Abstract

Purpose

Ictal kissing has been described in the literature. Five cases were reported and associated with temporal lobe epilepsy lateralizing to the nondominant hemisphere.

Methods

A case of ictal kissing was identified. The aim was to demonstrate the clinical, clinical and electrophysiological features (as recorded by subdural electrodes). The surgical procedure, histopathology, and imaging data were reviewed and correlated with the literature.

Results

A 29-year-old right-handed female, who presented with ictal right hand left arm dystonic posturing, and lip smacking, was studied. The automatism was usually followed by prolonged emotional gestures and by hugging and kissing her relative and/or attendant nurse. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed right small cortical and subcortical lesions of the right inferior frontal lobe with gliosis but without mass effect and normal-sized hippocampi. The PET scan showed hypometabolism of the right temporal lobe. Neuropsychological evaluation showed deficit in her nonverbal memory. The subdural electrodes showed high amplitude spikes over right mesial temporal lobe strips. The offsite of the ictal discharges was usually at the right frontal strips. Right standard temporal lobectomy with amygdalohippocampectomy and right inferior frontal lesionectomy were performed. The patient continued to be seizure-free for one year postoperatively.

Conclusion

Our case report supports with subdural EEG recording the findings of the few reported cases of ictal kissing behavior lateralized to the nondominant hemisphere. However, the affectionate kissing behavior was associated with spread of the epileptic discharges to the right frontal lobe.

Keywords: Ictal kissing, Nondominant temporal lobe, Subdural EEG

1. Introduction

Automatisms with emotional behavior during seizures have been well described, including sudden changes in facial expression seen with chewing, manual automatisms, uncontrollable laughter, and ictal crying [1], [2], [3]. Ictal kissing is a rare phenomenon and has been described in previous patients [4], [5], [6]. The clinical significance and neurophysiological mechanisms of ictal kissing remain poorly understood. We describe a patient with ictal kissing and subdural EEG recording.

2. Clinical report

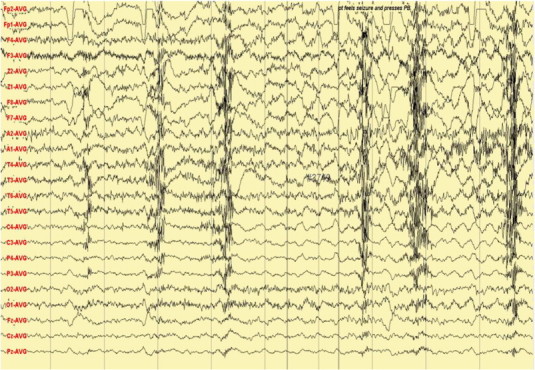

A 29-year-old right-handed female, who has a history of epilepsy for the last 10 years, was studied. The patient has no history of febrile convulsions. She has a history of an aura of fear followed by automatism consisting of right hand left upper limb dystonic posturing, and lip smacking. The automatism was usually followed by prolonged emotional gestures, hugging and kissing her relative and/or attendant nurse. The patient's seizure frequency varied from 1 to 2 per month. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed small cortical and subcortical lesions of the right inferior frontal lobe without mass effect or enhancement. The lesion was located directly anterior of the insular gyrus and inferior to the inferior frontal gyrus (Fig. 7). The hippocampi looked symmetrical (Fig. 8). The PET scan showed hypometabolism of the right temporal lobe (Fig. 9). Neuropsychological evaluation showed deficit in her nonverbal memory. The surface EEG showed right frontotemporal rhythmic slow wave activity (Fig. 1). Because of the uncertainty of the surface ictal EEG onset, the right inferior frontal lesion, and the normal-sized and symmetrical hippocampi, subdural EEG recording strips were done, covering the right temporal lobe and the right inferior frontal prelesional regions.

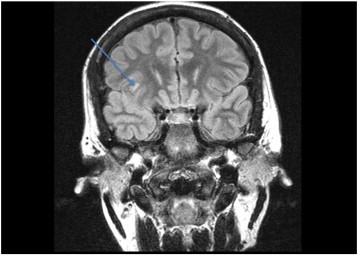

Fig. 7.

Brain MRI shows small cortical and subcortical lesions at the right inferior frontal lobe.

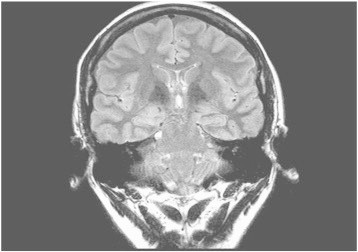

Fig. 8.

Brain MRI shows symmetrical normal-sized hippocampi.

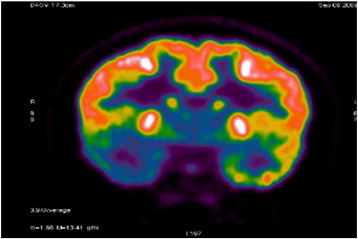

Fig. 9.

The PET study demonstrates decreased FDG metabolism involving the right temporal lobe.

Fig. 1.

Surface ictal EEG onset shows rhythmic slow waves over the right frontotemporal areas.

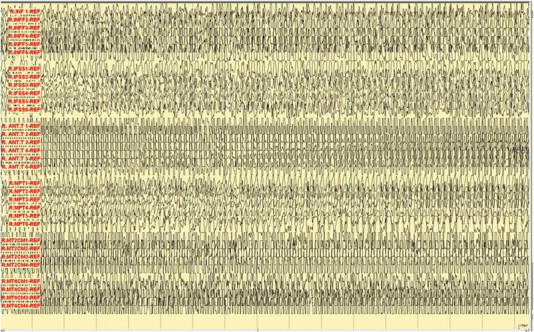

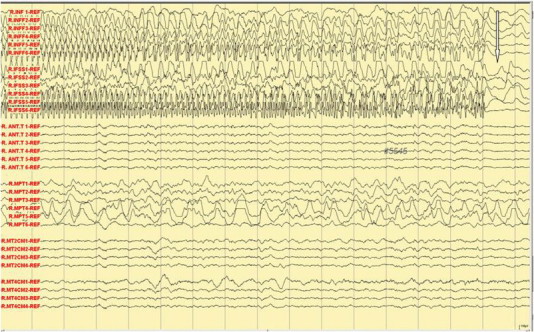

3. Invasive video-EEG recording

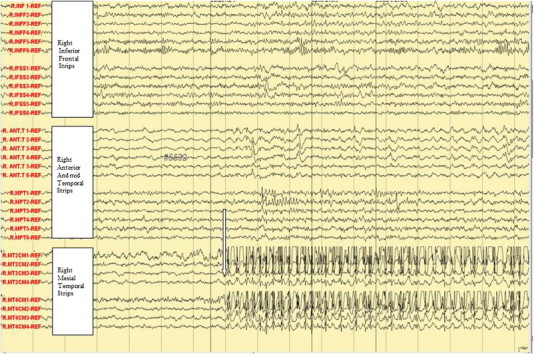

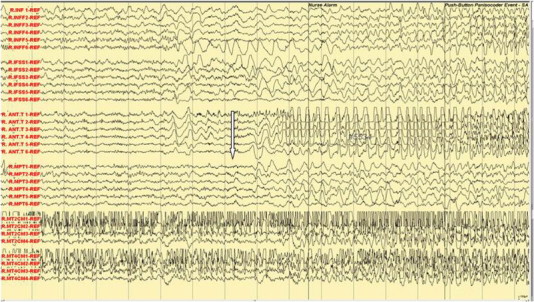

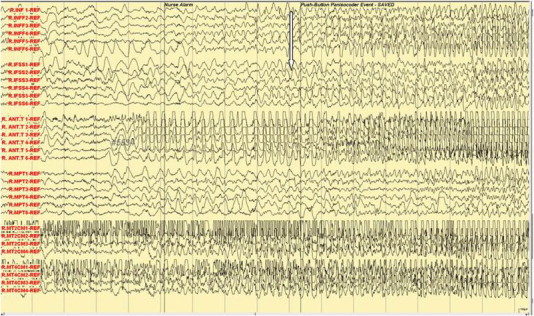

In the Epilepsy Unit, 5 push button events were recorded. The subdural electrodes showed clinical correlation of fear and palpitation with an onset of high amplitude spikes over right mesial temporal lobe strips (R-MT2, 4) (see arrow, Fig. 2). The manual automatism and lip smacking started at the appearance of the epileptic discharges at the anterior temporal strip (see arrow, Fig. 3). The emotional hugging and kissing behavior was correlated with the spread of the epileptic discharges in the frontal lobe (see arrow, Fig. 4) and (Fig. 5). The end of the kissing behavior was coupled to the offsite of the ictal discharge at the right frontal strips (see arrow, Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Ictal subdural EEG onset: aura of fear and palpitation.

Fig. 3.

Ictal subdural EEG: manual automatism and lip smacking.

Fig. 4.

Ictal subdural EEG: hugging and kissing and left arm dystonic posturing.

Fig. 5.

Ictal subdural EEG: more marked kissing behavior.

Fig. 6.

Ictal subdural EEG: end of the kissing behavior, no postictal confusion.

4. Epilepsy surgery

Right standard temporal lobectomy with amygdalohippocampectomy and lesionectomy of the right inferior frontal lobe under neuronavigation guidance was performed. The patient continued to be seizure-free for one year. Histopathology of the hippocampus and the inferior frontal lesion was compatible with gliosis.

5. Discussion

Fear, anxiety, and emotional distress are among the most frequently reported behaviors in epilepsy. However, varieties of ictal automatisms with other emotional elements also have been described [7], [8]. Religious experiences occurring in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy are also described [9]. In addition, the association of ictal kissing with religious speech in a patient with right temporal lobe epilepsy has been well characterized [5].

The kissing and hugging behavior is an interesting feature of temporal lobe epilepsy and has been described in the literature [4], [5], [6]. Five cases were reported and associated with TLE lateralizing to the nondominant hemisphere. Three of them were associated with mesiotemporal sclerosis, one with a benign tumor, and one with a normal MRI. Our case is considered another example of ictal kissing with normal and symmetrical size hippocampi in brain MRI. The histopathology of the right hippocampus showed mild gliosis, and there was a gliotic lesion in the inferior frontal lobe, just anterior to the insula; however, it was not related to the ictal EEG onset. Three out of the five reported cases were operated, and the histopathologies were hippocampus sclerosis, cortical dysplasia, and low grade astrocytoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of the reported cases.

| Case 1 Rashid et al. [6] |

Case 2 Rashid et al. [6] |

Case 3 Rashid et al. [6] |

Case 4 Ozkara et al. [5] |

Case 5 Mikati et al. [4] |

Case 6 Alsemari et al. 2013 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39 | 46 | 48 | 25 | 24 | 29 |

| Imaging findings | MRI: no abnormality | MRI: R mesial temporal sclerosis | MRI: R mesial temporal sclerosis | MRI: R mesial sclerosis, | MRI: R mesial temporal lesion | MRI: small cortical and subcortical lesions at the right inferior frontal lobe without mass effect or enhancement; the hippocampi looked symmetrical |

| Histopathology | Cortical dysplasia type IIa | No surgery | No surgery | Hippocampal sclerosis | Low grade astrocytoma | Mild gliosis |

| Interictal EEG | SW, R temporal | SW, R temporal | SW, R > L temporal | SPK, R > L temporal | Unknown | SW, R temporal |

| Ictal EEG | Rhythmic theta activity maximum at F8-T8 and SP2, evolving into a high amplitude 7-Hz rhythm maximum over the R temporal region | Rhythmic theta activity beginning in the R temporal region, spreading to the frontal lobes (R > L) and evolving into polymorphic slowing | Theta activity in the R frontotemporal region evolving into rhythmic generalized slowing | Semi rhythmic theta activity over the right frontotemporal region, evolving to bifrontotemporal slowing | Rhythmic theta activity maximum F8 and SP2, in some seizures evolving to bilateral frontotemporal slowing with right-sided predominance | High amplitude spike discharges over right mesial temporal lobe strips spreading to the frontal lobe strips |

The kissing ictal behavior was similar to typical behaviors seen with complex partial seizures, such as chewing, lip smacking, fumbling, tapping, rubbing, or other semipurposeful, repetitive movements. Our subdural EEG recording showed that the ictal epileptic discharge onset was at the right temporal lobe, and it was correlated well with the common manual and mouth automatism. Nevertheless, the spread of epileptic discharges in the frontal lobe was associated with the kissing and the affectionate behavior.

Epileptic seizures may cause dysfunction not only through excitation but also by inhibition of neuronal activity that extends beyond the area directly involved in the electrographic seizure activity, leading to behavioral dysfunction [6]. Inhibition of neuronal activity extends sometimes into the postictal period and can cause ongoing release of behavior control and, not uncommonly, postictal automatisms.

The affectionate behavior is a rare clinical manifestation in epilepsy; however, it is of scientific value in defining the cerebral circuitry of emotion. The feeling of affection for attachment and the underlying basis of human behavior have become important research themes in neuroscience. After the introduction of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neuroscientists have demonstrated increased interest in the neurobiology and neurochemistry of emotions, including love and affection [10]. Epilepsy with kissing and sexual behavior is considered exaggerated behavioral phenomena and may assist in facilitating the discovery of the outlines of the physiology of romance.

Few fMRI studies elucidating neural correlates of romantic and affection have been published [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. These studies are difficult to compare because they suffer from selection bias. However, some general conclusions can be drawn from these neuroimaging studies. The brain areas that show activation in romantic love were the medial insula, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, striatum, nucleus accumbens, and hypothalamus.

In conclusion, our findings support the idea that the ictal kissing behavior is a phenomenon of nondominant temporal lobe epilepsy. However, it is possibly linked to a circuit involving regions beyond the temporal lobe, such as the medial insula, anterior cingulate cortex, medial orbitofrontal, and hippocampus in the nondominant hemisphere.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Arroyo S., Lesser R.P., Gordon B., Uematsu S., Hart J., Schwerdt P. Mirth, laughter and gelastic seizures. Brain. Aug. 1993;116(4):757–780. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.4.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenard H.G. Dacrystic seizures reconsidered. Neuropediatrics. Apr. 1999;30(2):107–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meletti S., Tassi L., Mai R., Fini N., Tassinari C.A., Russo G.L. Emotions induced by intracerebral electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe. Epilepsia. 2006;Suppl 5:47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikati M.A., Comair Y.G., Shamseddine A.N. Pattern-induced partial seizures with repetitive affectionate kissing: an unusual manifestation of right temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. May 2005;6(3):447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozkara C., Sary H., Hanoglu L., Yeni N., Aydogdu I., Ozyurt E. Ictal kissing and religious speech in a patient with right temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. Dec. 2004;6(4):241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashid R.M., Eder K., Rosenow J., Macken M.P., Schuele S.U. Ictal kissing: a release phenomenon in non-dominant temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. Dec. 2010;12(4):262–269. doi: 10.1684/epd.2010.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumer M.M., Atik L., Unal A., Emre U., Atasoy H.T. Frontal lobe epilepsy presented as ictal aggression. Neurol Sci. Mar. 2007;28(1):48–51. doi: 10.1007/s10072-007-0749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kligman D., Goldberg D.A. Temporal lobe epilepsy and aggression. J Nerv Ment Dis. May 1975;160(5):324–341. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewhurst K., Beard A.W. Sudden religious conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. Feb. 2003;4(1):78–87. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00688-1. 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boer A., van Buel E.M., Ter Horst G.J. Love is more than just a kiss: a neurobiological perspective on love and affection. Neuroscience. Jan. 10 2012;201:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartels A., Zeki S. The neural basis of romantic love. Neuroreport. Nov. 27 2000;11(17):3829–3834. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011270-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels A., Zeki S. The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage. Mar. 2004;21(3):1155–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher H., Aron A., Brown L.L. Romantic love: an fMRI study of a neural mechanism for mate choice. J Comp Neurol. Dec. 5 2005;493(1):58–62. doi: 10.1002/cne.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aron A., Fisher H., Mashek D.J., Strong G., Li H., Brown L.L. Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. J Neurophysiol. Jul. 2005;94(1):327–337. doi: 10.1152/jn.00838.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauregard M., Courtemanche J., Paquette V., St-Pierre E.L. The neural basis of unconditional love. Psychiatry Res. May 15 2009;172(2):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeki S. The neurobiology of love. FEBS Lett. Jun. 12 2007;581(14):2575–2579. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X., Aron A., Brown L., Cao G., Feng T., Weng X. Reward and motivation systems: a brain mapping study of early-stage intense romantic love in Chinese participants. Hum Brain Mapp. Feb. 2011;32(2):249–257. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]