Abstract

Lacrimal outflow can be compromised by anatomical obstructions or stenoses (nonfunctional epiphora) or by defective lacrimal “pump” function (functional epiphora). Although classic imaging modalities, such as X-ray dacryocystography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging can effectively evaluate the former, their success is much less in the evaluation of the latter. This is largely due to the fact that forced diagnostic injection of fluid into the canalicular system can overcome partial obstruction sites. On the other hand, lacrimal scintigraphy mimicks “physiological” lacrimal outflow, being performed under pressure gradients present in everyday life. This is why it is considered more suitable for the study of functional epiphora. Furthermore, quantitative lacrimal scintigraphy (with time-activity curves) enables the accurate measurement of lacrimal clearance from the conjunctival fornices and may be used to study the physiology of the lacrimal “pump.” Data obtained from the scintigraphic study of lacrimal outflow may be used to design more effective procedures in the management of functional and nonfunctional epiphora. This is a review article, based on a literature search with emphasis on recent publications and on those supporting interdisciplinary cooperation between ophthalmology and nuclear medicine.

Keywords: Canalicular stenosis, dacryocystorhinostomy, epiphora, lacrimal pump, lacrimal scintigraphy, nasolacrimal duct stenosis

Introduction

Epiphora is a bothersome clinical situation, which may necessitate significant diagnostic effort to be fully evaluated. The physician addressing this condition may rely on history or clinical signs to determine the causes, which may include lacrimal hypersecretion, canalicular (presac) obstructions or stenoses, nasolacrimal (postsac) obstructions or stenoses, or may even be functional (nonanatomic), due to a “lacrimal pump” failure. However, clinical information per se may not be enough and in that case, imaging modalities, such as lacrimal scintigraphy, may be required. The present review aims at presenting the role and advantages of lacrimal scintigraphy as a diagnostic tool for epiphora.

Clinical Background

Epiphora is one of the most common ophthalmic symptoms.[1,2] Although, it can be produced by lacrimal hyper-secretion (due to inflammatory or irritative conditions)[3] or to eyelid malpositions (such as ectropion or entropion),[4,5] it is usually associated with defective lacrimal outflow.[1,2] The anatomical lacrimal outflow route includes the upper and lower lacrimal puncta, upper and lower canaliculi, common canaliculus, lacrimal sac (LS) and nasolacrimal duct [Figure 1].[1,2] Various valve-like formations are located along this route, especially at the common canliculus and lower end of the nasolacrimal duct (Rosenmuller and Hasner valves, respectively).[1,2] Anatomical alterations, such as stenoses or obstructions, can develop at any point along this route and may compromise lacrimal drainage.[1,2] However, apart from any anatomical changes, lacrimal outflow may also be affected by functional causes, such as a defective lacrimal “pump” mechanism.[6,7,8]

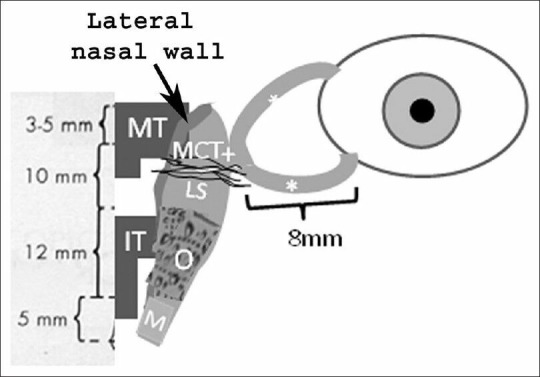

Figure 1.

Schematic anatomical presentation of the lacrimal drainage route, including the superior and inferior canaliculi (*), common canaliculus (+), lacrimal sac (LS), osseous (O) and membranous (M) parts of the nasolacrimal duct and middle and inferior turbinates (MT and IT, respectively). The anterior part of the medial canthal tendon (MCT), the lateral nasal wall and the mean lengths (mm) of the above mentioned structures are also shown

Epiphora may be watery (usually due to punctal or canalicular causes) or mucous (the so-called “sticky eye”).[1,2] The latter implies entrance of tears into the LS, where mucous is formed, and regurgitation back to the eyes through an obviously patent canalicular system.[1,2] In that case, the site of obstruction is, therefore, postsaccal. Mucopurulent secretions imply an associated infection (dacryocystitis). Although the type of secretions (watery or mucous) may generally point toward a specific site of obstruction (canalicular or postsaccal, respectively), the exact determination of the causes of epiphora may require a more detailed clinical examination.[9,10] This may include slit-lamp biomicroscopy to assess the patency and caliber of the lacrimal puncta, probing and irrigation of the canalicular system as well as fluorescein instillation to the conjunctival sac to assess drainage to the ipsilateral nasal cavity [Figures 2 and 3].[9,10] Treatment of watery or mucous epiphora due to postsaccal nasolacrimal obstruction is usually performed by dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR), that is, an anastomosis between the LS and nasal mucosa at the level of the middle nasal meatus.[11,12] DCR can be performed either transcutaneously (external DCR) or transnasally (endoscopic DCR).[13,14] However, in some cases, persistent epiphora is reported despite an anatomically patent drainage route (functional epiphora).[15] Imaging of the lacrimal outflow route by various modalities, such as lacrimal scintigraphy, may be required in such cases for an accurate decision-making concerning the causes of epiphora, for the study of potential associated pathophysiological mechanisms as well as for the selection of an appropriate surgical treatment.[6]

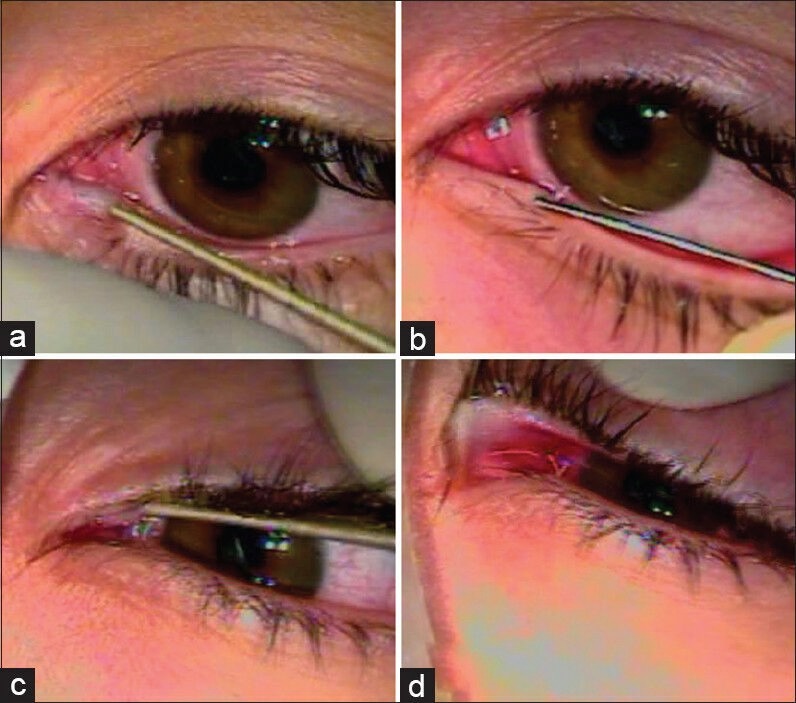

Figure 2.

Dilation of the inferior (a) and superior (c) lacrimal puncta and insertion of a nasolacrimal irrigation cannula(b and d, respectively)

Figure 3.

Classic dacryocystography, showing a patent system on the right side with descent of the radio-opaque agent to the nasal and oral cavities. On the contrary, the system to the left side is obstructed, with a block to the superior nasolacrimal duct

Methods

Data were obtained by literature search in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). Key words, including “lacrimal pump,” “scintigraphy,” “epiphora,” “canalicular,” “nasolacrimal duct” “stenosis,” “obstruction” and “DCR” were used. The articles obtained were examined based on publication date and relevance, with emphasis to recent work and work stressing the cooperation between ophthalmology and nuclear medicine.

Physiology of the lacrimal outflow

Lacrimal clearance (i.e., the elimination of tears from the conjunctival cul-de-sac) relies on several factors, such as gravity, capillary attraction forces, evaporation, absorption by the conjunctival surface, residual (Krebhiel) flow and the lacrimal “pump.”[1,9] Although some controversy exists concerning the exact mechanism of the latter, most studies agree that it relies on the action of the orbicularis oculi muscle, particularly its deeper part (Horner's muscle), which inserts on the LS.[16] According to Jones' theory, the contraction of Horner's muscle may cause expansion of the sac and creation of negative pressure resulting in tear suction.[1,2,17] On the contrary, Rosengren-Döane theory postulates that the elastic expansion of the lacrimal papillae upon opening of the eyelids sucks tears into the sac and the subsequent contraction of orbiculars oculi creates a positive pressure gradient that may drive tears along the nasolacrimal duct and into the nose.[1,2,17] Becker's theory combines elements from both Jones' and Rosengren-Döane theories, suggesting that an asymmetric movement of the superior (outer) over the inferior (inner) portion of the canaliculi drives tears into the canalicular system (simultaneous suction and compression).[1,2,17] Irrespective of the exact mechanism (positive or negative pressure gradients) the contraction of orbicularis oculi (blinking) as well as an adequate elastic tension of the eyelids (adequate eyelid-eyeball apposition) are considered critical in maintaining the “pump” mechanism.[8] The respiratory movements, cardiac circle and associated fluctuations in the pressure of vein plexuses surrounding the LS may also participate in the “pump” mechanism.[18] It is possible that tears travel in the form of boluses (rather than as a continuous flow) along the nasolacrimal duct, which could reflect the mode of pump activity (influences of blinking, respiration, or cardiac circle).[16]

Imaging modalities for the lacrimal outflow apparatus

Several methodologies have been previously used to delineate sites of stenosis or obstruction and to quantitatively assess lacrimal outflow.[6,8,15,19,20] Simple dacryocystography (performed by probing and injection or radio-opaque material into the canalicular system) may be adequate for the anatomical identification of stenotic sites, but suffers from the fact that forced injection overcomes partial obstruction or stenosis.[19,21] Computed tomography [Figure 4b] scans delineate accurately the bony structures surrounding the LS and nasolacrimal duct and may be adequate for specific lesions such as osseous tumors (osteomas) or lacrimal stones, but lacks specificity for soft tissue structures.[19] Ultrasonography can be used to produce images of the LS and even show the flow of tears through the anastomotic ostium following DCR.[20] However, the ultrasonic probe exerts pressure on the medial canthal area (potentially affecting pressure gradients created under physiological conditions), whereas filling of the sac with saline or viscoelastic substances may be required to produce sac images.[20,22] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers excellent delineation of soft tissue structures and the borders between soft tissue and bone as well as identification of the water content in various tissues [Figure 4a]. Various MRI-based dacryocystography techniques have been described so far, including LS volume measurement during blinking,[23] dynamic MRI during blinking,[16] three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient-recalled MRI dacryocystography[24] or the measurement of the water content at specific regions of interests (ROIs) along the lacrimal drainage route following DCR before and after blinking.[8,15] The latter has shown that the lacrimal “pump” remains active even following DCR.[8,15] Although dynamic studies of lacrimal drainage (such as the determination of the water content at the ipsilateral nasal cavity before and after blinking) are theoretically possible with MRI, they are relatively difficult to perform, compared with other dynamic studies, such as lacrimal scintigraphy.[6,21] Furthermore, they should ideally be performed with topographical registration of specific sections to allow for comparisons between images taken on different MRI sessions.[25]

Figure 4.

Delineation of nasolacrimal ducts by T-1 oriented MRI (a) and CT (b). The ducts are shown by white arrows in the MRI sections and by asterisks in the CT sections

Lacrimal scintigraphy overview

Lacrimal scintigraphy has been extensively used in the study of lacrimal drainage, facilitating the definite diagnosis of obstructions and stenosis of the lacrimal drainage system with little stress to the patient.[6,26,27,28] The fact that it is not performed under manual injection pressure (as in the case of X-ray dacryocystography) implies that scintigraphic imaging reflects “physiological” drainage conditions.[6] Lacrimal scintigraphies can be performed with a variety of gamma cameras, such as the Siemens Digitrac 3700 Orbiter Spect Gamma Camera (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), with pin-hole collimator. 50 μCi of Tc-99 m pertechnetate (in 50 μl normal saline) are usually instilled into each conjunctival fornix.[6] The patient stands upright in front of the gamma camera, blinking normally. Sequential images (1 frame/30 s for 10 min in specific matrix sizes, such as 64 × 64 pixels) as well as planar-static images at specific intervals are taken.[6] There are large variations in transit time, even in normal asymptomatic individuals, as well as differences in the delay at specific points (“presac,” “preduct” delay or “intraduct” delay).[6,21,27,29] However, a time-frame of 0-10 min (based on a broad approximate agreement concerning the expected timing of stages in the lacrimal scintigram), is usually adequate.[21] Planar static images [Figure 5] may be taken at specific intervals along this time-frame (such as 2.5 min, 5 min, 7.5 min, and 10 min, as previously described).[6]

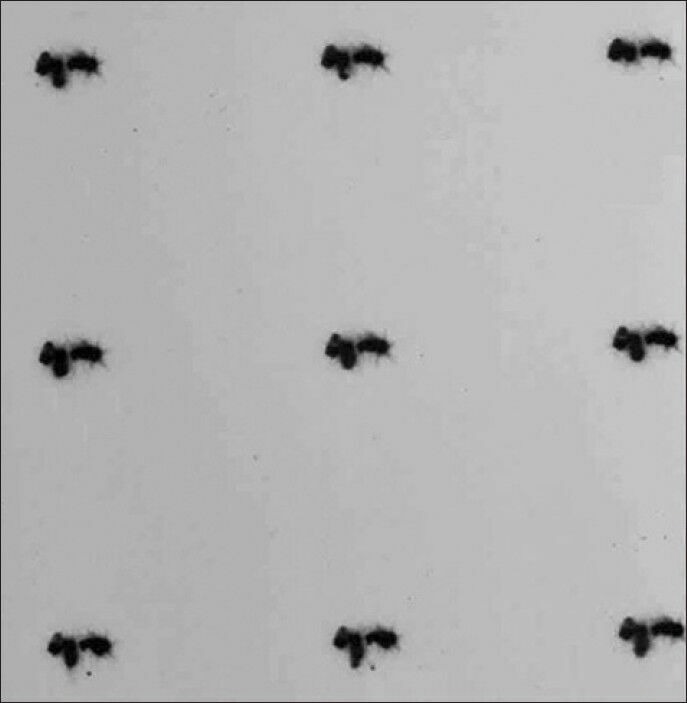

Figure 5.

Sequential planar-static lacrimal scintigrams, showing patent right side but obstructed left side

Quantitative Lacrimal Scintigraphy

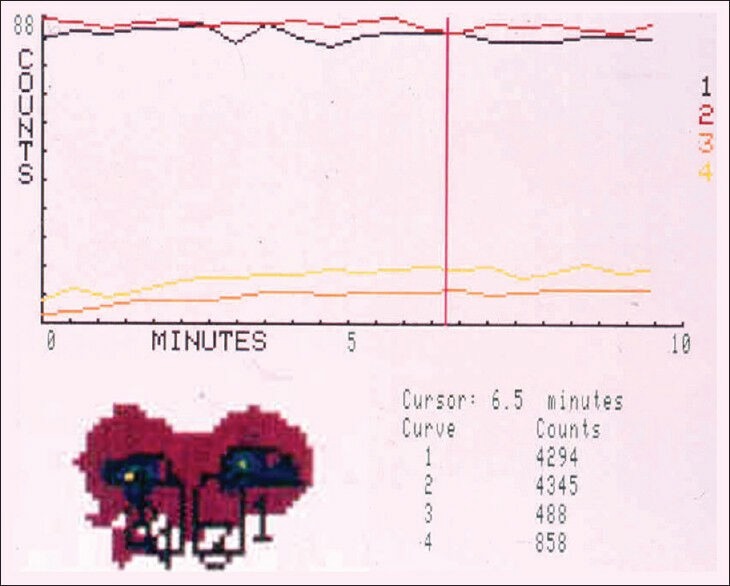

Lacrimal scintigraphy also enables the quantitative assessment of tear drainage rate.[6,27] For this purpose, the number of counts from specific ROIs with equal pixel sizes, such as right and left conjunctival area and right and left nasolacrimal duct area is recorded.[6,27] The total number of counts (summation of counts over conjunctival and ipsilateral nasolacrimal ROIs) is calculated to confirm the preservation of radioactive material (i.e., lack of potential overflow on the cheek).[6] Time-activity curves are constructed [Figures 6 and 7] and the conjunctival lacrimal clearance (CLC, percentage of reduction in the number of counts at the conjunctival ROIs, compared with the initial number of counts) at specific time intervals (such as 2.5 min, 5 min, 7.5 min, and 10 min) following the instillation of the radioactive material is calculated.[6]

Figure 6.

Quantitative lacrimal scintigram showing bilateral complete obstructions. Note that the number of counts remains low for the nasal ROIs (3 and 4) and high for the ocular ROIs (1 and 2) throughout the 10min of recording

Figure 7.

Quantitative lacrimal scintigram showing a patent system on the right side (curves 1 and 3) and a partially obstructed (stenosed) system on the left side (curves 2 and 4)

Lacrimal “Pump” Function: Potential Diagnostic and Treatment Options

Watery epiphora can significantly affect the quality of life of patients and may be more difficult to treat than mucopurulent discharge.[15] It often occurs despite the lack of obvious causative factors, such as eyelid malpositions, trichiasis, ocular surface inflammations and any stenosis at the lacrimal outflow route.[11,15] In such cases, a defective lacrimal “pump” function [Figure 8] is usually the underlying condition.[15] Interestingly, watery epiphora can occur even following a successful DCR, which is particularly bothersome since it compromises the results of an anatomically successful procedure (i.e. a procedure that has unified anatomically the LS and middle nasal meatus compartments).[7] In these cases, a decreased tear flow rate through the DCR ostium has been documented.[18] According to previous studies employing lacrimal scintigraphy, the assessment of CLC at specific time intervals (such as 2.5 min and 5 min following the instillation of radioactive material into the conjunctival cul-de-sac) may be used to decide treatment strategies for functional acquired epiphora,[6] such as the horizontal shortening of the lower eyelid to augment the action of the lacrimal “pump” (since lower eyelid laxity has been associated with decrease lacrimal pump function[6]). Further research would be required to determine the exact role that quantitative lacrimal scintigraphy could play in the therapeutic decision making for functional epiphora, especially in cases following and anatomically successful DCR.

Figure 8.

Presentation of the lacrimal pump mechanism according to 2 different theories, i.e. Rosengren-Döane (a and c) and Jones (b and d). In the case of Rosengren-Döane, tears are sucked into the canalicular system upon the opening of the eyelids due to the elastic expansion of the lacrimal papillae (a) and expulsed along the nasolacrimal duct upon the closure of the eyelids due to sac compression (c) In the case of Jones' theory, tears are expulsed along the duct upon the opening of the eyelids (b) and are sucked into the sac when the orbicularis oculi contracts (d)

Conclusions

Lacrimal scintigraphy evaluates the lacrimal drainage apparatus in a “physiological” manner, that is, with pressure gradients present in every-day life; thus, it may be more suitable for the study of functional epiphora than other imaging modalities. Furthermore, quantitative scintigraphic studies for the accurate calculation of the lacrimal clearance are possible and can be employed in routine clinical practice. Recent evidence from scintigraphic and MRI studies stress the role of the lacrimal “pump” in lacrimal drainage and imply that the “pump” mechanism should be enhanced when attempting to correct functional acquired epiphora. This area requires the inter-disciplinary co-operation between ophthalmologists and nuclear medicine specialists, since the interpretation of results should be performed from both view-points. Future research, in this area may also include the application of quantitative scintigraphy for the study of LS function in tear drainage (i.e., its role as a component of the lacrimal pump).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wesley RE. Lacrimal disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1994;5:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurwitz JJ, Cooper PR, McRae DL, Chenoweith DR. The investigation of epiphora. Can J Ophthalmol. 1977;12:196–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudouin C. A new approach for better comprehension of diseases of the ocular surface. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30:239–46. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(07)89584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vick VL, Holds JB, Hartstein ME, Massry GG. Tarsal strip procedure for the correction of tearing. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:37–9. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000103005.81708.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkat CN, Lemke BN. Acquired lax eyelid syndrome: An unrecognized cause of the chronically irritated eye. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:52–8. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000150360.84043.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detorakis ET, Zissimopoulos A, Katernellis G, Drakonaki EE, Ganasouli DL, Kozobolis VP. Lower eyelid laxity in functional acquired epiphora: Evaluation with quantitative scintigraphy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:25–9. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000192652.17317.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker BB. Tricompartment model of the lacrimal pump mechanism. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31839-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detorakis ET, Drakonaki EE, Bizakis I, Papadaki E, Tsilimbaris MK, Pallikaris IG. MRI evaluation of lacrimal drainage after external and endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:289–92. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181ac5320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzek JP, Ching AS, Hoang TA, Dure-Smith P, Llaurado JG, Yau DC, et al. Clinical and radiologic lacrimal testing in patients with epiphora. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1875–81. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuthbertson FM, Webber S. Assessment of functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction - A survey of ophthalmologists in the southwest. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:20–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Donnell B, Shah R. Dacryocystorhinostomy for epiphora in the presence of a patent lacrimal system. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2001;29:27–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurwitz JJ. Lacrimal surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1990;1:521–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenk J, Karatzanis AD, Psychogios G, Franzke K, Koch M, Hornung J, et al. Long-term results of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1733–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saratziotis A, Emanuelli E, Gouveris H, Babighian G. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction: Creating a window with a drill without use of mucosal flaps. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;31:1–4. doi: 10.1080/00016480802495396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detorakis ET, Drakonaki E, Papadaki E, Pallikaris IG, Tsilimbaris MK. Watery eye following patent external DCR: An MR dacryocystography study. Orbit. 2010;29:239–43. doi: 10.3109/01676831003660697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amrith S, Goh PS, Wang SC. Tear flow dynamics in the human nasolacrimal ducts - A pilot study using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:127–31. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-1045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nesi FA, Waltz KL, Vega J. Basic principles of ophthalmic plastic surgery. In: Nesi FA, Lisman RD, Levine MR, editors. Smith's Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nik NA, Hurwitz JJ, Sang HC. Mechanism of tear flow after dacryocystorhinostomy and Jones' tube surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1643–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031333020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manfrè L, de Maria M, Todaro E, Mangiameli A, Ponte F, Lagalla R. MR dacryocystography: Comparison with dacryocystography and CT dacryocystography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1145–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavlidis M, Stupp T, Grenzebach U, Busse H, Thanos S. Ultrasonic visualization of the effect of blinking on the lacrimal pump mechanism. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:228–34. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-1033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wearne MJ, Pitts J, Frank J, Rose GE. Comparison of dacryocystography and lacrimal scintigraphy in the diagnosis of functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1032–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.9.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ezra E, Restori M, Mannor GE, Rose GE. Ultrasonic assessment of rhinostomy size following external dacryocystorhinostomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:786–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.7.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amrith S, Goh PS, Wang SC. Lacrimal sac volume measurement during eyelid closure and opening. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35:135–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karagülle T, Erden A, Erden I, Zilelioglu G. Nasolacrimal system: Evaluation with gadolinium-enhanced MR dacryocystography with a three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient-recalled technique. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2343–8. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curati WL, Williams EJ, Oatridge A, Hajnal JV, Saeed N, Bydder GM. Use of subvoxel registration and subtraction to improve demonstration of contrast enhancement in MRI of the brain. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:717–23. doi: 10.1007/s002340050335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossomondo RM, Carlton WH, Trueblood JH, Thomas RP. A new method of evaluating lacrimal drainage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972;88:523–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000030525010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurwitz JJ, Maisey MN, Welham RA. Quantitative lacrimal scintillography. I. Method and physiological application. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59:308–12. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.6.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanna IT, MacEwen CJ, Kennedy N. Lacrimal scintigraphy in the diagnosis of epiphora. Nucl Med Commun. 1992;13:416–20. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199206000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chavis RM, Welham RA, Maisey MN. Quantitative lacrimal scintillography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2066–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060454013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]