Abstract

Introduction

Angiotensin (Ang)-(1-7) is a recently identified vasoprotective heptapeptide and it appears to activate the reparative functions of bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells (BMPCs).

Aim

This study evaluated the effect of Ang-(1-7) in the angiogenic function of cavernosum in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and delineated the role of BMPCs in this protective function.

Methods

T1D was induced by streptozotocin in mice and mice with 20-24 weeks of diabetes were used for the study. Ang-(1-7) was administered subcutaneously by using osmotic pumps. Cavernosa, and BMPCs from peripheral blood and bone marrow were evaluated in different assay systems.

Main outcome measures

Angiogenic function was determined by endothelial tube formation in matrigel assay. Circulating BMPCs were enumerated by flow cytometry and proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation. Cell-free supernatant of BMPCs were collected and tested for paracrine angiogenic effect. Expression of angiogenic factors in BMPCs and cavernosa were determined by real-time PCR.

Results

Ang-(1-7) (100 nM) stimulated angiogenesis in mouse cavernosum that was partially inhibited by Mas1 receptor antagonist, A779 (10 μM) (P<0.05). In cavernosa of T1D, the angiogenic responses to Ang-(1-7) (P<0.005) and VEGF (100 nM) (P<0.03) were diminished. Ang-(1-7) treatment for four weeks reversed T1D-induced decrease in the VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Ang-(1-7) treatment increased the circulating number of BMPCs and proliferation that were decreased in T1D (P<0.02). Paracrine angiogenic function of BMPCs was reduced in diabetic BMPCs, which was reversed by Ang-(1-7). In diabetic BMPCs, SDF and angiopoietin-1 were up-regulated by Ang-(1-7) and in cavernosum, VEGFR1, Tie-2 and SDF were up-regulated and angiopoietin-2 was down-regulated.

Conclusions

Ang-(1-7) stimulates angiogenic function of cavernosum in diabetes via its stimulating effects on both cavernosal microvasculature and BMPCs.

Keywords: Diabetes, Cavernosum, Angiogenesis, Angiotensin-(1-7), Bone marrow cells, Paracrine, Angiogenic factors, Vasoprotective

Introduction

Long-term diabetes is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease including erectile dysfunction (ED). Prevalence of ED among diabetic individuals ranges from 35-70% [1,2]. Dysfunction of cavernosal endothelium, characterized by impaired vasodilatory and angiogenic functions, largely contributes to erectile dysfunction [3,4].

Angiotensin-(1-7) (Ang-(1-7) is a heptapeptide produced by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 from the substrate angiotensin II [5,6]. Ang-(1-7) produces its physiological effects by activating Mas receptor [7]. Accumulating evidence supports the notion that activation of ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas axis is cardiovascular protective in several models of cardiovascular disease [8]. Recent studies provide compelling evidence for the protective effects of Ang-(1-7) in diabetic erectile dysfunction. Ang-(1-7) or Mas receptor activation stimulates erectile response in rodents [9,10] and Ang-(1-7) treatment reversed the cavernosal dysfunction induced by diabetes and hyperlipidemia [11-13].

Bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells (BMPCs) have been shown to play a key role in the cardiovascular homeostasis [14]. Re-endothelialization of cardiovascular tissues by different population of BMPCs is now being considered as a promising approach for the treatment of cardiovascular complications [15,16]. The therapeutic potential of cell-based therapies for the treatment of ED or cavernosal injury has recently been shown in experimental studies using muscle- or adipose-derived stem cells [17,18]. In mice, lineage-negative (Lin-) cells expressing either Sca-1 or cKit or both are well known as hematopoietic cells, possess vasoprotective/regenerative functions [19,20]. Mobilization of BMPCs from BM in response to vascular injury or endothelial damage is an essential event in the endogenous vascular repair process [21,22]. BMPCs are recruited to the areas of endothelial damage by the tissue-derived hypoxia-regulated factors such as stromal derived factor-1 (SDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [23]. Recent studies indicate that in diabetes the dysfunction of vasoprotective BMPCs triggers the onset of diabetic complications [24]. Recruitment of BMPCs to the areas of vascular injury and the reparative functions are impaired in diabetes [25]. Proliferation and migration of diabetic BMPCs to hypoxia-regulated factors are impaired [26,27], and cannot induce re-endothelialization or support vascular regeneration in the areas of ischemia [27,28].

The involvement of BMPCs in the cardiovascular protection by Ang-(1-7) has recently been investigated. Ang-(1-7) expression enhanced in vitro and in vivo vasoreparative functions of dysfunctional CD34+ cells derived from individuals with diabetes [29]. In this study we have evaluated the beneficial effects of Ang-(1-7) in the angiogenic function of corpus cavernosum in diabetes and tested the hypothesis that BMPCs participate in the protective functions of Ang-(1-7). This study is performed in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ). It is important to note that while this model produces erectile dysfunction due to hyperglycemia, it would not ideally represent the current clinical scenario of diabetes, which is type 2 characterized by hyperinsulinemia and metabolic syndrome in addition to hyperglycemia.

Methods

All the animal procedures were carried in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of North Dakota State University. Male C57Bl/6 mice (Harlan laboratories) at approximately 6 weeks of age were acclimatized for up to two weeks before experimentation. Type 1 diabetes, was induced by STZ and mice with blood glucose of 300 - 400 mg/dl were assigned to treatment groups at 20±2 weeks of diabetes. A total of 32 mice were used in the study.

For tissue collection, mice were killed by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia immediately followed by thoracotomy. The penis was removed from each animal by separating the crura at the point of adhesion to the lower pubic bone, and the corpus cavernosa were then excised. The central penile artery was removed and the cavernosal strips were either used for matrigel angiogenesis assay or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen followed by preservation at -80°C, for molecular expression studies.

Ang-(1-7) was administered by continuous subcutaneous infusion by using osmotic pumps (Alzet) at a rate of 1 μg/Kg/minute for four weeks. Angiogenesis assays were carried out in matrigel and the tube formation was quantified by measuring tubular length using ImageJ Software (NIH). Circulating BMPCs, Lin- or Lin-Sca-1+ (LS) cells were enumerated in peripheral blood or isolated from bone marrow for in vitro or ex vivo studies including proliferation assay, preparation of conditioned media and gene expression studies.

Conditioned media was obtained by plating LS cells in endothelial basal medium (EBM2, Lonza), at a density of 2×104 cells/150 microL/well in a U-bottom 96-well plate. After 18-20 hours, cell suspension was collected and cell-free medium was obtained by centrifuging at 150 g for 10 minutes. Conditioned medium was preserved at -80°C until further use. When required, medium was thawed at 4-8°C and used in the angiogenesis assay.

Cell proliferation was evaluated by determining BrdU incorporation (Cell Proliferation ELISA; Roche Bioscience). Assay was carried out using 1×104 cells/well in 100 ml of the assay buffer and BrdU was added after 18 hours. Following 24 hours of incubation with BrdU, incorporation into cells was assayed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell proliferation in a treated cell sample was expressed relative to the proliferation in a negative control i.e. cells treated with 10 μM mitomycin C, an inhibitor of proliferation.

See the supplement for detailed methods for cell preparation, flow cytometry, RNA isolation for real-time PCR and for the list of primers used for PCR amplification of different genes.

Statistics

Results were expressed as Mean ± SEM and ‘n’ represents the number of mice used. Results were compared by using unpaired Student’s ‘t’-test or one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison, using the program GraphPad Prism (Prism). P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ang-(1-7) stimulates angiogenic response in cavernosum of nondiabetic and diabetic mice

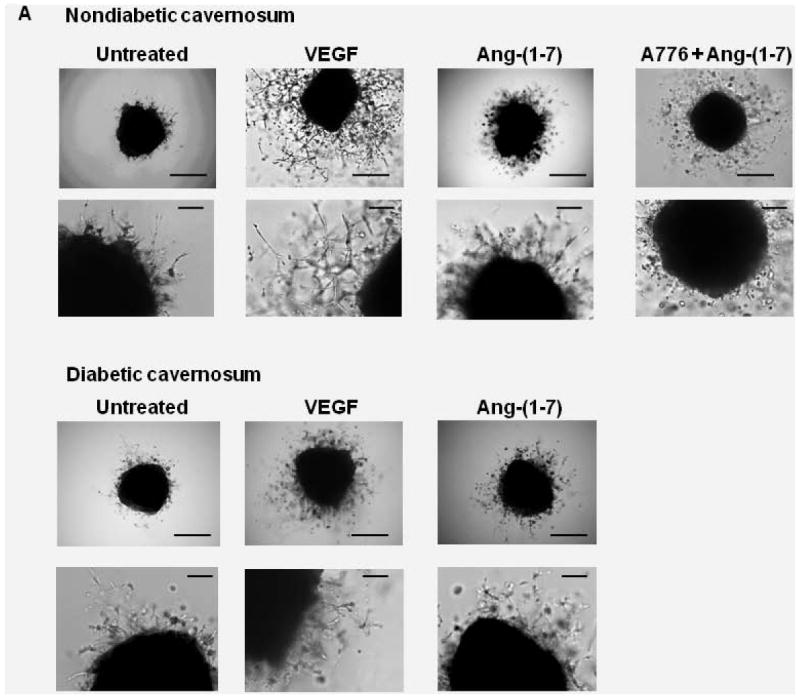

In vitro angiogenic response in matrigel was characterized by migration of sinusoidal endothelial cells into the 3D matrix, followed by sprouting and formation of tubular structures. In the untreated cavernosal strips cultured in the basal medium, sprouting of sinusoidal endothelial cells was observed by day-3. Formation of endothelial tubes was observed by day 5. Tubular structures tended to degenerate from day 7 onwards. Treatment with VEGF (100 nM) induced sprouting and tube formation by migrated endothelial cells by day-4 that continued to grow into an extensive network. Ang-(1-7) (100 nM) induced endothelial sprouting and tube formation by day 4 that continued to grow, however, the density of tubular network was not as extensive as observed with VEGF. For comparison of quantitative responses, the tubular length was measured at day 7 (Figure 1A). Ang-(1-7) stimulated tube formation (P<0.0001 vs untreated, n=5) that was partially inhibited by A779 (10 μM), a Mas1 receptor antagonist (P<0.05, n=4).

Figure 1. Ang-(1-7)-induced vascular endothelial tube formation in cavernosal tissue derived from nondiabetic or diabetic mice.

A. Representative bright field images of cavernosal strips showing angiogenic response in matrigel. Cavernosal strips obtained from either nondiabetic or diabetic mice were treated with either basal medium/EBM2, 100 nM VEGF, 100 nM Ang-(1-7), or 100 nM Ang-(1-7) in the presence of 10 μM A779. Images in upper and lower panels were obtained at 4x or 20x objective. Scale bar equals 200 (upper panel) or 50 microns (lower panel). B. Effects of different treatments on the tubular formation observed in cavernosal tissues derived from nondiabetic and diabetic mice. Ang-(1-7) increased tubular formation in cavernosal tissue (P<0.0001 compared to the untreated, n=5), which was partially inhibited by A779 (P<0.007, n=4). Ang-(1-7) stimulated endothelial tube formation in cavernosal tissue derived from diabetic mice (P<0.01 compared untreated, n=5), which was lower than that observed in the nondiabetic cavernosum (P<0.005). VEGF induced robust angiogenic response in the nondiabetic cavernosum which was reduced in diabetes (P<0.03, n=5).

In diabetic cavernosal tissue, Ang-(1-7) (100 nM) stimulated endothelial tube formation (P<0.01 compared to untreated, n=5, Figure 1B), however this response was lower than that observed in nondiabetic (P<0.005, Figure 1B). Furthermore, response to VEGF (100 nM) was also reduced in diabetic cavernosum (P<0.03 vs nondiabetic, n=5, Figure 1B).

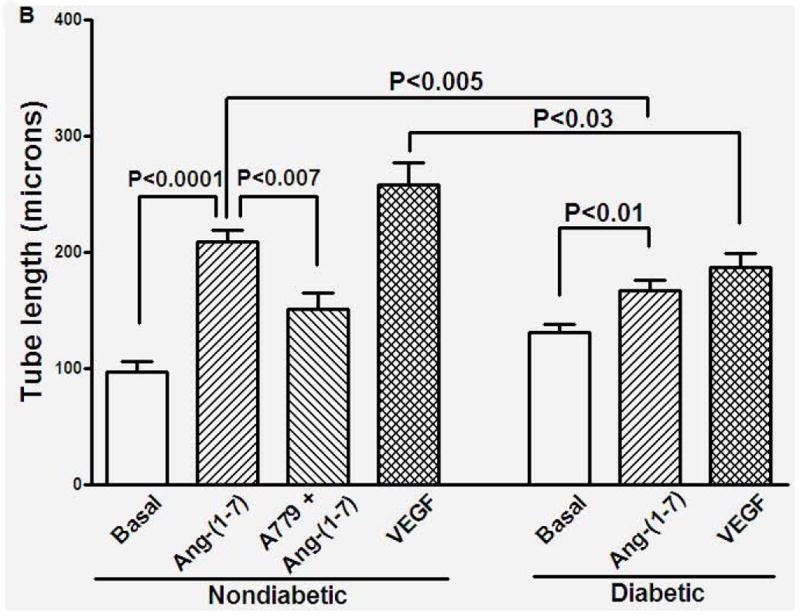

Then, we tested if chronic administration of Ang-(1-7) would reverse the impaired angiogenic function of diabetic cavernosum. Diabetic mice were treated with saline or Ang-(1-7) for four weeks and the cavernosa were evaluated for VEGF-induced angiogenesis. The endothelial tube formation induced by VEGF was lower in diabetic cavernosa (P<0.05 vs nondiabetic) and Ang-(1-7) treatment robustly enhanced this response (P<0.03 vs untreated diabetic, n=5, Figure 2).

Figure 2. VEGF-induced endothelial tube formation is impaired in cavernosal tissue derived from diabetic mice and this dysfunction was reversed by in vivo Ang-(1-7) treatment.

A. Representative bright field images of cavernosal strips showing angiogenic response in matrigel. Tissue strips were obtained from either nondiabetic, diabetic or Ang-(1-7)-treated diabetic mice, treated with 100 nM VEGF. Images were obtained at 4x objective. Scale bar equals 200 microns. B. VEGF induced a robust angiogenic response in cavernosal tissue derived from nondiabetic mice, which was reduced in diabetic cavernosum (P<0.05, n=5). Cavernosal tissue derived from diabetic mice treated with Ang-(1-7) for four weeks, showed robust angiogenic response to VEGF (P<0.05 compared to untreated diabetic).

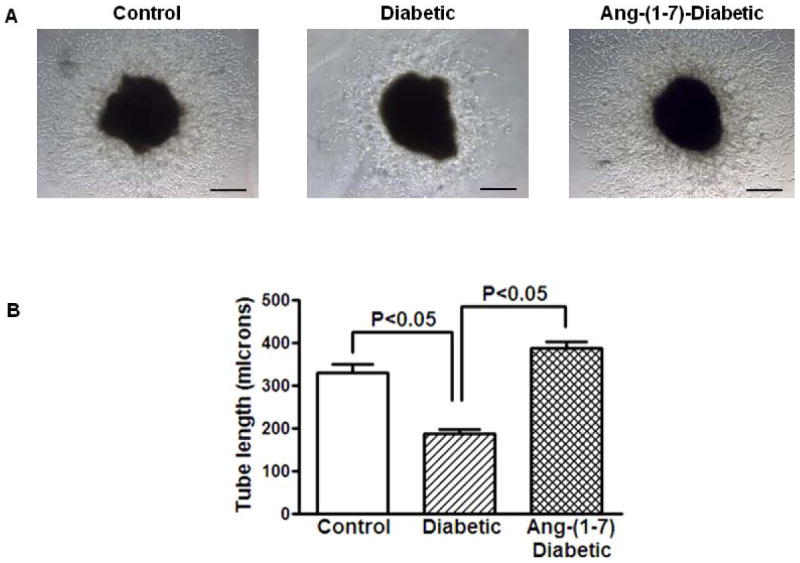

Ang-(1-7) increases the circulating BMPCs in long-term diabetes

Diabetes decreases mobilization of BMPCs into the peripheral circulation, which in turn cause/accelerate angiogenic dysfunction of cavernosa [25,30]. Therefore we tested if BMPCs contribute to the angiogenic functions of Ang-(1-7) in diabetes. The circulating BMPCs, Lin- or LS cells, were enumerated in different treatment groups. Long-term diabetes decreased the circulating BM-Lin- and LS cells, (P<0.05, vs control, n=7) (Figure 3A). Ang-(1-7) treatment normalized the circulating number of Lin- and LS cells (P<0.02 and P<0.05, respectively, Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Reversal of diabetic dysfunction in bone marrow stem/progenitor cells (BMPCs) by Ang-(1-7) treatment.

A. Diabetes was associated with reduced number of circulating BMPCs, Lin- or LS cells (P<0.05, n=6). Ang-(1-7) treatment increased the number of circulating Lin- or LS cells (P<0.02 and P<0.05, respectively, n=6). Ang-(1-7) has no significant effect on circulating BMPCs in nondiabetic mice. B. Ex vivo proliferation of resident BMPCs, as measured by BrdU incorporation is reduced in diabetes (P<0.003), which was reversed by Ang-(1-7) treatment (P<0.002).

Proliferation of primitive BMPCs is a highly regulatory process and is essential for physiological and induced mobilization of BMPCs [23]. Therefore, we tested if Ang-(1-7) affected proliferation of BMPCs in diabetes. Proliferation was evaluated ex vivo by determining BrdU incorporation. This response was highly impaired in cells isolated from diabetic mice (P<0.003 vs nondiabetic) and this impairment was reversed by administration of Ang-(1-7) (P<0.002 vs untreated diabetic, n=7, Figure 3B).

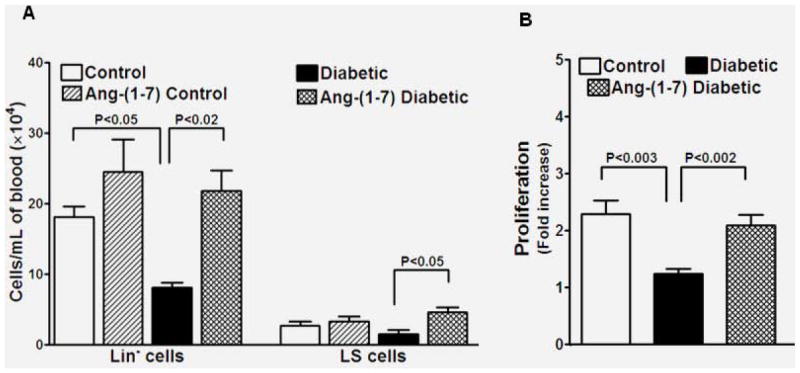

Ang-(1-7) increases paracrine pro-angiogenic function of diabetic BMPCs

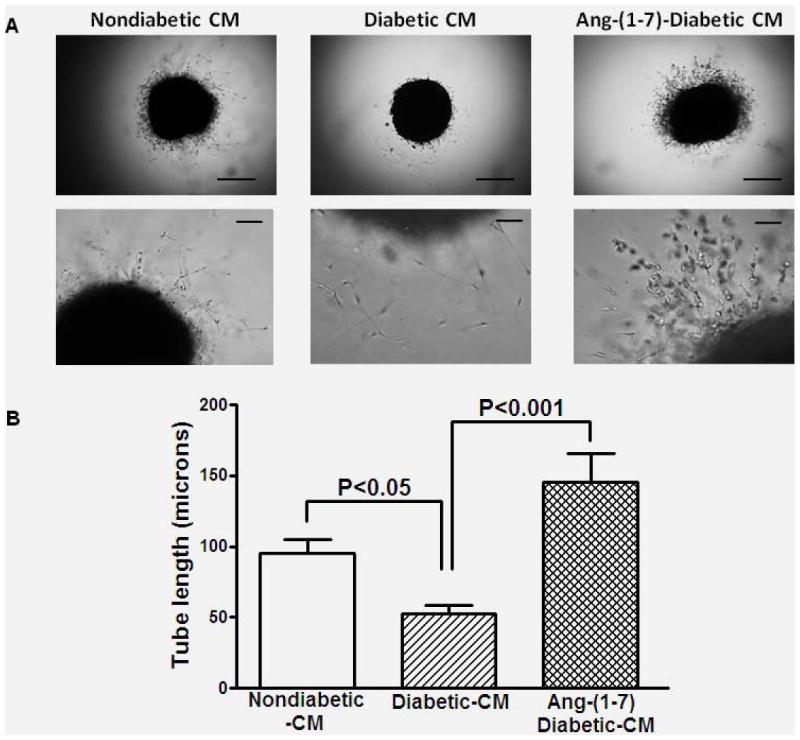

BMPCs stimulate the angiogenic functions intrinsic for the resident vasculature largely via paracrine effects [24]. We tested if Ang-(1-7)-mediated improvement in the cavernosal angiogenic response involves the paracrine functions of BMPCs. Conditioned media (CM) were obtained from control, diabetic or Ang-(1-7)-treated diabetic BMSPCs and were evaluated for the proangiogenic effects in nondiabetic cavernosum. Control-CM stimulated angiogenic response, which was either impaired or not observed when treated with diabetic-CM (P<0.05, n=4, Figure 4). CM derived from Ang-(1-7)-treated diabetic mice stimulated robust angiogenic response (P<0.001 vs diabetic-CM, n=4, Figure 4).

Figure 4. Reversal of paracrine angiogenic dysfunction in diabetic BMPCs by Ang-(1-7).

A. Conditioned media (CM) or cell-free supernatants derived from nondiabetic, diabetic or Ang-(1-7)-treated diabetic BMPCs were evaluated for their angiogenic functions in cavernosal strips derived from nondiabetic mice. A. Representative bright field images of cavernosal strips treated with CM derived from different BMPCs showing angiogenic response in matrigel. Images in upper and lower panels were obtained at 4x or 20x objective. Scale bar equals 200 (upper panel) or 50 microns (lower panel). B. Endothelial tube formation induced by Diabetic-CM was significantly lower than that induced by nondiabetic-CM (P<0.05). Ang-(1-7)-diabetic-CM induced robust increase in the endothelial tube formation (P<0.001 compared to diabetic-CM).

Ang-(1-7) induces pro-angiogenic switch in BMPCs and in cavernosum in diabetes

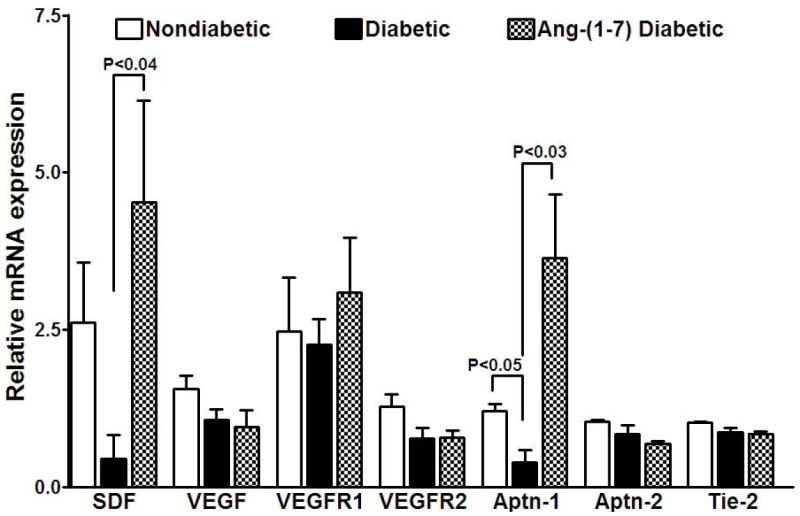

Then, we evaluated the expression of proangiogenic factors in BMPCs and in cavernosal tissue to delineate the soluble factors produced by BMPCs and their effects on cavernosum. The gene expression of selected factors, SDF, VEGF, Aptn-1 and Aptn-2, and their receptors VEGFR1, VEGFR2 and Tie-2, was quantified in BMPCs and cavernosal tissues from different treatment groups.

In BMPCs (Figure 5), expression of VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, Aptn-2 and Tie-2 were not altered by diabetes, whereas significant decrease was observed in the expression of SDF and Aptn-1 (P<0.05) compared to nondiabetic. Ang-(1-7) reversed this decrease (SDF, P<0.04, and Aptn-1, P<0.03, vs diabetic, n=5).

Figure 5. Reversal of diabetes-induced changes in the expression of selected angiogenic factors in BMPCs by Ang-(1-7).

Diabetes resulted in down-regulation of angiogenic factors, stromal-derived factor-1α (SDF) (P<0.05, n=5) and angiopoietin-1 (Aptn-1) (P<0.05) in BMPCs compared to nondiabetic. Ang-(1-7) treatment reversed the diabetes-induced changes in the expression of SDF (P<0.04) and Aptn-1 (P<0.03). Expression of VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, Aptn-2 or Tie2 was no affected in diabetes or by Ang-(1-7) treatment.

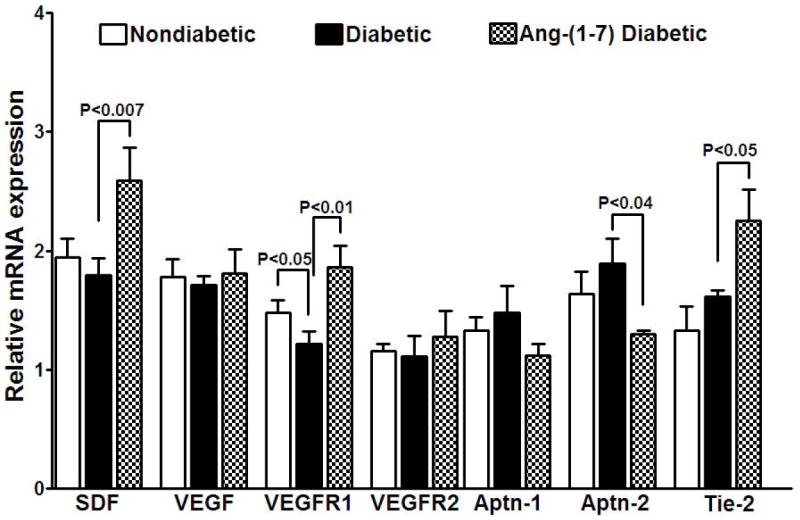

In cavernosum (Figure 6), while the expression of SDF, VEGF and Aptn-1 were unchanged in diabetes, the VEGFR1 expression was down-regulated (P<0.05 vs control, n=5). Interestingly, Ang-(1-7) differentially altered the expression of angiogenic factors and their receptors: Aptn-2 was down-regulated (P<0.04), and Tie-2 (P<0.05), SDF (P<0.007), and VEGFR1 (P<0.01) were up-regulated, and Aptn-1, VEGF and VEGFR2 were unaltered (n=5, vs untreated diabetic).

Figure 6. Ang-(1-7) up-regulates the expression of selected angiogenic factors in diabetic cavernosum.

Diabetes resulted in the down-regulation of VEGFR1 (P<0.05 vs nondiabetic) in cavernosum that was reversed by Ang-(1-7) treatment (P<0.01 vs diabetic) while other factors were unaltered. Ang-(1-7) treatment up-regulated SDF (P<0.007), and Tie-2 (P<0.05), and down-regulated the expression of Aptn-2 (P<0.04), compared to the untreated diabetic cavernosum.

Discussion

This study reports several novel findings: 1. Ang-(1-7) is pro-angiogenic in the mouse corpus cavernosum, 2) cavernosal angiogenic function is impaired in long-term diabetes, which can be reversed by Ang-(1-7), 3) diabetes is associated with decreased number and impaired paracrine angiogenic function of circulating BMPCs, both of which were reversed by Ang-(1-7), and 5) Ang-(1-7) induced pro-angiogenic switch in the expression profile in both cavernosum and BMPCs.

The current study provides direct evidence for the pro-angiogenic function of Ang-(1-7) in mouse corpus cavernosum. Earlier studies have shown that Ang-(1-7) is either pro-angiogenic or antiangiogenic in different assay systems. In culture-derived endothelial progenitor cells, ACE2-expression enhanced angiogenic function in matrigel assay that was dependent on Ang-(1-7)/Mas pathway [31]. Similar findings were observed in rat microvascular endothelial cells [32]. These findings are further supported by in vivo studies in rat hindlimb ischemia model that showed enhanced neovascularization of ischemic limb by Ang-(1-7) [32]. In contrast, inhibitory effect of Ang-(1-7) was observed in mouse sponge model of angiogenesis [33], and in lung and breast tumor xenografts [34]. These reported differences could be due to the underlying mechanisms that mediate cancer angiogenesis, which are complex and believed to be distinct from physiological/therapeutic angiogenesis [35].

Diabetes is known to impair endothelial functions, both dilatory and angiogenic, thus leading to vascular disease [36]. While the vasodilatory dysfunction was well documented in cavernosum in experimental studies, no studies were focused at angiogenic function. The current study reports that long-term diabetes is associated with angiogenic dysfunction in corpus cavernosum that was characterized by reduced response to VEGF, and that Ang-(1-7) reversed this impairment in vitro and ex vivo. Recent study by Yin et al [37] demonstrated diabetic dysfunction in vitro in cavernosal angiogensis in a similar assay system. Increased oxidative stress due to NADPH oxidase overactivity resulting in reduced nitric oxide (NO) availability is considered to be a major underlying mechanism of Ang-(1-7) protective effects [38]. Furthermore, Ang-(1-7) has been shown to enhance NO bioavailability, in part, by reducing NADPH activity and by activating/upregulating eNOS [39].

Current study provides evidence for the role of BMPCs in the proangiogenic effects of Ang-(1-7) in diabetes. Diabetes is known to be associated with decreased function and number of circulating BMPCs that play an important role in re-endothelialization and maintaining vascular health largely by paracrine mechanisms [24,25]. Role of BMPCs in cavernosal endothelial function is poorly studied. While stem/progenitor cells of diverse sources were shown to either reverse or improve erectile dysfunction in experimental diabetes [40], no studies have focused at targeting enhancing the mobilization of BMPCs that was impaired in diabetes. This study shows that Ang-(1-7) reverses the diabetes-induced decrease in mobilization of BMPCs. Furthermore, Ang-(1-7) reversed the paracrine proangiogenic dysfunction. These beneficial effects were associated with increased proliferation of resident BMPCs, an important event that precedes mobilization into the circulation [23], which was also impaired in diabetes. Earlier studies have implicated BMPC mobilization in the protective functions of Ang-(1-7) in experimental models of myocardial [41] or retinal ischemia [15].

Re-endothelialization of vasculature by BMPCs has been shown to involve both trans-differentiation into endothelial cells and paracrine mechanisms. The latter mechanism is strongly supported by several studies and the vascular engraftment by BMPCs is evidently not more than 10% even at the stage of maximum restoration of blood flow following ischemic injury [19]. Recent studies indicate that paracrine angiogenic effects of human or murine BMPCs are impaired in diabetes [42]. Therefore, current study tested the hypothesis that the reversal of paracrine dysfunction in BMPCs is an underlying mechanism of beneficial effects of Ang-(1-7) in BMPCs. Current study involving cell-free supernatants support this hypothesis and that at least in part contributes to the reversal of diabetic angiogenic dysfunction in cavernosum.

The soluble factors released by circulating BMPCs have autocrine and paracrine functions i.e. they modulate the function of the cells themselves as well as modulate the target tissue/cell functions such as vascular endothelium [43]. In the current study, gene expression assays of selected pro-angiogenic factors in BMPCs and corpus cavernosum revealed the involvement of factors that are produced by BMPCs in modulation of angiogenic function in cavernosum. Murine BMPCs express SDF, VEGF and Aptn-1 and their receptors, CXCR4, VEGFR1, VEGFR2 and Tie-2, and the expression was differentially affected in diabetes and by treatment with Ang-(1-7). Specifically, diabetes down-regulated SDF and Aptn-1 expression in diabetic BMPCs, and VEGFR1 expression in cavernosum. Ang-(1-7) treatment reversed these diabetes-induced molecular changes and further up-regulated SDF and Tie-2, and down-regulated Aptn-2 in the cavernosal tissue. SDF supports the proliferation and migratory functions of BMPCs and vascular endothelial cells via its actions on CXCR4 receptor [44,45]. On the other hand, BMPCs are selectively recruited by tissue-derived SDF thus concentrating the paracrine effects of BMPCs in the areas, where endothelium is dysfunctional. Our study shows that SDF expression in diabetic BMPCs is impaired and that Ang-(1-7) reversed the impairment and furthermore, enhanced SDF expression in cavernosum, the target tissue.

VEGF is a well-studied growth factor for its physiological and pathological angiogenic effects in different clinical settings. In the context of diabetes, pathological or therapeutic outcomes vary with the organ and the availability of several other factors such as NO that modulate angiogenesis [46-48]. In the current study, expression of VEGF in BMPCs or corpus cavernosum was not altered in diabetes. Interestingly, VEGFR1 expression was down-regulated in diabetic corpus cavernosum that was reversed by Ang-(1-7) thus restoring the angiogenic response in cavernosal vasculature when exposed to VEGF. Aptn-1 mediates migration, adhesion and survival of endothelial cells by acting on Tie-2 receptors, and Aptn-2 opposes the actions of Aptn-1 and promotes vascular regression [49]. Along similar lines, Aptn-1 and Aptn-2 have opposing effects in BMPCs. BMPC-derived Aptn-1 enhances the proliferation of BMPCs via autocrine mechanism and promotes angiogenesis in the target tissue via paracrine effects by stimulating migration of endothelial cells and by inducing the formation of vascular network [50]. Our findings demonstrate that the expression of Aptn-1 is down-regulated in diabetic BMPCs, which was reversed by Ang-(1-7). In addition, the anti-angiogenic factor, Aptn-2, was down-regulated by Ang-(1-7) in the diabetic corpus cavernosum thus enhancing the paracrine proangiogenic functions of BMPCs via Aptn-1.

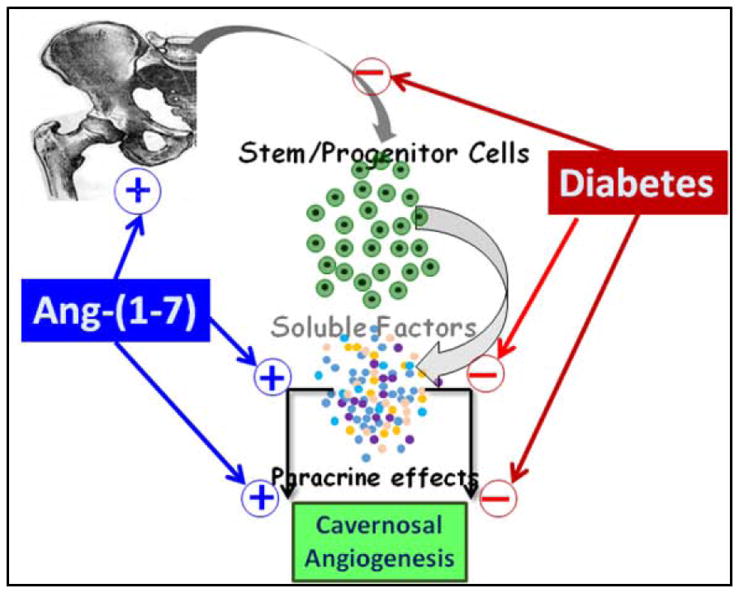

In conclusion, long-term diabetes is associated with angiogenic dysfunction in corpus cavernosum, decreased number and paracrine function of circulating BMPCs. The paracrine dysfunction is at least in part, due to the down-regulation of SDF and Aptn-1 in BMPCs, and due to down regulation of VEGFR1 in cavernosum. Ang-(1-7) reversed diabetes-induced molecular changes, and further stimulated the expression of proangiogenic Tie-2 and SDF, and decreased the expression of anti-angiogenic Aptn-2 in cavernosum. The summary of findings is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Possible mechanism of the reversal of diabetic dysfunction in cavernosal angiogenesis by Ang-(1-7) in diabetes.

Bone marrow stem/progenitor cells (BMPCs) are mobilized into circulation in physiological conditions and maintain endothelial health by producing paracrine factors such as stromal-derived factor-1α (SDF), VEGF and angiopoietin-1. In long-term diabetes, mobilization of BMPCs is decreased and their paracrine protective functions are impaired. The latter could be, at least in part, due to decreased expression of SDF and Aptn-1 in BMPCs, and VEGFR1 in cavernosam. Therefore, angiogenic function of cavernosal microvasculature is diminished. Treatment with Ang-(1-7) enhanced the mobilization of BMPCs and their paracrine angiogenic function. This vasoprotective effect is in part, due to the reversal of diabetic changes in the expression of paracrine factors, and in the cavernosal microvasculature - increased expression of SDF and Tie-2, and decreased expression of Aptn-2, an antiangiogenic factor (molecular changes are not included in the schematic for clarity).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Anil Wagh for technical contribution.

This work and the use of Core Biology Facility at North Dakota State University were made possible by NIH Grant Number P30 GM103332-01 from the National Center for Research Resources. This work was partly supported by the New Investigator Award from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP).

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, Moss SE, Cruickshanks KJ. Prevalence of self-reported erectile dysfunction in people with long-term IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:135–141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedele D, Bortolotti A, Coscelli C, Santeusanio F, Chatenoud L, et al. Erectile dysfunction in type 1 and type 2 diabetics in Italy. On behalf of Gruppo Italiano Studio Deficit Erettile nei Diabetici. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:524–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saenz de Tejada I, Goldstein I, Azadzoi K, Krane RJ, Cohen RA. Impaired neurogenic and endothelium-mediated relaxation of penile smooth muscle from diabetic men with impotence. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1025–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904203201601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bivalacqua TJ, Usta MF, Champion HC, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ. Endothelial dysfunction in erectile dysfunction: role of the endothelium in erectile physiology and disease. J Androl. 2003;24:S17–37. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner AJ, Tipnis SR, Guy JL, Rice G, Hooper NM. ACEH/ACE2 is a novel mammalian metallocarboxypeptidase and a homologue of angiotensin-converting enzyme insensitive to ACE inhibitors. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:346–353. doi: 10.1139/y02-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katovich MJ, Grobe JL, Raizada MK. Angiotensin-(1-7) as an antihypertensive, antifibrotic target. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2008;10:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Simoes ESAC. Recent advances in the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin(1-7)-Mas axis. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:519–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira AJ, Murca TM, Fraga-Silva RA, Castro CH, Raizada MK, et al. New cardiovascular and pulmonary therapeutic strategies based on the Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1-7)/mas receptor axis. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/147825. 147825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Costa Goncalves AC, Leite R, Fraga-Silva RA, Pinheiro SV, Reis AB, et al. Evidence that the vasodilator angiotensin-(1-7)-Mas axis plays an important role in erectile function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2588–2596. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00173.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Costa Goncalves AC, Fraga-Silva RA, Leite R, Santos RA. AVE 0991, a non-peptide Mas-receptor agonist, facilitates penile erection. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:850–855. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.068551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraga-Silva RA, Costa-Fraga FP, Savergnini SQ, De Sousa FB, Montecucco F, et al. An oral formulation of angiotensin-(1-7) reverses corpus cavernosum damages induced by hypercholesterolemia. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2430–2442. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraga-Silva RA, Montecucco F, Mach F, Santos RA, Stergiopulos N. Pathophysiological role of the renin-angiotensin system on erectile dysfunction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:978–985. doi: 10.1111/eci.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilarkaje N, Yousif MH, El-Hashim AZ, Makki B, Akhtar S, et al. Role of angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1-7) in diabetes-induced oxidative DNA damage in the corpus cavernosum. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park KE, Pepine CJ. Bone marrow-derived cells and hypertension. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:1139–1148. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulati R, Simari RD. Defining the potential for cell therapy for vascular disease using animal models. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:130–137. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekiguchi H, Ii M, Losordo DW. The relative potency and safety of endothelial progenitor cells and unselected mononuclear cells for recovery from myocardial infarction and ischemia. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:235–242. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An G, Ji C, Wei Z, Chen H, Zhang J. The therapeutic role of VEGF-expressing muscle-derived stem cells in acute penile cavernosal injury. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1988–2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu X, Villalta J, Ferretti L, Fandel TM, Albersen M, et al. Effects of intravenous injection of adipose-derived stem cells in a rat model of radiation therapy-induced erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1834–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon SM, Lee YK, Yokoyama A, Jung SY, Masuda H, et al. Differential activity of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell subpopulations for EPC development and ischemic neovascularization. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tongers J, Losordo DW, Landmesser U. Stem and progenitor cell-based therapy in ischaemic heart disease: promise, uncertainties, and challenges. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1197–1206. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojakowski W, Landmesser U, Bachowski R, Jadczyk T, Tendera M. Mobilization of stem and progenitor cells in cardiovascular diseases. Leukemia. 2012;26:23–33. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez P, Carrillo E, Velez C, Hita-Contreras F, Martinez-Amat A, et al. Regulatory systems in bone marrow for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells mobilization and homing. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/312656. 312656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabbany SY, Heissig B, Hattori K, Rafii S. Molecular pathways regulating mobilization of marrow-derived stem cells for tissue revascularization. Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:109–117. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarajapu YP, Grant MB. The promise of cell-based therapies for diabetic complications: challenges and solutions. Circ Res. 2010;106:854–869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albiero M, Fadini GP. Strategies for enhancing progenitor cell mobilization and function in diabetes. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10:310–321. doi: 10.2174/157016112799959387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fadini GP, Albiero M, Vigili de Kreutzenberg S, Boscaro E, Cappellari R, et al. Diabetes impairs stem cell and proangiogenic cell mobilization in humans. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:943–949. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarajapu YP, Caballero S, Verma A, Nakagawa T, Lo MC, et al. Blockade of NADPH oxidase restores vasoreparative function in diabetic CD34+ cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5093–5104. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-70911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caballero S, Sengupta N, Afzal A, Chang KH, Li Calzi S, et al. Ischemic vascular damage can be repaired by healthy, but not diabetic, endothelial progenitor cells. Diabetes. 2007;56:960–967. doi: 10.2337/db06-1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarajapu YP, Bhatwadekar AD, Caballero S, Hazra S, Shenoy V, et al. Activation of the ACE2/angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas receptor axis enhances the reparative function of dysfunctional diabetic endothelial progenitors. Diabetes. 2013;62:1258–1269. doi: 10.2337/db12-0808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albiero M, Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Restoring stem cell mobilization to promote vascular repair in diabetes. Vascul Pharmacol. 2013;58:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Xiao X, Chen S, Zhang C, Yi D, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 priming enhances the function of endothelial progenitor cells and their therapeutic efficacy. Hypertension. 2013;61:681–689. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann BR, Stodola TJ, Wangner JR, Greene AS. Ang-(1-7) Induced MAS1 Receptor-Mediated Angiogenesis in the Rat Microvasculature. FASEB J. 2013;27:1165–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machado RD, Santos RA, Andrade SP. Mechanisms of angiotensin-(1-7)-induced inhibition of angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R994–R1000. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.4.R994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soto-Pantoja DR, Menon J, Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits tumor angiogenesis in human lung cancer xenografts with a reduction in vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1676–1683. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kucera T, Lammert E. Ancestral vascular tube formation and its adoption by tumors. Biol Chem. 2009;390:985–994. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N, Androulakis E, Siasos G, Latsios G, et al. Diabetes mellitus-associated vascular impairment: novel circulating biomarkers and therapeutic approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin GN, Ryu JK, Kwon MH, Shin SH, Jin HR, et al. Matrigel-based sprouting endothelial cell culture system from mouse corpus cavernosum is potentially useful for the study of endothelial and erectile dysfunction related to high-glucose exposure. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1760–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabelo LA, Alenina N, Bader M. ACE2-angiotensin-(1-7)-Mas axis and oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:154–160. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin CS, Xin ZC, Wang Z, Deng C, Huang YC, et al. Stem cell therapy for erectile dysfunction: a critical review. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:343–351. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Qian C, Roks AJ, Westermann D, Schumacher SM, et al. Circulating rather than cardiac angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates cardioprotection after myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:286–293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.905968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Awad O, Jiao C, Ma N, Dunnwald M, Schatteman GC. Obese diabetic mouse environment differentially affects primitive and monocytic endothelial cell progenitors. Stem Cells. 2005;23:575–583. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burchfield JS, Dimmeler S. Role of paracrine factors in stem and progenitor cell mediated cardiac repair and tissue fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2008;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Falco E, Porcelli D, Torella AR, Straino S, Iachininoto MG, et al. SDF-1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia-induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104:3472–3482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liekens S, Schols D, Hatse S. CXCL12-CXCR4 axis in angiogenesis, metastasis and stem cell mobilization. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3903–3920. doi: 10.2174/138161210794455003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isner JM. Therapeutic angiogenesis: a new frontier for vascular therapy. Vasc Med. 1996;1:79–87. doi: 10.1177/1358863X9600100114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aiello LP, Wong JS. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic vascular complications. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S113–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryu JK, Shin HY, Song SU, Oh SM, Piao S, et al. Downregulation of angiogenic factors and their downstream target molecules affects the deterioration of erectile function in a rat model of hypercholesterolemia. Urology. 2006;67:1329–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagiani E, Christofori G. Angiopoietins in angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukuhara S, Sako K, Minami T, Noda K, Kim HZ, et al. Differential function of Tie2 at cell-cell contacts and cellsubstratum contacts regulated by angiopoietin-1. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:513–526. doi: 10.1038/ncb1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.