Abstract

It has been known for many years that influenza viruses bind by their hemagglutinin surface glycoprotein to sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) on the surface of the host cell, and that avian viruses most commonly bind to sialic acid linked α2–3 to galactose while most human viruses bind to sialic acid in the α2–6 configuration. Over the past few years there has been a large increase in data on this binding due to technological advances in glycan binding assays, reverse genetic systems for influenza and in X-ray crystallography. The results show some surprising changes in binding specificity that do not appear to affect the ability of the virus to infect host cells.

Introduction

In the spring of 2013 there was an outbreak of a new human influenza virus, serotyped as H7N9, from scattered regions of China. The outbreak did not spread outside China, and disappeared within weeks as live bird markets were closed. However, new cases towards the end of 2013 and into 2014 show that the virus is still present. Like the previous outbreaks of avian influenza H5N1, H7N7 and H9N2 in humans, the H7N9 virus has not been shown to transmit from one human to another. There is ongoing concern that a few key mutations might confer the ability to spread in the human population. Much of the research activity to understand the factors that might lead to a human pandemic is directed to study of receptor binding and recent advances in technology have facilitated these efforts. This review summarizes the information available on receptor binding by influenza viruses using glycan arrays, structural investigation to understand the molecular basis of receptor specificity, together with studies on binding and cleavage of sialylated substrates by the neuraminidase, and compares the H7N9 data with recent information on seasonal human viruses, H3N2, H1N1 and influenza B.

Historical background

Influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family. These are enveloped viruses with a genome consisting of 8 segments of single-stranded, negative sense RNA, containing coding information for at least 11 functional proteins. Influenza type A and B viruses have two major surface glycoprotein antigens embedded in the viral membrane and forming the outer spikes of the virus particle. They are the hemagglutinin (HA, or H) that binds to sialic acid receptors and fuses the viral and cell membranes to release the viral nucleocapsids, and neuraminidase (NA, or N) which cleaves sialic acid. Neutralizing antibodies target these surface glycoproteins. Type A influenza viruses are divided into subtypes based on lack of cross-reactivity of the surface antigens, currently H1 to H16 and N1 to N9. Two groups of viral genome sequences from bats recently discovered have been tentatively designated H17N10 and H18N11. Live bat virus has not been recovered or propagated as yet, but it has been shown that H17 and H18 do not bind sialic acids and N10 and N11 do not cleave sialic acid and the receptors have not yet been identified [1].

The HA is the attachment protein, binding to sialylated glycans on the host cell surface, while the NA removes the sialic acid from glycans, thus acting as a receptor-destroying enzyme. The specificity of these two activities has become a subject of intense study. In the 1980s James Paulson and his colleagues showed that human influenza A viruses bind to sialylated glycans with an α2–6 linkage to galactose while avian influenza viruses bound to α2–3 linked sialic acid. They grew a human H3 isolate in the presence of horse serum that contains a potent inhibitor of human virus hemagglutination, α2 macroglobulin, and found a change in binding from Siaα2,6Gal to the Siaα2,3Gal linkage. This binding change was accompanied by a mutation in HA of Leu226Gln [2]. Furthermore, by applying selection using cycles of binding of an avian virus to red blood cells treated to display only Siaα2–6 glycans and amplification of bound virus, they isolated mutant viruses that bound only Siaα2–6 glycans. These viruses had the reciprocal single amino acid substitution in the HA of Gln226Leu while passaged in MDCK cells but rapidly reverted to 226Q when grown in eggs [3]. Studies on host specificity of influenza viruses, and in particular on what changes are needed to allow an avian virus to infect and transmit among humans have focused on this finding ever since [4,5]. A molecular explanation for the dramatic difference in binding Siaα2–3 versus α2–6 was found in crystal structures of avian and human HAs bound to sialylated pentasaccharides LSTa or LSTc. The sialic acids are bound identically but the rest of the glycan in Siaα2–3 follows an extended conformation while the glycan in Siaα2–6 bends back on itself, as seen in a recent study of HA of H7N9 viruses in complex with LSTa and LSTc [6].

If NA is truly a receptor-destroying enzyme its specificity should match that of the HA. Trends have been noted in NA specificity that have been interpreted as NA mutations to match HA to humans, but the changes are minor decreases in the ratio of 2–3/2–6 activity and in no case has the influenza NA been found to prefer Siaα2–6 over Siaα2–3 (reviewed in [7]).

Glycan Array analysis

The development of glycan arrays in the early 2000’s has revolutionized the study of influenza virus binding specificity. Until then only a few sialylated glycans were available for binding studies, such as sialyllactose, the milk pentasaccharides LSTa and LSTc, and gangliosides [8]. The establishment and funding of the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) led to development of new chemo-enzymatic methods for glycan synthesis that allowed the printing of several hundred individual glycans on a glass slide [9,10]. The current version of the CFG Glycan Array has 610 glycans, of which 166 are sialylated. Other array platforms have been developed including use of neo-glycolipids [11] and glycans attached to bovine serum albumin [12]. Raw data from the CFG arrays are publicly available, posted on the CFG web site http://www.functionalglycomics.org/glycomics/publicdata/. It is instructive to examine the raw data in addition to the processed and interpreted accounts that are published in journals, where a large amount of information is necessarily lost.

Several studies have been made of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 viruses using various glycan array platforms. At first sight the results are conflicting but the conflicts appear to be from analysis of only a single concentration of virus or recombinant HA along with differing interpretation of the significance of minor binding signals [13]. The conclusion is that pdmH1N1 viruses show preferential binding to α2–6 sialylated glycans with lesser but maybe significant binding to α2–3 sialylated glycans.

We undertook glycan array screening of a comprehensive collection of human H3N2 viruses isolated from 1968 to 2012 and found surprising variation in binding specificities. The study was done using viruses passaged only in mammalian cell lines to avoid changes due to adaptation for growth in embryonated chicken eggs as for vaccine production. H3N2 viruses first appeared in humans in 1968 and isolates from the early years preferentially bind short, branched α2–6 sialylated glycans. In later years the preference changed to long, linear α2–6 sialylated polylactosamine structures (Figure 1). However, there are exceptions to this pattern (Figure 2), including viruses that bind α2–3 sialic acids, preferentially or exclusively, and viruses that bind only a very restricted set of glycans [14]. While we recognize that the glycan array does not contain all the sialylated structures of a mammalian cell, and the single spot of each glycan cannot be a true reflection of the cell surface, there is no doubt that the binding site changes with antigenic changes to give differences in avidity and specificity without noticeable decrease in viral fitness or transmissivity. All of the viruses we studied spread around the world.

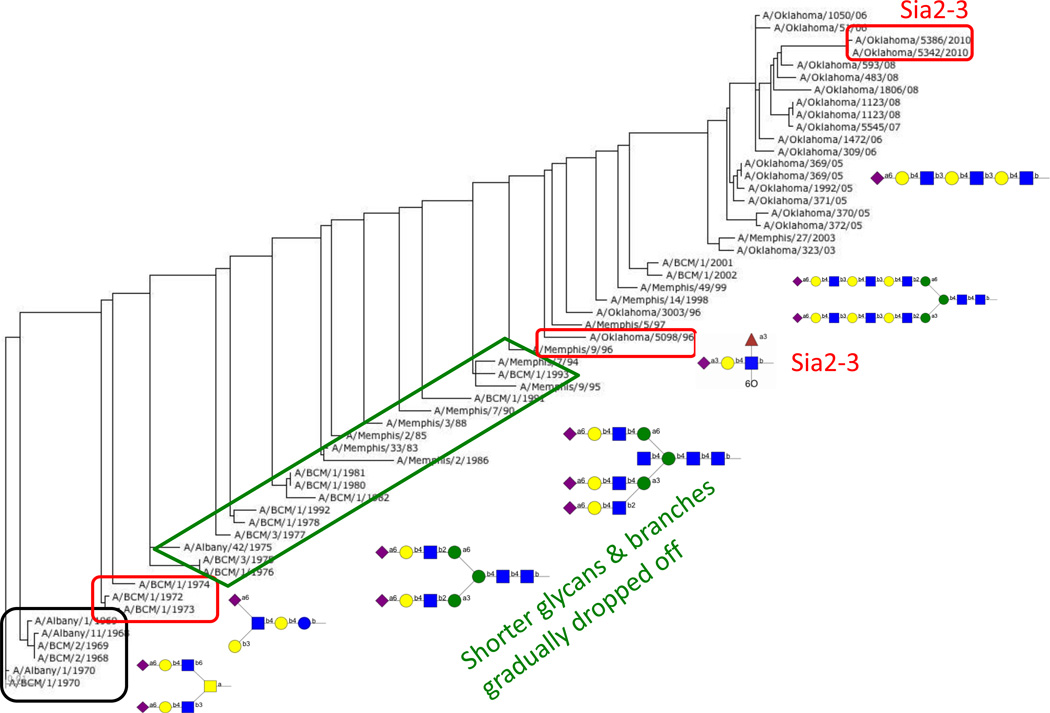

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic of how binding by human H3N2 viruses has changed over the years. The figure shows the phylogenetic tree of HA based on amino acid sequence from 1968 (bottom left) to 2012 (top right) with sample structures of glycans that are bound. Binding data is from the CFG Glycan Array v5.1 [14] and the tree was generated at https://flu.lanl.gov/ [28].

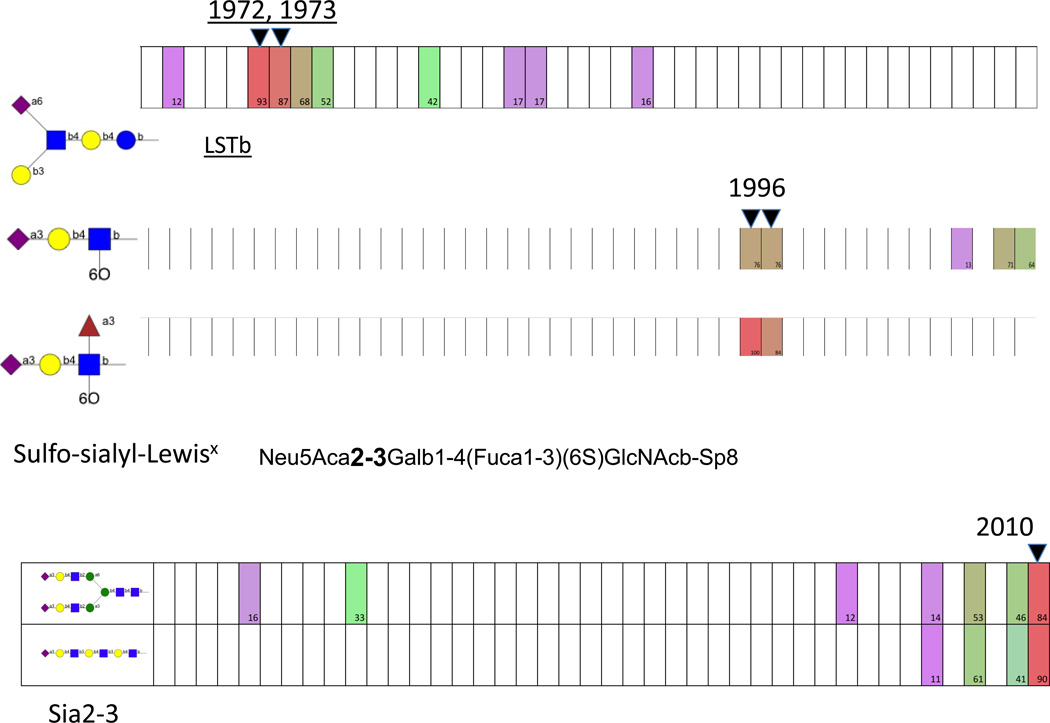

Figure 2.

Examples of binding by human H3N2 isolates that diverge from the pattern shown in Figure 1. The boxes represent each virus from 1968 (left) to 2010 (right). Binding is color coded as percent of the highest signal, from 100% (red) through 50% (green) to 10% (violet) with white representing <10%. These are the highest-binding glycans for the strains in years indicated. Data from Gulati et al. [14].

The idea that receptor specificity determines host tropism has been vigorously explored. Most studies aiming to alter host specificity have been done with H5N1 viruses. This subtype, previously only seen in birds, was first recognized as a new human pathogen in 1997 and became more prevalent in the early 2000s, but did not transmit from one human to another except in very rare instances. There was considerable concern that, as in the early Paulson experiments, a single mutation might confer on this virus the ability to transmit between humans and so start a new pandemic to which the human population had no immunity. This turned out not to be the case, and multiple mutations were required for an H5N1 virus to transmit between ferrets [4,5]. Very stringent biosecurity was applied to these experiments and there is no knowledge of whether such combinations of mutants, not seen in nature, would enable human-to-human transmission. These mutant viruses have increased affinity for α2–6 linked sialic acids but although a relationship between the sialic acid linkage and infectivity or transmission is inferred, we do not yet know if it is direct.

The same concerns arose over the H7N9 viruses. To the end of February 2014 WHO has reported a total of 375 laboratory-confirmed cases of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, including 115 deaths. The vast majority of cases have occurred in China or the Hong Kong SAR, with two in Taipei and one in Malaysia in a traveller from China. Most cases appear to be due to direct transmission from infected poultry. There may have been rare, limited human-to-human infection but to date there have been no sustained human transmissions (http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/en/).

The H7N9 virus HAs bind α2–3 linked sialic acids but some of the 2013 H7 HAs have Leu at 226 and it was thought that this might confer the ability to bind α2–6 receptors. Recombinant HA binds only Siaα2–3 glycans, and only a small subset of them. These are generally short, typical N- or O-linked glycans, and some are sulfated [6]. Two human H7N9 viruses with 226 Q or L showed similar binding properties and a similar capacity to replicate in ex vivo human lung tissues. Both could be transmitted between ferrets by direct contact but not by aerosol [15]. When an H7N1 virus was serially passaged in ferrets, the resulting virus was able to transmit to either co-housed or airborne contact ferrets but there was no change in the sequence around the HA receptor binding site and so presumably no change in binding specificity [16].

The arrays generate a large amount of data but the relationship between binding specificity and host restriction is very unclear. Animal models for human influenza are imperfect; mice can be infected by mouse-adapted influenza viruses but do not develop a disease that mimics the human influenza. Ferrets are the preferred model because they show similar symptoms as humans, but to date the relationship to the human disease is not clear given the complexity of potential receptors.

Binding by neuraminidase

When glycan array screens were run on H3N2 human influenza viruses the surprising finding was that some viruses bind to Siaα2–3 glycans, in some cases better than to the canonical human receptors. For the 2010–2012 isolates, the α2–3 binding was found to be mediated by the neuraminidase. Lin et al showed that this binding was due to a mutation in the NA active site resulting in increased substrate binding [17]. This initial study found that the NA is just as active as wildtype, but this anomaly was reversed in a later study where a classical enzyme kinetics study showed the recombinant mutant NA had activity reduced by 2 orders of magnitude [18]. The reason for the discrepancy may be that the virus population contained a mixture of wild type and mutant sequences. We and others have been unable to clone a population with 100% mutation, presumably because some NA activity is required for virus propagation [14,17]. Hooper and Bloom recently isolated a virus from a reverse genetics experiment using an HA gene mutated to abrogate receptor binding [19]. The rescued virus had an N1 NA mutation of G147R and they showed that this NA could agglutinate red blood cells in an oseltamivir-sensitive manner, suggesting that a ligand bound in the NA active site allowed the virus to infect cells in the absence of HA binding activity. Viruses that infect cells using their NA as the receptor-binding protein would be resistant to antibodies induced by vaccines that contain only HA.

Earlier studies also showed binding of red blood cells by NAs of several avian influenza viruses, but the mechanism is different, involving a second sialic acid binding site distinct from the active site, as shown by mutagenesis and crystal structures of N9 and N6 NA bound to two sialic acid molecules per subunit (reviewed in [7]). The NA of recent H7N9 viruses also binds red blood cells. To date no biological function of this second binding site has been demonstrated. Uhlendorf et al [20] suggested the second site might assist catalysis by holding substrate ready for catalysis, but the different specificities of the cleavage and binding [21] make this less likely.

Structural understanding

The early crystal structures of HA complexed with sialylated trisaccharides were at low resolution and often the distal sugars were not visible. The commercially available pentasaccharide milk sugars called LSTa (Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNacβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) and LSTc (Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNacβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) proved to form more stable complexes and showed that when bound to HA, usually avian, the LSTa is in an extended conformation while LSTc bound to human influenza HA is folded back on itself due to interactions between the sialic acid and the N-acetyl glucosamine at position 3. Thus, although the sialic acid binds in the same way, the tracks and therefore interactions of the rest of the glycan chain are very different. Crystal structures of sialylated oligosaccharides complexed with recombinant HA have recently been obtained at higher resolution and show some unexpected interactions due to plasticity of the glycan conformation. These structures explain why the H7 HA with Leu226 does not bind human receptors as was predicted from the sequence but found not to be the case in binding studies [6].

In human H1N1 HA from 1918 and 2009 the mutation D225G confers dual specificity instead of the predicted nearly exclusive Siaα2–6 binding. From crystal structures of HA complexes, the explanation is that D225 forms a salt bridge with K222. When there is G at 225 the released K222 moves away to allow Q226 to interact with the avian receptor [22]. In general, these studies emphasize the importance of obtaining crystal structures rather than relying on homology modeling in understanding receptor specificity.

What are the real receptors? Studies of the respiratory tract glycome

The remarkable advances in being able to analyze binding of hundreds of glycans in the glycan array and obtaining crystal structures of HA-glycan complexes still leaves a big question of what receptors are used in vivo. Early studies staining respiratory tract tissues with sialic acid-specific lectins gave some clues, suggesting that since α2–3 sialic acids are only present deep in human lungs, this distribution might explain why avian viruses can cause severe pneumonia in the rare cases where they penetrate so deeply. However, the lectin studies are not quantitative and tend to give an all-or-nothing result. Mass spectrometry has been used to try to unravel the respiratory glycome. The complexity of sugar structures and linkages mean that much data is ambiguous, and the analyses have to be done using whole tissue rather than just the respiratory epithelial cells, but a certain amount of information does emerge. Aich et al showed that glycans on chicken red cells are short branched structures and lack long linear polylactosamine chains [23]. This fits well with the glycan array binding patterns of H3N2 viruses isolated in the mid-1990s. These viruses lost ability to bind chicken red cells and they predominantly bind long linear polylactosamine structures [14]. Walther et al studied the glycome of human respiratory tract tissues. They found that a large number of glycans that are present in the human respiratory tract are missing from even the largest arrays, and that the array binding is not predictive of infectivity [24]. There are likely two reasons: one is that binding does not necessarily lead to productive infection and the other that the arrays need to be targeted to the organs being studied. Two recent papers have investigated the relationship between the glycome of swine respiratory tissues and influenza virus infection [25,26].

Remaining questions

The overarching questions still to be answered are what receptors are used in the human respiratory tract and how much the receptor binding specificity contributes to human-to-human transmission. Lectin staining has shown a preponderance of 2–6 sialylated glycans in the upper respiratory tract and 2–3 in the lungs, giving rise to the idea that avian viruses cause pneumonia because they replicate in alveolar sites. However, much more sensitive methods are needed to determine if there is a direct relationship between binding and disease. Influenza viruses bind to many cell types but there are additional restrictions that limit productive infection (defined as production of infectious progeny viruses) that are not yet characterized [27].

Highlights.

It has been known since the 1950s that influenza virus uses sialic acid as a receptor

Development of glycan arrays has allowed an unprecedented analysis of the fine specificity of binding

While the general rule is that avian viruses bind to sialic acids bound α2–3 to galactose while human viruses bind α2–6 linked sialic acid, avian viruses can infect people without a change in specificity

The role of receptor specificity in transmission of influenza viruses is still unclear

Acknowledgements

Work in the author’s laboratory was supported by NIH grant R01AI50933 and by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (grants U54GM62116, PI James Paulson and HHSN272201400006C, PI Richard Cummings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Wu Y, Tefsen B, Shi Y, Gao GF. Bat-derived influenza-like viruses H17N10 and H18N11. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers GN, Paulson JC, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature. 1983;304:76–78. doi: 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers GN, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Wang XF, Higa HH, Paulson JC. Host-mediated selection of influenza virus receptor variants. Sialic acid-alpha 2,6Gal-specific clones of A/duck/Ukraine/1/63 revert to sialic acid-alpha 2,3Gal-specific wild type in ovo. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7362–7367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, et al. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. Together with reference 5, this paper describes passaging a mutated H5N1 virus multiple times in ferrets until it acquired the ability to transmit between ferrets by aerosol.

- 5. Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. Together with reference 4, this paper describes passaging a mutated H5N1 virus multiple times in ferrets until it acquired the ability to transmit between ferrets by aerosol.

- 6.Xu R, de Vries RP, Zhu X, Nycholat CM, McBride R, Yu W, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. Preferential recognition of avian-like receptors in human influenza A H7N9 viruses. Science. 2013;342:1230–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1243761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Air GM. Influenza neuraminidase. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012;6:245–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki T, Portner A, Scroggs RA, Uchikawa M, Koyama N, Matsuo K, Suzuki Y, Takimoto T. Receptor specificities of human respiroviruses. J Virol. 2001;75:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4604-4613.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blixt O, Head S, Mondala T, Scanlan C, Huflejt ME, Alvarez R, Bryan MC, Fazio F, Calarese D, Stevens J, et al. Printed covalent glycan array for ligand profiling of diverse glycan binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17033–17038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song X, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Glycan microarrays. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;800:163–171. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-349-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palma AS, Feizi T, Childs RA, Chai W, Liu Y. The neoglycolipid (NGL)-based oligosaccharide microarray system poised to decipher the meta-glycome. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;18:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muthana SM, Gildersleeve JC. Glycan microarrays: powerful tools for biomarker discovery. Cancer Biomark. 2014;14:29–41. doi: 10.3233/CBM-130383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulati S, Lasanajak Y, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Air GM. Glycan array analysis of influenza H1N1 binding and release. Cancer Biomark. 2014;14:43–53. doi: 10.3233/CBM-130376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gulati S, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Couch RB, Griesemer SB, St George K, Webster RG, Air GM. Human H3N2 Influenza Viruses Isolated from 1968 To 2012 Show Varying Preference for Receptor Substructures with No Apparent Consequences for Disease or Spread. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066325. Glycan Array analysis showed mutations in human H3N2 viruses driven by antigenic drift are accompanied by an evolution of their HA ligand specificity.

- 15.Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature. 2013;501:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sutton TC, Finch C, Shao H, Angel M, Chen H, Capua I, Cattoli G, Monne I, Perez DR. Airborne Transmission of Highly Pathogenic H7N1 Influenza in Ferrets. J Virol. 2014 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02765-13. In contrast to the generally accepted idea that transmission between mammals is dependent on changing binding specificity from avian to mammalian character, multiple passages of an H7 virus in ferrets led to a transmissible virus that had no change in the HA receptor binding site.

- 17.Lin YP, Gregory V, Collins P, Kloess J, Wharton S, Cattle N, Lackenby A, Daniels R, Hay A. Neuraminidase receptor binding variants of human influenza A(H3N2) viruses resulting from substitution of aspartic acid 151 in the catalytic site: a role in virus attachment? J Virol. 2010;84:6769–6781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00458-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu X, McBride R, Nycholat CM, Yu W, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. Influenza virus neuraminidases with reduced enzymatic activity that avidly bind sialic Acid receptors. J Virol. 2012;86:13371–13383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01426-12. Crystal structure and enzymatic analysis showed that neuraminidase with a mutation in the active site can bind substrate but not cleave it, thus acting as a binding protein.

- 19. Hooper KA, Bloom JD. A mutant influenza virus that uses an N1 neuraminidase as the receptor-binding protein. J Virol. 2013;87:12531–12540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01889-13. A spontaneous mutation G147R allowed N1 neuraminidase to coopt the function of HA and allow efficient productive infection by a virus in which the HA carried mutations that abolished its binding function.

- 20.Uhlendorff J, Matrosovich T, Klenk HD, Matrosovich M. Functional significance of the hemadsorption activity of influenza virus neuraminidase and its alteration in pandemic viruses. Arch Virol. 2009;154:945–957. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Air GM, Laver WG. Red cells bound to influenza virus N9 neuraminidase are not released by the N9 neuraminidase activity. Virology. 1995;211:278–284. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Shi Y, Qi J, Gao F, Li Q, Fan Z, Yan J, Gao GF. Molecular basis of the receptor binding specificity switch of the hemagglutinins from both the 1918 and 2009 pandemic influenza A viruses by a D225G substitution. J Virol. 2013;87:5949–5958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00545-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aich U, Beckley N, Shriver Z, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Hobbie S, Sasisekharan R. Glycomics-based analysis of chicken red blood cells provides insight into the selectivity of the viral agglutination assay. The FEBS journal. 2011;278:1699–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walther T, Karamanska R, Chan RW, Chan MC, Jia N, Air G, Hopton C, Wong MP, Dell A, Malik Peiris JS, et al. Glycomic analysis of human respiratory tract tissues and correlation with influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003223. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003223. A comprehensive mass spectrometric analysis of the glycans present in the human lung and bronchus with some data for nasopharynx. Many more glycan structures were found than are represented on current glycan arrays, emphasizing the need for tissue-specific glycan arrays.

- 25.Byrd-Leotis L, Liu R, Bradley KC, Lasanajak Y, Cummings SF, Song X, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Galloway SE, Culhane MR, Smith DF, et al. Shotgun glycomics of pig lung identifies natural endogenous receptors for influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323162111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan RW, Karamanska R, Van Poucke S, Van Reeth K, Chan IW, Chan MC, Dell A, Peiris JS, Haslam SM, Guan Y, et al. Infection of swine ex vivo tissues with avian viruses including H7N9 and correlation with glycomic analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:1269–1282. doi: 10.1111/irv.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulati S, Smith DF, Air GM. Deletions of neuraminidase and resistance to oseltamivir may be a consequence of restricted receptor specificity in recent H3N2 influenza viruses. Virol J. 2009;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]