Abstract

Objective

Our goals were to study the propagation models in a situation of persistent temporal epileptic seizures with varying degrees of bitemporal excitability and to analyze which propagation models were found at times of high temporal excitability and which occurred with lower levels of excitability.

Methods

A patient with super-refractory status arising from the temporal lobes was studied daily using video-electroencephalography (VEEG), with a large number of electroclinical seizures recorded. The analysis focused on the method and type of seizure propagation and classified them either according to the propagation models described in the literature or as undetermined.

Results

Video-EEG monitoring was carried out daily for 310 days. A total of 990 electroclinical seizures were recorded; 135 seizures were recorded during the first week, and 523 were recorded in the first month. From the beginning, the interictal recording showed independent discharges over both temporal lobes. The seizures showed independent onset in both temporal lobes. During periods of the highest number of seizures, certain models of propagation begin to predominate through switch of lateralization, temporal asynchrony, early remote propagation, total contralateral propagation, seizures with nonlocalized onset, or models that are difficult to classify. Conversely, when the condition was brought relatively under control, we observed fewer propagation models with predominantly simple patterns: only hemispheric propagation or graduated sequential propagation with a few nonlateralized onset seizures.

Conclusions

Upon analyzing the seizures, we found that the propagation models vary as the status evolved, with the change reflecting the degree of excitability in the mesial temporal–limbic network at a given time. In clinical practice, these changes in propagation models are more likely to be observed in temporal status that extends over time and with an onset of the seizures in both temporal lobes.

Significance

The analysis of the propagation models may provide information about the excitability of the mesial temporal–limbic network.

Keywords: Propagation models, Temporal lobe seizures, Super-refractory status, Scalp ictal EEG, VEEG monitoring in ICU

Highlights

-

•

Studies with ictal scalp electroencephalography (ISE) have identified different propagation models.

-

•

Propagation models change, probably related to the excitability at different times of the mesial temporal–limbic network.

-

•

During periods of poor seizure control, complex propagation models predominate.

1. Introduction

Epileptic discharges in patients with mesial temporal epilepsy (MTE) exhibit highly dispersed propagation times from their origin in the temporal lobe until they arrive at the contralateral mesial region [1]. This is probably reflecting different degrees of temporal excitability, due in part to the different propagation models that can be observed [2–6].

Studies with ictal scalp electroencephalography (ISE) have identified different propagation models, and it has been suggested that there is a relationship between temporal excitability and the response to medical or surgical treatments. The different propagation models are as follows: switch of lateralization and temporal asynchrony [7,8]; only temporal propagation [9]; early remote propagation [10]; ipsilateral hemispheric propagation [11]; graduated, sequential propagation; and total contralateral propagation [11]. It has also been demonstrated that there is a close correlation between the features of the interictal recordings in patients with MTE and the type of propagation observed in the ictal scalp recordings [7,12]. It has observed that independent bitemporal discharges are apparently a marker of bitemporal hyperexcitability, and the way in which the epileptic discharge propagates is also a marker of low or high temporal excitability [11]. Patients with independent bitemporal interictal discharges generally present combinations of nonhabitual or complex propagation models (e.g., switch of lateralization with temporal asynchrony) [7,8], while patients with unilateral discharges generally present one or two propagation models, without the combination of complex models [12]. Nonlateralized onset seizures predominate among patients with independent bitemporal discharges and also presuppose high temporal excitability [13,10].

One aspect to consider is the area of the brain involved in the propagation; in general, the more limited the area of ictal propagation, the less excitable the MTE. This has been corroborated in intracerebral EEG studies, which show that more limited onset and more restricted propagation cases have a better postsurgery response [14,15]. The conclusion can be reached through ISE: ictal discharges that propagate only to the ipsilateral temporal lobe (the mesial group in Chassoux et al. [9]) or that propagate only to the ipsilateral hemisphere (group 1 in Napolitano and Orriols [11]) have low unitemporal excitability and better results with surgery or medical treatment. Conversely, complex patterns of propagation involve more extensive areas of one or both cerebral hemispheres, sometimes almost simultaneously, and are less responsive to medical or surgical treatments [8,14]. However, it has not been described whether the propagation patterns remain stable over time or if, when an underlying disorder intensifies (possibly greater alteration in the mesial temporal limbic network), the simple propagation pattern may coexist with or even be replaced by complex propagation patterns.

We studied a patient with a recent bilateral mesial temporal lesion associated with prolonged temporal lobe status that was refractory to different treatments. We analyzed many of the patient's seizures and how they evolved over time using prolonged video-electroencephalography (VEEG) monitoring, especially examining the propagation models observed.

The purpose of the study was to answer the following questions:

-

1.

Can it really be held that some propagation models are of low excitability and others are of high temporal excitability?

-

2.

What happens with propagation patterns when the seizures increase and persist over time?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient data

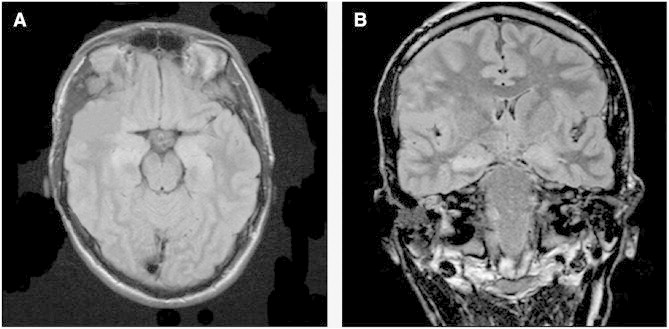

The patient is a 23-year-old male with no previous medical history who, four days prior to being admitted to our hospital, began to suffer persistent headaches accompanied with fever and followed by generalized convulsive seizures; the seizures recurred several times in the following 48 h. Treatment began with intravenous (IV) phenytoin, valproic acid IV, and then a continuous infusion of midazolam. As the convulsive seizures persisted, the patient was transferred to the ICU. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study was normal; screening was done for infectious agents in CSF and blood, both of which were negative. Empirical treatment with acyclovir was then begun, with no change observed in the patient's clinical condition. An initial magnetic nuclear resonance (MNR) study with T2, T1, and FLAIR sequences showed a slight hyperintensity at the bilateral mesial temporal level with a slight thalamic hyperintensity; subsequent tests showed heightened bilateral mesial hyperintensity with the thalamic hyperintensity disappearing (Fig. 1). Magnetic nuclear resonance imaging one to seven months afterward showed disappearance of the mesial hyperintensity but revealed cortical atrophy, especially in the bilateral temporal areas. Serological screening for systemic autoimmune diseases was negative, including ANA, anti-dsDNA, complement (C3/C4), antiphospholipid antibodies, ANCA, and Sjögren's antibodies. Increased antithyroglobulin antibodies were found with normal peroxidase antibodies. Testing for autoantibodies targeting VGKC-complex GAD and onconeural antigens (e.g., Hu Abs, Ma2 Abs, CV2/CRMP5 Abs) was negative (Mayo Clinic Dept. of Lab Med & Pathology). A whole-body computed tomography scan revealed no occult malignancy.

Fig. 1.

MRI FLAIR sequence (A: axial view, B: coronal view) on Day 6 demonstrating bilateral medial temporal lobe hyperintensity.

A suggested diagnosis was seronegative autoimmune limbic encephalitis [16], and the patient was first given methylprednisolone and then immunoglobulins (two cycles). When no response was obtained, a dose of rituximab was given, but this treatment could not be continued because of the presence of a fever and a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis.

The patient remained in the ICU for nine months with super-refractory status as defined by Shorvon and Ferlisi [17], requiring the use, at times, of a combination of midazolam IV, propofol IV, and thiopental IV. After two months of very frequent daily seizures, they were brought under control with thiopental, the use of which maintained EEG burst suppression, but with the reappearance of partial or generalized seizures on several occasions when reduction of the dosage was attempted; increased doses of thiopental were thus required. It was decided to do five cycles of daily plasmapheresis, but it was impossible to completely suspend the use of thiopental because of the reappearance of focal and secondary generalized seizures. Finally, one week after successfully halting the use of thiopental, the patient woke up, looked up when talked to, and was able to connect with family members and to follow simple commands. He has since suffered occasional focal seizures with secondary generalization, usually induced by stimuli, so it may, in the future, be possible to continue his treatment in an intermediate care unit.

2.2. Video-EEG monitoring in ICU

2.2.1. Recording of seizures

The seizures were recorded daily with VEEG in the ICU using a 64-channel NicVue 2.6 Nicolet system (Nicolet, Madison, WI). The recordings were not continuous, lasting from 12 to 17 h per day (starting at approximately 3:00 p.m. and ending at approximately 8:00 a.m. the following day). The international 10–20 electrode system was used without additional electrodes. The data were digitalized at 200 Hz using 1-Hz low-frequency and 70-Hz high-frequency filters. Other types of filters were occasionally used for better analysis of some seizures. We used primarily longitudinal and transversal bipolar montages to analyze the seizures. All of the recordings were analyzed visually (C.N.), and the electroclinical seizures were identified using the criteria described by Young et al. [18].

2.2.2. Analysis of the seizures

Each of the patient's seizures was analyzed according to the criteria described by Steinhoff et al. [7], identifying:

-

1.

Onset: activity other than basal and interictal that persisted for at least 3 s and showed a pattern of seizure development;

-

2.

Localization: classified as regionalized, lateralized, bilateral lateralized, or nonlateralized [7]; and

-

3.Propagation method: analyzed in each electroclinical seizure, assigning it to one of the following models:

-

a.Only ipsilateral temporal [9],

-

b.Only ipsilateral hemispheric [11],

-

c.Graduated and sequential [11],

-

d.Early remote [10],

-

e.Total contralateral [11],

-

f.With switch of lateralization [7],

-

g.With temporal asynchrony [7],

-

h.Nonlateralized bilateral [7], and

-

i.Nonclassifiable in any of the above categories.

-

a.

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics

Video-EEG monitoring was carried out daily for 310 days. A total of 990 electroclinical seizures were recorded, many of which had no clinical expression or were manifested in temporary rises in blood pressure, tachycardia, or, less frequently, in clonic peribuccal movements or clonic movements involving the extremities. On the first day of ICU monitoring (the 6th day of neurological symptoms), five seizures were recorded, and the seizures increased significantly over the days that followed: 135 seizures were recorded during the first week, and 523 were recorded in the first month, and by the end of the second month, 672 electroclinical seizures had been recorded.

3.2. Interictal and ictal EEG characteristics

From the beginning, the interictal recordings showed independent discharges over both temporal lobes. During the first month of recordings, the seizures showed independent onset in both temporal lobes, sometimes alternating from one side to the other. After the first month, when an attempt was made to stop administering thiopental, the seizures reappeared but started only in the right temporal lobe. During other attempts to stop thiopental, the seizures reappeared with mostly right temporal onset, with some independent seizures with left temporal lobe onset.

The basal EEG pattern changed as the seizures increased, and the pharmacological treatments became more aggressive. Frequently noted was a paroxysm-suppression pattern with asymmetrical bilateral sharp waves or spikes over one hemisphere or the other, or, alternately, periodic bilateral epileptic discharges, either spontaneous or induced by stimuli as described by Hirsch et al. [19].

An analysis of the onset of the electrical seizures showed that, in a single session, the seizure onset was sometimes very focal, involving only two electrodes with rhythmic sharp waves (phase opposition) that increased and evolved, while at other times, the seizures had a much more extensive onset, involving an entire temporal lobe or hemisphere with discharges of periodic spikes that later evolved. Especially during the first month, both types of onset would repeat for long periods of time, frequently showing the same type of propagation in a high number of seizures that originated independently in both temporal lobes.

3.3. Analysis of the propagation patterns

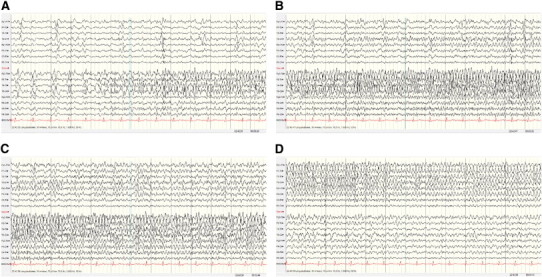

On Day 1 of video-EEG recording in the ICU (Fig. 2), five electroclinical seizures were recorded, with two propagation models identified: a) graduated and sequential and b) switch of lateralization. The onset of the seizures was sometimes in the right temporal lobe and at other times in the left, all with switch of lateralization.

Fig. 2.

Recording from Day 1: five seizures, independent onset in the right and left temporal lobes. Two propagation models (see text). EEG: right temporal onset with graduated, sequential propagation plus switch of lateralization. (A–C) Without interruption, (D) 84 s after onset.

On Day 4, 23 seizures were recorded with four different propagation models, always with either right or left independent temporal onset. The following propagation models were recognized: a) graduated and sequential, b) graduated and sequential with switch of lateralization, c) early remote plus switch of lateralization, and d) temporal or hemispheric regionalized onset, plus total contralateral propagation, plus switch of lateralization.

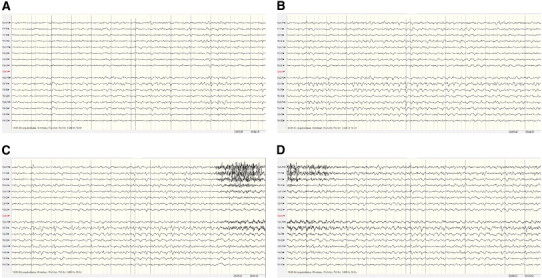

On Day 8 (Fig. 3), 70 electroclinical seizures were recorded, some with left temporal onset and others with right temporal onset. Six different propagation models were identified: a) some seizures showed regionalized onset in the temporal lobe followed by ipsilateral hemispheric propagation and then switch of lateralization; b) others with regionalized onset showed a switch of lateralization and temporal asynchrony; c) other seizures had a more hemispheric onset with early remote propagation; d) some seizures showed only hemispheric propagation; e) some nonlateralized onset seizures were recorded; and f) bitemporal onset seizures with nonclassifiable propagation models were also recorded.

Fig. 3.

Recording from Day 8: 70 seizures, independent onset in the right and left temporal lobes. Six propagation models (see text). EEG: left temporal onset with early remote propagation plus temporal asynchrony and switch of lateralization. Note the large area involved at the onset of the seizure and the difference in speed in the discharge's propagation to the contralateral hemisphere as compared to Fig. 2. (A–C) Without interruption, (D) 72 s after onset.

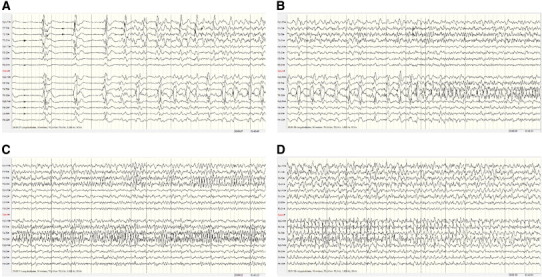

During the first month, frequent seizures were recorded with the propagation models described above, followed by a period (11 days) without seizures. However, when medication was reduced, the frequent electroclinical seizures reappeared, so thiopental had to be resumed. The EEG recordings at that time (Day 50, Fig. 4) identified 33 seizures, all of only right temporal onset; three propagation models were recognized: a) only ipsilateral hemispheric propagation, b) graduated and sequential, and c) some nonlateralized onset seizures.

Fig. 4.

Recording from Day 50: 33 seizures, onset only in the right temporal lobe. Three propagation models (see text). EEG: right temporal onset with graduated, sequential propagation. (A–D) Without interruption.

From Day 55 to Day 200, several unsuccessful attempts were made to suspend treatment with thiopental; the electroclinical seizures would reappear, starting independently over both temporal lobes, predominantly the right side, and with propagation models similar to those of the first month of recordings. It was finally possible to suspend thiopental on Day 270 after incorporating ketamine and midazolam IV into the treatment.

4. Discussion

In analyzing the course of our patient, we found, first, that the propagation models changed as the status evolved, and second, that the change in propagation models probably reflected the degree of excitability at that moment in the mesial temporal–limbic network. At times of high bitemporal excitability, manifested in a high number of seizures with independent onset over one temporal lobe or the other, we see that certain models of propagation begin to predominate, manifested through switch of lateralization, temporal asynchrony, early remote propagation, total contralateral propagation, and seizures with nonlocalized onset. These patterns appeared in combinations rather than alone, increasing the number of models observed and giving rise to propagation models that are difficult to classify. Conversely, when the condition was brought relatively under control, with ictal discharges starting only in the right temporal lobe, we observed fewer propagation models with predominantly simple patterns (only hemispheric propagation or graduated, sequential propagation with a few nonlateralized onset seizures).

Therefore, in an acute situation of this nature, propagation models become predominantly high or low excitability propagation patterns depending on the degree to which the seizures are controlled or the degree of excitability in the mesial temporal–limbic network at a given time.

The mechanisms that determine the propagation of a seizure are still unclear and may be different in different types of seizures. To connect the different types of propagation with varying excitability or network status is a simplification because other factors are involved in the spread of a seizure (e.g., reduced inhibition).

The propagation models described by Steinhoff et al. [7] and Schulz et al. [8] imply bitemporal hyperexcitability and are observed primarily in patients with independent interictal discharges in both temporal lobes. In this case, we observed that the propagation models described by these authors combine with our high excitability models, supporting the impression that the two methods of analysis are demonstrating a single phenomenon that manifests differently from the electroencephalographic point of view. Therefore, it does not seem logical to wonder which model is expressing a greater degree of excitability in the temporal lobe since, instead of one replacing the other, we see that they are usually associated. The presence of independent temporal interictal spikes could indicate that both temporal lobes are able to generate seizures or they could signal rapid propagation to the contralateral hemisphere [20]. Propagation with switch of lateralization and temporal asynchrony is a manifestation of the first phenomenon, while the models with early remote propagation and total contralateral propagation have to do with rapid propagation to the contralateral hemisphere.

It has been suggested that it is impossible to use scalp EEG to evaluate the speed with which the epileptic discharge propagates to the contralateral hemisphere in patients with MTE [21]. We suggest that the international 10–20 system with scalp electrodes, even without additional electrodes, can be used to identify seizures in which, a few seconds after the onset is observed, massive propagation is shown in the contralateral hemisphere. It is important to note that this type of propagation was seen frequently in this patient, and it can be identified easily among patients with independent bitemporal interictal discharges or in patients with independent onset seizures in both temporal lobes, sometimes as a single propagation pattern or, more frequently, associated with other high excitability models (in this respect, compare the differences in contralateral propagation speed seen in this patient's different EEG records).

It is frequently difficult to identify ictal epileptic episodes among critically ill patients being treated in the ICU with various medications and suffering from multiple medical complications. In this patient, identification of ictal EEG episodes, sometimes spontaneous and at other times induced by stimuli (procedures, bathing, and others), was strictly limited to those episodes with a definite onset and an epileptic discharge with clear evolution and propagation; recordings of periodic spontaneous or induced generalized epileptiform patterns were not taken into consideration.

Our work has several limitations, one of which is the fact that the analysis of the seizures is based on the observations of a single person (C.N.), so it is impossible to correct any bias arising from this factor. Another limitation is the fact that our ICU records do not cover 24 h per day, but we believe that the length of observation and the large number of seizures observed do allow us to chart the changes described in the propagation models.

To sum up, the findings observed in this patient show that propagation patterns do not remain static. They also show that certain propagation patterns seem to be associated with low excitability of the mesial temporal–limbic network, while other patterns are associated with high excitability of the mesial temporal–limbic network.

Persistence in time of seizures and the possibility that both temporal lobes can generate seizures seem to be determining factors to observe the variability of the patterns of propagation. Therefore, both elements must be considered when faced with partial status epilepticus affecting the temporal lobe that is extended in time. We have no information whether these changes in propagation patterns can be observed in other focal-onset status epilepticus.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Pablo Pulgar for his support and excellent work in ICU EEG recording.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Cayetano E. Napolitano, Email: napolitanonorero@manquehue.net.

Miguel A. Orriols, Email: morriols1@mac.com.

References

- 1.Lieb J.P., Engel J., Jr., Babb T.L. Interhemispheric propagation time of human hippocampal seizures. I. Relationship to surgical outcome. Epilepsia. 1986;27:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieb J.P., Dasheiff R.M., Engel J., Jr. Role of the frontal lobes in the propagation of mesial temporal lobe seizures. Epilepsia. 1991;32:822–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb05539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer S.S., Williamson P.D., Spencer D.D., Mattson R.H. Human hippocampal seizure spread studied by depth and subdural recording: the hippocampal commissure. Epilepsia. 1987;28:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer S.S., Marks D., Katz A., Kim J., Spencer D.D. Anatomic correlates of interhippocampal seizure propagation time. Epilepsia. 1992;33:862–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spencer S.S. Neural networks in human epilepsy: evidence of and implications for treatment. Epilepsia. 2002;43:219–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.26901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gloor P., Salanova V., Olivier A., Quesney L.F. The human dorsal hippocampal commissure. Brain. 1993;116:1249–1273. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinhoff B.J., So N.K., Lim S., Luders H.O. Ictal scalp EEG in temporal lobe epilepsy with unitemporal versus bitemporal interictal epileptiform discharges. Neurology. 1995;45:889–896. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz R., Luders H., Hoppe M., Tuxhorn I., May T., Ebner A. Interictal EEG and ictal scalp EEG propagation are highly predictive of surgical outcome in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:564–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassoux F., Semah F., Bouilleret V., Landre E., Devaux B., Turak B. Metabolic changes and electro-clinical patterns in mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy: a correlative study. Brain. 2004;127:164–174. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Napolitano C.E., Orriols M. Two types of remote propagation in mesial temporal epilepsy: analysis with scalp ictal EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;25:69–76. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31816a8f09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano C.E., Orriols M. Graduated and sequential propagation in mesial temporal epilepsy: analysis with scalp ictal EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;27:285–291. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181eaaa0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pataraia E., Lurger S., Serles W., Lindinger G., Aull S., Leutmezer F. Ictal scalp EEG in unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39:608–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walczak T.S., Lewis D., Radtke R. Scalp ictal EEG shows fewer focal characteristics in patient with bilateral interictal discharges. Neurology. 1991;41:261. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams C., Saint-Hilarie J., Richer F. Temporal and spatial characteristics of intracerebral seizure propagation: predictive value in surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1994;35:1065–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K.H., Park Y.D., King D.W., Meador K.J., Loring D.W., Murro A.M. Prognostic implication of contralateral secondary electrographic seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1444–1449. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancaster E., Martinez-Hernandez E., Dalmau J. Encephalitis and antibodies to synaptic and neuronal cell surface proteins. Neurology. 2011;77:179–189. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318224afde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shorvon S.D., Ferlisi M. The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011;134:2802–2818. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young G.B., Jordan K.G., Gordon S.D. An assessment of nonconvulsive seizures in the intensive care unit using continuous EEG monitoring: an investigation of variables associated with mortality. Neurology. 1996;47:83–89. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch L.J., Claassen J., Mayer S.A., Emerson R.G. Stimulus-induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges (SIRPIDs): a common EEG phenomenon in the critically ill. Epilepsia. 2004;45:109–123. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.38103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasco T.R., Wichert-Ana L., Leite J.P., Araujo D., Terra-Bustamante V.C., Alexandre V. Accuracy of ictal SPECT in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with bilateral interictal spikes. Neurology. 2002;59:266–271. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serles W., Pataraia E., Bacher J., Olbrich A., Aull S., Lehrner J. Clinical seizure lateralization in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: differences between patients with unitemporal and bitemporal interictal spikes. Neurology. 1998;50:742–747. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]