Abstract

Diabetes prevention is a public health priority that is dependent upon the reach, effectiveness, and cost of intervention strategies. However, understanding each of these outcomes within the context of randomized controlled trials is problematic. This study uses a unique hybrid design that allows an assessment of reach by providing participants choice between interventions and an assessment of effectiveness and cost using a standard randomized controlled trial (RCT). The trial, which was developed using the RE-AIM framework, will contrast the effects of 3 interventions: (1) a standard care, small group, diabetes prevention education class (SG), (2) the small group intervention plus 12 months of interactive voice response telephone follow-up (SG-IVR), and (3) a DVD version of the small group intervention with the same IVR follow-up (DVD-IVR). Each intervention includes personal action planning with a focus on key elements of the lifestyle intervention from the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Adult patients at risk for diabetes will be randomly assigned to either choice or RCT. Those assigned to choice (n=240) will have the opportunity to choose between SG-IVR and DVD-IVR. Those assigned to RCT group (n=360) will be randomly assigned to SG, SG-IVR, or DVD-IRV. Assessment of primary (weight loss, reach, & cost) and secondary (physical activity, & dietary intake) outcomes will occur at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months. This will be the first diabetes prevention trial that will allow the research team to determine the relationships between reach, effectiveness, and cost of different interventions.

Keywords: Diabetes Prevention, DVD, IVR, Hybrid design, RE-AIM, Weight loss

1. Introduction

The prevention of Type 2 diabetes is a public health priority due to its prevalence, negative influence on health, and lack of a known cure [1]. The results of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) indicated that modest weight loss achieved through diet and exercise was effective in delaying the onset of Type 2 diabetes [2]. Given the potential public health impact of DPP a number of efforts have been made to translate the lifestyle intervention into practice. A recent review reported on 28 effectiveness trials based on the DPP lifestyle intervention or its principals [3]. On average, across healthcare or community setting and whether delivered by health professionals, lay leaders, or interactive technology, these interventions were able to facilitate a similar percent reduction in body weight as the original DPP [3].

While the findings from these trials are promising and certainly speak towards the potential for diabetes prevention activities to be effective in community and clinical practice, there is a paucity of information on other key factors necessary to determine if these interventions can truly be translated into practice [4]. Specifically, Glasgow and colleagues suggested that when planning and evaluating lifestyle interventions, the translation of research evidence into practice will be better informed by assessing information across a number of outcomes represented by the RE-AIM framework [5]. This includes reporting on reach, effectiveness, and maintenance of effects at the individual level and adoption, implementation and maintained delivery at the organizational level. Similarly, Abrams and colleagues proposed that to understand the overall impact of evidence-based strategies, two factors are critical to the overall impact on the target population—reach and effectiveness [6]. Specifically, if an effective intervention cannot reach a significant and representative proportion of the target population it will have limited impact. The evidence that key elements of the DPP lifestyle intervention can be successfully applied in multiple community and clinical settings is extremely promising, but to date there is a lack of literature related to the reach of diabetes prevention strategies beyond simply reporting on the number of participants or a participation rate based on an inconsistent denominator [4]. In fact, the calculation of actual reach is never possible within the traditional RCT designs where participants must consent to being randomized to one of the available conditions. As such, innovative designs that allow researchers to investigate both reach and effectiveness of diabetes prevention programs are needed.

Applications of the RE-AIM framework also recommend understanding the costs of intervention delivery in terms of reach and effectiveness [7]. To date, determining the cost-effectiveness of diabetes prevention has been tied solely to information gleaned from the outcomes of the DPP trial [8–11]. In nearly every case, translational diabetes prevention trials in the United States were adapted to reflect the DPP key elements using a lower frequency of sessions (e.g., 11 to 16 sessions), typically delivered to groups rather than to individuals [12–20]. These adaptations are made as a method to reduce intervention costs, but only three studies reported cost explicitly and those that do have simply reported on the cost of the intervention rather than on cost-effectiveness in achieving outcomes [13, 18, 21]. Studies that determine the relationships between reach, effectiveness and cost of diabetes prevention programs delivered in typical clinical or community settings are needed.

2. Primary Research Goals

The diaBEAT-it! Project used the RE-AIM framework to plan potential interventions that had the potential to: (1) reach a high proportion of patients at risk for type 2 diabetes, (2) effectively support patients to reduce body weight by 5%, (3) be scalable in order to improve potential adoption across healthcare settings, (4) be implemented at a reasonable cost, and (5) lead to weight loss maintenance and be sustained in typical healthcare settings. Based on this five-fold focus we developed two potentially scalable interventions that could, after appropriate testing, be broadly adopted, easily implemented, and sustained in typical healthcare settings. Both interventions are 12 months in duration and include a live call to assist participants in initiating changes and 22 interactive voice response (IVR) follow-up support calls. The interventions differ in the initial patient contact—one is initiated with a small group, in-person session (SG/IVR) and the other is initiated with a DVD (DVD/IVR).

The primary purposes of the project are to determine the reach of each active intervention (i.e., the number, proportion, and representativeness of patients enrolled), the effectiveness of the strategies in supporting patients to lose and maintain a 5% weight loss, and the cost-effectiveness of the interventions in achieving standard weight loss. Secondary purposes include reporting on the adoption rate of family and community medicine clinics and physicians approached to participate and the degree to which the interventions are delivered as intended, as well as determining whether participant preference impacts intervention effectiveness when compared to a control group.

3. Methods

3.1. Design Overview

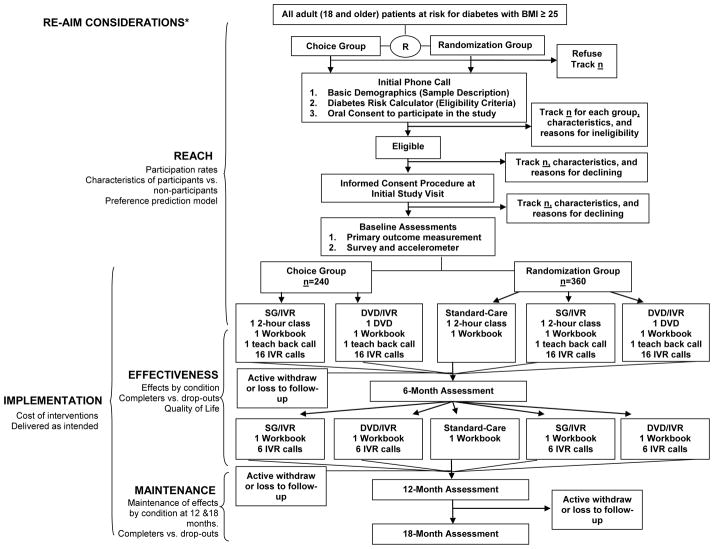

To achieve our study goals we will conduct a pragmatic clinical trial [22–24] that employs a hybrid preference/randomized control trial (RCT) design [25–27] (see Figure 1). Patients at risk for developing diabetes will be randomly assigned to either a Choice group or a Randomization group. Choice group participants (n=240) will have the ability to select which of the two interventions they prefer, while those in the Randomization group (n=360) will be randomly assigned to one of three groups (including a standard care control (SC) consisting of only the diabetes prevention class). This hybrid 2 group preference and 3 group randomized controlled trial design [25–27] allows us to determine the effectiveness of two interventions relative to SC in reducing body weight within the context of a traditional RCT, while still determining the relative reach of SG/IVR and DVD/IVR within the context of the 2 group preference design components. This design maximizes efficiency in testing of new interventions by capitalizing on the strengths of both the RCT and preference designs [25–27]. This study and protocol were approved by the Carilion Clinic Institutional Review Board and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02162901).

Figure 1.

diaBEAT-it Trial: Consort diagram of procedures for the hybrid preference/randomized controlled trial design and RE-AIM considerations

*Adoption is operationalized as the proportion and representativeness of clinics and physicians that agree to refer patients to the study.

3.2. Participant Eligibility and Recruitment

Carilion Clinic serves 18 counties and six cities in Western and Southwestern Virginia and employs nearly 600 physicians across 160 practices. The total patient population (~1 million patients) includes a range of racial and economic diversity. Patients who receive care at the Carilion Clinic Family and Community Medicine Clinics in the greater Roanoke Metropolitan area in southwest Virginia will be invited to participate in this study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria (see table 1 for detailed information) are as broad as possible to improve the likelihood of attracting a representative sample of patients at risk for type 2 diabetes to the study and increase the likelihood that our findings are generalizable and relevant to typical patient populations [22–24]. Initial eligibility will be determined using Carilion Clinic electronic medical records to identify potential participants (i.e., ≥18 years old, BMI of 25 or greater, ICD-9 codes for prediabetes, glucose intolerance, metabolic syndrome, and obesity while excluding those with ICD-9 codes indicating diagnosed diabetes, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease). Finally, all participants will be screened for information necessary to complete the Diabetes Risk Calculator [28] to ensure patients at risk for diabetes are enrolled in the study. The Diabetes Risk Calculator uses 7 items to evaluate diabetes risk including questions related to age, sex, gestational diabetes, family history with diabetes, blood pressure levels, physical activity levels, and current weight and height. Individuals with a score of 5 or higher are considered to be in particularly greater risk and will be the target for recruitment into the current project. Additionally, those who are positively identified as having diabetes will be excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Overview and Research Design

| Sample & Design | Intervention Arms | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

Participants (n=600) Adult primary care patients at risk for diabetes Participant eligibility criteria Inclusion: Age ≥ 18; BMI ≥ 25; and indicates high risk for developing diabetes, based on the Diabetes Risk Test Calculator 1, 2 Exclusion: Type 2 diabetes diagnosis; Pregnant or becomes pregnant during trial; Contraindication to physical activity or weight loss; No access to phone (those with no access to telephone will be included in the denominator of the reach calculation); Does not speak or read English; Indicates DO NOT CONTACT in medical record Hybrid Preference/RCT Design: Preference (n=240) Randomly assigned to choose either SG/IVR or DVD/IVR intervention arm RCT (n=360) Randomly assigned to one of three groups: SC (n=120); SG/IVR (n=120); DVD/IVR (n=120) |

Standard Care (SC) Single 2-hour small group session and workbook targeting key elements of DPP (e.g., action planning for increased PA, improved nutrition, & weight loss; goal setting, barrier Identification and resolution). Small Group (SG)/IVR 2-hour small group session and workbook identical to SC. 1 live counseling call, 22 tailored IVR calls targeting increased PA, improved nutrition, weight loss, problem solving, participant’s action plan, & staying motivated. Offered for 12 months with final six focused on maintenance and relapse prevention based on DPP’s after core program. DVD/IVR DVD replicating SC and workbook. 1 live counseling call, 22 tailored IVR calls identical to those described above in SG/IVR. |

Reach Number Participation rates Representativeness of participants and non-participants Preference prediction model Effectiveness Weight loss Physical activity Dietary behaviors Quality of Life Adoption (setting) Number, proportion, and representativeness of participating clinics Adoption (staff) Number, proportion and representativeness of participating physicians/providers Implementation Intervention Cost Degree to which intervention is delivered as intended Maintenance Intervention effectiveness at 12- and 18-months Outcomes assessed at baseline, 6, 12 & 18 months |

1Heikes, K.E.; Eddy, D.M.; Arondekar, B.; Schlessinger, L. Diabetes Risk Calculator: a simple tool for detecting undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes care. 2008; 31:1040–1045

2High risk is indicated by score ≥ 5 on Diabetes Risk Calculator (or score ≥ 3 for African-American and Hispanic women ages 40 and below)

The Carilion Clinic Family and Community Medicine includes 12 practices in the recruitment area and 237 primary care physicians who provide care for over 150,000 patients that range in demographics from 17 to 49 percent African American and a small Latino population (~3% of all patients). To date, all clinics have agreed to take part in the study with 2 clinics being selected to initiate participation based on the population served (primarily low income or racial minority patients). Both clinics have identified more than 3,000 patients that are potentially eligible for the study with a high proportion of uninsured (33%) and Medicaid eligible patients (22%). After initial patient identification, Carilion Clinic physicians will have an opportunity to review the list of their patients who have been identified as potentially eligible for the study at each data pull. These physicians will be able to request the removal of any patient from the recruitment process. Physicians not willing to participate in the study will have their patients removed from the potential participant list.

After physicians remove patients they do not wish to recruit, the remaining patients will be randomized to either the 3-group RCT design (Randomization Group) or the 2-group preference design (Choice Group) prior to any study contact following a randomization table with a 60/40 split based on the overall enrollment goals for each group (i.e. RCT: 360, Choice: 240). Patients randomized to the Choice group will receive an initial letter from their physician that provides general information regarding the study, a description of SG/IVR and DVD/IVR, and an invitation to choose which program they would like to join. Patients assigned to the Randomization group will receive a similar letter that describes the RCT. Enclosed with both letters will be an “opt-out” postcard that patients can return if they do not wish to be contacted further about the study. All patients who do not return the opt-out postcard will receive an outreach recruitment call. During this call, a research assistant will reiterate the key points of the letter, answer any questions, determine initial eligibility, assess whether patient wishes to participate, and if so, obtain full contact information and schedule a baseline study visit. Patients with disconnected numbers or no telephone number on file will be excluded from the trial, but will be included in the documentation of the proportional reach of the study. Informed consent procedures and baseline assessments will be completed at the time of the first study visit. Once all baseline assessments are completed participants will either be randomized to one of the RCT groups or given the opportunity to choose which program they would like to take part in. All participants who choose or are randomized to the DVD/IVR program will receive the DVD to take home following the baseline data collection. A DVD player will be provided at no cost to those participants without one. Those in the SC and SG/IVR will have their SG date scheduled within a month of the baseline visit. Finally, all participants will receive $25.00 for each assessment point (i.e. baseline, 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month) completed as a thank you for their time.

3.3. Sample Size Calculation

We have powered our study to detect statistically significant body weight changes at 6 months and 12 months in SG/IVR and DVD/IVR when compared with the SC control group within the RCT design. We used weight change as the primary outcome variable and, based on our previous studies [29–31], we projected an average weight loss of 5.4 lbs in the IVR intervention group and 3.1 lbs of weight loss in the control group over 6 months of intervention, which is slightly lower than the magnitude of weight loss found in previous research studies employing more intensive approaches [14, 15, 18]. To determine the potential of weight regain to influence the power of the study we projected the potential weight loss maintenance at both 12 and 18 months using averages from two studies that include similar intervention strategies to maintain weight loss [32, 33] (i.e., 89% of weight loss maintained at 12 months for intervention and 68% for control). Thus at 12 months we projected 4.8lbs lost in the intervention groups and 2.1lbs lost in the control group. Using these differences in weight and standard deviations while assuming a correlation of .5 between repeated measures a sample size of 78 participants per group is needed to achieve 90% study power and a 0.01 significance level.

3.4. Interventions

3.4.1. Standard-Care

Carilion Clinic currently offers a 2-hour small group session that was designed to help patients develop a personal action plan for diabetes prevention [29–31]. This session is available to any Carilion Clinic patient who has been diagnosed with pre-diabetes or has blood glucose concentration between 100–125 mg/dL (i.e., IFG), and has been offered for the past 4 years. All participants randomized to the standard-care/control group (SC) will be offered participation in a small group session. Details of the content of this intervention have been fully described elsewhere [29–31]. Participants in the small group sessions are encouraged to set a goal of losing 10% of their current weight over 12 months and to set a goal to be physically active for 60 minutes, 5 days per week. The content of the personal action plan was developed to address the same functioning principles that provided the basis for the DPP lifestyle sessions [34], including listing motivational reasons to avoid diabetes, personal goals for weight management, physical activity, and healthful eating, identifying barriers, strategies to overcome barriers, and upholding accountability for these goals through a commitment to enlist friends and/or family members in the change process [29, 30]. A program outline and content were developed to facilitate discussion among the participants, prompting group conversation, allowing exchange of ideas around social cues for living a healthy lifestyle, ways to eat healthfully when dining out, the use of stimulus controls, and ways to get back on track when one slips out of a healthy routine [29, 30]. Additionally, instructors (Certified Diabetes Educators and/or Registered Dietitians) present detailed information on current recommended levels of physical activity and healthful food choices involving portion size, eating regular meals, and a well-balanced diet based on the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Instructors also provide a workbook covering all 22 session topics (table 2) and self-monitoring tools to be used throughout the program designed to track weight loss, physical activity, and dietary behaviors. Finally, care will be taken to make sure SC participants are not scheduled for the same sessions as SG/IVR participants to avoid contact across groups.

Table 2.

Intervention schedule and details

| Time | Mode | Topic | Session Content | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 | DVD or SG Class | Introduction to program | Understand T2DM and steps to help prevent it Benefits of PA, healthy eating (HE) and weight loss PA types and guidelines MyPlate strategies and guidelines |

Complete Diabetes Risk Test Calculate current PA and HE patterns Develop personal action plans Identify motivation, barriers & strategies to meet goals |

| Week 1 | Live Call | Teach Back & Teach to Goal | Review benefits of weight loss, physical activity, and healthy eating. Revisit personal action plan. For those who missed SG class- complete action planning. Teach back and teach to goal techniques used throughout. | Teach Back & Teach to Goal Assess WT, PA & FV intake Personal action plans |

| CORE SESSIONS BEGIN | ||||

| Week 2 | IVR #1 | Move Those Muscles | Review benefits & types of PA Discuss PA safety Develop a PA plan for the upcoming week Begin tracking PA & eating behaviors1 |

Assess WT, PA & FV intake Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 3 | IVR #2 | Being Active: A Way of Life | Strategies to be more active each day Develop a PA plan for upcoming week addressing the F.I.T.T principles (frequency, intensity, time & type of PA) |

Assess WT, PA & FV intake & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 4 | IVR #3 | Healthy Eating With MyPlate | Review ChooseMyPlate How to read Nutrition Labels Simple switches to healthy eating “Rate My Plate” homework activity |

Assess WT, PA & FV intake, & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 5 | IVR #4 | Be A Fat Detective | Understanding different types of fat Identifying hidden & added fats Nutrition label reading activity Begin tracking intake of added fats |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & eating behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 6 | IVR #5 | Be A Sugar Detective | Understand added sugars & empty calories Finding added sugars in nutrition labels Begin tracking intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) |

Assess WT, PA, FV & Fat intake & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 7 | IVR #6 | Tip the Calorie Balance | Understanding calorie balance, energy requirements & portion control Strategies for lowering calorie intake Begin tracking calorie intake (KCALS) |

Assess WT, PA, FV & Fat intake & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 8 | IVR #7 | Take Charge of What’s Around You | Understand healthy and unhealthy food & activity cues Develop plan to handle unhealthy cues |

Assess WT, PA, FV, Fat, SSB & KCALS intake & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 9 | IVR #8 | Problem Solving | Learn 5 steps to problem solving Action planning to resolve common PA & diet-related problem |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 11 | IVR #9 | 4 Keys to Healthy Eating Out | Common challenges and tips to eating healthy in restaurants Asking for what you want when eating out |

Assess WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 13 | IVR #10 | Talk Back to Negative Thoughts | Motivational thinking to keep away from the negative spiral Ways to break negative thoughts |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 15 | IVR #11 | Slippery Slope of Lifestyle Change | Review progress thus far How to recover from common slips Action planning to recover from slips |

Assess WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 17 | IVR #12 | Jump Start Your Activity Plan | Overcoming lack of motivation Revisit F.I.T.T. principles Practicing the “talk-test” to measure intensity during PA |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 19 | IVR #13 | Make Social Cues Work For You | How to create social support & identify a friend/family member to support healthy lifestyles Planning for social events |

Assess WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 21 | IVR #14 | Shaking Your Salt Habit | Heart health & importance of reducing salt intake Practice reading food labels to identify hidden salts Strategies and tips to eat less salt |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 23 | IVR #15 | You Can Manage Stress | Identifying where stress begins Tips to handle stress Action planning to handle common personal stressors |

Assess WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Feedback on WT change Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 25 | IVR #16 | Ways to Stay Motivated | Review progress & achievements over the past 6-months Tips: 8 steps to stay motivated during post-core Identify personal motivators & healthy ways to reward success |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| POST-CORE SESSIONS BEGIN | ||||

| Week 29 | IVR #17 | Mindful Eating | Introduction to Post-Core Discuss what mindful eating means & how it benefits weight loss Practice ways to eat slowly & mindfully at home |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 33 | IVR #18 | Stress & Time Management | Revisit triggers for stress & ways to handle them Discuss strategies to better manage time and stress Develop a schedule and plan to help manage time for more PA |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 37 | IVR #19 | Standing Up For Your Health | Discuss sedentary behavior & importance of standing instead of sitting Track the amount of time spent sitting over 1 week & reflect on it Identify ways to lower sitting time |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 41 | IVR #20 | More Volume, Fewer Calories | Introduce concept of volumetrics & the difference between “calorie-dense” and “nutrient-dense” foods Discuss role, benefits & importance of eating more fiber |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 45 | IVR #21 | Strengthen Your Exercise Program | Discuss components of a well-rounded physical fitness program & the benefits of muscle strengthening activities Review muscle strengthening guidelines |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal Homework assignment |

| Week 49 | IVR #22 | Looking Back & Looking Forward | Emphasize lifestyle changes involves an on-going self-review process. Reflection on self-awareness, personal responsibility and willingness to continue with behavior changes |

Assess & provide feedback on WT, PA & dietary behaviors & homework Action Planning: goal setting, identifying and overcoming barriers Session topic & teach to goal |

1Participants will track PA & Dietary Behaviors on a weekly basis in a Food & Activity Log

3.4.2. Small Group & Interactive Voice Response (SG/IVR)

This intervention was developed to help participants initiate weight loss via the promotion of a healthful diet and regular physical activity, and maintain their behavior changes. Its primary objective is to help participants achieve the goal of losing 10% of their current weight in 12 months and be physically active for 60 minutes, 5 days per week. The 12-month intervention starts with the attendance of a small group session as described above. In addition to the small group session, the program was designed to be longer and include more supportive calls than our previous studies [31]. The content topics will continue to focus on achieving a balanced diet that reduces fat and caloric intake plus adding regular exercise as intervention components to enhance initial weight loss and prevent weight regain [35]. Our program will continue to include DPP lifestyle intervention key elements of problem-solving, goal setting, and feedback as well as direct participants to examine their home, neighborhood, social, and work environments to elicit changes which support a more healthful lifestyle. We also found the 5 A’s model to assist participants in setting physical activity and healthful eating goals necessary for weight loss and maintenance useful in designing the intervention content [36]. This model includes Assessing behaviors, providing Advice on possible changes, collaboratively Agreeing on a plan of action, Assisting participants in the identification of strategies to overcome personal barriers to behavior change, and Arranging for follow-up [36]. The intent is to facilitate the participants’ sense of control and expectancy of being able to cope successfully with challenging situations.

Because a large amount of intervention content is presented to the participants during the class session, we will use a health literacy focused strategy to increase the likelihood that participants understand materials related to the course objectives (e.g., weight loss, nutrition, and physical activity recommendations). Participants will receive a follow-up telephone call approximately one week after the SG session that will be based on the principles of teach to goal and teach-back strategies. These strategies allow participants to describe key intervention concepts using their own words [37, 38] and to complete additional rounds of education until the participant demonstrates he/she has a firm understanding of the information [39–41]. This call will be delivered by a Certified Diabetes Educator or a research assistant. The caller will ask questions based on the session content assessing each participant’s level of knowledge and understanding of core focus points (i.e., MyPlate guidelines, types and length of physical activity); as well as answer any questions or concerns. Participants will also provide the personal action plan goals they set during the session. The action plan goals will be recorded in our participant database system and used as a means of assessment in the IVR calls.

Approximately one week following the teach-back call the participants will begin receiving IVR support calls. There will be a total of 22 IVR calls over a period of 12 months, with 16 calls being part of the core program, and 6 being part of the after core/maintenance program (see table 2). The core 16 IVR calls will be completed over a 6-month period, beginning with 8 weekly calls followed by 8 biweekly calls. The frequency of calls was chosen based on our experiences during one of our preliminary studies [42]. Each IVR call will provide content related to each 16-session topic covered during the DPP lifestyle intervention (table 2), and lasts between 15 to 30 minutes [34]. Additionally, during each IVR call participants will provide information on current weight, physical activities, and dietary behavior. This information will be compared to participants’ goals for these areas (e.g., weight reduction, minutes of moderate intensity PA daily; servings of fruits and vegetables) and will be used to provide feedback on success in subsequent IVR calls. Feedback will be based on the progress being made towards the accomplishment of each goal as set by the participants (e.g., weight goals, minutes of PA goals; servings of fruits and vegetables goals). Again, we apply the health literacy strategy of teach-back and teach to goal in that at the completion of each call participants are asked to provide responses to questions about the objectives discussed on each call. To avoid the potential of aggravating participants by asking the same questions again during the same automated call if the participant answers incorrectly, we included two novel strategies. First, all responses, whether or not the participant responded correctly, reinforces the objective of the call. Second, for participants who answer a call incorrectly, they will receive a second opportunity to complete the questions at the beginning of the subsequent IVR call.

After completion of the 16-call core program, the after core/maintenance program will be initiated. Following DPP’s after core program [34], we have developed our maintenance program to ensure sustained contact with participants over the course of the 12 months of the program. We have developed six monthly calls to ensure this continued contact in a manner similar to the phone contacts employed during DPP’s after core program [34]. As suggested by DPP’s after core program, our maintenance program also takes an active, problem-solving approach in every call (similar to our core program), allowing participants to expect the same structure every time and providing opportunities for automated teach-back (see table 2 for additional call content information). The only exception is the first IVR maintenance call, which also includes an introduction to the maintenance program and revisits participants’ action plans using the 5 A’s approach. At the end of each call, participants will receive information regarding relapse prevention and keeping on track.

3.4.3. DVD & Interactive Voice Response (DVD/IVR)

We developed a DVD and an accompanying workbook to cover the same content areas as the SG session while guiding participants through developing their own personal action plans targeting weight loss via increased physical activity and a balanced, well-rounded diet. The DVD/IVR condition has been designed with the intent of capitalizing on the strengths of both technologies (DVD & IVR) by providing an ideal combination of convenience, which is hypothesized to improve our reach, and cost, while still delivering an intensive program and maintaining its significant clinical effects. The DVD itself, in addition to a short introduction describes how the DVD works, introduces the workbook, and provides a summary. The DVD is divided in the following segments that align with the SG sessions: 1) What is pre-diabetes? 2) What are the risk factors for diabetes? 3) Developing your diaBEAT-it action plan, 4) Goal setting for physical activity & healthy eating, 5) putting together a toolbox of resources, and 6) making a commitment to change. The DVD’s main segment lasts about 60 minutes with a number of stop places to encourage participants to stand-up and take a break before going back to the DVD. In addition, we have added segments related to nutrition and physical activity which can be viewed for free online by the CDC (www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity.html) and Eat Smart, Move More NC (www.myeatsmartmovemore.com/aislebyaisle.html). Key concepts are illustrated by high-quality graphics and animations, and video segments depict models from different cultures engaging in a variety of health behaviors. A goal-setting and problem-solving approach similar to that in the SG session has been utilized. Toward the end of each content segment, viewers will be instructed to pause the DVD and complete an action plan page in the accompanying workbook.

The teach-back call and IVR components of this intervention are the same as described in the SG/IVR intervention and are designed to address and reinforce the messages delivered in the DVD and the content of the participants’ action plans. The teach-back call will occur approximately one week after the participant is provided with the DVD. Participants will be asked if they completed the DVD or not to both determine fidelity and allow for the participant to do so before the teach-back call is completed. If the DVD has not been completed, the participant will be asked to complete the DVD and a follow-up teach-back call will be scheduled one week later. If the DVD is not completed after 2 follow-up calls, we will use the teach-back call to deliver key messages from the DVD and complete a 5 A’s process to develop a personal action plan for the participant. Those participants who have completed the DVD will receive the same teach-back call as the SG/IVR group, including the collection of action plan information.

3.5. Measures

Table 1 illustrates the primary and secondary outcome measures and a general timeline for data collection. All baseline measures will be collected after participants are randomly assigned to the preference group or the RCT group, but prior to RCT group randomization or participant choice for those in the preference group.

Body Weight

The primary outcome of this study is body weight that will be assessed using the calibrated Health-O-Meter 2101KL digital stand-on scale (www.homscales.com). A research assistant will administer the weighing to ensure accuracy with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes.

Assessment of Cost

We will estimate total intervention costs, incremental costs associated with the intervention groups relative to the SC condition, costs per participant, and marginal costs per incremental percent weight reduction. Resource use associated with the intervention will be valued at competitive market rates. All costs will be estimated and evaluated in constant dollars using the Prospective Payment System Input Price Index [30]. The following major resource categories will be examined: (1) costs of identifying and recruiting participants, including items associated with the Carilion Clinic staff, (2) direct intervention labor costs calculated to represent hourly wages including fringe benefits of delivery staff, (3) personnel recruitment and training costs, (4) postage costs of mailed material, (5) DVD and IVR development, production, and maintenance costs, and (6) material and supply costs (e.g., printed material, supplies for printers). During all phases of development and implementation we will document what was done, who did it, how long it took to complete, and what non-human resources were required. Care will be taken to accurately separate research-based costs (e.g., costs of follow-up assessments and research surveys) from clinical replication or implementation costs [43]. In addition, based on the RE-AIM framework we have included an assessment of quality of life that will also be used to determine comparative cost effectiveness across conditions [44].

3.5.1. Reach

Reach will be assessed according to RE-AIM guidelines by a) the participation rate among eligible patients and b) the representativeness of participants [45]. The denominator of eligible participants over the study recruitment period (e.g. ICD-9 codes) will be determined by accessing Carilion Clinic’s electronic medical records. For representativeness, we will compare the demographic and health characteristics of patients who participate to characteristics of eligible patients who receive care in the greater Roanoke metropolitan area at Carilion Clinic. We will determine reach and representativeness of participants in the overall trial, those randomly assigned to RCT versus preference, and when comparing those who chose SG/IVR versus DVD/IVR. We will also assess the reasons given for declining participation.

3.5.2. Physical Activity Behaviors

The activPAL™ will be used to objectively assess physical activity [46]. The activPAL from PAL Technologies is an accelerometer for quantifying free-living, sedentary, upright and ambulatory activities which has been used in over 300 studies (www.paltechnologies.com). The activPAL™ has demonstrated strong validity and reliability when compared to known activities and other brands of accelerometers [47, 48]. Each participant will wear an activPAL accelerometer for 7 days at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months and will maintain a daily PA diary as to improve the validity of the assessment [47].

3.5.3. Dietary Behaviors

The design of the nutrition component of the intervention is hypothesized to impact three primary areas of consumption—fruits and vegetables, dietary fat intake, and sugar sweetened beverage consumption. As such, the Fruit-Vegetable-Fiber Screener and the Block Dietary Fat Screener were selected as assessment tools for the eating behaviors. These brief dietary screeners were developed using the top sources of fat, fruits and vegetables in the US diet, according to national survey data [49]. The Fruit-Vegetable-Fiber Screener is a self-administered 10-item survey, which provides information on usual intake of fruits and vegetables (servings/day), vitamin C (mg), magnesium (mg), potassium (mg), and dietary fiber (grams). The Fat Screener is a self-administered one-page screener which includes 17 items, and provides information on usual intake of total fat (grams), saturated fat (grams), percent of energy from fat, and dietary cholesterol (grams). Finally, though it was not a specific area of goal setting in the original DPP lifestyle intervention, due to the building evidence on the role of sugar sweetened beverages in average caloric intake, we included the assessment of these beverages using a validated measure that is sensitive to changes in beverage intake [50].

3.5.4. Adoption and Implementation

Our study is not intended to determine the relative adoptability of one intervention over another and, as such, we will focus our assessment of adoption on the proportion and representativeness of the clinics and physicians that agree to participate in the program delivery. We anticipate 100% adoption at the clinic level due to our partnership with Carilion Clinic Family and Community Medicine, but expect that there may be some physicians who do not have the time or interest necessary to reach out to participants with letters of invitation. We will compare the characteristics of the participating physicians to the characteristics available on primary care doctors that work in Carilion Clinic related to years of experience, gender, and location. The project is also intended to be an initial test of the interventions and no organizational level maintenance of delivery is planned.

We will assess the degree to which the intervention is delivered as intended to provide data on the implementation dimension of the RE-AIM framework. Although the use of interactive technologies may enhance fidelity, there is still a need to monitor the timing, content, and completion of each automated step in the protocol. We have developed a detailed manual that includes all the strategies to be implemented and approximate dates for completion of each intervention component. The manual will serve as a source to develop checklists for evaluation of treatment fidelity and the degree to which the interventions are implemented as intended. In addition, IVR call records will be used to create reports of participant completion. For the purposes of our analyses, a call will be considered completed once the voice files for the lesson of the week have been played. This way we will ensure that our participants complete their regular assessments, receive feedback on their progress, update their action plans when appropriate, and receive the lesson content. Our comprehensive evaluation of treatment fidelity [51] will determine whether: (a) the treatment was delivered as intended, (b) the participants received the intervention delivery as intended, and (c) the participants applied the skills learned from the intervention in their everyday lives [51]. Finally, DVD/IVR participants will be queried about the use of the DVD during their initial IVR calls.

3.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive, parametric, and non-parametric statistical methods will be used to compare continuous and categorical variables among the intervention conditions at baseline. If any baseline differences exist between groups, demographic characteristics will be used as covariates in our models. We will also compare the primary and secondary outcome variables at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months. Data will be examined for the presence of outliers, violations of normality (for continuous variables) and missing data. Major violations of normality will be corrected with an appropriate transformation procedure. We will also employ multiple imputation methods to account for missing data [52]. We will employ Intention to treat analysis to include all participants randomized to the three conditions for all comparisons and treatment effects analysis.

3.6.1. Primary Aim Analysis

The first primary aim will be to determine the effectiveness of two diabetes prevention programs, SG session plus IVR and DVD plus IVR, in significantly reducing objectively assessed body weight in the short term (6 months) among adults with pre-diabetes when compared to a standard-care control group. To simultaneously account for individual effects regardless of the condition, we will employ a linear mixed effect model to a multi-treatment framework [53] for the treatment effect analysis [54]. This model will allow us control error non-independence, heteroskedasticity caused by individual heterogeneity, and potential covariates needed to be controlled for achieving good randomization effects. The goal is to make more accurate inferences about the treatment effect of main interest: the effect of SG/IVR and DVD/IVR in reducing body weight over 6 months when compared to SC group. In its simplest form, the model generally can be shown as: . This model depicts the body weight of an individual i at time t and group j. The time t = 0, 6, 12, 18. The group j = 1 (Standard-care), 2 (SG/IVR) and 3 (DVD/IVR). The treatment group indicator, dji will be 1 if the individual is randomized to group j and 0 otherwise. The individual patient’s characteristics will be represented by Xkit and they are allowed to change over time as well. The last three terms in the model make up the error structure of the model. The individual specific unobserved heterogeneity that is time-invariant is represented by μi and the time specific unobserved heterogeneity that is individual-invariant is represented by λt. The idiosyncratic error term is vit. A compound symmetry error structure will be used. For this primary aim, we are interested in only t = 0 and 6. If the treatments have no effect beyond the control group, we would expect to find that β1 = β2 = β3. Moreover, given multiple treatment framework, we can address many interesting hypotheses. Let , we can evaluate treatments based on pair wise comparisons (after joint estimation): we can compare each interventions (i.e., group 2 and group 3) with the control (group 1) by examining ξ2 − ξ1 = 0 and ξ3 − ξ1 = 0; we can also compare the two intervention groups by examining ξ2 − ξ3 = 0. Note that the above hypothesis testing is different from the standard tests of coefficients in that our concern is primarily with the estimated impacts on weight not on the coefficient estimates. These methods will also serve for the analysis of our secondary outcomes. First, we will investigate changes in physical activity and dietary behavior assessed by validated behavioral measures. Second, we will investigate the effectiveness of two diabetes prevention programs in enhancing longer term weight loss (12 months) and maintenance of weight loss (18 months) when compared to a standard-care control group.

3.6.2. Reach and Representativeness

The second primary aim will be to determine the reach and representativeness of participants who select SG/IVR when compared to DVD/IVR. Data collected in the preference design will be used to accomplish this aim. Prediction models will be estimated utilizing individual level data (e.g., demographics) and program level data (e.g., program characteristics of the two interventions). Nonlinear multivariate models (probit and logit) will be used to predict program reach. These models will answer the question of on average what probability a patient of a specific profile will prefer one program to another. The results will help to identify potential barriers and disincentives that negatively affect program reach and further inform recruitment strategies.

3.6.3. Cost-effectiveness Analysis

The third primary aim will be to determine the cost and cost-effectiveness of each intervention arm based on cost per 10% reduction in body weight. We will model the costs and cost per 10% reduction in body weight (note, costs per 5% or other % weight loss will also be modeled). We acknowledge that the recommendations put forth by the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine commissioned by the USDHHS [55] suggest that cost-effectiveness analyses should be conducted using a reference case, viewed from a societal perspective, and incorporate methods that capture benefits, harms, and costs to all. However, given the scope of this project, it would be difficult to fully capture social costs and benefits, and we are especially interested in the perspective from which clinics and patients would evaluate the results and costs to them of such a program. Thus we will conduct this analysis primarily from the perspective of the potential adopting clinics or payers such as patients and/or insurance companies. Resource use associated with the intervention will be valued at competitive market rates. Analyses will evaluate the cost of delivering the interventions and will estimate total intervention costs, costs/participant, and marginal costs/participant. We will conduct a range of sensitivity analyses using Monte Carlo simulations to alter discount rates, changes in adherence/characteristics of the participants to conduct a full cost effectiveness analysis.

3.6.5. Preference Design Analysis

The final aim will be to determine if participant preference impacts intervention effectiveness when compared to the control group. This aim will be accomplished through comparing the estimated effectiveness across the two groups (i.e., RCT and Preference). If the preference towards programs has significant impact on the program effectiveness, we would expect the preference group participants to have extra motivation to adhere to the program they choose and achieve a relatively larger weight loss when compared to the similar program participants in the RCT group. Parametric and nonparametric tests will be employed to perform the statistical comparison of the weight loss of the same program participants across the two groups. Furthermore, we will employ econometric selection models (e.g., Heckman two-stage selection model, Double-Hurdle model, and two-part model) to evaluate potential bias brought to the treatment effect estimators when participants in the program are not randomly assigned, but instead they make their own decision of which program to participate. Through modeling the participation stage decision-making, the second-stage program effect estimation will be able to control for this preference impact and result in consistent program impact estimation. The preference impact on the program effectiveness can be tested statistically. For example, the Heckman two-stage model involves a first step of Probit model that estimate the participation decision and then generate an inverse Mills ratio (IMR) term that captures the selection bias; then this IMR will be entered in the second step weight loss equation as an extra regressor to control for the selection bias. The coefficient of the IMR in the second-step can be tested to see whether it is significantly different from zero. If it is significant, it confirms the existence of the preference impact on the program effectiveness.

4. Discussion

Diabetes prevention programs face several challenges, including reaching those at most risk for developing type 2 diabetes, delivering effective interventions in a sustainable format, and providing individual participants with the right mixture of intensity, personalization, and flexibility. In previous work we found that only 8% of the eligible clinical population participated in a single session diabetes prevention class [29]. This is challenging because effective interventions are usually intensive [12–20, 56–62]. Furthermore, intensive interventions are often expensive and offer little flexibility in when sessions are offered, often resulting in low participation rates [4]. This generally makes program adoption and sustainability within a healthcare setting unfeasible. Interactive technology may provide a solution to these challenges by offering lifestyle behavior change and weight loss information to high-risk individuals at times and places convenient to them [47, 63–67].

Regarding diabetes self-management, Glasgow and associates [68] demonstrated that in-person small group sessions promoting physical activity, healthful eating, and weight control could successfully be replicated using a DVD-based format. Similarly, Kramer and colleagues [69] delivered an adaptation of the DPP lifestyle intervention via DVD with remote participant support. Their results suggested that a diabetes prevention program delivered via DVD with remote support may be an effective alternative [69]. Furthermore, our previous work indicated that 83% of patients at risk for diabetes would prefer the DVD over a class [42]. Consequently, an interactive DVD targeting the promotion of physical activity, healthy eating, and weight loss could be a viable way to deliver diabetes prevention strategies. Given that well over 88% of all households own a DVD player, a DVD-based intervention could reach most US households [70]; in fact, in one of our recent studies less than 10% of a low income sample of patients at risk for diabetes were without a DVD player [42]. Further, once the initial production costs are realized, DVDs are fairly inexpensive to reproduce and are always available for additional booster sessions. DVDs can also store large quantities of high quality sound and video graphics information allowing for further tailoring. Finally, using DVD formats to deliver content similar to that being offered in small group sessions in other diabetes prevention interventions avoids costly training and issues with treatment fidelity [18, 71]. Thus a DVD format could be used to deliver strategies that demonstrated efficacy within the DPP.

In addition to the DVD technology, interactive voice response (IVR) systems that provide automated telephone health education messages may be a practical method for providing nutrition, physical activity, and weight loss information for individuals at high risk for developing diabetes. IVR has been used in a number of healthcare contexts and has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing physical activity and healthy eating [72–78]. IVR has been successfully used for chronic disease self-management [75, 76], physical activity promotion [74, 77], nutrition support [73], and smoking cessation [78]. Furthermore, in a review of controlled clinical studies, Krishna and associates determined that patients found IVR care acceptable and helpful [79].In one of our recent studies, over 76% of participants perceived the IVR system easy to use and about 75% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that IVR messages either did, or could, help them prevent diabetes [31]. Additionally, reviews of the literature indicate that IVR is a cost-effective method of maintaining diabetes self-management [72, 79]. IVR technology can deliver frequent intervention components while allowing for participants to indicate the time and location of intervention receipt. Adding the IVR technology to a DVD-based intervention can therefore deliver large amounts of DPP content at frequencies, times and places that are most convenient to individual participants. The result could be diabetes prevention interventions that have broad reach and be sustained for a low cost.

The diaBEAT-it! project includes a number of novel innovations. First, it was designed with a focus on the RE-AIM framework to increase the likelihood that, if successful, these interventions could be scaled-up for easy adoption, implementation, and sustainability in typical health care settings. Second, while the use of interactive technology to address weight loss is not new, diaBEAT-it! will be the first program to combine the use of two interactive technologies (DVD and IVR), capitalizing on the strengths of each to target initial behavior change and weight loss and subsequent maintenance of these changes. This is a significant departure from previous translational diabetes prevention trials that relied primarily on multiple, frequent, small group sessions that are associated with high personnel costs. While previous research has evaluated the effectiveness of the use of IVR-based interventions in other domains [72–78] and the use of DVD and human telephone calls within a diabetes prevention program [69], no diabetes prevention program has combined the use of these two technologies as part of the same intervention. Furthermore, both interventions are scalable and have potentially low delivery costs once they are developed. Most existing diabetes prevention programs are geographically restricted in their ability to reach participants; those who live outside the delivery area or are unable to attend at scheduled times cannot participate. DiaBEAT-it! has the potential to bridge these gaps by allowing individuals with a DVD player and telephone (over 90% of low income patients at risk for diabetes in our target population [42]) to participate in a diabetes prevention program at a convenient location and time.

Third, this novel hybrid preference/experimental design will provide the unique opportunity to understand the potential reach of two diabetes prevention programs and provide decision-makers with valuable information regarding patients’ preferences, while still evaluating the overall effectiveness through a randomized controlled trial. Our design builds on the strengths of both preference and RCT designs while minimizing some of their weaknesses. Preference designs are typically thought to enhance external validity of studies, while being susceptible to many confounding factors [25, 80]. For instance, the characteristics of those who choose one option may differ from the characteristics of those who choose the second option in significant and meaningful ways that may make casual inferences very difficult [25, 80]. Conversely, in RCT designs investigators are able to eliminate rival hypotheses in highly controlled conditions, that allow casual inference and maximizes internal while sacrificing external validity [81]. However, when the controlled experiment methods cannot be reproduced in real world situations, the results often cannot be replicated [82]. This is particularly problematic in health behavior modification programs, where many efficacious interventions fail to reproduce the same results under real world circumstances [83, 84]. Consequently, diaBEAT-it! was developed to capitalize on the strengths of both designs, and thus enhance both internal and external validity to demonstrate both efficacy and effectiveness. Specifically, our design will allow us to determine the proportional reach of two diabetes prevention programs, an outcome that is never possible in traditional RCT designs where participants must consent to being randomly assigned to one program or another. While a few studies have examined patient choice or preference in drug therapy [82, 85], clinical interventions [86, 87], and health education interventions [88], none to our knowledge have investigated the effects of randomization vs. choice on the effectiveness or reach of a diabetes prevention program.

Fourth, we utilized a systems approach [89] following Roger’s [90] model of innovation-decision process to develop and adapt our program so that it has a greater chance to be adopted and sustained by healthcare providers. Beyond paying close attention to organizational structure and needs, systems approaches engage the practice community in active decision making when developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions with the ultimate goal of participatory dissemination [89]. This novel approach to program development was effective in developing an introductory diabetes prevention class [30], which was sustained within an integrated healthcare organization after the formal trial was complete and has been adopted as the standard care for Carilion Clinic. The diaBEAT-it! project takes a similar systems approach [89] with a healthcare partner with the ultimate goal of having a low cost, sustainable intervention that reaches a large proportion of patients with pre-diabetes and has robust effects on weight loss. This system based approach to program development, therefore, allows for collaborations with clinical partners throughout the design, implementation, and evaluation so that the program fits with their regular clinical practices, leading to greater chances of adoption and sustainability [89].

Finally, the combined assessment of reach and effectiveness with an in-depth cost-effectiveness analysis will provide a deeper understanding of the potential of the interventions to be sustained and disseminated beyond the context of our current healthcare partner. This approach to design and analysis will provide important information not often available in traditional RCT studies. More specifically, we will provide information regarding a) the effectiveness of two programs, b) the cost of two programs, c) patient’s program preference, d) a valid assessment of program reach, and e) marginal cost per 10% reduction in body weight. DiaBEAT-it! will be the first diabetes prevention program to provide decision makers with information that will allow comparisons of the cost of adopting/offering each program versus its effectiveness, while understanding the preferences of potential participants.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R18DK091811-01A1 (Almeida, PI).

We would like to acknowledge the entire Virginia Tech and Carilion Clinic research team who has been instrumental in the development and implementation of the diaBEAT-it trial, including Kate Jones, Vicki Baker, Rochelle Brown, Cynthia Karlson, Yu Sun, Qian-Qian Qin, Blake Krippendorf, and Peter Moreau. We also wish to thank the InterVision Media team (Steve Christiansen, Tom Jacobs, Lauren Brown, Toan Tran, and Joe Merkel) for their countless hours of assistance and endless support.

Abbreviations

- RE-AIM

reach effectiveness adoption implementation maintenance

- PA

physical activity

Footnotes

The content is solely of the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Fabio A. Almeida, Email: falmeida@v.edu.

Kimberlee A. Pardo, Email: skim13@vt.edu.

Richard W. Seidel, Email: rwseidel@carilionclinic.org.

Brenda M. Davy, Email: bdavy@vt.edu.

Wen You, Email: wenyou@vt.edu.

Sarah S. Wall, Email: sarahsw@vt.edu.

Erin Smith, Email: erinsmith@vt.edu.

Mark H. Greenawald, Email: mhgreenawald@carilionclinic.org.

Paul A. Estabrooks, Email: estabrkp@vt.edu.

Bibliography & References Cited

- 1.Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Obesity. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health affairs. 2012;31:67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laws RA, St George AB, Rychetnik L, Bauman AE. Diabetes prevention research: a systematic review of external validity in lifestyle interventions. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;43:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American journal of public health. 1999;89:1322–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams DB, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer W. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: a combined stepped-care and matching model. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18:290–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02895291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estabrooks PA, Allen KC. Updating, employing, and adapting: a commentary on What does it mean to “employ” the RE-AIM model. Evaluation & the health professions. 2013;36:67–72. doi: 10.1177/0163278712460546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackermann RT, Edelstein SL, Narayan KM, Zhang P, Engelgau MM, Herman WH, et al. Changes in health state utilities with changes in body mass in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity. 2009;17:2176–81. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackermann RT, Marrero DG, Hicks KA, Hoerger TJ, Sorensen S, Zhang P, et al. An evaluation of cost sharing to finance a diet and physical activity intervention to prevent diabetes. Diabetes care. 2006;29:1237–41. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eddy DM, Schlessinger L, Kahn R. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of strategies for managing people at high risk for diabetes. Annals of internal medicine. 2005;143:251–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, Hicks K, Sorensen S, Zhang P, et al. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Annals of internal medicine. 2005;142:323–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008;35:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amundson HA, Butcher MK, Gohdes D, Hall TO, Harwell TS, Helgerson SD, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into practice in the general community: findings from the Montana Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Prevention Program. The Diabetes educator. 2009;35:209–10. 13–4, 16–20. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333269. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boltri JM, Davis-Smith YM, Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Okosun IS, Cornelius ME. Diabetes prevention in a faith-based setting: results of translational research. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. 2008;14:29–32. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000303410.66485.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer MK, Miller RG, Venditti EM, Orchard TJ. Group lifestyle intervention for diabetes prevention in those with metabolic syndrome in primary care practice. Diabetes. 2006;55:A517-A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride PE, Einerson JA, Grant H, Sargent C, Underbakke G, Vitcenda M, et al. Putting the Diabetes Prevention Program into practice: a program for weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction for patients with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes mellitus. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2008;12:745S–9S. doi: 10.1007/BF03028624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merriam PA, Tellez TL, Rosal MC, Olendzki BC, Ma Y, Pagoto SL, et al. Methodology of a diabetes prevention translational research project utilizing a community-academic partnership for implementation in an underserved Latino community. BMC medical research methodology. 2009;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagoto SL, Kantor L, Bodenlos JS, Gitkind M, Ma Y. Translating the diabetes prevention program into a hospital-based weight loss program. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27:S91–8. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seidel MC, Powell RO, Zgibor JC, Siminerio LM, Piatt GA. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into an urban medically underserved community: a nonrandomized prospective intervention study. Diabetes care. 2008;31:684–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittemore R, Melkus G, Wagner J, Dziura J, Northrup V, Grey M. Translating the diabetes prevention program to primary care: a pilot study. Nursing research. 2009;58:2–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, Miller RG, Brooks MM, Burke LE, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: a comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;37:505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasgow RE, Magid DJ, Beck A, Ritzwoller D, Estabrooks PA. Practical clinical trials for translating research to practice: design and measurement recommendations. Medical care. 2005;43:551–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163645.41407.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, Treweek S, Furberg CD, Altman DG, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2009;180:E47–57. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1624–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley C. Designing medical and educational intervention studies. A review of some alternatives to conventional randomized controlled trials. Diabetes care. 1993;16:509–18. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rucker G. A two-stage trial design for testing treatment, self-selection and treatment preference effects. Statistics in medicine. 1989;8:477–85. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennberg JE, Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Mulley A. Outcomes research, PORTs, and health care reform. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;703:52–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heikes KE, Eddy DM, Arondekar B, Schlessinger L. Diabetes Risk Calculator: a simple tool for detecting undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes care. 2008;31:1040–5. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almeida FA, Shetterly S, Smith-Ray RL, Estabrooks PA. Reach and effectiveness of a weight loss intervention in patients with prediabetes in Colorado. Preventing chronic disease. 2010;7:A103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Ray RL, Almeida FA, Bajaj J, Foland S, Gilson M, Heikkinen S, et al. Translating efficacious behavioral principles for diabetes prevention into practice. Health promotion practice. 2009;10:58–66. doi: 10.1177/1524839906293397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estabrooks PA, Smith-Ray RL. Piloting a behavioral intervention delivered through interactive voice response telephone messages to promote weight loss in a pre-diabetic population. Patient education and counseling. 2008;72:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, Gold EC. Effect of internet support on the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Obesity research. 2004;12:320–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, et al. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168:2347–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes care. 2002;25:2165–71. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;82:222S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical activity promotion through primary care. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2913–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss BD Association AM. Health literacy and patient safety: Help patients understand: manual for clinicians. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkman ND, Davis TC, McCormack L. Health literacy: what is it? Journal of health communication. 2010;15 (Suppl 2):9–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker DW, Dewalt DA, Schillinger D, Hawk V, Ruo B, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. The effect of progressive, reinforcing telephone education and counseling versus brief educational intervention on knowledge, self-care behaviors and heart failure symptoms. Journal of cardiac failure. 2011;17:789–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.06.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Baker DW, Schillinger D, Ruo B, et al. Comparison of a one-time educational intervention to a teach-to-goal educational intervention for self-management of heart failure: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC health services research. 2009;9:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, Chanmugam A, Hill P, Rand CS, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172:980–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seidel RW, Pardo KA, Estabrooks PA, You W, Wall SS, Davy BM, et al. Beginning a patient-centered approach in the design of a diabetes prevention program. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014;11:2003–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110202003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meenan RT, Stevens VJ, Hornbrook MC, La Chance PA, Glasgow RE, Hollis JF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hospital-based smoking cessation intervention. Medical care. 1998;36:670–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richardson J, Khan M, Iezzi A, Sinha K, Mihalopoulos C, Herrman H, et al. The AQoL-8D (PsyQoL) MAU Instrument: Overview September 2009. Centre for Health Economics, Monash University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health education research. 2006;21:688–94. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dowd KP, Harrington DM, Bourke AK, Nelson J, Donnelly AE. The measurement of sedentary patterns and behaviors using the activPAL Professional physical activity monitor. Physiological measurement. 2012;33:1887–99. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/11/1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King AC, Friedman R, Marcus B, Castro C, Forsyth L, Napolitano M, et al. Harnessing motivational forces in the promotion of physical activity: the Community Health Advice by Telephone (CHAT) project. Health education research. 2002;17:627–36. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welk GJ, Blair SN, Wood K, Jones S, Thompson RW. A comparative evaluation of three accelerometry-based physical activity monitors. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2000;32:S489–97. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Block G, Gillespie C, Rosenbaum EH, Jenson C. A rapid food screener to assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. American journal of preventive medicine. 2000;18:284–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedrick VE, Comber DL, Ferguson KE, Estabrooks PA, Savla J, Dietrich AM, et al. A rapid beverage intake questionnaire can detect changes in beverage intake. Eating behaviors. 2013;14:90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]