Abstract

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) is an adverse drug reaction described as the progressive destruction and death of bone tissue of the mandible or maxilla, in the course of bisphosphonate therapy. Orally administered bisphosphonates, widely used for the treatment of osteoporosis, are rarely associated with BRONJ. Instead, the risk greatly increases whether the patient is concomitantly taking steroid and/or immunosuppressant agents. The aims of this paper are to briefly discuss the evidence of the associations between bisphosphonate therapy and BRONJ, and the effects of co-occurring factors such as the presence of rheumatoid arthritis, dental surgery, and concomitant corticosteroid therapy. In particular, we present the case of an elderly woman with BRONJ suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, with a recent dental extraction and with a very unusual complication: a temporal abscess, who was successfully treated.

Keywords: bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, BRONJ, adverse reaction, steroids

Introduction

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) is an adverse drug reaction described as the progressive destruction and death of bone that affects the mandible or maxilla of patients exposed to treatment with nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, in the absence of a previous radiation treatment.1 Currently, bisphosphonates are used in all cases in which it is deemed necessary to prevent bone resorption. They are administered by intravenous injection to treat metastatic osteolytic problems caused by several conditions (ie, multiple myeloma, bone metastasis by solid tumors with or without hypercalcemia, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, cancer of the kidney or lung, or Paget’s disease).2 They are also used in cases of low mineral bone density such as in post-menopausal osteoporosis or in osteopenia.3

All bisphosphonates, in particular the amino-bisphosphonates, have high affinity for bone mineral crystals and accumulate in the bone matrix. Bisphosphonates inhibit the enzyme farnesyl-diphosphate-synthase, causing cytoskeletal alterations, inducing apoptosis of the osteoclasts and reducing the bone resorption capacity of these cells.4–6 The half-life into the general circulation is short (from 30 minutes to 2 hours), but the presence of nitrogen in their formulation makes their metabolization difficult, leading to their accumulation in bones. Therefore, once the drugs are incorporated into bone tissue, they can persist for up to 10 years.7,8 Recent studies have shown that bisphosphonates inhibit oral epithelial cell migration, causing a delay of wound healing.9–12

Uncertain are the therapeutic possibilities, which up until today appear inadequate. Up until this point, no therapy exists which allows for the complete resolution/healing of lesion at 100%. Osteonecrosis involves only the maxillary bones, because these mostly undergo remodeling with respect to all the other bones in the body and present a higher uptake of bisphosphonates, which here become quickly concentrated and in higher quantities.1 The most affected parts are the mandible and, particularly, the alveolar bone. When in the bone, there has been an accumulation of bisphosphonates sufficient to reach the toxicity threshold for osteoclastic activity and migration inhibition, if surgical or inflammatory damage sets in, the alveolar bone is unable to react.13,14

There will be difficulty or absence of the healing process, leading to necrosis. The mucosa above begins to lack vascularization from the underlying bone, and bone exposition occurs. The consequence will be bacterial colonization with osteomyelitis. The bacterial strains isolated in the case of BRONJ, are the same that produce periodontal disease or dental abscesses. Actinomyces bacteria is the most frequently isolated strain.15

Local risk factors include extractions, dental implant placement, periapical surgery, and periodontal surgery involving bone injury. The threshold to inhibit wound bone healing depends on the total quantity of bone mineral in which bisphosphonates are stored: smaller sized patients are more affected than larger sized ones.16

Orally administered bisphosphonates require longer times for the development of BRONJ: 3 years according to Marx et al14 and 1 year in smaller sized patients, according to Sedghizadeh et al.16 The duration of bisphosphonate treatment and the potency of the drug, may also influence the risk of BRONJ. It should be noted that the association of two or more amino-bisphosphonates, and the association with corticosteroids, particularly prednisone taken by subjects affected by rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which mainly affects women, polimyosite, or systemic lupus erythematosus, certainly increases the risk of BRONJ setting in.

RA is considered an important contributing factor for BRONJ, even though the relationship between these diseases has not yet fully been understood. Bone tissue damage and loss are among the typical features of RA.17 The main factors that contribute to cause osteoporosis in patients with RA include glucocorticoid therapy and patient immobility.18,19 Corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis is the most common iatrogenic cause of secondary osteoporosis, and cumulative corticosteroid treatment increases the risk of osteoporosis: in fact 40% of these patients are affected by generalized osteoporosis, mostly after menopause.20 Studies on the effects of bisphosphonate therapy on bone loss due to RA indicate that bisphosphonates are effective in preventing bone loss in patients with RA treated with glucocorticoids. Results from the literature show that BRONJ is triggered by dental surgery procedures (51.7%) or lesions appearing spontaneously (41.38%) in patients affected by RA and treated with oral bisphosphonate.21

Case report

A 68-year-old woman was referred on January 2014 to the Department of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery of our hospital with difficulty on mouth opening, trismus, fever, headache, and general malaise. The patient’s past medical history was relevant for RA, treated from 1993 with gold salts, methotrexate, leflunomide, daily oral calcium and vitamin D3, and prednisone. From 2005, after multiple vertebral fractures caused by severe osteoporosis, the patient started a treatment with ibandronic acid, 150 mg, one tablet once a month. In March 2013, following an abscess in 46 zone, her dentist extracted the tooth element.

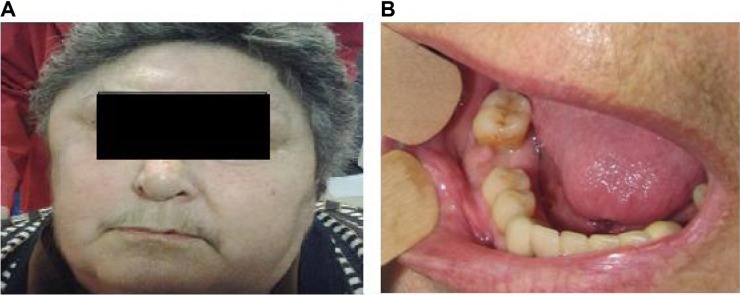

The patient showed a noticeable right-sided mandibular abscess and a right-sided soft temporal swelling and redness (Figure 1A), with severe pain on mouth opening.

Figure 1.

(A) Right-sided mandibular abscess and temporal swelling. (B) Abscess of the mandible affecting the extraction area. The pus is leaking from the empty alveolus. The infection and swelling extend to the second molar.

The oral examination revealed the presence of an abscess in the posterior mandible, in the area of the recent extraction (Figure 1B), with pus leaking from the empty alveolus. Infection and swelling was extending distally to the back molar 47.

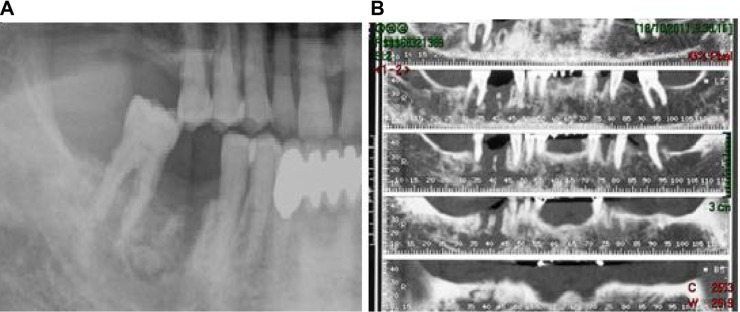

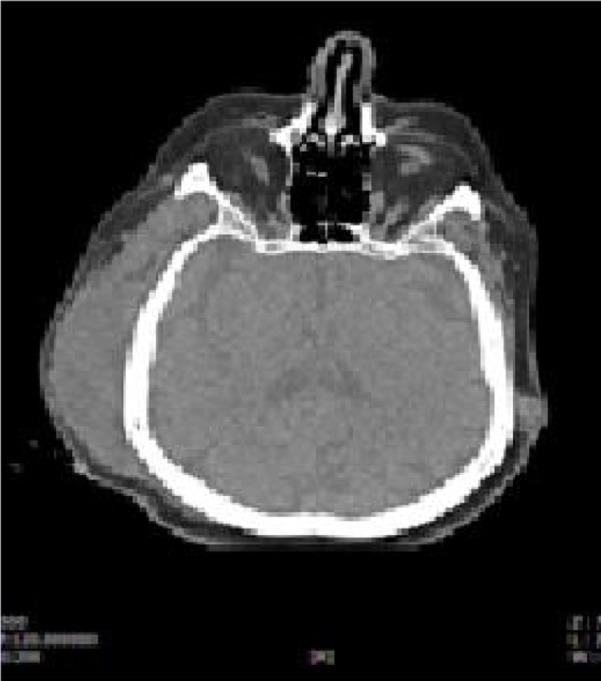

Radiologic exams (orthopantomography and CT [computed tomography] scan) (Figure 2A and B) showed a widespread zone of radiolucency, rarefaction of trabecular bone with a large osteo-necrotic lesion around the extraction site, which extended posteriorly to include the adjacent second molar, persistent extraction socket, and bone sequestra. All these data allowed us to diagnose advanced BRONJ in the right mandibular zone. Magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 3) showed a temporal abscess located lateral to the alveolar crista of the upper jaw and upwards deep into the temporal fascia.

Figure 2.

Panoramic (A) and mandibular (B) CT showing a zone of bone rarefaction. There is a large osteo-necrotic lesion around the extraction site adjacent to the second molar, with persistent extraction socket and bone sequestra.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography.

Figure 3.

Temporal abscess in the right zone.

Before admission to hospital, the patient was treated with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (875 mg and 125 mg respectively) injection.

After 2 days, a surgical toilette of necrotic bone in mandibular angle was performed with extraction of the second molar. The temporal fascia abscess was drained through a temporal incision. Microbiological samples showed an Actinomyces infection, with susceptibility to ampicillin, meropenem, and metronidazole, and with resistance to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Surgical incision was not saturated, and daily medication with irrigation on sodium hypochlorite and positioning of gauze of ialuronic acid was made twice a week. After microbiological analyses, which showed a resistance to antibiotic therapy, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid was substituted with meropenem 2 g and metronidazole 500 mg day.

After 3 weeks of therapy, the patient was discharged and was followed up monthly in our clinic. Three months after the hospitalization, the patient had complete resolution of infection.

Discussion and conclusion

While the correlation between use of intravenous injection bisphosphonates and the development of BRONJ is by now widely affirmed in the literature and was reported from 2003 by Marx,4 less clear and predictable is the correlation between BRONJ and orally administered bisphosphonates.22 What remains secure, however, is that dental surgical interventions on patients who take bisphosphonates on a long-term basis orally, present an elevated risk of BRONJ. The concomitant taking of medications containing corticosteroids, as in the case of RA, increases this risk due to the synergistic action of these drugs on the bone.

Corticosteroid medications act directly on the bone by inhibiting the action of osteoblasts, favoring that of the osteoclasts, and indirectly through hormonal pathways.23

The concomitant inhibitory action of bisphosphonates and corticosteroid drugs on bone and endothelial cells produce a reduction of the bone turnover rate. Following a surgical trauma due to extraction, this triggers BRONJ. In our case, osteonecrosis was already present before extraction of 46, which has highlighted the osteonecrotic zone.

The peculiarity of this case consisted of the rare localization of the abscess in the temporal position, which has considerably worsened the health status of the patient. This localization is extremely rare and this is the first case documented in the literature. It may happen that a dental abscess extends along muscles and fascia as occurs in the case of a parapharyngeal abscess or Ludwig’s angina; while it is very unusual, it spreads upward.24 This complication is very dangerous because of risk of thrombosis of the cavernous sinus, and it can even compromise the orbit.25

Although the extension of infection into the masticatory space has been observed to frequently extend superiorly against gravity, the pathway remains poorly understood.24,26 A submasseteric pathway aided by mastication forces has been proposed.24 This complication is presumably attributable to the declivous position, which the patient frequently used due to her current state of health. The patient, because she was a long-term sufferer of a severe form of RA, was confined to a wheelchair and bed.

All in all, BRONJ may be a potentially life-threatening condition occurring in patients on bisphosphonate therapy. This case-report emphasizes the importance of screening patients for BRONJ, when they are prescribed with bisphosphonates and concomitantly present further risk factors for BRONJ such as corticosteroid administration or oral surgery.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Campisi G, Lo Russo L, Agrillo A, Vescovi P, Fusco V, Bedogni A. BRONJ expert panel recommendation of the Italian Societies for Maxillofacial Surgery (SICMF) and Oral Pathology and Medicine (SIPMO) on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: risk assessment, preventive strategies and dental management. Ital J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;22:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B, Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;35:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2009.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) and the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:23–57. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little DG, Peat RA, Mcevoy A, Williams PR, Smith EJ, Baldock PA. Zoledronic acid treatment results in retention of femoral head structure after traumatic osteonecrosis in young Wistar rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2016–2022. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimachi K, Kajiya H, Nakayama S, Ikebe T, Okabe K. Zoledronic acid inhibits RANK expression and migration of osteoclast precursors during osteoclastogenesis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;383:297–308. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin TJ, Grill V. Bisphosphonates – mechanisms of action. Aust Prescr. 2000;23:130–132. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP. Bisphoshonates: molecular mechanisms of action and effects on bone cells, monocytes and macrophages. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2950–2960. doi: 10.2174/138161210793563635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pabst AM, Ziebart T, Koch FP, Taylor KY, Al-Nawas B, Walter C. The influence of bisphosphonates on viability, migration, and apoptosis of human oral keratinocytes – in vitro study. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi Y, Hiraga T, Ueda A, et al. Zoledronic acid delays wound healing of the tooth extraction socket, inhibits oral epithelial cell migration, and promotes proliferation and adhesion to hydroxyapatite of oral bacteria, without causing osteonecrosis of the jaw, in mice. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:165–175. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziebart T, Pabst A, Klein MO, et al. Bisphosphonates: restrictions for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis: inhibition of cell function of endothelial progenitor cells and mature endothelial cells in vitro. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozin M, Pinker BM, Solemani K, et al. Novel therapy to reverse the cellular effects of bisphosphonates on primary human oral fibroblasts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2564–2578. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landesberg R, Cozin M, Cremers S, et al. Inhibition of oral mucosal cell wound healing by bisphosphonates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CY, Pien FD, Suzuki JB. Identification and treatment of bisphosphonate-associated actinomycotic osteonecrosis of the jaws. Implant Dent. 2011;20:331–336. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3182310f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedghizadeh PP, Stanley K, Caligiuri M, Hofkes S, Lowry B, Shuler CF. Oral bisphosphonate use and the prevalence of osteonecrosis of the jaw: an institutional inquiry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:61–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breuil V, Euller-Ziegler L. Bisphosphonate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibuya K, Hagino H, Morio Y, Teshima R. Cross-sectional and longitudinal study of osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:150–158. doi: 10.1007/s10067-002-8274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haugeberg G, Orstavik RE, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK. Bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population-based cohort of 366 patients followed up for two years. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1720–1728. doi: 10.1002/art.10408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke BL. Corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:167–190. doi: 10.2165/11594250-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conte-Neto N, Bastos AS, Marcantonio RA, Junior EM. Epidemiological aspects of rheumatoid arthritis patients affected by oral bisphosphonate- related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Head Face Med. 2012;1:5–8. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mavrokokki T, Cheng A, Stein B, Goss A. Nature and frequency of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws in Australia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canalis E. Clinical review 83: Mechanisms of glucocorticoid action in bone: implications to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3441–3447. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuknecht B, Stergiou G, Graetz K. Masticator space abscess derived from odontogenic infection: imaging manifestation and pathways of extension depicted by CT and MR in 30 patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1972–1979. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim IK, Kim JR, Jang KS, Moon YS, Park SW. Orbital abscess from an odontogenic infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones KC, Silver J, Millar WS, Mandel L. Chronic submasseteric abscess: anatomic, radiologic, and pathologic features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1159–1163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]