Abstract

The incidence of ureteric obstruction after kidney transplantation is 3–12.4%, and the most common cause is ureteric stenosis. The standard treatment remains open surgical revision, but this is associated with significant morbidity and potential complications. By contrast, endourological approaches such as balloon dilatation of the ureter, ureterotomy or long-term ureteric stenting are minimally invasive treatment alternatives. Here we discuss the available minimally invasive treatment options to treat transplant ureteric strictures, with an emphasis on long-term stenting. Using an example patient, we describe the use of a long-term new-generation ureteric metal stent to treat a transplant ureter where a mesh wire stent had been placed 5 years previously. The mesh wire stent was heavily encrusted throughout, overgrown by urothelium and impossible to remove. Because the patient had several previous surgeries, we first considered endourological solutions. After re-canalising the ureter and mesh wire stent by a minimally invasive procedure, we inserted a Memokath® (PNN Medical, Kvistgaard, Denmark) through the embedded mesh wire stent. This illustrates a novel method for resolving the currently rare but existing problem of ureteric mesh wire stents becoming dysfunctional over time, and for treating complex transplant ureteric strictures.

Keywords: Ureteric stricture, Kidney transplant, Stent, Metal, Memokath

Introduction

The incidence of ureteric obstruction after kidney transplantation is 3–12.4% [1], and the most common cause is ureteric stenosis. The standard treatment remains open revision and ureteroneocystostomy or pyelo-ureterostomy [2], both invasive approaches with significant morbidity and postoperative complications. Also, it might be technically difficult in patients who have had many previous surgical interventions. By contrast, endourological approaches can offer minimally invasive treatment options [3]. Balloon dilatation of the ureter, ureterotomy or long-term ureteric stenting have all been used successfully, albeit with each having its particular advantages and disadvantages.

For ureteric stenting, permanent mesh wire stents have been used previously, with varying success. The particular problem with these stents is that they are overgrown by host tissue and thus very difficult to remove later, if at all [4,5].

Here we discuss minimally invasive treatment options to treat transplant ureteric strictures, with an emphasis on long-term stenting. Using the example of a patient we describe the use of a long-term new-generation ureteric metal stent to treat a transplant ureter where a mesh wire stent had been placed 5 years previously. The mesh wire stent was heavily encrusted throughout, overgrown by urothelium and impossible to remove. Because the patient had undergone several previous surgical procedures we first considered endourological solutions. After re-canalising the ureter and mesh wire stent by a minimally invasive procedure we inserted a Memokath® 051 (PNN Medical, Kvistgaard, Denmark) through the embedded mesh wire stent. This illustrates a novel method of dealing with the currently rare but existing problem of ureteric mesh wire stents becoming dysfunctional over time, and not only in transplanted ureters.

Minimally invasive endourological treatment options

The least invasive endourological therapy for ureteric strictures after kidney transplantation is balloon dilatation. This can be done by the antegrade or retrograde route and is often accompanied by placing a temporary stent. The short-term success rates are 50–65%, but the long-term results are rather disappointing [6–8]. Treatment in the first 10 weeks after transplantation can be successful, whereas it is not recommended thereafter [9].

Slightly more invasive are incisive approaches such as endoureterotomy which can be done with electrocautery, laser or the Acucise® cutting balloon catheter (Applied Medical Resources Corp., Laguna Hills, CA, USA). All have been used successfully, but to date the evidence is not convincing as too few cases are reported [10–14].

If such surgical treatment has failed or is impossible, for example because the stricture is too long, long-term ureteric stenting remains as an option. JJ stents are perhaps the least invasive and most time-tested stents [15]. However, JJ stents are associated with complications such as irritative symptoms, encrustation, and, more importantly, infections, which occur significantly more frequently in these immune-suppressed patients if the stent is indwelling for >30 days [16,17]. Also, JJ stents need to be exchanged at least every 3–6 months, which is most inconvenient for the patients and can be technically challenging under the distorted anatomical conditions after transplantation.

To overcome these problems, self-expanding metallic mesh wire stents were used previously. They were first introduced for treating biliary strictures and cardiovascular stenosis. For treating stenosis of the ureter, but also in the prostate and urethra, they showed good short-term but disappointing long-term results, with significant complications. There are only a few reports of their use in transplant ureteric stenosis [18]. Their main disadvantage was the rapid urothelial overgrowth, with consecutive ingrowth of hyperplastic urothelium and granulation tissue. This frequently led to complete obstruction and made removal of the device often impossible [4,5].

Another more recent stenting option for ureters is the full-length, double-pigtail, metallic Resonance® ureteric stent (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). However, it must be exchanged at least once a year. For malignant extrinsic ureteric obstruction the results have been encouraging, but for benign strictures they are still inconclusive [19]. Its use has not yet been reported in ureteric stenosis of transplant kidneys.

Nitinol metallic stents (Sinuflex®, Optimed, Ettlingen, Germany) have been successfully used in the treatment of transplant ureteric stenosis, with a long-term patency of 75% after 4 years (16 patients) [20]. Another nitinol ureteric stent, the Memokath® 051, is a thermo-expandable, nickel-titanium alloy ureteric stent. With its spiral structure, the stent can adapt to the curve of the ureter, avoiding outward pressure, thus preventing ischaemic lesions and preserving peristalsis. The tight coils prevent urothelial ingrowth, which facilitates easy removal if needed, and its titanium component makes it resistant to encrustation and corrosion. Several studies have shown that the Memokath 051 not only has a successful long-term clinical outcome, but also is a cost-effective minimally invasive management option for both benign and malignant ureteric strictures [21].

A small series of its use in transplanted kidneys was published in 2005 [22]. Of four stents, two remained patent during a follow-up of 21 months, one was infected and replaced after 14 months, and one migrated after only 10 days in situ.

In cases where patency of the transplanted ureter cannot be achieved but major reconstructive surgery (i.e., ileum interposition) is not an option, an extra-anatomical subcutaneous stent (Detour®, Coloplast, Minneapolis, USA) can be a minimally invasive option. This subcutaneous bypass graft is based on a PTFE-silicone tube. The proximal end is placed into the transplant kidney like a nephrostomy, and the tube itself is tunnelled under the skin and sutured into the bladder, acting as an artificial ureter. In a small series of eight patients, seven showed good graft function with no evidence of obstruction or infection. Recurrent infection occurred in two recipients, leading to one graft loss [23]. However, the Detour stent remains a salvage procedure whenever other surgical or endourological approaches are not indicated or have failed [24,25].

The use of a metal stent in an unusual case

A 27-year-old white man with a transplanted kidney and prune-belly syndrome presented with acute onset of left loin pain, nausea, vomiting and fever of 38 °C. His medical history showed a complex urological background, with renal failure and subsequently a live-related kidney transplant at the age of 21 years. Six months later he developed a uretero-vesical anastomotic stricture of the transplanted ureter. To avoid further open surgery the stricture was treated by anterograde radiological insertion of a self-expanding mesh-stent. A year after that, an atonic bladder necessitated a vesicostomy (Boari flap). Because of ischaemic necrosis and retraction this needed to be replaced shortly thereafter with a modified ileal conduit vesicostomy (bowel to bladder). During this intervention, the previously placed Wallstent was found to have migrated about 2.5 cm into the urinary bladder, and heavy urothelial overgrowth made its repositioning or removal impossible. After trimming this overhanging part, the mesh-stent then remained patent for another 5.5 years, but recurrent UTIs necessitated several hospital admissions, with administration of intravenous antibiotics.

On admission, physical examination revealed a tender left iliac fossa. Blood analysis results showed raised infection parameters, with a white cell count of 17.2 × 109 L−1 and a C-reactive protein level of 214 mg/L. Kidney function was impaired, with a GFR of 23 mL/min, a serum creatinine level of 291 μmol/L and blood urea of 18.1 mmol/L. Two weeks earlier, on a routine check, the patient’s kidney function had still been normal, with a GFR of 77 mL/min, a serum creatinine level of 104 μmol/L and blood urea of 8.6 mmol/L, respectively.

Ultrasonography showed severe hydronephrosis of the transplanted kidney and a plain abdominal film showed pronounced calcifications adherent to the proximal end and lumen of the stent, as well as a stone of ≈15 × 10 mm at the distal end of the mesh stent that protruded into the bladder (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Encrusted mesh wire stent with a stone at the bladder end and encrustations in the lumen and the renal end in a transplant ureter.

As an initial emergency treatment the transplanted kidney was drained with a percutaneous nephrostomy, and under antibiotic treatment the patient’s kidney function and inflammatory values quickly returned to normal, indicating good kidney function and recovery potential. When the situation had stabilized, the patient was taken to theatre for a combined antegrade percutaneous and retrograde transurethral procedure, while supine. Percutaneous access to the transplant kidney was gained through the previously placed nephrostomy tube. After dilatation of the tract and insertion of the nephroscope, the stone on the upper end of the mesh stent, and the heavily encrusted lumen, were cleared by electrohydraulic intracorporeal lithotripsy. The stone attached to the bladder side of the mesh stent was removed transurethrally in the same fashion. The now freed stent (Fig. 2) was completely overgrown by urothelium, making its removal impossible.

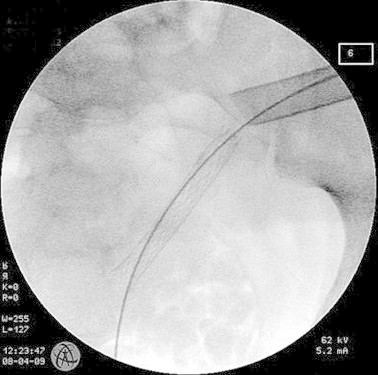

Figure 2.

“Through and trough wire” in the now encrustations-free mesh wire stent following percutaneous nephroscopy.

Therefore a 100-mm long single-expansion Memokath 051 ureteric stent was inserted, using a technique described previously [26], and positioned across the stricture through the 60 mm long mesh stent. Its expandable upper end was placed in the renal pelvis with its distal end protruding ≈20 mm into the bladder.

Recovery after surgery was unremarkable, with a good urinary output from the conduit. Ultrasonography showed persistent resolution of the hydronephrosis. The renal function remained normal, so that the patient could be discharged 2 days later after removing the nephrostomy tube. At the most recent follow-up consultation 27 months after this intervention, the patient was clinically well with no UTIs, and had normal renal function. The GFR had improved to 81 mL/min, the serum creatinine level to 99 μmol/L (normal range <110 μmol/L) and blood urea to 7.2 mmol/L. A follow-up abdominal plain film showed the position of the Memokath 051 inside the mesh wire stent, with no signs of re-encrustation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Follow-up X-ray after 27 months showing the position of the Memokath 051® inside the mesh wire stent without any signs of re-encrustation.

Discussion

Endourology offers minimally invasive treatment options with fewer side-effects and less patient morbidity than with open surgery [3]. This is particularly interesting in unfit patients at high surgical risk, or where open revision is considered technically difficult or has previously failed.

Ureteric balloon dilatation [9,13] and the Acucise cutting balloon catheter [14] can be regarded as truly minimally invasive treatment options, but could not be used in the present case as an overgrown mesh stent was in place within the ureteric wall. The same is true for the slightly more invasive semi-rigid or flexible ureteroscopy for electro- or laser-ureterotomy [10,11]. In general, these procedures can become very challenging through the extra-anatomical access to and the passage through the transplanted ureter. New developments in flexible ureteroscopy have helped to make these procedures more feasible [27].

Long-term ureteric stenting with conventional JJ stents can be considered as the least invasive option [15]. However, apart from necessitating frequent stent changes with their own associated morbidity, it would have exposed our immune-suppressed patient to the risk of recurrent UTI, which could potentially affect graft survival [16,17].

In our department we are familiar with the thermo-expandable, nickel-titanium alloy Memokath 051 stent. Its first use was reported in 1996 [28], and its first use in transplanted kidneys was reported in 2005 [22]. This stent does not need to be changed, has shown a good long-term success rate, with no complications like encrustation or epithelial in-growth, and is cost-effective in the long run compared with JJ stents, with their need for frequent exchange [21].

As mentioned above, mesh wire stents when used previously became overgrown by ureteric tissue and were often impossible to remove when encrusted and blocked [4,5]. This particular problem in the patient’s transplanted and mesh-stented ureter was overcome by ‘stenting the stented ureter’. Of course, such an unusual approach without comparable published evidence demands a thorough follow-up. However, should re-encrustation of the Memokath occur, it can be relatively easily exchanged, in contrast to a mesh wire stent. There was initial concern about possible electrostatic interaction between the two metal stents. We had extensive discussions with the engineering department of the manufacturer, and concluded that complications arising from such interactions would be extremely unlikely.

References

- 1.Dinckan A., Tekin A., Turkyilmaz S., Kocak H., Gurkan A., Erdogan O. Early and late urological complications corrected surgically following renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2007;20:702–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00500.x. [Epub 2007 May 19] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hétet J.F., Rigaud J., Leveau E., Le Normand L., Glémain P., Bouchot O. Therapeutic management of ureteric strictures in renal transplantation. Prog Urol. 2005;15:472–479. [discussion 479-80] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchholz N., El Howairis M., Bach C., Moraitis K., Masood J. From stone cutting to Hi-technology methods: the changing face of stone surgery. Arab J Urol. 2011;9(1):25–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hekimoglu B., Men S., Pinar A., Ozmen E., Soylu S.O., Conkbayir I. Urothelial hyperplasia complicating use of metal stents in malignant ureteral obstruction. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:675–6781. doi: 10.1007/BF00187672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollak J.S., Rosenblatt M.M., Egglin T.K., Dickey K.W., Glickman M. Treatment of ureteral obstructions with the Wallstent endoprosthesis: preliminary results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)72833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachar G.N., Mor E., Bartal G., Atar E., Goldberg N., Belenky A. Percutaneous balloon dilatation for the treatment of early and late ureteral strictures after renal transplantation: long-term follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:335–338. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromwich E., Coles S., Atchley J., Fairley I., Brown J.L., Keoghane S.R. A 4-year review of balloon dilation of ureteral strictures in renal allografts. J Endourol. 2000;20:1060–1061. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juaneda B., Alcaraz A., Bujons A., Guirado L., Díaz J.M., Martí J. Endourological management is better in early-onset ureteral stenosis in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3825–3827. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabenalt R., Winter C., Potthoff S.A., Eisenberger C.F., Grabitz K., Albers P. Retrograde balloon dilatation > 10 weeks after renal transplantation for transplant ureter stenosis – our experience and review of the literature. Arab J Urol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2011.06.014. [Epub ahead of print]. Available from: http://www.ajuweb.com/article/PIIS2090598X11000349/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gdor Y., Gabr A.H., Faerber G.J., Wolf J.S., Jr Holmium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser endoureterotomy for the treatment of transplant kidney ureteral strictures. Transplantation. 2008;85:1318–13121. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816c7f19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhayani S.B., Landman J., Slotoroff C., Figenshau R.S. Transplant ureter stricture: Acucise endoureterotomy and balloon dilation are effective. J Endourol. 2003;17:19–22. doi: 10.1089/089277903321196733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seseke F., Heuser M., Zöller G., Plothe K.D., Ringert R.H. Treatment of iatrogenic postoperative ureteral strictures with Acucise endoureterotomy. Eur Urol. 2002;42:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giessing M. Transplant ureter stricture following renal transplantation: surgical options. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Z., Li X., Chen L., Zeng G., Yuan J., Chen W. Endoscopic incision for obstruction of vesico-ureteric anastomosis in transplanted kidneys. BJU Int. 2008;102:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueiredo A.J., Parada B.A., Cunha M.F., Mota A.J., Furtado A.J. Ureteral complications: analysis of risk factors in 1000 renal transplants. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1087–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavakoli A., Surange R.S., Pearson R.C., Parrott N.R., Augustine T., Riad H.N. Impact of stents on urological complications and health care expenditure in renal transplant recipients: results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2007;177:2260–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson C.H., Bhatti A.A., Rix D.A., Manas D.M. Routine intraoperative ureteric stenting for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19(4):CD004925. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004925.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantasdemir M., Kantarci F., Numan F., Mihmanli I., Kalender B. Renal transplant ureteral stenosis: treatment by self-expanding metallic stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:85–87. doi: 10.1007/s00270-002-1962-5. [Epub 2002 Dec 20] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liatsikos E., Kallidonis P., Kyriazis I., Constantinidis C., Hendlin K., Stolzenburg J.U., Karnabatidis D., Siablis D. Ureteral obstruction: is the full metallic double-pigtail stent the way to go? Eur Urol. 2010;57:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.004. [Epub 2009 Feb 10] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgos F.J., Bueno G., Gonzalez R., Vazquez J.J., Diez-Nicolás V., Marcen R. Endourologic implants to treat complex ureteral stenosis after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2427–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staios D., Shergill I., Thwaini A., Junaid I., Buchholz N.P. The Memokath stent. Expert Rev Med Dev. 2007;4:99–101. doi: 10.1586/17434440.4.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyvat F., Aytekin C., Colak T., Firat A., Karakayali H., Haberal M. Memokath metallic stent in the treatment of transplant kidney ureter stenosis or occlusion. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:326–330. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azhar R.A., Hassanain M., Aljiffry M., Aldousari S., Cabrera T., Andonian S. Successful salvage of kidney allografts threatened by ureteral stricture using pyelovesical bypass. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1414–1419. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andonian S., Zorn K.C., Paraskevas S., Anidjar M. Artificial ureters in renal transplantation. Urology. 2005;66:1109. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giessing M., Schnorr D., Loening S.A. Artificial ureteral replacement following kidney transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2006:578–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papatsoris A.G., Buchholz N. A novel thermo-expandable ureteral metal stent for the minimally invasive management of ureteral strictures. J Endourol. 2010;24:48791. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papatsoris A., Kachrilas S., El Howairis M., Masood J., Buchholz N. Novel technologies in flexible ureterorenoscopy. Arab J Urol. 2011;9(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni R.P., Bellamy E.A. A new thermo-expandable shape-memory nickel-titanium alloy stent for the management of ureteric strictures. BJU Int. 1999;83:755–759. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]