Abstract

Background:

Patients presenting with mass lesions of liver and gallbladder are a common occurrence in a cancer hospital in north central part of India. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) serves as first line of pathological investigations, but there are pros and cons involved.

Aim:

The main objective of the present study was to establish adequacy of the procedure and to find out diagnostic pitfalls. An attempt was made to analyze inconclusive and inadequate aspirations.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 400 consecutive fine-needle aspirates of liver, belonging to 328 cases over a period of 2 years, were analyzed. Hematoxylin and eosin and May-Grόnwald-Giemsa stains were used. Chi-square test was carried out to compare significant degree of difference in different kind of diagnosis.

Results:

Out of 400 aspirations, 289 (72.2%) were adequate, 75 (18.7%), inconclusive and 36 (9%), inadequate. Among positive aspirations the most common was metastatic adenocarcinoma, 128 (44.2%). The positive diagnosis and adequate aspirations were significantly high (P < 0.0001). Major differential diagnostic problems were: Distinguishing the poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma from the metastatic adenocarcinoma; and leukemia/lymphoma from other malignant round cell tumors. Common diagnostic pitfalls were repeated aspirations from the necrotic area and aspiration of atypical, disorganized and reactive hepatocytes, adjacent to a metastasis. No complications were observed.

Conclusion:

FNAC can be used successfully for the diagnosis of liver and gallbladder lesions, thus avoiding open biopsy. Study indicates the potential of using FNAC in clinical intervention where the incidence of gall-bladder and liver cancer is very high and open biopsy and surgery are not an option.

Keywords: Cytology liver, fine-needle aspiration cytology, gall-bladder carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver metastasis

Introduction

Most of the mass lesions of liver and gallbladder discovered clinically or by imaging techniques are easily assessable to fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). It is important to establish primary or metastatic nature of the lesion and in case of the latter to comment upon probable site of the primary tumor.[1,2] Moreover, among gastrointestinal tract (GIT) cancers, gall-bladder cancer incidence is very high in north central India. Late diagnosis and socio-economic status of patients in a hospital set up like this make it difficult to operate or even go for open biopsy.[3] A quick FNAC diagnosis saves valuable time and enables the clinician to plan treatment accordingly. In the present study, we have evaluated a large number of aspirations for diagnosis of liver and gallbladder cancer. This reflects the adequacy of the procedure along with difficulties in diagnosis in a hospital set up like ours.

Materials and Methods

A total of 400 percutaneous trans-hepatic aspirations, belonging to 328 cases of liver and gallbladder lesions, were received in a super specialty cancer hospital, over a period of 2 years.

Percutaneous aspirations were performed using a 22-gauge needle and a 20 mL disposable syringe, with or without ultrasound guidance. Air-dried smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa and alcohol fixed smears with hematoxylin and eosin. Diagnostic criteria laid down by Orell et al., 1992[4] were utilized while analyzing smears.

Results

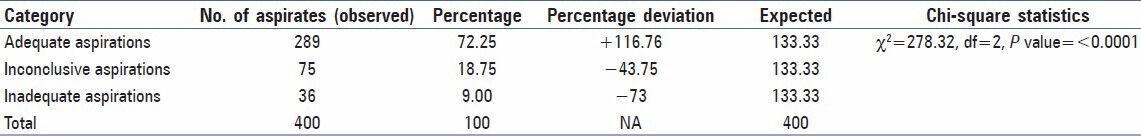

A total of 400 percutaneous FNAC aspirations studied belonged to 328 cases of liver and gallbladder lesions. These aspirations were categorized into three groups [Table 1]: Group 1-adequate aspirations (72.25%), when smears were suggestive of a definitive diagnosis. Group 2-inconclusive aspirations (l8.75%), when smears had some cells, not sufficient enough for definitive diagnosis, and Group 3-inadequate aspirations (9.00%), when smears did not show any epithelial cells. The percentage deviation and Chi-square statistics showed [Table 1] that the probability of getting adequate aspirations was significantly high (P ≤ 0.0001) in the present study.

Table 1.

Chi-square distribution of different categories of aspiration (total number = 400) and goodness of fit

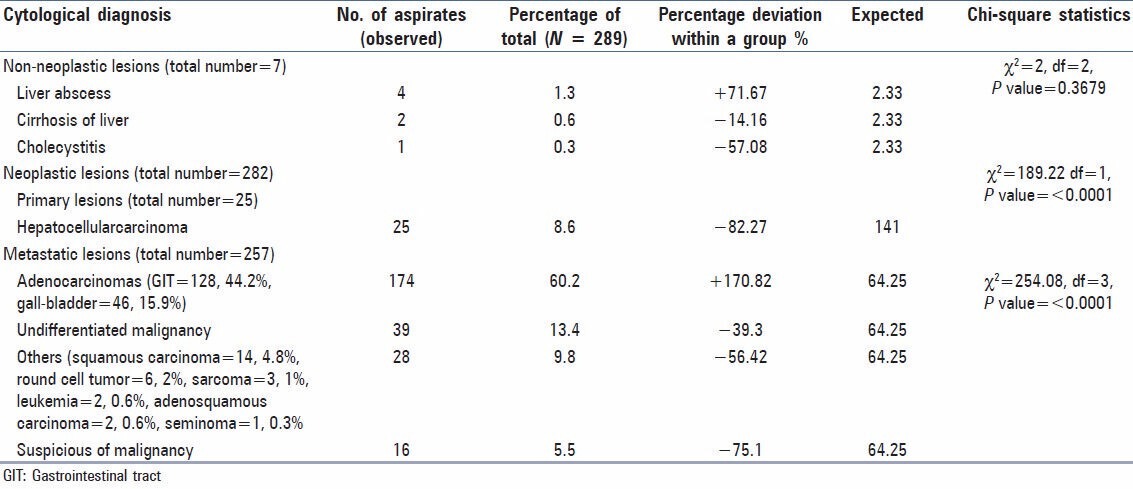

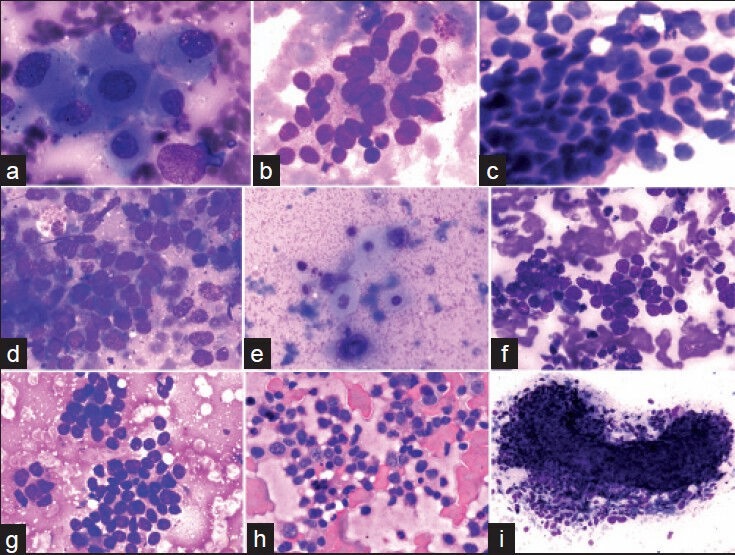

Adequate aspirations (289, 72.25%) included non-neoplastic cases (7, 2.2%) and neoplastic cases (282, 96.9%). The identification of neoplastic cases is statistically significant with P < 0.0001 at degree of freedom 1 having Chi-square value of 259.78. The distribution of adequate aspirations is given in Table 2. The statistical distribution of non-neoplastic lesions is non-significant due to very small number of cases in the category. The distribution of primary (25, 8.6%) and metastatic (257, 88.9%) shows that a significant number of metastatic lesions can be identified with the adequate aspirations (Chi-square statistic = 189.2 at the degree of freedom 1 and P < 0.0001). Adenocarcinomas contributed majority (174 of 257 cases) of metastatic neoplastic lesions. Metastatic adenocarcinoma from GIT formed the majority of cases (128), followed by gall-bladder carcinoma (46) and undifferentiated malignancy (39). The Chi-square distribution shows that FNAC can significantly differentiate these cytological categories from each other [Table 2] abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, polygonal shape and large vesicular nuclei with prominent central nucleoli characterized hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells were arranged in sheets and clusters with acinar pattern or in trabecular pattern. Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions were also present [Figure 1a]. Metastatic adenocarcinoma cells from gastrointestinal tumor had abundant cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei in loose clusters and groups. Metachromatic cytoplasmic granules were present in some cases [Figure 1b]. Metastasis from a case of ductal carcinoma breast showed cohesive clusters of cells with moderately pleomorphic overlapping nuclei [Figure 1c]. Gallbladder adenosquamous carcinoma had sheets of adenocarcinoma cells [Figure 1d] characterized by mildly pleomorphic cells with a moderate amount of cytoplasm and discretely present malignant squamous cells [Figure 1e] with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant glassy to blue cytoplasm. At places, adenocarcinomatous cells were tightly pressed against each other and had faceted nuclei. Nucleoli were prominent in high-grade tumors. Tight clusters of hyperchromatic cells with scanty cytoplasm and nuclear molding were seen in small cell carcinoma from lung [Figure 1f]. Smears from liver mass of a 2-year-old female patient showed small monomorphic malignant cells with round hyperchromatic nuclei and scanty cytoplasm. Rosette-like spaces were evident. Metastatic neuroblastoma was suspected [Figure 1g]. Discretely present centrocytic-centroblastic cells with prominent nucleoli suggested a non-Hodgkins lymphoma [Figure 1h]. Lymphoid globules could be appreciated better in Giemsa stained smears. Metastatic sarcomas showed a cohesive tissue fragment of ovoid to spindly cells with indistinct cytoplasm [Figure 1i]. Metastatic germ cell tumor cells from a case of testicular mass had clusters of moderately pleomorphic cells with discernible cytoplasm. Lymphocytes were also present.

Table 2.

Chi-square distribution of various cytological diagnosis in adequate aspirations (total number = 289)

Figure 1.

(a) A cluster of large pleomorphic cells with abundant cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli in an aspirate from a case of hepatocellular carcinoma (MGG, ×400). (b) Mucus secreting adenocarcinomatous metastasis showing a loose cluster of markedly pleomorphic vesicular cells with abundant cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders (MGG, ×00). (c) Metastatic ductal carcinoma breast showing cohesive cell cluster. Nuclei are vesicular and overlapping (H and E, ×400). (d) A cohesive cluster of mildly pleomorphic hyperchromatic adenocarcinomatous cells with minimal cytoplasm from a case of gallbladder adenosquamous carcinoma (MGG, ×400). (e) Malignant squamous cells from the above case have hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant glassy-blue cytoplasm (MGG, ×400). (f) Metastatic small cell anaplastic carcinoma from lung showing a cohesive cluster of hyperchromatic cells; nuclear molding can be appreciated (MGG, ×400). (g) Metastatic malignant round cell tumor showing a cluster of round-ovoid cells with scanty cytoplasm. Rosettes are evident (MGG, ×400). (h) Infiltration of Non-Hodgkins lymphoma cells: Discretely present large cells have irregular nuclear membrane and prominent nucleoli (H and E, ×400). (i) Metastatic spindle cell sarcoma showing a “microbiopsy” of ovoid — spindle cells; discrete cells present at the periphery (MGG, ×100)

Among non-neoplastic cases liver abscess had mixed inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphs and lymphocytes in a necrotic background. The aspirates of liver cirrhosis showed clusters of benign hepatocytes with endothelial investment. Cholecystitis smears showed mixed inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphs and lymphocytes. A case of liver abscess, at repeat aspiration turned out to be suspicious for malignancy. A smear initially suggested to be cirrhosis with atypical cells, on repeat aspiration, turned out to be metastatic adenocarcinoma.

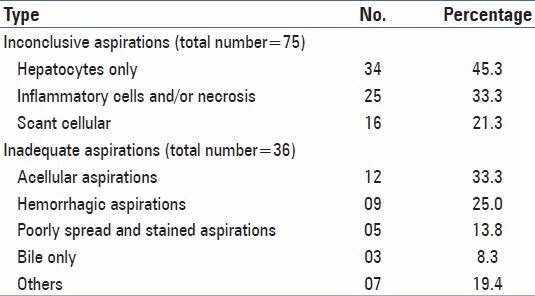

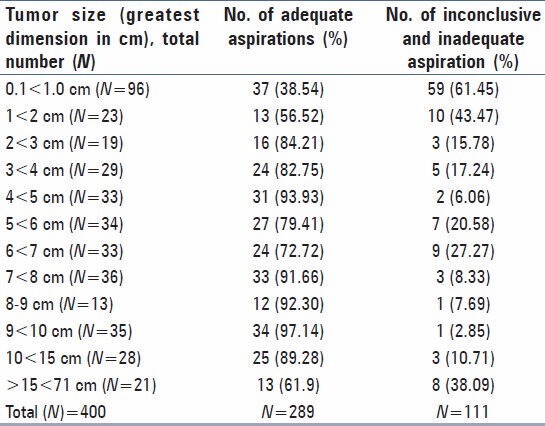

Table 3 shows categorization of inconclusive smears, about 45.3% had only hepatocytes and inadequate smears, about 33.3% were acellular. An association between tumor size and adequacy of FNAC aspirations is found with highest number of inadequate and inconclusive aspirations (61.45%) in the tumor size (0.1 < 1.0 cm) followed by 43.47% in the group (1 < 2 cm). A Chi-square statistics with a degree of freedom (12) with Chi-square value (95.107) shows that the tumor size can have significant level of association (P < 0.001) with the positive outcome of FNAC [Table 4].

Table 3.

Distribution of inconclusive/inadequate aspirations

Table 4.

Distribution of adequate, inconclusive and inadequate aspirations according to tumor size

Discussion

FNAC is gaining popularity as a means of diagnosing mass lesions in intra-abdominal organs. FNAC has now proved to be superior to core-needle or open biopsy is terms of cost, procedure, associated morbidity and early diagnosis.-[3] Single or multiple focal abnormalities demonstrated by palpation, nuclear scan, computed tomography (CT) scan or ultra-sonography constitute the main indications for the FNAC of the liver.[4,5]

In various studies, sensitivity for diagnosis of hepatic malignancy ranges from 75.34% to 93%.[6,7] In the present study, adequate aspirations were only 72%, as most of them were blind aspirations. Various authors have reported specificity to be ranging from 69% to 100%.[8,9,10] In our study, the accuracy rate for adequate aspirations, in correlation with clinical and skiagram, ultra-sonography, and CT scan findings, was 99%. As reported by Ramdas and Chopra[10] no false positive cases were reported in this study too.

In a series of 1383 cases of FNAC of liver, by Tao et al.,[11] 1037 (75%) were metastatic cancers. Some other workers have reported metastatic liver malignancy as high as 90%.[4] In the present study, metastases were 74.9%; most common were metastatic adenocarcinoma (from GIT) (44.2%); gallbladder adenocarcinoma was second most common, constituting 15.9%.

Ramdas and Chopra[10] did not observe any complications following FNAC. Other authors have reported complications like fatal bleeding in a case of chronic liver disease, needle tract tumor seedling and biliary-venous fistula.[12,13] Lundqvist[14] reported only one significant complication, an intrahepatic hematoma, in 2600 Fine needle aspiration biopsies of the liver. We, however, did not observe any complication.

Table 3 shows distribution of inconclusive and inadequate aspirations. Repeat aspirations after initial report of inconclusive or inadequate aspiration yielded a positive diagnosis in a number of cases: 27 aspirations were repeated twice, 10 aspirations were repeated thrice and 2 aspirations were repeated 4 times. On the other hand, 11 aspirations repeated twice and 1 aspiration repeated thrice failed to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. The chance that a single puncture would procure a representative sample is 72.3%. For these cases, puncture with slight modification in the angle of approach, the chances are increased to 94% in experienced hands.[11] Similarly, a necrotic smear may represent a tumor and should be repeated.[1]

Diagnostic pitfalls of the present study include repeated necrotic aspirations misinterpreted as an abscess, disorganized hepatocytes and cholestasis from liver parenchyma adjacent to metastatic carcinoma misinterpreted as cirrhosis. Furthermore, differentiation of poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma presents a great challenge. Identification of tumor cells that resemble normal hepatocytes, presence of sinusoidal pattern or endothelial investment of tumor cell clusters could be of some help.[15]

In the present study as shown in the Table 4 and described above, the success of positive FNAC aspirations in the smallest tumor size group (0.1 < 1.0 cm) is 38.54% with highest percentage of inadequate aspirations (61.45%) in this group. Although, the most successful aspirations were from 9 < 10 cm (97.14%) followed by 4 < 5 cm (93.93%), there were significant numbers of adequate aspirations across different size of the tumors over 1 cm. It is reported in various other cancers that the tumor size influences the outcome of adequate FNAC aspirations.[16,17] There is little literary evidence of such findings in gall-bladder cancer lesions.

Thus, it is important that all the cytology smears are interpreted in correlation with relevant clinical and other investigatory findings and repeated whenever indicated, until a satisfactory sample is obtained. Moreover, the present observations can help the similar hospital settings in diagnosis of GIT cancers where open biopsy and surgery is not called for.

Acknowledgments

MAB acknowledges Senior Research Fellowship from Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi. Authors are thankful to technical staffs of Department of Pathology and Surgery, CHRI, Gwalior.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Mustafa A Barbhuiya is supported by a Senior Research Fellowship from Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi. Pramod K Tiwari acknowledges financial support as research grant from Madhya Pradesh Council of Science and Technology, Bhopal, MP, India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jambhekar NA, Saxena R, Krishnamurthy S, Bharadwaj R, Sheth A. Fine needle aspiration cytology of liver: An analysis of 530 cases. J Cytol. 1999;16:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li ZY, Liang QL, Chen GQ, Zhou Y, Liu QL. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver diagnosed by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology: A case report and review of the literature. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:392–7. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbhuiya MA, Singh TD, Poojary SS, Gupta S, Kakkar M, Shrivastav BR, et al. Gallbladder cancer incidence in Gwalior district of India: Five year trend based on registry of a regional cancer centre. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:249–57. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.176736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orell SR, Sterrett GF, Walters MN, Whitaker D. Manual and Atlas of Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology. 2nd ed. Hong Kong: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. Retroperitoneum, liver and spleen; pp. 217–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodd LG, Mooney EE, Layfield LJ, Nelson RC. Fine-needle aspiration of the liver and pancreas: A cytology primer for radiologists. Radiology. 1997;203:1–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herszenyi L, Farinati F, Cecchetto A, Marafin C, de Maria N, Cardin R, et al. Fine-needle biopsy in focal liver lesions: The usefulness of a screening programme and the role of cytology and microhistology. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah A, Jain GM. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the liver — A study of 518 cases. J Cytol. 2002;19:139–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenblatt R, Kutcher R, Moussouris HF, Schrieber K, Koss LG. Sonographically guided fine-needle aspiration of liver lesions. JAMA. 1982;248:1639–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwerk WB, Dürr HK, Schmitz-Moormann P. Ultrasound guided fine-needle biopsies in pancreatic and hepatic neoplasms. Gastrointest Radiol. 1983;8:219–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01948123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramdas A, Chopra R. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology of liver lesions. J Cytol. 2003;20:121–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao LC, Donat EE, Ho CS, McLoughlin MJ. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. Cytodiagnosis of hepatic cancer. Acta Cytol. 1979;23:287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mingoli A, Marzano M, Sgarzini G, Nardacchione F, Corzani F, Modini C. Fatal bleeding after fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:250–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel RI, Shapiro MJ. Biliary venous fistula: An unusual complication of fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:953–6. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundquist A. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy for cytodiagnosis of malignant tumour in the liver. Acta Med Scand. 1970;188:465–70. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1970.tb08069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilotti S, Rilke F, Claren R, Milella M, Lombardi L. Conclusive diagnosis of hepatic and pancreatic malignancies by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voit CA, van Akkooi AC, Eggermont AM, Schäfer-Hesterberg G, Kron M, Ulrich J, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of palpable and nonpalpable lymph nodes to detect metastatic melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1771–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willems SM, van Deurzen CH, van Diest PJ. Diagnosis of breast lesions: Fine-needle aspiration cytology or core needle biopsy. A review? J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:287–92. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]