Abstract

Pregnancy-associated gingivitis is a bacterial-induced inflammatory disease with a remarkably high prevalence ranging from 35% to 100% across studies. Yet little is known about the attendant mechanisms or diagnostic biomarkers that can help predict individual susceptibility for rational personalized medicine. We aimed to define inflammatory proteins in saliva, induced or inhibited by estradiol, as early diagnostic biomarkers or target proteins in relation to pregnancy-associated gingivitis. An in silico gene/protein interaction network model was developed by using the STITCH 3.1 with “experiments” and “databases” as input options and a confidence score of 0.700 (high confidence). Salivary estradiol, interleukin (IL)-1β and -8, myeloperoxidase (MPO), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, -8, and -9, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 levels from 30 women were measured prospectively three times during pregnancy and twice during postpartum. In silico analysis revealed that estradiol interacts with IL-1β and -8 by an activation link when the “actions view” was consulted. In saliva, estradiol concentrations associated positively with TIMP-1 and negatively with MPO and MMP-8 concentrations. When the gingival bleeding on probing percentage (BOP%) was included in the model as an effect modifier, the only association, a negative one, was found between estradiol and MMP-8. Throughout gestation, estradiol modulates the inflammatory response by inhibiting neutrophilic enzymes, such as MMP-8. The interactions between salivary degradative enzymes and proinflammatory cytokines during pregnancy suggest promising ways to identify candidate biomarkers for pregnancy-associated gingivitis, and for personalized medicine in the field of dentistry. Finally, we call for greater investments in, and action for biomarker research in periodontology and dentistry that have surprisingly lagged behind in personalized medicine compared to other fields, such as cancer research.

Introduction

Gender-related differences in the course of infection and inflammation have been intensively documented for many acute and chronic diseases (Baggio et al., 2013). Chief among the attendant mechanisms is the circulating and tissue concentrations of sex hormones. Epidemiological and immunological studies collectively lend evidence that female sex hormones play pivotal roles in cell proliferation, cytokine and enzyme secretion, differentiation and growth of cells beyond the reproductive organs, for example, in the periodontium (tooth-supporting tissues), including the gingival epithelium, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone (Straub, 2007).

In nonpregnant women, estrogen is found at very low concentrations in the circulation (10−9–10−12 mol/L); during pregnancy, however, estrogen secretion increases by 20–30-fold, with a peak at the end of the third trimester (Lipworth et al., 1999; Mariotti, 1994). The most potent form of estrogen is estradiol (17β-estradiol). Inhibition of bone resorption is considered a common immunomodulating effect of estrogen (Syed and Khosla, 2005), and suppression of inflammation due to estradiol has been documented (Nilsson, 2007). Proinflammatory effects of estrogen have also been studied, especially in the context of autoimmune diseases. According to recent studies, several factors, such as the cell types involved, duration, timing, and magnitude of estrogen stimulus, can affect the immunomodulating functions of this hormone (Novella et al., 2012; Straub, 2007). Estrogen enhances cellular proliferation in blood vessels, inhibits neutrophilic chemotaxis and enzyme activity, stimulates fibroblast proliferation, and alters collagen metabolism in periodontal tissues (Mamalis et al., 2011; Nebel, 2012; Straub, 2007). Periodontal tissues upregulate endothelial adhesion molecules, increase the secretion of chemotactic agents, and aggravate leukocyte chemotaxis as a response to bacterial challenge. Estrogen attenuates these critical steps of inflammation by inhibiting the secretion of adhesion molecules and chemokines (i.e., macrophage chemoattractant peptide-1 and interleukin (IL)-8, respectively) (Mamalis et al., 2011; Nebel et al., 2010; Su et al., 2008).

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes capable of degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) components (Sorsa et al., 2004). Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are endogenous inhibitors of MMPs in both normal and pathological processes. In pregnancy, elevated female sex hormone levels suppress the mother's own immune response, allowing the fetal survival (Chen et al., 2012). As gestation progresses, the adaptation of fetal membranes and cervix to uterine and fetal growth is regulated by the steady remodeling of the collagenous ECM by MMPs (Weiss et al., 2007). Due to their roles in cervical ripening and dilatation, and as well as membrane weakening and rupture, MMPs are essential in birth (Weiss et al., 2007). MMP-1, -2, and -3 are constitutively expressed during gestation, and the active labor induces the production of MMP-9 (Cockle et al., 2007). Pregnancy complications, including preterm birth, are related with aberrant ECM degradation by MMPs. Serum TIMP-1 and -2 levels are lower in preterm gestations compared to those at term, irrespective of labor status (Tency et al., 2012).

Pregnancy-associated gingivitis is a bacterial infection-induced inflammatory disease, affecting the gingiva, with a high prevalence of 35% to 100% (Hasson, 1960; Löe and Silness, 1963). The main difference between pregnancy-associated gingivitis and chronic dental plaque-induced gingivitis is the severity of inflammatory response against bacterial burden at the gingival margin. During pregnancy, the pronounced tissue response is clinically characterized by increased gingival swelling and bleeding tendency. Elevated female sex hormone concentrations in pregnant women seem to relate to the enhanced susceptibility to gingival inflammation (Ide and Papapanou, 2013) and growth of gram-negative anaerobes, especially Prevotella nigrescens (Gürsoy et al., 2009). However, there are no sufficient data to claim that the bacterial burden alone leads to pregnancy-associated gingivitis. Indeed, high levels of salivary estrogen in pregnancy are associated with the severity of gingival inflammation; subjects with high estradiol were more prone to develop gingivitis than those with low estradiol levels (Gürsoy et al., 2013). Despite increased susceptibility to gingival inflammation during pregnancy, no correlation between the levels of inflammatory biomarkers (elastase, MMP-2, -8, 9, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and TIMP-1), measured in gingival crevicular fluid or saliva, and the exacerbation and remission of gingival inflammation could be demonstrated in our previous studies (Gürsoy et al., 2010a; 2010b) without advanced analytical techniques. Inhibition of inflammatory cell functions by estrogen and enhanced inflammatory response during pregnancy stay as an unsolved dilemma.

After mapping of the human genome nearly 20 years ago, there has been great interest in understanding of complex molecular mechanisms in human diseases, and new methods to analyze gene expressions and DNA arrays have been developed actively. “Omics” technologies, including, but not limited to, genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, aim to identify the complex effects in the form of gene/protein expression profiles in health and disease (Özdemir, 2013). With the use of these methods, new insights are being gained into maternal metabolism during pregnancy and its relationship to outcomes at birth and in childhood (Lowe and Karban, 2014). In silico modeling and gene expression analyses have become an integral part of life sciences by guiding the researchers towards the selection of the most relevant targets, as well as protein–protein and compound–protein interactions in the context of any disease (i.e., approaches that our study group has successfully applied) (Zeidán-Chuliá et al., 2012; 2013a; 2013b; 2013c; 2014). By using in silico approaches, it is possible to generate a model of interactions based on experimental data, giving rise to new hypotheses that could be later tested with wet laboratory experiments.

In the present study, we hypothesized that interactions between estradiol and inflammatory markers, which can be defined by in silico analysis, also take part in the pathogenesis of pregnancy-associated gingivitis. If salivary biomarkers could be shown as target inflammatory proteins in silico and their relation to estradiol confirmed in vivo, this may lead to improved salivary detection for early diagnosis of pregnancy gingivitis and even to a pharmaceutical approach to regulate the production or activation of the responsible protein.

We first aimed to find in silico potential interactions between the selected inflammatory markers and estradiol. Second, we examined the landscape of interactions in the context of pregnancy by measuring these inflammatory markers and estradiol in salivary samples from pregnant women. In the validation assays, we utilized available data from our previously published articles, including salivary estradiol, MMP-2, -8, -9, TIMP-1, and MPO levels (Gürsoy et al., 2010b; 2013), in addition to the newly analyzed interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-8 levels.

Material and Methods

Network development

Proinflammatory cytokines and degradative enzymes relevant in periodontal disease pathogenesis, IL-1β and -8, MPO, MMP-2, -8, and -9, TIMP-1, as well as estradiol, were selected to create a network model of interactions. To achieve this goal, the database resource search tool, STITCH 3.1 (http://stitch.embl.de/) (Kuhn et al., 2008), was used by selecting exclusively “Databases” and “Experiments” as input options, a confidence score of 0.700 (high confidence), and a custom limit of “no more than 50 interactors.” STITCH 3.1 returned a network composed by 34 nodes (Table 1). The given links (protein–protein, compound–compound, and protein–compound) provided by STITCH 3.1 were saved in data files to be handled in the Medusa interface (Hooper and Bork, 2005). Proteins were identified by using the HUGO Gene Symbol (Eyre et al., 2006) and Ensembl protein ID (Birney et al., 2006). The complete list with gene symbols, compound names, and IDs (Ensembl protein IDs and Compound IDs) is provided in Table 1. By clicking the “Actions view” option of STITCH 3.1, a representation between the network nodes by either “activation,” “inhibition,” “binding,” “catalysis,” and “reaction” was developed and shown within the network in different colors.

Table 1.

Ensembl Protein and Compound Identifiers (ENSEMBL, ID, and CID, respectively) of the Components Belonging to In Silico Network Model of Interactions Between Estradiol and Selected Inflammatory Markers

| Network node | Description | ENSEMBL, ID, or CID |

|---|---|---|

| ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | ENSP00000257497 |

| CALML3 | Calmodulin-like 3 | ENSP00000315299 |

| Calcium | Ca2+ | CID271 |

| Estradiol | Estradiol (E2 or 17-estradiol, also oestradiol) is a sex hormone. Estradiol is abbreviated E2 as it has 2 hydroxyl groups in its molecular structure | CID450 |

| FGA | Fibrinogen alpha chain | ENSP00000306361 |

| FGB | Fibrinogen beta chain | ENSP00000306099 |

| FGG | Fibrinogen gamma chain | ENSP00000336829 |

| F2 | Coagulation factor II (thrombin) | ENSP00000308541 |

| F2R | Coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor | ENSP00000321326 |

| F9 | Coagulation factor IX | ENSP00000218099 |

| GP1BA | Glycoprotein Ib (platelet), alpha polypeptide | ENSP00000329380 |

| IL1B | Interleukin 1, beta | ENSP00000263341 |

| IL1RAP | Interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein | ENSP00000072516 |

| IL1RN | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | ENSP00000259206 |

| IL1R1 | Interleukin 1 receptor, type I | ENSP00000233946 |

| IL1R2 | Interleukin 1 receptor, type II | ENSP00000330959 |

| IL8 | Interleukin 8 | ENSP00000306512 |

| MBL2 | Mannose-binding lectin (protein C) 2, soluble (opsonic defect) | ENSP00000363079 |

| MMP2 | Matrix metallopeptidase 2 (gelatinase A, 72kDa gelatinase, 72kDa type IV collagenase) | ENSP00000219070 |

| MMP8 | Matrix metallopeptidase 8 (neutrophil collagenase) | ENSP00000236826 |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (gelatinase B, 92kDa gelatinase, 92kDa type IV collagenase) | ENSP00000361405 |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase | ENSP00000225275 |

| PPP3CA | Protein phosphatase 3 (formerly 2B), catalytic subunit, alpha isoform | ENSP00000378323 |

| PPP3R1 | Protein phosphatase 3 (formerly 2B), regulatory subunit B, alpha isoform | ENSP00000234310 |

| PRKCG | Protein kinase C, gamma | ENSP00000263431 |

| SERPINC1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade C (antithrombin), member 1 | ENSP00000356671 |

| SERPIND1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade D (heparin cofactor), member 1 | ENSP00000215727 |

| THBD | Thrombomodulin | ENSP00000366307 |

| TIMP1 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | ENSP00000218388 |

| TIMP2 | TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 2 | ENSP00000262768 |

| TNNI3 | Troponin I type 3 | ENSP00000341838 |

| TNNT2 | Troponin T type 2 | ENSP00000350511 |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor | ENSP00000261405 |

| YWHAZ | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, zeta polypeptide | ENSP00000309503 |

Study population

The study group consisted of 30 healthy (medically and periodontally), Caucasian, nonsmoking pregnant women (age range: 24–35 years). The additional inclusion criterion was to be at 10±1 weeks of pregnancy. The exclusion criteria were being a present active smoker, using systemic or topical antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory therapy within the previous 3 months, having a history of systemic disease, and poor oral hygiene, deep caries lesions, and/or remnant roots.

After being informed on the purpose and aims of the study, all study participants gave their written informed consent. The women had three visits during pregnancy, once per each trimester (at 12 to 14 weeks, 25 to 27 weeks, and at 34 to 38 weeks of pregnancy), and two postpartum visits (at 4 to 6 weeks after delivery, and after breastfeeding had ended). Out of the 30 pregnant women, 24 completed the follow-up period between October 2002 and October 2006, and 21 participated in each of the five visits. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical approval was obtained from the Helsinki University Central Hospital Obstetrics and Gynecology Ethics committee.

Clinical parameters

All clinical measurements were performed by the same dentist (MG).A calibration process, including two periodontal examinations at the same day, was performed on 10 subjects. The intra-examiner agreement was found to be very good according to the calculated Kappa scores (κ 0.853–0.897) (Gürsoy, 2012).

At each visit, bleeding on probing (BOP), as a marker of gingival inflammation, was measured from six sites per tooth, including all teeth, and scored dichotomously using a 0–1 measure presenting the absence or presence of bleeding, respectively.

Salivary measurements

At every study visit, paraffin-stimulated saliva was collected by expectoration for 5 min, placed into sterile eppendorf tubes, and transported to the Institute of Dentistry, Biomedicum, Helsinki, within 2 h. The samples were immediately frozen and stored at −20°C until assayed.

Salivary inflammatory marker and estradiol levels were determined using either flow cytometry-based Luminex technology, time-resolved immunofluorometric assay (IFMA), gelatin zymography, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Each determination was performed according to the test-specific protocol. The levels of MMP-2, -8, -9, MPO, TIMP-1, and estradiol in saliva were available from our previous publications, where applied methods have been described in detail (Gürsoy et al., 2010b; 2013). For the present study, two cytokines, IL-1β and IL-8, were examined by the commercially available Luminex kits (Milliplex Map Kit MPXHCYTO-60k, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were determined using the IBM SPSS statistics 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of the salivary markers were skewed; therefore nonparametric tests were applied. For descriptive analyses, the median values and median absolute deviations were calculated. Differences between the visits were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Linear mixed models were used to estimate the association between repeated measures of salivary inflammatory markers as dependent outcomes and salivary estradiol as an independent predictor variable. In addition, the models were controlled for the level of gingival inflammation (BOP%) as covariate. For each inflammatory marker, separate models were used and estradiol was taken as a fixed effect, either alone or together with BOP%. No random effect was defined. A statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

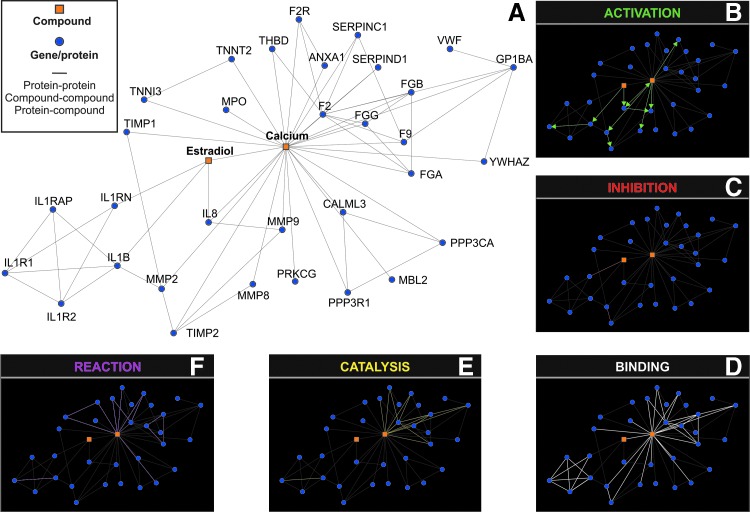

The in silico network model, representing the interactions between estradiol and inflammatory markers by using a confidence score of 0.700 (high confidence) and exclusively “Databases” and “Experiments” as input options, revealed the activation of IL-1β and IL-8 and the inhibition of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RN) by estradiol (Fig. 1A–C). No direct interconnection was detected by the resource search tool STITCH 3.1 between estradiol and MMPs; however, binding between estradiol and calcium as well as activation of MMP-2, -8, and -9 by calcium was revealed in silico. Neither activation nor inactivation was observed between calcium and TIMP-1 or MPO (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

In silico network model of the interactions between estradiol and selected inflammatory markers developed by using the STITCH 3.1 resource with “experiments” and “databases” as input options and a confidence score of 0.700 (high confidence) (A). “Actions view” representation between the network nodes by either “activation” (B), “inhibition” (C), “binding” (D), “catalysis” (E), and “reaction” (F) are shown within the network in different colors.

The mean age±SD of pregnant women was 29.3±2.8 years, and the mean number±SD of erupted teeth per individual was 28.5±1.4. All women lactated and the mean lactation period±SD was 38.7±19.2 months. During the follow-up, the mean±SD BOP% was 24.4±16.3 at first trimester, 33.7±13.2 at second trimester, 28.1±13.1 at third trimester, 17.3±12.5 after delivery, and 7.9±3.4 after lactation.

Salivary estradiol and inflammatory marker levels are given in Table 2. The levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, IL-1β, and IL-8 in saliva were steady during pregnancy and postpartum, whereas MMP-8 and MPO levels increased significantly after delivery. Salivary estradiol levels increased at each trimester of pregnancy and decreased significantly after delivery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Salivary Levels of Estradiol and Inflammatory Markers

| First trimester (n=29) | Second trimester (n=30) | Third trimester (n=26) | After delivery (n=28) | After lactation (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 20.1 (11.2) | 45.9 (14.5)a*** | 49.4 (15.9)b* | 2.1 (0.67)c*** | 2.7 (0.96) |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 8.1 (5.65) | 7.3 (5.45) | 8.6 (5.62) | 8.4 (5.84) | 4.9 (2.95) |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 297 (73.6) | 264.4 (73.5) | 282.2 (100) | 376.6 (201) | 338.4 (147) |

| MPO (ng/mL) | 459 (222) | 303.1 (168) | 318.8 (164) | 622.1 (290)c*** | 367.1 (157) |

| MMP-2 (IU) | 0.7 (0.22) | 0.7 (0.30) | 0.6 (0.23) | 0.8 (0.41) | 0.8 (0.40) |

| MMP-8 (ng/mL) | 240 (89.9) | 171.1 (94.1)a* | 143.5 (70.0) | 368.9 (188)c* | 279.5 (136) |

| MMP-9 (IU) | 5.9 (1.07) | 6.0 (0.84) | 6.2 (0.91) | 6.6 (0.65) | 6.5 (1.33) |

| TIMP-1 (ng/mL) | 81.3 (25.5) | 82.5 (34.9) | 84.0 (22.9) | 71.2 (30.8) | 99.9 (34.9) |

Data are given as medians and median absolute deviations (in parenthesis).

Different from first trimester; bDifferent from second trimester; cDifferent from third trimester.

p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

In longitudinal analysis of the associations between salivary estradiol and inflammatory markers, statistically significant negative associations were found between estradiol and the concentrations of MPO (p<0.05) and MMP-8 (p=0.001), while a positive association was detected between estradiol and TIMP-1 (< 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations [Estimate, (95% Confidence Interval Lower and Upper), p Value] Between Inflammatory Markers (Each Was Included Separately as Dependent Variable) and Estradiol (as an Independent Predictor Variable)

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | IL-8 (pg/mL) | MPO (ng/mL) | MMP-2 (IU) | MMP-8 (ng/mL) | MMP-9 (IU) | TIMP-1 (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 0.181 (−0.181–0.543), 0.324 | −0.499, (−1.755–0.756), 0.432 | −1.66, (−3.010–0.312), 0.016 | −0.001, (−0.004–0.002,) 0.417 | −2.474, (−3.861–1.086), 0.001 | −0.001, (−0.012–0.009), 0.759 | 0.207, (0.118–0.402), 0.038 |

p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant (indicated with bold).

After adjustment for BOP%, a negative association was found between the salivary concentrations of estradiol and MMP-8 (p=0.006). No significant associations between the salivary concentrations of estradiol and MPO or TIMP-1 were found (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations Between Estradiol and Inflammatory Markers, after Clinical Periodontal Status (Bleeding on Probing (BOP) %) Is Included into Model as Effect Modifier

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | IL-8 (pg/mL) | MPO (ng/mL) | MMP-2 (IU) | MMP-8 (ng/mL) | MMP-9 (IU) | TIMP-1 (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | −0.21, (−0.97–0.56), 0.594 | −1.71, (−4.61–1.19), 0.246 | −2.83, (−5.94–0.27), 0.074 | −0.002, (−0.01–0.004,) 0.544 | −4.60, (−7.83–1.37), 0.006 | −0.01, (−0.03–0.01), 0.291 | 0.28, (−0.16–0.74), 0.210 |

| BOP % | 0.288, (−0.81–1.38), 0.603 | −1.32, (5.19–2.56), 0.503 | 1.79, (−2.38–5.96), 0.398 | 0.001, (−0.01–0.01,) 0.806 | −1.45, (−5.81–2.91), 0.511 | −0.02, (−0.05–0.02), 0.330 | −0.48, (−1.10–0.12), 0.038 |

| Estradiol X BOP% | 0.011, (−0.013–0.034), 0.367 | 0.043, (−0.042–0.123), 0.317 | 0.026, (−0.07–1.12), 0.580 | 0.00002, (−0.00–0.00) 0.854 | 0.07, (−0.02–0.16), 0.143 | 0.0004, (−0.000–0.001), 0.247 | 0.0002, (−0.01–0.01), 0.976 |

Discussion

The present study aimed to characterize the landscape of interactions between estradiol and inflammatory markers in silico and evaluate the relevance of these observed interactions in salivary samples from pregnant women. While IL-1β and IL-8 activating and IL-1RN inhibiting properties of estradiol (present in our in silico model) were not detectable in saliva during or after pregnancy, salivary estradiol was negatively associated with salivary MMP-8 levels. Our in vivo results suggest that the inhibitory effect of estradiol on inflammation occurs through MMP-8, and this association is not affected by the presence of clinical inflammation as measured by BOP%.

In silico methods offer a “link” between different areas of research, such as biochemistry, biology, toxicology, pharmacology, and medicine. These methods include databases, similarity searching, quantitative structure–activity relationships, homology models, and other molecular modeling, pharmacophores, machine learning, data mining, network analysis tools as well as data analysis tools that use a computer (Ekins et al., 2007). According to the present in silico analysis, estradiol activates IL-1β and IL-8 and inhibits IL-1RN, while such a correlation between these markers was not seen in vivo. Downregulated Th1 and upregulated Th2 cytokine profiles seem to be characteristic for pregnancy (Wilder, 1998). The observation indicates that pregnant women with periodontitis (i.e., an advanced form of periodontal disease with irreversible destruction of tooth-supporting tissues, including collagen fibers and alveolar bone) could have an exacerbated inflammatory response. Serum IL-1β, IL-8, and estradiol levels have already been interrelated in the literature; for example, it has been claimed that increased serum IL-1β predicts ongoing pregnancy in subjects with controlled ovarian stimulation (Bonetti et al., 2010). In the present study, our in silico results represent the general landscape of interactions between estradiol and selected proteins, while in vivo results are shown specifically in pregnant women. We failed to find an association between the levels of tested cytokines and estradiol; one explanation could be that the increased gingival bleeding tendency during pregnancy is related to alternative pathways, such as the histamine–prostaglandin interaction cascade. An alternative cause for the discrepancy between the general landscape and pregnancy can be related to the long duration and high magnitude of estrogen stimulus during pregnancy, in contrast to the nonpregnant condition. Immune response is prone to the duration and magnitude of estrogen stimulus, for example, an oral estrogen application was found to increase serum IL-1β at first 4 months of therapy, with a fall of its level afterwards (Wilson et al., 2009).

In in vitro conditions, low concentrations of estradiol stimulate IL-1β secretion of monocytes, whereas high estradiol concentrations during pregnancy inhibit the secretion (Polan et al., 1988; 1989). Similar results have been noted also for IL-8. On one hand, estradiol increases IL-8 secretion in human breast tissues (Bendrik and Dabrosin, 2009) and upregulates IL-8 expression in human corneal epithelial cells (Suzuki and Sullivan, 2005). On the other hand, at pre-ovulatory to pregnancy levels, estradiol inhibits the secretion of IL-8 (Kanda and Watanabe 2001; Lin et al., 2004; Straub, 2007). It is herein likely that the relation between inflammatory cytokines and estradiol is concentration-dependent and does not necessarily follow the same course when nonpregnancy and pregnancy conditions are compared.

In the present study, one important finding in vivo was the relation seen between estradiol and MMP-8 concentrations in saliva, which was not shown in silico. Salivary MPO, MMP-2, -8, -9, and TIMP-1 have been found at lower levels in pregnant women in comparison to their controls (Clark et al., 1994; Gürsoy et al., 2010b). In saliva, levels of inflammatory markers are mainly determined by the oral inflammatory status; however, systemic conditions may also affect their levels (Gürsoy et al., 2011). In stimulated saliva, MPO and MMP-8 originate mainly from neutrophils, while resident cells of periodontium, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts are responsible for the secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9 into the oral cavity. TIMP-1 originates not only from gingival tissue or gingival crevicular fluid but also from the salivary glands, and thereby the gingival infection and inflammation are not the only effectors (Holten-Andersen et al., 2011). Estradiol receptors (ERs) α and β are present in salivary gland epithelial cells and carry immunoregulatory functions, including the inhibition of interferon-c-inducible expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (Tsinti et al., 2009). It was previously stated that the reduced salivary MMP-8 and MPO concentrations, in particular, but also that of MMP-9, in pregnant subjects are outcomes of impaired neutrophil functions during pregnancy (Gürsoy et al., 2010b). To our knowledge, there is no published information on the regulation of TIMP-1 secretion by estrogen receptors in healthy salivary gland tissues; however, it has been shown in breast cancer cells that estradiol affects MMP-9 and TIMP-1 expression via ERα status (Kousidou et al., 2008). In a study on ovariectomized rats, estrogen treatment improved the TIMP-1/MMP-9 balance (Voloshenyuk and Gardner, 2010). This balance is essential in maintaining the regeneration of connective tissue and is critically important for the regulation of delivery at the end of pregnancy. Based on our results, one could postulate that changes in salivary MMP-8 concentrations are explained by changes in estradiol concentrations. In silico, MMPs did not directly interconnect with estradiol, while calcium had a key role in this context. Calcium ions are required for the expression of MMP activity, and estrogen is able to regulate the MMP activity by altering intracellular calcium concentrations and reducing calcium influx in cells (Jiang et al., 1992). Although salivary calcium concentrations have been related to periodontal diseases (Kiss et al., 2010), it is not clear whether the activation of salivary MMPs is regulated by salivary calcium.

In our study, the effect of gingival inflammation, as defined by BOP%, was not tested in the in silico model. This may lead us to misinterpret the study outcomes, since the clinical status is generally associated with salivary biomarker levels. In the analysis of associations between estradiol and inflammatory markers, however, gingival inflammation was included into the model as an effect modifier. We have previously demonstrated that, despite the increase in the severity of gingival inflammation, salivary biomarker levels stay low and steady in pregnancy (Gürsoy et al., 2010b; 2013). Moreover, no correlation was found between the clinical status and biomarker levels in gingival crevicular fluid (Gürsoy et al., 2010a). Other inflammatory pathways may act as possible regulators of increased gingival inflammation during pregnancy.

Omics disciplines basically examine the related sets of biological molecules, either by assessing the static encoding of the genome (genomics) or by analyzing the temporal gene expressions (transcriptomics, proteomics). Personalized medicine and development of disease biomarkers belong to the aims of omics. Detection of new salivary biomarkers with the aid of omics technologies can help dental professionals to easily diagnose periodontal diseases, and even identify healing and predict treatment outcomes (see reviews by Cuevas-Córdoba and Santiago-García, 2014; Grant, 2012). The interactions between salivary degradative enzymes and proinflammatory cytokines during pregnancy suggest promising ways to identify candidate biomarkers for pregnancy-associated gingivitis, and for personalized medicine in the field of women's health more broadly.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Finnish Dental Society of Apollonia (to MG) and The Research Foundation of Helsinki University Central Hospital (to TS) as well as Brazilian research funding agencies FAPERGS (PqG 1008860, PqG 1008857, ARD11/1893-7, PRONEX 1000274), CAPES (PROCAD 066/2007), CNPq (558289/2008-8 and 302330/2009-7), as well as PROPESQ-UFRGS (to FZ-C).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Baggio G, Corsini A, Floreani A, Giannini S, and Zagonel V. (2013). Gender medicine: A task for the third millennium. Clin Chem Lab Med 51, 713–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendrik C, and Dabrosin C. (2009). Estradiol increases IL-8 secretion of normal human breast tissue and breast cancer in vivo. J Immunol 182, 371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E, Andrews D, Caccamo M, et al. (2006). Ensembl 2006. Nucleic Acids Res 34, D556–D561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti TC, Salomao R, Brunialti M, Braga DP, Borges E, Jr, and Silva ID. (2010). Cytokine and hormonal profile in serum samples of patients undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation: Interleukin-1beta predicts ongoing pregnancy. Hum Reprod 25, 2101–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Liu YL, and Sytwu HK. (2012). Immunologic regulation in pregnancy: From mechanism to therapeutic strategy for immunomodulation. Clin Dev Immunol 2012, 258391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IM, Morrison JJ, Hackett GA, Powell EK, Cawston TE, and Smith SK. (1994). Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases: Serum levels during pregnancy and labor, term and preterm. Obstet Gynecol 83, 532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockle JV, Gopichandran N, Walker JJ, Levene MI, and Orsi NM. (2007). Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in preterm perinatal complications. Reprod Sci 14, 629–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Córdoba B, and Santiago-García J. (2014). Saliva: A fluid of study for OMICS. OMICS 18, 87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S, Mestres J, and Testa B. (2007). In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: Applications to targets and beyond. Br J Pharmacol 152, 21–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre TA, Ducluzeau F, Sneddon TP, Povey S, Bruford EA, and Lush MJ. (2006). The HUGO Gene Nomenclature Database, 2006 updates. Nucleic Acids Res 34, D319–D321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MM. (2012). What do 'omic technologies have to offer periodontal clinical practice in the future? J Periodontal Res 47, 2–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy UK, Könönen E, Pussinen PJ, et al. (2011). Use of host- and bacteria-derived salivary markers in detection of periodontitis: A cumulative approach. Dis Markers 30, 299–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy M. (2012). Pregnancy and periodontium. A clinical, microbiological, and enzymological approach via a longitudinal study, PhD Thesis. (Annales Universitatis Turkuensis D 1047, Painosalama Oy, Turku: ) (http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-5241-0). Last access: June19, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy M, Gürsoy UK, Sorsa T, Pajukanta R, and Könönen E. (2013). High salivary estrogen and risk of developing pregnancy gingivitis. J Periodontol 84, 1281–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy M, Haraldsson G, Hyvönen M, Sorsa T, Pajukanta R, and Könönen E. (2009). Does the frequency of Prevotella intermedia increase during pregnancy? Oral Microbiol Immunol 24, 299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy M, Könönen E, Gürsoy UK, Tervahartiala T, Pajukanta R, and Sorsa T. (2010a). Periodontal status and neutrophilic enzyme levels in gingival crevicular fluid during pregnancy and postpartum. J Periodontol 81, 1790–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy M, Könönen E, Tervahartiala T, Gürsoy UK, Pajukanta R, and Sorsa T. (2010b). Longitudinal study of salivary proteinases during pregnancy and postpartum. J Periodontal Res 45, 496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanemaaijer R, Sorsa T, Konttinen YT, et al. (1997). Matrix metalloproteinase-8 is expressed in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Regulation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and doxycycline. J Biol Chem 272, 31504–31509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson E. (1960). Pregnancy gingivitis. Harefuah 58, 224–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holten-Andersen L, Thaysen-Andersen M, Jensen SB, et al. (2011). Salivary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 localization and glycosylation profile analysis. APMIS 119, 741–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SD, and Bork P. (2005). Medusa: A simple tool for interaction graph analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 4432–4433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide M, and Papapanou PN. (2013). Epidemiology of association between maternal periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes—Systematic review. J Periodontol 84 S181–S194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Sarrel PM, Poole-Wilson PA, and Collins P. (1992). Acute effect of 17 beta-estradiol on rabbit coronary artery contractile responses to endothelin-1. Am J Physiol 263, H271–H275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda N, and Watanabe S. (2001). 17beta-estradiol, progesterone, and dihydrotestosterone suppress the growth of human melanoma by inhibiting interleukin-8 production. J Invest Dermatol 117, 274–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss E, Sewon L, Gorzó I, and Nagy K. (2010). Salivary calcium concentration in relation to periodontal health of female tobacco smokers: A pilot study. Quintessence Int 41, 779–785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousidou OCh, Berdiaki A, Kletsas D, et al. (2008). Estradiol-estrogen receptor: A key interplay of the expression of syndecan-2 and metalloproteinase-9 in breast cancer cells. Mol Oncol 2, 223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, von Mering C, Campillos M, Jensen LJ, and Bork P. (2008). STITCH: Interaction networks of chemicals and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 36, D684–D688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Huang R, Chen L, et al. (2004). Identification of interleukin-8 as estrogen receptor-regulated factor involved in breast cancer invasion and angiogenesis by protein arrays. Int J Cancer 109, 507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth L, Hsieh CC, Wide L, et al. (1999). Maternal pregnancy hormone levels in an area with a high incidence (Boston, USA) and in an area with a low incidence (Shanghai, China) of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 79, 7–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe WL, Jr, and Karban J. (2014). Genetics, genomics and metabolomics: New insights into maternal metabolism during pregnancy. Diabet Med 31, 254–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löe H, and Silness J. (1963). Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand 21, 533–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamalis A, Markopoulou C, Lagou A, and Vrotsos I. (2011). Oestrogen regulates proliferation, osteoblastic differentiation, collagen synthesis and periostin gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells through oestrogen receptor beta. Arch Oral Biol 56, 446–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti A. (1994). Sex steroid hormones and cell dynamics in the periodontium. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 5, 27–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebel D. (2012). Functional importance of estrogen receptors in the periodontium. Swed Dent J 221, 11–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebel D, Jönsson D, Norderyd O, Bratthall G, and Nilsson BO. (2010). Differential regulation of chemokine expression by estrogen in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res 45, 796–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson BO. (2007). Modulation of the inflammatory response by estrogens with focus on the endothelium and its interactions with leukocytes. Inflamm Res 56, 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novella S, Heras M, Hermenegildo C, and Dantas AP. (2012). Effects of estrogen on vascular inflammation: A matter of timing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32, 2035–2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir V. (2013). OMICS 2.0: A practice turn for 21(st) century science and society. OMICS 17,1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polan ML, Daniele A, and Kuo A. (1988). Gonadal steroids modulate human monocyte interleukin-1 (IL-1) activity. Fertil Steril 49, 964–968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polan ML, Loukides J, Nelson P, et al. (1989). Progesterone and estradiol modulate interleukin-1 beta messenger ribonucleic acid levels in cultured human peripheral monocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 69, 1200–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu L, Guan SM, Fu SM, Guo T, Cao M, and Ding Y. (2008). Estrogen modulates cytokine expression in human periodontal ligament cells. J Dent Res 87, 142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsa T, Tjäderhane L, and Salo T. (2004). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in oral diseases. Oral Dis 10, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RH. (2007). The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev 28, 521–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, and Sullivan DA. (2005). Estrogen stimulation of proinflammatory cytokine and matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in human corneal epithelial cells. Cornea 24, 1004–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed F, and Khosla S. (2005). Mechanisms of sex steroid effects on bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328, 688–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tency I, Verstraelen H, Kroes I, et al. (2012). Imbalances between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) in maternal serum during preterm labor. PLoS One 7, e49042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsinti M, Kassi E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. (2009). Functional estrogen receptors alpha and beta are expressed in normal human salivary gland epithelium and apparently mediate immunomodulatory effects. Eur J Oral Sci 117, 498–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshenyuk TG, and Gardner JD. (2010). Estrogen improves TIMP-MMP balance and collagen distribution in volume-overloaded hearts of ovariectomized females. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299, R683–R693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Goldman S, and Shalev E. (2007). The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPS) in the decidua and fetal membranes. Front Biosci 12, 649–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder RL. (1998). Hormones, pregnancy, and autoimmune diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci 840, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Spiers A, Ewan J, Johnson P, Jenkins C, and Carr S. (2009). Effects of high dose oestrogen therapy on circulating inflammatory markers. Maturitas 62, 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidán-Chuliá F, Gelain DP, Kolling EA, et al. (2013a). Major components of energy drinks (caffeine, taurine, and guarana) exert cytotoxic effects on human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells by decreasing reactive oxygen species production. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 791795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidán-Chuliá F, Neves de Oliveira BH, Gursoy M, et al. (2013b). MMP-REDOX/NO interplay in periodontitis and its inhibition with Satureja hortensis L. essential oil. Chem Biodivers 10, 507–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidán-Chuliá F, Rybarczyk-Filho JL, Gursoy M, et al. (2012). Bioinformatical and in vitro approaches to essential oil-induced matrix metalloproteinase inhibition. Pharm Biol 50, 675–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidán-Chuliá F, Rybarczyk-Filho JL, Salmina AB, de Oliveira BH, Noda M, and Moreira JC. (2013c). Exploring the multifactorial nature of autism through computational systems biology: Calcium and the Rho GTPase RAC1 under the spotlight. Neuromolecular Med 15, 364–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidán-Chuliá F, Gursoy M, de Oliveira BH, et al. (2014). Focussed microarray analysis of apoptosis in periodontitis and its potential pharmacological targeting by carvacrol. Arch Oral Biol 59, 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]