Abstract

Rational

Viral myocarditis is a life-threatening illness that may lead to heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias. A major causative agent for viral myocarditis is the B3 strain of coxsackievirus, a positive-sense RNA enterovirus. However, human cardiac tissues are difficult to procure in sufficient enough quantities for studying the mechanisms of cardiac-specific viral infection.

Objective

This study examined whether human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) could be used to model the pathogenic processes of coxsackievirus-induced viral myocarditis and to screen antiviral therapeutics for efficacy.

Methods and Results

Human iPSC-CMs were infected with a luciferase-expressing coxsackievirus B3 strain (CVB3-Luc). Brightfield microscopy, immunofluorescence, and calcium imaging were utilized to characterize virally-infected hiPSC-CMs for alterations in cellular morphology and calcium handling. Viral proliferation in hiPSC-CMs was quantified using bioluminescence imaging. Antiviral compounds including interferon beta 1 (IFNβ1), ribavirin, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, and fluoxetine were tested for their capacity to abrogate CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs in vitro. The ability of these compounds to reduce CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs was consistent with reported drug effects in previous studies. Mechanistic analyses via gene expression profiling of hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc revealed an activation of viral RNA and protein clearance pathways after IFNβ1 treatment.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that hiPSC-CMs express the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, are susceptible to coxsackievirus infection, and can be used to predict antiviral drug efficacy. Our results suggest that the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc assay is a sensitive platform that can screen novel antiviral therapeutics for their effectiveness in a high-throughput fashion.

Keywords: Stem cell, cardiomyocyte, myocarditis, Coxsackie type B, drug screening

INTRODUCTION

Myocarditis is characterized by myocardial inflammation that can progress to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and heart failure1, 2. Upwards of 20% of all sudden cardiac deaths in young adults may be caused by myocarditis, which arises via systemic bacterial or viral infections3, 4. Viral myocarditis remains a difficult disease to diagnose definitively, partly because the preferred diagnostic method is invasive myocardial biopsy5. Group B coxsackieviruses are single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses belonging to the Enterovirus genus and may be implicated in 30–50% of all myocarditis cases6, 7. The B3 strain of coxsackievirus (CVB3) has been the most commonly used strain in animal and cellular models of viral myocarditis8. CVB3 proliferates rapidly within human cardiomyocytes, entering the cell via a transmembrane coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) that is differentially expressed on various cell types, is highly-expressed in cardiomyocytes, and is essential for mammalian cardiogenesis9–11. CAR also functions as an intercellular adhesion molecule and associates with extracellular matrix glycoproteins such as laminin and fibronectin12. Differential expression of CAR may determine tissue-specific susceptibility to CVB3 infection, and cardiac tissues highly express CAR during development and in DCM13–16. Following internalization in primary human cardiomyocytes, CVB3 can induce viral cytopathogenic effect and myofiber necrosis within hours10. Given the life-threatening consequences of cardiac viral infection, it is critical to further elucidate the mechanisms of CVB3-induced viral myocarditis.

Obtaining primary human cardiac tissues for research purposes requires invasive surgical procedures. Thus, these tissues are scarce and cannot be cultured easily in vitro, limiting their utility for studying cardiac disease mechanisms17. While animal models can partially recapitulate human cardiovascular disease phenotypes, they exhibit inter-species differences in heart rate, electrophysiology, and cardiogenesis18. However, with the advent of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), difficult-to-procure cell types, such as human cardiomyocytes, can now be mass-produced in vitro19, 20. These hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) could be used to investigate the pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms of acquired cardiac disorders such as viral myocarditis. While other cell types such as HEK293T and HeLa have been used to study coxsackievirus infection, these non-cardiac cells are not ideal for modeling cardiomyocyte infection in viral myocarditis21, 22. Other cardiac cells, such as HL-1 mouse atrial tumor cells, are immortalized, proliferative cells that are not reflective of adult human cardiomyocytes23. Thus, hiPSC-CMs are ideal cells for studying the mechanisms of coxsackievirus-induced viral myocarditis as they are non-immortalized human cardiomyocytes that can be mass-produced and express relevant ion channels and sarcomeric proteins found in adult human cardiomyocytes20. Because there are limited therapeutic options for eliminating coxsackievirus-induced infections, hiPSC-CMs could provide a novel platform for screening compounds aiming to treat diseases, such as viral myocarditis, that are caused by coxsackievirus infection24.

Here, we derived hiPSC-CMs to model CVB3-induced viral myocarditis. We studied CAR expression using immunofluorescence and quantitative gene expression assays and determined that, like primary cardiomyocytes, hiPSC-CMs express CAR and are susceptible to coxsackievirus infection. We also employed brightfield microscopy, immunofluorescence, and calcium imaging to characterize alterations in hiPSC-CM structure and function due to CVB3 infection. Finally, we utilized a luciferase-expressing CVB3 strain (CVB3-Luc) to quantify viral replication on hiPSC-CMs. This study represents the first time that hiPSC-CMs have been used to quantitatively assess the efficacy of antiviral compounds in reducing coxsackievirus proliferation on human cardiomyocytes, thus providing a new platform for screening novel antiviral therapeutics.

METHODS

An expanded Methods section is available in the Supplemental Materials.

Differentiation of hiPSC-CMs from hiPSCs

Lentiviral reprogramming was used to generate three hiPSC lines from skin fibroblasts of three healthy individuals in a 7-member family cohort25. An additional three hiPSC lines were generated with a previously-published Sendai virus reprogramming protocol using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from three healthy individuals26. These 6 hiPSC lines were differentiated into hiPSC-CMs using a 2D monolayer differentiation protocol and were maintained in a 5% CO2/air environment as previously published25, 27. Briefly, hiPSC colonies were dissociated with 0.5 mM EDTA into single-cell suspension and resuspended in E8 media (Life Technologies) containing 10 µM Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor (Sigma). Approximately 100,000 cells were replated into 6-well dishes pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Next, hiPSC monolayers were cultured to 85% cell confluency. Cells were then treated for 2 days with 6 µM CHIR99021 (Selleck Chemicals) in RPMI+B27 supplement without insulin to activate Wnt signaling and induce mesodermal differentiation. On day 2, cells were placed on RPMI+B27 without insulin and CHIR99021. On days 3–4, cells were treated with 5 µM IWR-1 (Sigma) to inhibit Wnt pathway signaling and induce cardiogenesis. On days 5–6, cells were removed from IWR-1 treatment and placed on RPMI+B27 without insulin. From day 7 onwards, cells were placed on RPMI+B27 with insulin until beating was observed. At this point, cells were glucose-starved for 3 days with RPMI (no glucose)+B27 with insulin to purify hiPSC-CMs, as cardiomyocytes can selectively metabolize fatty acids as a source of cellular energy28. Following purification, cells were cultured in RPMI+B27 with insulin. When replating hiPSC-CMs for downstream use, cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies) into a single-cell suspension and seeded on Matrigel-coated plates.

CVB3-Luc infections and antiviral treatments

Stocks from a previously-published CVB3-Luc strain expressing Renilla luciferase were stored at −80°C until needed29. IFNβ1 (Life Technologies), ribavirin (MP Biochemicals), PDTC (Sigma), and fluoxetine (Sigma) stocks were dissolved in water. Before CVB3-Luc infection, day 30–35 post-differentiation hiPSC-CMs were pretreated with antiviral compounds for 12 hours unless noted otherwise.

Bioluminescence imaging

Day 30–35 post-differentiation hiPSC-CMs were plated in RPMI+B27 with insulin on Matrigel at a density of 40,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate. At the time of CVB3-Luc infection, 6 µM Enduren extended duration coelenterazine (Promega) was added. Following infection, bioluminescence imaging was conducted using a Xenogen IVIS 100 Imaging System. Living Image software (Perkin Elmer) was used for image analysis.

Ca2+ imaging

Dissociated day 30–35 post-differentiation hiPSC-CMs were reseeded in Matrigel-coated 8-well Lab Tek II chambers (Nalge Nuc International) and were treated with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM and 0.02% Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes) in Tyrode’s solution for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed with Tyrode’s solution afterwards. Ca2+ imaging was conducted using a Zeiss LSM 510Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG) and analyzed using Zen imaging software. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients were obtained at 37°C using a single-cell line scan mode.

Cell metabolism and viability assays

WST-1 reagent (Abcam) was used to determine hiPSC-CM metabolism and viability following antiviral treatment. After 48-hour treatment with antiviral compounds, 10 µL of WST-1 reagent was added to 100 µL RPMI+B27 with insulin on day 30–35 post-differentiation hiPSC-CMs. After 24 hours, a microplate reader (Promega) was used to quantify conversion of tetrazolium salt WST-1 into formazan dye at 420–480 nm absorbance. Absorbance reading correlated directly with cell viability.

Gene expression and immunocytochemistry

For qRT-PCR, RNA was extracted with the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) and real-time PCR was conducted on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System. Primers are listed in Online Table I. For additional gene expression analysis, a GeneChip® Human Gene 2.0 ST DNA Microarray was used (Affymetrix). Immunostaining was performed according to previous protocols23. Imaging was performed using a DMIL–LED microscope (Leica Microsystems) or a Zeiss LSM 510Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG) using Zen imaging software.

Statistical Methods

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were conducted via student’s t-test with significant differences (*) defined by p<0.05. For microarray results, multiple p-value comparisons were made using a one-way between-subject ANOVA (p<0.05) using Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) 2.0 software. Microarray data was deposited under NIH GEO (GSE57781).

RESULTS

Expression of cardiomyocyte markers in hiPSC-CMs

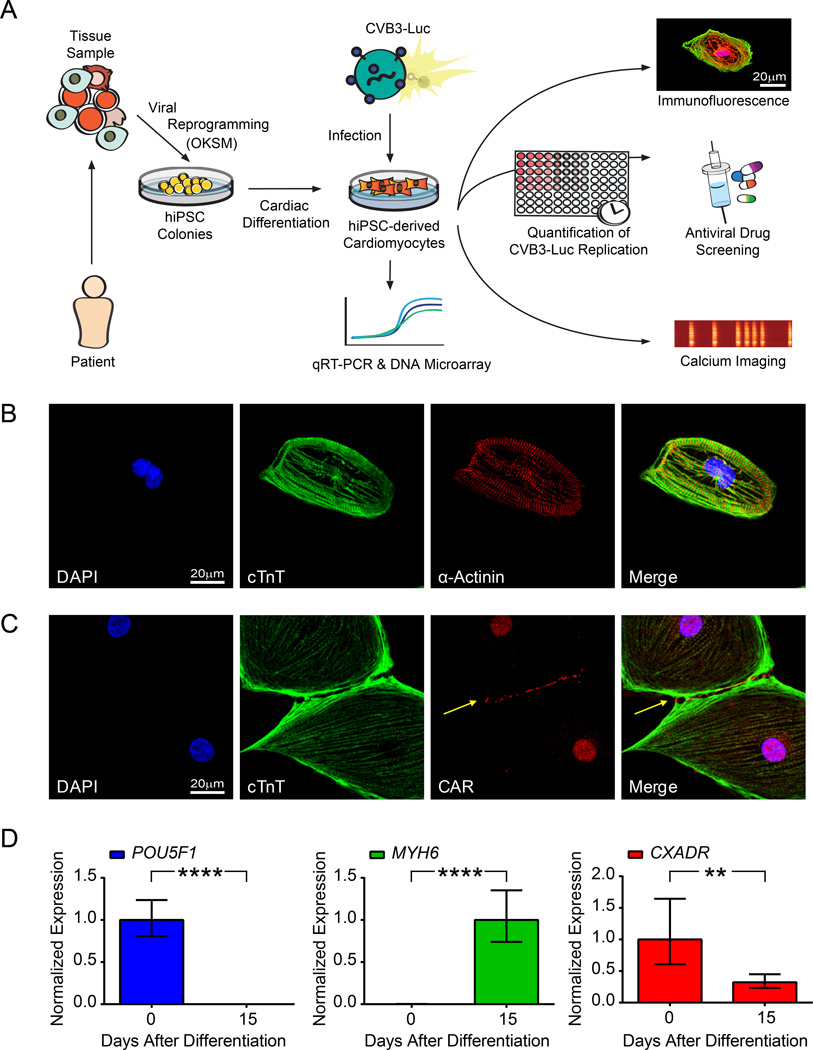

Undifferentiated hiPSCs expressed standard pluripotency markers as shown previously (Online Figure I)25. We produced hiPSC-CMs from hiPSCs using a monolayer-based cardiac differentiation protocol27. We achieved upwards of 90% differentiation efficiency and generated spontaneously contracting sheets of hiPSC-CMs (Online Movie I). Next, hiPSC-CMs were purified via glucose deprivation and replated for downstream analyses (Figure 1A). Cells exhibited regular beating patterns after replating (Online Movie II). Using immunofluorescence, we confirmed that hiPSC-CMs express cardiac-specific, sarcomeric proteins. Expression of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) showed a striated pattern intercalated with α-actinin expression along sarcomeric Z-lines (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. hiPSC-CMs express intracellular sarcomeric proteins and CAR at cell-cell junctions.

A, Flow chart illustrating study design. Skin fibroblast samples obtained from 3 healthy individuals in a 7-member patient family cohort were reprogrammed using lentiviral vectors expressing OKSM. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were also isolated from 3 additional healthy individuals and reprogrammed using a Sendai virus vector expressing OKSM. Subsequent hiPSC colonies were differentiated into hiPSC-CMs. Downstream analyses such as immunofluorescence, calcium imaging, and antiviral drug efficacy testing were then conducted on hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc. B, Confocal microscopy images of single hiPSC-CMs demonstrates the presence of sarcomeric proteins such as cTnT and α-actinin. C, Confocal microscopy demonstrates the presence of CAR at hiPSC-CM intercellular junctions (arrow). D, qRT-PCR of hiPSC-CMs at days 0 and 15 following cardiac differentiation reveals a decrease in POU5F1 expression (left), an increase in MYH6 expression (middle), and a decrease in CXADR expression (right). ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001

Expression of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor

Immunofluorescence revealed that hiPSC-CMs expressed the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) at cell-cell junctions (Figure 1C). Nuclear stain for CAR in CMs has been previously reported and may represent antibody cross-reactivity with a nuclear antigen30. CAR is also expressed in hiPSCs, suggesting that both hiPSCs and hiPSC-CMs are susceptible to coxsackievirus infection (Online Figure I, Online Figure II). In HL-1 cells, CAR is also expressed at points of cell-cell contact (Online Figure III). We used qRT-PCR to confirm significant downregulation of pluripotency gene expression (POU5F1) and significant upregulation of cardiac-specific structural gene expression (MYH6) in hiPSC-CMs after 15 days of cardiac differentiation (Figure 1D). We also observed an approximately two-fold reduction in expression of CXADR, encoding for CAR, after 15 days of cardiac differentiation (Figure 1D). CXADR expression in hiPSC-CMs is 30-fold less than primary adult human left ventricular myocardium sample (Online Figure IV). However, CXADR expression in hiPSC-CMs is 10-fold higher than in HL-1 mouse cardiac cells (Online Figure IV). These results demonstrate that hiPSC-CMs express CAR along with cardiac-specific markers.

Characterization of hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc

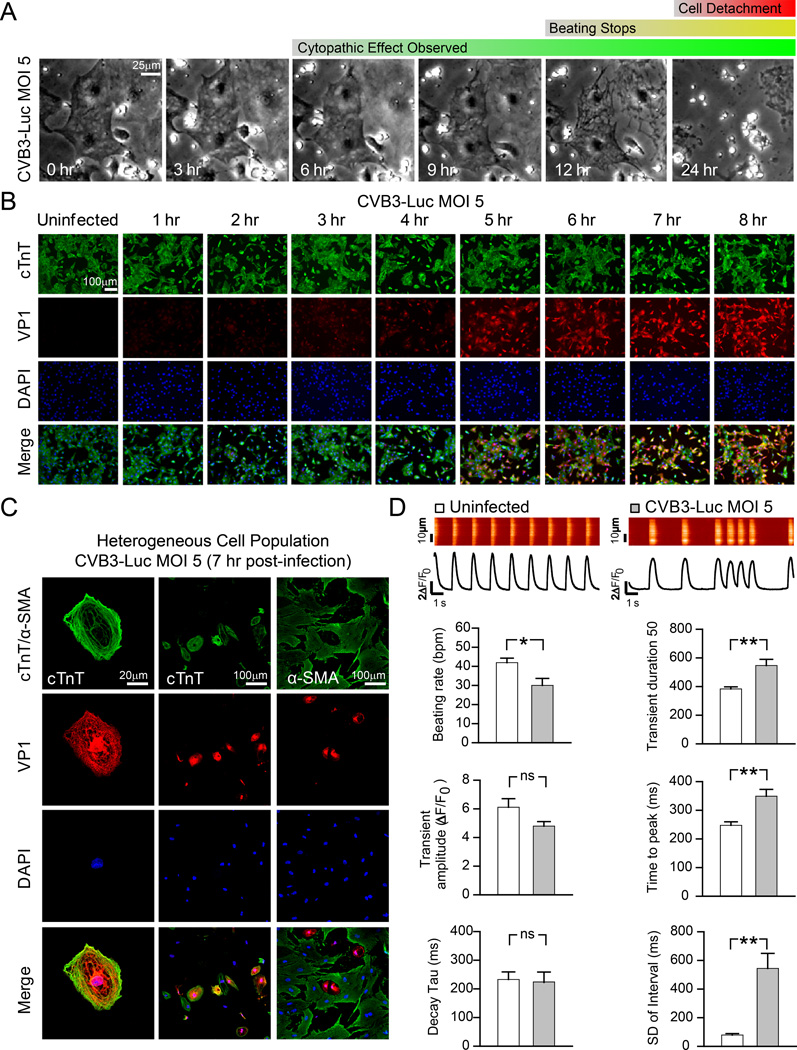

Purified hiPSC-CMs were infected with a B3 strain of coxsackievirus expressing Renilla luciferase (CVB3-Luc). CVB3-Luc gene expression strongly correlated to luciferase luminescence in infected hiPSC-CMs, suggesting that luminescence could be used as a direct measure for CVB3-Luc proliferation (Online Figure V). At multiplicity of infection (MOI) 5, virally-induced cytopathic effect appeared at 6–8 hours post-infection, corresponding to the completion of the CVB3 replication cycle31. We did not observe a difference in time to cytopathic effect onset between our 6 hiPSC-CM lines at CVB3-Luc MOI 5 (Online Figure VI). Complete cell detachment was apparent at 24 hours post-infection (Figure 2A). Starting at 6 hours post-infection with CVB3-Luc MOI 5, cells displayed irregular beating patterns that became increasingly erratic over time, culminating in the eventual cessation of beating after approximately 12 hours of infection (Online Movies III–IV). Onset of cytopathic effect in a purified population of hiPSC-CMs corresponded to increased expression of VP1, a component of the viral capsid (Figure 2B)31. Notably, hiPSCs were also susceptible to CVB3-Luc infection and displayed an increase in VP1 expression after infection (Online Figure VII). Only a small proportion of HL-1 cells in a homogenous population expressed VP1 after CVB3 infection, as described previously (Online Figure III)32. In a heterogeneous, unpurified population of hiPSC-CMs after a low-efficiency cardiac differentiation, cTnT+ hiPSC-CMs were more susceptible to CVB3-Luc infection than non-CM, α-SMA+, mesenchymal cells (Figure 2C). Calcium imaging of cells (n=12) infected with CVB3-Luc at MOI 5 for 7 hours showed a significant reduction in beating rate and increases in calcium transient duration, time to transient peak, and standard deviation of transient intervals, suggesting that CVB3-Luc infection results in disrupted intracellular calcium handling in hiPSC-CMs (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that hiPSC-CMs are highly susceptible to coxsackievirus infection and that viral infection causes detrimental alterations in hiPSC-CM structure and function.

Figure 2. hiPSC-CMs are susceptible to infection by CVB3-Luc and display irregular intracellular calcium handling phenotypes during infection.

A, Brightfield images of hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5) show the progression of cellular cytopathic effect due to viral infection over 24 hours. B, Immunofluorescence images of hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5) illustrate increasing VP1 expression in a homogeneous population of cTnT+ hiPSC-CMs over 8 hours following infection. C, Immunofluorescence images of a heterogeneous, differentiated cell population illustrates VP1 expression in cTnT+ hiPSC-CMs (left, middle), but not in non-CM, α-SMA+, mesenchymal cells (right) 7 hours after infection with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5). D, Single-cell Ca2+ imaging of uninfected hiPSC-CMs and hiPSC-CMs 7 hours after infection with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5). * p<0.05; ** p<0.01

Quantification of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs

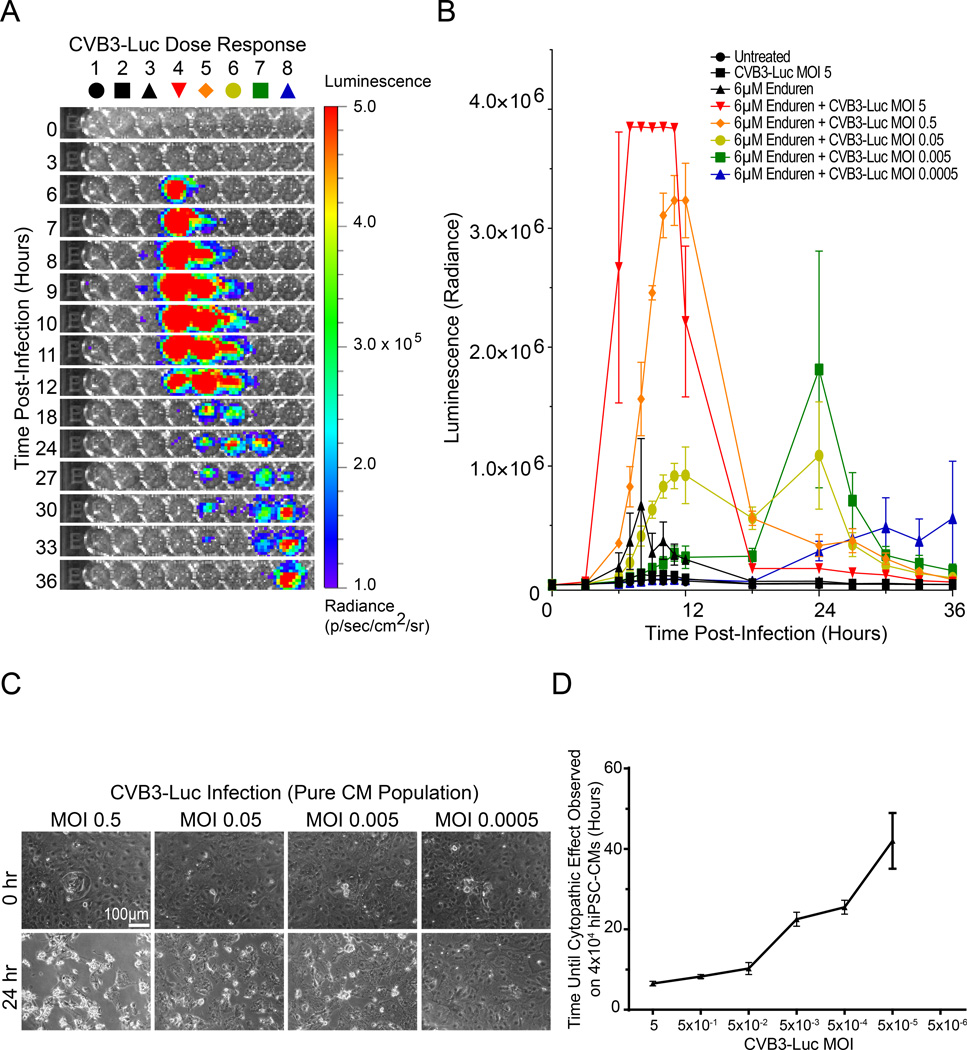

We next utilized bioluminescence imaging to quantify CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs. Purified hiPSC-CMs were infected with decreasing MOI of CVB3-Luc in the presence of Enduren, an extended-duration coelenterazine (Figure 3A). CVB3-Luc proliferation was quantified based on bioluminescence intensity (radiance), corresponding to the amount of luciferase, and thus virus, being produced. At MOI 5, bioluminescence signal spiked at 6 hours post-infection, corresponding to the completion of the first viral replication cycle. Signal intensity increased until 12 hours post-infection, at which point bioluminescence diminished due to cell death (Figure 3A, 3B). At lower MOIs, there was a delay in time to peak of bioluminescence signal, likely because multiple CVB3-Luc replication cycles were required before the luciferase signal could be detected. For example, at MOI 5×10−4, approximately 24 hours elapsed before onset of the bioluminescence signal. Treatment of hiPSC-CMs with decreasing MOI of CVB3-Luc also resulted in concentration-dependent reduction in pathologic phenotype after 24 hours and a delay in cytopathic effect onset (Figure 3C). MOI 5×10−5 CVB3-Luc infection on 40,000 hiPSC-CMs still led to delayed well-wide cytopathic effect and complete hiPSC-CM cell death, suggesting that a single digit number of viral particles is able to propagate the CVB3-Luc infection in a well of hiPSC-CMs (Figure 3D, Online Figure VIII). CVB3-Luc proliferation was substantially lower in HL-1 cells in comparison to hiPSC-CMs (Online Figure III). These results demonstrate that the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc platform can be used to quantify viral replication in human cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. CVB3-Luc infection of hiPSC-CMs allows for quantification of viral proliferation using bioluminescence imaging.

A, Representative 96-well plate containing hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc visualized over 36 hours using bioluminescence imaging. A decrease in MOI corresponds with a delay in signal onset. B, Quantification of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs. A decrease in MOI corresponds to a delay in bioluminescence signal and viral proliferation. C, Brightfield images at 0 and 24 hours post-infection of hiPSC-CMs infected with decreasing amounts of CVB3-Luc. D. Quantification of time of onset for CVB3-Luc cytopathic effect at decreasing MOIs on a pure population of 40,000 hiPSC-CMs.

Antiviral drug treatments abrogate CVB3-Luc proliferation

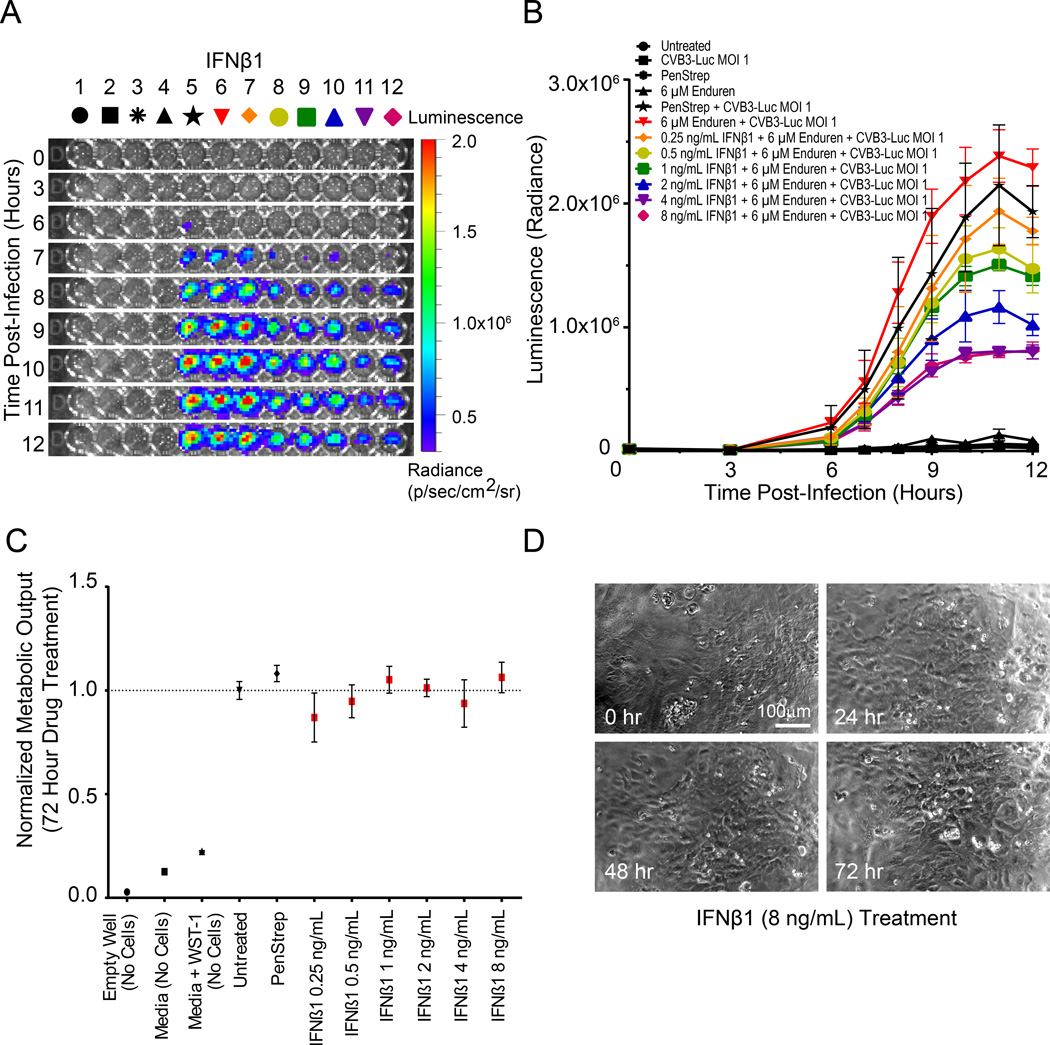

We utilized the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc system to test the efficacy of antiviral compounds in abrogating viral proliferation in vitro (Table 1). We first treated hiPSC-CMs with interferon beta 1 (IFNβ1), as IFNβ1 treatment is able to eliminate cardiotropic viruses in patients with myocarditis and reduce CVB3 proliferation in hESC-CMs in vitro33, 34. We observed a concentration-dependent reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation after 12 hour pretreatment with 0.5–8 ng/mL IFNβ1 (Figure 4A). At 8 ng/mL IFNβ1, we observed a greater than 50% reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs (Figure 4B). However, IFNβ1 was unable to significantly reduce CVB3-Luc proliferation on HL-1 cells (Online Figure IX). When IFNβ1 was added concurrently with the virus, it was not as effective in reducing CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs, perhaps because the 12 hour pre-treatment allows time for the activation of IFNβ1 downstream pathways and expression of viral clearance proteins such as RNase L and PKR (Online Figure X)35. As a negative control, the antibiotic PenStrep did not cause a significant reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs. Treatment with up to 8 ng/mL IFNβ1 alone did not cause significant alteration in hiPSC-CM cellular metabolism when measured with a WST-1 colorimetric assay (Figure 4C). IFNβ1 treatment at 8 ng/mL also did not induce visible alterations in hiPSC-CM monolayer morphology or beating patterns, suggesting that IFNβ1 reduces CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs without inducing cardiotoxicity (Figure 4D).

Table 1.

Antiviral compounds utilized to abrogate CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs

| Antiviral Compound |

Mechanism of Antiviral Action |

Reduced CVB3- Luc Proliferation on hiPSC-CMs? |

Cardiotoxicity Observed on hiPSC-CMs? |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon Beta 1 (IFNβ1) |

Activation of downstream viral RNA and protein clearance pathways |

Yes | No | Scassa et al., 201133; Kuhl et al., 200333 |

| Ribavirin | Nucleoside inhibitor of viral RNA synthesis |

Yes | No | Heim et al., 199736; Crotty et al., 200045 |

| Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) |

Inhibition of ubiquitin- proteasome proteolysis |

Yes | No | Si et al., 200535 |

| Fluoxetine | Mechanism unclear | 4 µM, 8 µM | Yes | Zuo et al., 201237 |

Figure 4. IFNβ1 treatment reduces CVB3-Luc proliferation on infected hiPSC-CMs in a concentration-dependent fashion.

A, Representative 96-well plate containing hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc and pre-treated with IFNβ1 for 12 hours, visualized over 12 hours using bioluminescence imaging. B, Quantification of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs pretreated with IFNβ1. C, WST-1 assay quantifying cellular metabolic output and viability following treatment with increasing amounts of IFNβ1. D, Stills from videos of hiPSC-CMs treated with 8 ng/mL IFNβ1 for up to 72 hours. These hiPSC-CMs continue beating after 72 hours of IFNβ1 treatment.

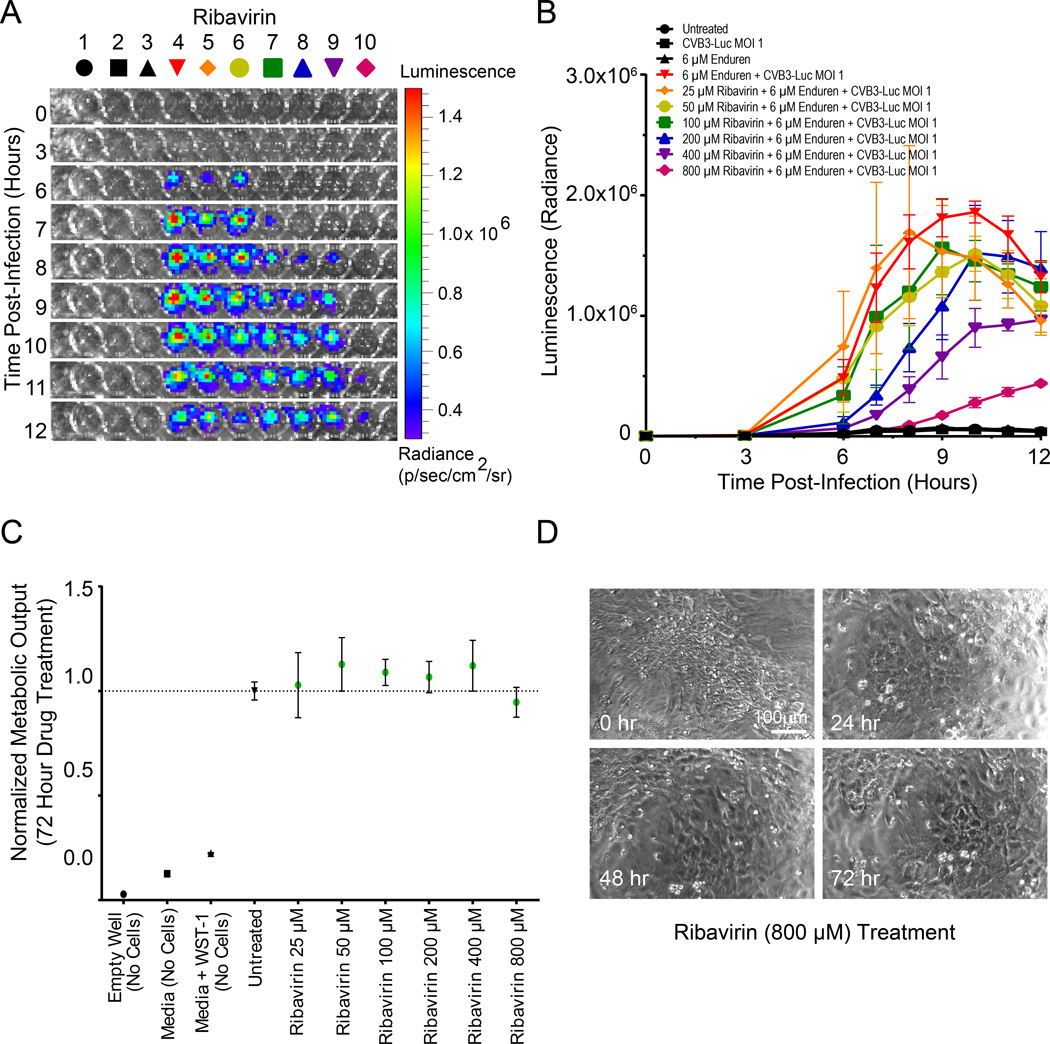

Ribavirin is a nucleoside inhibitor that inhibits viral RNA synthesis36. We observed a concentration-dependent reduction of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc after 12 hour pre-treatment with 25–800 µM ribavirin (Figure 5A). Pre-treatment with 800 µM ribavirin caused an approximately 50% reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs (Figure 5B). Similarly, ribavirin significantly reduced CVB3-Luc proliferation on HL-1 cells (Online Figure IX). Ribavirin was also moderately effective in reducing CVB3-Luc proliferation in hiPSC-CMs and HL-1 cells when added concurrently with CVB3-Luc, perhaps because as a small molecule compound, it is immediately able to function as a nucleoside inhibitor to reduce viral RNA transcription (Online Figure X). Ribavirin treatment up to 800 µM did not cause significant alterations in hiPSC-CM metabolic output, as measured by WST-1 assay (Figure 5C), or any visible detrimental effects to hiPSC-CM morphology or beating patterns (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Ribavirin treatment reduces CVB3-Luc proliferation on infected hiPSC-CMs in a concentration-dependent fashion.

A, Representative 96-well plate containing hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc and pretreated with ribavirin for 12 hours, visualized over 12 hours using bioluminescence imaging. B, Quantification of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs pretreated with ribavirin. C, WST-1 assay quantifying cellular metabolic output and viability following treatment with increasing amounts of ribavirin. D, Stills from videos of hiPSC-CMs treated with 800 µM ribavirin for up to 72 hours. These hiPSC-CMs continue beating after 72 hours of ribavirin treatment.

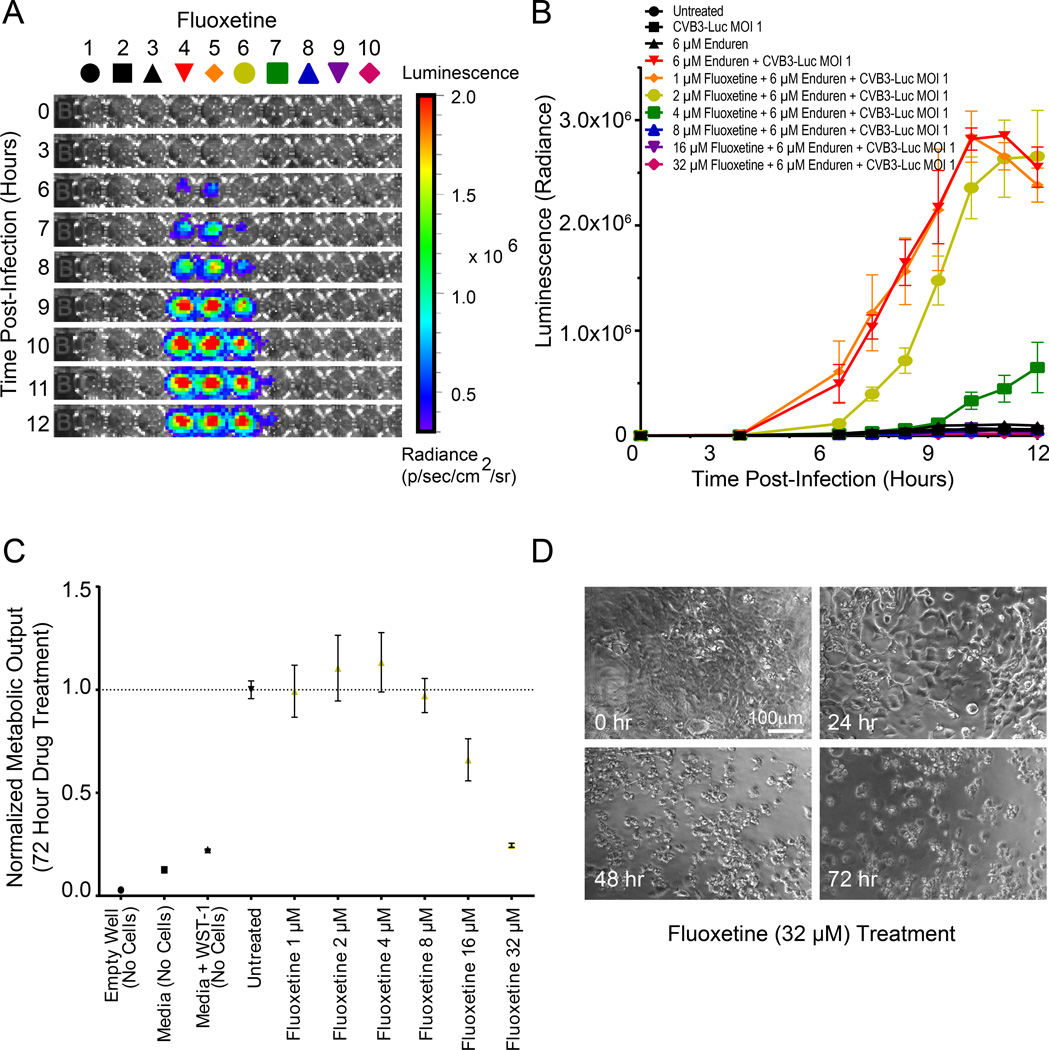

Next, we tested the effect of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in reducing CVB3-Luc replication. Fluoxetine is an effective inhibitor of coxsackievirus replication in HeLa cells37. We treated hiPSC-CMs with fluoxetine at concentrations ranging from 1–32 µM and observed that it had no significant effect in reducing CVB3-Luc proliferation at 1–2 µM (Figure 6A–6B). However, at 4–8 µM fluoxetine, we observed a significant drop in CVB3-Luc proliferation with no cardiotoxicity observed at these concentrations (Figure 6B–6C). At 16 µM and above, fluoxetine was visibly toxic to hiPSC-CMs and resulted in decreased hiPSC-CM metabolic output and significant cell death (Figure 6C–6D).

Figure 6. Fluoxetine treatment reduces CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs at select concentrations but exhibits cardiotoxicity.

A, Representative 96-well plate containing hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc and pretreated with fluoxetine for 12 hours, visualized over 12 hours using bioluminescence imaging. B, Quantification of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs pretreated with fluoxetine. Note that at low concentrations of fluoxetine (1–2 µM), there is no significant decrease in CVB3-Luc proliferation. At 4–8 µM fluoxetine, a significant decrease in viral proliferation is observed. At higher concentrations of fluoxetine (16–32 µM), there is complete abrogation of CVB3-Luc proliferation, but this is because of cell death limiting viral proliferation, as shown in C. C, WST-1 assay quantifying cellular metabolic output and viability following treatment with increasing amounts of fluoxetine. Note that concentrations of fluoxetine at 16 µM and above significantly reduce cell metabolism and viability. D, Stills from videos of hiPSC-CMs treated with 32 µM fluoxetine for up to 72 hours, demonstrating fluoxetine toxicity.

Finally, we tested the antiviral efficacy of the antioxidant pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), which reduces CVB3 replication through inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolysis pathway38. PDTC also inhibits the activation of 3Dpol, a viral RNA polymerase39. We observed a concentration-dependent reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation after 12 hour pretreatment of hiPSC-CMs with 25–800 µM PDTC (Online Figure XI). Pretreatment with 800 µM PDTC caused a significant reduction in CVB3-Luc proliferation (Online Figure XI). PDTC significantly reduced CVB3-Luc proliferation on HL-1 cells (Online Figure IX). PDTC was also highly effective in reducing CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs and HL-1 cells when added concurrently with CVB3-Luc or even after viral infection, reflective of its ability as a small molecule compound to rapidly inhibit activation of 3Dpol and stymie viral RNA transcription (Online Figure IX). When quantified using a WST-1 assay, higher concentrations of PDTC led to increased hiPSC-CM metabolic output (Online Figure XI). PDTC treatment for 72 hours at 800 µM did not cause a visible detrimental alteration in hiPSC-CM morphology or beating patterns (Online Figure XI). Taken together, these results show that the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc system can be used to screen for the functional efficacy and potential cardiotoxicities of antiviral compounds in vitro.

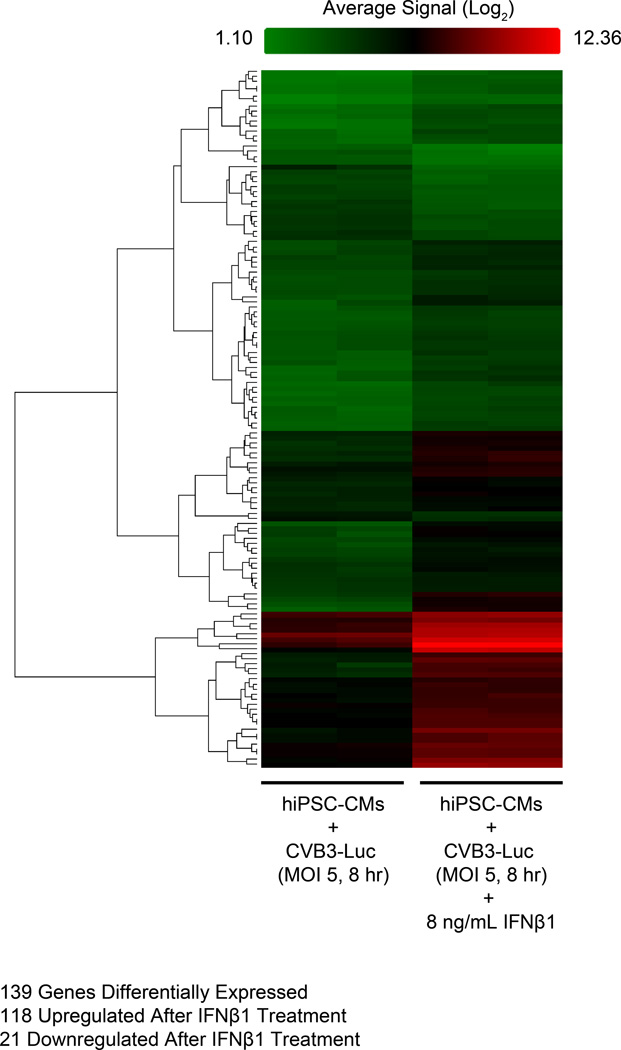

hiPSC-CMs provide mechanistic insight into IFNβ1-induced viral clearance pathways

We next assessed the specific molecular mechanisms by which hiPSC-CMs are able to clear viral mRNA and proteins to reduce coxsackievirus proliferation. We pretreated hiPSC-CMs with 8 ng/mL IFNβ1 for 12 hours and subsequently infected cells with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5) for 8 hours. Cells were then harvested for gene expression analysis using an Affymetrix DNA microarray. We observed that 139 genes were differentially expressed between infected hiPSC-CMs that did or did not receive IFNβ1 (Figure 7). Notably, IFNβ1 treatment significantly increased the expression of 22 genes previously implicated as mediators of viral clearance pathways (p < 1.605E-31) (Online Table II). These genes encode proteins that assist with a diverse range of antiviral functions such as ribonuclease activation, viral mRNA degradation, viral capsid protein degradation, viral particle sequestration, and interferon signal transduction40. These results suggest that in hiPSC-CMs, IFNβ1 treatment activates a network of downstream antiviral genes that reduce CVB3-Luc proliferation following infection.

Figure 7. Treatment with IFNβ1 leads to activation of interferon response pathways and viral clearance mechanisms in hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc.

Heat map showing rows of differentially expressed genes (n=139) following IFNβ1 treatment in hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3-Luc. Cells were pretreated with IFNβ1 for 12 hours prior to infection with CVB3-Luc (MOI 5) for 8 hours. Two samples were collected for each experimental condition. For the heat map, red indicates high gene expression, black indicates moderate gene expression, and green indicates low gene expression. 118 genes were upregulated and 21 were downregulated after IFNβ1 treatment. Of the 118 upregulated genes, 22 are known regulators of viral mRNA and protein clearance pathways (Online Table II).

DISCUSSION

Viral myocarditis is a disease for which there remains no effective antiviral treatment. Our results suggest that hiPSC-CMs can be used to study the mechanisms of CVB3-induced viral myocarditis. Notably, hiPSC-CMs express CAR and are susceptible to coxsackievirus infection. We observed a downregulation in CAR expression over a 15-day differentiation from hiPSCs to hiPSC-CMs, and previous studies have also illustrated that CAR mRNA expression decreases after 14 days of hESC to hESC-CM differentiation using embryoid body differentiation protocols33. Adult cardiac tissues exhibit lower CAR mRNA levels than embryonic cardiac tissues, which is understandable given CAR’s established role for promoting proper embryonic cardiogenesis via maintaining myofibril integrity15, 16, 30. However, we found that CAR expression is significantly lower in hiPSC-CMs in comparison to adult human left ventricular myocardium, perhaps reflecting the previously-observed functional immaturity of hiPSC-CMs41.

Cardiomyocytes can be infected by CVB3 and undergo apoptosis following completion of the CVB3 replication cycle33, 42. Following CVB3 internalization in CMs, viral protease 2A cleaves dystrophin, which connects the cardiomyocyte cytoskeleton with the extracellular matrix43. This could impair the mechanical transduction of force normally generated by the sarcomeres. Cleavage of dystrophin also disrupts cell membrane integrity, allowing for efficient release of newly created CVB3 viral particles43. Increased cell membrane permeability likely causes leakage of intracellular ions such as K+, Na2+, and Ca2+ that maintain membrane potential and propagate the cardiac action potential necessary for normal cardiomyocyte excitation-contraction coupling. This interplay between viral protease-mediated disruption of intracellular structural proteins and subsequent loss of cell membrane integrity, combined with the viral load created during the CVB3 replication cycle, likely results in the irregular beating, abnormal calcium transients, and eventual cessation of beating that we observed following CVB3 infection in hiPSC-CMs. Additionally, VP1, a component protein of the CVB3 capsid, shares up to 40% homology with cardiac myosin, and thus, antibodies against VP1 can cross-react with myosin44. Indeed, we observed the VP1 stain intercalating with the cTnT stain in the sarcomere. In spite of cross-reactivity, our VP1 antibody detects significant viral replication-induced increase in VP1 expression over time. We also observed a delayed, well-wide cytopathic effect by infecting 40,000 hiPSC-CMs with MOI 5×10−5 CVB3-Luc, suggesting that a single digit number of viral particles (approximately 2 in a well of 40,000 hiPSC-CMs) is able to propagate the viral infection across the entire well of hiPSC-CMs. This indicates that hiPSC-CMs are extremely susceptible to coxsackievirus infection.

There is a shortage of treatments for combating coxsackievirus infections and CVB3-induced myocarditis. Interferons have shown potential for eliminating cardiotropic viruses in vivo and in vitro and for improving ventricular function in patients with chronic myocarditis10, 33, 34, 36. Other compounds have shown modest effects in reducing CVB3-proliferation by interfering with viral capsid function24. However, none of these therapies has received FDA approval, and thus, there is significant interest in finding safe and effective antiviral compounds for treating coxsackievirus infection and CVB3-induced myocarditis. The advantage of using hiPSC-CMs instead of commonly-used cell lines, such as HEK 293T or HeLa cells, for antiviral drug screening is that hiPSC-CMs are more representative structurally and physiologically of the cardiac cell populations damaged during CVB3-induced myocarditis. Additionally, we believe that hiPSC-CMs are superior to HL-1 cardiac cells for modeling CVB3 infection on cardiomyocytes and for antiviral drug screening. CXADR expression in hiPSC-CMs is substantially higher than in HL-1 cells and is also closer to CXADR levels found in primary human cardiac tissue. CVB3-Luc proliferates in hiPSC-CMs at a significantly higher level than in HL-1 cells. IFNβ1 was unable to reduce CVB3-Luc proliferation on HL-1 cells, suggesting that IFNβ1-mediated antiviral response pathways may be significantly altered in these cells. These discrepancies between hiPSC-CMs and HL-1s are likely because HL-1 cells are an immortalized mouse cardiac line derived from a tumor lineage, and therefore, may not be as useful as hiPSC-CMs for recapitulating adult human cardiomyocyte gene expression, viral infection, and drug responses. Testing novel therapeutics on hiPSC-CMs also allows for the assessment of potential cardiotoxicities and drug-induced arrhythmias, which are leading causes of drug withdrawal from the pharmaceutical market45.

We employed CVB3-Luc to quantify the ability of a select group of compounds to reduce and delay coxsackievirus replication on hiPSC-CMs without inducing visible cardiotoxicity (Table 1). IFNβ1 was able to abrogate CVB3-Luc proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner and at very low concentrations, as demonstrated previously33. Using a DNA microarray, we found that IFNβ1 reduces viral proliferation by priming hiPSC-CMs against viral infection and activating multiple genes associated with viral RNA and protein clearance (Figure 7, Online Table II)40. In infected hiPSC-CMs treated with IFNβ1, we detected a ten-fold upregulation in the expression of OAS1, which encodes for an activator of antiviral ribonuclease L (RNase L)46. Additionally, we observed a five-fold upregulation in the expression of EIF2AK2, which encodes for protein kinase R (PKR), an inhibitor of viral mRNA translation that acts by phosphorylating the eukaryotic transcription initiation factor (EIF2)46. Ribavirin and PDTC were also effective in inducing a concentration-dependent reduction of CVB3-Luc proliferation on hiPSC-CMs, as they are well-established inhibitors of viral replication38, 47. Importantly, IFNβ1, ribavirin, and PDTC did not induce significant cardiotoxic effects on hiPSC-CMs. Interestingly, PDTC caused an increase in hiPSC-CM metabolic output as measured by WST-1 assay, which we attribute to an off-target, PDTC-induced hyperactivation of mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzymes that are required to cleave WST-1 substrate into formazan dye. We observed significant hiPSC-CM death following treatment with high concentrations of fluoxetine, which in our assay reduced CVB3-Luc proliferation at 4–8 µM. Fluoxetine overdose-induced arrhythmias have been reported previously but not cardiac cell death, as we have shown here48. Although the aforementioned compounds were successful in reducing and delaying viral proliferation, we observed that a single digit number of viral particles may be sufficient to propagate CVB3-Luc infection on an entire well of hiPSC-CMs, based on results from Figure 3D and Online Figure XIII. Thus, we confirmed the antiviral properties of three compounds and the potential cardiotoxicity of a fourth compound using the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc system. We envision that this system could be utilized in a high-throughput manner to screen for novel, non-cardiotoxic, antiviral therapeutics.

In summary, we have for the first time used hiPSC-CMs to model the mechanisms of viral myocarditis. Our results suggest that hiPSC-CMs express the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor needed for CVB3 internalization and are susceptible to infection by CVB3. Gene networks known to be associated with viral mRNA and protein clearance are also activated following antiviral treatment in hiPSC-CMs infected with CVB3. Additionally, the hiPSC-CM/CVB3-Luc system can be used to screen for antiviral compound efficacy. Ultimately, we believe that hiPSC-CMs represent a powerful tool for modeling disease mechanisms and for drug discovery purposes.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Viral myocarditis is a debilitating condition that can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure.

Viral myocarditis can be caused by the B3 strain of coxsackievirus (CVB3), a common human pathogen that can rarely infect the heart and cause a life-threatening medical situation.

It is difficult to obtain human cardiac tissues with which to study the mechanisms of cardiac viral infection, but thanks to recent discoveries in stem cell biology, we can now make an unlimited number of human heart cells (cardiomyocytes) from a patient’s own skin cells.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

By acting as a model for true human heart tissue, human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) can be used to study the mechanisms of viral myocarditis.

These hiPSC-CMs express the proteins needed for CVB3 to enter the cardiomyocyte, and as a result, CVB3 can invade the cell and replicate rapidly within it.

A genetically-modified strain of CVB3 can be used in conjunction with hiPSC-CMs to quantify viral replication, and thus, this system can be used to test for the efficacy of antiviral compounds in reducing viral proliferation on human cardiomyocytes.

Viral myocarditis is a life-threatening cardiac disease that arises when the heart is infected by a virus such as CVB3. However, it is difficult to obtain human heart tissues with which to study the mechanisms of this disease because cardiac biopsies are invasive and expensive. Recent advances have allowed for the mass production of human heart cells from a patient’s own skin or blood samples. Using this hiPSC-CM technology, we were able to study the mechanisms of CVB3 infection on human cardiomyocytes. We found that hiPSC-CMs express the coxsackievirus receptor needed to internalize CVB3, and hiPSC-CMs are highly susceptible to CVB3 infection because the virus is able to proliferate rapidly and destroy the cells in a matter of hours. Notably, we used hiPSC-CM technology in conjunction with a genetically-modified strain of CVB3 that expresses luciferase, a bioluminescent protein. This allowed us to quantify viral proliferation on hiPSC-CMs and screen for the antiviral efficacy of a panel of antiviral compounds. The CVB3/hiPSC-CM system that we established here could serve as a platform for discovering novel antiviral compounds that can effectively treat patients suffering from viral myocarditis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frank van Kuppeveld (Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, University of Utrecht) for providing the CVB3-Luc plasmid from which the CVB3-Luc virus was produced. We thank Karim Majzoub for his assistance with viral primer design and proliferation assays. We thank Bhagat Patlolla for his help with obtaining primary human left ventricular tissue samples.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

We gratefully acknowledge funding support from the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 13PRE15770000, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program DGE-114747 (AS), NIH Innovator Award DP2 OD004411, NIH U01 HL099776, CIRM RB3-05129 (SMW), and Leducq Foundation, AHA Established Investigator Award, NIH R01 HL113006, NIH U01 HL099776 (JCW).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAR

coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor

- cTnT

cardiac troponin T

- CVB3

coxsackievirus B3

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- hESC-CM

human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte

- hiPSC-CM

human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte

- IFNβ1

interferon beta 1

- LV

left ventricle

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- MYH6

myosin heavy chain 6, alpha

- OKSM

Oct4, Klf, Sox2, c-Myc

- PDTC

pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper LT. Myocarditis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:1526–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dec GW, Jr, Palacios IF, Fallon JT, Aretz HT, Mills J, Lee DC, Johnson RA. Active myocarditis in the spectrum of acute dilated cardiomyopathies. Clinical features, histologic correlates, and clinical outcome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312:885–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504043121404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drory Y, Turetz Y, Hiss Y, Lev B, Fisman EZ, Pines A, Kramer MR. Sudden unexpected death in persons less than 40 years of age. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1991;68:1388–1392. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90251-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: Analysis of 1866 deaths in the united states, 1980–2006. Circulation. 2009;119:1085–1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman KL. Diagnosis of myocarditis: Death of dallas criteria. Circulation. 2006;113:593–595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.589663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman AM, McNamara D. Myocarditis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:1388–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowles NE, Richardson PJ, Olsen EG, Archard LC. Detection of coxsackie-b-virus-specific rna sequences in myocardial biopsy samples from patients with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1986;1:1120–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91837-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KS, Hufnagel G, Chapman NM, Tracy S. The group b coxsackieviruses and myocarditis. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2001;11:355–368. doi: 10.1002/rmv.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowlton KU. Cvb infection and mechanisms of viral cardiomyopathy. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2008;323:315–335. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandolf R, Canu A, Hofschneider PH. Coxsackie b3 virus can replicate in cultured human foetal heart cells and is inhibited by interferon. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1985;17:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asher DR, Cerny AM, Weiler SR, Horner JW, Keeler ML, Neptune MA, Jones SN, Bronson RT, Depinho RA, Finberg RW. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is essential for cardiomyocyte development. Genesis. 2005;42:77–85. doi: 10.1002/gene.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen CJ, Shieh JT, Pickles RJ, Okegawa T, Hsieh JT, Bergelson JM. The coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is a transmembrane component of the tight junction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:15191–15196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261452898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nalbantoglu J, Pari G, Karpati G, Holland PC. Expression of the primary coxsackie and adenovirus receptor is downregulated during skeletal muscle maturation and limits the efficacy of adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to muscle cells. Human Gene Therapy. 1999;10:1009–1019. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashimura T, Kodama M, Hotta Y, Hosoya J, Yoshida K, Ozawa T, Watanabe R, Okura Y, Kato K, Hanawa H, Kuwano R, Aizawa Y. Spatiotemporal changes of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor in rat hearts during postnatal development and in cultured cardiomyocytes of neonatal rat. Virchows Archiv. 2004;444:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fechner H, Noutsias M, Tschoepe C, Hinze K, Wang X, Escher F, Pauschinger M, Dekkers D, Vetter R, Paul M, Lamers J, Schultheiss HP, Poller W. Induction of coxsackievirus-adenovirus-receptor expression during myocardial tissue formation and remodeling: Identification of a cell-to-cell contact-dependent regulatory mechanism. Circulation. 2003;107:876–882. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050150.27478.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noutsias M, Fechner H, de Jonge H, Wang X, Dekkers D, Houtsmuller AB, Pauschinger M, Bergelson J, Warraich R, Yacoub M, Hetzer R, Lamers J, Schultheiss HP, Poller W. Human coxsackie-adenovirus receptor is colocalized with integrins alpha(v)beta(3) and alpha(v)beta(5) on the cardiomyocyte sarcolemma and upregulated in dilated cardiomyopathy: Implications for cardiotropic viral infections. Circulation. 2001;104:275–280. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitcheson JS, Hancox JC, Levi AJ. Cultured adult cardiac myocytes: Future applications, culture methods, morphological and electrophysiological properties. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;39:280–300. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lombardi R, Bell A, Senthil V, Sidhu J, Noseda M, Roberts R, Marian AJ. Differential interactions of thin filament proteins in two cardiac troponin t mouse models of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;79:109–117. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, Wu JC. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: Human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee A, Morosky SA, Delorme-Axford E, Dybdahl-Sissoko N, Oberste MS, Wang T, Coyne CB. The coxsackievirus b 3c protease cleaves mavs and trif to attenuate host type i interferon and apoptotic signaling. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7:e1001311. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carthy CM, Granville DJ, Watson KA, Anderson DR, Wilson JE, Yang D, Hunt DW, McManus BM. Caspase activation and specific cleavage of substrates after coxsackievirus b3-induced cytopathic effect in hela cells. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:7669–7675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7669-7675.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr Hl-1 cells: A cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotbart HA. Treatment of picornavirus infections. Antiviral Research. 2002;53:83–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, Han L, Sanchez-Freire V, Abilez OJ, Navarrete EG, Hu S, Wang L, Lee A, Pavlovic A, Lin S, Chen R, Hajjar RJ, Snyder MP, Dolmetsch RE, Butte MJ, Ashley EA, Longaker MT, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:130ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churko JM, Burridge PW, Wu JC. Generation of human ipscs from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells using non-integrative sendai virus in chemically defined conditions. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1036:81–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-511-8_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lian X, Hsiao C, Wilson G, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Azarin SM, Raval KK, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical wnt signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E1848–E1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Vusse GJ, van Bilsen M, Glatz JF. Cardiac fatty acid uptake and transport in health and disease. Cardiovascular Research. 2000;45:279–293. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanke KHW, van der Schaar HM, Belov GA, Feng Q, Duijsings D, Jackson CL, Ehrenfeld E, van Kuppeveld FJM. Gbf1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for arf, is crucial for coxsackievirus b3 rna replication. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:11940–11949. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorner AA, Wegmann F, Butz S, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Wolburg H, Mack A, Nasdala I, August B, Westermann J, Rathjen FG, Vestweber D. Coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (car) is essential for early embryonic cardiac development. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:3509–3521. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KS, Hufnagel G, Chapman NM, Tracy S. The group b coxsackieviruses and myocarditis. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2001;11:355–368. doi: 10.1002/rmv.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinkert S, Klingel K, Lindig V, Dorner A, Zeichhardt H, Spiller OB, Fechner H. Virus-host coevolution in a persistently coxsackievirus b3-infected cardiomyocyte cell line. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:13409–13419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00621-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scassa ME, Jaquenod de Giusti C, Questa M, Pretre G, Richardson GA, Bluguermann C, Romorini L, Ferrer MF, Sevlever GE, Miriuka SG, Gomez RM. Human embryonic stem cells and derived contractile embryoid bodies are susceptible to coxsakievirus b infection and respond to interferon ibeta treatment. Stem Cell Research. 2011;6:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhl U, Pauschinger M, Schwimmbeck PL, Seeberg B, Lober C, Noutsias M, Poller W, Schultheiss HP. Interferon-beta treatment eliminates cardiotropic viruses and improves left ventricular function in patients with myocardial persistence of viral genomes and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107:2793–2798. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072766.67150.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gale M, Jr, Katze MG. Molecular mechanisms of interferon resistance mediated by viral-directed inhibition of pkr, the interferon-induced protein kinase. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1998;78:29–46. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heim A, Grumbach I, Pring-Akerblom P, Stille-Siegener M, Muller G, Kandolf R, Figulla HR. Inhibition of coxsackievirus b3 carrier state infection of cultured human myocardial fibroblasts by ribavirin and human natural interferon-alpha. Antiviral Research. 1997;34:101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(97)01028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuo J, Quinn KK, Kye S, Cooper P, Damoiseaux R, Krogstad P. Fluoxetine is a potent inhibitor of coxsackievirus replication. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012;56:4838–4844. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00983-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Si X, McManus BM, Zhang J, Yuan J, Cheung C, Esfandiarei M, Suarez A, Morgan A, Luo H. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate reduces coxsackievirus b3 replication through inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:8014–8023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8014-8023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanke K, Krenn BM, Melchers WJ, Seipelt J, van Kuppeveld FJ. Pdtc inhibits picornavirus polyprotein processing and rna replication by transporting zinc ions into cells. The Journal of General Virology. 2007;88:1206–1217. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deonarain R, Cerullo D, Fuse K, Liu PP, Fish EN. Protective role for interferon-beta in coxsackievirus b3 infection. Circulation. 2004;110:3540–3543. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136824.73458.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundy SD, Zhu WZ, Regnier M, Laflamme MA. Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2013;22:1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saraste A, Arola A, Vuorinen T, Kyto V, Kallajoki M, Pulkki K, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Hyypia T. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis in experimental coxsackievirus b3 myocarditis. Cardiovascular Pathology : the Official Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 2003;12:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badorff C, Lee GH, Lamphear BJ, Martone ME, Campbell KP, Rhoads RE, Knowlton KU. Enteroviral protease 2a cleaves dystrophin: Evidence of cytoskeletal disruption in an acquired cardiomyopathy. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:320–326. doi: 10.1038/6543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham MW, Antone SM, Gulizia JM, McManus BM, Fischetti VA, Gauntt CJ. Cytotoxic and viral neutralizing antibodies crossreact with streptococcal m protein, enteroviruses, and human cardiac myosin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:1320–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kannankeril PJ, Roden DM. Drug-induced long qt and torsade de pointes: Recent advances. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2007;22:39–43. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32801129eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuel CE. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crotty S, Maag D, Arnold JJ, Zhong W, Lau JY, Hong Z, Andino R, Cameron CE. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an rna virus mutagen. Nature Medicine. 2000;6:1375–1379. doi: 10.1038/82191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graudins A, Vossler C, Wang R. Fluoxetine-induced cardiotoxicity with response to bicarbonate therapy. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1997;15:501–503. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.