Abstract

Background:

The expression of oestrogen receptor (ER) α characterises a subset of breast cancers associated with good response to endocrine therapy. However, the clinical significance of the second ER, ERβ1, and its splice variant ERβcx is still unclear.

Methods:

We here report an assessment of ERα, ERβ1 and ERβcx by immunohistochemistry using quantitative digital image analysis of 340 primary tumours and corresponding sentinel lymph nodes.

Results:

No differences were seen in ER levels in primary tumours vs lymph node metastases. ERβ1 and ERβcx were equally distributed among age groups and tumour histological grades. Loss of ERβ1 in the primary tumour was strongly associated with poor survival. Its prognostic impact was particularly evident in young patients and in high-grade tumours. The worst outcome was seen in the tumours lacking both ERα and ERβ1. ERβcx expression in the primary tumour correlated with a higher risk of lymph node metastasis, and with poor survival when expressed in sentinel node lymphocytes.

Conclusions:

Our study reveals highly significant although antagonising roles of ERβ1 and ERβcx in breast cancer. Consequently, we suggest that the histopathological assessment of ERβ1 is of value as a prognostic and potentially predictive biomarker.

Keywords: breast cancer, oestrogen receptor, oncology, pathology, endocrine therapy, biomarkers

Oestrogen receptor (ER)-mediated signalling has a fundamental role in breast cancer biology. In the majority of breast cancers, generally classified as the luminal subtypes, ER alpha (ERα), one of the members of the ER family, works as a central hub governing tumour cell proliferation and tumour progression (Sorlie et al, 2006; Ross-Innes et al, 2012).

Clinical trials have confirmed the predictive role of ERα as a biomarker in response to adjuvant endocrine therapy and thereby its association with favourable outcomes. Hence, tamoxifen has been shown to reduce the risk of any recurrence by 39% over a 10-year treatment period (Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) et al, 2011); however, the prognostic value of ERα seems to decrease after 5 years (Bentzon et al, 2008). This indicates that our understanding of ER signalling in breast cancer is still very limited. Since the discovery of a second ER, ER beta (ERβ) in 1996 (Kuiper et al, 1996), the general focus has been to decipher its role in biology and its corresponding clinical importance. ERα and ERβ are located on different chromosomes but show considerable homology. Both ERs bind tamoxifen and their main ligand, oestradiol, with similar affinity, but the differences within the ligand-binding pockets are significant enough to permit the synthesis of ERα- and ERβ-selective ligands (Kuiper et al, 1998). In terms of gene regulation, experiments performed on breast cancer cell lines in the presence of oestradiol indicate partly overlapping transcriptomes induced by the two ER subtypes (Chang et al, 2006). However, experimental studies in vitro and during tumour xenograft growth have shown opposing roles of the two receptors in terms of proliferation (Ström et al, 2004; Hartman et al, 2006). Contributing to the complex picture of ERβ signalling is the presence of several splice variants. The full-length ERβ is known as ERβ1 whereas the best characterised splice variant in breast cancer is ERβcx (also known as ERβ2; Ogawa et al, 1998). We now know that ERβ is expressed in the epithelium and stroma of normal as well as malignant mammary gland and mediates oestrogen response. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies indicate an association of ERβ expression with ERα-positive tumours and/or progesterone receptor (PR) status (Omoto et al, 2002; Fuqua et al, 2003). However, these studies were in part performed with pan-specific antibodies detecting all ERβ splice variants, including ERβcx. Later on, the roles of different ERβ splice variants have been dissected by the use of monoclonal C-terminus-targeted ERβ antibodies. It now appears that ERβ expression is associated with tamoxifen response, particularly within ERα-negative tumours (Gruvberger-Saal et al, 2007; Honma et al, 2008). Other researchers have been unable to confirm this association and instead report an association between ERβcx and ERα expression and a strong correlation of cytoplasmic ERβcx with poor survival (Shaaban et al, 2008). In a large population-based study, Marotti et al (2009) could confirm a positive correlation of ERβ1 expression with ERα, but not with survival; similar results were described by Borgquist et al (2008). One study has even shown an association of ERβ1 with poor prognosis, but only in lymph node-positive patients (Novelli et al, 2008). The majority of studies on larger patient populations have been performed by IHC on tissue microarrays (TMAs), a suboptimal platform for investigating heterogeneously expressed proteins. In the present study, we characterised ERβ1 and ERβcx and re-evaluated ERα expression by IHC of whole tumour sections from 340 patients with archived breast tumours and corresponding sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs).

Materials and methods

Study population and follow-up

The study cohort was identified from the patient registry at the Department of Pathology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Only patients who had undergone sentinel node biopsy (SNB) from 2001 to 2006 were included. All patients had a preoperative diagnosis of breast cancer and a clinically negative axilla. A subset of the cohort originated from a prospective study evaluating the oncological safety of SNB, the results of which have been published elsewhere (Andersson et al, 2012). The surgery was performed at either Karolinska University Hospital, South General Hospital or at Sofiahemmet Hospital, all in the Stockholm area. Routinely, patients were followed up annually for 5–10 years, and then reintroduced into the national mammography-screening programme. All recurrences within the Stockholm area are routinely referred back to the Department of Oncology at Karolinska University Hospital where the study has been performed. Patients who had moved away from the Stockholm County during follow-up were censored at the time of their deregistration.

Clinicopathological parameters and data on received adjuvant therapy were extracted from patient medical records. As some of the routine assessments such as PR and proliferation markers changed during the period, cut-offs employed at the time of diagnosis were used. Oestrogen receptor α was because if its central role in this study, however, re-evaluated throughout using IHC. Depending on tumour characteristics and stage of the disease, patients were treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy. The occurrence of local, regional or distant relapse, death, breast cancer-specific death and the dates of last follow-up were collected by assessing the medical records of each patient. Permits were obtained from the regional ethics board at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm (2012/90-31/2) and from the biobank at Karolinska University Hospital.

Specimen selection and immunohistochemistry

From each patient, one formalin-fixed paraffin tissue block of the primary tumour and one block of the matching SLN were identified. The sections were cut at 4-μm thickness and mounted. Immunohistochemistry was performed either on an Autostainer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; ERβ1) or on IntelliPath FLX (BioCare medical, Concord, CA, USA; ERα and ERβcx) according to the protocols and reagents provided by the manufacturers (BioCare medical and Dako), together with negative and positive controls. Heat-induced antigen retrieval in high pH solution was performed using a PT-linker (Dako) at 97°C for 20 min. The slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the primary monoclonal antibodies. Anti-ERβ1 (clone PPG5/10; Dako) 1 : 50, anti-ERβcx (clone 57/3; AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) 1 : 200 and anti-ERα (clone NCL-L-ER-6F11; Novocastra, Wetzlar, Germany) 1 : 200 antibodies were used. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used to detect primary antibody binding and haematoxylin as counterstaining.

Digitalisation of slides and image analysis

To set appropriate intensity cut-offs for the digital scoring, a subset of tumours and SLNs were first scored manually by two independent researchers for ERα, ERβ1 (GR and JH) and ERβcx (GR and GMK) in the following compartments: primary tumour, SLN metastasis, if present, and lymphocytes residing in the SLN. The Allred scoring system was used for the manual scoring. The method has been adapted to evaluate and quantify different proteins using IHC (Fuqua et al, 2003; Rosin et al, 2012). When the two researchers did not agree on the score, they re-evaluated the section together until an agreement could be reached. All slides were digitally scanned using a Pannoramic MIDI or Pannoramic 250 Flash (3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary). The Pannoramic viewer 1.15.2 software (3DHistech) was used for viewing the scanned images together with the built-in image analysis application, NuclearQuant (3DHistech), which has been validated and shown to be reproducible in the detection of ER in breast cancer (Krecsák et al, 2011). The software quantifies both the frequency and intensity of nuclear staining with DAB. Detection thresholds for the size, circularity and differences in contrast of the nuclei can be adjusted to distinguish cancer cells from other cell types such as fibroblasts or lymphocytes. The frequency score was based on the Allred system (Harvey et al, 1999), where a score between 0 and 5 is given depending on the frequency of positive cells (0%=0, <1%=1, 1% to <10%=2, 10% to <33%=3, 33% to <66%=4 and ⩾66%=5). The cut-off for the intensity (0 to 255) can also be changed to adjust the threshold to divide the nuclei stained into four different scoring categories (‘no positive nuclei'=0, ‘low intensity'=1, ‘moderate intensity'=2 and ‘high intensity'=3). The cut-offs were adjusted in a stepwise manner until the manual scoring and digital scoring matched on most occasions. The specific intensity threshold settings were for ERβ1: 0, ⩾175; 1, <175 and ⩾125; 2, <125 and ⩾80; 3, <80; for ERα: 0, ⩾170; 1, <170 and ⩾120; 2, <120 and ⩾70; 3, <70 and for ERβcx: 0, ⩾177; 1, <177 and ⩾130; 2, <130 and ⩾70; 3, <70. The frequency and intensity scores were then combined into a final score ranging from 0 to 8 (excluding 1). For all sections, three representative areas of invasive tumour were annotated and then subjected to image analysis. Only nuclear ER staining was analysed. When possible, each of the three areas contained at least 1000 nuclei. An average score of 4 or higher was considered as positive ER expression, corresponding to 10% positive cells with weak intensity, a cut-off that has been used in several reports (Mann et al, 2001; Honma et al, 2008).

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, continuous variables are presented as median (range), while categorical variables are presented as numbers of cases and corresponding percentages. The Pearson's Chi-square test was used to test the hypothesis of equal distribution of ER expression in categorical variables (positive vs negative). For the evaluation of ER status in node-negative vs node-positive patients, the Pearson's Chi-square test was supplemented by additional logistic regression in order to estimate the odds ratio for the presence of metastasis in different ER status groups. For the testing of distribution of ER expression (positive vs negative) in paired samples, such as primary tumours and their corresponding SLNs, the McNemar test was applied for categorical variables.

Estimation of 10-year survival rates was performed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. For the analysis of overall survival, follow-up time was calculated from the date of primary surgery until death of any cause or the date of medical record review, as medical records are directly linked to the national death registry. For the analysis of breast cancer-specific survival, follow-up time was from the date of primary surgery until death caused by breast cancer or the last recorded follow-up visit as documented in medical records at the department of oncology. All patients who died with metastasised breast cancer were considered to have died of the disease. For the analysis of disease-free survival, follow-up time was recorded from the date of primary surgery until the date of any relapse or until the last recorded follow-up visit. The influence of ER status on survival was tested using the log-rank test within the Kaplan–Meier model. As endocrine treatment was assumed to strongly affect survival analysis regarding ER expression, analyses were also adjusted for any endocrine treatment by adding this information as strata into the Kaplan–Meier model. For the comparative analysis of the impact of known risk factors on survival rates and their comparison with the impact of ER receptor status, both uni- and multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed and results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical computations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21. A P-value of ⩽0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 340 breast cancer patients operated between January 2001 and December 2006 were included. Of these, 322 tumours were stained and analysed for ERα, 316 for ERβ1 and 315 for ERβcx (see Supplementary Figure 1 for representative IHC stainings). Only nuclear staining of ERα, ERβ1 and ERβcx was analysed. Overall, 11 patients had no available tumour results of all three ERs, however, they were still included in the cohort since they had ER data from SLNs. Three patients had missing tumour data on ERα and ERβ1, three patients on ERα and ERβcx, and two patients on ERβ1 and ERβcx. Patient and tumour characteristics are presented in Table 1. Median follow-up for disease-free and breast cancer-specific survival was 81 months (range 0–148). Median follow-up for overall survival was 115 months (range 2–152). Thirty-six patients had died during the follow-up period, 16 of whom had died of breast cancer. Recurrences were found in 35 patients, sometimes multiple. In total, 10 local, 10 regional and 22 distant relapses were recorded. Ten patients developed contralateral breast cancer during the follow-up period, which was not considered a relapse. The Kaplan–Meier estimate of overall survival for the entire cohort was 83.9%, breast cancer-specific survival 92.1% and disease-free survival 81.6%. Adjuvant endocrine treatment had been given to 268 patients (78.8%) and chemotherapy to 132 patients (39.8%).

Table 1. Patient and tumour characteristics of 340 breast cancer samples divided according to ERβ1 status and for all patients.

| Clinicopathological variables | All patients | ERβ1 positive | ERβ1 negative |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics | |||

| Number | 340 | 241 (76.3)a | 75 (23.7)a |

| Age (years)b | 58 (23–86) | 58 (23–86) | 58 (32–82) |

| Tumour diameter (mm)b |

15 (1–73) |

15 (1–73) |

15 (4–50) |

|

T stage (mm) | |||

| T1 (⩽20) | 224 (66.5) | 155 (65.1) | 54 (72.0) |

| T2 (21–50) | 103 (30.6) | 75 (31.5) | 19 (25.3) |

| T3 (>50) | 10 (3.0) | 8 (3.4) | 2 (2.7) |

| Missing |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

Histological type | |||

| Ductal | 264 (78.6) | 181 (76.4) | 62 (82.6) |

| Lobular | 57 (16.9) | 45 (19.0) | 9 (12.0) |

| Mixed | 9 (2.7) | 6 (2.5) | 3 (4.0) |

| Other | 6 (1.8) | 5 (2.1) | 1 (1.3) |

| Missing |

4 |

4 |

0 |

|

ERα staus | |||

| Positive | 258 (80.1) | 197 (82.4) | 52 (71.2) |

| Negative | 64 (19.1) | 42 (17.6) | 21 (28.8) |

| Missing |

18 |

3 |

2 |

|

ERβcx staus | |||

| Positive | 279 (88.6) | 210 (90.1) | 58 (81.7) |

| Negative | 36 (11.4) | 23 (9.9) | 13 (18.3) |

| Missing |

25 |

8 |

4 |

|

PR status | |||

| Positive | 249 (73.9) | 182 (76.2) | 49 (66.2) |

| Negative | 88 (26.1) | 57 (23.8) | 25 (33.8) |

| Missing |

3 |

3 |

1 |

|

Elston histological grading | |||

| 1 | 89 (26.4) | 60 (25.2) | 22 (29.3) |

| 2 | 171 (50.7) | 126 (52.9) | 37 (49.3) |

| 3 | 77 (22.9) | 52 (21.8) | 16 (21.3) |

| Missing |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

Proliferation | |||

| Low | 221 (66.4) | 159 (67.4) | 47 (64.4) |

| High | 112 (33.6) | 77 (32.6) | 26 (35.6) |

| Missing |

7 |

236 |

2 |

|

Sentinel lymph node status | |||

| N0 | 195 (57.4) | 134 (55.6) | 46 (61.3) |

| N1 |

145 (42.6) |

107 (44.4) |

29 (38.7) |

|

Adjuvant treatment | |||

| Chemotherapy | 132 (39.8) | 95 (39.4) | 30 (40.0) |

| Radiotherapy | 250 (75.3) | 182 (77.4) | 52 (71.2) |

| All endocrine treatment | 268 (80.7) | 195 (83.0) | 55 (75.3) |

| Oestrogen receptor antagonist | 152 (44.7) | 110 (45.6) | 29 (38.7) |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 63 (18.5) | 40 (16.6) | 20 (26.7) |

| Combined endocrine treatment |

53 (15.6) |

45 (18.6) |

6 (8.0) |

|

ERα/PR status | |||

| Positive/positive | 207 (67.0) | 165 (69.6) | 42 (58.3) |

| Positive/negative | 40 (12.9) | 31 (13.1) | 9 (12.5) |

| Negative/positive | 21 (6.8) | 15 (6.3) | 6 (8.3) |

| Negative/negative | 41 (13.3) | 26 (11.0) | 15 (20.8) |

| Missing |

31 |

4 |

3 |

|

ERα/PR statusc |

All patientsc |

ERβcx positive |

ERβcx negative |

| Positive/positive | 208 (67.5) | 186 (68.1) | 22 (62.9) |

| Positive/negative | 39 (12.7) | 37 (13.6) | 2 (5.7) |

| Negative/positive | 22 (7.1) | 19 (7.0) | 3 (8.6) |

| Negative/negative | 39 (12.7) | 31 (11.4) | 8 (22.9) |

| Missing | 32 | 6 | 1 |

Abbreviations: ER=oestrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor. Data were collected from patient medical records, except for ERα, ERβ1 and ERβcx, which were evaluated within this study using immunohistochemistry. All numbers are cases (%) if not stated otherwise.

Twenty-four patients had missing ERβ1 classification.

Median (range).

Note that data presented below is on ERβcx expression.

Oestrogen receptor status in different age groups and tumour histological grades

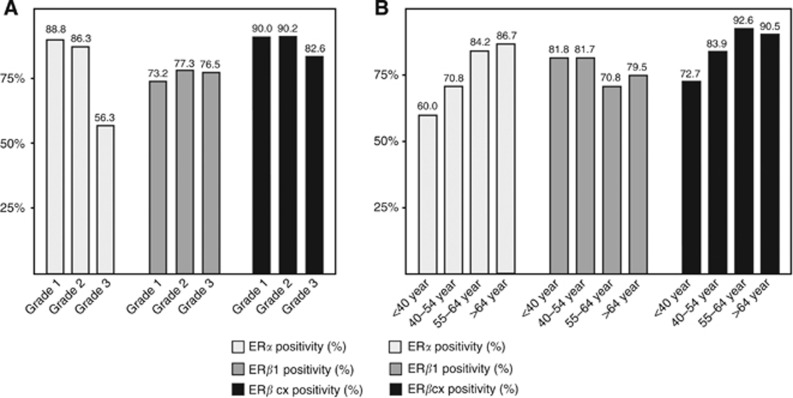

A cut-off of 10% was used to distinguish ER-positive from ER-negative tumours. As shown in Figure 1A, the percentage of ERα-positive tumours increased significantly with lower Elston–Ellis histological grade (P<0.001). ERβcx positivity followed a similar pattern but without reaching statistical significance (P=0.23). ERβ1, however, had an equal distribution in all tumour grades (P=0.771). Patients were divided into four age groups: <40 years (N=12), 40–54 years (N=104), 55–64 years (N=141) and ⩾65 years (N=81), to study age-related changes in ER positivity. As shown in Figure 1B, there was a significant increase in ERα-positive tumours with increasing age (P=0.011). There was a similar but non-significant trend for ERβcx positivity (P=0.062) with increased age category. Again ERβ1 showed a different expression pattern, where the positive tumours were equally distributed among all age groups (P=0.22).

Figure 1.

ER expression among different age groups and histological grades. (A) ERα positivity decreased with higher Elston–Ellis histological grade (white; P<0.001, N=80, 168, and 71). ERβcx showed a similar trend, however not significant (black; P=0.23, N=80, 163, and 69). ERβ1 was equally distributed among all three grades (grey; P=0.771, N=82, 163, and 68). (B) Patients were divided into four different age groups according to age at diagnosis, <40, 40–54, 55–64, and ⩾65 years. ERα (white) positivity was lowest in the youngest age group and increased with age (P=0.011, N=10, 96, 139, and 75). A similar trend was seen with ERβcx (black), however not reaching significance (P=0.062, N=11, 93, 135, and 73). ERβ1 was equally distributed along all age groups (grey; P=0.221, N=11, 93, 137, and 74). Numbers above bars reflect percentage of positive tumours.

Oestrogen receptor status in primary tumour and synchronous lymph node metastasis

The ER status of primary tumours did not differ significantly compared to their paired synchronous SLN metastases for any of the ERs: ERα (P=0.33), ERβ1 (P=1.0) and ERβcx (P=0.13). However, the proportion of ERβcx-positive tumours was higher in node-positive than node-negative patients (P=0.021; Table 2). This was confirmed by logistic regression, which resulted in an odds ratio of 2.54 (95% CI 1.15–5.61) for synchronous SLN metastasis in ERβcx-positive compared to negative cases. No difference in risk of SLN metastasis was seen in patients with ERα- or ERβ1-positive primary tumours.

Table 2. Oestrogen receptor (ER) α, ERβ1 and ERβcx expression in node-positive vs node-negative primary breast cancer.

| Primary tumour node negative | Primary tumour node positive | |

|---|---|---|

|

ERα | ||

| Negative |

35 (19.3) |

29 (20.6) |

| Positive |

146 (80.7) |

112 (79.4) |

|

P-value |

0.784 |

|

|

ERβ1 | ||

| Negative | 46 (25.6) | 29 (21.3) |

| Positive |

134 (74.4) |

107 (78.7) |

|

P-value |

0.382 |

|

|

ERβcx | ||

| Negative | 27 (15.2) | 9 (6.6) |

| Positive |

151 (84.8) |

128 (93.4) |

| P-value | 0.018* | |

Abbreviation: SLN=sentinel lymph node. The expression of ERβcx was significantly higher in the primary tumours of patients with SLN metastasis. This was not observed for ERα or ERβ. SLN negative N=195, SLN positive N=145. Pearson's Chi-square test. *P<0.05.

ERβ1 expression in the primary tumour strongly affects survival

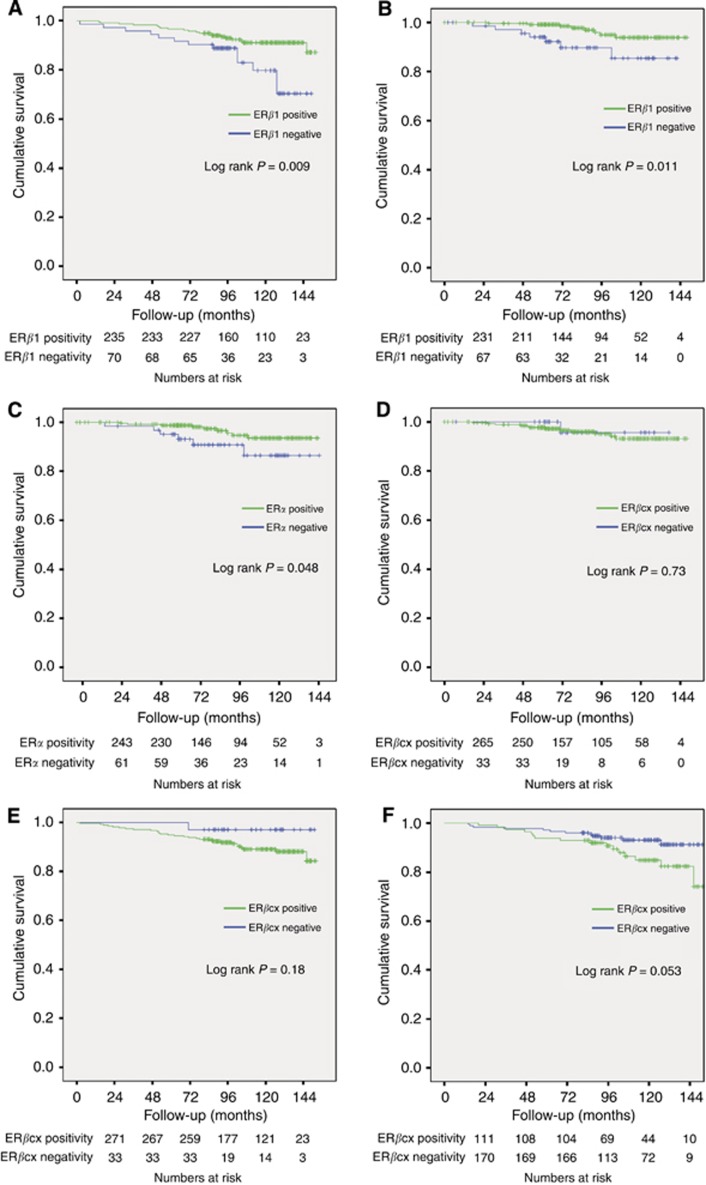

Ten-year overall survival was significantly lower in women with ERβ1-negative tumours (79.7% vs 91.1%, log rank P=0.009, Figure 2A) with a HR of 2.48 (95% CI 1.23–5.01). The corresponding figures for patients receiving adjuvant endocrine treatment were 88.7% vs 92.0% and for untreated patients 48.6% vs 92.4% (endocrine treatment-adjusted log rank P=0.005). No differences were seen when controlling for different types of endocrine treatment, such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. When primary tumours were stratified according to histological grades, 10-year overall survival was significantly worse for women with ERβ1-negative tumours of high grade compared to patients with ERβ1-positive high-grade tumours (60% vs 87.8%, log rank P=0.008). There was no significant survival difference with regard to ERβ1 expression within grade 1 and grade 2 tumours. The prognostic potential of ERβ1 was also compared within the four age groups described above. Although the youngest age group included too few patients for subgroup analysis, 10-year overall survival was significantly lower in women with ERβ1-negative tumours aged 40–54 and 55–64 years than in their ERβ1-positive counterparts (80% vs 98.7%, log rank P=0.001 and 84.7% vs 91.5%, log rank P=0.042). No significant survival difference in regard to ERβ1 status was seen in elderly women (>64 years).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots of overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival for ER expression in primary tumour and sentinel node lymphocytes. (A) There was a higher overall survival in patients with ERβ1-positive tumours (green) compared to ERβ1-negative (blue; log rank P=0.009). (B) The same was seen for breast cancer-specific survival for ERβ1-positive tumours (log rank P=0.011). (C) Breast cancer-specific survival was higher in patients with ERα-positive tumours (log rank P=0.048). (D) Breast cancer-specific survival did not differ between patients with ERβcx-positive or -negative tumours (log rank P=0.73). (E) There was a trend towards better overall survival in patients with ERβcx-negative tumours; however, this did not reach statistical significance (log rank P=0.18). (F) Patients with ERβcx-negative lymphocytes in the sentinel node showed a non-significant trend towards better overall survival (log rank P=0.053). Numbers at risk at each time point are given below each subfigure.

We also examined 10-year breast cancer-specific survival. This was significantly lower in women with ERβ1-negative tumours (85.4% vs 97.7%, log rank P=0.011; Figure 2B) with a HR of 3.44 (95% CI 1.24–9.49). The corresponding figures for patients given adjuvant endocrine treatment were 92.6% vs 93.9% and for untreated patients 59.9% vs 93.4% (endocrine treatment-adjusted log rank P=0.020). Also for breast cancer-specific survival, no differences were seen when controlling for different types of endocrine treatment. When stratifying by grade, 10-year breast cancer-specific survival was significantly lower in high-grade ERβ1-negative tumours compared with high-grade ERβ1-positive tumours (58.2% vs 88.2%, log rank P=0.036). Again, no difference was seen within lower histological grades. Similarly to overall survival, a lower 10-year breast cancer-specific survival was seen in women aged 40–54 years with ERβ1-negative tumours than in those with ERβ1-positive tumours (76.4% vs 98.1%, log rank P=0.001). There were no differences in breast cancer-specific survival within the two higher age groups (55–64 and >64 years).

ERα-positive tumours were associated with better breast cancer-specific survival (log rank P=0.048, Figure 2C) but not overall survival (log rank P=0.20). There was no significant association between ERβcx status in the primary tumour and overall or breast cancer-specific survival (Figure 2D and E), and no significant patterns were observed when stratifying for histological grades and age groups. None of the analysed ERs affected disease-free survival.

All potential prognostic variables were tested using univariable Cox regression analysis. Significant univariable factors were entered into a multivariable Cox regression model (Supplementary Table 1). As there were few patients in the youngest age group, no 95% CIs could be calculated for this specific group. In the multivariable model, loss of ERβ1 was associated with worse prognosis with a HR of 2.40 (95% CI 1.16–4.94). Also the loss of PR (HR 3.38, 95% CI 1.76–6.50), older age (>65 years) and advanced nodal stage (HR 3.77, 95% CI 1.54–9.19) remained independent of prognostic factors for overall survival. For breast cancer-specific survival, only ERβ1 (HR=3.38, 95% CI 1.09–10.45) and advanced nodal stage (HR=11.64, 95% CI 2.97–45.63) remained independent prognostic factors.

ER marker combinations affect breast cancer-specific and overall survival

Four combinations of intratumoural ERα and ERβ1 expression were created: ERα+/ERβ1+ (N=197), ERα+/ERβ1− (N=52), ERα−/ERβ1+ (N=42) and ERα−/ERβ1− (N=21). Differential 10-year overall survival differed significantly between these four groups with 91.4%, 85.4%, 90.0% and 75.6%, respectively (log rank P=0.050; Table 3). The same pattern was seen for 10-year breast cancer-specific survival rates of 93.9%, 91.0%, 93.6% and 72.1%, respectively (log rank P=0.009). Interestingly, these differences lost their significance when adjusting for any endocrine treatment, however, significance was retained when adjusted only for ER antagonist-containing postoperative therapy (e.g., tamoxifen; log rank P=0.032 and 0.031). Corresponding groups were created for ERβ1 and ERβcx (N=210 (ERβ1+/ERβcx+), 23 (ERβ1+/ERβcx−), 58 (ERβ1−/ERβcx+) and 13 (ERβ1−/ERβcx−)); in these groups, 10-year overall survival was 92.0%, 95.5%, 78.1% and 100%, respectively (log rank P=0.011). Rates for 10-year breast cancer-specific survival were 95.9%, 92.3%, 80.0% and 100%, respectively (log rank P=0.001). Adjusting for any endocrine treatment or for ER antagonists retained similar results (log rank P=0.006 and 0.007 for overall survival and P=0.002 and 0.003 for breast cancer-specific survival). Similar analyses of combinations of ERα and ERβcx expression did not render any significant associations with survival.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of ER co-expression in regard to OS and BCSS.

| ERβ1 positive | ERβ1 negative | |

|---|---|---|

| 10-year OS | ||

| ERα positive (%) | 91.4 | 85.4 |

| ERα negative (%) |

90.0 |

75.6 |

|

P-value |

0.050* |

|

| 10-year BCSS | ||

| ERα positive (%) | 93.9 | 91.0 |

| ERα negative (%) |

93.6 |

72.1 |

|

P-value |

0.009* |

|

| |

ERβcx positive |

ERβcx negative |

| 10-year OS | ||

| ERβ1 positive (%) | 92.0 | 95.5 |

| ERβ1 negative (%) |

78.1 |

100 |

|

P-value |

0.011* |

|

| 10-year BCSS | ||

| ERβ1 positive (%) | 95.9 | 92.3 |

| ERβ1 negative (%) |

80.0 |

100 |

|

P-value |

0.001* |

|

| 10-year OS | ||

| ERα positive (%) | 90.4 | 100 |

| ERα negative (%) |

84.6 |

90.0 |

|

P-value |

0.283 |

|

| 10-year BCSS | ||

| ERα positive (%) | 94.7 | 100 |

| ERα negative (%) |

86.0 |

85.7 |

| P-value | 0.093 | |

Abbreviations: BCSS=breast cancer-specific survival; ER=oestrogen receptor; OS=overall survival. The highest 10-year OS/BCSS was seen in ERα+/ERβ1+ tumours. Either ERα+/ERβ1− or ERα−/ERβ1+ was also associated with better prognosis, compared to double negative tumours (ERα−/ERβ1− that had the worst prognosis for both OS and BCSS. For ERβ and ERβcx co-expression, the worst 10-year OS/BCSS was seen in patients with ERβ1−/ERβcx+ tumours, compared to ERβ1+/ERβcx+, ERβ1+/ERβcx− and ERβ1−/ERβcx−. No significant differences in 10-year OS or BCSS were seen when comparing the co-expression of ERα and ERβcx. *P<0.05.

ERβcx expression in SLN lymphocytes is more common in node positivity and affects overall survival

ERβ1 and ERβcx positivity of lymphocytes residing in the SLN was seen in 202 out of 285 (70.9%) and 116 out of 292 (39.7%) patients, respectively. In contrast, ERα positivity in these cells was an extremely rare event with only one positive out of 248 cases (0.4%). ERβcx positivity in SLN lymphocytes was more common in node-positive than node-negative patients (57 out of 125 (45.6%) vs 59 out of 167 (35.3%)), even though this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.076). This trend was supported by the fact that patients with ERβcx positivity in their SLN had a higher mean number of axillary lymph node metastases (1.4) than those with ERβcx negativity (0.9; P=0.055). Ten-year overall survival was 93.0% for patients with ERβcx negativity in their SLN lymphocytes, as compared with 84.8% in those with ERβcx SLN lymphocyte positivity (log rank P=0.053, Figure 2F). Interestingly, this finding turned significant when adjusting for adjuvant endocrine therapy (log rank P=0.039). There was no effect of ERβcx SLN lymphocyte status on breast cancer-specific survival or on disease-free survival.

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that ERβ1 positivity within the primary tumour is an independent marker for good outcome, more powerful than ERα, which is classically associated with increased survival after adjuvant endocrine therapy. ERβ1 expression remained an independent prognostic marker for both overall and breast cancer survival in a multivariable Cox regression model, which strengthens the prognostic value of the receptor. The number of events in our cohort during follow-up period was small due to the generally good prognosis of breast cancer today and considering that included patients were clinically node negative. It has been shown, however, that survival analysis can be reliable with even as little as five events per variable within the Cox regression model. This is especially evident when the association is plausible and hypothesised a priori (Vittinghoff and McCulloch, 2007). When performing survival analysis in breast cancer while studying ERs it is important with sufficient follow-up due to the risk of late recurrences. The follow-up for breast cancer-specific survival was shorter than for overall survival due to their definitions specified in the Statistics section. However, since any recurrent breast cancer cases were referred back to the department where this study was performed, it is unlikely that such cases were missed. Thus, follow-up for breast cancer-specific survival and disease-free survival is probably underestimated. When we stratified patients for endocrine treatment, the survival was similarly high in patients with ERβ1-positive tumours. This is somewhat contradicting when compared with the results of Honma et al (2008), where the increase in survival was only seen in ERβ1-positive patients treated with tamoxifen for >2 years. Our group of endocrine-treated women, however, received tamoxifen and/or aromatase inhibitors usually for 5 years, which may perhaps explain the differences in survival. When we examined survival regarding the co-expression of ERα and ERβ1, patients who were either double or single positive had an equally good prognosis, meaning that ERβ1 is a potential biomarker for distinguishing between patients with good or bad prognosis in ERα-negative tumours, generally considered as a group of patients with poor prognosis. ERβ1 and ERβcx co-expression was associated with survival in a similar manner, again the lowest survival was seen in the ERβ1-negative tumours. Intriguingly, these tumours were also ERβcx-positive. ERβcx is thought to affect ER function through negative regulation by heterodimerisation, mainly with ERα, causing degradation of the receptor complex and therefore a decrease of ERα level (Zhao et al, 2007). This mechanism may result in a completely ER-negative tumour (ERα− and ERβ1−). Therefore, this tumour could be less sensitive to endocrine therapy and perhaps more responsive to chemotherapy. As described earlier it is important to remember that the stratification and subgroup analysis of the co-expression data is performed on a small cohort and with few events, which merits caution when interpreting these results. However, we believe that the findings are both clinically and biologically relevant, but need further validation.

ERβ1 seems to be present in tumours in patients from all age groups, whereas ERα expression is usually less common in younger women. Most interestingly, the negative prognostic significance of the lack of ERβ1 expression in the primary tumour is particularly strong in younger age groups and in tumours of high histological grades. Therefore, ERβ should be considered a valuable prognostic biomarker and perhaps a therapeutical target in younger women in whom triple-negative breast cancer (absence of ERα, PR and HER2) is more common. Tamoxifen and other current endocrine therapies such as aromatase inhibitors, however, are designed to treat ERα-expressing cancers and might not be the optimal therapy for targeting ERβ1. Our data suggest that the examination of ERβ1 status should have an additional prognostic value during routine pathological examination of breast cancer, but not as a biomarker for endocrine responsiveness within ERα-negative cases as described elsewhere (Gruvberger-Saal et al, 2007; Honma et al, 2008). Further research is needed to identify the ideal ERβ1-targeting therapy and to validate our findings.

Although several prospective investigations on ERβ isoforms in breast cancer have been performed, the potential association with clinicopathological parameters and survival remains unclear. The expression of the different ERβ isoforms is a result of alternative splicing at the C-terminus; consequently, antibodies raised against the N-terminus will inevitably quantitate the total ERβ level. This may cause a false view of the isoform-specific expression. In our study, we analysed ERβ1 expression with a widely cited, well-validated C-terminal monoclonal antibody (Skliris et al, 2002; Carder et al, 2005; Weitsman et al, 2006; Novelli et al, 2008). As mentioned, ERβ has been described as an anti-proliferative, tumour-suppressive receptor within breast cancer cells in vitro (Hartman et al, 2009). Consequently, it has been hypothesised that ERβ should be downregulated during breast cancer progression (Roger et al, 2001). However, paired primary tumours and corresponding metastatic lesions are extremely scarce materials and the hypothesis is thus hard to prove. Often, the presence of locoregional lymph node metastases are used as a surrogate parameter, as they are one of the strongest risk factors for breast cancer death and distant metastases (Fisher et al, 1983; Andersson et al, 2010). In a study on 50 patients, Gschwantler-Kaulich et al (2011) observed that compared to the primary tumour, there was a reduction in both ERα and ERβ levels in axillary lymph node metastases. In our analysis, ER status differed between primary tumour and corresponding lymph node metastases in several patients, even though we could not identify any changes in the overall pattern of ER status. This discrepancy is probably explained by the fact that Gschwantler-Kaulich et al used TMAs with 1 mm cores while our analysis was based on whole sections. It is evident that intratumoural ER levels are heterogeneously expressed, hence, IHC on TMAs may not be an optimal method for ER assessment of breast cancer specimens. Furthermore, to reduce variation and bias in our study, all IHC stainings were assessed by computer-assisted image analysis (see Materials and Methods section) in a blinded manner. This method, if correctly performed, is able to reduce both intra- and interobserver variation in biomarker assessments (Krecsák et al, 2011). Our analysis further showed that patients with ERβcx-positive primary tumours had an increased risk of lymph node metastasis. Nonetheless, the ER status of the corresponding lymph node metastasis did not correlate to outcome.

Oestrogen receptors, expressed in lymphocytes, are important in the maturation of B cells and play a crucial role in the peripheral immune system; this effect is mediated by both ERα and ERβ (Shim et al, 2006; Hill et al, 2011). Within the stroma of mammary gland and tumour adjacent tissue, ERβ is the predominating ER (Speirs et al, 2002). In the majority of our patients, we observed that lymphocytes within the SLNs express ERβ1 (70.9%) while a minority expressed ERβcx (39.4%) and <1% expressed ERα. We found that lymphocytes within lymph nodes containing metastatic breast cancer cells express higher levels of ERβcx. In patients treated with endocrine therapy, ERβcx-positive SLN lymphocytes indicated a poor prognosis and were furthermore associated with shorter 10-year overall survival. Our data imply that ERβcx within SLN lymphocytes may govern a yet unknown mechanism of breast cancer progression. Since the lymphocytes expressed little ERα, the tumourigenic function could perhaps be mediated through heterodimerisation and inhibition of ERβ1.

In summary, this study indicates that ERβ1 and the ERβ splice variant ERβcx have several important roles during breast tumourigenesis. In the primary tumour, ERβ1 was associated with good outcome and probably has a tumour-suppressive function. ERβcx, however, seems to play the most important role in regional lymph nodes where its presence in lymphocytes correlated to overall survival in breast cancer patients through an as yet unknown mechanism. The analysis of ERβ1 and ERβcx by IHC provides useful clinical information, especially for younger women and tumours of high histological grade. Further research is needed to understand how to pharmaceutically target the individual ER subtypes in breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Viberg and Anna-Lena Borg for their excellent technical support during the study, Dr Eva af Trampe for assisting in the evaluation of the medical records and Professor Jan-Åke Gustafsson at the University of Houston, Texas, USA, for valuable comments. We also thank the Swedish Research Council (VR), the Linnaeus Cancer Risk Prediction (CRisP), the Breast Cancer Theme Center (BRECT), the Swedish Cancer Society, the research funds at Radiumhemmet and Swedish Society for Medical Research (SSMF) for providing funding for the experiments in the study.

Author contributions

JH, JdB, JB and JF designed research; GR, JH, JdB and GMK performed research; JdB and GR analysed data; JdB, GR and JH wrote the paper; JH led the project.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersson Y, de Boniface J, Jönsson PE, Ingvar C, Liljegren G, Bergkvist L, Frisell J, Swedish Breast Cancer Group, Swedish Society of Breast Surgeons Axillary recurrence rate 5 years after negative sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:226–231. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Y, Frisell J, Sylvan M, de Boniface J, Bergkvist L. Breast cancer survival in relation to the metastatic tumor burden in axillary lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2868–2873. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzon N, Düring M, Rasmussen BB, Mouridsen H, Kroman N. Prognostic effect of estrogen receptor status across age in primary breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1089–1094. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgquist S, Holm C, Stendahl M, Anagnostaki L, Landberg G, Jirström K. Oestrogen receptors alpha and beta show different associations to clinicopathological parameters and their co-expression might predict a better response to endocrine treatment in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:197–203. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PJ, Murphy CE, Dervan P, Kennedy M, McCann A, Saunders PTK, Shaaban AM, Foster CS, Witton CJ, Bartlett JMS, Walker RA, Speirs V. A multi-centre investigation towards reaching a consensus on the immunohistochemical detection of ERβ in archival formalin-fixed paraffin embedded human breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-4262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Frasor J, Komm B, Katzenellenbogen BS. Impact of estrogen receptor beta on gene networks regulated by estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4831–4842. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Darby S, McGale P, Pan HC, Taylor C, Wang YC, Dowsett M, Ingle J, Peto R. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Bauer M, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Fisher ER, Cruz AB, Foster R, Gardner B, Lerner H, Margolese R. Relation of number of positive axillary nodes to the prognosis of patients with primary breast cancer. an NSABP update. Cancer. 1983;52:1551–1557. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831101)52:9<1551::aid-cncr2820520902>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua SAW, Schiff R, Parra I, Moore JT, Mohsin SK, Osborne CK, Clark GM, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor beta protein in human breast cancer: correlation with clinical tumor parameters. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2434–2439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruvberger-Saal SK, Bendahl PO, Saal LH, Laakso M, Hegardt C, Eden P, Peterson C, Malmstrom P, Isola J, Borg A, Fernö M. Estrogen receptor expression is associated with tamoxifen response in ER-negative breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1987–1994. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwantler-Kaulich D, Fink-Retter A, Czerwenka K, Hudelist G, Kaulich A, Kubista E, Singer CF. Differential expression pattern of estrogen receptors, aromatase, and sulfotransferase in breast cancer tissue and corresponding lymph node metastases. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:501–508. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman J, Lindberg K, Morani A, Inzunza J, Ström A, Gustafsson J-Å. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits angiogenesis and growth of T47D breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11207–11213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman J, Ström A, Gustafsson J-Å. Estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer—diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Steroids. 2009;74:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill L, Jeganathan V, Chinnasamy P, Grimaldi C, Diamond B. Differential roles of estrogen receptors α and β in control of B-cell maturation and selection. Mol Med. 2011;17:211–220. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma N, Horii R, Iwase T, Saji S, Younes M, Takubo K, Matsuura M, Ito Y, Akiyama F, Sakamoto G. Clinical importance of estrogen receptor-beta evaluation in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3727–3734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krecsák L, Micsik T, Kiszler G, Krenács T, Szabó D, Jónás V, Császár G, Czuni L, Gurzó P, Ficsor L, Molnár B. Technical note on the validation of a semi-automated image analysis software application for estrogen and progesterone receptor detection in breast cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, Corton JC, Safe SH, van der Saag PT, van der Burg B, Gustafsson JA. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–4263. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann S, Laucirica R, Carlson N, Younes PS, Ali N, Younes A, Li Y, Younes M. Estrogen receptor beta expression in invasive breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:113–118. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotti JD, Collins LC, Hu R, Tamimi RM. Estrogen receptor. Mod Pathol. 2009;23:197–204. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli F, Milella M, Melucci E, Di Benedetto A, Sperduti I, Perrone-Donnorso R, Perracchio L, Venturo I, Nisticò C, Fabi A, Buglioni S, Natali PG, Mottolese M. A divergent role for estrogen receptor-beta in node-positive and node-negative breast cancer classified according to molecular subtypes: an observational prospective study. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R74. doi: 10.1186/bcr2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Orimo A, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Muramatsu M. Molecular cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor betacx: a potential inhibitor ofestrogen action in human. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3505–3512. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.15.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto Y, Kobayashi S, Inoue S, Ogawa S, Toyama T, Yamashita H, Muramatsu M, Gustafsson JA, Iwase H. Evaluation of oestrogen receptor beta wild-type and variant protein expression, and relationship with clinicopathological factors in breast cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:380–386. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger P, Sahla ME, Mäkelä S, Gustafsson JA, Baldet P, Rochefort H. Decreased expression of estrogen receptor beta protein in proliferative preinvasive mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2537–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin G, Hannelius U, Lindström L, Hall P, Bergh J, Hartman J, Kere J. The dyslexia candidate gene DYX1C1 is a potential marker of poor survival in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Teschendorff AE, Holmes KA, Ali HR, Dunning MJ, Brown GD, Gojis O, Ellis IO, Green AR, Ali S, Chin S-F, Palmieri C, Caldas C, Carroll JS. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban AM, Green AR, Karthik S, Alizadeh Y, Hughes TA, Harkins L, Ellis IO, Robertson JF, Paish EC, Saunders PTK, Groome NP, Speirs V. Nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of ER 1, ER 2, and ER 5 identifies distinct prognostic outcome for breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5228–5235. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim G-J, Gherman D, Kim H-J, Omoto Y, Iwase H, Bouton D, Kis LL, Andersson CT, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Differential expression of oestrogen receptors in human secondary lymphoid tissues. J Pathol. 2006;208:408–414. doi: 10.1002/path.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skliris GP, Parkes AT, Limer JL, Burdall SE, Carder PJ, Speirs V. Evaluation of seven oestrogen receptor beta antibodies for immunohistochemistry, western blotting, and flow cytometry in human breast tissue. J Pathol. 2002;197:155–162. doi: 10.1002/path.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Wang Y, Xiao C, Johnsen H, Naume B, Samaha RR, Børresen-Dale A-L. Distinct molecular mechanisms underlying clinically relevant subtypes of breast cancer: gene expression analyses across three different platforms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs V, Skliris GP, Burdall SE, Carder PJ. Distinct expression patterns of ER alpha and ER beta in normal human mammary gland. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:371–374. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.5.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström A, Hartman J, Foster JS, Kietz S, Wimalasena J, Gustafsson J-Å. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits 17beta-estradiol-stimulated proliferation of the breast cancer cell line T47D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308319100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitsman GE, Skliris G, Ung K, Peng B, Younes M, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Assessment of multiple different estrogen receptor-beta antibodies for their ability to immunoprecipitate under chromatin immunoprecipitation conditions. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;100:23–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Matthews J, Tujague M, Wan J, Strom A, Toresson G, Lam EW-F, Cheng G, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. Estrogen receptor beta2 negatively regulates the transactivation of estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3955–3962. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.