

Lactate utilization

The genome of C. indolis includes both D- and L-lactate dehydrogenases, which convert lactate to pyruvate. Additionally, there is a lactate transporter, suggesting that C. indolis is able to utilize exogenous lactate [Table 9].

Table 9. Selection of C. indolis DSM 755 genes related to lactate utilization.

| Locus Tag | Putative Gene Product | Gene ID |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_1877 | L-lactate dehydrogenase | EC:1.1.1.27 |

| K401DRAFT_5775 | L-lactate dehydrogenase | EC:1.1.1.27 |

| K401DRAFT_3431 | L-lactate transporter, LctP family | TC.LCTP |

| K401DRAFT_3220 | D-lactate dehydrogenase | EC:1.1.1.28 |

Annotations assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41]

Bacterial microcompartments (BMC)

The C. indolis genome contains genes associated with bacterial microcompartment shell proteins. Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) are proteinaceous organelles involved in the metabolism of ethanolamine, 1,2-propanediol, and possibly other metabolites (Rev in [55-57]). BMCs are often encoded by a single operon or contiguous stretch of DNA. The different metabolic types of BMCs can be distinguished by a key enzyme (e.g., ethanolamine lyase and propanediol dehydratase) related to its metabolic function. While the other associated genes in the operon can vary, they frequently include an alcohol dehydrogenase, an aldehyde dehydrogenase, an aldolase and an oxidoreductase.

In C. indolis there are 2 separate genetic loci that code for BMCs (Table 10 and 11 and Figure 4). One C. indolis locus (Table 10) contains a gene (K401DRAFT_2189) with sequence similarity to a B12-independent propanediol dehydratase found in Roseburia inulinivorans and Clostridium phytofermentans [58,59] (both members of the Lachnospiraceae). This enzyme has been shown to be involved in the metabolism of fucose and rhamnose [58,59] and was subsequently categorized as the glycyl radical prosthetic group-based (grp) BMC [60]. The glycyl radical family of enzymes was recently expanded to include a choline trimethylamine lyase activity that is part of a microcompartment loci in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans [61]. The corresponding C. indolis enzymes (K401DRAFT_2189 and K401DRAFT_2190) are more similar to the D. desulfuricans protein, but there are differences in the gene content of the microcompartment loci. Further work is needed to determine the physiological role of this microcompartment.

Table 10. grp-BMC genes found in the C. indolis genome.

| Locus Tag | Product Name | Gene ID/ Protein Information |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_2181 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | COG0789 |

| K401DRAFT_2182 | Predicted membrane protein | COG2510 |

| K401DRAFT_2183 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2184 | Predicted membrane protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2185 | Hypothetical protein | - |

| K401DRAFT_2186 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2187 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2188 | NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase | pfam00171 |

| K401DRAFT_2189 | Pyruvate formate lyase | pfam02901 |

| K401DRAFT_2190 | Pyruvate formate lyase activating enzyme | pfam04055 |

| K401DRAFT_2191 | Ethanolamine utilization protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2192 | Ethanolamine utilization protein | pfam10662 |

| K401DRAFT_2193 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, class IV | pfam00465 |

| K401DRAFT_2194 | Ethanolamine utilization cobalamin adenosyltransferase | COG4892 |

| K401DRAFT_2195 | Ethanolamine utilization protein, possible chaperonin | COG4820 |

| K401DRAFT_2196 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2197 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam03319 |

| K401DRAFT_2198 | Ethanolamine utilization protein | pfam06249 |

| K401DRAFT_2199 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_2200 | NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase | pfam00171 |

| K401DRAFT_2201 | Propanediol utilization protein | pfam06130 |

| K401DRAFT_2202 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

Annotations assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41].

Table 11. CoAT BMC genes found in the C. indolis genome.

| Locus Tag | Product Name | Gene ID/ Protein Information |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_4970 | DeoRC transcriptional regulator | pfam00455 |

| K401DRAFT_4969 | fucA, L-fuculose-phosphate aldolase | EC:4.1.2.17 |

| K401DRAFT_4968 | pduP, propionaldehyde dehydrogenase | pfam00171 |

| K401DRAFT_4967 | eutM, ethanolamine utilization protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_4966 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_4965 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_4964 | Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism/carboxysome shell protein | pfam00936 |

| K401DRAFT_4963 | Pdul, propanediol utilization protein | pfam06130 |

| K401DRAFT_4962 | eutN_CcmL | pfam03319 |

| K401DRAFT_4961 | SBP_bac_8, ABC-type sugar transporter | pfam13416 |

| K401DRAFT_4960 | Uncharacterized NAD(FAD)-dependent dehydrogenase | COG0446 |

| K401DRAFT_4959 | CoA-transferase | pfam01144 |

| K401DRAFT_4958 | CoA-transferase | pfam01144 |

| K401DRAFT_4957 | Fe-ADH, Alcohol dehydrogenase | pfam00465 |

Annotations assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41]

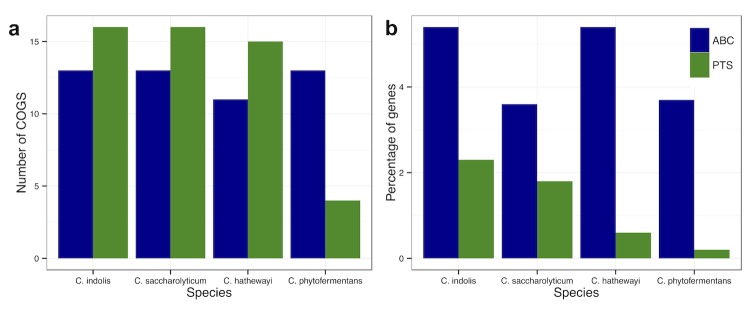

Figure 4.

CoAT BMC operon found in C. indolis, Caldalkalibacillus thermarum, C. stricklandii, C. saccharolyticum, and Bacillus selenitrireducens. Gene details are found in Table 11.

The second C. indolis BMC loci (Table 11 and Figure 4) is even more enigmatic. This loci contains the shell proteins, alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase, aldolase and oxidoreductase commonly found in microcompartments, but it lacks a known key enzyme. Homologs of this operon were found in four other bacterial species (Figure 4). They are all missing a known key enzyme and contain 2 genes annotated as CoA-transferase. We propose that the C. indolis genome and these other bacteria contain a novel type of microcompartment, designated the CoAT BMC. It is not clear that the function of the 2 annotated CoA-transferase genes are as predicted and further research is needed to demonstrate the physiological role of this BMC.

Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism

Protocatechuate and other aromatics are intermediaries in the degradation of lignin in plant rich environments [62]. The genome of C. indolis contains two protocatechuate dioxygenases and an aromatic hydrolase, revealing the potential for utilizing aromatic compounds (Table 12).

Table 12. Selection of C. indolis DSM 755T genes related to degradation of aromatics.

| Locus Tag | Putative Gene Product | Gene ID |

|---|---|---|

| K401DRAFT_3571 | Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase beta subunit | EC:1.13.11.3 |

| K401DRAFT_3568 | Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase beta subunit | EC:1.13.11.3 |

| K401DRAFT_3412 | Aromatic ring hydroxylase | EC:5.3.3.3 EC:4.2.1.120 |

Annotations assigned by the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) database [41]

Conclusion

The genomic sequence of C. indolis reported here reveals the metabolic potential of this organism to utilize a wide assortment of fermentable carbohydrates and intermediates including citrate, lactate, malate, succinate, and aromatics, and points to potential ecological roles in nitrogen fixation and ethanolamine utilization. Further culture-based characterization is necessary to confirm the metabolic activity suggested by this genomic analysis, and to expand the description of C. indolis.

Abbreviations:

- DSM- German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany), ATCC

American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD, USA), RDP: Ribosomal Database Project (East Lansing, MI, USA), JGI: Joint Genomics Institute (Walnut Creek, CA, USA)

References

- 1.Collins MD, Lawson PA, Willems A, Cordoba JJ, Fernandez-Garayzabal J, Garcia P, Cai J, Hippe H, Farrow JA. The phylogeny of the genus Clostridium: proposal of five new genera and eleven new species combinations. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994; 44:812-826 10.1099/00207713-44-4-812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 1987; 4:406-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783-791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:11030-11035 10.1073/pnas.0404206101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray WD, Khan AW. Clostridium saccharolyticum sp. nov., a saccharolytic species from sewage sludge. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1982; 32:132-135 10.1099/00207713-32-1-132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray WD. Symbiotic relationship of Bacteroides cellulosolvens and Clostridium saccharolyticum in cellulose fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 1986; 51:710-714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palop ML, Valles S, Pinaga F, Flors A. Isolation and Characterization of an Anaerobic, Cellulolytic Bacterium, Clostridium celerecrescens sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1989; 39:68-71 10.1099/00207713-39-1-68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mechichi T, Patel BKC, Sayadi S. Anaerobic degradation of methoxylated aromatic compounds by Clostridium methoxybenzovorans and a nitrate-reducing bacterium Thauera sp. strain Cin3,4. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2005; 56:224-230 10.1016/j.ibiod.2005.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heritage AD, MacRae IC. Degradation of lindane by cell-free preparations of Clostridium sphenoides. Appl Environ Microbiol 1977; 34:222-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons NE, Murray RGE. Proposals Concerning the Higher Taxa of Bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1978; 28:1-6 10.1099/00207713-28-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray RGE. The Higher Taxa, or, a Place for Everything...? In: Holt JG (ed), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, First Edition, Volume 1, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1984, p. 31-34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. List no. 132. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:469-472 10.1099/ijs.0.022855-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainey FA. Class II. Clostridia class nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 3, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009, p. 736. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prévot AR. In: Hauderoy P, Ehringer G, Guillot G, Magrou. J., Prévot AR, Rosset D, Urbain A (eds), Dictionnaire des Bactéries Pathogènes, Second Edition, Masson et Cie, Paris, 1953, p. 1-692. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rainey FA. Family V. Lachnospiraceae fam. nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 3, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009, p. 921. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prazmowski A. "Untersuchung über die Entwickelungsgeschichte und Fermentwirking einiger Bakterien-Arten." Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Leipzig, Germany, 1880, p. 366-371. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith LDS, Hobbs G. Genus III. Clostridium Prazmowski 1880, 23. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 551-572. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClung LS, McCoy E. Genus II. Clostridium Prazmowski 1880. In: Breed RS, Murray EGD, Smith NR (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Seventh Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1957, p. 634-693. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClung LS, McCoy E. (1957) Genus II Clostridium Prazmovski 1880. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 634–693. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng H, Vaughn RH. Clostridium rubrum sp. n. and other pectinolytic clostridia from soil. J Bacteriol 1963; 85:1104-1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drasar BS, Goddard P, Heaton S, Peach S, West B. Clostridia isolated from faeces. J Med Microbiol 1976; 9:63-71 10.1099/00222615-9-1-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woo PCY. Clostridium bacteraemia characterised by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. J Clin Pathol 2005; 58:301-307 10.1136/jcp.2004.022830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology: Volume Three: The Firmicutes (2009). 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. Lactate-Utilizing Bacteria, Isolated from Human Feces, That Produce Butyrate as a Major Fermentation Product. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004; 70:5810-5817 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5810-5817.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antranikian G, Friese C, Quentmeier A, Hippe H, Gottschalk G. Distribution of the ability for citrate utilization amongst Clostridia. Arch Microbiol 1984; 138:179-182 10.1007/BF00402115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warnick Thomas A. Clostridium phytofermentans sp. nov., a cellulolytic mesophile from forest soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1155-1160 10.1099/ijs.0.02125-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett S. Solexa, Inc. Pharmacogenomics 2004; 5:433-438 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mingkun L, Copeland A, Han J. (2011) DUK. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: JGI. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gnerre S, Maccallum I, Przybylski D, Ribeiro FJ, Burton JN, Walker BJ, Sharpe T, Hall G, Shea TP, Sykes S, et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 108:1513-1518 10.1073/pnas.1017351108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowe TM, Eddy SR (1997) tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 0955–0964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:7188-7196 10.1093/nar/gkm864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:1335-1337 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markowitz VM, Chen IM, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, Ratner A, Jacob B, Huang J, Williams P, et al. IMG: the integrated microbial genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 40:D115-D122 10.1093/nar/gkr1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantarel BL1 Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:D233-D238 10.1093/nar/gkn663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jojima T, Omumasaba CA, Inui M, Yukawa H. Sugar transporters in efficient utilization of mixed sugar substrates: current knowledge and outlook. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2009; 85:471-480 10.1007/s00253-009-2292-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stülke J, Hillen W. Regulation of carbon catabolism in Bacillus species. Annu Rev Microbiol 2000; 54:849-880 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saier MH. Families of transmembrane sugar transport proteins. Mol Microbiol 2000; 35:699-710 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brückner R, Titgemeyer F. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: choice of the carbon source and autoregulatory limitation of sugar utilization. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2002; 209:141-148 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)00559-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forward JA, Behrendt MC, Wyborn NR, Cross R, Kelly DJ. TRAP transporters: a new family of periplasmic solute transport systems encoded by the dctPQM genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and by homologs in diverse gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 1997; 179:5482-5493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bott M. Anaerobic citrate metabolism and its regulation in enterobacteria. Arch Microbiol 1997; 167:78-88 10.1007/s002030050419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walther R, Hippe H, Gottschalk G. Citrate, a specific substrate for the isolation of Clostridium sphenoides. Appl Environ Microbiol 1977; 33:955-962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider K, Dimroth P, Bott M. Biosynthesis of the Prosthetic Group of Citrate Lyase †. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000; 39:9438-9450 10.1021/bi000401r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brocker M, Schaffer S, Mack C, Bott M. Citrate Utilization by Corynebacterium glutamicum Is Controlled by the CitAB Two-Component System through Positive Regulation of the Citrate Transport Genes citH and tctCBA. J Bacteriol 2009; 191:3869-3880 10.1128/JB.00113-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leschine SB, Holwell K, Canale-Parola E. Nitrogen fixation by anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria. Science 1988; 242:1157-1159 10.1126/science.242.4882.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen JS, Toth J, Kasap M. Nitrogen-fixation genes and nitrogenase activity in Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium beijerinckii. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2001; 27:281-286 10.1038/sj.jim.7000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dos Santos PC, Fang Z, Mason SW, Setubal JC, Dixon R. Distribution of nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase-like sequences amongst microbial genomes. BMC Genomics 2012; 13:162 10.1186/1471-2164-13-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeates TO, Thompson MC, Bobik TA. The protein shells of bacterial microcompartment organelles. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2011; 21:223-231 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. Bacterial Microcompartments. Annu Rev Microbiol 2010; 64:391-408 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garsin DA. Ethanolamine utilization in bacterial pathogens: roles and regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010; 8:290-295 10.1038/nrmicro2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petit E, LaTouf WG, Coppi MV, Warnick TA, Currie D, Romashko I, Deshpande S, Haas K, Alvelo-Maurosa JG, Wardman C, et al. Involvement of a Bacterial Microcompartment in the Metabolism of Fucose and Rhamnose by Clostridium phytofermentans. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e54337 10.1371/journal.pone.0054337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scott KP, Martin JC, Campbell G, Mayer CD, Flint HJ. Whole-Genome Transcription Profiling Reveals Genes Up-Regulated by Growth on Fucose in the Human Gut Bacterium “Roseburia inulinivorans.”. J Bacteriol 2006; 188:4340-4349 10.1128/JB.00137-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jorda J, Lopez D, Wheatley NM, Yeates TO. Using comparative genomics to uncover new kinds of protein-based metabolic organelles in bacteria. Protein Sci 2013; 22:179-195 10.1002/pro.2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:21307-21312 10.1073/pnas.1215689109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crawford RL, McCoy E, Harkin JM, Kirk TK, Obst JR. Degradation of methoxylated benzoic acids by a Nocardia from a lignin-rich environment: significance to lignin degradation and effect of chloro substituents. Appl Microbiol 1973; 26:176-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA. (1997) Phylogenic relationships. In: Rood JI, McClane BA, Songer JG, Titball RW, editors. The Clostridia: Molecular Biology and Pathogenesis. New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawson PA, Llop-Perez P, Hutson RA, Hippe H, Collins MD. Towards a phylogeny of the clostridia based on 16S rRNA sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1993; 113:87-92 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]