Abstract

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a histological pattern of injury on renal biopsy that can arise from a diverse range of causes and mechanisms. Although primary and secondary forms are described based on the underlying cause, there are many common factors that underlie the development of this segmental injury. In this review we will describe the currently accepted model for the pathogenesis of classic FSGS and review the data supporting this model. Although the podocyte is considered the major target of injury in FSGS, we will also highlight the contributions of other resident glomerular cells in the development of FSGS.

Introduction

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is not due to a specific glomerular disease, but rather refers to a morphological/histological pattern of injury recognized on kidney biopsy that is characterized by sclerotic (fibrotic) lesions in glomeruli that are focal (less than 50% of all glomeruli affected on light microscopy) and segmental (less than 50% of the glomerular tuft affected). This pathological pattern has been further classified by the Columbia group according to specific pathological light microscopic findings (tip lesion, cellular, collapsing, perihilar, and not otherwise specified) which might have diagnostic and prognostic utility (see review in this issue written by D'Agati et al).1 with a very different pathogenesis. This review will focus on the pathogenesis of the more classical forms of FSGS. Clinicians also commonly classify FSGS according to known Many consider collapsing glomerulopathy to be a separate entity etiological factors as a guide to deciding which patients to offer immunosuppression (Table 1). Patients with primary FSGS (no known cause identified to date) often present acutely with severe nephrotic syndrome whereas secondary forms of FSGS (causes known) typically have a more chronic presentation. There is significant overlap in these clinical presentations, and the development of the sclerotic FSGS lesion in the glomerulus may have common pathophysiological mechanisms. In this review we will focus on the pathogenesis of the segmental glomerular lesions and analyze the experimental and clinical data supporting this view.

Table 1.

Classification of FSGS by Underlying Cause

| Classification | Etiology | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | ? Circulating permeability factor | • Idiopathic |

| Secondary | Glomerular Hyperfiltration | • Reduced nephron mass ○ Congenital (low birth weight, renal dysplasia) ○ Acquired nephron loss (e.g. reflux nephropathy, diabetic kidney disease) • Adaptive response (obesity, sickle cell disease, cyanotic congenital heart disease) |

| Viral infection | • HIV, parvovirus B19, CMV | |

| Drugs & Toxins | • heroin, pamidronate, lithium, anabolic steroids | |

| Familial | Podocyte gene disorders | • Nephrin, podocin, IFN2, α-actinin-4, CD2AP, WT1; TRPC6; phospholipase Cε1 |

Morphological studies place podocytes at the center of FSGS

Seminal morphological studies in experimental animals, by Wilhelm Kriz in the 1990's, laid the ground work for the current view of pathogenesis for classic FSGS (also called the not otherwise specific (NOS) variant of FSGS). 2,3 These studies, confirmed in human FSGS that recurs post kidney transplant 4, have shown that podocyte injury exemplified by cell body attenuation, foot process effacement, pseudocyst formation and microvillous transformation, is the earliest feature of FSGS. In human FSGS, these electron microscopic findings may be seen weeks to months prior to the development of visible lesions by light microscopy. If the podocyte does not recover from this initial/early injury, the resultant cell death and/or detachment leads to a reduction in podocyte number and a mismatch between podocyte coverage and the underlying glomerular basement membrane (GBM) surface area, leading to “uncovered” bare areas of GBM (Figure 1). Possibly due to loss of structural support by overlying podocytes at these sites, the capillary loop may bulge toward Bowman's capsule (ballooning) and an early connection (cell bridge) forms between the cells lining Bowman's capsule (the parietal epithelial cells, abbreviated herein as PECs) and the podocyte deprived areas of GBM. Taken together, these studies highlight that the initiating events in classic FSGS are in podocytes. Their contribution to the evolution of the FSGS lesion is well known (and will be discussed below), but other resident glomerular cells participate in the underlying pathogenesis of this lesion.

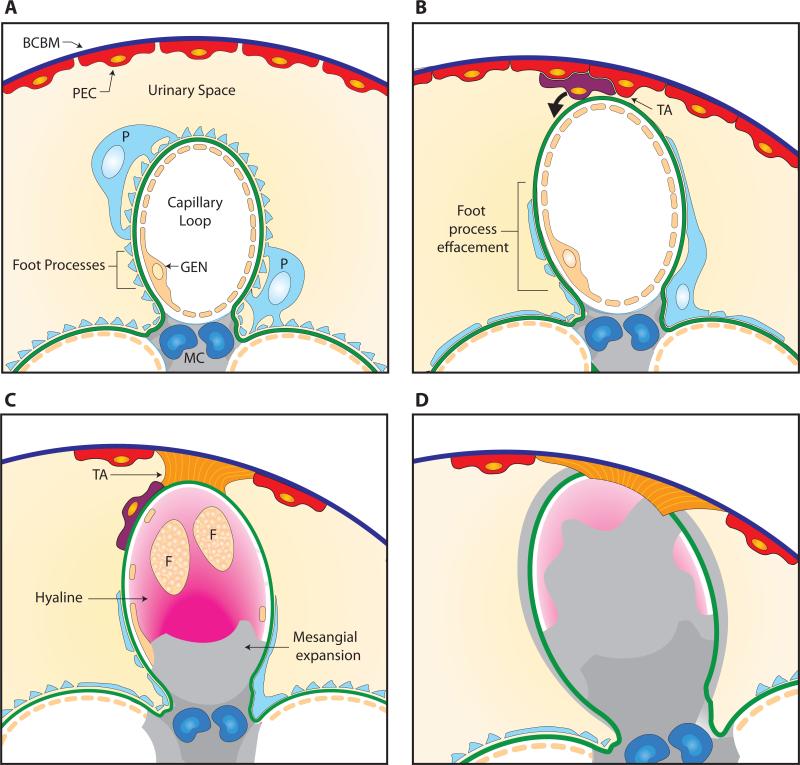

Figure 1. Pathogenesis of FSGS.

Panel A: Normal capillary loop (segment) within a glomerulus showing glomerular basement membrane (GBM) lined by the fenestrated endothelium (GEN) and covered by a podocyte (P) with intact foot processes. Mesangial cells (MC) support capillary loop. Bowman's capsule basement membrane (BCBM) is covered with parietal epithelial cells (PECs). Panel B: Podocyte injury with foot process effacement (FPE) leads to loss of podocyte coverage (cell death or detachment) and an area of uncovered GBM. A tuft adhesion (TA) forms between PECs and the uncovered GBM. Panel C: PECs deposit matrix leading to a broad fibrous tuft attachment (TA). Some PECs migrate onto the glomerular tuft via the attachment and deposit matrix on the glomerular segment on the outside of the GBM. Deposition of fibrillar collagen leads to mesangial expansion reducing capillary lumen. Hyalinosis (trapped plasma proteins) and foam cells (F) obliterate capillary lumen. Panel D: Fully formed segmental sclerosis (fibrosis) with collapse of capillary lumen and areas of trapped hyaline.

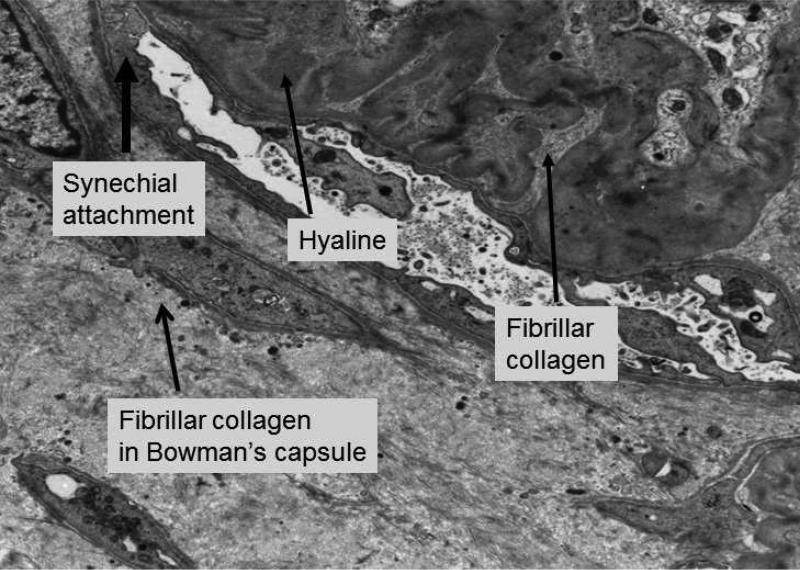

The glomerular parietal epithelial cells (PECs) forming the cell bridge can deposit matrix between these bridging cells to form a fibrous attachment (tuft adhesion) between the glomerular tuft and Bowman's capsule (Figures 2 & 3). The tuft adhesion is considered the earliest feature of FSGS seen on light microscopy in human biopsies. A suggested consequence of the adherence PEC's to the naked areas of GBM, is the formation of gaps in the parietal epithelium into which glomerular filtrate from attached capillary loops can traverse (misdirected filtration). This leads to stripping of PEC's off the Bowman's basement membrane, the formation of proteinaceous pseudo-crescents, and the spreading of filtrate along the tubular basement membrane (peritubular filtrate spreading) resulting in tubular atrophy. Accumulation of proteinaceous material in the adherent capillary loop (hyalinosis), the deposition of extracellular matrix, and the accumulation of intracapillary foam cells (lipid-laden macrophages) leads to obliteration of capillary loops, the characteristic lesion of segmental sclerosis. Mesangial expansion due to increased matrix is commonly noted. In FSGS, the sclerosis is by definition segmental and other portions of the glomerular tuft appear normal, although this lesion may progress to global glomerulosclerosis over time. Taken together, FSGS involves several glomerular cell types and other structures, all which will be considered in the overall pathogenesis of this glomerular lesion in this review.

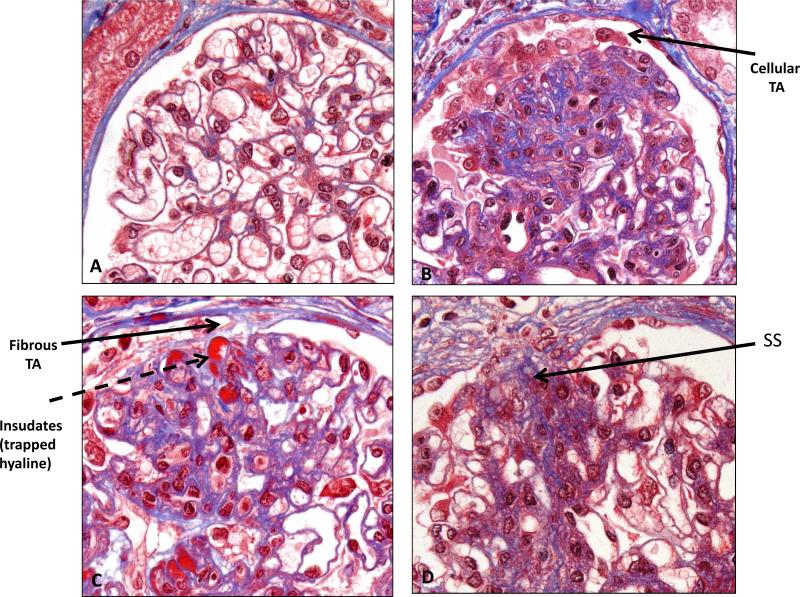

Figure 2. Formation of FSGS lesion.

Light microscopy (Trichrome stain). Panel A: Normal glomerulus showing multiple open capillary loops (compare with single loop in Figure 1). Panel B: A cellular tuft adhesion (TA) forms between parietal epithelial cells (PECs) and capillary loop(s) with early matrix deposition. Panel C: Further deposition of matrix by PECs leads to formation of fibrous tuft adhesion, with underlying insudates of trapped hyaline. Panel D: Area of segmental sclerosis (SS) within glomerulus, with adherence to Bowman's capsule.

Initiating mechanisms of podocyte injury

With the rapid advances in molecular biology over the last two decades, let us now review some of the data supporting this “podocyte depletion model” of FSGS.

Podocyte injury is the earliest morphological feature of FSGS, which has led to the current paradigm that classic FSGS is primarily a podocyte disorder, at least initially. A wide range of genetic and acquired cellular causative insults have been identified (Table 1) Hyperglycemia and insulin signaling, mechanical stress, angiotensin II, calcium signaling, viral infection, toxins, oxidants, and immunological injury are all well described. A wide range of disease states can therefore lead to the development of the FSGS pattern of injury reflecting the difficulties of classification of this group of disparate conditions. Due to space limitations, we shall highlight three of several potential factors that can predispose to the development of the FSGS lesion.

Genetic causes of FSGS: defects in constitutive podocyte proteins

Genetic studies of familial FSGS have identified multiple disease causing genes that are primarily expressed in the podocyte. Many of these gene products encode critical structural podocyte elements including the slit diaphragm (nephrin, podocin, CD2AP, TRPC6, GLEPP1, MYO1E), actin cytoskeleton (α-actinin 4, formin, myosin IIA, ARHGAP24, ARHGDIA), or foot process-GBM interaction (LAMB2, ITGA3). Notably, the clinical presentation in each of these disorders is variable. For example, mutations in genes encoding proteins of the slit diaphragm often lead to early onset disease, whereas gene disorders of the actin cytoskeleton more commonly lead to disease onset in adulthood, suggesting the requirement of additional podocyte insults to generate this condition. Notably, the majority of these hereditary podocytopathies are resistant to immunosuppression. 5

Genetic variation in the APOL1 gene in African American patients is a major risk factor for the development of FSGS and hypertensive nephrosclerosis, and correlates with the rate of progression of both diabetic and non-diabetic kidney disease. 6 The exact mechanisms leading to podocyte injury are yet to be determined, however, ApoL1 is expressed by the podocyte. 7 Notably, these kidney disease-associated ApoL1 variants lyse Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and a survival benefit of this polymorphism in Africans (similar to sickle cell trait and malaria) likely contributes to the high rate of kidney disease in this population.

Circulating Permeability Factors

A circulating permeability factor has long been implicated in primary FSGS. The major pieces of evidence supporting this include: (1) primary FSGS can recur very rapidly after kidney transplantation, (2) injection of plasma or plasma fractions from patients with FSGS into rats causes proteinuria, (3) sera from patients with FSGS increase albumin permeability in an isolated glomerulus model ex vivo, and (4) a transient nephrotic syndrome has been transmitted to a newborn from a mother with FSGS (reviewed in8). The soluble urokinase plasminogen-activator receptor (suPAR) is a recent candidate. Podocytes adhere tightly to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) via interactions between the actin cytoskeleton, integrins α3β1 and αvβ3, and the GBM components laminin 521 and type IV collagen. Wei et al showed that enhanced αvβ3 integrin signaling within podocytes is associated with foot process effacement and the development of proteinuria. 9 They showed that ß3 integrin signaling may be activated by both membrane bound urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) on podocytes and circulating (soluble) uPAR fragments (suPAR). 10 In uPAR null mice, chronic suPAR overexpression or administration resulted in a glomerulopathy with foot process effacement, proteinuria and other features of FSGS, which could be ameliorated with a uPAR-specific monoclonal antibody. Although there are questions over the suPAR bioassay, several, but not all, studies have confirmed high levels of suPAR in patients with FSGS (reviewed in 11).

Glomerulomegaly and Mechanical Stretch: Podocyte and GBM mismatch

The podocyte with its contractile actin cytoskeleton plays a critical role in counteracting the hemodynamic forces encountered by the glomerular capillary. According to the Brenner hypothesis of glomerular hyperfiltration, chronic glomerular hypertension leads to progressive glomerular injury that can be ameliorated with blockade of the renin angiotensin system. 12 In experimental models, chronic hypertension can lead to FSGS, possibly due to mechanical stretch of podocytes. 13 In vitro, mechanical stretch has been shown to lead to podocyte injury with activation of a local renin angiotensin system 14 and overexpression of the AT1 receptor within the podocyte causes glomerulosclerosis. 15 Notably, angiotensin inhibition is still renoprotective in models of FSGS where the AT1 receptor has been specifically deleted from podocytes suggesting other beneficial effects of angiotensin blockade. 16

When an increase in glomerular tuft size (glomerulomegaly) occurs, the resultant increase in GBM surface area provides a challenge to the resident podocyte population to ensure adequate GBM coverage. As podocyte proliferation is limited, cell hypertrophy becomes an important protective response, at least initially (later hypertrophy is maladaptive). In order to hypertrophy, the cell must re-enter the cell cycle, but instead of progressing to mitosis, the cell arrests at the G1 or G2/M restriction point. This entry into the cell cycle is associated with reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton with the associated risks of detachment or mitotic catastrophe leading to cell death. 17 The protective role of podocyte hypertrophy has been highlighted in an aging rat model in which the increase in glomerular tuft volume with aging is matched by podocyte hypertrophy. By inhibiting this protective podocyte hypertrophic response using a podocyte targeted inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), Fukuda et al demonstrated the elaboration of albuminuria and FSGS developing along the classic pathways of bare GBM, formation of tuft adhesions and segmental sclerosis. 18 Slowing glomerular enlargement with calorie restriction in these transgenic rats leads to abrogation of glomerulosclerosis.

Human conditions typically associated with glomerulomegaly include obesity, hypertension and the reduced nephron number (oligonephronia) seen in low birth weight subjects. 19 The combination of glomerulomegaly and mechanical stretch from glomerular hyperfiltration may play important pathogenic roles in the development of what has been described as secondary FSGS.

Consequences of podocyte injury

In the adult human kidney, there are approximately 500-600 podocytes per glomerular tuft, and the turnover of adult podocytes has never been demonstrated under physiological conditions. As adult podocytes are terminally differentiated epithelial cells with a very limited ability to proliferate, podocyte loss following injury can result in a reduction in podocyte number. Following podocyte injury from a diverse range of causes, a stereotypical podocyte response is often seen (Figure 4). These can be described as follows:

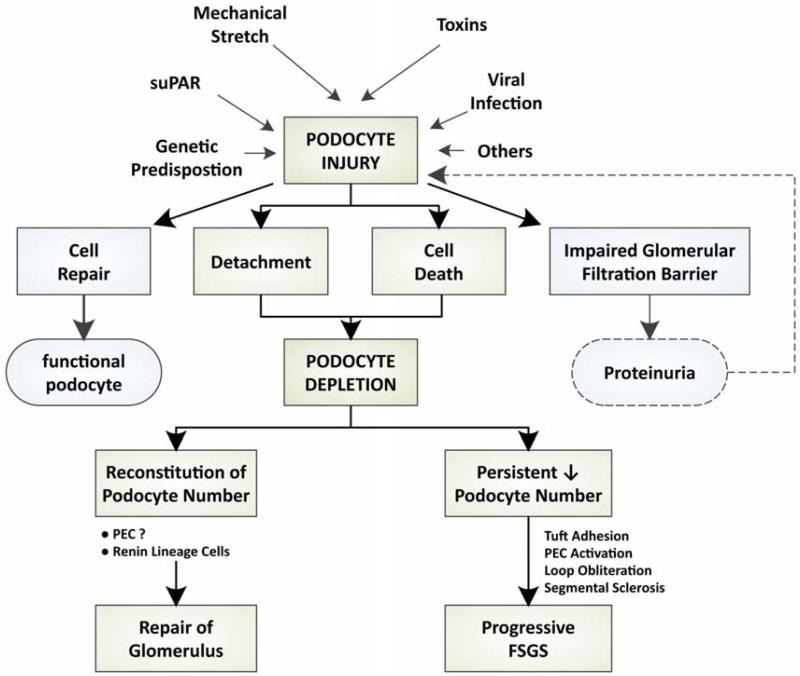

Figure 4. Persistent podocyte depletion results in FSGS.

Multiple etiologies may cause podocyte injury resulting in podocyte depletion. Alterations in the glomerular filtration barrier lead to proteinuria which can further podocyte injury. Reconstitution of podocyte number may lead to recovery of glomerular architecture and function, whereas persistent podocyte depletion produces a cascade of steps leading to an FSGS lesion (see Figure 1).

Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton

The prominent actin cytoskeleton is critical to the preservation of the highly differentiated shape of the mature podocyte. Many modes of injury converge to reorganize this scaffold, resulting in classical podocyte morphological changes such as cell body simplification and foot process effacement. Recent studies have emphasized the role of a family of Rho-GTPases in the control of actin remodeling. 20 Familial FSGS due to mutations in genes regulating the role of Rho-GTPases in podocytes have now been described. 21,22

Disruption of the glomerular filtration barrier

Loss of integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier leads to increased permeability of proteins. Studies have suggested that proteinuria is not only a biomarker of podocyte injury and glomerular disease, but may mediate further glomerular and tubular injury. Recently, albumin in the urinary space has been shown to injure both podocytes and neighboring PECs by enhancing apoptosis23, and by scavenging of retinoic acid 24

Podocyte death

Cells may die in a variety of ways including apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis and cell death associated with reduced autophagy. Increased podocyte apoptosis has been described in a range of experimental models of FSGS (reviewed in 25), however, it is notable that podocyte apoptosis is very rarely reported in human kidney biopsy specimens 26 and it remains unclear if this is a major mechanism leading to podocyte depletion in human disease.

Podocyte detachment

The podocyte cell body lies on the outside of the glomerular capillary in the urinary space. The podocyte foot processes wrap around and attach to the GBM predominantly through α3β1 and αvβ3 integrins, and α-dystroglycan / β-dystroglycan. Rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton following injury may lead to foot process effacement, and the cell can detach from the glomerular capillary and be swept away into the renal tubule.

Podocyte detachment has been well described in a range of experimental models, for example, α-actinin 4 deficient mice develop FSGS associated with reduced podocyte number, podocyturia and decreased podocyte adherence in vitro. 27 Activation of the podocyte integrin, αvβ3, by molecules such as the soluble urokinase receptor (suPAR), has recently been implicated in the development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. 10 When podocytes detach into the urinary space, they may traverse the tubule and be excreted in the urine (podocyturia). Notably, many of these cells are viable and can be grown in culture. Podocyturia occurs in a range of human glomerular diseases, including FSGS and diabetic kidney disease.

Podocyte depletion is required for the development of classic FSGS

Early studies in models of FSGS correlated the degree of podocyte depletion with the development and magnitude of FSGS. 28 The critical role of podocyte depletion in the development of glomerulosclerosis was subsequently confirmed in elegant studies by Wharram et al. 29 In a rat model with a site-specific transgene expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor only in podocytes, the administration of diphtheria toxin (dT) resulted in selective loss of podocytes with minimal inflammation. Higher doses of dT resulted in the loss of greater numbers of podocytes. This group was able to show that with the loss of less than 20% of podocytes, the glomerulus could recover, however, greater than 20% podocyte loss resulted in FSGS. The degree of scarring directly reflected the degree of podocyte depletion. Using a similar transgenic approach, Matsusaka et al expressed a toxin receptor for human CD25 in a subset of podocytes in mice. 30 Injection of a toxin that binds human CD25 resulted in podocyte depletion and the development of FSGS. Notably, in these chimeric mice, the initial podocyte injury could be propagated to neighboring uninvolved podocytes. 31 This concept of podocyte injury spreading to other podocytes in the glomerulus has now been shown in other models of podocyte depletion, and in some, may be ameliorated by angiotensin inhibition. has been described in the majority of experimental models of classic FSGS. In human studies, 32 A reduction in podocyte number podocyte depletion has also been reported. Similarly, in both type I and type II diabetic kidney disease, a reduction in podocyte number correlates with, and predicts, disease progression. 33,34 Taken together, podocyte depletion below a certain “threshold” is required for, and likely underlies, the initiation of classic FSGS in experimental and clinical studies.

Can podocyte number be restored?

If depletion of podocyte number plays a critical pathogenic role in the initiation and magnitude of classic FSGS, then we need to ask can we restore their number to reverse these disease processes. The adult podocyte is considered a terminally differentiated cell with a very limited ability to proliferate partly associated with constitutive expression of certain cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors. 25 Although podocytes may enter the cell cycle, and rarely undergo mitosis (nuclear division), they cannot complete cytokinesis (cell division), sometimes resulting in binucleated cells and/or mitotic catastrophe. 17 Given the critical role of the podocyte it may be considered surprising that the cell is unable to efficiently replicate.

If the podocyte number can be restored, the glomerulus may recover, however, in progressive FSGS, podocytes are not replenished, indeed, further injury may spread to other podocytes with progression of chronic kidney disease. Recent evidence has confirmed that in experimental models, a decrease in podocyte number can be restored despite the absence of podocyte proliferation. 35-37 This raises the question of how the podocyte number is reconstituted?

It has been suggested that there may be reservoirs of cells outside the glomerular tuft which can relocate to the GBM surface and differentiate into mature podocytes. 38 Bone marrow derived stem cells are not podocyte progenitors in two experimental models. 39 Some studies in humans have suggested that PECs may serve this podocyte progenitor role and repopulate the glomerulus following podocyte loss38,39, although this remains controversial, as similar paradigms do not exist in adult mice. 40 (see below). Cells of renin lineage have also been postulated to act as both podocyte and PEC progenitor cells. 41 Using genetic fate mapping studies, Pippin et al detected labeled cells of renin lineage which also expressed podocyte markers on the glomerular tuft after podocyte injury, suggesting that some juxtaglomerular cells may fulfill a podocyte progenitor role. Taken together, a literature is emerging that adult podocyte progenitors may exist, and their role will likely be better understood in the near future.

Role of the Parietal Epithelial Cell (PEC) in FSGS

Until recently, PECs were considered to have only a limited role in glomerular pathophysiology, but this almost forgotten epithelial cell is now recognized to play key roles in the development of FSGS, collapsing glomerulopathy and crescentic glomerulopathies (reviewed in42). The parietal epithelium consists of a monolayer of flat cells lining Bowman's basement membrane and is in direct contact with glomerular filtrate in the urinary space. During development, PECs and podocytes share a common lineage from metanephric mesenchyme. During transition from the S-shaped body to the capillary loop stage, some of these early epithelial cells differentiate in PECs, whereas others, under the master control of WT1, differentiate into podocytes. Adult PECs have a simplified cytoskeleton, and unlike adult podocytes, have the capacity of proliferate under physiological conditions. Published reports to date provide conflicting views on the role of PECs in FSGS, where they are potentially protective under certain circumstances, yet are injurious under others. We will review both perspectives.

Do PECs have a protective role in FSGS?

PECs represent a heterogeneous population of cells. Along the vascular pole of the glomerular tuft, PEC's on Bowman's basement membrane (BBM) are in continuity with podocytes on the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Indeed, within this region, glomerular epithelial transitional cells have been described, defined as cells which co-express both podocyte and PEC markers. These cells may migrate onto the glomerular tuft during growth and possibly following glomerular injury. Other cells located mostly at the tubular pole in normal human kidneys have features of renal progenitor cells (CD24, CD133 double positive) and may serve to replace lost podocytes or tubular epithelial cells. 43 Cell fate mapping studies during development 44 and in juvenile mice45 have confirmed that some podocytes on the glomerular tuft may be derived from PECs. Indeed, PECs may cross the urinary space directly to the glomerular tuft at sites other than the vascular pole. 46 However, this was not described in adult mice following podocyte ablation 40 and these recent studies are questioning the paradigm of PEC progenitor cells replenishing podocyte number in adults. 46 Recent evidence in a model of FSGS using genetically tagged podocytes suggests podocyte derived cells may newly express PEC markers following injury. 47 Notably, in a unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model, individual podocytes have also been directly visualized moving from the glomerular tuft to Bowman's basement membrane by multiphoton microscopy. 48 The current weight of evidence is leaning against the concept of new podocytes being recruited from the PEC population.

An intact parietal epithelial layer also functions to limit glomerular filtrate to the urinary space. Following podocyte injury and protein leak across the glomerular filtration barrier, tracer studies have suggested that the parietal epithelial layer may become more permeable to proteins, which has been speculated to have a pro-inflammatory effect. 49 Physical gaps in the parietal epithelium following the formation of cell bridges in early FSGS have also been associated with misdirected filtration into the periglomerular compartment. 3

PECs may be injurious in FSGS

Early morphological studies identified the formation of cellular bridges between PECs and bare GBM (i.e. areas devoid of overlying podocytes) as one of the earliest lesions in FSGS. 2,3 Djikman et al showed by serial sectioning that all glomeruli that form segmental sclerotic lesions initially develop an adhesion between the glomerular tuft and Bowman's capsule. 50 Immunostaining studies for cell specific markers in human FSGS have also demonstrated the presence of PECs within sclerotic areas. 51 Using PEC reporter mice, Smeets et al have shown that following podocyte injury, PECs on Bowman's basement membrane de novo express the marker CD44, and begin to deposit matrix, initially leading to thickening of Bowman's capsule. 52 They called the CD44 positive cells “activated PECs”. This Bowman's-type matrix (BC matrix) is also deposited in the cellular bridges leading to tuft adhesions. Most notably, using this lineage tracing technology, activated PECs were detected on the glomerular tuft, presumably having migrated across the tuft adhesion. In mice, activated PECs do not express stem cell or podocyte markers, and are considered to have a detrimental rather than regenerative role, similar have shown to an exaggerated wound healing response. These CD44 positive PECs are only found in the sclerotic regions and not in the unaffected areas of the glomerular tuft. Using an antibody that identifies BC matrix, this type of matrix was found to be deposited on the outside of the GBM at the sites of the segmental glomerular lesions which co-localized with the activated PECs. In human FSGS, the same group demonstrated the presence of PECs on the glomerular tuft (identified by claudin-1 staining) which co-localized with CD44 and BC matrix. Similar observations have been reported in recurrent human FSGS post transplant. 53 Of note, the CD44 marker of activated PECS is barely expressed in human minimal change disease, and may prove a useful marker to differentiate these two disorders on human kidney biopsies. 53

Although there remains debate about whether the presence of PECs on the glomerular tuft is beneficial (replenishing podocyte number), or detrimental (matrix deposition), PECs are being increasingly recognized in the classic FSGS lesion. Notably, unregulated proliferation of PEC progenitors might also account for the pseudo-crescents found in collapsing FSGS, which is beyond the scope of this review.54

Contribution of other resident glomerular cells Mesangial Cells

A role for mesangial cell injury in FSGS has been greatly overshadowed in recent years by the studies of the podocyte and PEC in this disease. A large literature shows that mesangial expansion is a common component of the FSGS lesion. Mesangial hypercellularity in some studies has been considered to portend a worse prognosis. It is usually considered that mesangial injury is a secondary phenomenon, and in experimental podocyte depletion models, depletion of 10-20% of podocytes does produce reversible mesangial expansion without progressing to FSGS. The nature of the cross talk is uncertain, but podocyte depletion and capillary ballooning could conceivably induce mesangial stretch. FSGS lesions are also described in primary mesangial disorders such as IgA nephropathy and experimental anti-thy1.1 nephritis. In IgA nephropathy, the development of tuft adhesions may occur in glomeruli with little evidence of capillary loop injury and in the absence of renal dysfunction, arguing against nephron loss and glomerular hyperfiltration as the etiology. In IgA nephropathy, it remains unclear if there is an associated podocytopathy, or if mesangial injury per se can lead directly to podocyte injury. In the anti-thy1.1 model, mesangial injury may lead to loss of anchoring or structural support of the capillary loop followed by ballooning of capillary loop and subsequent tuft adhesion. 55

A more mechanistic role of mesangial injury in FSGS has recently been suggested. 56 It is recognized in a range of glomerulopathies that IgM staining by immunofluorescence may be detected in the mesangium and has often been attributed to non-specific trapping, however, the association of IgM with concurrent mesangial C3 and C4 staining suggests complement activation. Using three different strategies to deplete B cells in mice with adriamycin induced glomerulosclerosis, Strassheim et al where able to reduce mesangial IgM deposition which was associated with a recution in albuminuria and attenuated renal pathology. 56 These data highlight mesangial cell involvement in FSGS, and further studies are needed to better define their role in the pathogenesis and potential progression of this glomerular lesion.

Glomerular Endothelial Cells

The glomerular endothelial cell (GEN) is not typically considered to play a major role in the development of FSGS. At early stages, even in glomeruli with extensive foot process effacement, endothelial injury is not prominent. However, at later stages of disease, often associated with hyalinosis, foam cell infiltration and sclerosis, endothelial injury or loss becomes more obvious, but is usually considered a secondary phenomenon. The mechanisms leading to endothelial injury in FSGS are not well defined. The podocyte is the main source for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) within the glomerulus which can cross the GBM and bind to receptors on GENs acting as a pro-survival and differentiation factor. Loss of podocyte derived VEGF following injury or in genetically modified mice leads to endothelial injury.57 Endothelial derived factors may also contribute to podocyte injury. Protein C is activated on the endothelial cell surface by thrombomodulin. Reductions in activated protein C enhance proteinuria and promote podocyte apoptosis through epigenetic regulation of podocyte oxidative stress. 58,59 It should also be recognized that diseases that cause primary GEN injury such as thrombotic microangiopathy or ANCA associated vasculitis can lead to segmental thrombosis or glomerular injury with the development of fibrotic segmental lesions with features that fulfill the criteria for FSGS. This serves to highlight that FSGS is a morphological pattern of injury that can be derived from a diverse range of initiating insults and on different glomerular cell types.

Understanding the pathogenesis of FSGS might assist in future therapeutic strategies

Current therapies for FSGS are discussed by Radhakrishnan, and Gipson, in this issue, and include a variety of immunosuppressive agents. Noteworthy is that these agents, and the standard of care use of RAAS inhibitors, also have direct (“pleotropic”) effects on podocytes that likely modulate their response to injury, and also assist with enhancing repair. Less well understood is the role of known therapeutic agents on PECs, mesangial cells and other cells in FSGS. Clearly, when considering therapy from a pathogenesis viewpoint, one can readily appreciate that several cells may need to be targeted, and likely at different stages of FSGS.

Summary

Recent molecular studies have largely confirmed the features described in the early morphological studies of FSGS. The traditional view of the pathogenesis of most forms of FSGS is that the initial injury is at the level of podocytes. This is best exemplified in the classic form of FSGS, whether primary or secondary in nature. The podocyte depletion paradigm has held center stage in the pathogenesis of classic FSGS for decades. While this is still likely correct as the inciting or early phases of the disease, recent studies have also implicated PECs in the pathogenesis of FSGS, and even more recent studies have begun to shed light on mesangial cells. Taken together, our view is that the pathogenesis of FSGS is a complex interplay involving several resident cell types, which may be involved over the course of disease. While these possibilities pose a huge challenge for currently used therapeutic interventions, a better understanding of the pathogenesis of FSGS will likely lead to the identification and perhaps development of new therapeutic targets.

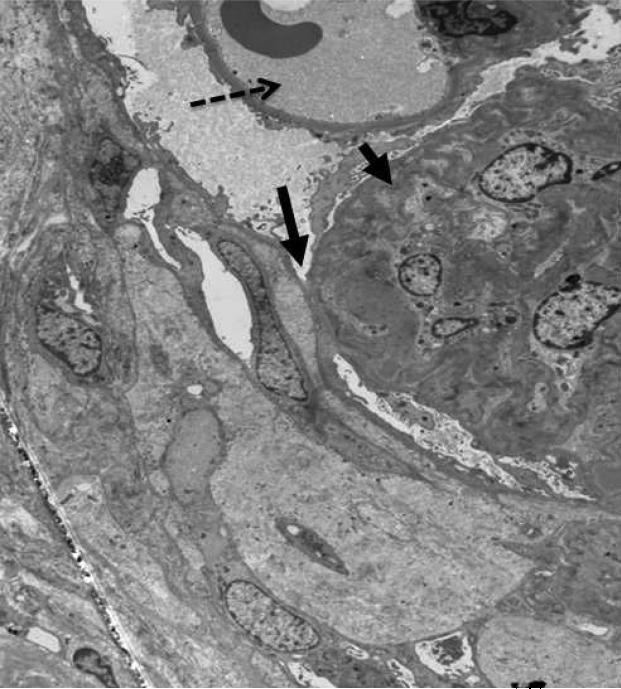

Figure 3a. FSGS lesion.

Electron micrograph. Unaffected open capillary loop containing red blood cell (dotted arrow). Tuft adhesion of glomerular basement membrane to Bowman's capsule (long arrow) with collapse and obliteration of capillary loop (short arrow).

Figure 3b. FSGS lesion.

Higher power electron micrograph shows evidence of hyaline (trapped plasma proteins) and fibrillar collagen within collapsed loops associated with obliteration of capillary lumen.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Cynthia Nast, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA, for supplying the light microscopy images and Dr Behzad Najafian, Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA for supplying the electron micrographs.

Abbreviations

- BC

Bowman's capsule

- FSGS

focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- GBM

glomerular basement membrane

- PEC

parietal epithelial cell

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest or financial disclosures

Contributor Information

J. Ashley Jefferson, Division of Nephrology University of Washington Box 356521 1959 NE Pacific Street Seattle, WA 98195.

Stuart J. Shankland, Division of Nephrology University of Washington Box 356521 1959 NE Pacific Street Seattle, WA 98195; Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA..

References

- 1.D'Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, et al. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368–382. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriz W, Elger M, Nagata M, et al. The role of podocytes in the development of glomerular TE sclerosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 1994;45:S64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeHir M, Kriz W. New insights into structural patterns encountered in glomerulosclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:184–191. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3280c8eed3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verani RR, Hawkins EP. Recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. A pathological study of the early lesion. Am J Nephrol. 1986;6:263–270. doi: 10.1159/000167173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rood IM, Deegens JK, Wetzels JF. Genetic causes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: implications for clinical practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:882–890. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183–2196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollak MR, Genovese G, Friedman DJ. APOL1 and kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:179–182. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835012ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy ET, Sharma M, Savin VJ. Circulating permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic AC syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2115–2121. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03800609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei C, Moller CC, Altintas MM, et al. Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med. 2008;14:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:952–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson JA, Alpers CE. Glomerular disease: ‘suPAR’-exciting times for FSGS. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:127–128. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner BM. Nephron adaptation to renal injury or ablation. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:F324–337. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.249.3.F324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kretzler M, Koeppen-Hagemann I, Kriz W. Podocyte damage is a critical step in the development of glomerulosclerosis in the uninephrectomised-desoxycorticosterone hypertensive rat. Virchows Arch. 1994;425:181–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00230355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durvasula RV, Petermann AT, Hiromura K, et al. Activation of a local tissue angiotensin system in podocytes by mechanical strain. Kidney Int. 2004;65:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann S, Podlich D, Hahnel B, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor overexpression in podocytes induces glomerulosclerosis in transgenic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1475–1487. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000127988.42710.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsusaka T, Asano T, Niimura F, et al. Angiotensin receptor blocker protection against R podocyte-induced sclerosis is podocyte angiotensin II type 1 receptor-independent. Hypertension. 2010;55:967–973. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulay SR, Thomasova D, Ryu M, et al. Podocyte loss involves MDM2-driven mitotic catastrophe. J Pathol. 2013;230:322–335. doi: 10.1002/path.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda A, Chowdhury MA, Venkatareddy MP, et al. Growth-dependent podocyte failure causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1351–1363. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimanyi MA, Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, et al. Nephron number and individual glomerular volumes in male Caucasian and African American subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2428–2433. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Ellis MJ, Gomez JA, et al. Mechanisms of the proteinuria induced by Rho GTPases. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1075–1085. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akilesh S, Suleiman H, Yu H, et al. Arhgap24 inactivates Rac1 in mouse podocytes, and a mutant form is associated with familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4127–4137. doi: 10.1172/JCI46458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gee HY, Saisawat P, Ashraf S, et al. ARHGDIA mutations cause nephrotic syndrome via defective RHO GTPase signaling. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3243–3253. doi: 10.1172/JCI69134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang AM, Ohse T, Krofft RD, et al. Albumin-induced apoptosis of glomerular parietal epithelial cells is modulated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1330–1343. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peired A, Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, et al. Proteinuria impairs podocyte regeneration by sequestering retinoic Acid. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1756–1768. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012090950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shankland SJ. The podocyte's response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. E Kidney Int. 2006;69:2131–2147. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kriz W, Shirato I, Nagata M, et al. The podocyte's response to stress: the enigma of foot C AC process effacement. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F333–347. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00478.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dandapani SV, Sugimoto H, Matthews BD, et al. Alpha-actinin-4 is required for normal podocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:467–477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YH, Goyal M, Kurnit D, et al. Podocyte depletion and glomerulosclerosis have a direct relationship in the PAN-treated rat. Kidney Int. 2001;60:957–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wharram BL, Goyal M, Wiggins JE, et al. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2941–2952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsusaka T, Xin J, Niwa S, et al. Genetic engineering of glomerular sclerosis in the mouse via control of onset and severity of podocyte-specific injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1013–1023. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsusaka T, Sandgren E, Shintani A, et al. Podocyte injury damages other podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1275–1285. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010090963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukuda A, Wickman LT, Venkatareddy MP, et al. Angiotensin II-dependent persistent podocyte loss from destabilized glomeruli causes progression of end stage kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81:40–55. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer TW, Bennett PH, Nelson RG. Podocyte number predicts long-term urinary albumin T excretion in Pima Indians with Type II diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1341–1344. doi: 10.1007/s001250051447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steffes MW, Schmidt D, McCrery R, et al. Glomerular cell number in normal subjects and in type 1 diabetic patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59:2104–2113. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benigni A, Morigi M, Rizzo P, et al. Inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme promotes renal repair by limiting progenitor cell proliferation and restoring the glomerular C architecture. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macconi D, Sangalli F, Bonomelli M, et al. Podocyte repopulation contributes to regression of glomerular injury induced by ACE inhibition. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:797–807. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichaiwong W, Hudkins KL, Wietecha T, et al. Reversibility of structural and functional damage in a model of advanced diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1088–1102. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grahammer F, Wanner N, Huber TB. Podocyte regeneration: who can become a podocyte? Am J Pathol. 2013;183:333–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer-Schwesinger C, Lange C, Brocker V, et al. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells do not contribute to podocyte turnover in the puromycin aminoglycoside and renal ablation models in rats. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berger K, Schulte K, Boor P, et al. The Regenerative Potential of Parietal Epithelial Cells in Adult Mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pippin JW, Sparks MA, Glenn ST, et al. Cells of renin lineage are progenitors of podocytes and parietal epithelial cells in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:542–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shankland SJ, Anders HJ, Romagnani P. Glomerular parietal epithelial cells in kidney PTE physiology, pathology, and repair. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013 doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835fefd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ronconi E, Sagrinati C, Angelotti ML, et al. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanner N, Hartleben B, Herbach N, et al. Unraveling the Role of Podocyte Turnover in Glomerular Aging and Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Appel D, Kershaw DB, Smeets B, et al. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulte K, Berger K, Boor P, et al. Origin of parietal podocytes in atubular glomeruli mapped by lineage tracing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:129–141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013040376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakamoto K, Ueno T, Kobayashi N, et al. The direction and role of phenotypic transition between podocytes and parietal epithelial cells in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F98–F104. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00228.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hackl MJ, Burford JL, Villanueva K, et al. Tracking the fate of glomerular epithelial cells in vivo using serial multiphoton imaging in new mouse models with fluorescent lineage tags. Nat Med. 2013;19:1661–1666. doi: 10.1038/nm.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohse T, Chang AM, Pippin JW, et al. A new function for parietal epithelial cells: a second glomerular barrier. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1566–1574. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00214.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dijkman H, Smeets B, van der Laak J, et al. The parietal epithelial cell is crucially involved in human idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1562–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohtaka A, Ootaka T, Sato H, et al. Significance of early phenotypic change of glomerular podocytes detected by Pax2 in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:475–485. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.31391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smeets B, Kuppe C, Sicking EM, et al. Parietal epithelial cells participate in the formation of sclerotic lesions in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1262–1274. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010090970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fatima H, Moeller MJ, Smeets B, et al. Parietal epithelial cell activation marker in early CR recurrence of FSGS in the transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1852–1858. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10571011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smeets B, Uhlig S, Fuss A, et al. Tracing the origin of glomerular extracapillary lesions from parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2604–2615. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kriz W, Hahnel B, Hosser H, et al. Pathways to recovery and loss of nephrons in anti-Thy-1 nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1904–1926. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070073.79690.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strassheim D, Renner B, Panzer S, et al. IgM contributes to glomerular injury in FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:393–406. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1129–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bock F, Shahzad K, Wang H, et al. Activated protein C ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by epigenetically inhibiting the redox enzyme p66Shc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:648–653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218667110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isermann B, Vinnikov IA, Madhusudhan T, et al. Activated protein C protects against diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting endothelial and podocyte apoptosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1349–1358. doi: 10.1038/nm1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]