An ascorbate peroxidase functions to protect maturing and early germinating seeds from stress and modulate the seed’s cellular metabolism and signaling.

Abstract

A seed’s ability to properly germinate largely depends on its oxidative poise. The level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) is controlled by a large gene network, which includes the gene coding for the hydrogen peroxide-scavenging enzyme, cytosolic ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE6 (APX6), yet its specific function has remained unknown. In this study, we show that seeds lacking APX6 accumulate higher levels of ROS, exhibit increased oxidative damage, and display reduced germination on soil under control conditions and that these effects are further exacerbated under osmotic, salt, or heat stress. In addition, ripening APX6-deficient seeds exposed to heat stress displayed reduced germination vigor. This, together with the increased abundance of APX6 during late stages of maturation, indicates that APX6 activity is critical for the maturation-drying phase. Metabolic profiling revealed an altered activity of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, changes in amino acid levels, and elevated metabolism of abscisic acid (ABA) and auxin in drying apx6 mutant seeds. Further germination assays showed an impaired response of the apx6 mutants to ABA and to indole-3-acetic acid. Relative suppression of abscisic acid insensitive3 (ABI3) and ABI5 expression, two of the major ABA signaling downstream components controlling dormancy, suggested that an alternative signaling route inhibiting germination was activated. Thus, our study uncovered a new role for APX6, in protecting mature desiccating and germinating seeds from excessive oxidative damage, and suggested that APX6 modulate the ROS signal cross talk with hormone signals to properly execute the germination program in Arabidopsis.

Seed development and seed germination are two critical phases in the plant life cycle. Dehydration and rehydration during seed development or during germination are associated with high levels of oxidative stress (Dandoy et al., 1987; Rajjou et al., 2012). Overaccumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause oxidative damage to a wide range of cellular components and cause DNA damage, reducing the seed’s ability to germinate (Bailly et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2011; Parkhey et al., 2012). An optimal range of ROS levels is required for successful germination (Bailly et al., 2008). Below this, germination is suppressed (e.g. in dormant seeds), and above it, cellular oxidative damage accumulates, delaying or inhibiting germination. This concept, termed the oxidative window of germination, demonstrates the duality of ROS in seed physiology (Bailly et al., 2008). Experiments in rice (Oryza sativa), grasses, and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), in which suppression of ROS production inhibited germination, demonstrate the requirement of ROS for germination (Sarath et al., 2007; Leymarie et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012). It was further suggested that ROS accumulation during a period of dry storage following harvest, so called after-ripening, acts as a key signal in changing proteome oxidation to prepare the embryo for germination (Job et al., 2005; Oracz et al., 2009). Arabidopsis nondormant seeds, in which dormancy was alleviated by after-ripening or light treatment, produced more ROS than dormant seeds during imbibition (Leymarie et al., 2012).

The commitment of seeds to germination is determined during the seeds’ maturation on the mother plant, with desiccation, accumulation of storage proteins, and transcription of genes that are translated during imbibition (Rajjou et al., 2004, 2012; Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006; Finkelstein et al., 2008; Holdsworth et al., 2008). Therefore, the potential of seeds for rapid uniform emergence and development under a wide range of field conditions (i.e. seed vigor) greatly depends on the proper execution of seed maturation- and desiccation-related processes (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006).

ROS also play a key regulatory role in the germination program under favorable conditions (Sarath et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Bahin et al., 2011; Ye and Zhang, 2012). Germination begins with the release of dormancy, which is controlled by abscisic acid (ABA) and the activation of GA, which control germination-promoting signals (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006; Finkelstein et al., 2008).

Recent studies in Arabidopsis and barley (Hordeum vulgare) have shown that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) mediates the regulation of ABA catabolism, antagonizes ABA signaling, and promotes GA synthesis and its germination program (Liu et al., 2010; Bahin et al., 2011; Ishibashi et al., 2012; Krishnamurthy and Rathinasabapathi, 2013). Furthermore, dormancy release, in both dry and imbibed states, has been associated with ROS production and the specific oxidation of embryonic proteins, of fatty acids, and of mRNA molecules (Job et al., 2005; Oracz et al., 2007, 2009; Bazin et al., 2011). Protein carbonylation, the most prevalent type of protein oxidation caused by ROS, has been shown to target a specific set of embryo proteins and was suggested to be part of the dormancy alleviation mechanism in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and Arabidopsis seeds (Job et al., 2005; Oracz et al., 2007, 2009). Recent studies also support interactions between ROS, ethylene, cytokinin, and auxin in controlling seed germination and early seedling development (Oracz et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Subbiah and Reddy, 2010; He et al., 2012; Krishnamurthy and Rathinasabapathi, 2013; Lin et al., 2013). All of these accumulated findings indicate that ROS signals play key roles in seed development and germination and demonstrate the diversity and complexity of ROS function.

Because ROS metabolism and signaling are central in dormancy and germination control, a tight regulation is required to properly execute these programs while avoiding oxidative stress. In Arabidopsis, there are over 150 enzymes dedicated to reducing ROS types, such as H2O2, superoxide ions, and others, to their lesser reactive forms (Mittler et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008, 2010). Ascorbate peroxidases (APXs) comprise a small family of nine enzymes in Arabidopsis that use ascorbic acid (AA) as a substrate to reduce H2O2 to water (Mittler et al., 2004; The Arabidopsis Information Resource 10). Of the three cytosolic ascorbate peroxidases (cAPXs), the functions of APX1 and APX2 are relatively well established (Panchuk et al., 2002; Davletova et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2013a). APX1 is the most abundant APX, which functions in protecting cellular components, including chloroplasts, from oxidative damage as well as modifying cellular and intracellular ROS signals (Davletova et al., 2005; Vanderauwera et al., 2011; Suzuki et al., 2013b). In contrast, the APX2 expression level is constitutively very low under normal conditions but is highly induced in response to high temperatures and increased light intensity (Panchuk et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2013a). However, very little is known about the expression of the third cAPX, APX6, and its function is practically unknown. In this work, we identified the function of APX6 in seeds using two independent Arabidopsis knockout lines. Here, we show that APX6 is important for protecting mature desiccating seeds as well as germinating seeds from excessive oxidative stress and also functions in maintaining seed vigor under stress conditions. In addition, we discovered a novel interplay between ROS and ABA and between ROS and auxin that could be interdependent.

RESULTS

Germination Phenotype of APX6-Deficient Mutants under Favorable and Stress Conditions

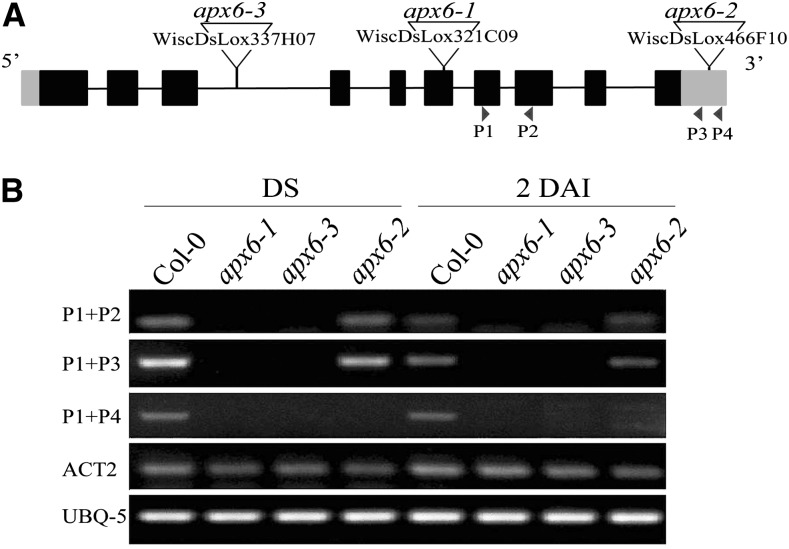

To study the role of APX6 in Arabidopsis, three independent transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion lines were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Fig. 1A). Phenotypic evaluation of the identified homozygous lines indicated relatively slower and poorer germination rates on soil as compared with the wild type. The germination phenotype of apx6-1 and apx6-3 was consistent, and these lines were later shown in reverse transcription-PCR to be true knockout lines (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the 3′ untranslated region insertion line apx6-2 showed an inconsistent germination phenotype and showed APX6 expression similar to the wild type (Fig. 1B). Therefore, only the apx6-1 and apx6-3 lines were further characterized.

Figure 1.

Gene structure and expression of APX6 in seeds. A, Gene map of the APX6 gene model. Exons are represented by boxes (untranslated regions in gray and coding sequence in black) and introns by the black line. The T-DNA insertions into the gene are shown as triangles. Arrowheads below represent primers (P1–P4) used for absence verification of the APX6 transcript expression in B. B, Semiquantitative PCR in dry seeds (DS) and in germinating seeds at 2 DAI. Col-0, Columbia-0.

Following germination, under favorable conditions, the seedlings and mature knockout plants were comparable to wild-type plants, exhibiting similar growth rates and mature plant sizes (Supplemental Fig. S1).

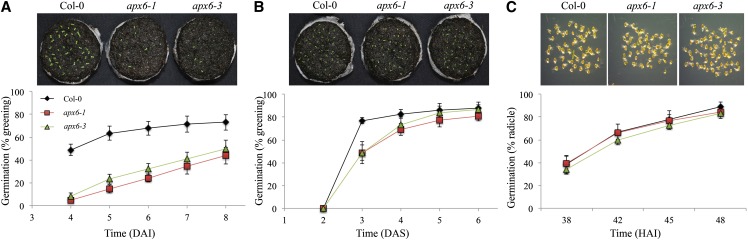

Germination of freshly harvested nonstratified apx6-1 and apx6-3 seeds on soil pellets resulted in a dramatic delay and reduced level of germination, measured as the appearance of cotyledons (Fig. 2A). Four days after imbibition (DAI), only approximately 5% of the mutants were germinated, compared with 50% of the wild type. The germination rate of apx6 mutants continued steadily and slowly, reaching less than 45% germination at 8 DAI (Fig. 2A). Stratification treatment (48 h at 4°C) dramatically improved the germination rate, although it did not completely reverse it (Fig. 2B). At 5 and 6 DAI, germination was 63% and 85% relative to the wild type, respectively (P < 5 × 10−6 and P < 0.01, respectively). In contrast, germination on plant growth medium (0.5× Murashige and Skoog [MS] medium and 0.8% agar) did not result in apparent differences in the rate of germination (radicle emergence) between the wild type and apx6 mutants (Fig. 2C). This delayed-germination phenotype on soil and the lack of it on MS medium was consistent.

Figure 2.

Germination phenotype of apx6 mutants under favorable conditions. A and B, Germination rates of freshly harvested seeds on soil pellets (A) and following stratification treatment at 4°C for 48 h (B). The images above were taken 6 DAI and 4 d after stratification (DAS) as indicated. The germination rate was scored as cotyledon emergence. C, Germination rate on 0.5× MS agar. Germination was scored as radicle emergence. The images above were taken at 48 HAI. sd values represent averages of eight replicates of 50 seeds. Col-0, Columbia-0. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

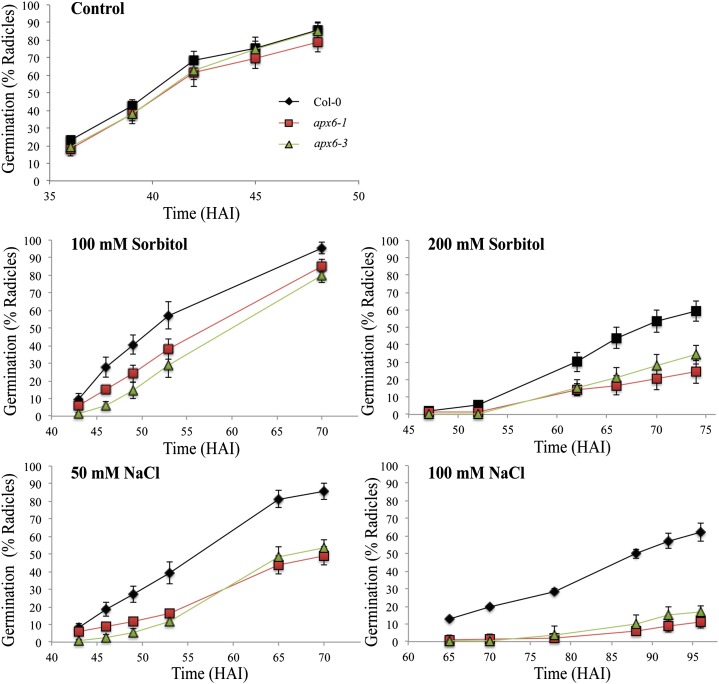

Soil pellets are relatively hyperosmotic compared with MS media and the high-humidity environment inside the plates. This and the results in Figure 2 pointed us to the possibility that APX6’s function might be in protecting germinating seeds under low water potentials. To test this hypothesis, we germinated the wild type and apx6 mutants on MS medium supplemented with sorbitol (100 and 200 mm) and NaCl (50 and 100 mm; Fig. 3). Both apx6 lines showed severe inhibition of germination in both treatments compared with the wild type. These results clearly suggest that APX6 protects germinating seeds from oxidative stress impediments that accompany osmotic stress.

Figure 3.

Germination assays of freshly harvested seeds under hyperosmotic conditions: 0.5× MS medium supplemented with NaCl or sorbitol. sd values represent averages of eight replicates of 50 seeds. Col-0, Columbia-0. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

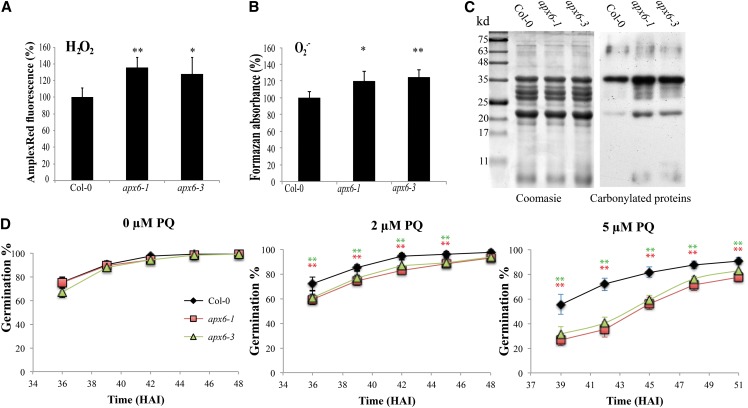

We then evaluated the antioxidative impact of APX6 in seeds by comparing ROS levels and oxidative damage accumulated in the dry seeds of apx6 and the wild type (Fig. 4). The levels of H2O2 and superoxide radicals measured in dry seed extracts were 28% to 35% and 20% to 25% higher, respectively, in both apx6 lines compared with the wild type (Fig. 4, A and B). In addition, the higher levels of ROS in the mutants were correlated with oxidative damage, as demonstrated by increased accumulation of carbonylated proteins (Fig. 4C). A general peroxidase activity assay showed reduced activity in dry seeds of apx6-1 (Supplemental Fig. S2), which is in agreement with the elevated level of H2O2 and increased oxidative damage. We further measured AA and total glutathione in dry seeds of the wild type and apx6-1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). The level of total glutathione accumulated in wild-type seeds was approximately 25% higher on average compared with apx6-1. The level of AA in apx6-1 was 5% lower and the level of dehydroascorbate (oxidized AA; DHA) was 25% higher on average compared with the wild type, although these differences were not significant. However, the ratio of reduced to oxidized AA was significantly higher in the wild type (P < 0.05, Student’s t test). Seeds of apx6 mutants were further tested for germination under oxidative stress on MS agar containing elevated concentrations of the superoxide-generating agent Paraquat. The apx6 lines showed increased sensitivity, as demonstrated by the dose-response-delayed germination of the mutant relative to the wild type (Fig. 4D), indicating that the apx6 lines are more sensitive to oxidative stress. Taken together, the results presented in Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure S3 suggested that there is a higher oxidative level in dry apx6 than in the wild type.

Figure 4.

ROS levels in dry seeds and germination response to oxidative stress. A, Relative levels of H2O2, normalized to the wild-type level, were measured using the Amplex Red fluorescence assay. B, Relative levels of superoxide radicals (O2∙−) were measured as formazan accumulation in nitroblue tetrazolium staining. C, Protein oxidation assay, showing carbonylated proteins (right) on a western blot of 10 µg of total seeds and Coomassie Blue staining (left) as a loading control. D, Germination assay was conducted on 0.5× MS medium containing Paraquat (PQ). sd values for all samples represent averages of eight replicates of 50 seeds. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test significance at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Col-0, Columbia-0. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

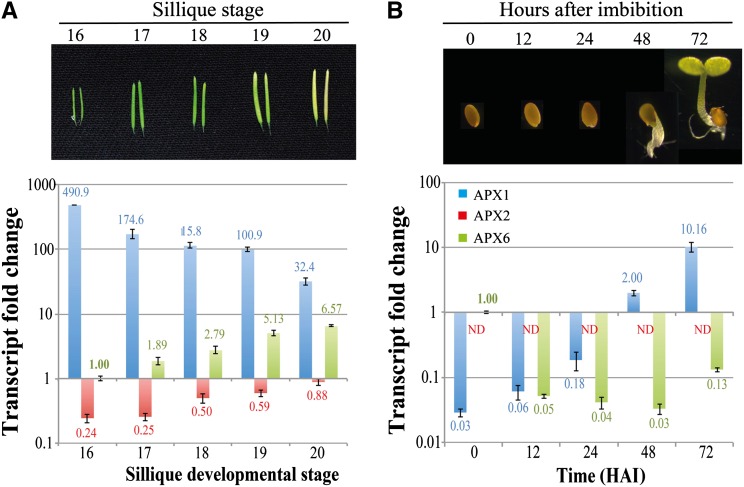

Expression Profile of cAPXs in Maturing and Germinating Seeds

A large degree of redundancy is assumed for the ROS-gene network; however, some degree of specialization is expected (Mittler et al., 2004). This redundancy explains why the inhibition of germination in both the wild type and apx6 mutants was not acute. A Genevestigator developmental expression graph of all nine Arabidopsis APXs revealed that, in seeds, only APX6 shows an increase while the levels of all others decrease or remain unchanged (https://www.genevestigator.com/gv/; Zimmermann et al., 2004; Supplemental Fig. S4). This could lend support for a specific role of APX6 in seeds. An Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph browser developmental heat map in developing seeds further shows that APX6 is uniformly abundant in all the seed’s tissues (Supplemental Fig. S5; http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi; Winter et al., 2007). The Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph browser profile of germinating seeds has revealed that the level of APX6 decreased sharply already within 3 h after imbibition (HAI; Winter et al., 2007). To learn more about the expression of APX6 and the division of labor among the three cAPXs, we determined their wild-type steady-state transcriptional levels in late maturing siliques (stages 16–20; i.e. in mature desiccating seeds) as well as in germinating seeds (0–72 HAI; Fig. 5). Real-time PCR analysis uncovered reciprocal trends in the expression of APX1 and APX6; while the abundance of APX1 declined as seeds matured and desiccated, the APX6 mRNA level slowly accumulated (Fig. 5A), and the opposite occurred during germination (Fig. 5B). The maximal abundance of APX6 was detected in mature dry seeds, which was about 30-fold higher than the level of APX1 (Fig. 5B). APX6 transcript levels decreased sharply, almost 20-fold, within 12 HAI, while the APX1 level slowly increased, reaching a comparable but relatively low level (Fig. 5B). The low levels of the three cAPXs persisted until germination was completed with the emergence of the radicle at 48 HAI. Following germination, the level of APX1 increased sharply, becoming once again the dominant cAPX. The APX2 level also increased during seed maturation; however, it still remained much lower compared with APX1 and APX6 and was undetectable throughout germination (Fig. 5). Taken together, the gradual replacement of APX1 with APX6 in desiccating seeds and contrariwise in germinating seeds indicates specialization and tight control over the expression of cAPXs.

Figure 5.

Developmental expression pattern of cAPXs in the wild type. Relative expression of APX1, APX2, and APX6 was determined by real-time PCR analyses during the final stages of silique development (seed maturation; A) and seed germination (B). The fold change values, presented above and below the bars, are normalized to the APX6 level in stage 16 siliques (in A) or to the APX6 level in mature dry seeds (0 HAI; in B). sd values represent averages of three replicates for each stage. ND, Not determined.

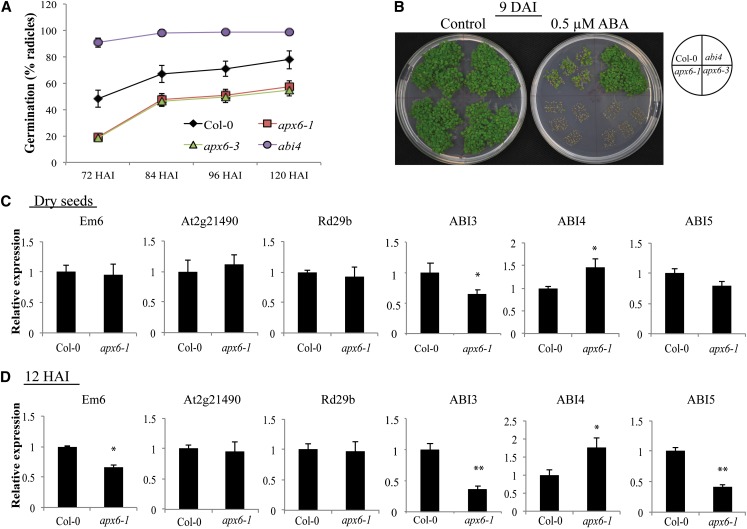

ABA Response and Metabolic Profiling in Seeds

The reversal of germination of apx6 seeds by stratification treatment (Fig. 2B) strongly pointed to the involvement of ABA. Cross talk between ABA and ROS was previously shown in several independent studies (Sarath et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Bahin et al., 2011; Ishibashi et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2012; Lariguet et al., 2013). To further investigate the possible relationship between APX6 activity in seeds and ABA, freshly harvested seeds of the wild type, apx6, and abi4 as a positive control were germinated on MS medium containing 0.5 µm ABA (Fig. 6, A and B). ABA strongly inhibited the germination of apx6-1 and apx6-3 compared with the germination rate of wild-type and abi4 seeds. Five DAI, only 54% of apx6 seeds showed emerged radicles (Fig. 6A), with only minor progression within the following 4 d (Fig. 6B). Stratification treatment partially alleviated the inhibition of ABA on the germination of apx6, resulting in a uniform and complete germination within 7 d after stratification. Yet, apx6 germination and the development of the seedlings were still retarded compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S6). These results suggest that APX6 is involved in the release of the ABA inhibitory effect during germination and perhaps also during early stages of seedling development.

Figure 6.

Response of apx6 mutants to ABA. A and B, Germination assay on 0.5× MS medium containing 0.5 µm ABA (A) and a representative image showing germination at 9 DAI (B). sd values represent averages of eight replicates. C and D, Relative transcript levels of ABA-responsive and signaling genes in dry seeds (C) and at 12 HAI (D). sd values represent averages of three replicates. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test significance at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Col-0, Columbia-0. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Next, we examined whether differences in the expression of ABA-related genes in dry and imbibed seeds could account for the hypersensitivity to ABA (Fig. 6, C and D). We examined the expression of the ABA signal transduction genes ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 and the expression of the ABA response marker genes EARLY METHIONINE-LABELLED6 (EM6) and RESPONSIVE TO DESSICATION 29B (Rd29b) and dehydrin Late Embryogenesis Protein (LEA) (At2g21490). Apart from a slightly reduced EM6 level in apx6-1 imbibed seeds, no significant changes were detected in ABA response marker genes between apx6-1 and the wild type (Fig. 6, C and D). In contrast, the transcript levels of ABI3 and ABI5 showed mild suppression in dry seeds (a decrease of 22% and 35% relative to the wild type, respectively) that was further increased during imbibition (2.7- and 2.4-fold decrease relative to the wild type, respectively). Conversely, ABI4 levels increased 45% and 75% relative to the wild type in dry and imbibed seeds, respectively (Fig. 6, C and D).

Next, we performed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses to measure the levels of ABA, its metabolic intermediates, as well as other phytohormones that may be involved in regulation of the germination phenotype of apx6 (Table I). The ABA level in apx6-1 was 40% higher than in the wild type. Furthermore, the levels of inactivated forms of ABA were higher in the mutant, particularly dihydrophaseic acid, which was more than 5-fold higher (P < 0.0001, Student’s t test). These findings suggest that apx6 seeds have a higher level of ABA metabolism during maturation compared with the wild type.

Table I. Levels of phytohormones in dry seeds.

Values are means ± sd (pmol g−1 fresh weight) and ratios as indicated. sd values represents five replicates. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test significance at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

| Group | Compound | Feature | Wild Type | apx6-1 | Ratio, apx6-1:Wild Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAs | ABA | Active | 335.62 ± 83.82 | 483.59 ± 136.17 | 1.44 |

| PA | Deactivated | 2.38 ± 1.03 | 3.65 ± 1.16 | 1.53 | |

| Dihydrophaseic acid | Deactivated | 4.50 ± 0.87 | 23.10 ± 4.98** | 5.14 | |

| 9OH-ABA | Deactivated | 0.37 ± 0.29 | 0.86 ± 0.64 | 2.32 | |

| Auxins | IAA | Active | 330.80 ± 78.02 | 636.68 ± 174.61* | 1.92 |

| IPA | Precursor | 55.28 ± 11.07 | 67.67 ± 19.78 | 1.22 | |

| IAM | Precursor | 1.6 ± 1.40 | 8.22 ± 6.20 | 5.64 | |

| IAN | Precursor | 1,919.9 ± 1,122.84 | 1,028.79 ± 184.31 | 0.54 | |

| IAA-Asp | Degradation | 557.29 ± 248.39 | 1,233.18 ± 692.24 | 2.21 | |

| IAA-Glu | Degradation | 2.96 ± 1.69 | 33.58 ± 23.79* | 11.34 | |

| OxIAA | Degradation | 8,193 ± 2,090 | 12,100.48 ± 2,777.42 | 1.48 | |

| OxIAA-GE | Degradation | 257 ± 94 | 436.12 ± 179.87 | 1.70 | |

| GA4 | Active | 55.50 ± 17 | 99.14 ± 27.73* | 1.79 | |

| GAs | GA19 | Precursor | 29.36 ± 20 | 27.79 ± 22.34 | 0.95 |

| Cytokinins | tZ | Active | 1.53 ± 0.62 | 2.23 ± 0.36 | 1.46 |

| tZR | Active | 4.13 ± 1.06 | 4.54 ± 1.10 | 1.10 | |

| DZR | Active | 0.56 ± 0.20 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 0.71 | |

| iP | Active | 0.22 ± 0.16 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.37 | |

| iPR | Active | 0.97 ± 0.32 | 0.90 ± 0.25 | 0.92 | |

| cZ | Active | 0.75 ± 0.30 | 1.73 ± 0.81 | 2.31 | |

| cZR | Active | 5.07 ± 1.76 | 6.80 ± 1.41 | 1.34 | |

| tZ7G | Deactivated | 2.26 ± 0.43 | 2.52 ± 0.75 | 1.11 | |

| tZ9G | Deactivated | 0.43 ± 0.14 | 1.00 ± 0.32* | 2.32 | |

| DZ9G | Deactivated | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.87 | |

| iP7G | Deactivated | 49.36 ± 12.25 | 64.96 ± 9.94 | 1.32 | |

| iP9G | Deactivated | 0.46 ± 0.24 | 1.06 ± 0.38* | 2.29 | |

| cZ7G | Deactivated | 6.46 ± 0.98 | 11.17 ± 3.11* | 1.74 | |

| tZRMP | Precursor | 1.43 ± 0.39 | 1.24 ± 0.29 | 0.87 | |

| iPRMP | Precursor | 0.99 ± 0.27 | 1.28 ± 0.11 | 1.29 | |

| tZOG | Storage | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 0.72 | |

| tZROG | Storage | 2.19 ± 0.87 | 2.08 ± 0.86 | 0.95 | |

| DZROG | Storage | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 1.20 | |

| cZOG | Storage | 0.56 ± 0.34 | 0.66 ± 0.31 | 1.19 | |

| cZROG | Storage | 0.42 ± 0.22 | 1.57 ± 1.11 | 3.79 |

Furthermore, the level of the active GA4 was 79% higher (P < 0.005) in the mutant, while the level of GA19, the precursor of GA1, was similar in both seed types. Some effects on cytokinin metabolism were detected, as differences were found in active and storage forms of cytokinins and several inactive forms. However, no clear trend was observed. Interestingly, the most striking finding was the changes observed in auxin homeostasis. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) level in apx6 seeds was almost twice that found in the wild type (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the level of IAA-Glu, the auxin degradation by-product, was 11 times higher in the mutant (P < 0.005). Taken together, these metabolic changes suggest that APX6 may play an important role in regulating major hormone metabolic pathways in desiccating seeds.

To gain a better understanding of the effect of APX6 on metabolic processes in seeds, we performed a comparative nontargeted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis for several primary metabolites (Table II), including analysis for amino acids (Table III). Principal component analysis comparison of all metabolites included in Tables II and III showed divergent distribution for apx6-1 and wild-type samples, demonstrating the dissimilarities between them (Supplemental Fig. S7). The most notable changes in the primary metabolites appeared in the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, succinate, citrate, fumarate, and malate, which were all significantly elevated in apx6-1 (Table II). These results suggest that desiccating apx6 seeds had an altered tricarboxylic acid cycle activity during development and that an increased respiration rate might exist. In contrast, very little or no significant changes in the levels of sugars and polyols were observed.

Table II. Levels of primary metabolites in dry seeds.

Values are means ± sd (peak area per 1,000) and ratios as indicated. sd values represent five replicates. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test significance at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 5 × 10−4.

| Group | Compound | Wild Type | apx6-1 | Ratio, apx6-1:Wild Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugars | Fru monophosphate | 2,725 ± 871 | 3,633 ± 1,679 | 1.3 |

| Gluconic acid | 872 ± 168 | 1,362 ± 489* | 1.6 | |

| Glc biphosphate | 3,629 | 5,050 ± 1,155 | 1.4 | |

| Glc monophosphate | 25,475 ± 9,644 | 34,960 ± 6,984 | 1.4 | |

| Suc | 111,163 ± 13,640 | 144,169 ± 33,243 | 1.3 | |

| Polyols | Erythritol | 494 ± 129 | 634 ± 82* | 1.3 |

| Glycerol | 4,114 ± 402 | 4,847 ± 622 | 1.2 | |

| Myoinositol | 11,692 ± 691 | 11,003 ± 2,911 | 0.9 | |

| Sorbitol | 1,789 ± 748 | 2,259 ± 1,386 | 1.3 | |

| Xylitol | 161 ± 16 | 150 ± 39 | 0.9 | |

| Organic acids | Citrate | 4,727 ± 839 | 10,510 ± 2,214**** | 2.2 |

| Fumarate | 1,568 ± 322 | 8,963 ± 2,432**** | 5.7 | |

| Malate | 2,294 ± 321 | 6,071 ± 1,625**** | 2.6 | |

| Succinate | 337 ± 54 | 471 ± 83** | 1.4 | |

| Benzoate | 3,245 ± 346 | 4,801 ± 489**** | 1.5 | |

| Nicotinic acid | 1,687 ± 148 | 3,177 ± 327**** | 1.9 | |

| Palmitate | 2,765 ± 1,005 | 3,895 ± 2,220 | 1.4 | |

| Pyro-Glu | 31,141 ± 8,245 | 55,645 ± 16,678** | 1.8 | |

| Miscellaneous organic acid | Ethanolamine | 10,923 ± 4,439 | 9,078 ± 2,216 | 0.8 |

| Inorganic acids | Phosphoric acid | 1,066 ± 203 | 2203 ± 830** | 2.1 |

| Hydroxylamine | 5,345 ± 528 | 7,277 ± 1,739* | 1.4 |

Table III. Levels of amino acids in dry seeds.

Values are means ± sd (nmol g−1 fresh weight) and ratios as indicated. sd values represent five replicates. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test significance at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 5 × 10−3, and ****P < 5 × 10−4.

| Amino Acid | Wild Type | apx6-1 | Ratio, apx6-1:Wild Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | 158.26 ± 18.59 | 217.08 ± 2.59**** | 1.37 |

| Asn | 134.57 ± 58.47 | 290.98 ± 86.70** | 2.16 |

| Asp | 127.64 ± 26.59 | 403.31 ± 126.01**** | 3.16 |

| Cys | 3.39 ± 1.34 | 3.84 ± 0.69 | 1.13 |

| Glu | 776.44 ± 136.10 | 1,149.97 ± 211.60*** | 1.48 |

| Gln | 35.31 ± 8.01 | 68.33 ± 18.73*** | 1.94 |

| Gly | 233.84 ± 129.56 | 255.62 ± 174.45 | 1.09 |

| His | 2.55 ± 0.93 | 4.36 ± 1.13* | 1.71 |

| Homoserine | 12.90 ± 3.60 | 15.90 ± 2.87 | 1.23 |

| Ile | 110.16 ± 17.65 | 174.54 ± 24.64**** | 1.58 |

| Leu | 86.06 ± 14.30 | 139.16 ± 19.71**** | 1.62 |

| Lys | 5.80 ± 1.00 | 10.47 ± 3.41** | 1.80 |

| Met | 46.33 ± 14.27 | 52.08 ± 8.75 | 1.12 |

| Phe | 158.19 ± 45.92 | 240.10 ± 36.42** | 1.52 |

| Pro | 83.76 ± 21.09 | 237.77 ± 17.94**** | 2.84 |

| Ser | 175.02 ± 15.83 | 280.70 ± 66.30*** | 1.60 |

| Thr | 96.65 ± 9.51 | 146.62 ± 37.41** | 1.52 |

| Trp | 480.54 ± 77.42 | 177.25 ± 31.61**** | 0.37 |

| Tyr | 54.50 ± 7.30 | 65.75 ± 14.40 | 1.21 |

| Val | 245.46 ± 38.87 | 411.542 ± 65.52**** | 1.68 |

The levels of most amino acids were significantly elevated in the mutant. Among the highly accumulated amino acids (more than 2-fold) were Asn, Asp, and Pro (Table III). Asp is produced from Glu and oxaloacetate, which is also the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediate linking malate and citrate. This finding further corresponds with the accumulation in tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolites (Table II) and suggests that the oxaloacetate production rate is elevated in apx6 seeds. Pro functions as a compatible solute that is well known to accumulate during drought and salt stress to counteract the reduction in osmotic potential (Lehmann et al., 2010). The levels of Leu, Ile, and Val, collectively known as coordinately regulated branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), similarly increased by 60% to 70% in apx6 seeds. Like Pro, the three BCAAs are known to be involved in protection during abiotic stresses, particularly osmotic stress (Joshi et al., 2010). In contrast, Trp is the only amino acid depleted in apx6 seeds, showing a 2.7-fold decrease compared with the wild type (Table I). This reduction is inversely correlated with the accumulation of auxins, which is logical, since Trp is the precursor for auxin biosynthesis.

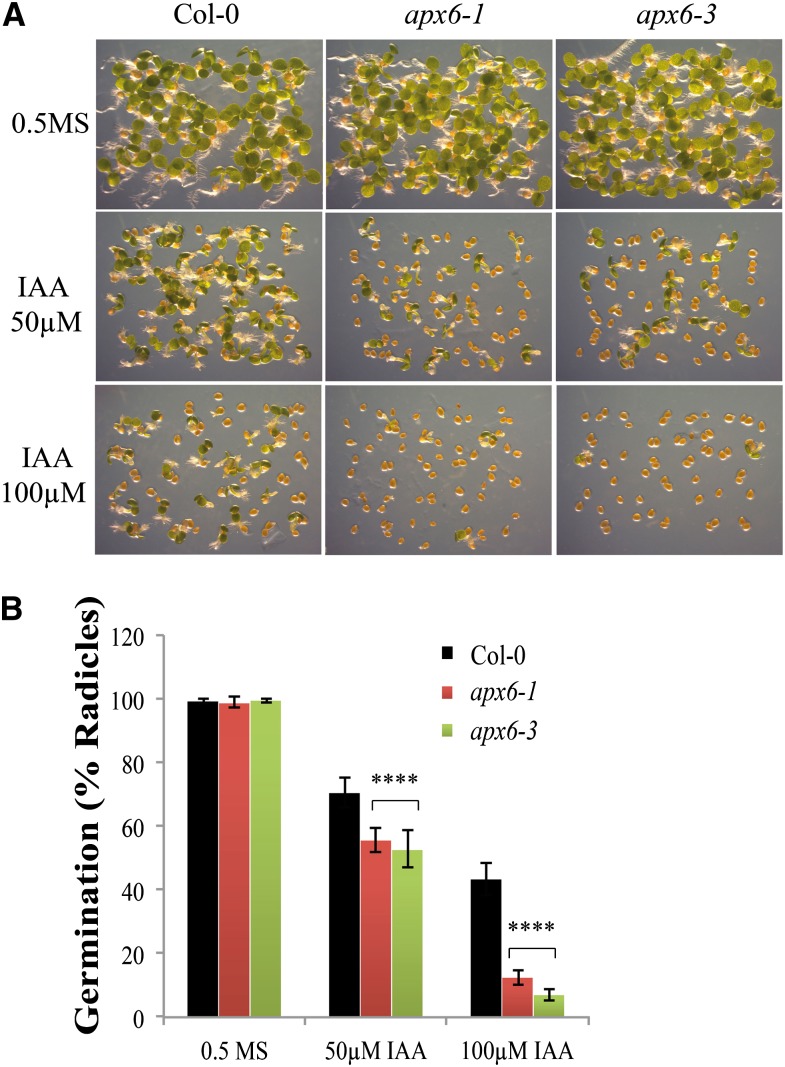

Auxin was most recently shown to promote seed dormancy through the stimulation of ABA signaling (Liu et al., 2013). Our results in the apx6 mutant point to a possible link between IAA and ABA through H2O2. To test the possibility that IAA is involved in the reduced-germination phenotype of apx6 mutants, seeds were germinated on plant medium containing IAA. Both mutant lines showed clear inhibition at 50 µm and an almost complete suppression at 100 µm (P < 0.001; Fig. 7). This result suggests that there is interplay between IAA and H2O2 in the ABA-mediated dormancy that is regulated by APX6 in seeds.

Figure 7.

Response of apx6 mutants to auxin. Freshly harvested seeds were germinated on 0.5× MS medium with IAA. Sample images of seed germination (A) and histograms of germination at 5 DAI (B) are shown. sd values represent averages of eight replicates of 50 seeds. ****Student’s t test significance at P < 5 × 10−4. Col-0, Columbia-0. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

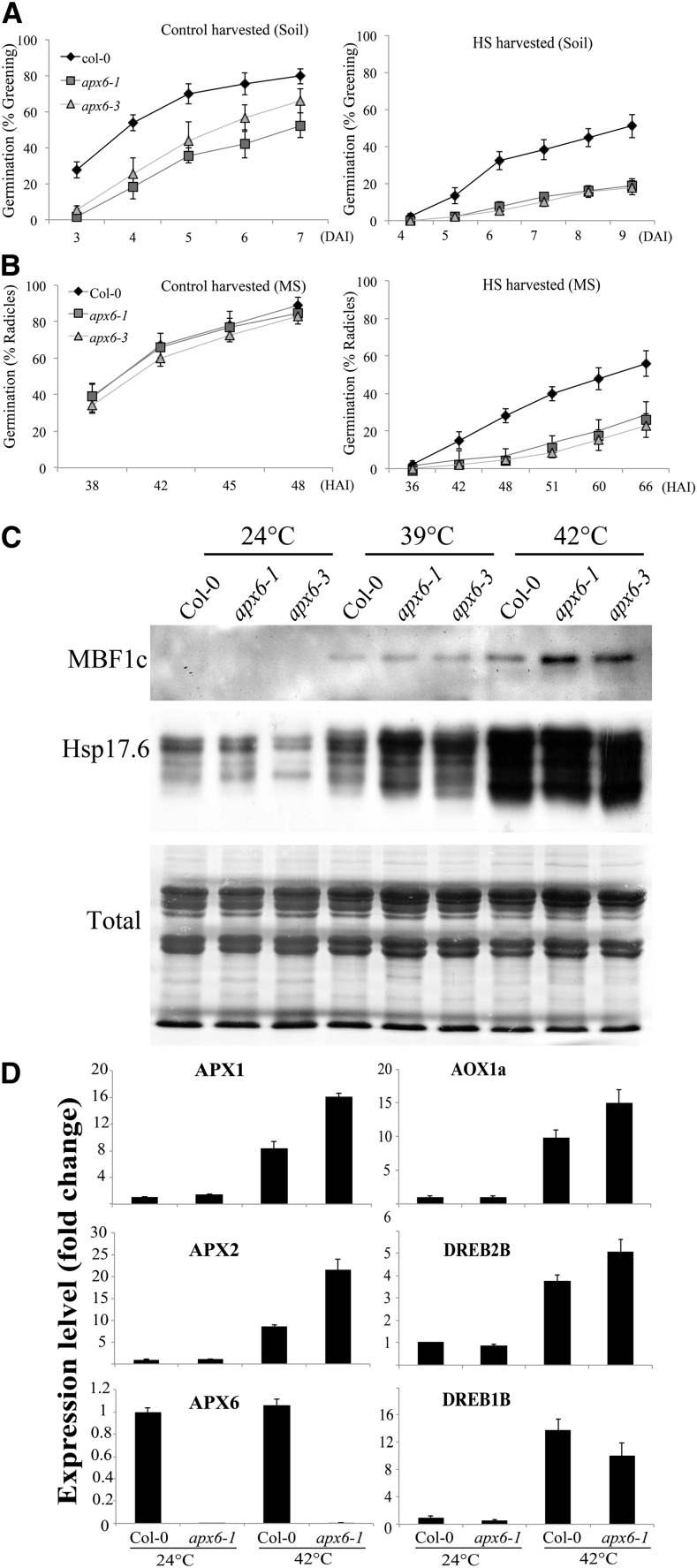

Response and Tolerance of Seeds to Heat Stress Conditions

Desiccation (i.e. drought stress) and heat stress (HS) are two conflicting stresses, which are more harmful when combined (Rizhsky et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 2014). To test whether desiccating apx6 seeds are more sensitive to HS, we exposed 45-d-old flowering plants bearing siliques (stages 17 and 18) to HS. Plants were subjected to a daily regime of climbing temperatures, starting at 24°C and peaking at 39°C or 42°C at midday. The dry seeds were collected after 5 and 6 d.

The impact of the 42°C HS on seed vigor was tested by germination assays of freshly harvested stressed seeds on either soil pellets or MS agar under controlled conditions (Fig. 8, A and B). In both assays, apx6 seeds showed dramatic retardation in germination compared with wild-type seeds (Fig. 8, A and B). Western-blot analysis of dry seeds collected from 39°C- or 42°C-stressed plants revealed higher accumulation of the HS-responsive proteins multiprotein bridging factor 1C (MBF1c) and heat shock proteins in apx6 seeds (Fig. 8C). In addition, APX1 and APX2 transcripts increased 2- and 2.5-fold, respectively, in apx6 seeds collected at 42°C (Fig. 8D). The higher accumulation of both HS-responsive APX1 and APX2 indicates the activation of a compensatory mechanism to protect apx6 seeds from HS-associated oxidative stress, which most likely prevents greater oxidative damage.

Figure 8.

Effect of heat stress on mature drying seeds. A and B, Germination assay on soil pellets (A) and on 0.5× MS medium (B) of seeds harvested from plants grown under favorable conditions at 24°C and seeds harvested from plants exposed to HS (42°C) for the last 5 to 6 d of their maturation (see “Materials and Methods”). sd values represent averages of eight replicates of 50 seeds. C, Western blots showing HS-responsive proteins, MBF1c and Hsp17.6, in dry seeds that experienced HS (39°C and 42°C) prior to harvesting (during maturation on the mother plant). D, Relative transcript abundance of the three cAPXs and other stress-responsive genes in the 42°C-stressed dry seeds. sd values represent averages of three replicates. Col-0, Columbia-0.

We next tested whether mature apx6 seeds are also more sensitive to HS during germination. For this purpose, seeds of the wild type and apx6-1 collected under control conditions (i.e. 24°C) were exposed to 42°C for 6, 12, 24, or 42 h. Following the HS period, the seeds were transferred to 24°C for recovery and germination completion. The results revealed that the longer the stress period persisted, the greater was the impairment in the germination of apx6 compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S8). Since APX6 expression declines sharply within a few hours after imbibition (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S5B), these findings suggest that APX6 activity is required for seed thermotolerance during the initial stage of germination and further suggest that this stage is most vulnerable to stress. Taken together, these results further support the function of APX6 as an important antioxidative mechanism that protects seeds from abiotic pressures during maturation and germination.

DISCUSSION

In this study, new varied roles were identified for cytosolic APX6 in Arabidopsis seeds during maturation and germination. We have shown that APX6 is a major component of the antioxidative mechanism that is important for seed vigor under favorable conditions and even more so during stress.

The expression pattern of APX6 (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S5), together with the germination phenotypes of the mutants, highlight the specialized function of APX6 during seed desiccation and during the early stage of germination. The function of APX6 seems to be critical during the maturation-drying phase, in which the metabolism of the seed shifts from a general decrease in unbound metabolites to the accumulation of a set of specific metabolites (Angelovici et al., 2010). In addition, the stored reservoir of APX6 in the dry seed would serve in protecting the embryo from excessive oxidative pressure that accompanies the increased respiratory metabolism during imbibition. Furthermore, APX6 is required to protect seeds against osmotic stress (Fig. 3), and in its absence increased accumulation of Pro and BCAAs, which function in osmotolerance (Joshi et al., 2010; Lehmann et al., 2010), may provide partial compensation.

Multiple types of stress cause fluctuations in energy that ultimately converge and generate energy deficiency signals, resulting in energy sensor activation (Baena-González and Sheen, 2008). This could be the case for apx6 seeds undergoing maturation drying under favorable conditions and even more so during HS, which further increases respiration rate, as indicated by the elevated expression of the ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE 1a AOX1a) gene (Fig. 8D). Indeed, increased activation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, as indicated by the accumulation of its intermediates (Table II), could increase energy generation (Angelovici et al., 2011; Galili, 2011) to compensate for energetic depletion in the absence of APX6.

The relative elevation of most amino acids could potentially be attributed, at least in part, to an increase in the degradation of oxidized proteins (Fig. 4D), since carbonylated proteins are destined for degradation (El-Maarouf-Bouteau et al., 2013). Positive feedback for tricarboxylic acid cycle activity was recently shown due to the contribution of catabolism of the Asp family pathway amino acids, Lys, Met, Thr, Ile, and Gly (Galili, 2011). Activation of such positive feedback in apx6 seeds might explain the fact that the level of Asp family amino acids showed little or no increase compared with the wild type, while the Asp level was 3-fold higher (Table III). Additionally, an increased flow through the tricarboxylic acid cycle could be achieved by the activation of the γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) shunt, generating succinate from Glu via GABA. Activation of the GABA shunt is associated with stress conditions and seed desiccation (Angelovici et al., 2011; Fait et al., 2011) and has been shown to prevent ROS accumulation (Bouché et al., 2003). Our results showing that increase in cytosolic H2O2 in desiccating seeds triggers metabolic reprogramming indicate that APX6 is a major modulator of ROS signals in desiccating seeds. The new ROS signal, seen in apx6 seeds and resulting in reduced germination, revealed a strong cross talk with ABA signaling. This was initially suggested by stratification treatment, which almost completely alleviated the germination phenotype on soil (Fig. 2), and was further confirmed by increased sensitivity to ABA (Fig. 6; Supplemental Fig. S6). Correspondingly, germination of apx6 mutants was also hypersensitive to NaCl and sorbitol (Fig. 3). In contrast, ABA-insensitive mutants, such as abi4 and abi5, and ABA-deficient mutants, such as aba2, precariously germinate in the presence of NaCl or mannitol compared with wild-type seeds, which are protected by dormancy governed by ABA (Quesada et al., 2000; González-Guzmán et al., 2002; Tezuka et al., 2013).

Despite a 40% increase in the ABA content of dry apx6 seeds, the higher and more significant accumulation was observed for ABA breakdown products (Table I). This finding is in agreement with a previous report showing that H2O2 mediates ABA catabolism (Liu et al., 2010). In addition, H2O2 was shown to promote GA biosynthesis (Liu et al., 2010; Bahin et al., 2011), and indeed, the level of GA4 was 80% higher in apx6 compared with the wild type. However, ABA and GA are antagonistic; therefore, increased ABA homeostasis cannot solely account for the germination phenotype of apx6.

In contrast with ABA metabolic changes, only minor differences were observed between the wild type and apx6 in the expression of the ABA-responsive marker genes EM6 and RD29b and the dehydrin LEA protein (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, the transcript levels of ABI3 and ABI5 were relatively lower in dry and imbibed apx6 seeds, yet these seeds display reduced germination and enhanced ABA sensitivity.

ABI3 has long been recognized as a major regulator of seed dormancy and the ABA inhibition of seed germination (Bentsink and Koornneef, 2008). ABI5 functions downstream of ABI3, and in concert they promote dormancy and regulate the ABA-inducible expression of LEA proteins such as EM1 and EM6 (Gampala et al., 2002; Lopez-Molina et al., 2002). Taken together, our results suggest that the germination phenotype in apx6 mutants is not mediated by ABI3 but rather through another ABA-responsive signaling route.

In contrast, the level of ABI4 was elevated in dry and imbibed apx6 seeds. ABI4 was recently shown to positively regulate dormancy by promoting ABA synthesis (Shu et al., 2013). However, it is still debatable whether ABI4 actually affects seed dormancy (Liu et al., 2013). Interestingly, recent evidence has shown that ABI4 is involved in redox regulation and oxidative challenges in Arabidopsis leaves (Giraud et al., 2009; Foyer et al., 2012).

ABA synthesis and changes in ROS or redox are linked through AA (Arrigoni and De Tullio, 2000; Foyer et al., 2012; Ye and Zhang, 2012; Ye et al., 2012). The activity of the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase enzyme responsible for the oxidative cleavage of neoxanthin to xanthoxin in the ABA synthesis pathway depends on ascorbate (Arrigoni and De Tullio, 2000; Foyer et al., 2012). Nonetheless, in leaves of the AA-deficient mutant vitamin C defective1, the level of ABA was 60% higher than in the wild type, due to an increase in ABA synthesis transcripts, including that of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (Pastori et al., 2003). Seeds of apx6 mutants contained slightly less AA and more DHA than in the wild type, yet their total is comparable in both seed types (Supplemental Fig. S3). Potentially, the changes in the ratio between AA and DHA, acting as a redox couple signal, together with elevation in ABI4 expression, may increase the synthesis rate of ABA and its accumulation.

In addition to the changes in ABA metabolism and signaling, changes in auxin metabolism and signal perception (Table I; Fig. 7) were likely to affect the germination phenotype of apx6. Since Trp is the principal precursor for IAA biosynthesis routes (Korasick et al., 2013), its depletion in dry seeds of apx6 implies that the accumulation in the mutant was due to de novo synthesis. The possibility that oxidative conditions in apx6 seeds enhance auxin biosynthesis has yet to be examined and will be tested in the near future.

It was recently shown that high levels of auxin and the activation of IAA signaling enhance ABA-mediated dormancy by supporting the persistence of ABI3 expression during imbibition (Liu et al., 2013). Our observations indicate that both auxin and ABA are involved in the germination phenotype of the apx6 mutants. However, since ABI3 and ABI5 expression were relatively suppressed in apx6 seeds, it is likely that the cross talk between IAA and ABA does not involve activation of the ABI3 signaling route.

Interestingly, ABI4 was shown to regulate the development of Arabidopsis lateral roots by reducing polar auxin transport (Shkolnik-Inbar and Bar-Zvi, 2010). In addition, two recent studies revealed cross talk between auxin homeostasis and ROS in seed germination and primary root growth (He et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2013). Whether ABI4 participates in the regulation of auxin homeostasis in seeds remains to be determined.

Altered levels of auxin may also influence the vigor of apx6 seeds under stress conditions and further feed back on ROS generation. The involvement of IAA cross talk with H2O2 in plant stress tolerance was recently reviewed; however, the mechanistic details are not well understood (Krishnamurthy and Rathinasabapathi, 2013). Accumulation of mitochondrial ROS in an Arabidopsis ABA overly sensitive mutant, abo6, deficient in a splicing regulator of mitochondrial complex I rendered it sensitive to germination on ABA. Furthermore, abo6 showed a decrease in auxin availability, and the addition of auxin released the inhibition of germination (He et al., 2012). In contrast, the level of auxin homeostasis in APX6-deficient seeds increased, and the addition of IAA inhibited germination (Table I; Fig. 7). Therefore, we suggest that our findings point to a different node of this cross talk that is activated by an increase in cytosolic H2O2 and that is involved in dormancy, germination control, and the stress responsiveness of seeds. This further suggests that, under favorable conditions, the activation of this cross talk is suppressed by APX6 activity.

Our study adds to recent reports portraying a complex relationship between ROS, ABA, and other hormones in seed physiology. The cross talk unraveled in this study involving ROS, ABA, and IAA does not activate the ABI3-mediated dormancy program and, therefore, may constitute a novel interplay that is associated with oxidative stress in desiccating seeds. Consideration should be given to the involvement of other signals in the oxidative stress response in seeds, since the levels of GA and several cytokinins were also altered in the mutant (Table I). APX6 emerges as the dominant ascorbate peroxidase in mature drying seeds, protecting against stress and serving as a modulator of cellular signals. These newly discovered specialized roles in seeds for APX6, together with the replacement of APX1 with APX6 in mature desiccating wild-type seeds (Fig. 5), raise questions regarding the differences between these two enzymes. It might be that APX6 is better suited to withstand severe desiccation, a matter that will require further examination. Understanding the degree of redundancy versus specialization in family members such as APXs, peroxiredoxins, and NADPH oxidases will immensely increase our understanding of the plant ROS network activity in developmental and physiological challenges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, Germination Assays, and Stress Treatments

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia was used in this study. APX6 T-DNA insertion lines (apx6-1, WISCDSLOX321C09; apx6-2, WiscDsLox466F10; and apx6-3, WiscDsLox337H07) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (https://abrc.osu.edu/). Homozygous lines were PCR identified according to SIGnAL Laboratory recommendations (http://signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html).

The abi4-1 mutant was used as a germination control in the presence of ABA.

In all germination assays, the seeds were kept at 23°C under continuous low light (50 μmol m–2 s–1) with 70% relative humidity. Freshly harvested seeds were surface sterilized (4 min in 50% [v/v] ethanol and 3.4% [v/v] bleach mixture, rinsed with 100% [v/v] ethanol, and dried on filter paper) and sown on 0.5× MS agar (0.8% [w/v]) or directly placed on soil pellets (Jiffy 7000). All the germination experiments were conducted within 1 week from harvesting to preserve dormancy. Approximately 50 seeds in six to eight replicates were placed on 0.5× MS plates per line per treatment. Plates were supplemented with methyl viologen (Paraquat) for oxidative stress; with NaCl or sorbitol for osmotic stress; and with ABA or IAA (Sigma-Aldrich) for hormone sensitivity determination. The germination rate on MS agar was scored as radicle emergence observed with a dissecting microscope (Leica M80) and on soil as cotyledon greening. Germination on soil pellets took place without cover at 24°C at 70% humidity. HS on imbibed seeds was applied by incubating at 42°C for 6 to 48 h, following by transfer to 24°C for germination to progress.

Mature seeds were collected from plants grown in mixed soil (3:2:1, peat moss:vermiculite:perlite, v/v/v) and grown under controlled conditions in growth chambers (Percival E-30, AR-66; Percival Scientific): 24°C, 16/8-h light/dark cycle, 80 μmol m–2 s–1, and 70% relative humidity. The mutants and the wild type were always grown side by side. HS during seed maturation was done on 45-d-old plants bearing green mature stage 17 and 18 siliques (yellow siliques were removed prior to treatment) grown in chambers as described above. Gradual HS was applied according to the following program: light, 6 to 8 am, 28°C; 8 to 10 am, 32°C; 10 am to 12 noon, 36°C; 12 noon to 4 pm, 39°C or 42°C; 4 to 6 pm, 36°C; 6 to 8 pm, 32°C; 8 to 10 pm, 28°C; dark, 10 pm to 6 am, 23°C. Seeds were collected after 5 and 6 d.

Molecular and Biochemical Analyses

RNA extraction from dry seeds was carried out according to the TRIzol-based method described previously (Meng and Feldman, 2010). All other RNA extractions, PCR, complementary DNA synthesis, and real-time PCR were done as described previously (Miller et al., 2009). First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA (treated with RNase-free DNase; New England Biolabs) at 42°C with Promega MV-Reverse Transcriptase. Real-time PCR was performed on the Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System with 40 cycles and an annealing temperature of 60°C. Cycle threshold values were determined by CFX Manager Software assuming 100% primer efficiency.

Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Extraction of total protein, western blotting, and protein oxidation analyses were done as described previously (Miller et al., 2007).

Determination of relative H2O2 concentrations and relative total peroxidase activity was performed as described previously (Xiong et al., 2007) with minor modifications. The dry seeds (2–3 mg) were crushed with 0.1 mL of 0.2 m HClO4, incubated on ice for 5 min, and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000g and 4°C. The supernatant was neutralized with 0.2 m KOH and was centrifuged again at 12,000g for 1 min. Quantification of H2O2 in extracts was performed using a reaction with the Amplex Red reagent (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) with three technical repeats and six biological replicates. Samples were measured with the Synergy 4 fluorescence plate reader (Bio-Tek) using 530/590-nm excitation/emission.

Relative peroxidase activity in total protein extracts from dry seeds was determined according to Liu et al. (2010) with modifications. H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 2 mm to extracts containing 200 µm Amplex Red on microplates, and fluorescence generation was measured as described above. The relative enzymatic activity of peroxidases was normalized to the total amount of protein.

Relative superoxide concentration was determined according to Bournonville and Díaz-Ricci (2011) with minor modifications. About 5 mg of dry seeds was crushed with 0.5 mg mL−1 nitroblue tetrazolium prepared in 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Fomazan was extracted using 1 mL of 2 m potassium hydroxide:chloroform (1:1, v/v). Chloroformic extracts were light protected and completely dried in vacuum at room temperature. The solid residue was dissolved in 350 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide and 300 mL of 2 m potassium hydroxide at room temperature and immediately analyzed with a Synergy 4 spectrophotometer. Formazan quantification was performed at 630 nm.

AA levels were determined calorimetrically as described previously (Gillespie and Ainsworth, 2007) with the following minor adaptation for seeds: 40 mg of dry seeds was used for the extraction and was extracted to a final volume of 1 mL.

GC-MS and Data Analysis of Primary Metabolites, Including Amino Acids

Seeds from apx6-1 and wild-type lines were pooled from at least 100 pods. Free amino acids were extracted from 20 mg of dry seeds. The amino acids were detected using the single-ion method of GC-MS, as described previously (Amira et al., 2005). For reduced glutathione determination, dry seeds (25 mg) were ground with a mortar and pestle and then extracted and analyzed by HPLC, as described previously (Matityahu et al., 2013). For primary metabolite analysis, samples were prepared as described for the free amino acids and 7 μL of a retention time standard mixture (0.2 mg mL−1 n-dodecane, n-pentadecane, n-nonadecane, n-docosane, and n-octacosane) in pyridine. In addition, 4.6 μL of a retention time standard mixture of nor-Leu and ribitol (2 mg mL−1) was added prior to trimethylsilylation. Samples were run on a GC-MS system (Agilent 7890A series gas chromatography system coupled with Agilent 5975c Mass Selective Detector), and a Gerstel multipurpose sampler (MPS2) was installed on this system as described previously (Matityahu et al., 2013). The data collected were obtained using the Agilent GC/MSD Productivity ChemStation software. All peaks above the baseline threshold were quantified and grouped according to retention time, with areas normalized to nor-Leu and ribitol. Substances were identified by comparison with standards and were also compared with the commercially available electron mass spectrum libraries from the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Wiley Registry of Mass Spectral Data.

Plant Hormone Analysis

Seed samples were purified and analyzed essentially as described previously (Dobrev and Kamínek, 2002; Dobrev and Vankova, 2012). Dry seeds (30 mg) were homogenized with a ball mill (MM301; Retsch) and extracted in cold (−20°C) extraction buffer consisting of methanol:water:formic acid (15:4:1, v/v/v). To account for sample losses and for quantification by isotope dilution, the following stable isotope-labeled internal standards (10 pmol per sample) were added: [13C6]IAA (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), [2H6]ABA, [2H2]GA4, [2H2]GA8, [2H2]GA19, [2H5]trans-zeatin, [2H5]trans-zeatin riboside, [2H5]trans-zeatin-7-glucoside, [2H5]trans-zeatin-9-glucoside, [2H5]trans-zeatin-O-glucoside, [2H5]trans-zeatin riboside-O-glucoside, [2H5]trans-zeatin riboside monophosphate, [2H3]dihydrozeatin, [2H3]dihydrozeatin riboside, [2H3]dihydrozeatin-9-glucoside, [2H6]isopentenyl adenine, [2H6]isopentenyl adenosine, [2H6]isopentenyl adenine-7-glucoside, [2H6]isopentenyl adenine-9-glucoside, and [2H6]isopentenyl adenosine monophosphate (Olchemim). Extract was evaporated in a vacuum concentrator (Alpha RVC; Christ). Sample residue was dissolved into 1 mL of 0.1 m formic acid and applied to a mixed-mode reverse-phase cation-exchange solid-phase extraction column (Oasis-MCX; Waters). Two hormone fractions were eluted sequentially: (1) fraction A, eluted with methanol, containing hormones of acidic and neutral character (auxins, ABA, and GA); and (2) fraction B, eluted with 0.35 m NH4OH in 60% (v/v) methanol, containing hormones of basic character (cytokinins). Fractions were evaporated to dryness in the vacuum concentrator and dissolved into 30 µL of 10% (v/v) methanol. An aliquot (10 µL) from each fraction was separately analyzed by HPLC (Ultimate 3000; Dionex) coupled to a hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (3200 Q TRAP; Applied Biosystems) set in selected reaction monitoring mode. Quantification of hormones was done using the isotope dilution method with multilevel calibration curves (r2 > 0.99). Data processing was carried out with Analyst 1.5 software (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

Principal component analysis of GC-MS data was done by MetaboAnalyst 2.0 (http://metaboanalyst.ca; Xia et al., 2009, 2012) on the log-transformed (base 10) data sets and pareto scaling (mean centered and divided by the square root of sd of each variable) manipulation.

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifiers for the genes mentioned in this article are as follows: APX1 (At1g07890), APX2 (At3g09640), APX6 (At4g32320), UBIQUITIN5 (At3g62250), ACTIN2 (AT3G18780), MBF1c (At3g24500), ABI3 (At3g24650), ABI4 (At2g40220), ABI5 (At2g36270), DRE BINDING FACTOR 1B (DREB1B) (At4g25490) DREB2B (At3g11020), EM6 (At2g40170), LEA (At2g21490), Rd29b (At5g52300), and AOX1a (At3g22370).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Mature wild-type and apx6 plants grown under control conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. Total peroxidase activity in dry seeds of the wild type and apx6.

Supplemental Figure S3. AA and glutathione levels in dry seeds.

Supplemental Figure S4. Genevestigator developmental expression plot of AtAPXs.

Supplemental Figure S5. Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph browser developmental expression pattern of cAPXs in the wild type.

Supplemental Figure S6. Germination of stratified seeds on 0.5 µm ABA.

Supplemental Figure S7. Principal component analysis of metabolites.

Supplemental Figure S8. Effect of HS during seed imbibition on germination.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer list and sequences.

Glossary

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ABA

abscisic acid

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- cAPX

cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase

- T-DNA

transfer DNA

- DAI

days after imbibition

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- AA

ascorbic acid

- HAI

hours after imbibition

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- BCAAs

branched-chain amino acids

- HS

heat stress

- GABA

γ-aminobutyrate

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Marie Curie Actions-International Career Integration Grant (grant no. 293999), the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 938/11), and the Czech Science Foundation (project no. 206/09/2062).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Amira G, Ifat M, Tal A, Hana B, Shmuel G, Rachel A. (2005) Soluble methionine enhances accumulation of a 15 kDa zein, a methionine-rich storage protein, in transgenic alfalfa but not in transgenic tobacco plants. J Exp Bot 56: 2443–2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelovici R, Fait A, Fernie AR, Galili G. (2011) A seed high-lysine trait is negatively associated with the TCA cycle and slows down Arabidopsis seed germination. New Phytol 189: 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelovici R, Galili G, Fernie AR, Fait A. (2010) Seed desiccation: a bridge between maturation and germination. Trends Plant Sci 15: 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni O, De Tullio MC. (2000) The role of ascorbic acid in cell metabolism: between gene-directed functions and unpredictable chemical reactions. J Plant Physiol 157: 481–488 [Google Scholar]

- Baena-González E, Sheen J. (2008) Convergent energy and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci 13: 474–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahin E, Bailly C, Sotta B, Kranner I, Corbineau F, Leymarie J. (2011) Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and hormonal signalling pathways regulates grain dormancy in barley. Plant Cell Environ 34: 980–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly C, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Corbineau F. (2008) From intracellular signaling networks to cell death: the dual role of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. C R Biol 331: 806–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin J, Langlade N, Vincourt P, Arribat S, Balzergue S, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Bailly C. (2011) Targeted mRNA oxidation regulates sunflower seed dormancy alleviation during dry after-ripening. Plant Cell 23: 2196–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L, Koornneef M. (2008) Seed dormancy and germination. The Arabidopsis Book 6: e0119, /10.1199/tab.0050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N, Fait A, Bouchez D, Møller SG, Fromm H. (2003) Mitochondrial succinic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase of the gamma-aminobutyrate shunt is required to restrict levels of reactive oxygen intermediates in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6843–6848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bournonville CF, Díaz-Ricci JC. (2011) Quantitative determination of superoxide in plant leaves using a modified NBT staining method. Phytochem Anal 22: 268–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Yang L, Ahmad P, Wan X, Hu X. (2011) Proteomic profiling and redox status alteration of recalcitrant tea (Camellia sinensis) seed in response to desiccation. Planta 233: 583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandoy E, Schyns R, Deltour R, Verly WG. (1987) Appearance and repair of apurinic apyrimidinic sites in DNA during early germination of Zea mays. Mutat Res 181: 57–60 [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, Shulaev V, Schlauch K, Mittler R. (2005) Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 268–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev PI, Kamínek M. (2002) Fast and efficient separation of cytokinins from auxin and abscisic acid and their purification using mixed-mode solid-phase extraction. J Chromatogr A 950: 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev PI, Vankova R. (2012) Quantification of abscisic acid, cytokinin, and auxin content in salt-stressed plant tissues. Methods Mol Biol 913: 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Meimoun P, Job C, Job D, Bailly C. (2013) Role of protein and mRNA oxidation in seed dormancy and germination. Front Plant Sci 4: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fait A, Nesi AN, Angelovici R, Lehmann M, Pham PA, Song L, Haslam RP, Napier JA, Galili G, Fernie AR. (2011) Targeted enhancement of glutamate-to-γ-aminobutyrate conversion in Arabidopsis seeds affects carbon-nitrogen balance and storage reserves in a development-dependent manner. Plant Physiol 157: 1026–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage WE, Leubner-Metzger G. (2006) Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol 171: 501–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, Steber C. (2008) Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 387–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Kerchev PI, Hancock RD. (2012) The ABA-INSENSITIVE-4 (ABI4) transcription factor links redox, hormone and sugar signaling pathways. Plant Signal Behav 7: 276–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili G. (2011) The aspartate-family pathway of plants: linking production of essential amino acids with energy and stress regulation. Plant Signal Behav 6: 192–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gampala SS, Finkelstein RR, Sun SS, Rock CD. (2002) ABI5 interacts with abscisic acid signaling effectors in rice protoplasts. J Biol Chem 277: 1689–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie KM, Ainsworth EA. (2007) Measurement of reduced, oxidized and total ascorbate content in plants. Nat Protoc 2: 871–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud E, Van Aken O, Ho LH, Whelan J. (2009) The transcription factor ABI4 is a regulator of mitochondrial retrograde expression of ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE1a. Plant Physiol 150: 1286–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guzmán M, Apostolova N, Bellés JM, Barrero JM, Piqueras P, Ponce MR, Micol JL, Serrano R, Rodríguez PL. (2002) The short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase ABA2 catalyzes the conversion of xanthoxin to abscisic aldehyde. Plant Cell 14: 1833–1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Duan Y, Hua D, Fan G, Wang L, Liu Y, Chen Z, Han L, Qu LJ, Gong Z. (2012) DEXH box RNA helicase-mediated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis mediates crosstalk between abscisic acid and auxin signaling. Plant Cell 24: 1815–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth MJ, Bentsink L, Soppe WJ. (2008) Molecular networks regulating Arabidopsis seed maturation, after-ripening, dormancy and germination. New Phytol 179: 33–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi Y, Tawaratsumida T, Kondo K, Kasa S, Sakamoto M, Aoki N, Zheng SH, Yuasa T, Iwaya-Inoue M. (2012) Reactive oxygen species are involved in gibberellin/abscisic acid signaling in barley aleurone cells. Plant Physiol 158: 1705–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Sun L, Song Y, Wang L, Liu L, Zhang L, Liu B, Li N, Miao C, Hao F. (2013) AtrbohD and AtrbohF positively regulate abscisic acid-inhibited primary root growth by affecting Ca2+ signalling and auxin response of roots in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 64: 4183–4192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job C, Rajjou L, Lovigny Y, Belghazi M, Job D. (2005) Patterns of protein oxidation in Arabidopsis seeds and during germination. Plant Physiol 138: 790–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V, Joung JG, Fei Z, Jander G. (2010) Interdependence of threonine, methionine and isoleucine metabolism in plants: accumulation and transcriptional regulation under abiotic stress. Amino Acids 39: 933–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korasick DA, Enders TA, Strader LC. (2013) Auxin biosynthesis and storage forms. J Exp Bot 64: 2541–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy A, Rathinasabapathi B. (2013) Oxidative stress tolerance in plants: novel interplay between auxin and reactive oxygen species signaling. Plant Signal Behav 8: 4161–, 25761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariguet P, Ranocha P, De Meyer M, Barbier O, Penel C, Dunand C. (2013) Identification of a hydrogen peroxide signalling pathway in the control of light-dependent germination in Arabidopsis. Planta 238: 381–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann S, Funck D, Szabados L, Rentsch D. (2010) Proline metabolism and transport in plant development. Amino Acids 39: 949–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leymarie J, Vitkauskaité G, Hoang HH, Gendreau E, Chazoule V, Meimoun P, Corbineau F, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Bailly C. (2012) Role of reactive oxygen species in the regulation of Arabidopsis seed dormancy. Plant Cell Physiol 53: 96–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Yang L, Paul M, Zu Y, Tang Z. (2013) Ethylene promotes germination of Arabidopsis seed under salinity by decreasing reactive oxygen species: evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide simulated by sodium nitroprusside. Plant Physiol Biochem 73: 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhou J, Xing D. (2012) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase plays a vital role in regulation of rice seed vigor via altering NADPH oxidase activity. PLoS ONE 7: e33817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Feng Z, Li Q, Yang HQ, Luan S, Li J, He ZH. (2013) Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 15485–15490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ye N, Liu R, Chen M, Zhang J. (2010) H2O2 mediates the regulation of ABA catabolism and GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seed dormancy and germination. J Exp Bot 61: 2979–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, McLachlin DT, Chait BT, Chua NH. (2002) ABI5 acts downstream of ABI3 to execute an ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination. Plant J 32: 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matityahu I, Godo I, Hacham Y, Amir R. (2013) Tobacco seeds expressing feedback-insensitive cystathionine gamma-synthase exhibit elevated content of methionine and altered primary metabolic profile. BMC Plant Biol 13: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Feldman L. (2010) A rapid TRIzol-based two-step method for DNA-free RNA extraction from Arabidopsis siliques and dry seeds. Biotechnol J 5: 183–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Schlauch K, Tam R, Cortes D, Torres MA, Shulaev V, Dangl JL, Mittler R. (2009) The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD mediates rapid systemic signaling in response to diverse stimuli. Sci Signal 2: ra45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Shulaev V, Mittler R. (2008) Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol Plant 133: 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. (2010) Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ 33: 453–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Suzuki N, Rizhsky L, Hegie A, Koussevitzky S, Mittler R. (2007) Double mutants deficient in cytosolic and thylakoid ascorbate peroxidase reveal a complex mode of interaction between reactive oxygen species, plant development, and response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol 144: 1777–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Gollery M, Van Breusegem F. (2004) Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci 9: 490–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oracz K, El-Maarouf Bouteau H, Farrant JM, Cooper K, Belghazi M, Job C, Job D, Corbineau F, Bailly C. (2007) ROS production and protein oxidation as a novel mechanism for seed dormancy alleviation. Plant J 50: 452–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oracz K, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Kranner I, Bogatek R, Corbineau F, Bailly C. (2009) The mechanisms involved in seed dormancy alleviation by hydrogen cyanide unravel the role of reactive oxygen species as key factors of cellular signaling during germination. Plant Physiol 150: 494–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchuk II, Volkov RA, Schöffl F. (2002) Heat stress- and heat shock transcription factor-dependent expression and activity of ascorbate peroxidase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 838–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhey S, Naithani SC, Keshavkant S. (2012) ROS production and lipid catabolism in desiccating Shorea robusta seeds during aging. Plant Physiol Biochem 57: 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastori GM, Kiddle G, Antoniw J, Bernard S, Veljovic-Jovanovic S, Verrier PJ, Noctor G, Foyer CH. (2003) Leaf vitamin C contents modulate plant defense transcripts and regulate genes that control development through hormone signaling. Plant Cell 15: 939–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada V, Ponce MR, Micol JL. (2000) Genetic analysis of salt-tolerant mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 154: 421–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajjou L, Duval M, Gallardo K, Catusse J, Bally J, Job C, Job D. (2012) Seed germination and vigor. Annu Rev Plant Biol 63: 507–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajjou L, Gallardo K, Debeaujon I, Vandekerckhove J, Job C, Job D. (2004) The effect of α-amanitin on the Arabidopsis seed proteome highlights the distinct roles of stored and neosynthesized mRNAs during germination. Plant Physiol 134: 1598–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shuman J, Shulaev V, Davletova S, Mittler R. (2004) When defense pathways collide: the response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Physiol 134: 1683–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarath G, Hou G, Baird LM, Mitchell RB. (2007) ABA, ROS and NO are key players during switchgrass seed germination. Plant Signal Behav 2: 492–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnik-Inbar D, Bar-Zvi D. (2010) ABI4 mediates abscisic acid and cytokinin inhibition of lateral root formation by reducing polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22: 3560–3573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Zhang H, Wang S, Chen M, Wu Y, Tang S, Liu C, Feng Y, Cao X, Xie Q. (2013) ABI4 regulates primary seed dormancy by regulating the biogenesis of abscisic acid and gibberellins in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 9: e1003577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah V, Reddy KJ. (2010) Interactions between ethylene, abscisic acid and cytokinin during germination and seedling establishment in Arabidopsis. J Biosci 35: 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Miller G, Salazar C, Mondal HA, Shulaev E, Cortes DF, Shuman JL, Luo X, Shah J, Schlauch K, et al. (2013b) Temporal-spatial interaction between reactive oxygen species and abscisic acid regulates rapid systemic acclimation in plants. Plant Cell 25: 3553–3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Miller G, Sejima H, Harper J, Mittler R. (2013a) Enhanced seed production under prolonged heat stress conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana plants deficient in cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 2. J Exp Bot 64: 253–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Rivero RM, Shulaev V, Blumwald E, Mittler R. (2014) Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol 203: 32–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezuka K, Taji T, Hayashi T, Sakata Y. (2013) A novel abi5 allele reveals the importance of the conserved Ala in the C3 domain for regulation of downstream genes and salt tolerance during germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav 8: e23455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderauwera S, Suzuki N, Miller G, van de Cotte B, Morsa S, Ravanat JL, Hegie A, Triantaphylidès C, Shulaev V, Van Montagu MC, et al. (2011) Extranuclear protection of chromosomal DNA from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 1711–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ. (2007) An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS ONE 2: e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Mandal R, Sinelnikov IV, Broadhurst D, Wishart DS. (2012) MetaboAnalyst 2.0: a comprehensive server for metabolomic data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 40: W127–W133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. (2009) MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res 37: W652–W660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Contento AL, Nguyen PQ, Bassham DC. (2007) Degradation of oxidized proteins by autophagy during oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N, Zhang J. (2012) Antagonism between abscisic acid and gibberellins is partially mediated by ascorbic acid during seed germination in rice. Plant Signal Behav 7: 563–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N, Zhu G, Liu Y, Zhang A, Li Y, Liu R, Shi L, Jia L, Zhang J. (2012) Ascorbic acid and reactive oxygen species are involved in the inhibition of seed germination by abscisic acid in rice seeds. J Exp Bot 63: 1809–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Hennig L, Gruissem W. (2004) GENEVESTIGATOR: Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol 136: 2621–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]