Abstract

Services are available to help support existing employment for individual with psychiatric disabilities; however, there is a gap in services targeting job interview skills that can help obtain employment. We assessed the feasibility and efficacy of Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT) in a randomized controlled trial. Participants were randomized to VR-JIT (n=25) or treatment as usual (TAU) (n=12) groups. VR-JIT consisted of 10 hours of simulated job interviews with a virtual character and didactic online training. Participants attended 95% of lab-based training sessions and found VR-JIT easy-to-use and felt prepared for future interviews. The VR-JIT group improved their job interview role-play performance (p<0.05) and self-confidence (p<0.05) between baseline and follow-up as compared to the TAU group. VR-JIT performance scores increased over time (R-Squared=0.65). VR-JIT demonstrated initial feasibility and efficacy at improving job interview skills and self-confidence. Future research may help clarify whether this intervention is efficacious in community-based settings.

Keywords: psychiatric disability, virtual reality training, job interview skills, vocational training

Introduction

More than two-thirds of individuals with psychiatric disabilities (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) receiving mental health services want to work (Frounfelker et al, 2011; Ramsay et al, 2011). The United States employment rate was 90–95% over the past 5 years (U.S. Department of Labor, 2013), however, this rate is significantly lower among individuals with psychiatric disabilities (10–15%) (Rosenheck et al, 2006; Salkever et al, 2007). Supported Employment (SE) is an effective method to increase employment among individuals with psychiatric disabilities (Twamley et al, 2012) with an employment rate approaching 60% (Bond et al, 2008). However, there is limited access to SE, and 40% of consumers completing SE and individuals who never enroll in SE still struggle to find work. Thus, this population still faces major barriers to employment (Cook, 2006; Rosenheck et al, 2006).

Moreover, a 10-year follow-up study of SE indicated that only 30% of consumers felt that practicing job interviews was helpful (Salyers et al, 2004), which suggests that SE’s approach to improving job interview skills may have limited effectiveness. The SE manual disseminated by SAMSHA provides Employment Specialists (i.e., SE administrators) with educational materials to guide them in asking open-ended questions during a job interview role-play, which are conducted prior to scheduled job interviews. However, the manual does not provide guidance on how to conduct role-plays, how to “act” like a human resources representative with different moods or personalities, and on how much training is necessary to improve interview skills (SAMSHA, 2009).

Although the effectiveness of clinician-facilitated role-play training in vocational rehabilitation has received minimal empirical attention (Salyers et al, 2004), several interventions have been developed as supplements to enhance SE, including cognitive remediation, cognitive behavioral therapy, performance feedback, and developing work skills (Bell et al, 2003; Bell et al, 2008; Bowie et al, 2012; Lysaker et al, 2009; McGurk et al, 2005; Mueser et al, 2005). As such, perhaps SE or other vocational services can be enhanced by supplementing them with an evidenced-based approach to job interview training.

Few interventions have specifically targeted improving job interview performance for individuals with psychiatric disabilities looking for competitive employment (Bell et al, 2011). An important first step to gaining employment is successfully navigating the job interview. However, this process may be particularly difficult for individuals with psychiatric disabilities as they are typically characterized by impairments in social cognition (Couture et al, 2006; Dickinson et al, 2007; Lahera et al, 2012; Samame, 2013). Thus, the job interview process may be a critical target for vocational rehabilitation services, and as such, warrants further consideration (Bell et al, 2011).

Research suggests that navigating the job interview requires individuals to successfully convey job-relevant content during the interview (e.g., experience, core knowledge) and present a convincing performance during the interview (e.g., social effectiveness, interpersonal presentation) (Huffcutt, 2011). Thus, an intervention targeting these constructs could be effective at improving job interview performance for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Also, research has demonstrated that one’s self-confidence at interviewing has been associated with more effective verbal and nonverbal communication strategies during job interviews (Tay et al, 2006) and that low self-confidence is a barrier to employment among individuals with psychiatric disabilities (Corbiere et al, 2004; Provencher et al, 2002). These findings suggest that improving one’s self-confidence might enhance one’s job interview performance.

Although training using a traditional clinician-facilitated role-play method may have limited generalizability from the clinic to real world outcomes (Dilk et al, 1996), virtual reality (VR) training has demonstrated efficacy at improving interactive behavior and social skills that may transfer to actual conversations. For example, VR role-play simulations were developed to train federal law enforcement agents to perform interrogation techniques (Olsen et al, 1999), family physicians to perform brief psychosocial interventions (Fleming et al, 2009), and individuals with psychiatric disabilities to engage in more effective social skills (Park et al, 2011; Rus-Calafell et al, 2014). Moreover, simulation training has several advantages over traditional learning methods that have been applied to education and training (Cook et al, 2011; Issenberg et al, 2005). These include: 1) repetitive practice on simulated interactions, 2) exercises that allow trainees to practice new skills, 3) unique and individualized training experience with each simulated interaction, 4) consistent feedback in-the-moment, 5) enables trainees to address errors in a stress-free environment, 6) accurate representation of real-life interactions, 7) application of different skills and strategies as the level of difficulty increases (e.g., hierarchical learning), and 8) access to web-based didactic material to enhance learning (Issenberg et al, 2005). Hence, VR simulation role-play training is fundamentally different from the traditional clinician-based role-play methods that may be limited at training sustainable behavior.

Our aim in the present study was to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of a VR job-interview simulation program that was designed to improve job interview skills for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. The intervention, “Virtual Reality Job Interview Training” (VR-JIT), targets improvement of job relevant interview content and interviewee performance (Huffcutt, 2011). The VR-JIT prototype was tested on a small group of individuals with psychiatric disabilities to evaluate participant interest and ease of use [BLINDED AUTHOR CITATION]. Thus, the current study sought to examine the feasibility and efficacy of the full-version of VR-JIT in a randomized controlled trial.

Based on the findings from the evaluation of the VR-JIT prototype [BLINDED AUTHOR CITATION], we hypothesized that the VR-JIT sessions would be highly attended, and the intervention would be rated as easy to use, enjoyable, and helpful. We hypothesized that completion of VR-JIT training would be related to improvements in job interview role-play performance and enhanced self-confidence in job-interview skills in the VR-JIT group as compared to the TAU group. We explored whether job-interview role-play performance and self-confidence in one’s interview skills during follow-up assessments were associated with each other as well as with demographic characteristics, vocational history, and neurocognitive and social cognitive functioning.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 37 individuals with a psychiatric disability who were recruited through advertisements at community-based mental health service providers and [BLINDED INSTITUTION]. Participants were required to have a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to be included in the study. A B.S. or Ph.D.-level research staff using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) determined participant diagnoses (Sheehan et al, 1998). Participants were required to: 1) be 18–65 years old, 2) achieve at least a 6th grade reading level using the sentence comprehension subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test-IV (WRAT-IV) (Wilkinson et al, 2006)), 3) be video-recorded, 4) be unemployed or underemployed, and 5) be actively seeking employment.

The study exclusion criteria included: 1) having a medical illness that significantly comprised cognition (e.g., Traumatic Brain Injury), 2) uncorrected vision or hearing problem, or 3) a current diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence. The [BLINDED INSTITUTION] Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent. Once enrolled, participants were randomized into the intervention (n=25) or treatment-as-usual (TAU) group (n=12) at an estimated ratio of 2 to 1 due to limited resources.

Intervention

“Virtual Reality Job Interview Training” (VR-JIT) is a computer-based training simulation designed by SIMmersion LLC (http://www.simmersion.com) to improve job interview skills for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. VR-JIT adopts SIMmersion’s patented PeopleSIM™ technology, which uses video recordings to generate a virtual human character that interacts with trainees. The virtual character, Molly Porter, is a human resources representative at a large department store. Images of Molly and the VR-JIT interface can be found at http://www.jobinterviewtraining.net, a website designed to increase the distribution potential of VR-JIT. While the product was specifically designed for individuals with a range of disabilities (e.g., psychiatric, physical), integrated customization options allow it to be used by a general audience.

VR-JIT was designed to improve job interview skills by implementing the principles outlined by Issenberg and colleagues (2005) to design effective simulations as well as behavioral learning principles (Cooper, 1982; Cooper et al, 2007) that help promote sustainable changes in behavior (Roelfsema et al, 2010; Vinogradov et al, 2012). Specifically, VR-JIT allows trainees to 1) practice interviewing for the same or different jobs repeatedly until they are prepared for a real interview, 2) use speech recognition to speak their answers to questions rather than passively learn concepts (e.g., reading sample answers to questions), 3) answer questions specific to a job they want based on their own work history and skills, 4) an on-screen coach provides in-the-moment feedback using nonverbal cues and can be asked for additional help and suggestions during practice session, 5) practice recovering (e.g., apologizing or clarifying) from mistakes or erase them to try again without penalty, 6) engage with the interviewer who has memory and emotion, 7) try different approaches to answering questions that get harder as their skill increases (e.g., at a moderate level, the interviewer may ask follow up questions to clarify an answer and at the advanced level, she may ask an illegal question), and 8) didactic electronic learning (e-learning) materials that will help them with interviews and the other steps in finding a job (e.g., creating a resume, researching a position, what to wear, what types of questions to ask, selecting a job that meets their needs and deciding whether to disclose a disability, etc.). Also, job interviews are anxiety-provoking situations for most people, including individuals with psychiatric disabilities, who may be prone to anxiety (Braga et al, 2013; Pini et al, 1997). Simulated role-play training allows exposure to an anxiety-provoking situation in a safe environment where the trainee can exercise maximum control.

VR-JIT allows trainees to interview for 1 of 8 positions (i.e., cashier, stock clerk, customer service, maintenance/grounds, janitorial, food service, inventory, or security) at the department store each time they play the simulation. They are required to complete an on-line job application witht questions about past education, employment history, and job-related skills. Trainees also have the option to disclose the presence of physical disabilities (e.g., spinal cord injury, visible disability, hidden disability), history of mental illness, military history, past substance abuse, and prior criminal history. These questions allow Molly to personalize the training experience for each individual trainee by selecting relevant questions from her database of >1000 video-recorded questions range from general inquiries (e.g., “Tell me about yourself?”) to specifics about personal history (e.g., I noticed on your application that there are gaps in your work history. Can you tell me about that?) and job duties (e.g., This position will require you to work closely with other associates. Do you enjoy working as part of a team?).

The non-branching logic of PeopleSim creates dynamic links between Molly’s questions and the 2000 available responses, allowing trainees to try new approaches to answering questions during each interview. Molly’s simulated brain includes memory and a wide range of realistic emotions and personality that allow her to further tailor the interview to each trainee. For example, if someone applies for a customer service position and responds that he or she prefers to work independently, Molly may say, “That job requires that you work closely with others. Are you still interested in it or would you prefer something else?” The combination of trainee customization options and Molly’s realistic demeanor ensures that trainees experience a new interview each time they talk with her.

The variation in responses (to Molly’s questions) available to trainees can enhance or hurt rapport with Molly, allowing trainees to learn from mistakes, and creates a naturalistic conversation. VR-JIT also provides trainees with the opportunity to review a transcript of every simulated question and response, which indicates why responses were helpful or hurtful and gives related advice to the trainee. If the trainee is using the speech recognition feature, the transcript will replay a recording of the trainee’s voice answering the interview questions. Following each simulation, VR-JIT provides trainees with feedback on why certain training objectives received a particular score.

The simulated interviews have three difficulty levels where Molly is friendly (easy), business-oriented (medium), or brusque (hard). For example, the hard level presents a Molly who is unforgiving of errors and may even ask illegal questions. Also, Molly’s demeanor and questions continually evolves depending on the established rapport and the trainee’s prior responses. This emotional realism creates a dynamic experience in which trainees observe Molly become nicer when responded to honestly and respectfully, or observe her become curt and dismissive when responded to vaguely or rudely. These features, taken together with the scope of VR-JIT’s main components and non-branching logic, provide a comprehensive and interactive learning experience for practicing and performing a successful job interview.

Training Fidelity

Two research staff were trained to administer VR-JIT to trainees using a checklist, which covered: navigating the graphic user interface (GUI), creating a user profile, completing a job application, e-learning materials, starting the simulation, reading transcripts, using in-the-moment feedback and help modules, reviewing transcripts, and reviewing summarized interview performance. Staff engaged in practice sessions to prepare to administer VR-JIT to trainees in a standardized fashion. Participants were able to independently navigate VR-JIT after a 30–45 minute training session using the aforementioned checklist and no participants were excluded for an inability to navigate the training.

Study Procedures

The baseline assessments for both groups included 1) demographic, psychosocial, and vocational interviews; 2) clinical, neurocognitive, and social cognitive assessments; and 3) two standardized role-plays and a self-report of self-confidence. Following the completion of baseline assessments, the TAU group attended their typical outpatient vocational services for two weeks, which may have included preparations for job interviews using didactic and role-play methods. The intervention group was asked to complete 10 hours of VR-JIT simulations (approximately 20 trials) over the course of 5 visits (within a two-week period). Both groups returned after two weeks to complete the follow-up self-confidence measure, Treatment Experience Questionnaire (TEQ; VR-JIT group only) and two additional standardized role-plays (in that order).

Staff encouraged participants to review e-learning materials prior to each simulation, but referencing the e-learning component was not required. To promote hierarchical learning, participants were required to progress through three difficulty levels. They were required to complete at least three ‘easy’ interviews. One score of 80 or higher was required on ‘easy’ to advance to the ‘medium’ level. Participants automatically advanced to medium if they did not score at least 80 prior to 5 completed interviews. This process was repeated for participants at the ‘medium’ level before advancing to the ‘hard.’ Remaining trials were completed on the ‘hard’ level. The staff reviewed the transcript with the participants after each completed simulated interview, which lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Study Measures

Demographic Characteristics and Vocational History

The participants’ demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race), and vocational history (e.g., months since prior employment, prior vocational training) were obtained via a self-report interview.

Neuocognitive and Social Cognitive Measures

The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (Randolph et al, 1998) was administered to assess neurocognitive functioning. The total score of the RBANS reflects the following neurocognitive functions: immediate memory (i.e., list learning, story memory), visuospatial capacity (i.e., figure copy, line orientation), language (i.e., picture naming, semantic fluency), attention (i.e., digit span, coding), and delayed memory (list learning free recall, list learning recognition, story memory free recall, figure free recall). Additional details on these tests can be found here: http://www.rbans.com/testcontent.html.

We assessed basic and advanced social cognition using two tasks used in prior studies of adults with psychiatric disabilities. We assessed basic social cognition using the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT) (Bell et al, 1997). The BLERT requires participants to view twenty-one video-recorded vignettes of an affective monologue, and respond to which emotion is prominently displayed. An accuracy rating was computed based on the number of correct responses.

We assessed advanced social cognition using an emotional perspective-taking (EPT) task (Smith et al, 2013). Participants observed 60 scenes of 2 actors engaged in social interactions. The face of one actor was covered with a mask and participants were instructed to select which of two facial expressions would best reflect how the masked character would feel in the interaction. An accuracy rating was generated based on the number of correct responses.

The validities of the BLERT and EPT task have been reported previously (Derntl et al, 2011; Pinkham et al, 2013; Smith et al, 2013), while their internal consistencies are α=0.66 and α=0.56, respectively, in the current sample.

Feasibility Assessments

Participants were invited to attend five training sessions during which they could spend up to two hours receiving VR-JIT. We recorded participant attendance across the five training sessions and the number of minutes (out of a possible 600 minutes) that each participant engaged in the simulations.

Participants completed the TEQ (Bell et al, 2011) to evaluate the extent they felt VR-JIT was easy to use, enjoyable, helpful, instilled confidence in interviewing, and prepared them for interviews. The TEQ ‘s 5 items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting more positive views of VR-JIT. The TEQ had an internal consistency of α=0.71.

Primary Efficacy Assessments

Role-play job interviews

Interview role-plays (approximately 20 minutes each) were scored based on nine communication skills that contribute to successful job interviews: 1) conveying oneself as a hard worker (dependable), 2) sounding easy to work with (teamwork), 3) conveying that one behaves professionally, 4) negotiation skills (asking for Thursdays off), 5) sharing things in a positive way, 6) sounding honest, 7) sounding interested in the position, 8) comfort level, and 9) establishing overall rapport with the interviewer. These role-play scoring domains matched the feedback domains used in VR-JIT and are consistent with the job relevant interview content and interviewee performance constructs from the literature (Huffcutt, 2011).

Participants completed two role-plays at baseline and two role-plays at follow-up. They selected four of eight job scenarios and completed a job application to guide their role-play. The scenarios differed from the 8 jobs available during the intervention. They included: Data Entry Specialist at the Department of Public Health; Mail Clerk or Paralegal at a Law Firm; Medical Records Clerk at a Hospital; Inventory Manager or Stock Clerk at a Warehouse; Sales Associate at a Home Goods Store; or Reference Librarian at the Public Library. Participants were provided the following instructions prior to each interview: “You are interviewing for part-time work, particularly because you need to have Thursdays off for personal reasons. You will need to negotiate for a schedule that will accommodate for Thursdays off.” Interview role-plays were conducted by standardized role-play actors (SRAs) posing as human resources representatives and trained to ask 13 standardized questions, and 3–4 random questions from a list of 70+ questions, in a naturalistic way. The job scenarios were developed by the research team and vetted through a panel of vocational rehabilitation experts. All role-plays were video-recorded for scoring purposes.

Scoring role-play interviews

Videos were randomly assigned to two raters, with expertise in human resources, blinded to treatment group status. Raters were trained with 10 practice videos before independently rating the study videos. The raters established reliability with the study data by double scoring approximately 20% of the videos and attained a high degree of reliability (ICC=.85). In order to prevent rater drift, both raters met with the research team every 20 videos to review two videos and discuss inconsistencies and reach a consensus score. A total score was computed across nine domains (range of 1–5 per domain, with higher scores reflecting better performance) for each of the two baseline role-plays, and then averaged to compute a single score. A similar method was used to compute a single follow-up role-play score.

Job Interview Self-Confidence

Participants rated their self-confidence at performing job interviews using a 7-point Likert scale to answer nine questions, with higher scores reflecting more positive views (e.g., “How comfortable are you going on a job interview?” “How skilled are you at making a good first impression?” and “How skilled are you at maintaining rapport throughout the interview?”). Total scores at baseline and follow-up were computed. The internal consistencies at baseline (α=0.92) and follow-up (α=0.92) across all subjects were strong.

Process Measure

VR-JIT Performance

Participants’ VR-JIT performance scores and time spent engaged with the simulated interviews were recorded in the lab. The VR-JIT program scored each simulated interview from 0–100 using an algorithm programmed into the software based on the appropriateness of their responses throughout the interview in the following eight domains: negotiation skills (asking for Thursdays off), conveying you’re a hard worker (dependable), sounding easy to work with (teamwork), sharing things in a positive way, sounding honest, sounding interested in the position, acting professionally, and establishing overall rapport with the interviewer.

Data Analysis

Between-group differences for demographics, vocational history, global neurocognition, and social cognition were assessed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-Square analyses. We characterized VR-JIT feasibility with descriptive statistics of session attendance, the mean number of minutes required to complete the simulated interviews, and mean responses to the training experience questionnaire. We used a time-by-group interaction from a repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) to evaluate whether the primary outcome measures (role-play performance and job interview self-confidence) for the VR-JIT group significantly improved between baseline and follow-up as compared to the TAU group. Cohen’s d effect sizes were generated to characterize the within-subject differences between baseline and follow-up scores as well as between-group differences at follow-up.

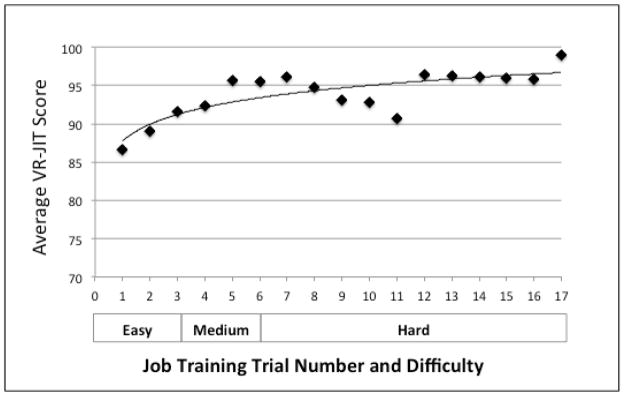

We evaluated VR-JIT performance score improvement across trials as a process measure by computing linear regression slopes for each subject based on the regression of their performance scores on the log of trial number. The group-level performance average for each successive VR-JIT trial was plotted with a report of the R-Square from the regression of average performance on the log of trial number.

We computed partial correlations in an effort to explore whether role-play and self-confidence scores at follow-up and VR-JIT performance slopes were associated with each other as well as with age, gender, months since prior employment, global neurocognition, and basic and advanced social cognition (while co-varying for baseline outcome scores).

The data were normally distributed and no transformations were necessary. Although participants were instructed to negotiate for Thursdays off during each role-play, they forgot during 16% of the role-plays despite prompting from the SRAs. The mean value of the other scores for this item was imputed for the missing variable (Myers, 2000; Sterne et al, 2009). No other role-play ratings were missing.

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at [BLINDED INSTITUTION] (Harris et al, 2009). REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.

Results

Between-Group Characteristics

The VR-JIT and TAU groups did not differ with respect to age at baseline, race, parental educational attainment, and neurocognitive and social cognitive functioning, the number of months since prior employment, previously held full-time employment, and prior participation in cognitive remediation or vocational rehabilitation (all p>0.10). Despite random assignment, the VR-JIT and TAU groups differed by gender (p<0.01) and the proportion of individuals with a major depressive disorder (MDD) (p=0.08) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample

| TAU Group (n=12) | VR-JIT Group (n=25) | χ2/T-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 44.3 (10.3) | 50.0 (11.6) | −1.5 |

| Gender (% male) | 16.7% | 64.0% | 7.3** |

| Parental education, mean years (SD) | 12.5 (2.4) | 14.1 (3.0) | −1.6 |

| Race | |||

| % Caucasian | 50% | 44.0% | |

| % African-American | 41.7% | 52.0% | 2.8 |

| % Asian | 8.3% | 0.0% | |

| % Latino | 0.0% | 4.0% | |

| Clinical History | |||

| % with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)a | 25.0% | 56.0% | 3.1+ |

| % with Bipolar Disorder Type I or II | 50.0% | 32.0% | 1.1 |

| % with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder | 25.0% | 12.0% | 1.0 |

| Vocational History | |||

| Prior full-time employment (%) | 75.0% | 88.0% | 1.0 |

| Prior paid employment (any type) (%) | 100% | 96.0% | 0.5 |

| Prior participation in vocational training program (%) | 25.0% | 32.0% | 0.2 |

| Months since any prior employment, mean (SD) | 47.2 (60.5) | 42.1 (43.4) | 0.3 |

| Cognitive function | |||

| Prior participation in cognitive remediation (%) | 0.0% | 12.0% | 1.6 |

| Global Neurocognition, mean (SD) | 91.3 (15.4) | 95.2 (19.9) | −0.6 |

| Basic Social Cognition, mean (SD) | .75 (.13) | .70 (.16) | 1.0 |

| Advanced Social Cognition, mean (SD) | .79 (.09) | .79 (.07) | 0.2 |

Note: TAU, treatment as usual participants; VR-JIT intervention participants.

n=1 TAU group has PTSD and MDD, n=1 VR-JIT group has PTSD and MDD.

p<.10,

p<0.01

VR-JIT Feasibility

The VR-JIT sessions were well-attended, and participants reported that VR-JIT was easy to use, enjoyable, helpful, increased their self-confidence in job-interview skills, and improved their readiness for interviewing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Feasibility Characteristics of VR-JIT Training, Mean (SD)

| Attendance Measures | |

| % Session Attendance | 95.2 (0.1) |

| Elapsed Simulation Time (min) | 564.6 (78.5) |

| Simulated Interviews (count) | 14.5 (3.2) |

| Training Experience Questionnaire | |

| Ease of use | 6.1 (0.9) |

| Enjoyable | 6.4 (1.0) |

| Helpful | 6.3 (1.1) |

| Instilled confidence | 6.0 (1.2) |

| Prepared for interviews | 6.0 (1.0) |

Note: SD, standard deviation; VR-JIT intervention participants.

Job Interview Role-Play Performance

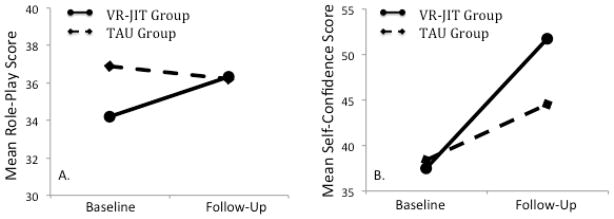

Results of the primary outcome RM-ANOVA analyses are presented in Table 3. The RM-ANOVA revealed a significant Group-by-Time interaction (F1,35=5.1, p≤0.05), but not a significant group effect at baseline (p>0.10). The VR-JIT group improved on the total role-play assessment score between baseline and follow-up (d=0.57), while the TAU group did not (d= −0.22) (Figure 1a). The follow-up role-play performances did not differ between groups at post-test (d= 0.02). The distributions of gender and MDD (or psychotic disorders) differed by group. Hence, they were evaluated independently as fixed-effects covariates. Neither variable had a significant main effect, time-by-gender or MDD interaction, or time-by-group-by-gender or MDD interaction (all p>0.10). Due to the observed non-significant effects, these variables were not included as covariates to maximize statistical power.

Table 3.

Change in Role-Play Performance and Job Interview Self-Confidence

| TAU Group | VR-JIT Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Baseline mean (SD) | Follow-Up mean (SD) | Cohen’s d | Baseline mean (SD) | Follow-Up mean (SD) | Cohen’s d | |

| Role-play performance | 36.9 (3.4)a | 36.2 (4.0) | −.22 | 34.2 (5.3)a | 36.3 (4.0) | .57 |

| Job interview self-confidence | 38.4 (13.2)b | 44.5 (8.2) | .81 | 37.5 (12.5)b | 51.8 (8.9) | 1.18 |

Note: TAU, treatment as usual participants; VR-JIT intervention participants.

Baseline role-play performance did not differ between groups (p>0.10).

Baseline job interview self-confidence did not differ between groups (p>0.10).

Figure 1.

Primary Outcomes. Panel A plots the significant Time-by-VR-JIT group interaction with regard to baseline and follow-up role-play scores. Panel B plots the trend-level Time-BY-VR-JIT group interaction with regard to baseline and follow-up self-confidence scores.

Job Interview Self-Confidence and Process Measure

The RM-ANOVA revealed a significant group-by-time interaction (F1,33=4.1, p≤0.05), but not a significant group effect (p>0.10) (Figure 1b). Although the interaction was significant at the trend level, both the VR-JIT and TAU groups demonstrated increased self-confidence characterized by large effects (d=1.18 and d= 0.81, respectively).

Our process measure indicated VR-JIT performance scores appeared to improve linearly with a dip about halfway through the hard trials, which suggests trainees may have spent a few trials learning about less appropriate responses (Figure 2). Specifically, the slope (mean=3.2, sd=3.8) suggests that performance improves 3.2 points for every 1 point increase in the natural log of the trial number (R-Squared= 0.65).

Figure 2.

VR-JIT learning curve in adults with a psychiatric disability. This figure plots the average score for each successive VR-JIT simulated interview trial. Trials 1–3 at easy, trials 4–6 at medium, and trials 7–17 at hard. Model fit, R2=0.65.

The exploratory correlations between the self-confidence, role-play, and process measures as well as with baseline variables within the VR-JIT group alone were not significant (all p>0.10), with the exception of age. VR-JIT performance scores were significantly correlated with age (r= −0.66, p<0.01), which suggests that younger participants have greater increases in VR-JIT performance scores per trial run.

Discussion

In this study, we examined whether VR-JIT demonstrated preliminary feasibility and efficacy in a small, randomized controlled trial of individuals with a psychiatric disability. The results suggest that VR-JIT can be feasibly implemented in a laboratory setting for individuals with a psychiatric disability as evidenced by completion of >95% of training sessions and >550 minutes of training (out of a maximum of 600 minutes). Participants indicated the intervention was very easy to use, highly enjoyable, helpful, instilled them with confidence, and made them feel well-prepared for future interviews. We also found that VR-JIT may be efficacious as our data suggested that the VR-JIT group had significantly higher scores on the role-plays at follow-up compared to baseline, trend-level increases in their self-reported self-confidence in their interview skills, and demonstrated significant improvement on their simulated role-play performances across increasing levels of difficulty. Although prior studies suggests that higher self-confidence may be related to better interview performance (Corbiere et al, 2004; Tay et al, 2006), we did not observe this relationship in the correlation analyses. This could be explained by a lack of power due to the small sample size or by limitations in the validity of the self-reported self-confidence measure given that both groups reported a large effect size increase in self-confidence. Hence, it is possible that both groups over-reported their confidence in the ability to succeed at a job interview.

The observed improvement of job interviewing skills (medium effect size) between the baseline and follow-up assessments is consistent with a recent study demonstrating improved job interview skills among individuals with autism while using VR training and role-play assessments (Strickland et al, 2013). Our results were also consistent with recent studies demonstrating that VR training using animated avatars can be used to improve vocational and social skills for individuals with psychiatric disabilities (Park et al, 2011; Rus-Calafell et al, 2014; Tsang et al, 2013; Zawadzki et al, 2013). Moreover, VR-JIT provided in-the-moment feedback, was rewarding, and was designed using behavioral learning principles with repetitive practice that allowed participants to build mastery as the simulated interviews progressively increased in difficulty. These design elements are critical features for interventions to train sustainable behavior (Kopelowicz et al, 2006; Roelfsema et al, 2010; Vinogradov et al, 2012).

The findings must be interpreted while considering some limitations. This sample was small and a larger sample could provide greater statistical power. For instance, we observed between-group differences in gender and diagnosis, which indicate that perhaps females or individuals with psychosis (i.e., bipolar or schizophrenia) may not benefit from the intervention. Although we observed these variables to be non-significant covariates, the study was underpowered. The baseline performance in the control group appeared higher (though non-significant) than the intervention group and the observed improvement in performance between baseline and follow-up in the intervention group could be interpreted as a regression to the mean given the small effect size difference between groups on post-test scores. Although subjects were randomly assigned and multiple baseline measure were obtained in an effort to prevent such threats to internal validity (Barnett et al, 2005), this finding must be interpreted with caution. Thus, it is possible that VR-JIT does not have a strong effect, however, future research with a larger sample would be needed to evaluate this issue more carefully.

In addition, the sample was older and the study was conducted in a laboratory setting. Further research is needed to gather data from a younger sample in a community setting to better establish the effectiveness of VR-JIT training. The specific outpatient services received by the TAU group were not identified, which may have contributed to their observed increased self-confidence ratings. Alternatively, the observed increase could be due to completing the role-plays. Furthermore, we did not observe a significant relationship between self-confidence ratings and role-play performance scores. Hence, participants could be over reporting their level of self-confidence, which would limit the validity of this measure.

This study suggests that VR-JIT might be feasible and efficacious across individuals with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. However, further research is needed to examine the impact of VR-JIT on each of these groups independently. We recruited participants who were actively seeking employment or competitive volunteer work. This approach may have created a self-selection sampling bias, but our participants represent the individuals most likely to use the software. Given that the heterogeneity of the sample may be a limitation, future research needs to assess whether VR-JIT may by efficacious for particular disorders. Future studies should also assess whether symptoms, pharmacological treatment, motivation, and length of time seeking employment impact the results of VR-JIT as these measures weren’t collected in the current study.

We did not track the use of the e-learning component or use of speech recognition, which could impact the utility of training and influence the participant’s learning, role-play performances, or VR-JIT performance scores. By tracking this data in future studies, we could more thoroughly assess how participants use and benefit from VR-JIT. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that interventions can be administered to psychiatric populations using mobile devices (Ben-Zeev et al, 2014; Ben-Zeev et al, 2013). Thus, future research could examine whether VR-JIT can be modified for use as a mobile device application in an effort to increase accessibility to trainees. Although we do not currently have employment outcome data for the participants in this study, future studies will examine whether VR-JIT is related to an increase in job interview frequency and finding a job.

Conclusions

In conclusion, VR training is a strategy that the field is developing to improve social cognition and assess community-based outcomes (Rus-Calafell et al, 2014; Zawadzki et al, 2013). This study demonstrated preliminary evidence that a VR approach to training job interview skills might be a feasible and efficacious tool to improve job interview performances and self-confidence in job interviewing for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Along these lines, future research could assess whether VR-JIT could effectively enhance Supported Employment (the gold standard for vocational rehabilitation (Becker et al, 2011; Bond et al, 2008)) as well as help individuals who do not have access to evidence-based vocational interventions. VR-JIT can reach a wide range of consumers of mental health services based on its use of a computerized platform (internet or desktop) to deliver VR simulations.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support

Support for this work was provided by a grant to Dr. Dale Olsen (R44 MH080496) from the National Institute of Mental Health with a subcontract to Dr. Michael Fleming at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

We would like to thank Dr. Zoran Martinovich for his consultation on the statistical analyses. The authors acknowledge research staff at Northwestern University’s Clinical Research Program for data collection and our participants for volunteering their time.

Sources of Funding

Dr. Dale Olsen received a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to develop VR-JIT (R44 MH080496), and funds were subcontracted to Dr. Michael Fleming at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine to support the NU team to complete the study. Dr. Olsen and Laura Boteler-Humm are employed by and own shares in SIMmersion LLC. They contributed to the manuscript, but were not involved in analyzing the data. Dr. Bell was a paid consultant by SIMmersion LLC to assist with the development of VR-JIT. Dr. Bell and his family do not have a financial stake in the company.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest outside of their salary support to complete the study.

References

- Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. International journal of epidemiology. 2005;34:215–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR. Benchmark outcomes in supported employment. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2011;14:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Bryson GA, Lysaker P. Positive and negative affect recognition in schizophrenia: a comparison with substance abuse and normal control subjects. Psychiatry research. 1997;73:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Lysaker P, Bryson GA. A behavioral intervention to improve work performance in schizophrenia: work behavior inventory feedback. J Vocat Rehabil. 2003;18:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Weinstein A. Simulated job interview skill training for people with psychiatric disability: feasibility and tolerability of virtual reality training. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(Suppl 2):S91–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Zito W, Greig T, Wexler BE. Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with vocational services: work outcomes at two-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev D, Brenner CJ, Begale M, Duffecy J, Mohr DC, Mueser KT. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of a Smartphone Intervention for Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2014 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev D, Kaiser SM, Brenner CJ, Begale M, Duffecy J, Mohr DC. Development and usability testing of FOCUS: a smartphone system for self-management of schizophrenia. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal. 2013;36:289–96. doi: 10.1037/prj0000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal. 2008;31:280–90. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, McGurk SR, Mausbach B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Combined cognitive remediation and functional skills training for schizophrenia: effects on cognition, functional competence, and real-world behavior. The American journal of psychiatry. 2012;169:710–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga RJ, Reynolds GP, Siris SG. Anxiety comorbidity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, Erwin PJ, Hamstra SJ. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:978–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA. Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: update of a report for the President’s Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1391–405. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO. Applied behavior analysis in education. Theory Into Practice. 1982;21:114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied Behavioral Analysis. London: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere M, Mercier C, Lesage A. Perceptions of barriers to employment, coping efficacy, and career search efficacy in people with mental illness. Journal of Career Assessment. 2004;12:460–478. [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2006;32(Suppl 1):S44–63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl B, Habel U. Deficits in social cognition: a marker for psychiatric disorders? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(Suppl 2):S145–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Bellack AS, Gold JM. Social/communication skills, cognition, and vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2007;33:1213–20. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilk MN, Bond GR. Meta-analytic evaluation of skills training research for individuals with severe mental illness. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64:1337–46. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming M, Olsen D, Stathes H, Boteler L, Grossberg P, Pfeifer J, Schiro S, Banning J, Skochelak S. Virtual reality skills training for health care professionals in alcohol screening and brief intervention. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2009;22:387–98. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.080208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frounfelker RL, Wilkniss SM, Bond GR, Devitt TS, Drake RE. Enrollment in supported employment services for clients with a co-occurring disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:545–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffcutt AI. An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 2011;19:62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Medical teacher. 2005;27:10–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590500046924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R. Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2006;32(Suppl 1):S12–23. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahera G, Ruiz-Murugarren S, Iglesias P, Ruiz-Bennasar C, Herreria E, Montes JM, Fernandez-Liria A. Social cognition and global functioning in bipolar disorder. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2012;200:135–41. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182438eae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Bryson GJ, Bell MD. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on work outcomes in vocational rehabilitation for participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia research. 2009;107:186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A. Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2005;31:898–909. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Aalto S, Becker DR, Ogden JS, Wolfe RS, Schiavo D, Wallace CJ, Xie H. The effectiveness of skills training for improving outcomes in supported employment. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1254–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers WR. Handling missing data in clinical trials: an overview. Drug Information Journal. 2000;34:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen DE, Sellers WA, Phillips RG. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Washington, D.C: 1999. The simulation of a human subject for law enforcement training. [Google Scholar]

- Park KM, Ku J, Choi SH, Jang HJ, Park JY, Kim SI, Kim JJ. A virtual reality application in role-plays of social skills training for schizophrenia: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatry research. 2011;189:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, Savino M, Russo A, Montgomery SA. Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Green MF, Buck B, Healey K, Harvey PD. The Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation Study: Results of the Expert Survey and RAND Panel. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher HL, Gregg R, Mead S, Mueser KT. The role of work in the recovery of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal. 2002;26:132–44. doi: 10.2975/26.2002.132.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay CE, Broussard B, Goulding SM, Cristofaro S, Hall D, Kaslow NJ, Killackey E, Penn D, Compton MT. Life and treatment goals of individuals hospitalized for first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry research. 2011;189:344–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1998;20:310–9. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema PR, van Ooyen A, Watanabe T. Perceptual learning rules based on reinforcers and attention. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2010;14:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, Stroup S, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163:411–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rus-Calafell M, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Ribas-Sabate J. A virtual reality-integrated program for improving social skills in patients with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry. 2014;45:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkever DS, Karakus MC, Slade EP, Harding CM, Hough RL, Rosenheck RA, Swartz MS, Barrio C, Yamada AM. Measures and predictors of community-based employment and earnings of persons with schizophrenia in a multisite study. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:315–24. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Becker DR, Drake RE, Torrey WC, Wyzik PF. A ten-year follow-up of a supported employment program. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:302–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samame C. Social cognition throughout the three phases of bipolar disorder: A state-of-the-art overview. Psychiatry research. 2013;210:1275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA); U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Supported Employment: Training Frontline Staff. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Helth Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Horan WP, Cobia DJ, Karpouzian TM, Fox JM, Reilly JL, Breiter HC. Performance-Based Empathy Mediates the Influence of Working Memory on Social Competence in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM, Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland DC, Coles CD, Southern LB. JobTIPS: A Transition to Employment Program for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1800-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay C, Ang S, Van Dyne L. Personality, biographical characteristics, and job interview success: A longitudinal study of the mediating effects of interviewing self-efficacy and the moderatin geffects of internal locus of causality. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:446–454. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang MM, Man DW. A virtual reality-based vocational training system (VRVTS) for people with schizophrenia in vocational rehabilitation. Schizophrenia research. 2013;144:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Vella L, Burton CZ, Becker DR, Bell MD, Jeste DV. The efficacy of supported employment for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2012;135:100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor; Bureau of Labor Statistics, editor. Labor Force Statistics From the Current Population Survey. 2013 http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

- Vinogradov S, Fisher M, de Villers-Sidani E. Cognitive training for impaired neural systems in neuropsychiatric illness. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:43–76. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzki JA, Girard TA, Foussias G, Rodrigues A, Siddiqui I, Lerch JP, Grady C, Remington G, Wong AH. Simulating real world functioning in schizophrenia using a naturalistic city environment and single-trial, goal-directed navigation. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2013;7:180. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]