Abstract

A ‘protein quake’ describes the hypothesis that proteins rapidly dissipate energy through quake like structural motions. Here we measure ultrafast structural changes in the Blastochloris viridis photosynthetic reaction center following multi-photon excitation using time-resolved wide angle X-ray scattering at an X-ray free electron laser. A global conformational change arises within picoseconds, which precedes the propagation of heat through the protein. This motion is damped within a hundred picoseconds.

Nature has evolved proteins to harvest both the energy and information content of light. Consequently, all light driven proteins share a common problem: how can the energy of an absorbed photon be usefully harvested without compromising the integrity of the protein when this energy is similar in magnitude to the protein's folding energy? Excess energy must be dissipated before irreversible damage occurs. The term ‘protein quake’ has been coined to describe how protein strain is released as a structural deformation that rapidly propagates away from a focus within the protein.1,2 Results from time-resolved spectroscopy3-6 have also suggested that the primary charge separation reactions of photosynthesis may be coupled to ultrafast protein structural changes. A deeper understanding of these phenomena requires experimental tools that directly probe protein conformational changes with picosecond time-resolution.

Time-resolved wide angle X-ray scattering (TR-WAXS) is a synchrotron based method that measures the nature and time-scale of global structural changes within proteins.7-14 The time-resolution at these sources is limited to 100 ps due to the electron bunch duration within a storage ring. In contrast, X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs) deliver extremely brilliant X-ray pulses a few tens of femtoseconds in duration.15 Here we use multi-photon excitation of the photosynthetic reaction center of Blastochloris viridis (RCvir, Supplementary Fig. 1) to demonstrate that TR-WAXS data recorded using XFEL radiation can capture an ultrafast protein conformational change that arises in picoseconds yet is rapidly damped.

Experiments were performed at the coherent X-ray imaging16 (CXI) experimental station of the Linac Coherent Light Source15 (LCLS) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Because of the extreme brilliance of XFEL radiation, for which 40 fs X-ray pulses containing 2.6 × 1012 photons/pulse were concentrated into a 10 μm2 focal spot, we injected samples of detergent solubilized RCvir across the XFEL beam using a gas focused liquid microjet17 (Fig. 1a). The jet velocity was approximately 10 m s−1 and so samples were translated several cm between each X-ray pulse; every XFEL pulse therefore interacted with a fresh RCvir sample and this avoided any build-up of laser or X-ray induced damage; both the XFEL repetition rate and the X-ray detector readout rate were 120 Hz and therefore WAXS data were recorded for each and every X-ray pulse; the 800 nm pump laser was operated at 60 Hz with dark and light images interleaved; the 800 nm laser path length through the microjet was ~ 10 μm giving a low sample optical density (OD800 nm~ 0.04) and ensuring homogeneous excitation; and the vacuum sample chamber removed background from air scattering. The major disadvantages of this experimental geometry were instabilities in the microjet and X-ray detector which led to more data being rejected from statistical criteria than is typical for TRWAXS studies at synchrotrons (Online Methods).

Figure 1.

Time dependent changes in WAXS data recorded from detergent solubilized samples of RCvir. (a) Schematic of the experimental setup illustrating the microjet of solubilized RCvir, X-ray detector, XFEL beam and the 800 nm pump laser. (b) Time-resolved WAXS difference data, ΔS(q, Δt) = Slight(q, Δt) - Sdark(q), recorded as a function of the time delay between the arrival of the 800 nm pump laser and the XFEL probe for 15 of 41 measured time delays. Linear sums of the four basis spectra (red) shown in d are superimposed upon the experimental difference data (black). (c) Time-dependent amplitudes of the components C1 to C4 used to extract the basis spectra. (d) Basis spectra extracted from the experimental data by spectral decomposition: C1, an ultrafast component (green); C2, a protein component (blue); C3, non-equilibrated (black) and C4, equilibrated (magenta) heating components.

Samples were photoactivated using 800 nm optical pulses of 500 fs duration and a pulse fluence of 5.3 mJ mm−2, which leads to considerable multi-photon absorption in RCvir (approximately 800 photons per RC molecule, Online Methods). Bacteriochlorophyll cofactors are highly resilient to high fluence and thus, despite the energy absorbed by every RCvir molecule being orders of magnitude above the activation energy of protein unfolding,18 photoexcited RCvir molecules largely survived undamaged in control experiments at a similar pump laser fluence (Supplementary Fig. 2). X-ray images were integrated in rings and difference scattering amplitudes (ΔS(q,Δt), photoactivated minus dark) were calculated as a function of the time delay (Δt) between the optical laser and XFEL pulses (Fig. 1b).

TR-WAXS data (Fig. 1b) were separated into their major components by spectral decomposition,8,11 which exploits differences in the rates of growth and decay of each component (Fig. 1c) to extract basis spectra (Fig. 1d). These data were described by a minimal set of four components: an ultrafast component (C1) that was set equal to ΔS(q,Δt) averaged over the first three time points after photoactivation; a protein component (C2) that displays oscillatory features characteristic of protein difference scattering7-14 (Supplementary Fig. 3); and non-equilibrated (C3) and equilibrated (C4) heating components. Since the photoactivated sample volume is thermally homogeneous within 100 ps, but which precedes thermal expansion,10 the equilibrated heating basis spectrum (C4) is almost identical to ΔS(q,Δt) averaged over the final three time-points. The temperature jump induced by the 800 nm pump laser was estimated to be 7 °C ± 1 °C by comparing ΔS(q,Δt) for the 280 ps time delay with temperature calibration WAXS curves measured using synchrotron radiation (Supplementary Fig. 4). All experimental data (Fig. 3b) were well approximated by a linear sum of the basis spectra C1 to C4 (Fig. 3a). Conversely, the time-dependence of the linear amplitudes of components C1 to C4 were well approximated by the modeled time-dependent amplitudes used to extract these basis spectra (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Structural analysis of the protein conformational changes. (a) Theoretical WAXS changes (red) predicted from χ2 fitting to the ultrafast basis spectrum (C1, black) where only movements of the RCvir cofactors were considered. (b) Theoretical WAXS changes (red) predicted from χ2 fitting to the protein basis spectrum (C2, black) where RCvir protein and cofactor atoms were allowed to move. (c) Stereo representation of light induced movements in RCvir. Large spheres represent Cα atoms that display recurrent movements within an ensemble of structural changes selected by χ2 fitting to C2 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Orange spheres represent Cα atoms with recurring movements away from other Cα atoms. No recurrent movements of Cα atoms towards other Cα atoms were identified. Cofactors are shown in grey.

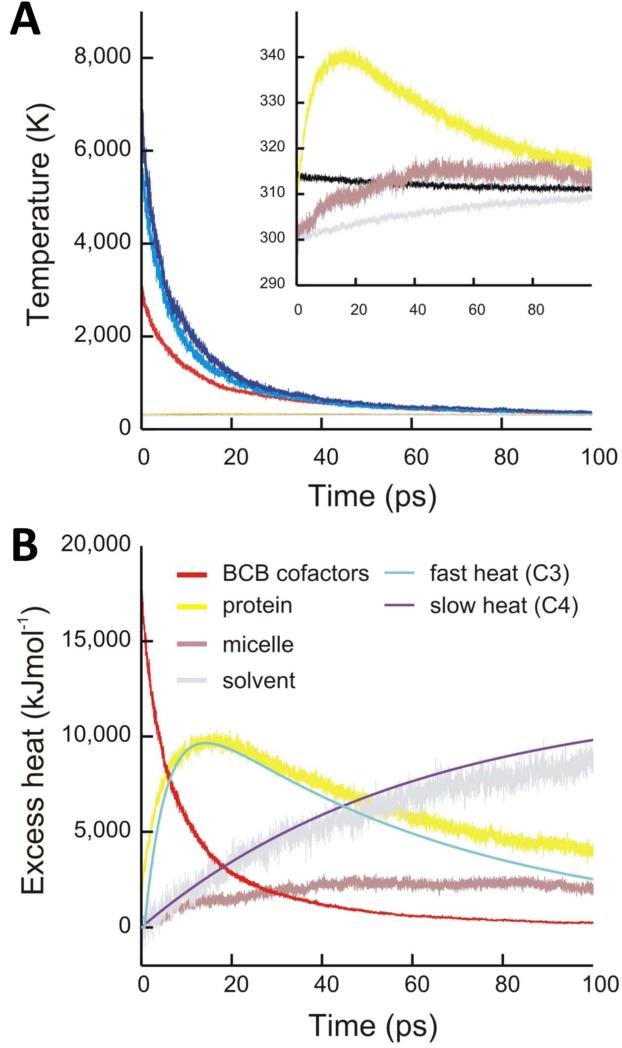

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of detergent solubilized RCvir with 15,000 kJ mol−1 of energy deposited into the bacteriochlorophyll cofactors were used to characterize the flow of heat from the bacteriochlorophyll cofactors into, and out of, the protein. This impulse instantaneously heated the cofactors by a few thousand Kelvin (Fig. 2a), which cooled by half within 7 ps as heat was dispersed into the surrounding protein, micelle and solvent. The time scale for when the heat content of the protein peaks as estimated by MD simulations (tmax = 14 ps, Fig. 2b) agrees strikingly well with the measured peak of the non-equilibrated heating component C3 (tmax = 14 ps, Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 5c). Similarly, the time-dependence of the experimental equilibrated heating component C4 agrees with the flow of heat out of the protein and into the surrounding solvent as predicted from MD simulations (Fig. 2b). We therefore conclude that C3 and C4 measure the flow of heat through the protein and into the surrounding media, respectively, and can be experimentally distinguished due to contrast between the temperature dependence of the protein and solvent WAXS spectra. Accordingly, heat conduction dissipates the protein's kinetic energy within a few tens of picoseconds, orders of magnitude faster than the time-scale characteristic of protein unfolding.7

Figure 2.

MD simulations of the flow of heat throughout the system. (a) Temperature of the cofactors (dark and light blue, bacteriochlorophylls; red, special pair), protein (yellow), detergent micelle (purple), surrounding solvent (grey) and total system (black) determined from MD trajectories. (b) Heat content of the cofactors (red), protein (yellow), detergent micelle (purple) and solvent (grey). The experimental amplitudes of the non-equilibrated heating (C3, light blue) and equilibrated heating (C4, dark blue) basis spectra are scaled to aid comparison with the heat content of the protein and solvent extracted from MD simulations.

Basis spectra C1 and C2 describe the protein's structural dynamics. The growth of C1, which has ΔS(q) negative below q ≤ 0.3 Å−1 but is otherwise featureless, was too rapid to be resolved (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and this component decayed by half within 3.2 ps. In contrast basis spectrum C2 contains oscillations in ΔS(q) between 0.2 Å−1 ≤ q ≤ 0.9 Å−1 (Fig. 3b), which are the fingerprint of protein structural changes as observed for bacteriorhodopsin on slower time-scales8 (Supplementary Fig. 3). These oscillations are not observed in WAXS difference data recorded from continuously heated RCvir samples (Supplementary Fig. 4a) nor in TRWAXS data recorded using synchrotron radiation (Supplementary Fig. 4b). We therefore conclude that C2 reveals an ultrafast protein conformational change that is half maximum Δt = 1.4 ps after photoactivation, peaks at Δt = 7 ps, and decays with a half-life of 44 ps. This structural deformation propagates away from the epicenter of the protein quake in advance of thermal diffusion, preceding the flow of heat into the protein by approximately 2 ps (Fig. 1c).

TR-WAXS is directly sensitive to protein structure and several groups have modeled conformational changes against difference WAXS data.8,9,11-14 Since no crystallographic structures exist to guide structural modeling on an ultrafast time-scale, we compared predictions recovered from photoexcited and reference MD simulations of RCvir against the ultrafast (C1) and protein (C2) difference WAXS basis spectra. This approach guarantees that all sampled structures are chemically accessible from the resting RCvir structure within a few ps after thermal energy is deposited into the protein's co-factors. Since heat is initially contained within the light-absorbing cofactors (Fig. 2), we performed χ2 fitting11 (Online Methods) to C1 by considering only motions of the bacteriochlorophyll cofactors, with the rest of the protein artificially frozen. The change in WAXS spectra predicted from a selected ensemble of 720 structural pairs is compatible with the C1 basis spectrum (Fig. 3a). For χ2 fitting to C2 we allowed motions of the entire protein and the WAXS changes predicted from the ensemble average of 720 selected structural pairs reproduces all major features of the difference WAXS basis spectrum (Fig. 3b).

Recurring movements were identified by calculating changes in the internal distance matrix on Cα atoms of photoexcited versus reference structures, [ΔCα]ij, averaging this matrix over an ensemble set identified by χ2 fitting, determining the standard deviation of this matrix over this ensemble set and examining the ratio of the average perturbation relative to its standard deviation (Supplementary Fig. 6). All recurring internal distance changes selected by this analysis (Online Methods, Supplementary Fig. 6) correspond to an increase of the internal distances between the Cα atoms of the protein's TM domains (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Video 1) and no recurrent movements of Cα atoms towards each other were identified. This shift in the ensemble average amounts to a modest (up to 1 Å in amplitude) expansion of the RCvir TM domain (Supplementary Video 2).

These data and its analysis establish that XFEL radiation facilitates the direct visualization of ultrafast protein motions using TR-WAXS. While acknowledging that our use of multi-photon excitation is far removed from physiological conditions, these X-ray snapshots of a ‘protein quake’ nonetheless show that strain created by energy input into the RCvir cofactors is relieved via a structural deformation that propagates through the protein more rapidly than heat. More experiments are needed to determine if similar motions are induced under physiological conditions of single-photon absorption. One interesting future application of XFEL based TR-WAXS is to search for phase coherent nuclear motions in photosynthetic reaction centers.3 Ultrafast motions may also be functionally important in other energy transducing proteins such as photosystems I and II, light harvesting complexes and bacterial rhodopsins;8,11 sensory receptors such as visual rhodopsin, sensory rhodopsin, photoactive yellow protein12 and phytochromes;14 or model heme containing proteins such as myoglobin9,10 and hemoglobin.7,13 Generic approaches that directly excite low-frequency normal-modes in proteins2,19 using short pulsed THz lasers20 will also facilitate ultrafast TRWAXS studies at XFELs that explore the rise and decay of global motions in any protein or macromolecular assembly of choice.

ONLINE METHODS

Protein Production and Purification

Bl. viridis cells were cultured in 10 l glass bottles. After two days of room temperature incubation in the dark, bottles were illuminated for two days at 30 °C and harvested using a JLA-8.1000 rotor at 8000 x g for 10 minutes. Approximately 30 g of cells were retrieved from 10 l of culture. Cell membrane was extracted through sonication, after which the membrane was pelleted by centrifugation at 45000 × g for 45 minutes. Membrane concentration was adjusted to OD1012 = 100 and solubilized in 4 % lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO) for 3 h at room temperature. Unsolubilized membrane was pelleted by centrifugation at 45000 × g for 75 minutes. Supernatant was transferred to a 250 ml POROS 50 micron HQ ion exchange media and fractions with A280/A830 ratio of ≤ 4 were pooled, concentrated to 10 ml using a 100 000 MWCO concentration tube and then loaded on a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 column. Fractions with A280/A830 ratio of ≤ 2.6 were pooled, concentrated to 30 mg ml−1 and flash-frozen for long term storage.

Data collection

Solubilized samples of RCvir were injected using a HPLC driven microjet17,21 with a nozzle diameter of 50 μm, a flow rate of 10 μl min−1, and achieving a jet diameter of 10 μm due to focusing by an outer stream of helium gas. The 800 nm fundamental of a Ti:Sa femtosecond laser was used to pump the sample using a pulse duration of 500 fs and pulse power of 260 μJ per pulse focused to a spot diameter for I/I0 = e−2 of 250 μm ± 25 μm. The selection of 500 fs pump pulse duration set the maximum temporal resolution accessible in this experiment. The pump laser had a Gaussian beam profile, with the average energy passing through the 250 μm circular focus corresponds to a fluence of 5.3 mJ mm−2.

Data were collected at the Coherent X-ray Imaging instrument16 (CXI) at the LCLS15 in January 2012. The XFEL pulse repetition rate and the detector readout rate were both 120 Hz, with a new image being recorded after every X-ray exposure. The Ti:Sa laser was run with a repetition rate of 60 Hz such that light (laser on) and dark (laser off) images were interleaved. Diffraction data were recorded on a Cornell-SLAC Pixel Array Detectors (CSPAD).22 The detector was built-up by 64 individual tiles with a pixel size of 110 × 110 μm2, each tile consisting of 192 × 185 pixels. The sample to detector distance was 107 mm and data were collected from q = 0.1 Å−1 to 2.5 Å−1.

The XFEL beam was tuned to 6 keV (wavelength 2.07 Å), focused to a spot size of 10 μm2 and aligned to intersect the liquid jet before the Rayleigh breakup. Spatial overlap of the XFEL and Ti:Sa laser beams on the microjet was aided by observing an X-ray induced fluorescence of the sample from the liquid jet. The flow rate of the microjet was ~10 m s−1 which ensured that every X-ray pulse sampled a completely fresh sample, thereby avoiding all issues concerning 800 nm laser or XFEL induced accumulated damage to the sample. A preliminary analysis of the TR-WAXS data implemented during the experiment allowed the difference signal, ΔS(q, Δt), to be displayed approximately two minutes after data were collected. From this difference signal the temporal overlap was set (Δt = 0 ± 0.5 ps) at the precise location of the microjet. The experimental necessity (at the time) to use ΔS(q) to establish Δt = 0 motivated our choice of a high pump laser fluence in these experiments.

Sample heating

The temperature jump induced by the pump laser within the sample volume under these conditions was 7 ± 1 °C and was determined by comparison of the change in X-ray scattering in these experiments for Δt = 280 ps over the domain 1.0 ≤ q ≤ 2.5 Å−1 against standard heating curves recorded using synchrotron data10 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Because of shot-to-shot fluctuations in background in the XFEL data, the temperature calibration curves recorded using synchrotron data were first interpolated in 1 °C steps over the temperature domain 0 °C ≤ ΔT ≤ 20 °C and 500 random numbers were then added to generate an ensemble of mock temperature measurements with random background fluctuations. The closest agreement to the XFEL data was for ΔT = 7 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The time-resolved data recorded using synchrotron radiation established that ΔS(q, Δt = 280 ps) ≈ ΔS(q, Δt = 1 μs) (Supplementary Fig. 4b) which justifies this calibration, since the sample is fully expanded and in thermal equilibrium for Δt = 1 μs10,23 and can therefore be compared against standard temperature calibration curves.

A temperature jump of ΔT = 7 ± 1 °C corresponds to 800 ± 100 photons absorbed per RCvir molecule within the sampled volume, which is far removed from normal physiological conditions. The RCvir molar extinction coefficient24 is high at 800 nm (ε800 nm ~ 1.8 × 105 ± 0.2 × 105 M−1 cm−1) such that, assuming an incident laser fluence of 5.3 mJ mm−2, approximately 800 photons would be absorbed per RCvir molecule if 55 % of the incident light were scattered from the microjet. In reality the photochemistry is more complex since high photon-flux densities cause exciton annihilation25,26 resulting in one electronically deexcited and one highly excited species. Moreover, highly excited species undergo rapid radiationless relaxation into vibrational modes according to Kasha's rule27 and it is very difficult to reach high lying electronic states because the more excited the molecule becomes the more rapidly it decays through vibrational coupling.

Data analysis

Radially integrated stacks of each run were extracted using Cheetah software (https://github.com/antonbarty/cheetah) and difference scattering curves were obtained using MatLab. Radially integrated data were normalized between q = 2.10 to 2.20 Å−1. Three 3σ criteria rejection routines were performed on this data: an initial rejection on the absolute scattering data; a second rejection on the normalized data; and a final rejection on the difference curves. Approximately 9000 differences measurements were thus merged for each time point representing approximately 60 % of all recorded data, which is a smaller fraction than typically kept when using synchrotron radiation (~ 95 %).

A total of 41 difference WAXS traces, ΔS(q,Δt), for 41 different time-delays, Δt, between the arrival of the 800 nm optical laser and X-ray laser pulses, were processed by spectral decomposition.8 Spectral decomposition is similar to principle component analysis but specifies the time-dependence of the states to be extracted according to a kinetics scheme (Fig. 1c). Four components were extracted from the data (Fig. 1d): an ultrafast component (C1); a second component identified as due to protein conformational changes (C2); and two heating components: non-equilibrated (C3) and equilibrated (C4). All components were modeled as simple first-order kinetics (exponential rise and decay) with the decay of the C3 heating component being coupled to the growth of the C4 heating component (ie. C3 → C4) and a time offset of approximately 2 ps was needed to fit the rise of C3. We initially focused on the time-dependence of WAXS differences within the domain q = 1.35 to 2.5 Å−1 so as to extract the time-dependence of the components C3 and C4; and ΔS(q) averaged over the first three time points was used to define C1. Iterative cycles of subtracting the C3, C4 and C1 basis spectra from the WAXS data so as to characterize the C2 component; followed by removing the C2 component from all data so as to better characterize the C3 and C4 basis spectra; yielded the optimal basis spectra (Fig. 1d). All four components were used to reproduce the entire data set as a linear sum of these components (Fig. 1b) and to validate the kinetic model used for spectral decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 5).

On the picosecond time-scale it might be expected that a description of these data in terms of four time-independent functions (C1(q) to C4(q)) with time-dependent amplitudes may break down since a localized perturbation in real space corresponds to a delocalized response in q space that evolves in time. This simple description, however, proved to be satisfactory given the errors within this experimental data (Fig. 1b) although future analysis of TR-WAXS studies of ultrafast protein dynamics may require modifications to this scheme.

Synchrotron based data collection

Difference WAXS data for both steady-state heating (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and for the time-points Δt = 280 ps and 1 μs (Supplementary Fig. 4b) were recorded at the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory (APS) using the setup as described.10 Steady state measurements used an Oxford cryostream to heat the sample as it flowed through a capillary; and time-resolved WAXS measurements used 100 ps X-ray pulses isolated using a microsecond chopper28 and a 780 nm picosecond laser to excite the sample.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Reaction center coordinates were taken from the 2.3 Å X-ray structure of detergent solubilized RCvir29 (pdb entry 1PRC). All interactions were modeled with the Amber03 force field30. Bonded and Lennard-Jones parameters used to model the co-factors bacteriochlorophyll B, bacteriophytin B, menaquinone and ubiquinone, were taken from Cecarelli and co-workers31, who derived the these parameters for bacteriochlorophyll A, bacteriophytin A and ubiquinone, the cofactors in the reaction center of R. sphaeroides (RCsph). Because the same atom types occur in the cofactors in RCsph and RCvir, we constructed new force fields for bacteriochlorophyll B, bacteriophytin B and menaquinone based on the atomtype information provided by Cecarelli et al.31. Partial charges were rederived for all atoms of the co-factors, following Amber03 charge parameterization philosophy30. The structures of the isolated co-factors, without their aliphatic tails (for which the default Amber03 charges were used) were minimized at the HF/6-31G** level of ab initio theory. To include the effect of the protein environment in these calculations, the IEFPCM continuum solvent model was used with a relative dielectric of 4. After geometry optimization, the electrostatic potential at 10 concentric layers of 17 points per unit area around each atom was evaluated using the electron density calculated at the B3LYP/cc-pVTZ level of theory, again using the IEFPCM continuum solvent model with a relative dielectric of 4. The atomic charges were obtained by performing a two stage RESP fit to the electrostatic potential. The force field parameters for the Heme(III) co-factors were taken from Authenrieth and co-workers32 without modifications. Gromacs topology files and starting coordinates are available for download from wwwuser.gwdg.de/~ggroenh/RC_vir.tar.gz.

The RCvir structure was minimized in vacuum using infinite cut-offs for both Lennard-Jones and Coulomb interactions. After minimization, the protein complex was embedded into a micelle that was composed of LDAO detergent molecules. Following the estimates of Gast et al.33, 260 detergent molecules were used to solvate the TM portion of the protein. After insertion, around 187 Na+ and 188 Cl− ions were added to the water phase to create a 0.2 M salt solution. The total system contained 145,368 atoms and was equilibrated for 20 ns with harmonic position restraints on the heavy protein and co-factor atoms (force-constant 1000 kJmol−1nm−2). After releasing these restraints, the system was further equilibrated for 14 ns.

Equilibration simulations were run at constant pressure34 and temperature35 with time constants of 1.0 ps and 0.1 ps for the pressure and temperature coupling, respectively. The LINCS algorithm was used to constrain bond lengths36, allowing a time step of 2 fs in the classical simulations. SETTLE was applied to constrain the internal degrees of freedom of the water molecules. A 1.0 nm cut-off method was used for non-bonded Van der Waals’ interactions, which were modeled by Lennard-Jones potentials. Coulomb interactions were computed with the smooth particle mesh Ewald method37 using a 1.0 nm real space cut-off and a grid spacing of 0.12 nm. The relative tolerance of the real space cut-off was set to 10−5. All simulations were performed in double precision with the Gromacs-4.5.4 molecular dynamics program.38

After equilibration, the simulation was continued for 5 ns in the NVE ensemble by switching off both temperature and pressure coupling. Only water molecules were constrained using SETTLE, while no constraints were used for the protein or micelle. The time step was reduced to 0.25 fs. Real-space cut-offs were shifted after 0.9 nm and the PME grid spacing was reduced to 0.11 and the relative tolerance was set to 10−6. From the 5 ns NVE trajectory snapshots were taken every 100 ps to serve as starting points for the heat-transfer simulations.

To model the effect of the multi-photon absorption by the bacteriochlorophyll B co-factors, we assigned new velocities to the co-factor atoms. These velocities were randomly chosen from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at an elevated temperature. This temperature was calculated under the assumption that all photons are converted into kinetic energy:

where i identifies the cofactor (special pair or one of the auxiliary bacteriochlorophylls), Ni the number of atoms in the co-factor, vi the absorption frequency of co-factor i taken from Breton et al.39, kB the Boltzmann and mi, the number of photons absorbed by cofactor i. For MD simulations we assumed that the special pair and the two auxiliary bacteriochlorophylls absorb 100 photons each. Although other cofactors may have absorbed some photon energy, this assumption is not considered to be severely limiting for this analysis since the energy rapidly flows out of the superheated cofactors into the protein (Fig. 5a), and the MD trajectories provide a large number of structures used for structural fitting. After assigning the new velocities to the co-factor atoms, the simulations were continued from the snapshots.

To monitor the flow of heat the system was divided into four subsystems: cofactors, protein, micelle and solvent. Excess heat Qi(t) in subsystem i was defined as the difference between total kinetic energy in these subsystems after multiple photon absorption and the average total kinetic energy in these systems in the equilibrium simulation at 300 K:

Excess heat curves (Fig. 3) were obtained by averaging Qi(t) over 38 simulations. The temperature of the total system is not conserved with time (Fig. 1a) since some energy initially deposited into the cofactors is converted into potential energy within the system.

Structural refinement

Structural refinements against the C1 (ultrafast) and C2 (protein) basis spectra (Fig. 1d) were performed by χ2 fitting of WAXS difference spectra using the error weighted χ2 scoring function described in Malmerberg et al..11 WAXS difference spectra were calculated from the set of pdb structures generated from MD simulations. 1000 pdb snapshots were extracted at 100 fs intervals from each of 36 photo-excited and 36 reference MD trajectories. X-ray scattering calculations compared MD trajectories of photo-excited structures (energy deposited into the bacteriochlorophyll cofactors at t = 0 ps) against reference structures (no energy deposited) for which the paired trajectories both started from the same initial structure. Difference WAXS spectra, ΔStheory(q), were calculated using the Debye formula and evaluated for their agreement with the C1 and C2 basis spectra using χ2 scoring. Theoretical fits (Fig. 3a and 3b) represent an average of the best 20 predictions for each of 36 trajectories: an ensemble average prediction from 720 structural pairs in total. Ensemble averaging was used since one should not visualize the laser pump as causing a light-induced shift from one static structure to another. Instead, dynamical motions occur within the protein on the picosecond time-scale that are larger than the light-induced perturbation to the ensemble average and it is a shift in the average distribution of an ensemble that is probed by TR-WAXS.

For structural fitting of C1 (the ultrafast component) only movements of the atoms of the bacteriochlorophyll cofactors were considered: specifically the atomic positions of these cofactors were extracted from the photoexcited and reference MD trajectories but all other atoms were frozen at their t = 0 conformation when calculating ΔStheory(q). The resulting ensemble fit (Fig. 3a) supports our hypothesis that this component stems from ultrafast laser induced heating of the cofactors. For structural fitting of C2 (the protein component) all protein and cofactor atoms were allowed to move: specifically the atomic positions of all atoms were extracted from the photoexcited and reference MD trajectories when calculating ΔStheory(q). The resulting ensemble fit (Fig. 3b) supports our hypothesis that the C2 component reflects an ultrafast global conformational change in RCvir. Since the ratio of observations to variables is not favorable in TR-WAXS, these solutions are consistent with the data but are not necessarily unique since it cannot be ruled out that other conformations not sampled in our MD trajectories might yield analogous agreement to the TR-WAXS data.

Corrections to the WAXS patterns due to the presence of a detergent micelle and the excluded solvent volume were performed using the same assumptions as described when fitting time resolved WAXS spectra of bacteriorhodopsin and proteorhodopsin.8,11 In particular, the dynamics of the detergent micelle were not modeled per se, but rather an average scattering detergent micelle correction was extracted from the reference trajectory and this correction was applied to both the photoexcited and referenced ΔS(q) calculations. Although this proved to be a critical assumption for structural refinement, since it avoided the fitting routine becoming dominated by movements of the detergent molecules within the micelle, the limitations of this assumption may contribute in part to a discrepancy between ΔStheory(q) and ΔSexperiment(q) for q ≤ 0.2 Å−1. Fluctuations in the microjet, which causes stronger scattering at low q, also contributed experimental error in this domain.

No two pair of structures (photoexcited versus reference) selected by χ2 fitting against the C2 basis spectrum gave identical structural changes. Recurring structural changes were identified by accepting that although all parts of the protein vary during MD simulations, the underlying global structural change should be present (at least to some extent) within all of the best pairs identified by χ2 analysis. To extract these recurring structural changes from the ensemble of 900 best fits (the best 50 pairs from 18 paired MD trajectories of photoexcited and reference RCvir) we first calculated a matrix [ΔCα]ij of the change in the internal distances between Cα atoms ([ΔCα]ij = [Cαphotoexcited - Cαreference]ij, where ij label all Cα atoms of RCvir). We then determined the average, Avg([ΔCα]ij), and the standard deviation, [σ(ΔCα)]ij, of this ensemble set of 900 matrices. Finally we applied thresholds for which a movement was characterized as recurrent, requiring that the magnitude of the average internal distance matrix change was at least 90 % of the standard deviation of this change, Avg([ΔCα]ij) ≥ 0.9 × [σ(ΔCα)]ij, and that each selected Cα atom has at least 20 internal distance changes above this threshold. These Cα atoms and the sign of their movements are highlighted graphically (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Video 1). Two striking features emerge from this analysis: only movements of two Cα atoms away from each other (ie. Avg([ΔCα]ij) ≥ 0, orange spheres in Fig. 3c) were identified as recurrent, with no case being identified for which two Cα atoms moved towards each other passing these thresholds; and almost all Cα atoms identified in this manner were associated with the TM domains of subunits H, L and M (Fig. 3c).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Experiments were carried out at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Swedish Science Research Council (VR), the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), the Swedish Strategic Research Foundation (SSF), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and its bioXFEL Science and Technology Center (NSF 1231306), the US National Institute of Health (NIH), the DOE Office of Basic Energy Sciences, the Hamburg Ministry of Science and Research, the Joachim Herz Stiftung, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship of the European Union, the Academy of Finland, and the Max Planck Society, the Danish National Research Foundations Centre for Molecular Movies, DANSCATT, the UCOP Lab Fee Program (award no. 118036) and the LLNL Lab-directed Research & Development Program (12-ERD-031).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.N. and D.A. conceived the experiment which was designed with E.M., J.D., A.B., H.N.C., J.C.H.S., S.Bo., G.W., D.d.P., R.B.D. and U.W.. Samples were prepared by D.A. and L.C.J.; Time resolved WAXS experiments at the LCLS were performed by D.A., L.C.J., A.B., G.W., C.W., E.M., J.D., D.M., D.d.P., R.L.S., D.W., D.J., G.K., S.W., T.A.W., A.A., S.Ba., M.B., R.B.D., M.F., R.F., I.G., M.S.H., R.A.K., C.K., M.L., A.V.M., M.M., M.M.S., J.S., F.S., U.Q., N.A.Z., P.F., I.S., S.Bo., H.N.C. and R.N. Time resolved WAXS experiments at Argonne National Laboratory were performed by D.A., L.C.J., P.B., J.S., J.D., R.H. and I.K.. The CXI instrument was setup by S.Bo., G.J.W., M.M. and M.M.S and the online fs laser was setup by D.M., J.D. and M.F.. Samples were delivered by R.L.S., S.Ba., D.d.P., U.W. and R.B.D. Data were analyzed by D.A., A.B., E.M. and C.W. Molecular dynamics simulations of RCvir were performed by G.G., theoretical fitting by D.A. and C.W., and heat flow dynamics examined by G.G. K.S.K., T.v.D. and M.M.N. The manuscript was prepared by R.N., D.A. and G.G. with input from all authors.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Methods website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansari A, et al. Protein states and proteinquakes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:5000–5004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyashita O, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Nonlinear elasticity, proteinquakes, and the energy landscapes of functional transitions in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12570–12575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135471100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos MH, Rappaport F, Lambry J-C, Breton J, Martin J-L. Visualization of coherent nuclear motion in a membrane protein by femtosecond spectroscopy. Nature. 1993;363:320–325. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rischel C, et al. Low frequency vibrational modes in proteins: changes induced by point-mutations in the protein-cofactor matrix of bacterial reaction centers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:12306–12311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, et al. Protein dynamics control the kinetics of initial electron transfer in photosynthesis. Science. 2007;316:747–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1140030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, et al. Unusual temperature dependence of photosynthetic electron transfer due to protein dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:818–824. doi: 10.1021/jp807468c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cammarata M, et al. Tracking the structural dynamics of proteins in solution using time-resolved wide-angle X-ray scattering. Nat. Meth. 2008;5:881–886. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson M, et al. Structural dynamics of light-driven proton pumps. Structure. 2009;17:1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn S, Kim KH, Kim Y, Kim J, Ihee H. Protein tertiary structural changes visualized by time-resolved X-ray solution scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:13131–13133. doi: 10.1021/jp906983v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho HS, et al. Protein structural dynamics in solution unveiled via 100-ps time-resolved x-ray scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7281–7286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002951107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malmerberg E, et al. Time-resolved WAXS reveals accelerated conformational changes in iodoretinal-substituted proteorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1345–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramachandran PL, et al. The short-lived signaling state of the photoactive yellow protein photoreceptor revealed by combined structural probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9395–9404. doi: 10.1021/ja200617t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KH, et al. Direct Observation of Cooperative Protein Structural Dynamics of Homodimeric Hemoglobin from 100 ps to 10 ms with Pump-Probe X-ray Solution Scattering. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7001–7008. doi: 10.1021/ja210856v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takala H, et al. Signal amplification and transduction in phytochrome photosensors. Nature. 2014;509:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emma P, et al. First lasing and operation of an angstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photon. 2010;4:641–647. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutet S, Williams GW. The Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). New J. Phys. 2010;12:035024. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weierstall U, Spence JC, Doak RB. Injector for scattering measurements on fully solvated biospecies. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012;83:035108. doi: 10.1063/1.3693040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palazzo G, Lopez F, Mallardi A. Effect of detergent concentration on the thermal stability of a membrane protein: The case study of bacterial reaction center solubilized by N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go N, Noguti T, Nishikawa T. Dynamics of a small globular protein in terms of low-frequency vibrational modes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:3696–3700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook DJ, Hochstrasser RM. Intense terahertz pulses by four-wave rectification in air. Opt. Lett. 2000;25:1210–1212. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.001210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DePonte DP, et al. Gas dynamic virtual nozzle for generation of microscopic droplet streams. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2008;41:195505. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart P, et al. The CSPAD megapixel x-ray camera at LCLS. Proc. SPIE. 2012;8504:85040C. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgiou P, et al. Picosecond calorimetry: Time-resolved X-ray diffraction studies of liquid CH2Cl2. J. Chem. Biol. 2006;124:234507. doi: 10.1063/1.2205365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton RK, Clayton BJ. Molar extinction coefficients and other properties of an improved reaction center preparation from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;501:478–487. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(78)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valkunas L, Gulbinas V. Nonlinear exciton annihilation and local heating effects in photosynthetic antenna systems. Photochem. Photobiol. 1997;66:628–634. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valkunas L, Trinkunas G, Liuolia V, van Grondelle R. Nonlinear annihilation of excitations in photosynthetic systems. Biophys. J. 1995;69:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79986-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasha M. Characterization of Electronic Transitions in Complex Molecules. Disc. Faraday Soc. 1950;9:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cammarata M, et al. Chopper system for time resolved experiments with synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2009;80:015101. doi: 10.1063/1.3036983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Sinning I, Michel H. Crystallographic refinement at 2.3 Å resolution and refined model of the photosynthetic reaction centre from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:429–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan Y, et al. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ceccarelli M, Procacci P, Marchi M. An ab initio force field for the cofactors of bacterial photosynthesis. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:129–142. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Autenrieth F, Tajkorsid E, Baudry J, Luthey-Schulten Z. Classical force field parameters for the heme prosthetic group of cytochrome c. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1613–1622. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gast P, Hemelrijk P, Hoff AJ. Determination of the number of detergent molecules associated with the reaction center protein isolated from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis. Effects of the amphiphilic molecule 1,2,3-heptanetriol. FEBS Lett. 1994;337:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Van Gunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. Molecular-dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comp. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essmann U, et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess B, Kutzner C, Van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theo. Comp. 2007;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breton J, Martin JL, Migus A, Antonetti A, Orszag A. Femtosecond spectroscopy of excitation energy transfer and initial charge separation in the reaction center of the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:5121–5125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.