Abstract

The ability to use chemical reactivity to monitor and control biomolecular processes with a spatial and temporal precision motivated the development of light-triggered in vivo chemistries. To this end, the photoinduced tetrazole-alkene cycloaddition, also termed “photoclick chemistry” offers a very rapid chemical ligation platform for the manipulation of biomolecules and matrices in vivo. Here we outline the recent developments in the optimization of this chemistry, ranging from the search for substrates that offer two-photon photoactivatability, superior reaction kinetics, and/or genetic encodability, to the study of the reaction mechanism. The applications of the photoclick chemistry in protein labeling in vitro and in vivo as well as in preparing “smart” hydrogels for 3D cell culture are highlighted.

Introduction

Bioorthogonal reaction tools continue to advance rapidly over the last few years owing to the unabated desire to study biological processes in their native environment [1]. One such tool is the photoinduced click reactions that hold a great promise to bring the spatial and temporal precision associated with light to the study of biomolecular systems in living systems [2]. Inspired by the seminal work of Rolf Huisgen on the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of the diphenyltetrazole as a photoactivatable 1,3-dipole precursor [3], we reported in 2008 that the high reactivity of the diphenyltetrazole can be harnessed for protein labeling both in aqueous medium [4••] and inside bacterial cells [5••], owing to the fact that the pyrazoline cycloadducts are fluorescent. We termed this tetrazole-alkene cycloaddition reaction “photoclick chemistry” because of the necessity of photon in initiating the reaction and the satisfaction of the criteria for a “spring-loaded” click reaction proposed by Sharpless [6]. Since these early work, many aspects of the photoclick chemistry has been examined and optimized [7], and its utility in biological systems continue to expand. In this article, we will review the recent technological advances of this bioorthogonal reaction and its applications in site-specific protein labeling in vitro and in living cells as well as in preparing “smart” hydrogels for 3D cell culture and controlled release of proteins in vivo.

Compared to other bioorthogonal reactions, the photoclick chemistry offers several unique advantages. First, the reaction proceeds readily with a shine of light without the use of potentially toxic metal catalysts and ligands, offering a high level of spatiotemporal control. Second, the tetrazole to nitrile imine conversion can be triggered with a low-power UV lamp, LED light, or laser beam because of the high quantum efficiency of the photoinduced tetrazole ring rupture. Third, the reaction is fluorogenic with a tunable emission, allowing direct monitoring of reaction progress in vivo. Finally, because of the small size of the alkene substrates, photoclick chemistry can be readily integrated into the biological systems, facilitating the adoption of this reactivity-based tool in various biological systems.

Tuning photoactivation wavelength

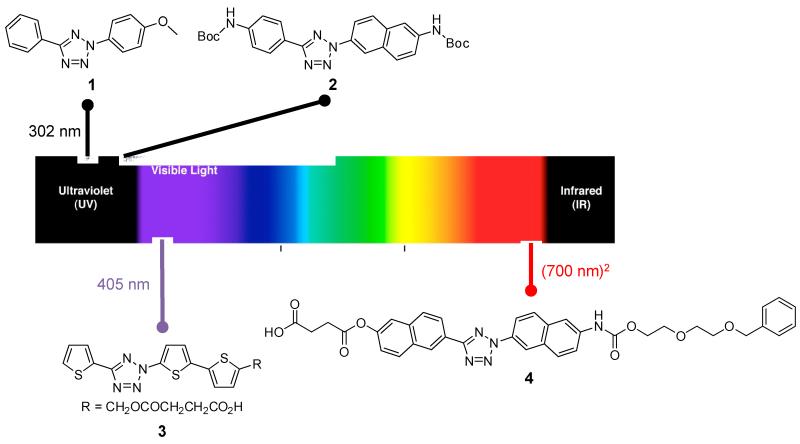

The initial photoclick chemistry was performed with a handheld UV lamp with irradiation band centered at 302 nm or 365 nm. UV light in these regions may pose considerable phototoxicity to living cells [8]. In addition, microscopes are not typically equipped with UV lasers, preventing the wider use of photoclick chemistry in biological systems. To overcome these limitations, a 405 nm laser-activatable terthiophene-tetrazole was designed (structure 3 in Figure 1) [9]. The oligothiophene was used because it readily accommodates the isosteric tetrazole ring in its chain without disruption of the extended π conjugation system. The quantum yield of the terthiophene-tetrazole ring rupture was measured to be 0.16, significantly higher than those of diphenyltetrazoles (ΦT = 0.006-0.04) [10,11]. Because of its high HOMO energy [12], the terthiophene-tetrazole 3 exhibited fast reaction kinetics toward a fumarate-derived dipolarophile in 1:1 PBS/acetonitrile mixed solvent (k2 = 1299 ± 110 M−1 s−1). This 405 nm laser-activatable terthiophene-tetrazole was used to fluorescently label the fumarate-docetaxel-bound microtubules in live CHO cells in a spatiotemporally controlled manner [9]. Furthermore, the bithiophene-tetazoles carrying the styrenyl or phenylbutadienyl substituent at the C5-position produced the pyrazoline adducts with the emissions in the red or near-infrared region, which should minimize the interference caused by autofluorescence in biological tissues [13].

Figure 1.

Design of tetrazoles with variable photoactivation wavelengths.

To reduce light scattering in turbid biological tissues and improve three dimensional localization of the excitation, a femtosecond 700 nm near infrared (NIR) laser light was investigated as a biocompatible light source for triggering the photoclick chemistry in living cells [14•]. It was found that the naphthalene-tetrazoles (e.g., structure 4 in Figure 1) showed strong two-photon absorption when excited with a 700 nm femtosecond pulsed laser, with the two-photon absorption cross section, δaT, of 12 GM (= 10−50 cm4s/photon). This naphthalene-tetrazole also showed high ring-rupture quantum yield (ΦT = 0.33). Importantly, the effective two-photon cycloaddition reaction cross section was measured to be 3.8 GM, superior to the uncaging efficiency of the widely used two-photon protecting group 6-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin-4-ylmethyl acetate (BHC-OAc, δur = 0.95 GM) under similar conditions [15]. This naphthalene-tetrazole allowed the site-specific modification of an acrylamide-encoded superfolder GFP in PBS buffer via the two-photon triggered photoclick chemistry. Moreover, the application of this two-photon photoclick chemistry to the CHO cells pre-treated with a fumarate-modified docetaxel resulted in fluorescent labeling of microtubules with higher signal-to-noise ratios than the 405 nm laser-triggered reaction [9].

Uncovering reaction mechanism

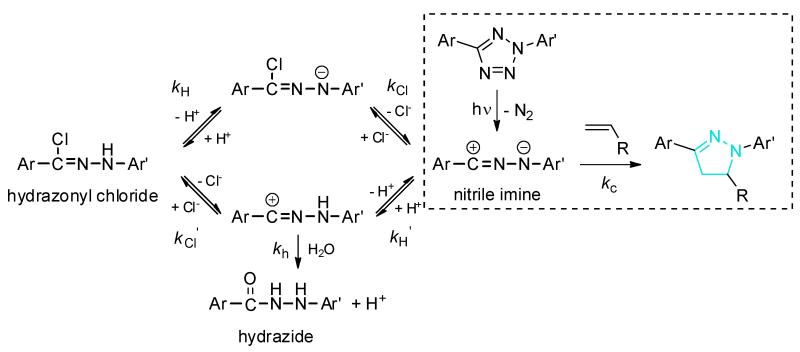

In the original report of the photoclick chemistry [4••], a two-step mechanism was proposed in which a rapid photoinduced, irreversible cycloreversion reaction to generate the nitrile imine intermediate was followed by a slower rate-determining 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction with the alkene dipolarophile (box in dashed line in Figure 2). A key observation supporting this mechanism is the formation of a transient intermediate with strong absorption at 370 nm that was assigned to the nitrile imine. Later, Carell and co-workers [16•] cleverly showed that the hydrazonyl chloride could serve as an alternative precursor for the reactive nitrile imine, leading to a light-independent nitrile imine-alkene cycloaddition in aqueous buffer. This realization prompted Liu and co-workers to conduct a comprehensive study of the effect of pH and chloride on the rate of nitrile imine-alkene cycloaddition in aqueous buffer [17•]. They found that the cycloaddition reaction is most favorable when it is conducted in basic pH and in the absence of chloride (Figure 2). The apparent cycloaddition rate, kapp, has an inverse linear dependence on chloride concentration, indicating that chloride inhibits the cycloaddition reaction. When the cycloaddition was carried out between the hydrazonyl chloride and an acrylamide-encoded sfGFP at pH 7.0 in the presence of 200 mM Cl−, the product became almost undetectable. Thus, they proposed a mechanism (Figure 2) in which the hydrazonyl chloride and the nitrile imine exist in a fast equilibrium and the observed cycloaddition rate is calculated based on the following equation: [17]. Indeed, the intrinsic rate constant, kc, for the cycloaddition between the hydrazonyl chloride and the acrylamide-encoded sfGFP was estimated to be ≥34 000 M−1 s−1, comparable to that of a genetically encoded tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene ligation [18].

Figure 2.

An expanded mechanistic view of the photoclick chemistry in PBS buffer.

With the insights gleaned from the hydrazonyl chloride-mediated cycloaddition studies, the transient intermediate generated after tetrazole ring rupture in 1:1 acetonitrile/PBS buffer ([Cl−] = 140 mM) is most likely the hydrazonyl chloride, which serves as a reservoir for and in rapid equilibrium with the more reactive nitrile imine in (Figure 2). In supporting this expanded view, we found recently [19•] that the tetrazole underwent significantly faster cycloaddition reaction with a strained cyclopropene derivative in phosphate buffer without chloride (vide infra); indeed, a rate constant as high as 34 000 ± 1 300 M−1 s−1 was obtained in a fluorescence-based measurement, which places the photoclick chemistry among the fastest bioorthogonal reactions known today [20].

Site-Specific Protein Labeling

An important application of bioorthogonal reactions is to label proteins in their native environment [21]. To this end, a two-step procedure is employed: a bioorthogonal tag is first introduced into the protein of interest site-specifically using amber codon suppression technique [22]; and then a biophysical probe carrying the cognate functionality is allowed to react selectively with the pre-tagged protein via the corresponding bioorthogonal reaction. For the application of photoclick chemistry to protein labeling, one can either genetically encode a tetrazole moiety [23] or an alkene dipolarophile. Although p-(2-tetrazole)phenylalanine has been incorporated site-selectively into the proteins [24] using an engineered M. jannaschii tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase/MjtRNACUA pair, the photoclick reaction with a fumarate-modified fluorescein was slow (k2 = 0.082 ± 0.011 M−1 s−1 in 1:1 ACN/PBS) because of the reduced reactivity of the monoaryltetrazole. Reciprocally, O-allyltyrosine (structure 5 in Figure 3a) offered the first genetically encoded alkene reporter for the photoclick chemistry-mediated protein labeling in bacteria [5••], even though the reaction was still very slow (k2 = 0.00202 ± 0.00007 M−1 s−1 in 1:1 ACN/PBS).

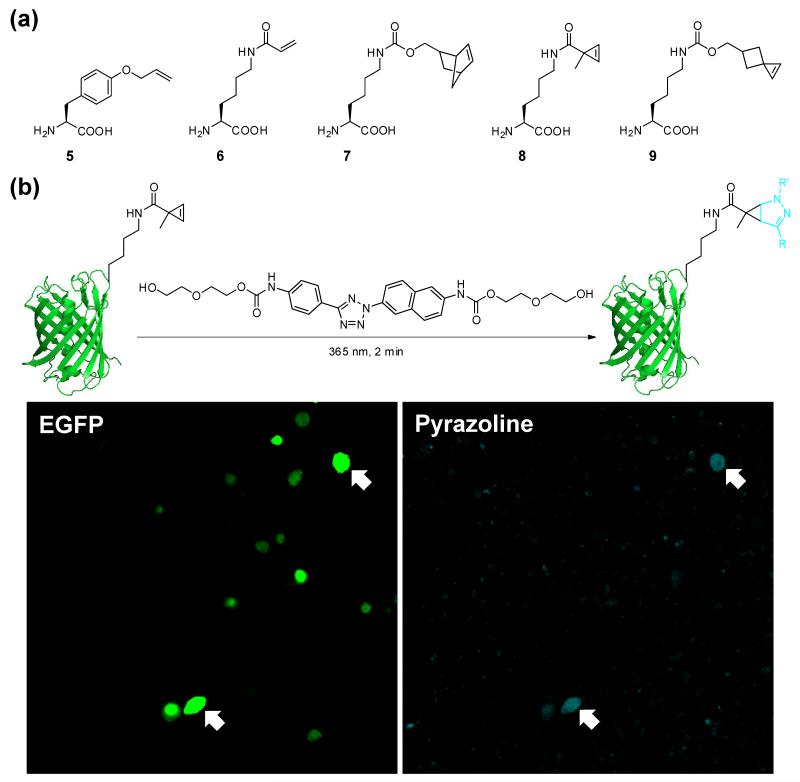

Figure 3.

(a) Genetically encodable alkene amino acids for the photoclick chemistry. (b) Protein labeling inside mammalian cells by the photoclick chemistry.

Two strategies have been successfully developed to increase the reactivity of the alkene reporters. In one approach, Liu and co-workers reported the genetic encoding of the electron-deficient acrylamide functionality appended to the lysine side chain (AcrK, structure 6 in Figure 3a) for site-specific protein modification via the nitrile imine-alkene cycloaddition [25]. The appeal of acrylamide as a bioorthogonal reporter stems from its relatively small size and its stability in biological milieu. The utility of AcrK was demonstrated through fluorescent labeling of the membrane protein OmpX on E. coli cell surface. In a separate study, Wang and co-workers evolved an orthogonal tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pair that allows selective incorporation of AcrK into the N-terminus of bacterial tubulin-like cytoskeleton protein FtsZ. The AcrK-encoded FtsZ protein was then fluorescently labeled in E. coli cells using photoclick chemistry. In addition, AcrK was successfully incorporated into the GFP-TAG-mCherry-HA protein in Arabidopsis thaliana, a widely used plant model [26].

In another approach, the strain effect was exploited [1]. Earlier on, it was observed that the strained alkene norbornene exhibited robust reactivity in the photoclick reaction with the macrocyclic tetrazole [27]. Later, Carell and co-workers [16•] reported the site-specific incorporation of a norbornene-modified lysine (structure 7 in Figure 3a), which was then used to direct both the hydrazonyl chloride and the tetrazole-mediated cycloaddition reactions. It is noteworthy that norbornene also serves as a privileged substrate for the in vivo tetrazine ligation in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells [28,29] as well as in animals [30]. In parallel, we reported the genetic encoding of a cyclopropene-modified lysine (CpK, structure 8 in Figure 3a) because of its small size and high reactivity [31•]. Kinetic study of the reaction of tetrazole 1 with the 3,3-disubstituted cyclopropene revealed a k2 value of 58 ± 16 M−1 s−1 in 1:1 acetonitrile/PBS, roughly twice as fast as with norbornene under the same condition. The utility of cyclopropene to direct site-specific modification of green fluorescent protein inside HEK293T cells was subsequently demonstrated (Figure 3b). Notably, cyclopropene has also been exploited in tetrazine ligation by Prescher and co-workers for visualizing cell surface glycans [32] and by Devaraj and co-workers for imaging phospholipids in SKBR3 cells [33]. Recently, Prescher and co-workers showed that the isomeric cyclopropenes could serve as exclusive substrates for either photoclick chemistry or tetrazine ligation depending on their substitution patterns [34].

The 3,3-substituents lie in close proximity to the cyclopropene π-bond, thereby causing steric hindrance to the incoming nitrile imine along the reaction coordinate. In an effort to reduce this steric hindrance, a spiro[2.3]hex-1-ene was synthesized that showed excellent stability in biological systems and extraordinary reactivity in the photoclick chemistry [19•]. In a NMR-based competition study, spiro[2.3]hex-1-ene was found to be about 17 times more reactive than the 3,3-disubstituted cyclopropene. In chloride-free phosphate buffer/acetonitrile mixed solvent (1:1), spiro[2.3]hex-1-ene reacted with a water-soluble tetrazole at a very fast rate with k2 value of 34 000 ± 1 300 M−1 s−1. In addition, a spiro[2.3]hex-1-ene-derived lysine (SphK, structure 9 in Figure 3a) was genetically encoded into sfGFP through the wild-type MmPylRS/tRNACUA pair, enabling fast protein modification by a water-soluble tetrazole in chloride-free phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (k2 = 10 420 ± 810 M−1 s−1) [19]. The availability of this robust, genetically encodable strained alkene offers some exciting opportunities for in vivo applications of the photoclick chemistry.

In situ hydrogel formation/disassembly

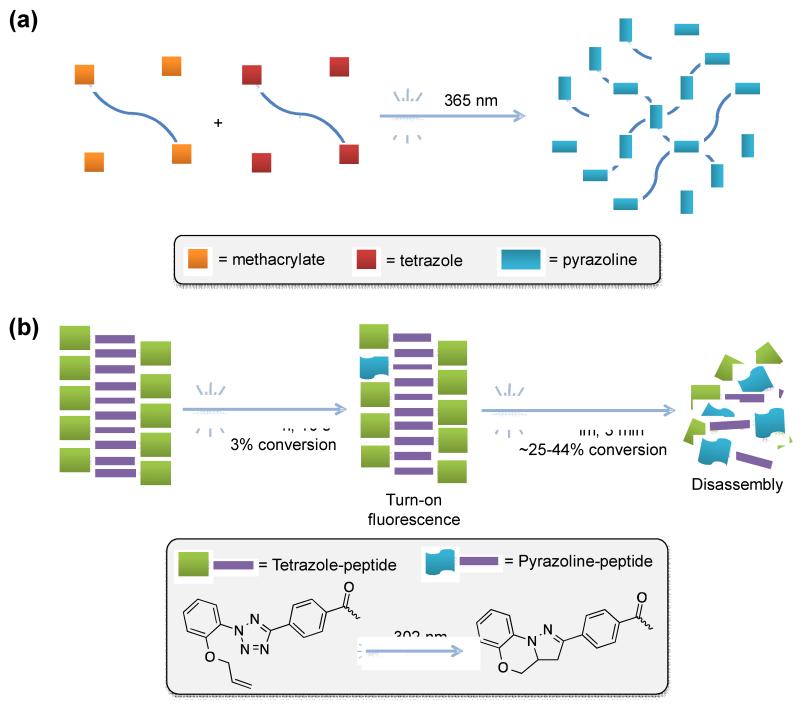

Bioorthogonal click reactions have been increasingly employed in the in situ formation of hydrogels owing to their fast reaction kinetics and specificity [35]. Zhong and co-workers reported the use of the photoclick chemistry as a novel strategy to fabricate hydrogels in situ for facile encapsulation and sustained release of proteins (Figure 4a) [36]. The cytocompatibility of the hydrogel formed was tested in L929 fibroblast showing no apparent cytotoxicity, suggesting its potential utility in making 3D cell culture matrix. The hydrogels showed the sustained and quantitative release of proteins while retaining their bioactivity. The fluorescent “turn-on” also allowed them to monitor the hydrogel formation and its fate in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 4.

Supramolecular hydrogel formation via the photoclick chemistry.

An important goal in cell biology is to control cell growth with a high spatial and temporal resolution. Hydrogels mimic the extracellular matrix where cells are imbedded in tissues. Furthermore, hydrogel systems that recapitulate extracellular matrix dynamics can benefit from the incorporation of the photoresponsive moieties that photomodulate cellular microenvironment [37•]. To this end, Zhang and co-workers capitalized the intramolecular photoclick chemistry [38] in their design of “smart” hydrogels for 3D cell encapsulation and release (Figure 4b) [39]. The hydrogels were assembled from the tetrazole-modified short peptides, which underwent rapid photoinduced disassembly upon exposure to UV light. The formation of the tilted tricyclic pyrazoline structure disrupted regular π-π stacking of the tetrazoles, leading to the disassembly of the hydrogel (Figure 4b). By harvesting the spatiotemporal precision of the photoclick chemistry, they demonstrated the time-dependent, spatially controlled release of protein inducers such as horse serum to induce the differentiation of C2C12 cells and the spread of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) from their 3D encapsulation [39].

Concluding remarks

With several major advances in the last few years, including the design of tetrazole reagents that can be activated using a biocompatible light source, the design of robust, genetically encodable alkene reporters, and the improved understanding of the reaction mechanism, the tetrazole-alkene photoclick chemistry is poised to play an expanded role as a reactivity-based tool in biological systems. Besides its traditional use in protein labeling and biocompatible hydrogel formation/disassembly, other potential applications of the photoclick chemistry may include the multiplexed analysis of glycan dynamics on the basis of its mutual exclusivity with the tetrazine ligation [34] and the identification of drug targets and off-targets in cell- and tissue-based chemical proteomic analysis [40]. Because of its unique property of a spatiotemporal control, excellent reaction kinetics, and intrinsic “turn-on” fluorescence, the photoclick chemistry may also be useful in “no-wash” fluorescent labeling [41] of a subset of protein population in relatively transparent model organisms such as C. elegans [42] and subsequent study of the dynamics of this subpopulation in their native environment.

Highlights.

A light triggered in vivo chemistry

Fast reaction kinetics

Substrates are genetically encodable

Products are fluorescent

Spatial and temporal control

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (GM 085092) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1305826) for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Ramil CP, Lin Q. Bioorthogonal chemistry: Strategies and recent developments. Chem Commun. 2013;49:11007–11022. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44272a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tasdelen MA, Yagci Y. Light-induced click reactions. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2013;52:5930–5938. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clovis JS, Eckell A, Huisgen R, Sustmann R. 1.3-dipolare cycloadditionen, xxv. Der nachweis des freien diphenylnitrilimins als zwischenstufe bei cycloadditionen. Chem Ber. 1967;100:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Song W, Wang Y, Qu J, Madden MM, Lin Q. A photoinducible 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction for rapid, selective modification of tetrazole-containing proteins. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2008;47:2832–2835. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705805. This was the first report of the tetrazole-alkene photoclick chemistry as a new bioorthogonal reaction for biological applications.

- 5••.Song W, Wang Y, Qu J, Lin Q. Selective functionalization of a genetically encoded alkene-containing protein via “photoclick chemistry” in bacterial cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9654–9655. doi: 10.1021/ja803598e. This report established the suitability of photoclick chemistry for in vivo protein labeling.

- 6.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Click chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim RKV, Lin Q. Photoinducible bioorthogonal chemistry: A spatiotemporally controllable tool to visualize and perturb proteins in live cells. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:828–839. doi: 10.1021/ar200021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sesto A, Navarro M, Burslem F, Jorcano JL. Analysis of the ultraviolet b response in primary human keratinocytes using oligonucleotide microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2965–2970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052678999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An P, Yu Z, Lin Q. Design of oligothiophene-based tetrazoles for laser-triggered photoclick chemistry in living cells. Chem Commun. 2013;49:9920–9922. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45752d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Hu WJ, Song W, Lim RKV, Lin Q. Discovery of long-wavelength photoactivatable diaryltetrazoles for bioorthogonal 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions. Org Lett. 2008;10:3725–3728. doi: 10.1021/ol801350r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Z, Ho LY, Wang Z, Lin Q. Discovery of new photoactivatable diaryltetrazoles for photoclick chemistry via ‘scaffold hopping’. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5033–5036. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Song W, Hu WJ, Lin Q. Fast alkene functionalization in vivo by photoclick chemistry: Homo lifting of nitrile imine dipoles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5330–5333. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An P, Yu Z, Lin Q. Design and synthesis of laser-activatable tetrazoles for a fast and fluorogenic red-emitting 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. Org Lett. 2013;15:5496–5499. doi: 10.1021/ol402645q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Yu Z, Ohulchanskyy TY, An P, Prasad PN, Lin Q. Fluorogenic, two-photon-triggered photoclick chemistry in live mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16766–16769. doi: 10.1021/ja407867a. Tetrazoel reagents suitable for two-photon photoclick chemistry in mammalian cells were reported.

- 15.Furuta T, Wang SS, Dantzker JL, Dore TM, Bybee WJ, Callaway EM, Denk W, Tsien RY. Brominated 7-hydroxycoumarin-4-ylmethyls: Photolabile protecting groups with biologically useful cross-sections for two photon photolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1193–1200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Kaya E, Vrabel M, Deiml C, Prill S, Fluxa VS, Carell T. A genetically encoded norbornene amino acid for the mild and selective modification of proteins in a copper-free click reaction. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2012;51:4466–4469. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109252. This report described the use of hydrazonyl chloride as an alternative precursor for nitrile imine as well as the genetic encoding of a norbornene-modified lysine amino acid.

- 17•.Wang XS, Lee Y-J, Liu WR. The nitrilimine-alkene cycloaddition is an ultra rapid click reaction. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3176–3179. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48682f. The mechanism for the hydrazonyl chloride mediated nitrile imine-alkene cycloaddition was proposed, which has important implications for the photoclick chemistry as well.

- 18.Selvaraj R, Fox JM. trans-Cylooctene - a stable, voracious dienophile for bioorthogonal labeling. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Yu Z, Lin Q. Design of spiro[2.3]hex-1-ene, a genetically encodable double-strained alkene for superfast photoclick chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4153–4156. doi: 10.1021/ja5012542. An unprecented double-strained alkene reporter was designed and synthesized and the effect of chloride concentration on reaction kinetics was probed.

- 20.Rossin R, van den Bosch SM, ten Hoeve W, Carvelli M, Versteegen RM, Lub J, Robillard MS. Highly reactive trans-cyclooctene tags with improved stability for diels-alder chemistry in living systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:1210–1217. doi: 10.1021/bc400153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang K, Chin JW. Bioorthogonal reactions for labeling proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:16–20. doi: 10.1021/cb4009292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Lin Q. Synthesis and evaluation of photoreactive tetrazole amino acids. Org Lett. 2009;11:3570–3573. doi: 10.1021/ol901300h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Zhang W, Song W, Wang Y, Yu Z, Li J, Wu M, Wang L, Zang J, Lin Q. A biosynthetic route to photoclick chemistry on proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14812–14818. doi: 10.1021/ja104350y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y-J, Wu B, Raymond JE, Zeng Y, Fang X, Wooley KL, Liu WR. A genetically encoded acrylamide functionality. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1664–1670. doi: 10.1021/cb400267m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li F, Zhang H, Sun Y, Pan Y, Zhou J, Wang J. Expanding the genetic code for photoclick chemistry in e. Coli, mammalian cells, and a. Thaliana. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2013;52:9700–9704. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu Z, Lim RKV, Lin Q. Synthesis of macrocyclic tetrazoles for rapid photoinduced bioorthogonal 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:13325–13329. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang K, Davis L, Torres-Kolbus J, Chou C, Deiters A, Chin JW. Genetically encoded norbornene directs site-specific cellular protein labelling via a rapid bioorthogonal reaction. Nat Chem. 2012;4:298–304. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plass T, Milles S, Koehler C, Szymański J, Mueller R, Wießler M, Schultz C, Lemke EA. Amino acids for diels-alder reactions in living cells. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2012;124:4166–4170. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bianco A, Townsley FM, Greiss S, Lang K, Chin JW. Expanding the genetic code of drosophila melanogaster. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:748–750. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Yu Z, Pan Y, Wang Z, Wang J, Lin Q. Genetically encoded cyclopropene directs rapid, photoclick-chemistry-mediated protein labeling in mammalian cells. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2012;51:10600–10604. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205352. This report described the first use of photoclick chemsitry for site-specific protein labeling inside mammalian cells as well as the first use of cyclopropene as a privileged substrate for photoclick chemistry.

- 32.Patterson DM, Nazarova LA, Xie B, Kamber DN, Prescher JA. Functionalized cyclopropenes as bioorthogonal chemical reporters. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18638–18643. doi: 10.1021/ja3060436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, Seckute J, Cole CM, Devaraj NK. Live-cell imaging of cyclopropene tags with fluorogenic tetrazine cycloadditions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7476–7479. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamber DN, Nazarova LA, Liang Y, Lopez SA, Patterson DM, Shih H-W, Houk KN, Prescher JA. Isomeric cyclopropenes exhibit unique bioorthogonal reactivities. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13680–13683. doi: 10.1021/ja407737d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dijk M, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ, van Nostrum CF, Hennink WE. Synthesis and applications of biomedical and pharmaceutical polymers via click chemistry methodologies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:2001–2016. doi: 10.1021/bc900087a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan Y, Deng C, Cheng R, Meng F, Zhong Z. In situ forming hydrogels via catalyst-free and bioorthogonal “tetrazole-alkene” photo-click chemistry. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2814–2821. doi: 10.1021/bm400637s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alge DL, Anseth KS. Bioactive hydrogels: Lighting the way. Nat Mater. 2013;12:950–952. doi: 10.1038/nmat3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38•.Yu Z, Ho LY, Lin Q. Rapid, photoactivatable turn-on fluorescent probes based on an intramolecular photoclick reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11912–11915. doi: 10.1021/ja204758c. This report described the first application of the fluorogenic intramolecular photoclick chemistry in protein labeling inside mammalian cells.

- 39.He M, Li J, Tan S, Wang R, Zhang Y. Photodegradable supramolecular hydrogels with fluorescence turn-on reporter for photomodulation of cellular microenvironments. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18718–18721. doi: 10.1021/ja409000b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Z, Hao P, Li L, Tan CY, Cheng X, Chen GY, Sze SK, Shen HM, Yao SQ. Design and synthesis of minimalist terminal alkyne-containing diazirine photo-crosslinkers and their incorporation into kinase inhibitors for cell- and tissue-based proteome profiling. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:8551–8556. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizukami S, Watanabe S, Akimoto Y, Kikuchi K. No-wash protein labeling with designed fluorogenic probes and application to real-time pulse-chase analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1623–1629. doi: 10.1021/ja208290f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greiss S, Chin JW. Expanding the genetic code of an animal. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14196–14199. doi: 10.1021/ja2054034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]