Abstract

Food volume could influence both the portions that people take and the amount that they eat, but these effects have had little investigation. The influence of food volume was tested by systematically reducing the flake size of a breakfast cereal so that the cereal was more compact and the same weight filled a smaller volume. In a crossover design, 41 adults ate cereal for breakfast once a week for four weeks during 2011-2012. The cereal was either standard wheat flakes or the same cereal crushed to reduce the volume to 80%, 60%, or 40% of the standard. A constant weight of cereal was provided in an opaque container and participants poured the amount they wanted into a bowl, added fat-free milk and non-calorie sweetener as desired, and consumed as much as they wanted. Results from a mixed linear model showed that as flake size was reduced, subjects poured a smaller volume of cereal, but still took a greater amount by weight and energy content (both P<0.0001). Despite these differences, subjects estimated that they had taken a similar number of calories of all versions of the cereal. They ate most of the cereal they took, so as flake size was reduced, breakfast energy intake increased from 286±18 to 358±19 kcal, an increase of 34±7% (P<0.0001). These findings demonstrate that variations in food volume associated with the size of a food’s individual pieces affect the portion served, which in turn affects energy intake.

Keywords: food volume, portion size, energy intake, breakfast cereal, adults

INTRODUCTION

National dietary guidelines define recommended amounts of most food groups in terms of volume.1 For some voluminous foods, such as raw leafy greens2 and puffed cereals3, the recommended amount is larger than for more compact versions of these foods. For other foods, however, recommended amounts have not been adjusted for variations in physical properties that affect volume such as aeration, cooking, and the size and shape of individual pieces. Thus, the food weight and energy required to fill a given volume can vary. Such variations in the energy content of recommended amounts could be a challenge to the maintenance of energy balance. The present study tests the hypothesis that a physical property of food affecting its volume, specifically the size of the individual pieces, will influence the amount served, which will in turn affect energy intake.

Food volume is of particular interest because of the cues it provides about portion size. Although many studies have demonstrated that portion size affects energy intake4-9, in most of these studies the amount of available food varied simultaneously in weight and volume. Food volume can be dissociated from food weight by varying the degree of aeration, and studies have shown that incorporating air into extruded snacks10 or milkshakes11 to increase the volume led to a reduction in energy intake. Food volume can also be influenced by variations in the size and shape of individual food pieces, since the same weight of food in large or irregular pieces packs less closely together. In the present study, the size of food pieces was systematically varied in order to determine for the first time whether the resulting differences in volume, independent of weight, affect the amount of food taken and consumed. Breakfast cereal was chosen as the test food since it has a wide variety of forms with pieces in many sizes and shapes, which could make it difficult to select an appropriate portion.

METHODS

Study Design

This study used a crossover design, in which subjects were presented all of the experimental meals in a specified sequence over time, thus serving as their own controls. Once a week for four weeks, participants ate cereal for breakfast in the laboratory. Across meals, the cereal was either standard wheat flakes or the same cereal crushed to reduce the flake size and volume to 80%, 60%, or 40% of the standard. The order of presenting the four experimental meals was counterbalanced across subjects using Latin squares, so that in each study week the four versions of cereal were served with similar frequency.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the local community and university campus using newspapers, leaflets, and electronic newsletters. Potential subjects came to the laboratory and had their height and weight measured and completed demographic and screening questionnaires. Women and men were eligible for the study if they were 19-45 years old, had a body mass index of 18.5-35.0 kg/m2, regularly ate breakfast, ate cereal occasionally, and were willing to eat wheat flakes with fat-free milk and without sugar. Individuals were not eligible if they were dieting, athletes in training, pregnant or breastfeeding, smokers, or using medications that affect appetite or food intake. The Institutional Review Board of The Pennsylvania State University approved the protocol. Subjects were told that the study purpose was to investigate the effects of a breakfast meal; they provided written informed consent and were financially compensated for their participation. The study was conducted between July 2011 and April 2012.

Forty-five participants were enrolled, but four did not complete the study; two withdrew for personal reasons and two failed to attend scheduled meals. The final sample consisted of 41 subjects (24 women; 17 men) with a mean (±SEM) age of 27.2±1.2 years and body mass index of 24.2±0.6 kg/m2. Seven participants (17%) were overweight and 6 (15%) were obese. Mean scores on the Eating Inventory12 were 9.2±0.7 for dietary restraint (potential range 0-21), 4.3±0.4 for disinhibition (potential range 0-16), and 3.6±0.4 for tendency toward hunger (potential range 0-14).

Test Foods and Meal Procedures

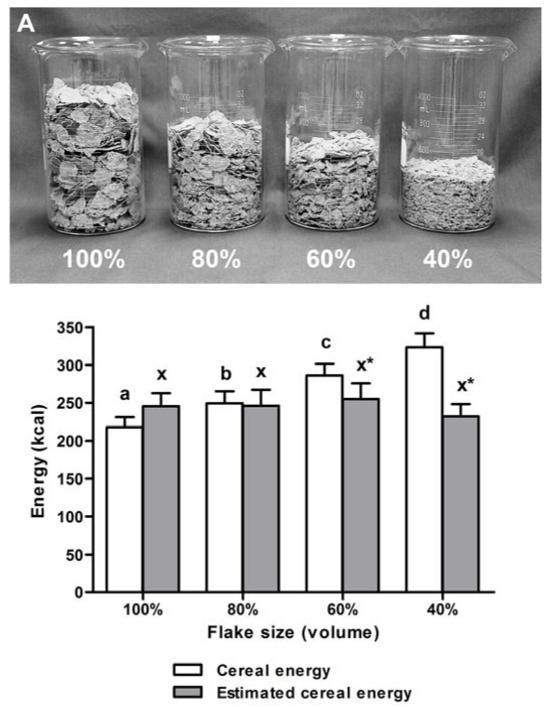

In order to maintain consistent taste and nutrient composition, the same type of cereal was served at all meals (Wheaties; General Mills, Inc., Minneapolis, MN; energy density 3.5 kcal/g). For the cereal with standard (100%) flake size, the commercially available product was used; measurements showed that 140 g of this cereal filled a 1000-ml beaker. For the remaining meals, the cereal was crushed following a uniform procedure: 140 g of standard cereal was spread within a sealed plastic bag and crushed with a rolling pin a specified number of times. The crushed cereal was measured in a 1000-ml beaker to ensure that the volume was reduced to 80%, 60%, or 40% (Figure 1A). At each meal, the weight of cereal provided was 280 g and the volume differed according to the flake size (2000, 1600, 1200, or 800 ml).

Figure 1.

(A) These beakers illustrate the reduction in the flake size and volume of breakfast cereal served in a crossover study of 41 adults. The same weight of the commercially available cereal (100%) was crushed using a uniform procedure to reduce the volume to 80%, 60%, and 40%. In the study, participants poured the cereal from opaque containers and could not see the cereal until it was in the bowl. (B) This graph shows the energy content of the cereal that subjects poured compared with their estimates of the number of calories in the cereal they poured (mean ± standard error of the mean). For cereal energy, means with different letters are significantly different (P< 0.04); for estimated cereal energy, there were no significant differences between means. Thus, as cereal flake size and volume decreased, subjects took more calories, but their estimates of the calories taken did not change. Estimates marked with an asterisk are significantly different from the actual energy content of the cereal with the same flake size (P< 0.04).

Subjects were instructed not to eat any food after 10 pm the night before and during the morning before each breakfast, and to drink nothing but water during this time. Upon arrival for breakfast, subjects were seated in individual cubicles and were not allowed reading material or other distractions. Participants rated their hunger and fullness using 100-mm visual analog scales13, which were anchored on the left with “Not at all hungry” and on the right with “Extremely hungry”, with similar anchors for fullness. Subjects were then brought the cereal in a 3.8-liter opaque container typically used for dispensing cereal. The opening at the top of the container did not allow the contents to be easily viewed, but was large enough for the cereal to flow freely. Participants were instructed to pour the amount of cereal they would like for their breakfast into a 900-ml bowl and were informed that they could not request additional cereal; the cereal container was then removed. Next, participants were brought a non-opaque container of 475 g of fat-free milk and instructed to add milk to the cereal as desired; the milk container was then removed. Subjects estimated the number of calories of cereal they had poured in the bowl and rated cereal characteristics (pleasantness of appearance, taste, and texture) using visual analog scales after taking one bite of the cereal. Non-calorie sweetener was provided with the meal and a pre-selected non-calorie hot beverage was served, to which creamer and non-calorie sweetener could be added as desired. Participants were instructed to consume as much of the meal as they wanted and to take as much time as they wanted.

Outcome Assessments

Containers of cereal and milk were weighed before and after serving to determine the weight that subjects had poured. The volume of poured cereal was calculated from the weight using the ratio for each cereal flake size (2000, 1600, 1200, or 800 ml per 280 g cereal). Although subjects ate most of the cereal they poured, any uneaten cereal was strained of milk so that the weights of the remaining cereal and milk could be determined separately. Energy intakes of each breakfast item were calculated from the difference between pre- and post-meal weights and using data from a standard nutrient database.14

Data Analysis

Outcomes were analyzed using a mixed linear model with repeated measures. The fixed effects in the model were cereal volume (100%, 80%, 60%, or 40%), study week, and subject sex; subjects were treated as a random effect. The Tukey-Kramer method was used to adjust significance levels for multiple pairwise comparisons. Study outcomes were the volume and weight of cereal poured and consumed; cereal and meal energy intakes; and subject ratings of hunger, fullness, and cereal taste, texture, and appearance. Accuracy of calorie estimation was defined as the difference between the number of calories in the cereal poured at each meal and the subject’s estimate of this number. Analysis of covariance was used to determine whether the relationship between cereal volume and intake was affected by subject characteristics of age, sex, body mass index, dietary restraint, disinhibition, tendency toward hunger, and calorie estimation accuracy. Results are reported as mean ±SEM and were considered significant at P<0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.3, 2011, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As cereal flake size was reduced, participants decreased the volume of cereal they poured from an average of 441 to 262 ml (1.9 to 1.1 cups) (P<0.0001; Table 1). Despite this reduction in volume selected, there was a significant increase in the weight and energy of cereal taken as flake size was reduced (P<0.0001; Table 1). In contrast, the amount of milk poured was relatively consistent, differing only for the smallest flake size (Table 1). Figure 1B shows that although subjects took more cereal energy as flake size was reduced, their estimates of the number of calories taken did not change (P=0.21). For the two cereals with the largest flakes, calorie estimates were fairly accurate, but for the two cereals with the smallest flakes, individuals significantly underestimated the calories taken (P<0.04).

Table 1.

Amounts of cereal and milk poured and consumed by 41 adults in a crossover study that tested the effects of reducing the flake size and volume of cereal on breakfast intake

| Cereal flake size (volume) | Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| 100% | 80% | 60% | 40% | ||

| mean ± standard error of the mean | P-value | ||||

| Cereal volume poured (ml) | 441 ± 26a | 404 ± 26a | 348 ± 19b | 262 ± 15c | <0.0001 |

| Cereal volume poured (cups) | 1.86 ± 0.11a | 1.71 ± 0.11a | 1.47 ± 0.08b | 1.11 ± 0.06c | <0.0001 |

| Cereal volume poured (% of standard cereal poured) |

100 ± 0.0a | 93.8 ± 3.6a | 82.0 ± 3.1b | 63.0 ± 3.1c | <0.0001 |

| Cereal weight poured (g) | 61.7 ± 3.7a | 70.6 ± 4.5b | 81.1 ± 4.4c | 91.5 ± 5.3d | <0.0001 |

| Cereal weight consumed (g) | 61.1 ± 3.7a | 69.3 ± 4.6b | 79.4 ± 4.3c | 83.9 ± 4.7c | <0.0001 |

| Cereal proportion consumed (% of weight poured) |

98.7 ± 0.5a | 97.9 ± 0.9a | 97.9 ± 0.8a | 92.3 ± 1.7b | 0.0002 |

| Milk weight poured (g) | 219 ± 16a | 213 ± 16a | 205 ± 15ab | 186 ± 13b | 0.003 |

| Milk weight consumed (g) | 189 ± 17 | 189 ± 16 | 187 ± 15 | 163 ± 12 | NSe |

| Milk proportion consumed (% of weight poured) |

82.9 ± 3.1 | 88.0 ± 2.5 | 90.6 ± 1.7 | 87.5 ± 2.4 | NSe |

Means for the same outcome with different letters are significantly different (P<0.04).

NS = nonsignificant P value.

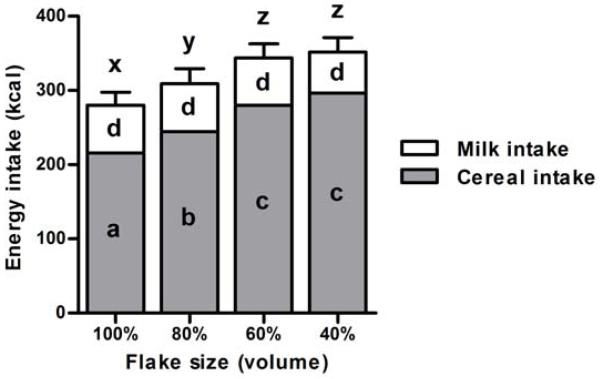

Participants ate most of the cereal that they served themselves: a mean of 98% of the weight they poured of the three cereals with the largest flakes (Table 1). Thus, as flake size was reduced from 100% to 60%, subjects poured and consumed a greater weight of cereal (P<0.0001); however, no further increase in weight was seen as flake size was reduced to 40%, since subjects ate a smaller proportion of what they took (92%). Consumption of milk and hot beverages did not vary significantly across meals (Table 1). Thus, decreasing cereal volume by reducing the size of individual pieces had a substantial effect on energy intake at breakfast (Figure 2), so that 81±12 kcal or 34±7% more energy was consumed with the most crushed cereal compared to the standard cereal. Despite the variation in energy intake, after-breakfast ratings of both hunger (mean 11±1 mm) and fullness (mean 72±2 mm) did not differ across meals (both P>0.24).

Figure 2.

This graph shows breakfast energy intake (mean ±SEM) of 41 adults in a crossover study that tested the effects of reducing the flake size and volume of cereal. For cereal intake and for breakfast intake, means with different letters are significantly different (P<0.02); for milk intake, there were no significant differences between means (P>0.08). Breakfast intake also included a small amount of energy from hot beverages, which did not differ across meals (mean 6±1 kcal; P=0.39).

Differences in the weight of cereal poured and consumed were not related to pre-breakfast hunger and fullness ratings, which were similar across meals (both P>0.19). Participants rated all versions of the cereal as similarly pleasant in taste (mean 67±1 mm; P=0.15), and while the most crushed cereal was less pleasant in appearance and texture than some of the others, none of the ratings of cereal characteristics were found to be significant covariates for either the weight of cereal poured or consumed (all P>0.39). Differences in subject characteristics such as age, sex, body mass index, dietary restraint, disinhibition, tendency toward hunger, and calorie estimation accuracy did not significantly affect the relationship between cereal volume and intake, nor were there significant differences across study weeks in the amounts taken or eaten.

Most previous studies of food volume have not separated the effects of volume from those of food weight; for example, in studies showing an effect of portion size on intake, volume and weight usually changed simultaneously.5,8,9 Two studies have tested the independent effect of volume on intake by varying the amount of air incorporated into a food, which affects volume but not weight. In one, when subjects were served two versions of an extruded snack differing in the amount of incorporated air, they consumed less weight and energy of the more-aerated snack.10 In another, adding air to increase the volume of a milkshake consumed as a first course reduced energy intake at the rest of the meal.11 In these studies, investigators served a fixed weight of food and thus did not assess how the variations in volume influenced subject’s self-selected portions of food. Other research has demonstrated that portion estimation is affected by food properties affecting volume such as the size of food pieces. For example, when subjects were asked to select an amount of French fries that matched a standard portion, they selected a similar volume but a lower weight of thin pieces than of thick pieces; however, the effect on food intake was not assessed.15-16 The present study is the first to systematically show that the volume of food independent of its weight affects both the amount selected and the amount eaten.

Variables that have been shown to affect the portion of food selected, such as the size and shape of the container in which food is offered17-20 or the bowl into which it is served,21 were controlled in the present study. The same weight of cereal was presented in a large opaque container and differences between the cereals were not evident until the cereal was poured into a standard-size bowl. Furthermore, since the same brand of cereal was used at all meals, there were no differences in ingredients or nutrient composition, and subject’s ratings indicated that the cereals were similar in taste. Thus, it seems likely that the amount of cereal taken was related to the perception of how the cereal filled the bowl. These results support the idea that intake is largely influenced by decisions made before eating begins22-23 and show that variations in volume can make it difficult to select an appropriate portion of food and to estimate the calories taken.

The variations in energy intake associated with changes in food volume are of particular interest since participants were screened to ensure that they ate breakfast cereal at least occasionally. Despite their familiarity with cereal, they did not fully compensate for food volume differences and thus consumed more calories of the smaller-flaked cereals than they thought. Individuals unfamiliar with a food would be likely to have even more difficulty responding to such volume changes. Further investigation of volume effects should be conducted among a wider range of subjects as well as using different types of foods. The effects seen here for flake size are likely to extend to the many other foods with properties that affect volume, including degree of aeration, cooking, and variations in the size and shape of pieces.

The findings of this study have implications for both portion selection and dietary advice. National guidelines for most food groups define recommended amounts in terms of volume (cups), but only a few adjustments are made for differences in food volume stemming from physical properties of food. For the Grains Group, the recommendations state that, in general, 1 cup of ready-to-eat cereal can be considered as 1 ounce-equivalent.3 For cereal with small pieces such as granola or crunchy types, however, a one-cup serving contains two to three ounces. If this increased weight per serving is combined with the typically higher energy density of granola and crunchy cereals, one cup can provide more than three times the calories as the same volume of flaked cereal. For cereals with small pieces, the recommended serving should be reduced to account for the uncharacteristically low volume, in the same way that the recommended serving is increased for voluminous foods such as puffed cereals3 and leafy greens2.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a physical property of food that influences volume independent of weight, specifically the size of individual pieces, affects the portion of food that people take, which in turn affects how much they eat. Even with familiar foods, individuals do not adjust sufficiently for variations in volume in order to select a portion with a consistent weight and energy content. Differences in food volume present a challenge not only to energy balance but also to advice on recommended portion sizes. Although it can be difficult to determine the volume of food that has pieces of variable size and shape, its impact on energy intake needs to be taken into consideration in providing dietary guidance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US Department of Agriculture . Food Groups Overview. Washington, DC: [Accessed December 3, 2013]. 2011. ChooseMyPlate.gov. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Agriculture . What counts as a cup of vegetables? Washington, DC: [Accessed December 3, 2013]. 2011. ChooseMyPlate.gov. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/vegetables_counts_table.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Agriculture . What counts as an ounce equivalent of grains? Washington, DC: [Accessed December 3, 2013]. 2011. ChooseMyPlate.gov. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/grains_counts_table.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolls BJ. Dietary strategies for weight management. In: Drewnowski A, Rolls BJ, editors. Obesity Treatment and Prevention: New Directions. Vol. 73. S. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 2012. pp. 37–48. Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kral TVE, Rolls BJ. Portion size and the obesity epidemic. In: Cawley J, editor. The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Obesity - the Causes and Correlates of Diet, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2011. pp. 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolls BJ. Dietary strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(1):70–79. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109991674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ. Properties of foods and beverages that influence energy intake and body weight. In: Coulston AM, Boushey CJ, editors. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press; London, England: 2008. pp. 469–481. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. The effect of large portion sizes on energy intake is sustained for 11 days. Obesity. 2007;15(6):1535–1543. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolls BJ, Castellanos VH, Halford JC, Kilara A, Panyam D, Pelkman CL, Smith GP, Thorwart ML. Volume of food consumed affects satiety in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67(6):1170–1177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osterholt KM, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Incorporation of air into a snack food reduces energy intake. Appetite. 2007;48(3):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Waugh BA. Increasing the volume of a food by incorporating air affects satiety in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(2):361–368. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(1):38–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service [Accessed June 7, 2013];USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 25. Nutrient Data Laboratory. Web site. http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl/

- 15.Wise A, Arregui-Fresneda I, Duncan L, Moalosi G. Visual perception of portion size. Ecol Food Nutr. 2008;47(2):126–134. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsay C, Wise A. Visual perception of portion size. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology. 2009;7:250–256. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piaget J. The Mechanisms of Perception. Routledge & Kegan Paul; London, England: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghubir P, Krishna A. Vital dimensions in volume perception: can the eye fool the stomach? Journal of Marketing Research. 1999;36(3):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wansink B. Environmental factors that increase the food intake and consumption volume of unknowing consumers. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:455–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchiori D, Corneille O, Klein O. Container size influences snack food intake independently of portion size. Appetite. 2012;58(3):814–817. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wansink B, van Ittersum K, Painter JE. Ice cream illusions bowls, spoons, and self-served portion sizes. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):240–243. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunstrom JM, Collingwood J, Rogers PJ. Perceived volume, expected satiation, and the energy content of self-selected meals. Appetite. 2010;55(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fay SH, Ferriday D, Hinton EC, Shakeshaft NG, Rogers PJ, Brunstrom JM. What determines real-world meal size? Evidence for pre-meal planning. Appetite. 2011;56(2):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]