Abstract

Synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids, originally developed to probe cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors, have become widely abused for their marijuana-like intoxicating properties. The present study examined the effects of indole-derived cannabinoids in rats trained to discriminate Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) from vehicle. In addition, the effects of Δ9-THC in rats trained to discriminate JWH-018 from vehicle were assessed. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were trained to discriminate 3 mg/kg Δ9-THC or 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018 from vehicle. JWH-018, JWH-073, and JWH-210 fully substituted in Δ9-THC-trained rats and Δ9-THC substituted in JWH-018-trained rats. In contrast, JWH-320, an indole-derived cannabinoid without affinity for CB1 receptors, failed to substitute for Δ9-THC. Pre-treatment with 1 mg/kg rimonabant significantly reduced responding on the JWH-018-associated lever in JWH-018-trained rats. These results support the conclusion that the interoceptive effects of Δ9-THC and synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids show a large degree of overlap, which is predictive of their use for their marijuana-like intoxicating properties. Characterization of the extent of pharmacological differences among structural classes of cannabinoids, and determination of their mechanisms remain important goals.

Keywords: discriminative stimulus, indole cannabinoids, JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-210, synthetic cannabinoids, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

1.0 Introduction

Synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids were originally developed as research tools to probe cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors (Aung, et al., 2000; Huffman, 2000; Huffman, et al., 1994; Wiley, et al., 2011). Over the past decade, however, some of these compounds have been synthesized illicitly, sprayed on plant material, marketed in brightly colored packages labeled “not for human consumption,” and, despite this warning, regularly smoked for their marijuana-like intoxicating properties (Vardakou, et al., 2010). Abuse of synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids has rapidly increased to the point of becoming a substantial international social and public health issue, which continues to be fueled by the steady influx of new compounds available for online purchase as the “old” compounds are banned (Tofighi and Lee, 2012; Uchiyama, et al., 2013; Winstock and Barratt, 2013). Because initial structure-activity relationship studies focused primarily on binding data (reviewed in Huffman, 1999; Huffman and Padgett, 2005; Manera, et al., 2008), the preclinical in vivo pharmacology of most synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids remained poorly characterized, although there are a few early studies including in vivo pharmacology (Wiley, et al., 1995a; Wiley, et al., 1998).

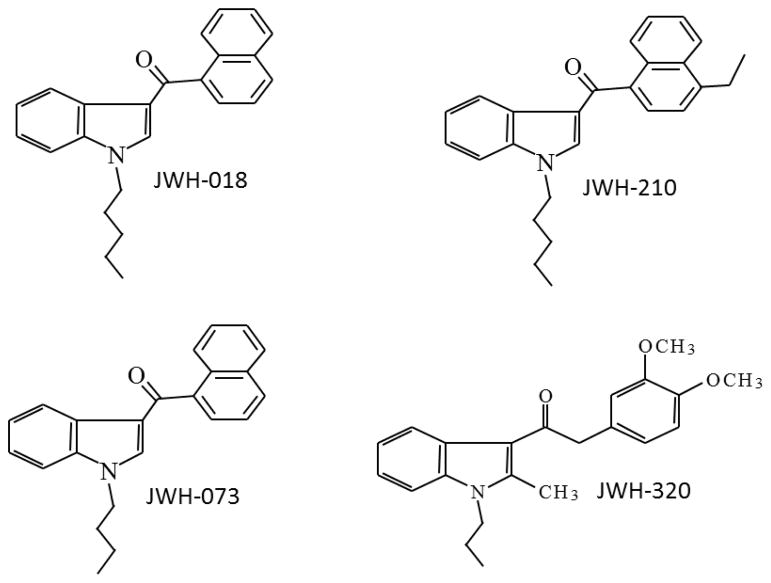

As abuse of indole-derived synthetic cannabinoids has become more widespread, additional studies examining their in vivo effects have appeared in the scientific literature (Brents, et al., 2013; Seely, et al., 2012; Wiebelhaus, et al., 2012; Wiley, et al., 2012). Several studies have utilized Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) discrimination, a pharmacologically selective animal model of marijuana intoxication (Balster and Prescott, 1992), as a way to evaluate the abuse liability of these compounds. In rats, the prototypic bicyclic and aminoalkylindole synthetic cannabinoids, CP55,940 and WIN55,212-2, respectively, dose-dependently substitute and cross-substitute for Δ9-THC (Compton, et al., 1992; Gold, et al., 1992; Perio, et al., 1996; Wiley, et al., 1995b). Compounds with alkyl group (butyl to hexyl) substitution for the morpholinoethyl group of WIN55,212-2 also dose-dependently substituted in CP55,940-trained rats at potencies consistent with their CB1 affinity, whereas the heptyl compound did not substitute, nor did it bind to CB1 receptors (Wiley, et al., 1998). Later studies showed that indole-derived cannabinoids JWH-018, JWH-073, AM-2233, and AM-5983 also substituted for Δ9-THC in rats and/or rhesus monkeys (Brents, et al., 2013; Ginsburg, et al., 2012; Järbe, et al., 2010; Järbe, et al., 2011; Marusich, et al., 2013), with rimonabant reversal suggesting CB1 mediation of their Δ9-THC-like effects (Ginsburg, et al., 2012; Järbe, et al., 2011). In Δ9-THC-trained mice, two phenylacetylindoles (JWH-204 and JWH-205) and two tetramethylcyclopropyl ketone indoles (UR-144 and XLR-11) with high affinity (Ki < 30 nM) for the CB1 receptor substituted, whereas another phenylacetylindole (JWH-202) with low affinity (Ki > 1500 nM) did not (Vann, et al., 2009; Wiley, et al., 2013). In the present study, rats were trained to discriminate Δ9-THC from vehicle. Subsequently, JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-210, and JWH-320 were evaluated (see Figure 1 for chemical structures). JWH-018 was chosen as a test compound because it was the first synthetic cannabinoid to be identified in a confiscated product (hence, it is considered to be the prototypic abused indole-derived cannabinoid). For this reason, it was also chosen as the training drug for a separate discrimination described in more detail below. JWH-073 is structurally similar to JWH-018 and was also a compound found in early abused products. JWH-210 was chosen as a test compound because of the presence of a manipulation in the naphthoyl component of the template JWH-018 structure (see Figure 1). While compounds with substitution of the complete naphthoyl component have been assessed in drug discrimination (e.g., tetramethylcyclopropyl ketones and phenylacetylindoles), compounds with methyl additions to the naphthoyl have not been tested in this procedure, although they have appeared in confiscated products. JWH-320 was tested as a negative control for the procedure. Although it is structurally similar to other indoles that have been abused, it does not bind to the CB1 receptor. In addition, a novel discrimination (JWH-018) was trained in a separate group of rats. Following demonstration of acquisition of the JWH-018 discrimination and training drug dose-effect curve, cross-substitution tests with Δ9-THC were undertaken to determine the overlap of traditional and synthetic cannabinoids, and CB1 receptor mediation was evaluated by assessment of antagonism of JWH-018’s discriminative stimulus effects by the CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, rimonabant.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-210, and JWH-320.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Adult male drug naïve and experimentally naïve Sprague-Dawley rats (total n=16) (Harlan Laboratories, Dublin, VA, USA) were individually housed upon arrival in polycarbonate cages with hardwood bedding in a temperature-controlled (20–22°C) environment with a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6am). Rats were maintained at 85–90% of free-feeding body weights by restricting their daily ration of rodent chow (Purina® Certified 5002 Rodent Chow, Barnes Supply, Durham, NC, USA). Water was available ad libitum in their home cages. All experiments were carried out in accordance with guidelines published in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011), and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at RTI. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, to reduce the number of animals used, and to utilize alternatives to in vivo techniques, if available.

2.2 Apparatus

Standard rat operant chambers (Habitest Modular System, Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA, USA) were enclosed in light- and sound-attenuating isolation cubicles equipped with exhaust fans. Each operant chamber contained a house light near the ceiling, 2 retractable levers, a stimulus light panel above each lever, and a food cup with a light located between the levers. A pellet dispenser, located outside of the chamber, delivered 45 mg pellets (Bioserv Inc., Frenchtown, NJ, USA) into the food cup accompanied by illumination of the food cup light. During sessions, ~80 db of white noise was delivered via a speaker located inside the isolation cubicle. Illumination of lights, delivery of food pellets, and recording of lever presses were controlled by a computer-based system (Coulbourn Instruments, Graphic State Software, v 3.03).

2.3 Procedure

Rats were randomly assigned to two groups (n=8/group), and were trained to press one lever following administration of a cannabinoid (3 mg/kg Δ9-THC or 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018, respectively) and to press another lever after injection with vehicle (7.8 % Polysorbate 80 and 92.2% sterile saline). On the first training session rats were exposed to the operant chamber for 60 min during which a pellet was dispensed after an average of 60 s. On days 2 and 3 rats were exposed to a 60 min session during which one lever was extended for the duration of the session with the stimulus light above that lever illuminated, and lever presses were reinforced on a fixed ratio 1 (FR 1) schedule of food reinforcement. The opposite lever was extended on the second day of lever training. The fixed ratio requirement was gradually increased from FR 1 to FR 10 across the next 22 sessions which were 15 min in duration. The side of the chamber with the active lever alternated daily. Prior to sessions 26–37 injections of either vehicle or drug (3.0 mg/kg Δ9-THC or 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018) were administered, and only the appropriate lever was extended. Rats were then assigned a drug lever and vehicle lever for the remainder of the study (i.e., vehicle=left, drug=right). Responding on the assigned lever after the appropriate injection resulted in reinforcement.

Baseline sessions then began with lever pressing on the correct lever reinforced on an FR 10, and each response on the incorrect lever reset the response requirement on the correct lever. The position of the drug lever was counterbalanced among the group of rats. The daily injections for each rat were administered in a double alternation sequence of training drug and vehicle (e.g., drug, drug, vehicle, vehicle). Rats were injected and returned to their home cages until the start of the experimental session. Training occurred during 15-min sessions conducted five days a week (Monday-Friday) until the rats had met three criteria during eight of ten consecutive sessions: (1) the first completed FR-10 was on the correct lever; (2) the percentage of correct-lever responding was ≥ 80% for the entire session; and (3) the response rate was ≥ 0.2 responses/s.

Following successful acquisition of the discrimination, stimulus substitution tests with test compounds were typically conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays during 15-min test sessions. Training continued on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. During test sessions, responses on either lever delivered reinforcement according to a FR-10 schedule. In order to be tested, rats must have completed the first FR on the injection-appropriate lever, made at least 80% of all responses on the injection-appropriate lever, and had a response rate ≥ 0.2 responses/s during the preceding day’s training session.

A dose-effect determination with the training drug (Δ9-THC or JWH-018) was performed first in each rat. Subsequently, the Δ9-THC-trained group was tested with JWH-018, JWH-210, JWH-073, and JWH-320. One test session for each dose of each drug was conducted. Doses of each compound were administered in ascending order. After completion of the dose-effect curve with the training drug, the JWH-018 group was tested with Δ9-THC followed by an antagonism test with a combination of 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018 and 1 mg/kg rimonabant. Throughout the study, control tests with vehicle and the training drug were conducted before the start of each dose-effect curve determination. During these control tests, both levers were active, which distinguishes the procedure for these tests from that used for the criteria training sessions described in the preceding paragraph. Experiments were conducted between the hours of 8 a.m. and 5 p.m.

2.4 Drugs

Δ9-THC [National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Bethesda, MD, USA], JWH-018 (NIDA), JWH-073 (NIDA), JWH-210 (NIDA), and JWH-320 (provided by John Huffman, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA) were suspended in a vehicle of 7.8 % Polysorbate 80 N.F. (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) and sterile saline USP (Butler Schein, Dublin, OH, USA). All drugs were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a volume of 1 ml/kg 30 min prior to the start of the session, except rimonabant which was injected 10 min before injection with JWH-018.

2.5 Data Analysis

For each test session, mean (±SEM) percent responding on the drug lever and rate of responding (responses/s) were calculated for the entire session. Full substitution was operationally defined as ≥ 80% responding on the training drug-associated lever. When appropriate, ED50s (and 95% confidence limits) were calculated separately for each drug using least-squares linear regression on the linear part of the dose-effect curves for percent drug-lever responding, plotted against log10 transformation of the dose. Because rats that responded less than 10 times during a test session did not press either lever a sufficient number of times to earn a reinforcer, their lever selection data were excluded from data analysis, but their data were included in response rate calculations. Response-rate data were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) across dose. Repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to compare percent of drug lever responding and response rates for antagonism tests in the JWH-018-trained rats, comparing 3 treatment conditions: 1) vehicle, 2) 0.3 mg/kg training dose of JWH-018, and 3) combination of 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018 and 1 mg/kg rimonabant. A mean substitution procedure was used to maintain equal n’s across conditions in the case of missing data (i.e., 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC was not tested in 2 rats in the JWH-018-trained group and 1 rat in the JWH-018-trained group did not respond when tested with the JWH-018 and rimonabant combination). Significant ANOVAs were followed by Tukey post hoc tests (α = 0.05) to determine differences between means.

3.0 Results

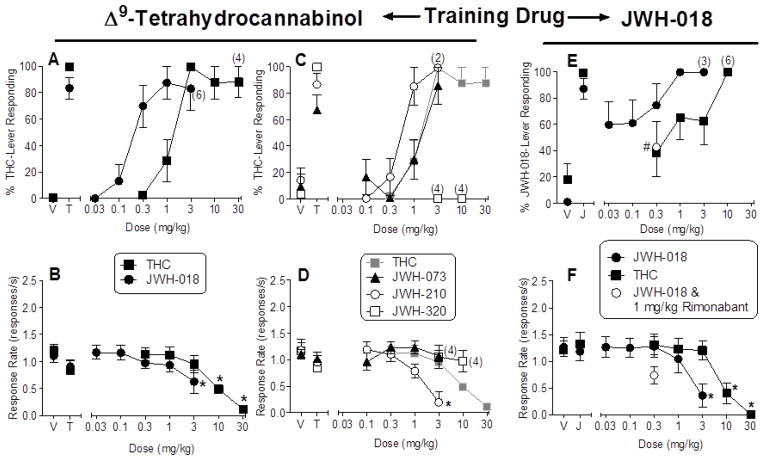

Acquisition of the Δ9-THC discrimination required an average of 16.5 sessions (± 2.96; range = 10–32) [data not shown]. As shown in Figure 1 (left side of panel A), rats responded predominantly on the vehicle-associated lever when injected with vehicle (V) and on the Δ9-THC (T)-associated lever when injected with the training dose (3 mg/kg) of Δ9-THC. Results of substitution tests with Δ9-THC and JWH-018 showed that both of these substances substituted fully and dose dependently for the Δ9-THC training dose (3 mg/kg) in Δ9-THC-trained rats (Fig. 1, right side of panel A). Further, consistent with its lower nM Ki for the CB1 receptor, JWH-018 was approximately 5-fold more potent than Δ9-THC (Table 1). Higher doses of Δ9-THC (10 and 30 mg/kg) and JWH-018 (3 mg/kg) significantly decreased overall response rates [Δ9-THC: F(5,35)=17.85, p<0.05; JWH-018: F(5,35)=6.38, p<0.05; Fig. 1, panel B].

Table 1.

CB1 and CB2 receptor affinities and in vivo potencies in drug discrimination of synthetic cannabinoids

| Compound (MW) | Affinities Ki (nM) ± SEM | ED50 (mg/kg) (95% confidence limits) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB1 Ki | CB2 Ki | Δ9-THC DD | JWH-018 DD | |

| Δ9-THC (314) | 40.7 ± 1.7a | 36.4 ± 10a | 1.13 (0.89 – 1.43) | 0.62 (0.14 – 2.67) |

| JWH-018 (341) | 9 ± 5b | 3 ± 2.6b | 0.23 (0.15 – 0.35) | < 0.03 (outside of range tested) |

| JWH-073 (327) | 8.9 ± 1.8b | 38 ± 24b | 1.31 (1.12 – 1.53) | not tested |

| JWH-210 (369) | 0.46 ± 0.03c | 0.69 ± 0.01c | 1.23 (0.75 – 2.02) | not tested |

| JWH-320 (351) | > 10,000 | not determined | no substitution | not tested |

DD = drug discrimination. MW = molecular weight. SEM = standard error of the mean.

Panel C of Figure 1 shows the effects of JWH-073, JWH-210, and JWH-320 in Δ9-THC-trained rats. Whereas full substitution for Δ9-THC was obtained with the training dose prior to tests with JWH-210 and JWH-320, only 67% drug-lever responding was seen in the control test with Δ9-THC prior to tests with JWH-073 (left side of Fig. 1, panel C), prompting the addition of extra training days for some rats before testing JWH-073. Responding on vehicle control days prior to testing of each compound was primarily on the vehicle-associated lever. Dose-response curves for JWH-073 and JWH-210 are shown in the main part of panel C. Like JWH-018, these two compounds have higher CB1 receptor affinities (i.e., lower nM Ki values) than Δ9-THC (Table 1) and both fully substituted for Δ9-THC at higher doses (Fig. 1, panel C). Interestingly, however, JWH-073, JWH-210, and Δ9-THC showed approximately equipotent substitution (and overlapping 95% confidence limits), despite the substantially higher affinities of the synthetic cannabinoids for binding to CB1 receptors (Table 1). In contrast with the other indole-derived cannabinoids, JWH-320 failed to substitute for Δ9-THC at either dose tested (Fig. 1, panel C). This result is consistent with its low affinity for the CB1 receptor (Table 1). Response rates were significantly decreased by 3 mg/kg JWH-210 [F(4,24)=12.9, p<0.05], but were unaffected by JWH-073 and JWH-320 (Fig. 1, panel D).

Acquisition of the JWH-018 discrimination required an average of 20.38 sessions (± 5.45, range = 10–57) [data not shown]. As shown in Figure 1 (left side of panel E), rats responded predominantly on the vehicle-associated lever when injected with vehicle (V) and on the JWH-018 (J)-associated lever when injected with the training dose (0.3 mg/kg) of JWH-018. Results of substitution tests with JWH-018 and Δ9-THC showed that each drug substituted fully at higher doses (Fig. 1, right side of panel E). Again, JWH-018 showed greater (> 20-fold) potency for substitution than did Δ9-THC (Table 1) and both drugs significantly decreased response rates at higher doses [JWH-018: F(5,35)=8.19, p<0.05; Δ9-THC: F(5,35)=8.19, p<0.05; Fig. 1, panel F]. Pre-treatment with 1 mg/kg rimonabant significantly reduced responding on the JWH-018-associated lever compared to responding on this lever following injection with 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018 alone (Fig. 1, right side of panel F), but percent JWH-018-lever responding also remained significantly elevated compared with vehicle [F(2,14)=14.83, p<0.05; Fig. 1, panel E]. The rimonabant and JWH-018 combination did not significantly alter response rates compared to vehicle.

4.0 Discussion

Consistent with numerous previous studies (for reviews, see Balster and Prescott, 1992; Tanda and Goldberg, 2003; Wiley, 1999), Δ9-THC served as a discriminative stimulus and produced full, dose-dependent substitution for the 3 mg/kg training dose. JWH-018 and JWH-073, two of the earliest synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids identified in abused products (Dresen, et al., 2010), exhibited similar full and dose-dependent substitution for Δ9-THC, as has also been shown in previous studies in rats (Järbe, et al., 2011), mice (Brents et al., 2013), and monkeys (Ginsburg, et al., 2012). In addition, an early study reported that structurally similar analogs of these two compounds fully substituted in rats trained to discriminate the bicyclic cannabinoid CP55,940 from vehicle (Wiley, et al., 1998), with the JWH-073-like compound also substituting for Δ9-THC in Δ9-THC-trained rhesus monkeys (Wiley, et al., 1995a). [JWH-073 is structurally similar to the n-butyl, and JWH-018 to the n-pentyl, analogs of 1-alkyl-2-methyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole (JWH-016 and JWH-007, respectively), with the exception that JWH-018 and JWH-073 lack the 2-methyl group contained in the other two analogs (Wiley, et al., 1998).] Not surprisingly (given its high CB1 receptor affinity), JWH-210 also substituted for Δ9-THC in the present study whereas JWH-320, which has very low affinity for the CB1 receptor (Ki > 10,000 nM), did not. While the compounds detected earliest in the abuse epidemic tended to be 1-alkyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indoles with various alkyl substituents (e.g., n-pentyl and n-butyl for JWH-018 and JWH-073, respectively, and n-fluoropentyl for AM-2201), structural manipulations in JWH-210 and JWH-320 occur on the naphthoyl substituent (see Figure 1). Recently, JWH-210 has been detected in confiscated products (U S Drug Enforcement Administration, 2013), as have two indole-derived tetramethylcyclopropyl ketone analogs (UR-144 and XLR-11) (U S Drug Enforcement Administration, 2013; Uchiyama, et al., 2013). The increased detection of compounds with structural manipulation of or substitution for the naphthoyl substituent of the original 1-alkyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole template suggests a new direction in which illicit synthesis is moving. Substitution of JWH-210 (present study) and the tetracyclopropyl ketone analogs (Wiley, et al., 2013) for Δ9-THC in drug discrimination suggests that this preclinical method may aid in prediction of which structural manipulations are likely to result in compounds with Δ9-THC-like abuse potential. Given the apparent trend towards manipulation of the naphthoyl substituent, reports of Δ9-THC-like effects of the 1-pentyl-3-phenylacetylindoles, JWH-204 and JWH-205, in Δ9-THC-trained mice (Vann, et al., 2009) suggest potential new forensic targets.

Although substitution of synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids with high CB1 receptor affinity is not unexpected, the similarity in potencies of the Δ9-THC-like discriminative stimulus effects of JWH-073, JWH-210, and Δ9-THC is notable, given that JWH-073 and JWH-210 have greater affinity for the CB1 receptor than Δ9-THC (Table 1). This type of discrepancy between CB1 receptor affinity and potency across cannabinoid classes within a single study has been noted in some, but not all (JWH-018 in present study; Compton, et al., 1992; Perio, et al., 1996), previous cannabinoid discrimination studies. For example, despite its higher affinity, WIN55,212-2 (CB1 Ki = 24 nM; Wiley et al., 1998) was less potent in substituting in a cannabinoid discrimination procedure than was Δ9-THC (CB1 Ki = 41 nM; Wiley et al., 1998) in rats (Järbe, et al., 2011; Wiley, et al., 1995b) and rhesus monkeys (Wiley, et al., 1995a). Similarly, JWH-073 and 1-alkyl-2-methyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indoles, all of which had higher CB1 affinities than Δ9-THC, nevertheless showed poorer potency for substitution in cannabinoid discrimination procedures in rats and rhesus monkeys (present study; Ginsburg, et al., 2012; Wiley, et al., 1995a; Wiley, et al., 1998). While the mechanism(s) for these potency disparities remain(s) unidentified, possibilities include increased efficacy (Atwood, et al., 2010; Atwood, et al., 2011) and/or differential interaction of synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids with CB1 receptors (compared to Δ9-THC) (Song and Bonner, 1996), modulation of their potency by action at CB2 and/or other cannabinoid or non-cannabinoid receptors (Aung, et al., 2000; Breivogel, et al., 2001; Hajos, et al., 2001), and pharmacokinetic considerations such as effects of metabolites (Brents, et al., 2012).

Another goal of the present study was to establish a discrimination based on JWH-018. Until recently, the aminoalkylindole WIN55,212-2 was the only indole-derived cannabinoid that had been trained as a discriminative stimulus (Perio et al., 1996). Earlier this year, however, Järbe et al. (2014) trained rats to discriminate various doses of the indole-derived cannabinoid, AM5983. Similar to WIN55,212-2 and AM5983, JWH-018 was readily trained as a discriminative stimulus, producing full and dose-dependent substitution for the 0.3 mg/kg training dose. Further, substitution was attenuated by rimonabant, as has also been shown with WIN55,212-2 (Perio et al., 1996), albeit full reversal to vehicle levels was not achieved with 1 mg/kg rimonabant in the present study. While full cross-substitution of Δ9-THC occurred at a dose of 10 mg/kg, this dose was also associated with significant reduction in overall responding, and responding was absent in most rats at a higher dose (30 mg/kg). The ED50 of Δ9-THC for substitution for itself was almost 2-fold greater than its substitution for JWH-018. In contrast, the ED50 of JWH-018 for substitution for itself was approximately 11-fold greater than its substitution for Δ9-THC. These quantitative differences may suggest differences in the potency or efficacy of the training dose of each compound. Previous studies have demonstrated that training dose influences which drugs substitute as well as the dose-response functions for these drugs (De Vry and Slangen, 1986; Mansbach and Balster, 1991; Young et al., 1992). For example, methanandamide fully substituted in rats trained to discriminate 1.8 mg/kg Δ9-THC, but only partially substituted in rats trained to discriminate 5.6 mg/kg Δ9-THC (Järbe et al., 2000; Järbe et al., 1998). Efficacy differences have also been shown to affect ED50 values for cross-substitution of full and partial cannabinoid agonists (Järbe et al., 2014). In the present study, Δ9-THC and JWH-018 fully substituted and cross-substituted for each other; however, potency differences between the two drugs was greater in the JWH-018 discrimination than in the Δ9-THC discrimination (about 30-fold versus 5-fold, respectively). In addition, Δ9-THC maximal cross-substitution for JWH-018 was accompanied by response rate decreases whereas its substitution for itself was not. These results suggest the possibility of a qualitative difference (as well as a quantitative difference) in the pharmacological properties of Δ9-THC and synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids, although this study remains limited in its ability to distinguish among several possible explanations of this difference.

In summary, results of drug discrimination studies, including the present one, have revealed a large degree of overlap in the interoceptive effects of Δ9-THC and synthetic indole-derived cannabinoids and are predictive of the use of these compounds for their marijuana-like intoxicating properties in humans. Yet, despite the similarities between Δ9-THC and indole-derived cannabinoids, differences are starting to appear as these compounds receive increased research attention. For example, notable herein are discrepancies between relative potencies of the compounds and their relative CB1 receptor binding affinities and differences in Δ9-THC and JWH-018 cross-substitution profiles. Characterization of the extent of pharmacological differences among structural classes of cannabinoids and determination of their mechanistic underpinnings remain important goals. Hence, these structurally diverse cannabinoids may still have usefulness as research tools even as their abuse presents challenges to forensic and law enforcement agencies.

Figure 2.

Panel A shows the effects of Δ9-THC and JWH-018 on percentage of Δ9-THC-lever responding in rats trained to discriminate 3 mg/kg Δ9-THC from vehicle. Response rates for these dose-effect curves are shown in panel B. Panel C shows the effects of JWH-073, JWH-210, and JWH-320 in the same group of Δ9-THC-trained rats. For ease of comparison, results of Δ9-THC are presented again (in greytone). Response rates for these dose-effect curves are shown in panel D. Panel E presents the effects of JWH-018 and Δ9-THC on percentage of JWH-018-lever responding in rats trained to discriminate 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018 from vehicle. Results of an antagonist test with 1 mg/kg rimonabant and the training dose (0.3 mg/kg) of JWH-018 are also shown. Response rates for these tests are shown in panel F. In panels A–D, points above V and T represent the results of control tests with vehicle and 3 mg/kg Δ9-THC conducted before each dose-effect determination. In panels E–F, points above V and J represent the results of control tests with vehicle and 0.3 mg/kg JWH-018. For each dose-effect curve determination, values represent the mean (± SEM) of 7–8 rats, except as indicated by numbers in parentheses in the panels. For agonist tests, asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference in response rates (p < 0.05) relative to the vehicle condition. For the antagonist test (panel E), number sign (#) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) of JWH-018 plus rimonabant, relative to vehicle and to JWH-018 tested alone.

Highlights.

Synthetic cannabinoids are widely abused for their marijuana-like properties.

Rats were trained to discriminate Δ9-THC or JWH-018 from vehicle.

JWH-018, JWH-073, and JWH-210 fully substituted for Δ9-THC.

Δ9-THC fully substituted for JWH-018.

The interoceptive effects of Δ9-THC and synthetic cannabinoids show much overlap.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by NIH/NIDA Grants DA-031988 and DA-03672. NIH/NIDA did not play any role in data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atwood BK, Huffman J, Straiker A, Mackie K. JWH018, a common constituent of ‘Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB receptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:585–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood BK, Lee D, Straiker A, Widlanski TS, Mackie K. CP47,497-C8 and JWH073, commonly found in ‘Spice’ herbal blends, are potent and efficacious CB(1) cannabinoid receptor agonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;659:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung MM, Griffin G, Huffman JW, Wu M, Keel C, Yang B, Showalter VM, Abood ME, Martin BR. Influence of the N-1 alkyl chain length of cannabimimetic indoles upon CB(1) and CB(2) receptor binding. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:133–40. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Prescott WR. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol discrimination in rats as a model for cannabis intoxication. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Griffin G, Di Marzo V, Martin BR. Evidence for a new G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor in mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Zimmerman SM, Saffell AR, Prather PL, Fantegrossi WE. Differential drug-drug interactions of the synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073: Implications for drug abuse liability and pain therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:350–61. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.206003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Gallus-Zawada A, Radominska-Pandya A, Vasiljevik T, Prisinzano TE, Fantegrossi WE, Moran JH, Prather PL. Monohydroxylated metabolites of the K2 synthetic cannabinoid JWH-073 retain intermediate to high cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R) affinity and exhibit neutral antagonist to partial agonist activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:952–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DR, Gold LH, Ward SJ, Balster RL, Martin BR. Aminoalkylindole analogs: cannabimimetic activity of a class of compounds structurally distinct from delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:1118–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Slangen JL. Effects of training dose on discrimination and cross-generalization of chlordiazepoxide, pentobarbital and ethanol in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;88:341–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00180836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresen S, Ferreiros N, Putz M, Westphal F, Zimmermann R, Auwarter V. Monitoring of herbal mixtures potentially containing synthetic cannabinoids as psychoactive compounds. J Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:1186–94. doi: 10.1002/jms.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Schulze DR, Hruba L, McMahon LR. JWH-018 and JWH-073: Delta-tetrahydrocannabinol-like discriminative stimulus effects in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:37–45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.187757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Balster RL, Barrett RL, Britt DT, Martin BR. A comparison of the discriminative stimulus properties of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and CP 55,940 in rats and rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:479–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Ledent C, Freund TF. Novel cannabinoid-sensitive receptor mediates inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001;106:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW. Cannabimimetic indoles, pyrroles and indenes. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:705–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW. The search for selective ligands for the CB2 receptor. Curr Pharm Des. 2000;6:1323–37. doi: 10.2174/1381612003399347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW, Padgett LW. Recent developments in the medicinal chemistry of cannabimimetic indoles, pyrroles and indenes. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1395–411. doi: 10.2174/0929867054020864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW, Dai D, Martin BR, Compton DR. Design, synthesis and pharmacology of cannabimimetic indoles. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1994;4:563–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW, Zengin G, Wu MJ, Lu J, Hynd G, Bushell K, Thompson AL, Bushell S, Tartal C, Hurst DP, Reggio PH, Selley DE, Cassidy MP, Wiley JL, Martin BR. Structure-activity relationships for 1-alkyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indoles at the cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptors: steric and electronic effects of naphthoyl substituents. New highly selective CB(2) receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:89–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TU, Lamb RJ, Makriyannis A, Lin S, Goutopoulos A. Delta-9-THC training dose as a determinant for (R)-methanandamide generalization in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;140:519–522. doi: 10.1007/s002130050797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe T, Lamb R, Lin S, Makriyannis A. Delta9-THC training dose as a determinant for (R)-methanandamide generalization in rats: a systematic replication. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:81–86. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TU, Li C, Vadivel SK, Makriyannis A. Discriminative stimulus functions of methanandamide and delta(9)-THC in rats: tests with aminoalkylindoles (WIN55,212-2 and AM678) and ethanol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1708-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TU, Deng H, Vadivel SK, Makriyannis A. Cannabinergic aminoalkylindoles, including AM678=JWH018 found in ‘Spice’, examined using drug (Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol) discrimination for rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:498–507. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328349fbd5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TU, LeMay BJ, Halikhedkar A, Wood JA, Vadivel SK, Zvonok A, Makriyannis A. Differentiation between low- and high-efficacy CB1 receptor agonists using a drug discrimination protocol for rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3257-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manera C, Tuccinardi T, Martinelli A. Indoles and related compounds as cannabinoid ligands. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:370–87. doi: 10.2174/138955708783955935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Balster RL. Pharmacological specificity of the phencyclidine discriminative stimulus in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;9:971–975. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Lefever TW, Novak SP, Blough BE, Wiley JL. RTI Press publication No OP-0014-1307. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press; 2013. Prediction and prevention of prescription drug abuse: Role of preclinical assessment of substance abuse liability. Retrieved from http://www.rti.org/rtipress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perio A, Rinaldi-Carmona M, Maruani J, Barth F, Le Fur G, Soubrie P. Central mediation of the cannabinoid cue: Activity of a selective CB1 antagonist, SR 141716A. Behav Pharmacol. 1996;7:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely KA, Brents LK, Radominska-Pandya A, Endres GW, Keyes GS, Moran JH, Prather PL. A major glucuronidated metabolite of JWH-018 is a neutral antagonist at CB1 receptors. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:825–7. doi: 10.1021/tx3000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter VM, Compton DR, Martin BR, Abood ME. Evaluation of binding in a transfected cell line expressing a peripheral cannabinoid receptor (CB2): identification of cannabinoid receptor subtype selective ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:989–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song ZH, Bonner TI. A lysine residue of the cannabinoid receptor is critical for receptor recognition by several agonists but not WIN55212-2. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:891–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Goldberg SR. Cannabinoids: reward, dependence, and underlying neurochemical mechanisms--a review of recent preclinical data. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:115–34. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi B, Lee JD. Internet highs--seizures after consumption of synthetic cannabinoids purchased online. J Addict Med. 2012;6:240–1. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182619004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U S Drug Enforcement Administration OoDC. National Forensic Laboratory Information System: Midyear report 2012. Springfield, VA: U S Drug Enforcement Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama N, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y. URB-754: A new class of designer drug and 12 synthetic cannabinoids detected in illegal products. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;227:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vann RE, Warner JA, Bushell K, Huffman JW, Martin BR, Wiley JL. Discriminative stimulus properties of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in C57Bl/6J mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;615:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardakou I, Pistos C, Spiliopoulou C. Spice drugs as a new trend: mode of action, identification and legislation. Toxicol Lett. 2010;197:157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebelhaus JM, Poklis JL, Poklis A, Vann RE, Lichtman AH, Wise LE. Inhalation exposure to smoke from synthetic “marijuana” produces potent cannabimimetic effects in mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL. Cannabis: discrimination of “internal bliss”? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:257–60. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Huffman JW, Balster RL, Martin BR. Pharmacological specificity of the discriminative stimulus effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995a;40:81–6. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Martin BR, Huffman JW. 1-Pentyl-3-phenylacetylindoles and JWH-018 share in vivo cannabinoid profiles in mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Barrett RL, Lowe J, Balster RL, Martin BR. Discriminative stimulus effects of CP 55,940 and structurally dissimilar cannabinoids in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1995b;34:669–76. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Huffman JW, Balster RL, Thomas BF. RTI Press publication No OP-0007-1111. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press; 2011. Hijacking of basic research: The case of synthetic cannabinoids. Retrieved from http://www.rti.org/rtipress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Lefever TW, Grabenauer M, Moore KN, Thomas BF. Cannabinoids in disguise: Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-like effects of tetramethylcyclopropyl ketone indoles. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75:145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Compton DR, Dai D, Lainton JA, Phillips M, Huffman JW, Martin BR. Structure-activity relationships of indole- and pyrrole-derived cannabinoids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:995–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Barratt MJ. Synthetic cannabis: A comparison of patterns of use and effect profile with natural cannabis in a large global sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Masaki MA, Geula C. Discriminative stimulus effects of morphine: effects of training dose on agonist and antagonist effects of mu opioids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]