The changes in the numbers, phenotypes, and subpopulations of B lymphocytes in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) with different response levels after mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment were investigated. The findings imply that MSCs might exert therapeutic effects in cGVHD patients, accompanied by alterations of naïve and memory B-cell subsets, modulating the plasma B cell-activating factor (BAFF) levels and BAFF receptor expression on B lymphocytes.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stromal cells, Chronic graft-versus-host disease, B cell-activating factor, B-cell homeostasis

Abstract

Although mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) possess immunomodulatory properties and exhibit promising efficacy against chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), little is known about the immune changes by which MSCs ameliorate cGVHD in vivo. Recent studies have suggested that B lymphocytes might play an important role in the pathogenesis of cGVHD. In this study, we investigated changes in the numbers, phenotypes, and subpopulations of B lymphocytes in cGVHD patients who showed a complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or no response (NR) after MSC treatment. We found that the frequencies and numbers of CD27+ memory and pre-germinal center B lymphocytes were significantly increased in the CR and PR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment but decreased in the NR patients. A further analysis of CR/PR cGVHD patients showed that MSC treatment led to a decrease in the plasma levels of B cell-activating factor (BAFF) and increased expression of the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) on peripheral B lymphocytes but no changes in plasma BAFF levels or BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes in NR patients. Overall, our findings imply that MSCs might exert therapeutic effects in cGVHD patients, accompanied by alteration of naïve and memory B-cell subsets, modulating plasma BAFF levels and BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes.

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and limits the wider use of this transplantation strategy. With improvements in immunosuppressive therapy and supportive care, fewer patients have developed acute GVHD (aGVHD) in recent years. However, the incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) has not improved and has become one of the most common and clinically significant problems affecting long-term HSCT survivors [1, 2]. cGVHD has distinct manifestations from those of aGVHD and has been considered an autoimmune disorder [3, 4]. The medicines used to treat cGVHD remain unsatisfactory, especially for refractory cGVHD [5]. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent stem cells that play an important role in tissue regeneration [6]. Moreover, MSCs also possess immunosuppressive properties through the modulation of T cells, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, B cells, and so on. The immunomodulatory properties of MSCs have attracted extensive attention for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, solid organ transplantation, and so forth [7–9]. Although the efficacy of MSCs against steroid-resistant aGVHD is a matter of controversy [10–12], several ongoing clinical studies on cGVHD appear promising [13, 14].

Given that cGVHD resembles an autoimmune disorder, although donor-derived T lymphocytes have classically been considered the main effector cell, recent evidence has indicated that B lymphocytes are involved in the pathogenesis of cGVHD [15–17]. After allogeneic HSCT, donor-derived B lymphocytes reconstitute in the recipients. However, B-lymphocyte homeostasis can be altered during B-lymphocyte reconstitution, and this could impair peripheral B-lymphocyte tolerance, leading to the production of autoantibodies in cGVHD [18, 19]. B cell-activating factor (BAFF) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily and is well known for its essential role in the survival and maturation of B cells via binding to the receptors BCMA (B-cell maturation protein), TACI (transmembrane activator and CAML interactor), and BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) [20]. B-lymphocyte homeostasis depends on the signaling of the B-cell receptor and BAFF [21, 22]; elevated BAFF levels contribute to B-cell activation through the BAFF-R on B cells in patients with cGVHD [23]. Given the clinical application of rituximab, which targets and destroys CD20-expressing B lymphocytes, B-lymphocyte depletion may be an effective treatment of cGVHD, especially in refractory cases [24–26]. Recent studies have suggested that altered B-lymphocyte homeostasis after allogeneic HSCT may affect the development of cGVHD and the response to rituximab therapy in cGVHD patients [27, 28].

In the present study, we investigated alterations in the naïve and memory B-cell subsets in cGVHD patients after treatment with MSCs.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

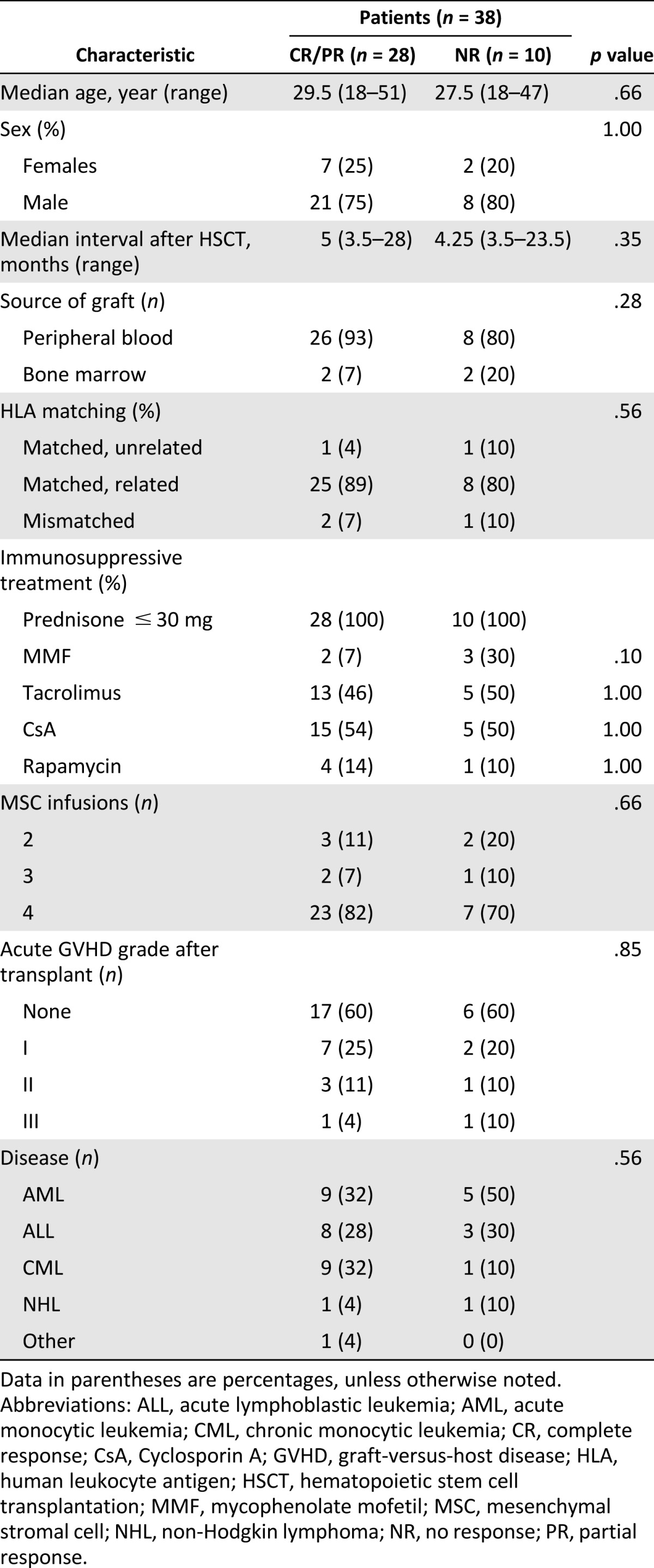

A total of 38 cGVHD patients were enrolled in this study. cGVHD was defined by the presence of at least one diagnostic or distinctive manifestation of cGVHD that had been confirmed by pertinent biopsy. All enrolled patients showed extensive cGVHD involving two or more organs, and their manifestations of cGVHD showed no improvement or progression after at least 2 months of treatment with standard immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, alone or combined with other immunosuppressants. In addition to the original immunosuppressive therapy, all candidates received at least two infusions of MSCs (1 × 106 cells per kilogram) at 4-week intervals derived from healthy unrelated donors. The clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Follow-up examinations were conducted every 3 months until 12 months after the first MSC infusion.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of chronic graft-versus-host disease patients

The NIH consensus criteria for cGVHD diagnosis, organ scoring, and global assessment of cGVHD status were used in the present study [29]. At least two physicians independently assessed the cGVHD patients at each follow-up visit. The response to MSC treatment was defined as follows: CR, resolution of all clinical manifestations and laboratory data of the involved organs; PR, improvement by at least one point in the involved organ or more than 25% improvement of clinical laboratory data of the involved organs without CR; NR, deterioration, no improvement, or less than 25% improvement of clinical manifestations and laboratory data.

This study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the modified Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the relevant ethics review board before we began. All recipients and donors provided written informed consent.

Processing of Peripheral Blood Cells and Plasma

Heparinized peripheral blood was obtained from patients with cGVHD before MSC treatment and at 3, 6, and 12 months after the first infusion of MSCs. Plasma was separated from whole blood cells by centrifugation at 600g, stored in aliquots at −80°C, and used after the first thaw for assessment of the cytokine levels. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden, http://www.gelifesciences.com) and stored in aliquots in liquid nitrogen.

MSC Preparation and Administration

Under good manufacturing practice conditions, MSCs were generated from the bone marrow of unrelated donors as described previously [14, 30, 31]. MSCs expressed CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166 but not CD34 and CD45 (supplemental online Fig. 1). They differentiated into osteoblasts and adipocytes under special culture conditions (supplemental online Fig. 1). Release testing for MSCs included viability, purity, sterility, endotoxin, and Mycoplasma-free. MSCs at passage 4 or 5 were administered to the patients by intravenous infusion at a dose of 1 × 106 cells per kilogram of bodyweight. Detailed information for MSC preparation is presented in the supplemental online data.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cell surface staining was performed as described previously [32, 33], and PBMCs were stained with antibodies against BAFF-R-phycoerythrin (PE), IgD-peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex (PerCP), CD1d-PE, CD11b-PE, CD19-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD19-Horizon V500, CD23-PerCP-cyanine dye (Cy)5.5, CD24-PE, CD25-PE-Cy7, CD25-allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7, CD27-FITC, CD27-APC, CD38-PE-Cy7, CD38-PE, CD80-PE-Cy7, CD86-APC, CD127-PerCP-Cy5.5, and BAFF-R-PE (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com). The lymphocyte gate was established using forward and side scatter parameters. The positive gate was set using isotype controls (all from BD Biosciences Pharmingen). The cell phenotypes and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of BAFF-R were evaluated using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson and Company, San Jose, CA, http://www.bd.com) or a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, http://www.beckmancoulter.com). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, version 7.6 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, http://www.treestar.com).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Plasma-soluble BAFF levels in cGVHD patients before and after MSC treatment were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system, according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, http://www.rndsystems.com).

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained before and after treatment of cGVHD patients with MSCs were compared using the Wilcoxon t test (signed-rank test), and the data from the CR and PR cGVHD patients and NR cGVHD patients were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 14.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/). All statistical tests were considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Results

Increases in Memory B Lymphocytes in CR and PR cGVHD Patients After Treatment With MSCs

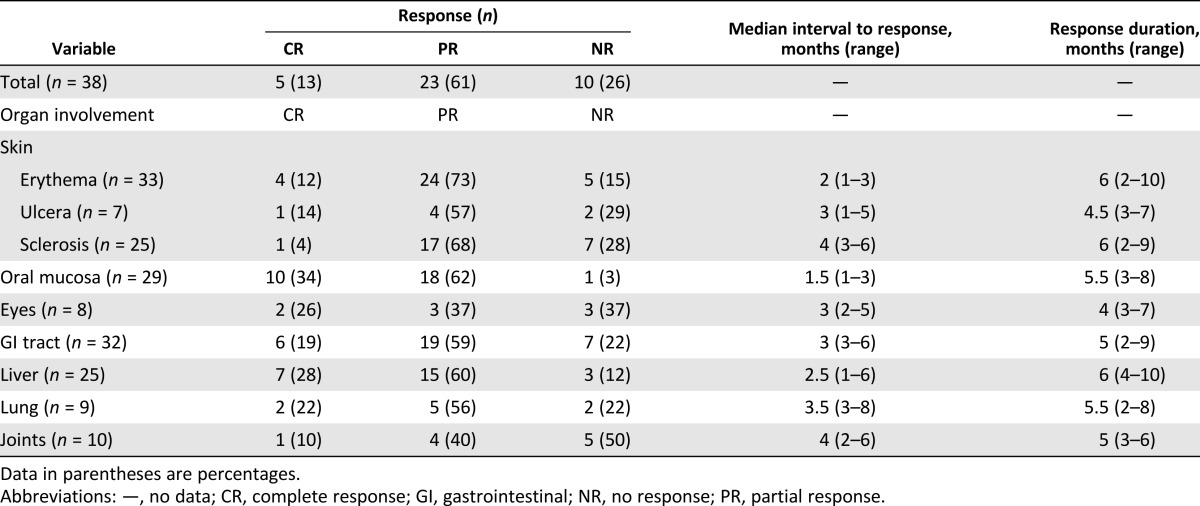

In this prospective study, the enrolled 38 cGVHD patients after MSC treatment were studied during 12 months of follow-up. As shown in Table 1, the patient characteristics before MSC treatment were not significantly different between the 2 groups. In the calculation of the maximum response for the 12-month follow-up period, 5 patients had a CR, 23 patients had a PR, and 10 patients had a NR (Table 2). The best therapeutic effects of the CR and PR patients were observed 3 to 6 months after the first MSC infusion (Table 2); thus, we analyzed the changes to the peripheral B cells and plasma BAFF levels in enrolled patient at 3 and 6 months after the first MSC infusion as the post-treatment point. Analysis of lymphocytes status requires leukapheresis samples, which we obtained from 11 CR and PR patients and 6 NR patients, all of whom had received 4 doses of MSCs and consented to the collection of samples. The characteristics of the 17 representative cGVHD patients (11 CR and PR patients and 6 NR patients) are shown in supplemental online Table 1.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical results in 12 months of follow-up after first mesenchymal stromal cell infusion

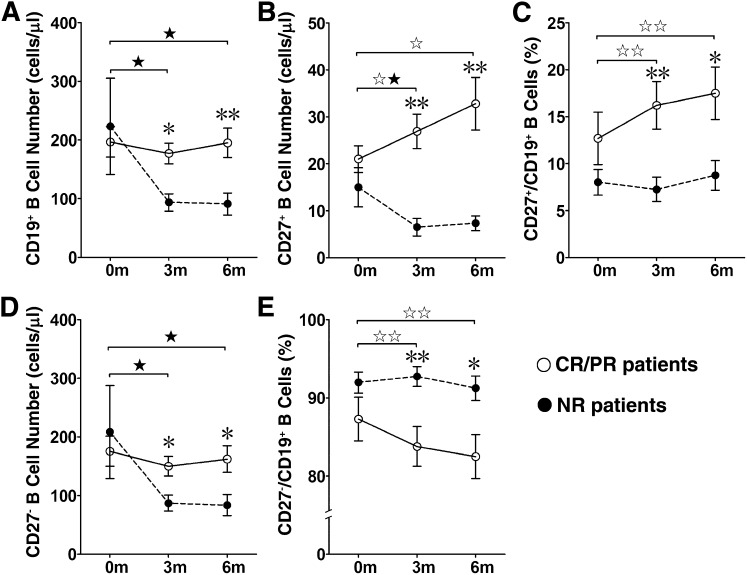

We observed that the B-lymphocyte numbers in the CR and PR cGVHD patients were not affected by treatment with MSCs but were markedly decreased in the NR cGVHD patients (93.7 ± 14.8 cells per microliter at 3 months and 91.2 ± 18.9 cells per microliter at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment numbers (223.3 ± 82.1 cells per microliter, p < .05). After MSC treatment, the B lymphocyte numbers in the NR cGVHD patients were significantly lower than those in the CR and PR cGVHD patients (177.0 ± 17.6 cells per microliter at 3 months, p < .01, and 195.1 ± 25.0 cells per microliter at 6 months, p < .01, Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

There were more memory B lymphocytes in complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) patients than in no response (NR) cGVHD patients after mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment. The numbers and frequencies of CD19+ B cells, CD27+ memory B cells, and CD27− B cells in cGVHD patients (n = 17) were measured before and 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment. At 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment, the number of CD19+ B lymphocytes in the NR cGVHD patients (n = 6) was significantly decreased, the number of CD19+ B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients (n = 11) was higher than that in the NR cGVHD patients (A). The number (B) and frequency (C) of CD27+ memory B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients were significantly increased at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment and were significantly higher than those in the NR cGVHD patients. The number of CD27− naïve B lymphocytes in the NR cGVHD patients was significantly decreased at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment and significantly lower than that in the CR and PR cGVHD patients (D). The frequency (E) of CD27− naïve B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients was decreased at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment and significantly lower than that in the NR cGVHD patients. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in the CR and PR cGVHD patients, ☆, p < .05, ☆☆, p < .01; before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in NR cGVHD patients, ★, p < .05, ★★, p < .01; and CR and PR cGVHD patients vs. NR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment, ∗, p < .05, ∗∗, p < .01).

Next, we analyzed CD27+ memory B lymphocytes and CD27− naïve B lymphocytes. The results showed that the CD27+ memory B lymphocyte numbers in the CR and PR cGVHD patients were significantly increased after MSC treatment (26.9 ± 3.6 cells per microliter at 3 months and 32.8 ± 5.6 cells per microliter at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment values (21.0 ± 2.9 cells per microliter, p < .05; Fig. 1B). The frequency of CD27+ B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients was also markedly increased after MSC treatment (16.2% ± 2.5% at 3 months and 17.5% ± 2.8% at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment values (12.7% ± 2.8%, p < .01; Fig. 1C). Although the CD27+ memory B lymphocyte numbers were decreased at 3 months after MSC treatment, neither the number nor the frequency of CD27+ memory B lymphocytes in the NR cGVHD patients was significantly affected by treatment with MSCs (Fig. 1B, 1C). After MSC treatment, the CD27+ memory B lymphocyte numbers were significantly higher in the CR and PR cGVHD patients than in the NR cGVHD patients (6.5 ± 1.9 cells per microliter at 3 months and 7.3 ± 1.6 cells per microliter at 6 months, p < .01; Fig. 1B). The frequency of CD27+ memory B lymphocytes was also higher in the CR and PR cGVHD patients (16.2% ± 2.5% at 3 months and 17.5% ± 2.8% at 6 months) than in the NR cGVHD patients (7.3% ± 1.3% at 3 months, p < .05, and 8.8% ± 1.6% at 6 months, p < .05; Fig. 1C).

CD27− naïve B lymphocyte numbers in the post-treatment samples from NR patients (87.2 ± 13.6 cells per microliter at 3 months and 83.8 ± 18.0 cells per microliter at 6 months) were decreased compared with the pretreatment samples (208.3 ± 79.2 cells per microliter, p < .05; Fig. 1D). Although the CD27− B lymphocyte numbers did not change after MSC treatment in the CR or PR cGVHD patients (Fig. 1D), their frequency was consistently, but only marginally, decreased in these patients after treatment (Fig. 1E).

After MSC treatment, both CD27+ memory B lymphocyte numbers and CD27− naïve B lymphocyte numbers were significantly lower in the NR cGVHD patients than in the post-treatment CR and PR cGVHD patients (Fig. 1B, 1D). Collectively, these findings suggest that MSC treatment affects the levels of CD27+ B lymphocytes in CR and PR cGVHD patients.

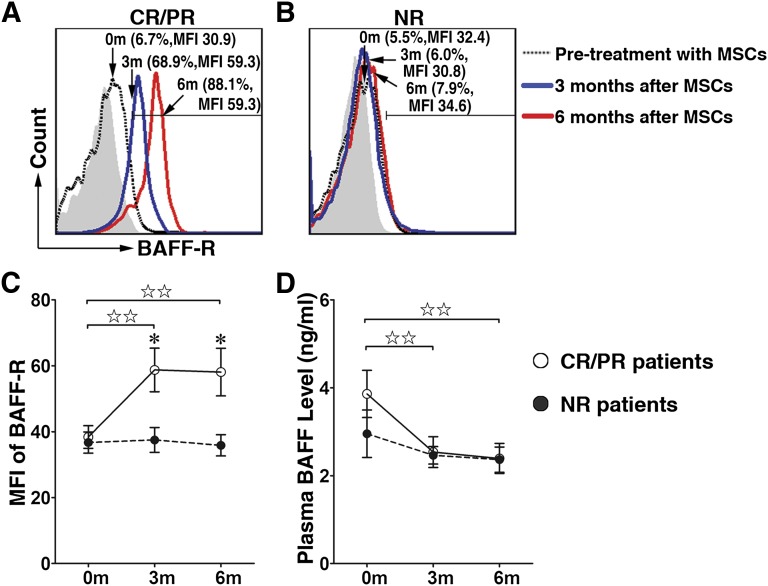

Lower Plasma BAFF Levels and Higher BAFF-R Expression on Peripheral B Lymphocytes in CR and PR cGVHD Patients After MSC Treatment

Previous studies have indicated that plasma BAFF concentrations and BAFF-R expression levels on B lymphocytes are significantly associated with cGVHD [34]. Thus, we measured the plasma BAFF levels and BAFF-R expression on CD19+ B lymphocytes in cGVHD patients before and after MSC treatment. We found that BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes was lower in the CR and PR patients before treatment (MFI score 38.4 ± 3.4) than in the MSC-treated patients (MFI score 58.7 ± 6.6 at 3 months and 58.1 ± 7.2 at 6 months, p < .01; Fig. 2A) but was unchanged by MSC treatment in the NR patients (Fig. 2B). As a result, the BAFF-R expression levels on B lymphocytes in the pretreatment samples from NR patients (MFI score 36.7 ± 3.2) were similar to those in the pretreatment samples from the CR and PR patients (MFI score 38.4 ± 3.4). Also, BAFF-R expression in the NR patients after treatment (MFI score 37.5 ± 3.8 at 3 months and 35.9 ± 3.2 at 6 months) was significantly lower than that in the MSC-treated CR and PR patients (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Decreased BAFF levels and increased BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes in CR and PR chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) patients after MSC treatment. BAFF-R expression levels on B lymphocytes before (dashed line) and 3 months (blue line) and 6 months (red line) after MSC treatment are shown for representative samples of 11 CR and PR cGVHD patients (A) and 6 NR cGVHD patients (B). Filled histograms indicate isotype controls. Bars indicate mean fluorescence intensity score of BAFF-R expressed on B lymphocytes in cGVHD patients (C). Plasma BAFF levels at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment decreased in CR and PR cGVHD patients but did not change in NR patients (D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in CR and PR cGVHD patients, ☆, p < .05, ☆☆, p < .01; before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in NR cGVHD patients, ★, p < .05, ★★, p < .01; and CR and PR cGVHD patients vs. NR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment, ∗, p < .05, ∗∗, p < .01). Abbreviations: BAFF, B cell-activated factor; BAFF-R, B cell-activated factor receptor; CR, complete response; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cell; NR, no response; PR, partial response.

The plasma BAFF concentrations in the MSC-treated CR and PR cGVHD patients (2.5 ± 0.4 ng/ml at 3 months and 2.4 ± 0.3 ng/ml at 6 months) were decreased compared with those in the CR and PR patients before treatment (3.86 ± 0.54 ng/ml, p < .01; Fig. 2D); however, the BAFF levels in the NR cGVHD patients did not obviously change after MSC treatment (Fig. 2D).

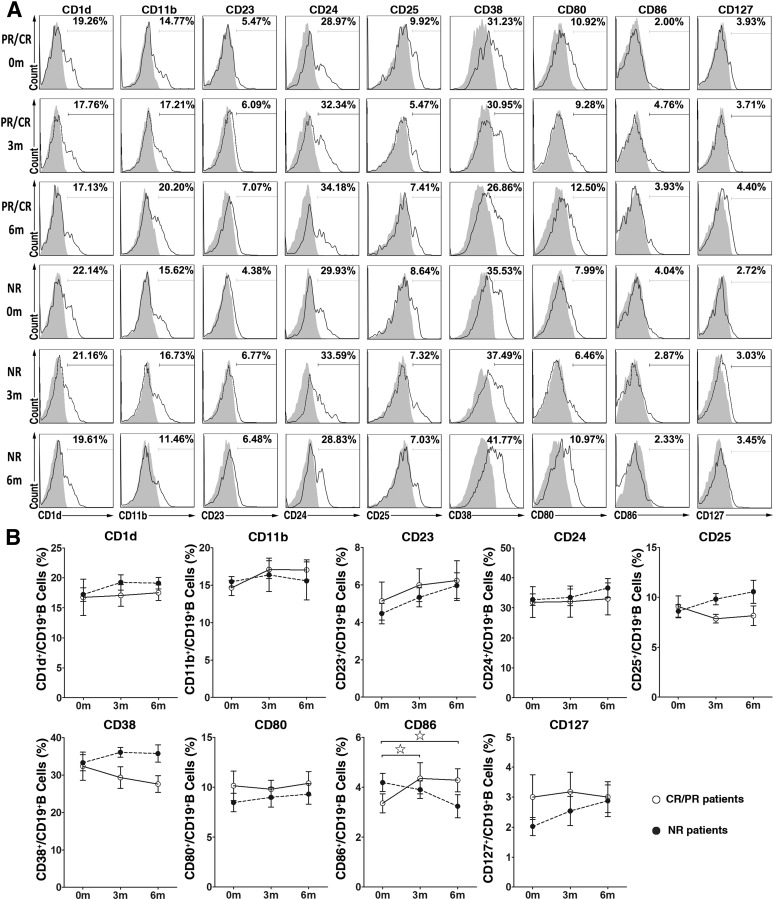

Changes in Peripheral B Lymphocyte Phenotypes in cGVHD Patients After MSC Treatment

We further analyzed the differences in B-lymphocyte phenotypes in pre- and post-treatment cGVHD patients by measuring the expression levels of a panel of B-lymphocyte surface markers, including CD1d, CD11b, CD23, CD24, CD25, CD38, CD80, CD86, and CD127, by flow cytometry. No differences were apparent in the expression of B-lymphocyte surface molecules, including CD1d, CD11b, CD23, CD24, CD25, CD38, CD80, and CD127, before and after MSC treatment in both CR and PR and NR cGVHD patients (Fig. 3). The expression of CD86 on B lymphocytes increased slightly at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment in the CR and PR cGVHD patients but did not change in the NR cGVHD patients (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in B lymphocyte phenotypes in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) patients after mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment. (A): Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface phenotypes (unfilled histograms; filled histograms indicate isotype controls) of peripheral B lymphocytes from representative CR and PR (n = 11) and NR cGVHD patients (n = 6) before and 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment. (B): Open and filled dots indicate the percentage of cells expressing surface markers on B lymphocytes from CR and PR cGVHD patients and NR cGVHD patients (before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in CR and PR cGVHD patients, ☆, p < .05, ☆☆, p < .01; before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in NR cGVHD patients, ★, p < .05, ★★, p < .01; and CR and PR cGVHD patients vs. NR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment, ∗, p < .05, ∗∗, p < .01). Abbreviations: CR, complete response; NR, no response; PR, partial response.

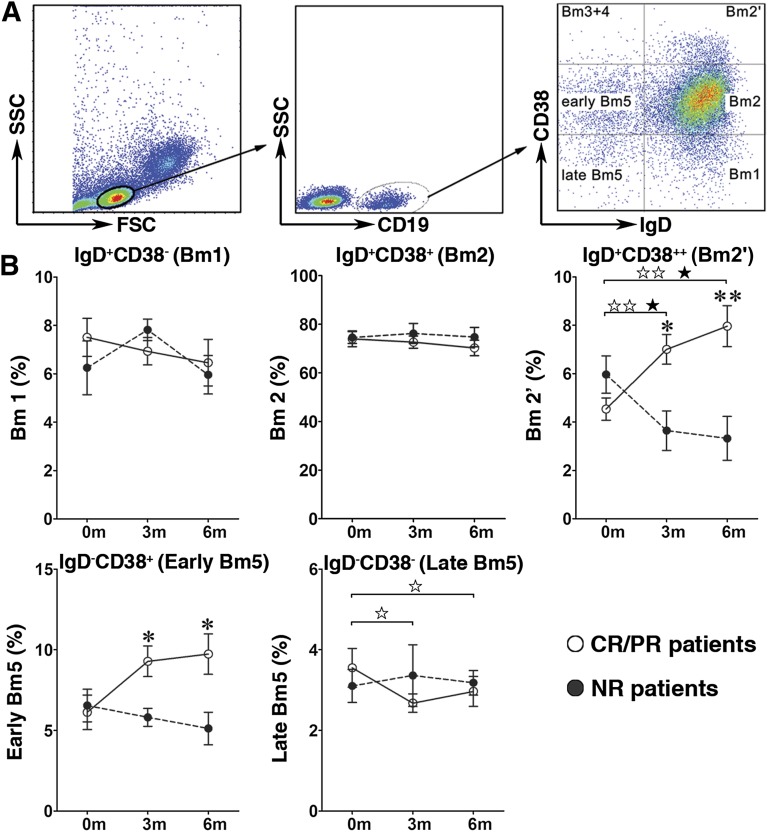

Increases in Pre-Germinal Center and Early Memory B Lymphocytes in CR and PR cGVHD Patients After MSC Treatment

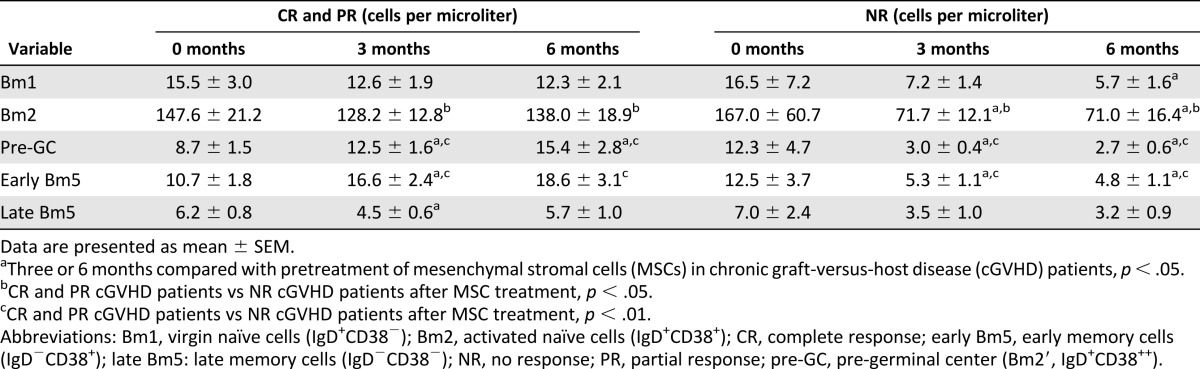

A flow cytometric analysis of the expression of surface markers, including CD19, IgD, CD38, and CD27, is commonly used to analyze human B-lymphocyte populations. IgD/CD38 staining is the basis of the Bm1–Bm5 classification system and can be used to identify multiple B-lymphocyte subsets in human peripheral blood. These subsets include virgin naïve cells (Bm1: IgD+CD38−), activated naïve cells (Bm2: IgD+CD38+), pre-germinal center (pre-GC) cells (Bm2′; IgD+CD38++), GC cells (Bm3-centroblasts and Bm4-centrocytes; both IgD−CD38++), and memory cells (Bm5: IgD−CD38+/−) [35].

In the present study, the Bm1–Bm5 classification system was used to identify the developmental stages of B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of pre- and post-treatment GVHD patients (Fig. 4A). After MSC treatment, the frequency of pre-GC B lymphocytes was markedly increased in the post-treatment CR and PR cGVHD patients (7.0% ± 0.6% at 3 months and 8.0% ± 0.9% at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment patients (4.5% ± 0.5%, p < .01; Fig. 4B). In contrast, the frequency of pre-GC B lymphocytes was decreased by MSC treatment in the NR group of cGVHD patients (3.6% ± 0.8% at 3 months and 3.3% ± 0.9% at 6 months vs. 6.0% ± 0.8% before MSC treatment, p < .05; Fig. 4B). As a result, the frequency of pre-GC B lymphocytes in post-treatment NR cGVHD patients was significantly lower than that in post-treatment CR and PR patients (Fig. 4B). At the same time, the pre-GC B-lymphocyte numbers in CR and PR cGVHD patients were markedly increased after MSC treatment (12.5 ± 1.6 cells per microliter at 3 months and 15.4 ± 2.8 cells per microliter at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment values (8.7 ± 1.5 cells per microliter, p < .05, Table 3) but were significantly decreased in the MSC-treated NR cGVHD patients (3.0 ± 0.4 cells per microliter at 3 months and 2.7 ± 0.6 cells per microliter at 6 months vs. 12.3 ± 4.7 cells per microliter before MSC treatment, p < .05, Table 3). As a result, the pre-GC B-lymphocyte numbers in the MSC-treated NR cGVHD patients were significantly decreased compared with those in the MSC-treated CR and PR patients.

Figure 4.

Increased percentage of pre-germinal center (pre-GC) B lymphocytes in CR and PR chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) patients after mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment. Gated CD19+ B cells from CR and PR (n = 11) and NR (n = 6) cGVHD patients were analyzed based on IgD and CD38 expression using the Bm1–Bm5 classification system (A). After MSC treatment, the frequency of pre-GC B lymphocytes (Bm2′) were significantly increased at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment in the CR and PR cGVHD patients but were significantly decreased in the NR cGVHD patients. The frequency of early memory B lymphocytes (early Bm5) was significantly higher at 3 and 6 months after MSC treatment in the CR and PR cGVHD than that in the NR cGVHD patients (B). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in CR and PR cGVHD patients, ☆, p < .05, ☆☆, p < .01; before vs. 3 or 6 months after MSC treatment in NR cGVHD patients, ★, p < .05, ★★, p < .01; and CR and PR cGVHD patients vs. NR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment, ∗, p < .05, ∗∗, p < .01). Abbreviations: Bm1, virgin naïve cells (IgD+CD38−); Bm2, activated naïve cells (IgD+CD38+); Bm2′, pre-germinal center (IgD+CD38++); CR, complete response; early Bm5, early memory cells (IgD−CD38+); FSC, forward scatter; late Bm5: late memory cells (IgD−CD38−); NR, no response; PR, partial response; SSC, side scatter.

Table 3.

Bm1–Bm5 B-cell numbers in pretreatment and post-treatment chronic graft-versus-host disease patients

After MSC treatment, the frequency of early memory B lymphocytes in post-treatment CR and PR cGVHD patients (9.3% ± 0.9% at 3 months and 9.7% ± 1.3% at 6 months) was markedly higher than that in the post-treatment NR patients (5.8% ± 0.6% at 3 months and 5.1% ± 1.0% at 6 months, p < .05; Fig. 4B). The number of early memory B lymphocytes after MSC treatment in CR and PR cGVHD patients (16.6 ± 2.4 cells per microliter at 3 months) showed a trend toward higher than that before MSC treatment (10.7 ± 1.8 cells per microliter, p < .05, Table 3) but was significantly decreased in the post-treatment NR patients (5.3 ± 1.1 cells per microliter at 3 months and 4.8 ± 1.1 cells per microliter at 6 months) compared with the pretreatment patients (12.5 ± 3.7 cells per microliter, p < .05, Table 3). Therefore, substantially fewer early memory B lymphocytes were present in the post-treatment NR patients than in both post-treatment CR and PR patients.

The frequency of later memory B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients was lower after MSC treatment (2.7% ± 0.2% at 3 months and 3.0% ± 0.4% at 6 months) than before MSC treatment (3.6% ± 0.5%, p < .05, Fig. 4B), but no obvious effect was seen for MSC treatment on the frequency of this B-lymphocyte population in NR cGVHD patients (Fig. 4B). After MSC treatment, the number of late memory B lymphocytes was not significantly changed in the CR and PR or NR cGVHD patients compared with the pretreatment values (Table 3).

Higher Frequency of Unswitched Memory B Lymphocytes in cGVHD Patients

The IgD/CD27 classification system can be used to divide B lymphocytes into naïve B lymphocytes (CD27−IgD+), memory B lymphocytes in which no isotype switching has occurred (CD27+IgD+), and isotype-switched memory B lymphocytes (CD27+IgD−) [35, 36]. Applying the IgD/CD27 classification to analyze B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of pre- and post-treatment cGVHD patients, we found no significant difference in the frequency of these B-lymphocyte subsets after MSC treatment in the CR and PR or NR patients compared with the pretreatment frequencies (supplemental online Fig. 2). After MSC treatment, the number of cells in most of these four B-lymphocyte subsets was unaltered in the CR and PR cGVHD patients. In contrast, the number of naïve B lymphocytes was decreased after MSC treatment in the NR patients (71.8 ± 12.0 cells per microliter at 3 months and 70.7 ± 18.1 cells per microliter at 6 months vs. 185.7 ± 66.8 cells per microliter before MSC treatment, p < .05; supplemental online Table 2). As a result were substantially fewer naïve B lymphocytes were present in the post-treatment NR cGVHD patients (71.8 ± 12.0 cells per microliter at 3 months and 70.7 ± 18.1 cells per microliter at 6 months) than in the post-treatment CR and PR patients (142.7 ± 13.2 cells per microliter at 3 months and 158.1 ± 20.5 cells per microliter at 6 months, p < .01; supplemental online Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, we treated 38 cGVHD patients with MSCs and found 5 patients had a CR, 23 patients had a PR, and 10 patients had a NR. Further analysis found the frequencies and numbers of CD27+ memory and pre-GC B lymphocytes were significantly increased in the CR and PR cGVHD patients after MSC treatment. In addition, the CR and PR cGVHD patients showed a decrease in the plasma levels of BAFF and increased expression of BAFF-R on the peripheral B lymphocytes.

The role of B cells in the pathogenesis of cGVHD has attracted much more attention, because the clinical manifestations of cGVHD are similar to those of autoimmune disorders [15, 18, 37]. Recent studies have proposed that B-cell reconstitution after allogeneic HSCT is involved in the development of chronic GVHD [38]. After allogeneic HSCT, B-cell homeostasis can be altered during B-cell reconstitution, and this could impair the immune tolerance of peripheral B cells.

Patients who develop cGVHD show a faster initial reconstitution of the B-lymphocyte population [39], with an elevated number of transitional CD21− B lymphocytes and a deficiency of memory CD27+ B lymphocytes [40]. We observed that MSC treatment significantly increased the frequency and number of CD27+ memory B lymphocytes in the CR and PR patients at 3 and 6 months, but not in NR patients, suggesting that MSC treatment probably affected the naïve and memory B-cell subsets in the cGVHD patients. CD27 is used as a universal marker of human memory B cells, and its expression can distinguish memory cells (CD27+) from naïve B lymphocytes (CD27−). Recent studies have shown that an enhanced CD27+ B-lymphocyte population is important for long-term allograft acceptance after renal transplantation [41, 42]. In the present study, we found that, before treatment, the cGVHD patients had fewer CD27+ memory B lymphocytes, and, importantly, MSC treatment significantly increased the CD27+ memory B lymphocyte numbers in the CR and PR patients at 3 and 6 months but not in the NR patients.

High levels of BAFF are also correlated with cGVHD development and severity [34]. Inadequate reconstitution of B cells and the persistence of high levels of BAFF have been found in patients with chronic GVHD [43], and these changes might be associated with the expansion of activated CD27+ B cells that produce autoantibody in cGVHD. Any modifications of these are likely to result in moderation of cGVHD manifestation in patients. We also observed that MSC treatment could decrease BAFF levels and significantly increase BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes in the CR and PR cGVHD patients, although not in the NR cGVHD patients. These results indicate that the efficacy of MSC treatment in cGVHD patients might be associated with a decrease in plasma BAFF levels and increased expression of BAFF-R on peripheral B lymphocytes.

Conclusion

Despite the limitation of there being no placebo control group in this study, our results imply that MSC treatment might exert therapeutic effects in cGVHD patients, accompanied by altering the frequency and number of memory B lymphocytes and by regulating the plasma BAFF levels and BAFF-R expression. Future studies to understand the underlying mechanism would also enable us to elucidate the MSCs’ in vivo effects and help to facilitate the design of future clinical studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sum Chee Peng and Xianchang Li for their comments on our article. This study was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Grants 2012CBA01302, 2010CB945400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31171398, 81270646), the National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant S2013030013305), the Key Scientific and Technological Projects of Guangdong Province (Grant 2007A032100003), Key Scientific and Technological Program of Guangzhou City (Grants 2010U1-E00551, 201300000089, and 201400000003-3), and the Fund for Guangdong translational medicine public platform.

Author Contributions

Y.P.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; X.C.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; Qifa Liu: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, provision of study material or patients; D.X., H.Z., Qiuli Liu, M.L., Z.F., X.L., and R.Z.: collection and/or assembly of data; L.L. and J.S.: provision of study material or patients; A.P.X.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: Report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110:3784–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:7–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flowers ME, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood. 2011;117:3214–3219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:443–458. doi: 10.1038/nri3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawitschka A, Ball L, Peters C. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease in children and adolescents. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(suppl):S74–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110:3499–3506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.English K, French A, Wood KJ. Mesenchymal stromal cells: facilitators of successful transplantation? Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uccelli A, Prockop DJ. Why should mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) cure autoimmune diseases? Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Developmental Committee of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: A phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolar J, Villeneuve P, Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells for graft-versus-host disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:257–262. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin PJ, Uberti JP, Soiffer RJ, et al. Prochymal improves response rates in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(suppl 2):S169–S170. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou H, Guo M, Bian C, et al. Efficacy of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease: Clinical report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng JY, Du X, Geng SX, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell as salvage treatment for refractory chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1732–1740. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215–233. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soiffer R. Immune modulation and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(suppl 1):S66–S69. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Toy T, et al. B cells directly tolerize CD8(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1977–1983. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Hallek MJ, Storb RF, et al. The role of B cells in the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:4919–4927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-161638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kier P, Penner E, Bakos S, et al. Autoantibodies in chronic GVHD: High prevalence of antinucleolar antibodies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1990;6:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rickert RC, Jellusova J, Miletic AV. Signaling by the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily in B-cell biology and disease. Immunol Rev. 2011;244:115–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-cell biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackay F, Figgett WA, Saulep D, et al. B-cell stage and context-dependent requirements for survival signals from BAFF and the B-cell receptor. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:205–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarantopoulos S, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. High levels of B-cell activating factor in patients with active chronic graft-versus-host disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6107–6114. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutler C, Miklos D, Kim HT, et al. Rituximab for steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2006;108:756–762. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teshima T, Nagafuji K, Henzan H, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of corticosteroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Int J Hematol. 2009;90:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SJ, Lee JW, Jung CW, et al. Weekly rituximab followed by monthly rituximab treatment for steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease: Results from a prospective, multicenter, phase II study. Haematologica. 2010;95:1935–1942. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.026104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarantopoulos S, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. Recovery of B-cell homeostasis after rituximab in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2011;117:2275–2283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-307819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dorp S, Resemann H, te Boome L, et al. The immunological phenotype of rituximab-sensitive chronic graft-versus-host disease: A phase II study. Haematologica. 2011;96:1380–1384. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.041814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang AX, Yu WH, Ma BF, et al. Proteomic identification of differently expressed proteins responsible for osteoblast differentiation from human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;304:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu W, Chen Z, Zhang J, et al. Critical role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase cascade in adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;310:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, Li L, Liu Y, et al. Pleural fluid from tuberculous pleurisy inhibits the functions of T cells and the differentiation of Th1 cells via immunosuppressive factors. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:172–180. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Qiao D, Zhang X, et al. The immune responses of central and effector memory BCG-specific CD4+ T cells in BCG-vaccinated PPD+ donors were modulated by Treg cells. Immunobiology. 2011;216:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarantopoulos S, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. Altered B-cell homeostasis and excess BAFF in human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:3865–3874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanz I, Wei C, Lee FE, et al. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng L, Li L, Liu Y, et al. B lymphocytes that migrate to tuberculous pleural fluid via the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis actively respond to antigens specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3261–3269. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Socie G, Ritz J, Martin PJ. Current challenges in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(suppl):S146–S151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SJ, Won JH. B cell homeostasis and the development of chronic graft-versus-host disease: Implications for B cell-depleting therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:19–25. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.603448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greinix HT, Pohlreich D, Kouba M, et al. Elevated numbers of immature/transitional CD21- B lymphocytes and deficiency of memory CD27+ B cells identify patients with active chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pallier A, Hillion S, Danger R, et al. Patients with drug-free long-term graft function display increased numbers of peripheral B cells with a memory and inhibitory phenotype. Kidney Int. 2010;78:503–513. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newell KA, Asare A, Kirk AD, et al. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1836–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI39933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen JL, Fore MS, Wooten J, et al. B cells from patients with chronic GVHD are activated and primed for survival via BAFF-mediated pathways. Blood. 2012;120:2529–2536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.